Seronegative Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxia in Children: Autoimmune Encephalitis Spectrum Disorder or a Distinct Entity?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Case Report

4. Isolated Seronegative IMCA in Children: An Underdiagnosed Clinical Entity

5. Classifying Isolated Seronegative IMCA: A Variant of Pediatric AIE Spectrum or a Distinct Neurological Entity?

6. The Role of Disease Biomarkers

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garone, G.; Reale, A.; Vanacore, N.; Parisi, P.; Bondone, C.; Suppiej, A.; Brisca, G.; Calistri, L.; Cordelli, D.M.; Savasta, S.; et al. Acute ataxia in paediatric emergency departments: A multicentre Italian study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2019, 104, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellucci, T.; Van Mater, H.; Graus, F.; Muscal, E.; Gallentine, W.; Klein-Gitelman, M.S.; Benseler, S.M.; Frankovich, J.; Gorman, M.P.; Van Haren, K.; et al. Clinical approach to the diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis in the pediatric patient. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 7, e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quack, L.; Glatter, S.; Wegener-Panzer, A.; Cleaveland, R.; Bertolini, A.; Endmayr, V.; Seidl, R.; Breu, M.; Wendel, E.; Schimmel, M.; et al. Autoantibody status, neuroradiological and clinical findings in children with acute cerebellitis. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2023, 47, 118–130, Erratum in Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2024, 51, 151–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2024.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; Du Montcel, S.T.; Baliko, L.; Berciano, J.; Boesch, S.; Depondt, C.; Giunti, P.; Globas, C.; Infante, J.; Kang, J.-S.; et al. Scale for the assessment and rating of ataxia: Development of a new clinical scale. Neurology 2006, 66, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Pan, G.; Zhou, S.; Shen, J.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, L. Etiologies and clinical characteristics of acute ataxia in a single national children’s medical center. Brain Dev. 2024, 46, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graus, F.; Titulaer, M.J.; Balu, R.; Benseler, S.; Bien, C.G.; Cellucci, T.; Cortese, I.; Dale, R.C.; Gelfand, J.M.; Geschwind, M.; et al. A clinical approach to diagnosis of autoimmune encephalitis. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekunov, J.; Blacker, C.J.; Vande Voort, J.L.; Tillema, J.M.; Croarkin, P.E.; Romanowicz, M. Immune mediated pediatric encephalitis- need for comprehensive evaluation and consensus guidelines. BMC Neurol. 2020, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.D.; Lee, J.S.; Kang, H.C.; Kim, S.H. Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes of Seronegative Pediatric Autoimmune Encephalitis. J. Clin. Neurol. 2021, 17, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, R.C.; Gorman, M.P.; Lim, M. Autoimmune encephalitis in children: Clinical phenomenology, therapeutics, and emerging challenges. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2017, 30, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitoma, H.; Manto, M.; Hadjivassiliou, M. Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxias: Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment Based on Immunological and Physiological Mechanisms. J. Mov. Disord. 2021, 14, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Graus, F.; Honnorat, J.; Jarius, S.; Titulaer, M.; Manto, M.; Hoggard, N.; Sarrigiannis, P.; Mitoma, H. Diagnostic Criteria for Primary Autoimmune Cerebellar Ataxia-Guidelines from an International Task Force on Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxias. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Grunewald, R.A.; Shanmugarajah, P.D.; Sarrigiannis, P.G.; Zis, P.; Skarlatou, V.; Hoggard, N. Treatment of Primary Autoimmune Cerebellar Ataxia with Mycophenolate. Cerebellum 2020, 19, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCracken, L.; Zhang, J.; Greene, M.; Crivaro, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Kamoun, M.; Lancaster, E. Improving the antibody-based evaluation of autoimmune encephalitis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 4, e404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Wild, G.; Shanmugarajah, P.; Grünewald, R.A.; Akil, M. Indirect immunofluorescent assay as an aid in the diagnosis of suspected immune mediated ataxias. Cerebellum Ataxias 2021, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahn, C.; Budhram, A.; Alikhani, K.; AlOhaly, N.; Beecher, G.; Blevins, G.; Brooks, J.; Carruthers, R.; Comtois, J.; Cowan, J.; et al. Canadian Consensus Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Autoimmune Encephalitis in Adults. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 51, 734–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosadini, M.; Thomas, T.; Eyre, M.; Anlar, B.; Armangue, T.; Benseler, S.M.; Cellucci, T.; Deiva, K.; Gallentine, W.; Gombolay, G.; et al. International Consensus Recommendations for the Treatment of Pediatric NMDAR Antibody Encephalitis. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 8, e1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaetani, L.; Blennow, K.; Calabresi, P.; Di Filippo, M.; Parnetti, L.; Zetterberg, H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2019, 90, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammeyer, R.; Mizenko, C.; Sillau, S.; Richie, A.; Owens, G.; Nair, K.V.; Alvarez, E.; Vollmer, T.L.; Bennett, J.L.; Piquet, A.L. Evaluation of Plasma Neurofilament Light Chain Levels as a Biomarker of Neuronal Injury in the Active and Chronic Phases of Autoimmune Neurologic Disorders. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 689975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yang, J.; Hou, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, K. Prediction of clinical progression in nervous system diseases: Plasma glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). Eur. J. Med. Res. 2024, 29, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotto, S.; Gajofatto, A.; Zuliani, L.; Zoccarato, M.; Gastaldi, M.; Franciotta, D.; Cantalupo, G.; Piardi, F.; Polo, A.; Alberti, D.; et al. Serum and CSF neurofilament light chain levels in antibody-mediated encephalitis. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 1643–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, R.; Krýsl, D.; Bergquist, F.; Andrén, K.; Malmeström, C.; Asztély, F.; Axelsson, M.; Menachem, E.B.; Blennow, K.; Rosengren, L.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers of neuronal and glial cell damage to monitor disease activity and predict long-term outcome in patients with autoimmune encephalitis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2016, 23, 796–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, J.; Mariotto, S.; Bastiaansen, A.E.; Paunovic, M.; Ferrari, S.; Alberti, D.; de Bruijn, M.A.; Crijnen, Y.S.; Schreurs, M.W.; Neuteboom, R.F.; et al. Predictive Value of Serum Neurofilament Light Chain Levels in Anti-NMDA Receptor Encephalitis. Neurology 2023, 100, e2204–e2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giovannoni, F.; Quintana, F.J. The Role of Astrocytes in CNS Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, N.S.N.; Zimmerman, K.A.; Moro, F.; Heslegrave, A.; Maillard, S.A.; Bernini, A.; Miroz, J.-P.; Donat, C.K.; Lopez, M.Y.; Bourke, N.; et al. Axonal marker neurofilament light predicts long-term outcomes and progressive neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabg9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Laboratory Test Time | CSF Analysis | OCBs | MOG/ AQP-4 Abs (Serum) | Abs Against Cell-Surface and Intracellular Antigens * | GFAP (Serum) pg/mL | NFL (Serum) pg/mL | WGS | Tissue-Based Immunohistochemistry | MRI Scan | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | WBC 30/μL, Protein 18 mg/dL, Glucose 50 mg/dL | Weak type 2 | negative | negative | Brain: normal Cervical spine: normal | Systemic autoimmune panel: negative EEG: normal | ||||

