Attendance in a Neonatal Follow-Up Program before and in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Prospective–Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics before and after the Onset of COVID-19

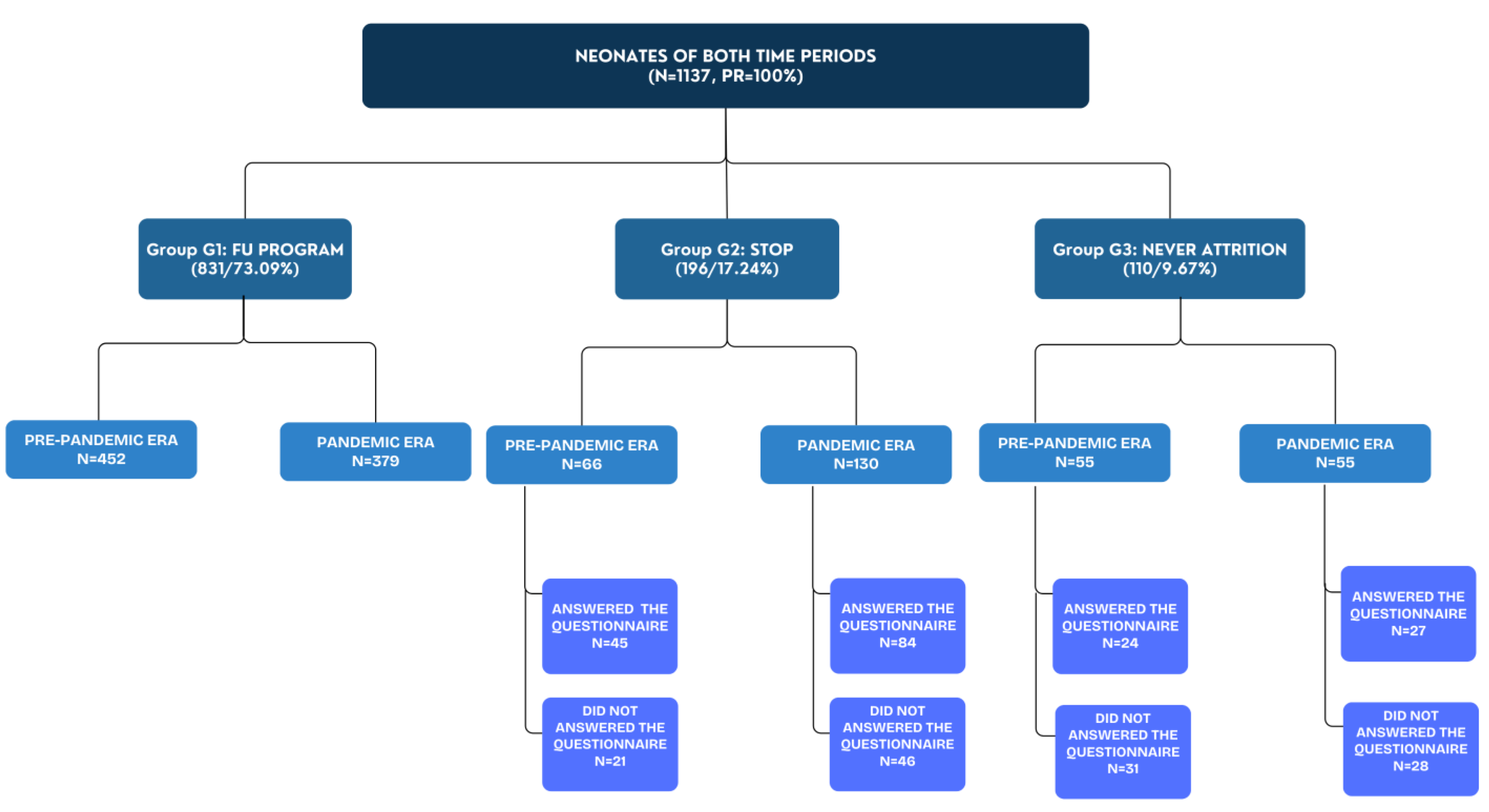

3.2. Attendance Rates before and after the Onset of COVID-19

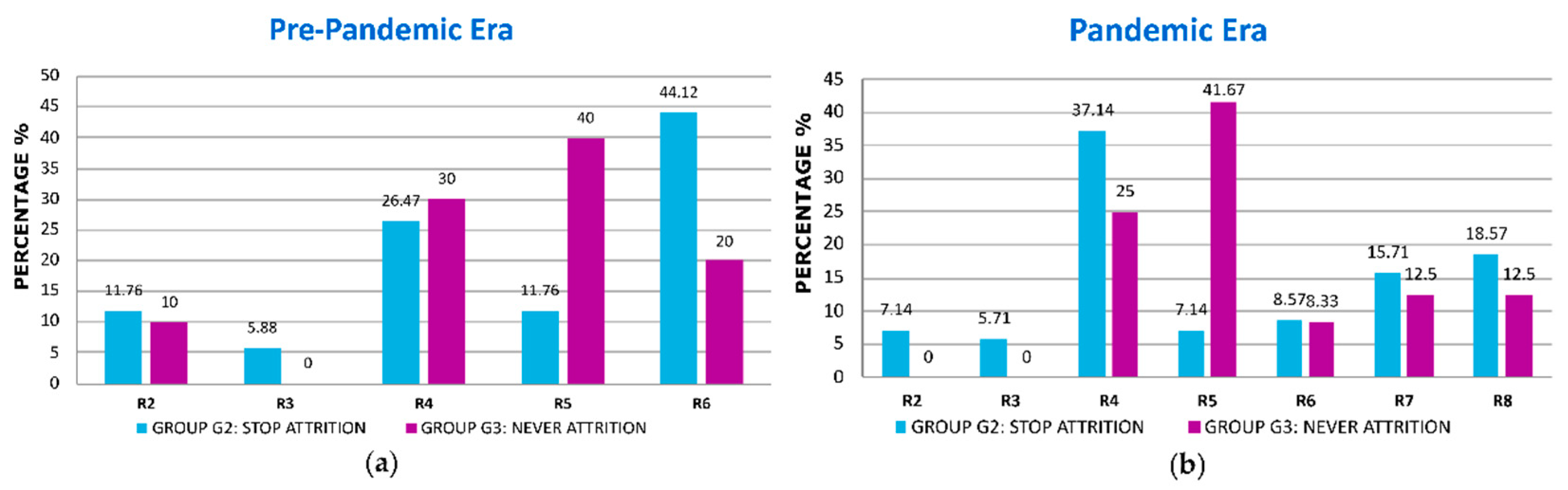

3.2.1. Reasons for Non-Attendance

3.2.2. Comparisons between Groups before the Onset of COVID-19

3.2.3. Comparisons between Groups after the Onset of COVID-19

3.2.4. Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Blencowe, H.; Cousens, S.; Oestergaard, M.Z.; Chou, D.; Moller, A.-B.; Narwal, R.; Adler, A.; Garcia, C.V.; Rohde, S.; Say, L.; et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. Lancet 2012, 379, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preterm Birth [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/preterm-birth (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- McCormick, M.C.; Litt, J.S.; Smith, V.C.; Zupancic, J.A.F. Prematurity: An Overview and Public Health Implications. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litt, J.S.; Campbell, D.E. High-Risk Infant Follow-Up after NICU Discharge. Clin. Perinatol. 2023, 50, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spittle, A.; Treyvaud, K. The role of early developmental intervention to influence neurobehavioral outcomes of children born preterm. Semin. Perinatol. 2016, 40, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, K.; Greene, M.M.; Perez, B.; Silvestri, J.M. Neonatal high-risk follow-up clinics: How to improve attendance in very low birth weight infants. E-J. Neonatal Res. 2014, 4, 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, E.C.; Vohr, B.R. Neurodevelopmental Follow-up of Preterm Infants. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 66, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, I.B.; Melwak, M.A. Who Is at Risk? High-Risk Infant Follow-up. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2012, 12, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orton, J.; Spittle, A.; Doyle, L.; Anderson, P.; Boyd, R. Do early intervention programmes improve cognitive and motor outcomes for preterm infants after discharge? A systematic review: Early Intervention for Preterm Infants. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2009, 51, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, L.W.; Anderson, P.J.; Battin, M.; Bowen, J.R.; Brown, N.; Callanan, C.; Campbell, C.; Chandler, S.; Cheong, J.; Darlow, B.; et al. Long term follow up of high risk children: Who, why and how? BMC Pediatr. 