Understanding Pain and Quality of Life in Paediatric Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Early Survivorship

Abstract

Highlights

- Children and young people (CYP) who survive cancer—particularly females—are more likely than the general population to report acute and chronic pain in later life, and they frequently experience comorbidities such as fatigue, depression, and anxiety. Yet, their pain is often likely to be under-recognized, especially in childhood, partly due to a lack of developmentally sensitive assessment tools in CYP.

- This study demonstrates that the poor understanding of post-cancer treatment pain in children and young people (CYP) stems not only from the absence of adapted assessment tools but also from limited early post-treatment data. Together, these shortcomings create a significant gap in mapping CYP pain trajectories after cancer.

- Our findings highlight the urgent need for timely, rigorous, age-specific research to better inform survivorship care and shape evidence-based clinical policy. Our study also suggests that clinicians should routinely assess both acute and chronic pain in CYP cancer survivors using validated, age-appropriate tools in early post-treatment completion assessments.

Abstract

1. Introduction

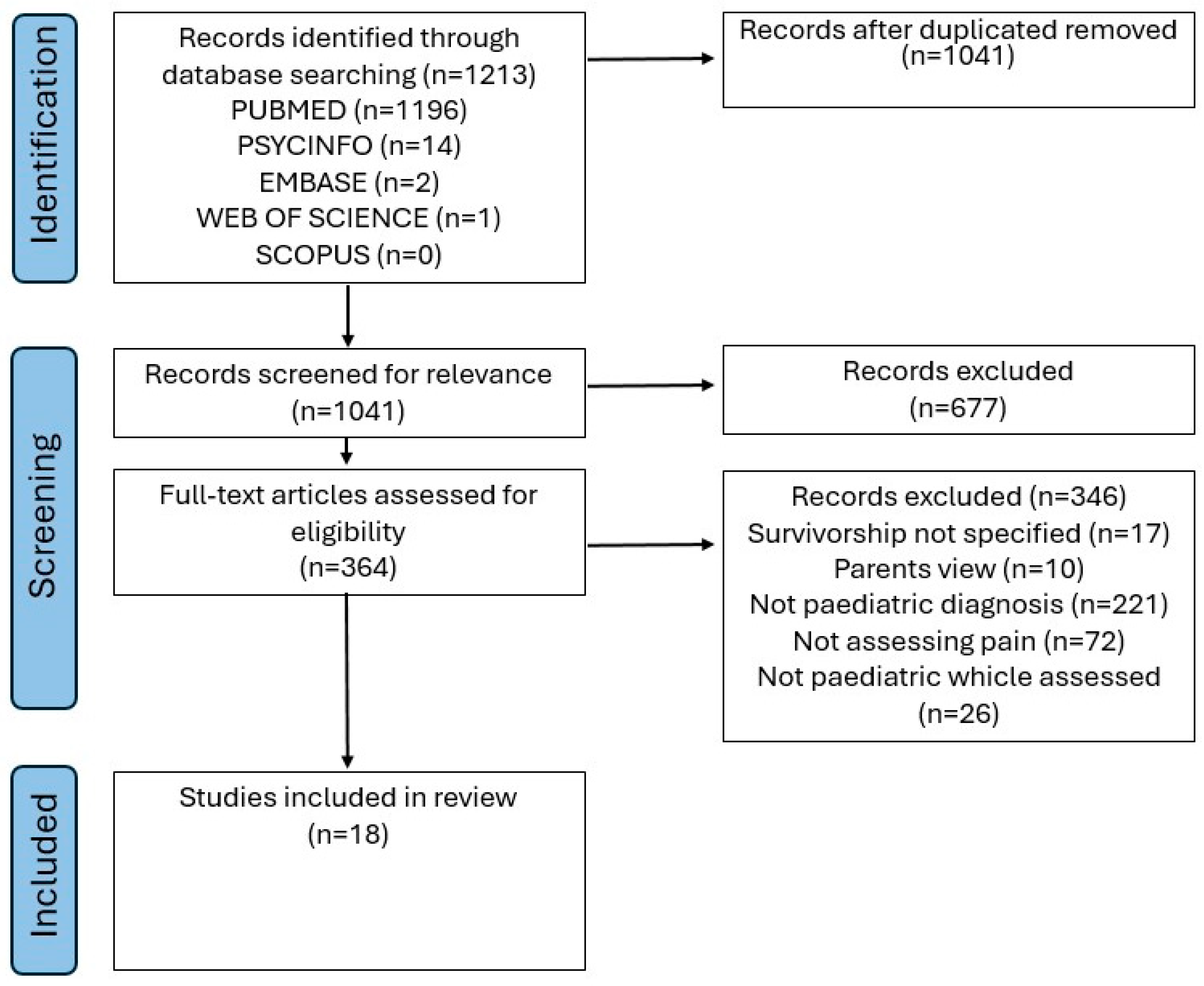

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Databases Searched

2.2. Endpoints

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

2.4. Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Data Extraction

3.2. Quality Assessment

3.3. Data Synthesis

3.3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3.2. Methods for Measuring Pain