| 3 months | WBC 0/μL, Glucose 60 mg/dL, Protein 57 mg/dL | Type 4 | negative | negative | ||||||

| 6 months | 325.0 | 9.5 | VUS in SLC1A3–AD, mother homozygous ** | Brain: normal Cervical spine: normal | ||||||

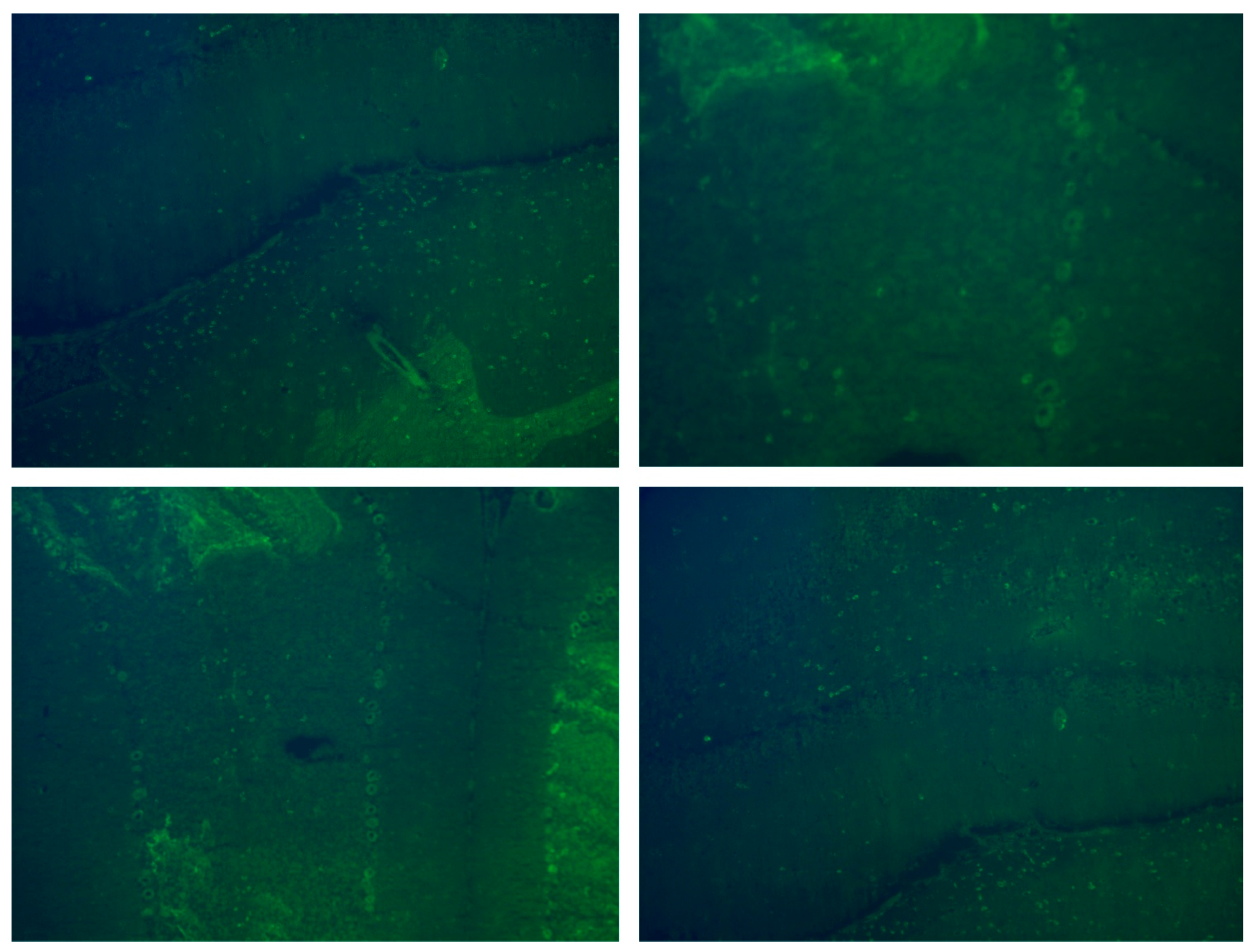

| 12 months | Type 1 | negative | 377 | 14.3 | Hippocampus: negative Cerebellum: positive signal of Purkinje cells | Urine neuroblastoma and tumor blood markers: negative | ||||

| 18 months | 222 | 9.2 | Whole body: normal | |||||||

| 21 months | 113 | 12.5 |

| Age (Years) | Sex | Abs Status | Clinical Presentation | MRI Cerebellar Lesions | Additional MRI Lesions | CSF Findings | mRS (Onset) | mRS (Last f/u) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.2 | m | negative | ataxia, dysmetria, upper respiratory tract infection | unilat. lesions, vasogenic edema, gd (+) | none | pleocytosis, OCB (+) | 4 | 2 |

| 9.2 | m | negative | ataxia, dysmetria, headache, nausea, vomiting, fever | unilat. cortical lesion + vasogenic edema/swelling | none | pleocytosis, intrathecal IgG + IgM synthesis, OCB (+), enterovirus (PCR) * | 3 | 1 |

| 17.6 | m | negative | ataxia | bil. lesions, vasogenic edema/swelling | none | pleocytosis | 2 | 2 |

| 2.1 | m | negative | ataxia, dysmetria, dysarthria, respiratory tract infection, fever | bil. white matter/cortical lesions | none | pleocytosis, OCB (+), IgM M. pneumoniae abs | 4 | 1 |

| 7.4 | m | negative | ataxia, headache, vomiting | bil. lesions, vasogenic edema/swelling, cerebellar herniation | white matter, cortical/subcortical | pleocytosis | 2 | 0 |

| 2.5 | m | negative | ataxia, nausea, upper respiratory tract infection | none | none | pleocytosis | 4 | 3 |