2014, 14, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, L.; Winter, S.; Byrne, R.; Fehlings, D.; Gehred, A.; Letzkus, L.; Noritz, G.; Paton, M.C.; Pietruszewski, L.; Rosenberg, N.; et al. Assessments and Interventions for Spasticity in Infants with or at High Risk for Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic Review. Pediatr. Neurol. 2021, 118, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppala, V.S.; Tabangin, M.; Haberman, B.; Steichen, J.; Yolton, K. Current state of high-risk infant follow-up care in the United States: Results of a national survey of academic follow-up programs. J. Perinatol. 2012, 32, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, B. The State of Neonatal Follow-Up Programs. In Follow-Up for NICU Graduates: Promoting Positive Developmental and Behavioral Outcomes for At-Risk Infants; Needelman, H., Jackson, B.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohr, B.R.; O’Shea, M.; Wright, L.L. Longitudinal multicenter follow-up of high-risk infants: Why, who, when, and what to assess. Semin. Perinatol. 2003, 27, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhutta, A.T.; Cleves, M.A.; Casey, P.H.; Cradock, M.M.; Anand, K.J.S. Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of School-Aged Children Who Were Born Preterm: A Meta-analysis. JAMA 2002, 288, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitre, N.L.; Duncan, A.F. Neurologic and Developmental Outcomes of High-Risk Neonates. Clin. Perinatol. 2023, 50, xxi–xxii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perenyi, A.; Katz, J.; Flom, P.; Regensberg, S.; Sklar, T. Analysis of compliance, morbidities and outcome in neurodevelopmental follow-up visits in urban African-American infants at environmental risk. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2010, 1, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Lee, H.; Gray, E.; Gould, J.; Hintz, S. Programmatic and Administrative Barriers to High-Risk Infant Follow-Up Care. Am. J. Perinatol. 2018, 35, 940–945. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, M.; Stevens, B.; Guttmann, A.; Willan, A.R.; Rosenbaum, P. Transition to Neonatal Follow-up Programs: Is Attendance a Problem? J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2012, 26, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, S.L.; Conaway, M.; Sinkin, R.A.; Blackman, J.A. Factors associated with neonatal intensive care follow-up appointment compliance. Clin. Pediatr. 2013, 52, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, J.M.; Pouppirt, N.; Bernbaum, J.; D’Agostino, J.A.; Gerdes, M.; Hoffman, C.; Cook, N.; Hurt, H.; Kirpalani, H.; DeMauro, S.B. Why do children with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia not attend neonatal follow-up care? Parental views of barriers. Acta Paediatr. 