Screen Time and Sleep Bruxism—A Comparison Between the Present Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

Highlights

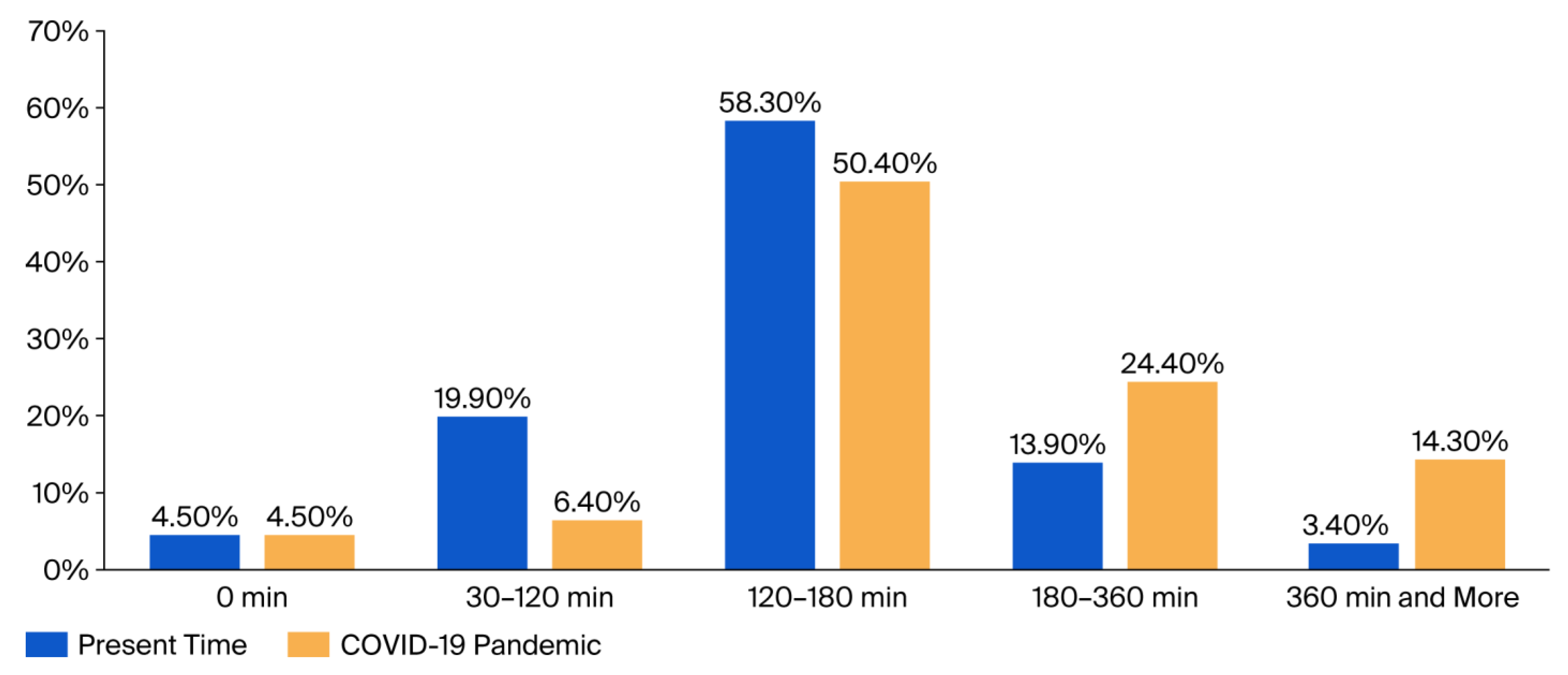

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, children’s daily screen time increased, with a marked rise observed in those using screens for more than 3 h per day.

- Children with sleep bruxism spent longer periods on screens than children without bruxism (with an average difference of 32 min).

- Extended screen time may contribute to the development or worsening of sleep bruxism in children.

- Parents and clinicians should encourage balanced screen use and healthy sleep routines to reduce bruxism risk.

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. History and Definition of Bruxism

1.2. Epidemiology in Children

1.3. Etiology and Risk Factors

1.4. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Screen Time on Bruxism

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

- -

- Preschool age—3–6 years;

- -

- Primary school age—7–10 years;

- -

- Lower secondary school age—11–14 years.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Children aged 3 to 14 years whose parents properly completed the informed consent form provided;

- -

- Children with bruxism were identified based on parental reports of teeth grinding at night, corresponding to possible bruxism [2].

