Addressing Social Determinants of Health Service Gaps in Chinese American Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Highlights

- Caregiver and provider perspectives are both needed to understand how patients navigate addressing social determinants of health for their children and families.

- Patient cultural values and beliefs are integral to understanding how they contribute to patient behaviors and when designing interventions to address social determinants of health.

- Adaptations in health services settings need to consider cultural diversity and language concordance among Chinese American immigrant populations based on their region of origin.

- Structural limitations in health services workflow (e.g., reduced staff, digital tools not in the patient’s primary language) may inhibit caregivers’ ability to address social determinants of health needs efficiently.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Objectives

1.2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.1.1. Interview Sample

2.1.2. Data Analysis

- Familiarization with the data: All transcripts were read multiple times in their original language to ensure accuracy and depth of understanding.

- Generating initial codes: A preliminary codebook was developed based on the interview guide, the interviewer’s notes, and emergent issues raised by participants as identified during repeated readings.

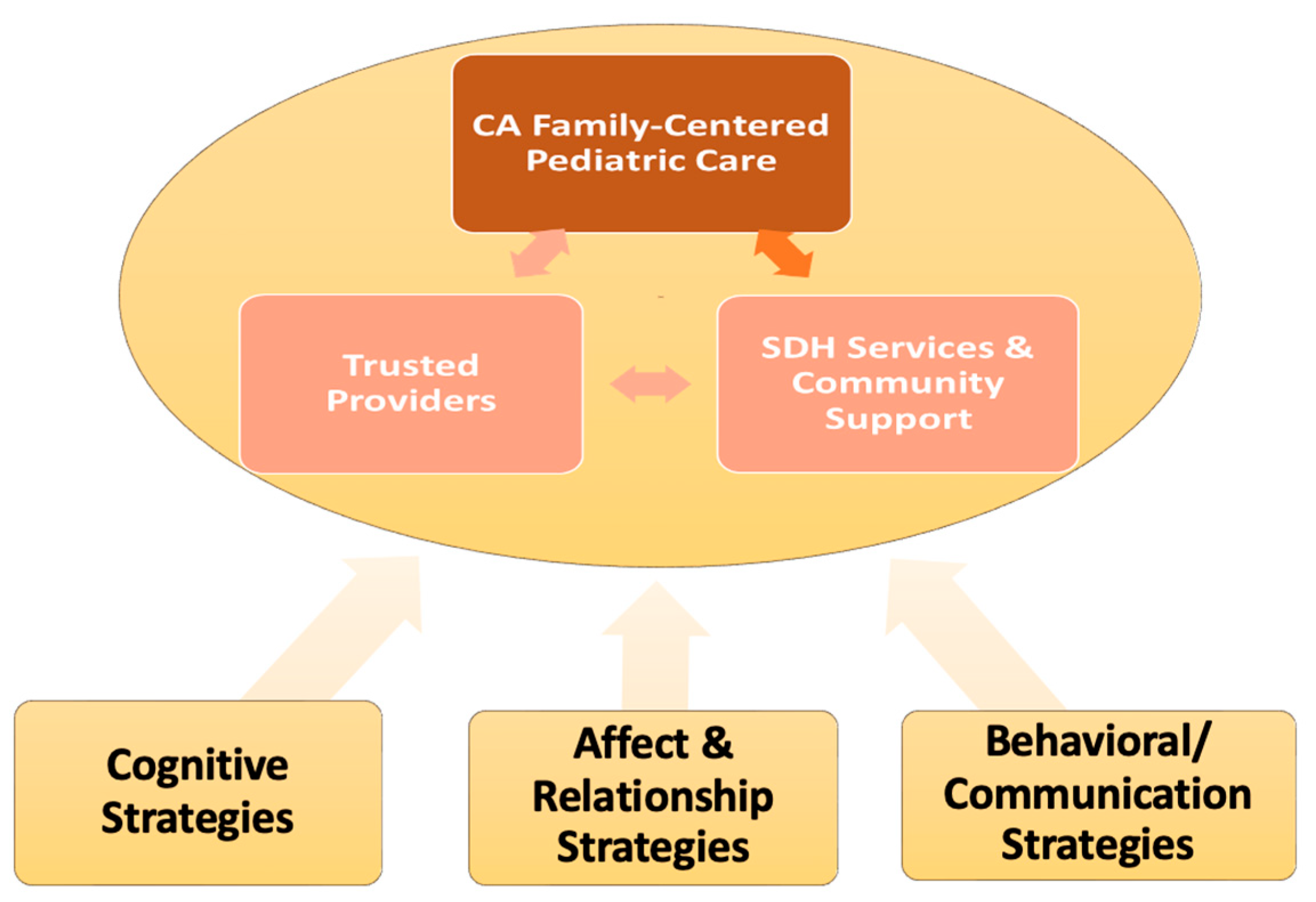

- Searching for themes: Codes were clustered into broader categories reflecting cognitive, affective/relational, and behavioral/communication patterns, as well as contextual system-level factors.