2018, 107, 996–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearingen, C.; Simpson, P.; Cabacungan, E.; Cohen, S. Social disparities negatively impact neonatal follow-up clinic attendance of premature infants discharged from the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMauro, S.B.; Bellamy, S.L.; Fernando, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Gratton, T.; Schmidt, B.; PROP Investigators. Patient, Family, and Center-Based Factors Associated with Attrition in Neonatal Clinical Research: A Prospective Study. Neonatology 2019, 115, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, E.D.; Tavares, T.S.; Cardoso, I.V.L.; Vieira, C.S.; Guimarães, B.R.; Bueno, M. Factors associated with the discontinuance of outpatient follow-up in neonatal units. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballantyne, M.; Benzies, K.; Rosenbaum, P.; Lodha, A. Mothers’ and health care providers’ perspectives of the barriers and facilitators to attendance at Canadian neonatal follow-up programs. Child. Care Health Dev. 2015, 41, 722–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintz, S.R.; Gould, J.B.; Bennett, M.V.; Lu, T.; Gray, E.E.; Jocson, M.A.L.; Fuller, M.G.; Lee, H.C. Factors Associated with Successful First High-Risk Infant Clinic Visit for Very Low Birth Weight Infants in California. J. Pediatr. 2019, 210, 91–98.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballantyne, M.; Stevens, B.; Guttmann, A.; Willan, A.R.; Rosenbaum, P. Maternal and infant predictors of attendance at Neonatal Follow-Up programmes. Child. Care Health Dev. 2014, 40, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.H.; Youn, Y.A.; Cho, S.J.; Hwang, J.-H.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, E.A.-R.; Lee, S.M.; Network, K.N. The predictors for the non-compliance to follow-up among very low birth weight infants in the Korean neonatal network. Gurgel RQ, editor. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehra, V.; Pici, M.; Visintainer, P.; Kase, J.S. Indicators of compliance for developmental follow-up of infants discharged from a regional NICU. J. Perinat. Med. 2009, 37, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuczyńska, M.; Matthews-Kozanecka, M.; Baum, E. Accessibility to Non-COVID Health Services in the World During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Review. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 760795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Biase, S.; Cook, L.; Skelton, D.A.; Witham, M.; ten Hove, R. The COVID-19 rehabilitation pandemic. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondilis, E.; Tarantilis, F.; Benos, A. Essential public healthcare services utilization and excess non-COVID-19 mortality in Greece. Public Health 2021, 198, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberton, T.; Carter, E.D.; Chou, V.B.; Stegmuller, A.R.; Jackson, B.D.; Tam, Y.; Sawadogo-Lewis, T.; Walker, N. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: A modelling study. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e901–e908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdei, C.; Liu, C.H. The downstream effects of COVID-19: A call for supporting family wellbeing in the NICU. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 1283–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazzi, E.; Galli, J. New clinical needs and strategies for care in children with neurodisability during COVID-19. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 879–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraiman, Y.S.; Edwards, E.M.; Horbar, J.D.; Mercier, C.E.; Soll, R.F.; Litt, J.S. Racial Inequity in High-Risk Infant Follow-Up among Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2022057865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, M.G.; Lu, T.; Gray, E.E.; Jocson, M.A.L.; Barger, M.K.; Bennett, M.; Lee, H.C.; Hintz, S.R. Rural Residence and Factors Associated with Attendance at the Second High-Risk Infant Follow-up Clinic Visit for Very Low Birth Weight Infants in California. Am. J. Perinatol. 2023, 40, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, M.A.; Gates, M.R.; Iatrow, A.M.; Lang, S.W.; Bratton, S.L. Barriers to Screening Infants for Retinopathy of Prematurity after Discharge or Transfer from a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Perinatol. 2005, 25, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Somu, R.; Maitre, N.; Levin, G.; Singh, A.P. Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on High-Risk Infant Follow-Up (HRIF) Programs: A Survey of Academic Programs. Children 2021, 8, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H.J.; Harris, R.M.; Krehbiel, C.; Banks, B.; Jackson, B.; Needelman, H. Examining disparities in the long term follow-up of Neonatal Intensive Care Unit graduates in Nebraska, U.S.A. J. Neonatal. Nurs. 2016, 22, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, L.; Woods, C.W.; Cutler, A.; DiPalazzo, J.; Craig, A.K. Telemedicine Improves Rate of Successful First Visit to NICU Follow-up Clinic. Hosp. Pediatr. 2023, 13, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporali, C.; Pisoni, C.; Naboni, C.; Provenzi, L.; Orcesi, S. Challenges and opportunities for early intervention and neurodevelopmental follow-up in preterm infants during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child. Care Health Dev. 2021, 47, 140–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christner, L.P.; Irani, S.; McGowan, C.; Dabaja, E.; Dejong, C.; Attar, M.A. Previous missed visits and independent risk of loss to follow-up in the high-risk neonatal follow-up clinic. Early Hum. Dev. 2023, 183, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reasons for Νon-Attendance (R) | Categorization |