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Children with systemic or neurological disorders that affect sleep or muscle activity (e.g., epilepsy, cerebral palsy, or parkinsonian syndromes);

- -

- Children currently undergoing pharmacological treatment that could influence bruxism or sleep patterns;

- -

- Children with severe craniofacial anomalies or syndromes;

- -

- Children whose parents did not complete the questionnaire adequately or declined consent.

2.2. Data Collection

Questionnaire Method

- -

- Child and parent demographics;

- -

- General health status and illnesses of the child;

- -

- Dietary habits and physical activity;

- -

- Sleep and awake bruxism;

- -

- Sleep-related habits;

- -

- Oral symptoms and harmful habits;

- -

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the child’s daily life;

- -

- Screen time.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

- -

- Descriptive statistics—mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables.

- -

- Chi-square (χ2) test—to evaluate associations between categorical variables, such as screen time categories and sleep bruxism status.

- -

- One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s HSD—to compare mean screen time across age groups and identify significant pairwise differences.

- -

- t-test—to compare mean daily screen time between two groups of children.

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AASM | American Academy of Sleep Medicine |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| RMMA | Rhythmic masticatory muscle activity |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| TMD | Temporomandibular Disorders |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| Tukey’s HSD | Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference |

References

- Marie, M.M.; Pietkiewicz, M. La bruxomanie [Bruxism]. Rev. Stomatol. 1907, 14, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Koyano, K.; Lavigne, G.J.; de Leeuw, R.; Manfredini, D.; Svensson, P.; Winocur, E. Bruxism defined and graded: An international consensus. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012, 40, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sateia, M.J. International Classification of Sleep Disorders-Third Edition. Chest 2014, 146, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics, 11th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: http://id.who.int/icd/entity/60908067 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Ferro, K.J.; Morgano, S.M.; Driscoll, C.F.; Freilich, M.A.; Guckes, A.D.; Knoernschild, K.L.; McGarry, T.J. The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms: Ninth Edition. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2017, 117 (Suppl. S5), e1–e105. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, N.; Fabbro, C.D. Sleep bruxism in children and adolescents-A scoping review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2024, 51, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J.P.; Moro, J.; Massignan, C.; Cardoso, M.; Serra-Negra, J.M.; Maia, L.C.; Bolan, M. Prevalence of clinical signs and symptoms of the masticatory system and their associations in children with sleep bruxism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 57, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, S.V.; de Souza, B.K.; Cruvinel, T.; Oliveira, T.M.; Neto, N.L.; Machado, M.A.A.M. Factors associated with preschool children’s sleep bruxism. Cranio® 2021, 42, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, P.F.; Erez, A.; Peretz, B.; Birenboim-Wilensky, R.; Winocur, E. Prevalence of bruxism and temporomandibular disorders among orphans in southeast Uganda: A gender and age comparison. Cranio® 2018, 36, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manfredini, D.; Restrepo, C.; Diaz-Serrano, K.; Winocur, E.; Lobbezoo, F. Prevalence of sleep bruxism in children: A systematic review of the literature. J. Oral Rehabil. 2013, 40, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, G.; Özçelik, C.; Türkoğlu, M.O.; Güven, M.Ç. Evaluation of the Prevalence of Bruxism and Parents Awareness in Children Aged 4-7: A Cross-Sectional Clinical Study. Turk. Klin. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 28, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, L.A.; Murray, J.; Tovo-Rodrigues, L.; Correa, M.B.; Barros, F.; de Oliveira, I.O.; Domingues, M.R.; Demarco, F.F.; Goettems, M.L. Possible sleep bruxism and hair cortisol in children: A birth cohort study. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 34, e14427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diéguez-Pérez, M.; Ticona-Flores, J.M.; Prieto-Regueiro, B. Prevalence of Possible Sleep Bruxism and Its Association with Social and Orofacial Factors in Preschool Population. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, A.B.; Rodrigues, R.S.; Simão, C.; de Araújo, R.P.; Figueiredo, J. Prevalence of Sleep Bruxism Reported by Parents/Caregivers in a Portuguese Pediatric Dentistry Service: A Retrospective Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.T.; Bittencourt, S.T.; Marcon, K.; Destro, S.; Pereira, J.R. Sleep bruxism and anxiety level in children. Braz. Oral Res. 2015, 29, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kryger, M.; Svensson, P.; Arima, T. Sleep bruxism: Definition, prevalence, classification, etiology, and consequences. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 6th ed.; Kryger, M., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 1423–1426. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne, G.; Manzini, C.; Huynh, N.T. Sleep bruxism. In Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine, 5th ed.; Kryger, M.H., Roth, T., Dement, W.C., Eds.; Elsevier Saunders: St Louis, MO, USA, 2011; pp. 1129–1139. [Google Scholar]