| 5.1 | f | negative | ataxia, dysmetria, tremor, dysarthria, headache | none | none | pleocytosis, OCB (+) | 4 | 3 |

| 6.3 | f | negative | ataxia, vomiting, headache | unilat. lesions, vasogenic edema | none | none | 3 | 1 |

| 2.5 | f | negative | ataxia, tremor | none | none | pleocytosis, OCB (+) | 3 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maria, G.; Chrysanthi, T.; Eudokia, S.; Theofanis, P.; Nikolaos, K.; Constantinos, K.; John, T.; Dionysia, G. Seronegative Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxia in Children: Autoimmune Encephalitis Spectrum Disorder or a Distinct Entity? Children 2025, 12, 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111513

Maria G, Chrysanthi T, Eudokia S, Theofanis P, Nikolaos K, Constantinos K, John T, Dionysia G. Seronegative Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxia in Children: Autoimmune Encephalitis Spectrum Disorder or a Distinct Entity? Children. 2025; 12(11):1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111513

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaria, Gontika, Tsimakidi Chrysanthi, Salamou Eudokia, Prattos Theofanis, Kallias Nikolaos, Kilidireas Constantinos, Tzartos John, and Gkougka Dionysia. 2025. "Seronegative Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxia in Children: Autoimmune Encephalitis Spectrum Disorder or a Distinct Entity?" Children 12, no. 11: 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111513

APA StyleMaria, G., Chrysanthi, T., Eudokia, S., Theofanis, P., Nikolaos, K., Constantinos, K., John, T., & Dionysia, G. (2025). Seronegative Immune-Mediated Cerebellar Ataxia in Children: Autoimmune Encephalitis Spectrum Disorder or a Distinct Entity? Children, 12(11), 1513. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111513