|---|---|

| R1 | Lack of health insurance. |

| R2 | Accessibility (distance of the clinic from the permanent residence/lack of means of transport/change in residence/moving (to another region/country)/bad weather. |

| R3 | Loaded parental/family work schedule. |

| R4 | Obstacles related to hospital services (limited availability during clinic hours/difficulty with parking/long waiting time/bad communication with the secretariat/disappointment from the experience at the hospital. Change (cancelation or postponement) either after consultation (with the Hospital/with Papageorgiou’s doctors) or at the initiative of the parents, closed outpatient clinics due to COVID-19. |

| R5 | Negligence–Absence of Specific Reason. |

| R6 | Assessment by the parents that monitoring/FU appointment was unnecessary. |

| R7 | Health issues/Death in the family. |

| R8 | Fear of diseases exposure (to COVID-19 or other diseases)/Difficulties due to COVID-19 (“Because only one parent was allowed to accompany” or difficulty with Rapid Tests). |

| Characteristics | Pre-Pandemic Era (n = 573) | Pandemic Era (n = 564) | p | OR and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male) a | 315 (54.97) | 283 (50.18) | 0.1091 | 0.82 (0.65–1.04) |

| Birth weight (gr) a | 2090 (1620–2830) | 1830 (1430–2490) | 0.0005 | NA |

| Gestational age (weeks) a | 34.6 (32–37.3) | 33.1 (31.4–35.7) | 0.0003 | NA |

| Age of mother a | 32 (29–38) | 33 (29–38) | 0.3454 | NA |

| Multiparity a | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.4379 | NA |

| Multiple Gestation b | 104 (34.9) | 137 (34.25) | 0.8724 | 0.97 (0.71–1.33) |

| Small for Gestational Age (SGA) b | 72 (25.09) | 80 (20.89) | 0.2256 | 0.79 (0.55–1.13) |

| Gestational Hypertension b | 30 (11.03) | 55 (14.82) | 0.1947 | 1.4 (0.87–2.26) |

| Gestational Diabetes b | 34 (13.08) | 127 (36.6) | <0.0001 | 3.84 (2.52–5.85) |

| IntraUterine Growth Retardation (IUGR) b | 54 (19.85) | 94 (25.34) | 0.1078 | 1.37 (0.94–2) |

| Delivery mode: Cesarean Section (CS) b | 235 (80.48) | 317 (83.42) | 0.3607 | 0.82 (0.55–1.22) |

| Antenatal Steroid Administration (ASA) b | 62 (26.72) | 137 (37.53) | 0.0075 | 1.65 (1.15–2.36) |

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome b | 87 (29.49) | 173 (42.3) | 0.0005 | 1.75 (1.28–2.41) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia b | 29 (9.83) | 44 (10.76) | 0.7092 | 1.11 (0.67–1.81) |

| Early onset sepsis (<=3 DOL) b | 35 (12.07) | 13 (3.32) | <0.0001 | 0.25 (0.13–0.48) |

| Late onset sepsis (>3 DOL) b | 38 (13.1) | 73 (18.39) | 0.0742 | 1.49 (0.98–2.29) |

| Jaundice b | 236 (64.13) | 277 (63.68) | 0.9412 | 0.98 (0.73–1.31) |

| Necrotizing Enterocolitis b | 6 (2.08) | 15 (3.87) | 0.2623 | 1.9 (0.73–4.95) |

| Retinopathy of Prematurity b | 7 (2.45) | 8 (2.04) | 0.7941 | 0.83 (0.3–2.31) |

| Number of visits a | 1 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0.8534 | NA |

| Nationality (Foreign) b | 64 (11.17) | 67 (11.88) | 0.7114 | 0.93 (0.65–1.34) |

| Characteristics | G1 Group (n = 451) | G2 Group (n = 66) | G3 Group (n = 53) | G1 vs. G2 | G1 vs. G3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | ||||

| Number of visits a | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–3) | 0 (0–0) | 0.329605 | NA | <0.0001 | NA |