- Smardz, J.; Martynowicz, H.; Wojakowska, A.; Wezgowiec, J.; Danel, D.; Mazur, G.; Wieckiewicz, M. Lower serotonin levels in severe sleep bruxism and its association with sleep, heart rate, and body mass index. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, C.C.; Fernandez, M.d.S.; Jansen, K.; da Silva, R.A.; Boscato, N.; Goettems, M.L. Daily screen time, sleep pattern, and probable sleep bruxism in children: A cross-sectional study. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2888–2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flueraşu, M.I.; Bocşan, I.C.; Țig, I.-A.; Iacob, S.M.; Popa, D.; Buduru, S. The Epidemiology of Bruxism in Relation to Psychological Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolchev, B. Architecture of Normal (Physiological) Sleep. In Handbook of Sleep Medicine; East-West: Manhattan Beach, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chemelo, V.d.S.; Né, Y.G.d.S.; Frazão, D.R.; de Souza-Rodrigues, R.D.; Fagundes, N.C.F.; Magno, M.B.; da Silva, C.M.T.; Maia, L.C.; Lima, R.R. Is there association between stress and bruxism? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 590779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Balushi, B.; Essa, M.M. The Impact of COVID-19 on Children—Parent’s Perspective. Int. J. Nutr. Pharmacol. Neurol. Dis. 2020, 10, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharel, M.; Sakamoto, J.L.; Carandang, R.R.; Ulambayar, S.; Shibanuma, A.; Yarotskaya, E.; Basargina, M.; Jimba, M. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on movement behaviours of children and adolescents: A systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Emodi-Perlman, A.; Eli, I.; Smardz, J.; Uziel, N.; Wieckiewicz, G.; Gilon, E.; Grychowska, N.; Wieckiewicz, M. Temporomandibular disorders and bruxism outbreak as a possible factor of orofacial pain worsening during the COVID-19 pandemic-concomitant research in two countries. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur-Arias, O.; Winocur, E.; Shalev-Antsel, T.; Reiter, S.; Shifra, L.; Emodi-Perlman, A.; Friedman-Rubin, P. Painful temporomandibular disorders, bruxism and oral parafunctions before and during the COVID-19 pandemic era: A sex comparison among dental patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Xiang, M.; Cheung, T.; Xiang, Y.-T. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, B.G.; Luis, O.E.R.; Villarreal, S.M.L.; Cepeda, S.E.N.; Capetillo, E.G.T.; Morteo, L.T.; Ramirez, M.S.T.; Soto, J.M.S. Bruxism in pediatric dentistry during the pandemic COVID-19. Int. J. Appl. Dent. Sci. 2022, 8, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhari, S.; Gurunathan, D. Can National Lockdown Due to COVID-19 Be Considered As A Stress Factor for Bruxism in Children. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 8, 2056–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, C.; Santamaría, A.; Manrique, R. Sleep bruxism in children: Relationship with screen-time and sugar consumption. Sleep Med. X 2021, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo-Serna, C.; Caicedo-Giraldo, M.; Velasquez-Baena, L.; Bonfanti, G.; Santamaría-Villegas, A. Effect of Screen Time and Sugar Consumption Reduction on Sleep Bruxism in Children: A Randomised Clinical Trial. J. Oral Rehabil. 2025, 52, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Diaz, M.; Ortega-Martínez, A.R.; Romero-Maroto, M.; González-Olmo, M.J. Lockdown impact on lifestyle and its association with oral parafunctional habits and bruxism in a Spanish adolescent population. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2022, 32, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, L.C.M.; Leal, T.R.; de Araújo, L.J.S.; Sousa, M.L.C.; da Silva, S.E.; Serra-Negra, J.M.C.; Ferreira, F.d.M.; Paiva, S.M.; Granville-Garcia, A.F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleep quality and sleep bruxism in children eight to ten years of age. Braz. Oral Res. 2022, 36, e046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlăduțu, D.; Popescu, S.M.; Mercuț, R.; Ionescu, M.; Scrieciu, M.; Glodeanu, A.D.; Stănuși, A.; Rîcă, A.M.; Mercuț, V. Associations between Bruxism, Stress, and Manifestations of Temporomandibular Disorder in Young Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scariot, R.; Brunet, L.; Olsson, B.; Palinkas, M.; Regalo, S.C.H.; Rebellato, N.L.B.; Brancher, J.A.; Torres, C.P.; Diaz-Serrano, K.V.; Küchler, E.C.; et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms in dopamine receptor D2 are associated with bruxism and its circadian phenotypes in children. Cranio® 2019, 40, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurunathan, D. Impact of physical activity and screen time on occurrence of bruxism in children: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2014, 8, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisler, G.C.; Hasler, B.P.; Franzen, P.L.; Clark, D.B.; Twenge, J.M. Screen media use and sleep disturbance symptom severity in children. Sleep Health 2020, 6, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.D.; Barnes, J.D.; Chaput, J.P.; Tremblay, M.S. Screen time and problem behaviors in children: Exploring the mediating role of sleep duration. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nopembri, S.; Mulyawan, R.; Fauziah, P.Y.; Kusumawardani, E.; Susilowati, I.H.; Fauzi, L.; Cahyati, W.H.; Rahayu, T.; Chua, T.B.K.; Chia, M.Y.H. Time to Play in Javanese Preschool Children—An Examination of Screen Time and Playtime before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basuodan, R.M.; Gmmash, A.; Alghadier, M.; Albesher, R.A. Relationship between Pain, Physical Activity, Screen Time and Age among Young Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, S.L.; Banks, L.; Schneiderman, J.E.; Caterini, J.E.; Stephens, S.; White, G.; Dogra, S.; Wells, G.D. Physical activity for children with chronic disease; a narrative review and practical applications. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Screen Time | At the Current Time | During the Pandemic |