- Reviewing themes: Candidate themes were refined, checked against the dataset for internal consistency, and revised through team discussion.

- Defining and naming themes: Final themes were clearly labeled to capture the essence of caregiver and provider experiences within the PEC domains and across system-level determinants.

- Configuring final analysis components: To integrate perspectives systematically, final themes were organized into six components: Cognitive factors (knowledge, awareness, and provider understanding of cultural context). Affective/relational factors (trust, empathy, stigma, and interpersonal dynamics). Behavioral/communication factors (disclosure of needs, culturally concordant communication, and patient engagement). Contextual/structural factors (health system processes, staffing, intake workflows, and referral mechanisms). Broader systemic forces (economic instability, immigration stress, racism, and policy-level barriers affecting families).

2.1.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

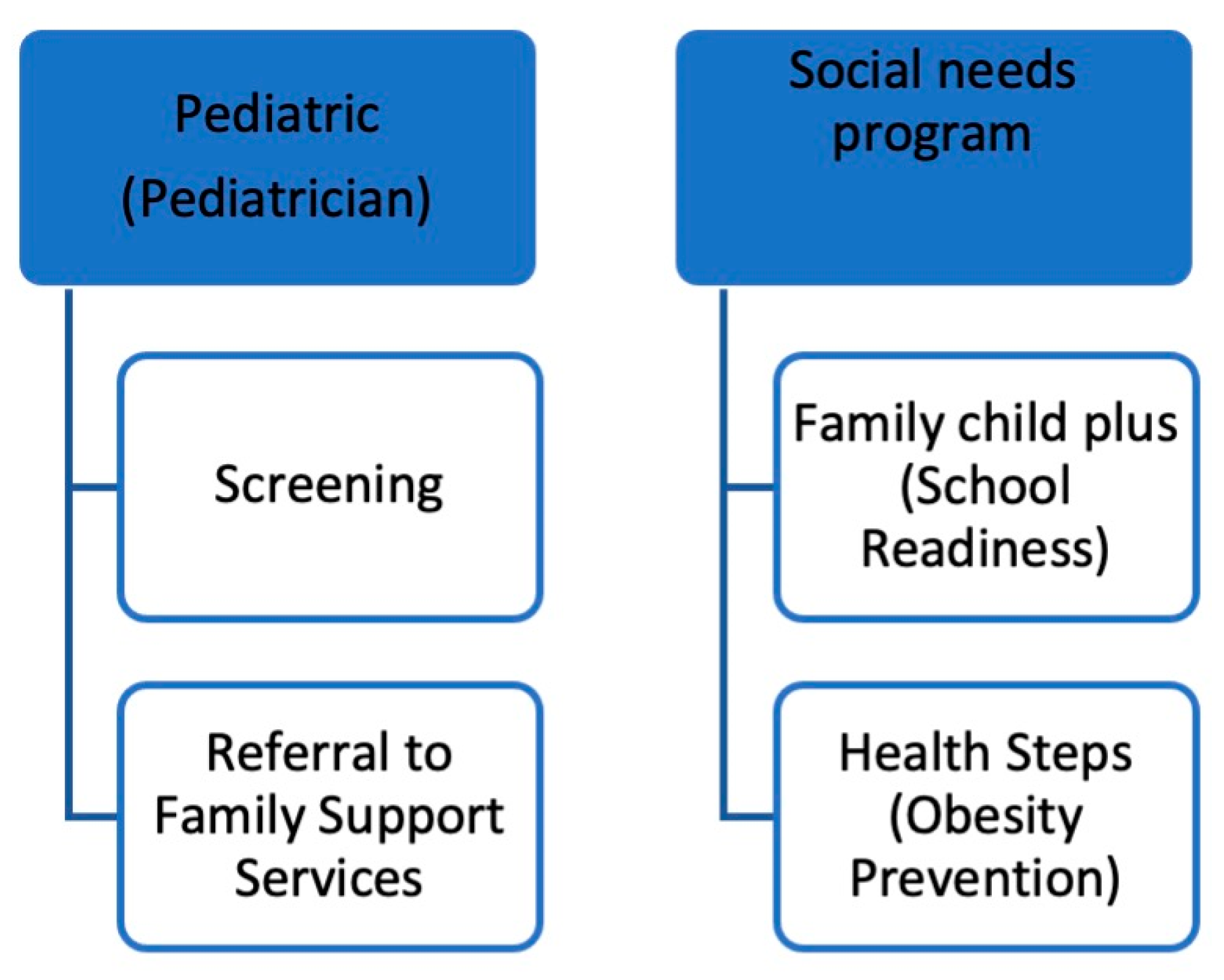

3.1. SDOH Services Processes from Provider Perspective

- •

- Short Staff and reduced family support staff/social workers post COVID-19 affected continuity of care to ensure SDOH needs were met, as well as relationship building among patients and providers. Also, the waitlist for social services may be up to two months. For instance, the provider quoted below stated,

“Uh, for example we only know that we refer families with that families information and provide it with um the- shared all of the information with the family support service team, but we don’t know the status of um each case has been closed or not. Um the only way we were able to know is that we ask family, “Did you get support?” Normally family, if family don’t contact you, um they got support um quite probably within 24 h or something, but we get that feedback from family not from the staff member.”Quotes from the SNS team member

“I think it would be helpful to have somebody from Healthy Steps here every day. We used to have someone here every day before COVID, and then of course COVID happened so. Because they’re the ones with all the resources and all the information for the programs, as far as the MAs, what we do is give the patient the form, have them fill it out, go in with the provider, they discuss with the provider, they discuss with the provider, then when they come out they’ll get the referral and the things that they need, but to actually have someone from the program...umm you know..hands on..someone who really needs it in the moment, you know..because we wouldn’t want anybody to fall out the loop….you know things happen in the process of things..not saying that it has happened, but if it’s something to be prevented to have someone there everyday to help the patient with these matters.”Quote from the medical assistant

“I would say..umm. that relationship..umm.. trust the parents have with visitors allows for them to feel comfortable in sharing umm..or seeking support for the challenges they are experiencing. Wheras if it’s someone they don’t know, it would be a little bit challenging for them to share.. when they feel they can trust the person, they open up more.”Quote from the Healthy Steps provider