3.4. Pain Prevalence

3.4.1. Chronic Pain

3.4.2. Acute Pain

3.4.3. Treatment-Related Pain

3.5. Pain Correlates

3.5.1. Biological

3.5.2. Psychological

3.5.3. Quality of Life

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Robison, L.L.; Hudson, M.M. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: Life-long risks and re-sponsibilities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.P.; Veiga, D.; Araújo, A. Chronic pain, functionality and quality of life in cancer survivors. Br. J. Pain 2020, 15, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treede, R.D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015, 155, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheel, E.; Heathcote, L.C.; Bosch, J.v.d.W.T.; Schulte, F.; Pate, J.W. Pain science education for children living with and beyond cancer: Challenges and research agenda. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2022, 69, e29783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, N.M.; Leisenring, W.; Whitton, J.; Stratton, K.; Jibb, L.; Flynn, J.; Pizzo, A.; Brinkman, T.M.; Birnie, K.; Gibson, T.M.; et al. Characterization of chronic pain, pain interference, and daily pain experiences in adult survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pain 2024, 165, 2530–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinfjell, T.; Zeltzer, L. A systematic review of self-reported pain in childhood cancer survivors. Acta Paediatr. 2020, 109, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlson, C.W.; Alberts, N.M.; Liu, W.; Brinkman, T.M.; Annett, R.D.; Mulrooney, D.A.; Schulte, F.; Leisenring, W.M.; Gibson, T.M.; Howell, R.M.; et al. Longitudinal pain and pain interference in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer 2020, 126, 2915–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutelman, P.R.; Chambers, C.T.; Stinson, J.N.; Parker, J.A.; Fernandez, C.V.; Witteman, H.O.; Nathan, P.C.; Barwick, M.; Campbell, F.; Jibb, L.A.; et al. Pain in Children with Cancer: Prevalence, Characteristics, and Parent Manage-ment. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, K.; Holley, S.; Schoth, D.E.; Harrop, E.; Howard, R.F.; Bayliss, J.; Brook, L.; Jassal, S.S.; Johnson, M.; Wong, I.; et al. A mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis of barriers and facilitators to paediatric symptom management at end of life. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 689–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahre, H.; Grotle, M.; Smedbråten, K.; Richardsen, K.R.; Côté, P.; Steingrímsdóttir, Ó.A.; Nielsen, C.; Storheim, K.; Småstuen, M.; Stensland, S.Ø.; et al. Low social acceptance among peers increases the risk of persistent musculoskeletal pain in adolescents. Prospective data from the Fit Futures Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurm, M.; Anniko, M.; Tillfors, M.; Flink, I.; Boersma, K. Musculoskeletal pain in early adolescence: A longitudinal examination of pain prevalence and the role of peer-related stress, worry, and gender. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 111, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palermo, T.M.; Chambers, C.T. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: An integrative approach. Pain 2005, 119, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liossi, C.; Howard, R.F. Pediatric Chronic Pain: Biopsychosocial Assessment and Formulation. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, T.M. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents; Oxford University Press (OUP): Oxford, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780199763979. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, T.M.; Valrie, C.R.; Karlson, C.W. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: A developmental perspec-tive. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liossi, C.; Johnstone, L.; Lilley, S.; Caes, L.; Williams, G.; Schoth, D.E. Effectiveness of interdisciplinary interventions in paediatric chronic pain management: A systematic review and subset meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e359–e371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, F.S.M.; Patton, M.; Alberts, N.M.; Kunin-Batson, A.; Olson-Bullis, B.A.; Forbes, C.; Russell, K.B.; Neville, A.; Heathcote, L.C.; Karlson, C.W.; et al. Pain in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A systematic review of the current state of knowledge and a call to action from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2020, 127, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.A.; Karunananthan, S.; Maxwell, L.J.; Akl, E.A.; Avey, M.T.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brouwers, M.C.; Clark, J.P.; Cook, S.; et al. When to replicate systematic reviews of interventions: Consensus checklist. BMJ 2020, 370, m2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Green, S.; Ben Van Den, A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 15, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, S.M.; Azzopardi, P.S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G.C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoth, D.E.; Holley, S.; Johnson, M.; Stibbs, E.; Renton, K.; Harrop, E.; Liossi, C. Home-based physical symptom management for family caregivers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2025, 15, 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpaci, T.; Toruner, E.K. Assessment of problems and symptoms in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2016, 25, 1034–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, C.; Hayashi, R.J. Participation and Self-Management Strategies of Young Adult Childhood Cancer Survivors. OTJR Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2012, 33, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, D.C.; Griffith, T.; Gargan, L.; Cochran, C.J.; Kleiber, B.; Foxwell, A.; Farrow-Gillespie, A.; Orlino, A.; Germann, J.N. Back Pain Among Long-term Survivors of Childhood Leukemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 34, 624–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkman, T.M.; Li, C.; Vannatta, K.; Marchak, J.G.; Lai, J.-S.; Prasad, P.K.; Kimberg, C.; Vuotto, S.; Di, C.; Srivastava, D.; et al. Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Symptom Comorbidities and Profiles in Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 3417–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crom, D.B.; Smith, D.; Xiong, Z.; Onar, A.; Hudson, M.M.; Merchant, T.E.; Morris, E.B. Health Status in Long-Term Survivors of Pediatric Craniopharyngiomas. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2010, 42, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feeny, D.L.A.; Leiper, A.; Barr, R.D.; Furlong, W.; Torrance, G.W.; Rosenbaum, P.; Weitzman, S. The comprehensive assessment of health status in survivors of childhood cancer: Application to high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Cancer 1993, 67, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Chiou, S.; Hsu, H.-T.; Lin, P.; Liao, Y.; Wu, L.-M. Adverse health outcomes and health concerns among survivors of various childhood cancers: Perspectives from mothers. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 27, e12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.B.; Hudson, M.M.; Ledet, D.S.; Morris, E.B.; Pui, C.-H.; Howard, S.C.; Krull, K.R.; Hinds, P.S.; Crom, D.; Browne, E.; et al. Neurologic morbidity and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A prospective cross-sectional study. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranick, S.M.; Campen, C.J.; Kasner, S.E.; Kessler, S.K.; Zimmerman, R.A.; Lustig, R.A.; Phillips, P.C.; Beslow, L.A.; Ichord, R.; Fisher, M.J. Headache as a risk factor for neurovascular events in pediatric brain tumor pa-tients. Neurology 2013, 16, 1452–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, K.A.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Kawashima, T.; Oeffinger, K.C.; Woods, W.G.; Nicholson, S.; Neglia, J.P. Health conditions and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leu-kemia comparing post remission chemotherapy to BMT: A report from the children’s oncology group. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2014, 61, 729–736. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, S.; Blankenburg, M.; Apel, K.; Hirschfeld, G.; Driever, P.H.; Reindl, T. Small-fiber neuropathy and pain sensitization in survivors of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2018, 22, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odame, I.; Duckworth, J.; Talsma, D.; Ba, L.B.; Furlong, W.; Webber, C.; Barr, R. Osteopenia, physical activity and health-related quality of life in survivors of brain tumors treated in childhood. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2005, 46, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portwine, C.; Rae, C.; Davis, J.; Teira, P.; Schechter, T.; Lewis, V.; Mitchell, D.; Wall, D.A.; Pullenayegum, E.; Barr, R.D. Health-Related Quality of Life in Survivors of High-Risk Neuroblastoma After Stem Cell Transplant: A National Population-Based Perspective. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1615–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, E.M.; Van Dulmen-den Broeder, E.; Kaspers, G.J.; Van Dam, E.W.C.M.; Braam, K.I.; Huisman, J. Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2008, 17, 506–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revel-Vilk, S.; Menahem, M.; Stoffer, C.; Weintraub, M. Post-thrombotic syndrome after central venous catheter removal in childhood cancer survivors is associated with a history of obstruction. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2010, 55, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadighi, Z.S.; Ness, K.K.; Hudson, M.M.; Morris, E.B.; Ledet, D.S.; Pui, C.-H.; Howard, S.C.; Krull, K.R.; Browne, E.; Crom, D.; et al. Headache types, related morbidity, and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A prospective cross sectional study. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2014, 18, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.A.; Mao, J.J.; DeRosa, B.W.; Ginsberg, J.P.; Hobbie, W.L.; Carlson, C.A.; Mougianis, I.D.; Ogle, S.K.; Kazak, A.E. Self-Reported Health Problems of Young Adults in Clinical Settings: Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Healthy Controls. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2010, 23, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.W.; Effinger, K.E.; Wasilewski-Masker, K.; Mertens, A.; Xiao, C. Self-reported late effect symptom clusters among young pediatric cancer survivors. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 8077–8087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, C.J.; Campbell, C.M.; Edwards, R.R.; Dobs, A.S. Sex-Based Differences in Pain Perception and Treatment. Pain Med. 2009, 10, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.T.; Dol, J.; Tutelman, P.R.; Langley, C.L.; Parker, J.A.; Cormier, B.T.; Macfarlane, G.J.; Jones, G.T.; Chapman, D.; Proudfoot, N.; et al. The prevalence of chronic pain in children and adolescents: A systematic review update and meta-analysis. Pain 2024, 165, 2215–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Q.; Tsao, J.; Leisenring, W.; Zeltzer, L.; Robison, L.; Armstrong, G. A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS): Cancer related posttraumatic stress symptoms, depression, anxiety, and chronic pain in adult childhood cancer survivors. J. Pain 2009, 10, S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoth, D.E.; Blankenburg, M.; Wager, J.; Zhang, J.; Broadbent, P.; Radhakrishnan, K.; van Jole, O.; Lyle, G.L.; Laycock, H.; Zernikow, B.; et al. Quantitative sensory testing in paediatric patients with chronic pain: A systematic re-view and meta-analysis. Br. J. Anaesth. 2022, 129, e94–e97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liossi, C.; Laycock, H.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Hussain, Z.; Schoth, D.E. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Conditioned Pain Modulation in Children and Young People with Chronic Pain. Children 2024, 11, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąbel, P.; Pieniążek, L.; Zarotyński, D. The effect of the type of pain on the accuracy of memory of pain and affect. Eur. J. Pain 2015, 19, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population (P) | Children diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 0 and 21 years; survivors aged 2–24 years who were at least 5 years post-diagnosis and/or 2 years post-completion of therapy. | Children diagnosed after the age of 21; survivors older than 24 years. |