| Birth weight (gr) a | 2115 (1620–2835) | 1750 (1355–2400) | 2282.5 (1917.5–3290) | 0.008906 | NA | 0.0264 | NA |

| Gestational age (weeks) a | 34.6 (32.1–37.1) | 32.9 (29.7–35.6) | 36.3 (33–38.3) | 0.002245 | NA | 0.0108 | NA |

| Antenatal Steroid Administration (ASA) b | 43 (29.25) | 14 (30.44) | 3 (8.11) | 0.86 | 1.06 (0.51–2.18) | 0.0097 | 4.76 (1.37–16.67) |

| Multiparity a | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2.5) | 0.422272 | NA | <0.0001 | NA |

| Multiple Gestation b | 71 (38.17) | 22 (37.93) | 9 (17.31) | 1 | 0.99 (0.54–1.82) | 0.0047 | 2.94 (1.35–6.25) |

| Jaundice b | 169 (67.33) | 43 (69.36) | 23 (43.4) | 0.8796 | 1.1 (0.6–2) | 0.0016 | 2.70 (1.47–5) |

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome b | 54 (29.67) | 23 (38.98) | 8 (15.38) | 0.2005 | 1.51 (0.82–2.79) | 0.0493 | 2.33 (1.02–5.26) |

| Nationality (Foreign) b | 42 (9.31) | 9 (13.64) | 13 (24.53) | 0.2706 | 0.65 (0.3–1.41) | 0.0037 | 3.13 (1.56–6.25) |

| Characteristics | G1 Group (n = 451) | G2 Group (n = 66) | G3 Group (n = 53) | G1 vs. G2 | G1 vs. G3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | OR (95% CI) | p | ||||

| Number of visits a | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–3) | 0 (0–0) | 0.0006 | NA | 0.05 |

| Birth weight (gr) a | 1830 (1420–2430) | 1710 (1410–2250) | 2142.5 (1600–2660) | 0.3045 | NA | 0.0373 |

| Gestational age (weeks) a | 33.3 (31.1–36) | 32.4 (30.9–34.7) | 34.4 (33–37.4) | 0.1450 | NA | 0.0030 |

| Multiparity a | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (1–3) | 0.1980 | NA | 0.0091 |

| Jaundice b | 183 (68.03) | 76 (63.87) | 18 (38.3) | 0.4833 | NA | 0.0001 |

| Late onset sepsis (>3 DOL) b | 37 (16.02) | 34 (28.33) | 2 (4.35) | 0.0100 | 0.48 (0.28–0.82) | 0.0372 |

| Necrotizing Enterocolitis b | 6 (2.64) | 9 (7.76) | 0 (0) | 0.0467 | 0.32 (0.11–0.93) | 0.5936 |

| Respiratory Distress Syndrome b | 108 (44.81) | 53 (44.17) | 12 (25) | 1 | NA | 0.0155 |

| Hours of work b | 40 (20–40) | 40 (0–40) | 17.5 (0–40) | 0.2736 | NA | 0.0239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nantsi, E.; Chatziioannidis, I.; Pouliakis, A.; Mitsiakos, G.; Kondilis, E. Attendance in a Neonatal Follow-Up Program before and in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Prospective–Retrospective Observational Study. Children 2024, 11, 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091138

Nantsi E, Chatziioannidis I, Pouliakis A, Mitsiakos G, Kondilis E. Attendance in a Neonatal Follow-Up Program before and in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Prospective–Retrospective Observational Study. Children. 2024; 11(9):1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091138

Chicago/Turabian StyleNantsi, Evdoxia, Ilias Chatziioannidis, Abraham Pouliakis, Georgios Mitsiakos, and Elias Kondilis. 2024. "Attendance in a Neonatal Follow-Up Program before and in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Prospective–Retrospective Observational Study" Children 11, no. 9: 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091138

APA StyleNantsi, E., Chatziioannidis, I., Pouliakis, A., Mitsiakos, G., & Kondilis, E. (2024). Attendance in a Neonatal Follow-Up Program before and in the Time of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed Prospective–Retrospective Observational Study. Children, 11(9), 1138. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11091138