- Due to the immigration status, negative consequences, or not to bring “shame” on the family and disclose family struggles, caregivers did not complete the SDOH screeners completely. Patients ask for help within the family first. Additionally, fear of disclosing needs due to the immigration status may also be linked with cultural stigma or government mistrust. External trusted community partners outside the healthcare system may be engaged to assist patients with addressing an SDOH need. For instance, providers stated:

“Um, so that’s one of the feedback that I got from the clinic staff, and um, and so yeah and that, that idea that sometimes there’s underreporting of needs and also our population, um our families are immigrant families, most of them, and there may also be some fear of reporting social needs and um because of their immigration status, but in general we haven’t had people refusing to fill it out or saying, “Why are you asking these questions?” So, people understand why we’re doing it.”.Quote from the SNS team member

“So we do pair the families up with um someone who speaks the language and is also a cultural match. Um, but I’ve, I’ve never, like they’ve never, um, I think oftentimes what we hear is um from the Chinese speaking families is that they don’t need help right there. They don’t like to ask for help. So I guess, you know, in, in thinking about this, reflecting on it, um I think we have to find a better way to get them to feel comfortable to ask for help because there might be some needs, but they just don’t- like I think, I’m not sure if I’m wrong about this, but I feel that in the Chinese culture they, they don’t like to ask for help.”Quote from Healthy Steps team member

- Patient intake forms in written paper form in English were a limitation, given the time constraints of translation, which would take up time from the provider visit to provide care.

“And then there’s a number that if you want to schedule a food pantry um they can call that number or if we check um that item for her, for that, for for for the participants, someone will also reach out to them to schedule a food pantry. Um, that they can grab the food, but um we don’t have very specific um program really geared towards scouting someone to uh support families filling different kind of forms in English and get finance support.”

3.2. SDOH Services Processes from the Caregiver Perspective

“My husband went out shopping once a week to buy all the things family needed. Prices were very high at that time. You could buy many things for over $100 before the pandemic, but at that time, it cost us almost $300 to $400 a week. Many things were in short supply, and prices were high.”

“My kids love to play with things that produce sound, such as banging on buckets and knocking on the floor. At that time, the downstairs complained about us, saying the kids were too noisy. Because of that and the fact that the rent was too high, we moved to…”

“I was actually okay. I guess it’s because of the pandemic, and I’ve been staying home for long. My mood will probably be better if I could go out somewhere to have a break. But at present, whenever I think about going out, my worries start to bother me. My cousins asked me if I was interested in joining them at the water park in the summer. But I didn’t dare to enter. Worries obsessed me at the very first moment when I thought about it. Things like clutters of people gathering, no face masks, and many more came to my mind.”