|---|---|---|

| Age Group | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| 3–6 years | 93.3 ± 67.8 | 150 ± 99.5 |

| 7–10 years | 126.6 ± 72.3 | 187 ± 110.8 |

| 11–14 years | 160.2 ± 93.9 | 226.8 ± 151.2 |

| Total | 141.8 ± 85.2 | 205 ± 133.1 |

| ANOVA | F = 6.811 p = 0.001 | F = 3.734 p = 0.025 |

| Tukey’s HSD | 7–10 Γ. vs. 11–14 Γ. (p = 0.004) | 7–10 Γ. vs. 11–14 Γ. (p = 0.045) |

| Children Screen Time (Minutes per Day) | Without Bruxism | With Bruxism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| 0 min | 11 | 5.2% | 1 | 1.9% |

| 30–120 min | 38 | 17.9% | 13 | 24.1% |

| 120–180 min | 130 | 61.3% | 28 | 51.9% |

| 180–360 min | 27 | 12.7% | 10 | 18.5% |

| 360 min and more | 4 | 1.9% | 5 | 9.3% |

| Total | 212 | 100% | 54 | 100% |

| χ2 = 14.67, p = 0.005 | ||||

| Screen time (mean value) | N | Mean ± SD | N | Mean ± SD |

| 212 | 135.3 ± 79.3 | 54 | 167.2 ± 102.2 | |

| t = 2.484 p = 0.014 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitova, N.; Dimitrova, M. Screen Time and Sleep Bruxism—A Comparison Between the Present Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children 2025, 12, 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101396

Mitova N, Dimitrova M. Screen Time and Sleep Bruxism—A Comparison Between the Present Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children. 2025; 12(10):1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101396

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitova, Nadezhda, and Marianna Dimitrova. 2025. "Screen Time and Sleep Bruxism—A Comparison Between the Present Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic" Children 12, no. 10: 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101396

APA StyleMitova, N., & Dimitrova, M. (2025). Screen Time and Sleep Bruxism—A Comparison Between the Present Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Children, 12(10), 1396. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101396