| Intervention (I) | All cancer-related treatments. | Studies not within 5 years post-diagnosis and/or 2 years post-completion of therapy. |

| Comparator (C) | Studies with and without a comparison group. | None. |

| Outcomes (O) | Acute and chronic pain, quality of life, and psychological outcomes. | Studies in which pain was not assessed at all. |

| Study design (S) | Randomized controlled trials and cohort studies. | Reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, dissertations, books, book chapters, letters, and case studies. |

| Study | Confounding | Participant Selection | Intervention Classification | Missing Data | Outcome Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arpaci T. [25] | X | + | - | - | X |

| Berg C. [26] | - | + | X | - | + |

| Bowers DC. [27] | X | + | X | + | + |

| Brinkman TM. [28] | X | X | X | - | + |

| Crom DB. [29] | - | X | X | - | + |

| Feeny D. [30] | X | - | - | - | + |

| Hsiao CC. [31] | X | X | X | - | + |

| Khan BR. [32] | - | + | X | - | + |

| Kranick SM. [33] | X | + | - | - | X |

| Schultz KAP. [34] | - | + | X | - | X |

| Lieber S. [35] | - | + | X | - | - |

| Odame I. [36] | - | + | X | - | + |

| Portwine C. [37] | - | + | X | - | + |

| Van Dijk EM. [38] | X | X | X | - | X |

| Revel-Vilk S. [39] | X | X | X | - | X |

| Sadighi Z. [40] | X | + | X | - | + |

| Schwartz LA. [41] | X | + | X | - | + |

| Williamson LR. [42] | X | X | X | - | X |

| Health-related quality of life or health status measures | 14 (77.77%) |

| Valid pain measures | 1 (5.5%) |

| Chart review | 1 (5.5%) |

| Author-created measures | 5 (27.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Domenico, F.; Liossi, C.; Géranton, S.M. Understanding Pain and Quality of Life in Paediatric Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Early Survivorship. Children 2025, 12, 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101320

Di Domenico F, Liossi C, Géranton SM. Understanding Pain and Quality of Life in Paediatric Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Early Survivorship. Children. 2025; 12(10):1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101320

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Domenico, Francesca, Christina Liossi, and Sandrine Martine Géranton. 2025. "Understanding Pain and Quality of Life in Paediatric Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Early Survivorship" Children 12, no. 10: 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101320

APA StyleDi Domenico, F., Liossi, C., & Géranton, S. M. (2025). Understanding Pain and Quality of Life in Paediatric Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review with a Focus on Early Survivorship. Children, 12(10), 1320. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12101320