“My boy is well-behaved, and he wears masks properly. Some small children don’t want to wear masks. Maybe because my child has been staying at home for too long, he knows that once he wears a mask, he is going out to play. Therefore, he wears the mask well. We also disinfect in time after coming home. The situation is okay.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Cognitive Strategies

4.2. Affect and Relationship Strategies

4.3. Behavioral/Communications Strategies

5. Conclusions

Significance and Implications of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDOH | Social determinants of health |

| CA | Chinese Americans |

| PEC | Partnership, Engagement, and Collaboration |

| FHC | Family Health Centers |

| FSS | Family Support Services |

| SNS | Social Need Service |

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030. Available online: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Health Care’s Blind Side: The Overlooked Connection Between Social Needs and Good Health; Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dzau, V.J.; McClellan, M.B.; McGinnis, J.M.; Finkelman, E.M. (Eds.) Vital Directions for Health & Health Care: An Initiative of the National Academy of Medicine; National Academy of Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Annual Wellness Visit: Social Determinants of Health Risk Assessment; Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Castrucci, B.C.; Auerbach, J. Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing social determinants of health. Health Aff. Forefr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.; Fracci, S.; Wojtowicz, J.; McCune, E.; Sullivan, K.; Sigman, G.; O’Keefe, J.; Qureshi, N.K. Ethnicity, social determinants of health, and pediatric primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2022, 13, 21501319221112248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakefield, W.S.; Olusanya, O.A.; White, B.; Shaban-Nejad, A. Social determinants and indicators of COVID-19 among marginalized communities: A scientific review and call to action for pandemic response and recovery. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2022, 17, e193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, J.; Yang, A.; Anuforo, B.; Chou, J.; Brogden, R.; Xu, B.; Cantor, J.C.; Wang, S. Health related social needs among Chinese American primary care patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: Implications for cancer screening and primary care. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 674035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, A.; Yi, S.S.; Ethoan, L.N.; Tsoh, J.Y.; Yellow Horse, A.J.; Kwon, S.C.; Samoa, R.; Aitaoto, N.; Takeuchi, D.T. Improving Asian American health during the syndemic of COVID-19 and racism. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 45, 101313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, J.Y.; Liu, M.F. Culturally tailored interventions for ethnic minorities: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2078–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.Y.; Kwon, S.C.; Cheng, S.; Kamboukos, D.; Shelley, D.; Brotman, L.M.; Kaplan, S.A.; Olugbenga, O.; Hoagwood, K. Unpacking partnership, engagement, and collaboration research to inform implementation strategies development: Theoretical frameworks and emerging methodologies. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.V.; Chuang, R.J.; Rushing, M.; Naylor, B.; Ranjit, N.; Pomeroy, M.; Markham, C. Social determinants of health-related needs during COVID-19 among low-income households with children. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, R.L.; Bui, L.; Shen, Z.; Pressman, A.; Moreno, M.; Brown, S.; Nilon, A.; Miller-Rosales, C.; Azar, K.M.J. Evaluation of a social determinants of health screening questionnaire and workflow pilot within an adult ambulatory clinic. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.T.; Ea, E.; Kalbag, A.; Lopez, L.L.; Li, R.; Setoguchi, S.; Wu, B.; Gaur, S. Addressing Gaps in Health Care Delivery Among Asian Americans Through Community-Driven Policy Action. Am. J. Public Health 2025, 115, S134–S137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavilon, J.; Virgin, V. Social Determinants of Immigrants’ Health in New York City: A Study of Six Neighborhoods in Brooklyn and Queens; Center for Migration Studies of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Metcalf, S.S.; Palmer, H.D.; Northridge, M.E. Spatial analysis of Chinese American ethnic enclaves and community health indicators in New York City. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 815169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Kandula, N.R.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Morey, B.N.; Patel, S.A.; Wong, S.; Yang, E.; Yi, S. Social determinants of cardiovascular health in Asian Americans: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e296–e315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.Y.; Islam, R.B.; Gandrakota, N.; Shah, M.K. The social determinants of health associated with cardiometabolic diseases among Asian American subgroups: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, H.; Shi, Y.; Sevick, M.; Li, H.; Beasley, J.M.; Yi, S.; Friedman, O.Z.; Hu, L. Social Determinants of Health Barriers in Chinese Americans at Risk for Type 2 Diabetes. In Proceedings of the Context Matters: Bridging Perspectives in Behavioral Medicine, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 March 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C.M.; Strader, L.C.; Pratt, J.G.; Maiese, D.; Hendershot, T.; Kwok, R.K.; Hammond, J.A.; Huggins, W.; Jackman, D.; Pan, H.; et al. The PhenX Toolkit: Get the most from your measures. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011, 174, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keum, B.T.; Miller, M.J.; Lee, M.; Chen, G.A. Color-Blind Racial Attitudes Scale for Asian Americans: Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance across generational status. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2018, 9, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.T.H.; Li, L.C.; Kim, B.S.K. The Asian American Racism-Related Stress Inventory: Development, factor analysis, reliability, and validity. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, A. English-Speaking Asian Americans Stand Out for Their Technology Use. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2016/02/18/English-speaking-Asian-Americans-stand-out-for-their-technology-use (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Ortega, P.; Shin, T.M.; Martinez, G.A. Rethinking the term “limited English proficiency” to improve language-appropriate healthcare for all. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2022, 24, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, L.; Adetayo, O.A. Cultural competence and ethnic diversity in healthcare. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzl, J.M.; Hansen, H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J.; Chapman, M.V.; Lee, K.M.; Merino, Y.M.; Thomas, T.W.; Payne, B.K.; Eng, E.; Day, S.H.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e60–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.Y.; Handorf, E.A.; Rao, A.D.; Siu, P.T.; Tseng, M. Acculturative stress and depressive symptoms among Chinese Immigrants: The role of gender and social support. J. Racial Ethn. Heal. Disparities 2021, 8, 1130–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cheah, C.S.L.; Zong, X.; Ren, H. Parental stress and Chinese American preschoolers’ adjustment: The nediating role of parenting. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, R.; Patel, S.; Choy, C.; Taher, M.; Garcia-Dia, M.J.; Singh, H.; Kim, S.; Mohaimin, S.; Dhar, R.; Naeem, A.; et al. Influence of organizational and social contexts on the implementation of culturally adapted hypertension control programs in Asian American-serving grocery stores, restaurants, and faith-based community sites: A qualitative study. Trans. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 1525–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Islam, N.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Wu, B.; Feldman, N.; Tamura, K.; Jiang, N.; Lim, S.; Wang, C.; Bubu, O.M.; et al. A social media-based diabetes intervention for low-income Mandarin-speaking Chinese immigrants in the United States: Feasibility study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e37737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.; Zhang, L.; Park, J.S.; Tan, Y.L.; Kwon, S.C. The importance of community and culture for the recruitment, engagement, and retention of Chinese American immigrants in health interventions. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021, 11, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, N.; Grant, A.; Bubu, O.; Chung, A.; Wallace, D. 0791 Perceived racial discrimination predicts poor PAP adherence: A pilot study. Sleep 2022, 45, A343–A344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FHC service context (Pediatric setting) | Provider Care Team in Pediatric Setting: Screening + (social needs programs include: Healthy Steps (an obesity prevention program), ParentChild + (a home visiting program to support child developmental milestones), and Family Support Services (FSS) connect to community resources to address needs (e.g., childcare, transportation, food/financial security, ESL classes). |

| Interview sample | n = 2 Pediatrician + 6 SNS staff |

| Sample interview questions |

|

| Select thematic responses | Q1 Patient Screening process included:

|

| Interview Sample | 6 Chinese American Caregivers |

|---|---|

| Sample Patient Questions | Where do you go for your first point of contact for these needs (e.g., food, housing, childcare, financial assistance)? Is there a trusted person in your community that you might reach out to first? |

| Select Thematic Responses |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chung, A.; Chong, S.; Chung, D.; Gee, A.; Stanton-Koko, M.; Huang, K.-Y. Addressing Social Determinants of Health Service Gaps in Chinese American Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2025, 12, 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111499

Chung A, Chong S, Chung D, Gee A, Stanton-Koko M, Huang K-Y. Addressing Social Determinants of Health Service Gaps in Chinese American Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children. 2025; 12(11):1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111499

Chicago/Turabian StyleChung, Alicia, Stella Chong, Debbie Chung, Amira Gee, Monica Stanton-Koko, and Keng-Yen Huang. 2025. "Addressing Social Determinants of Health Service Gaps in Chinese American Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Children 12, no. 11: 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111499

APA StyleChung, A., Chong, S., Chung, D., Gee, A., Stanton-Koko, M., & Huang, K.-Y. (2025). Addressing Social Determinants of Health Service Gaps in Chinese American Caregivers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children, 12(11), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111499