Physical Activity-Related Practices and Psychosocial Factors of Childcare Educators: A Latent Profile Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Practices and Psychosocial Factors

2.2.2. Provision of Physical Activity

2.2.3. Educator Characteristics

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

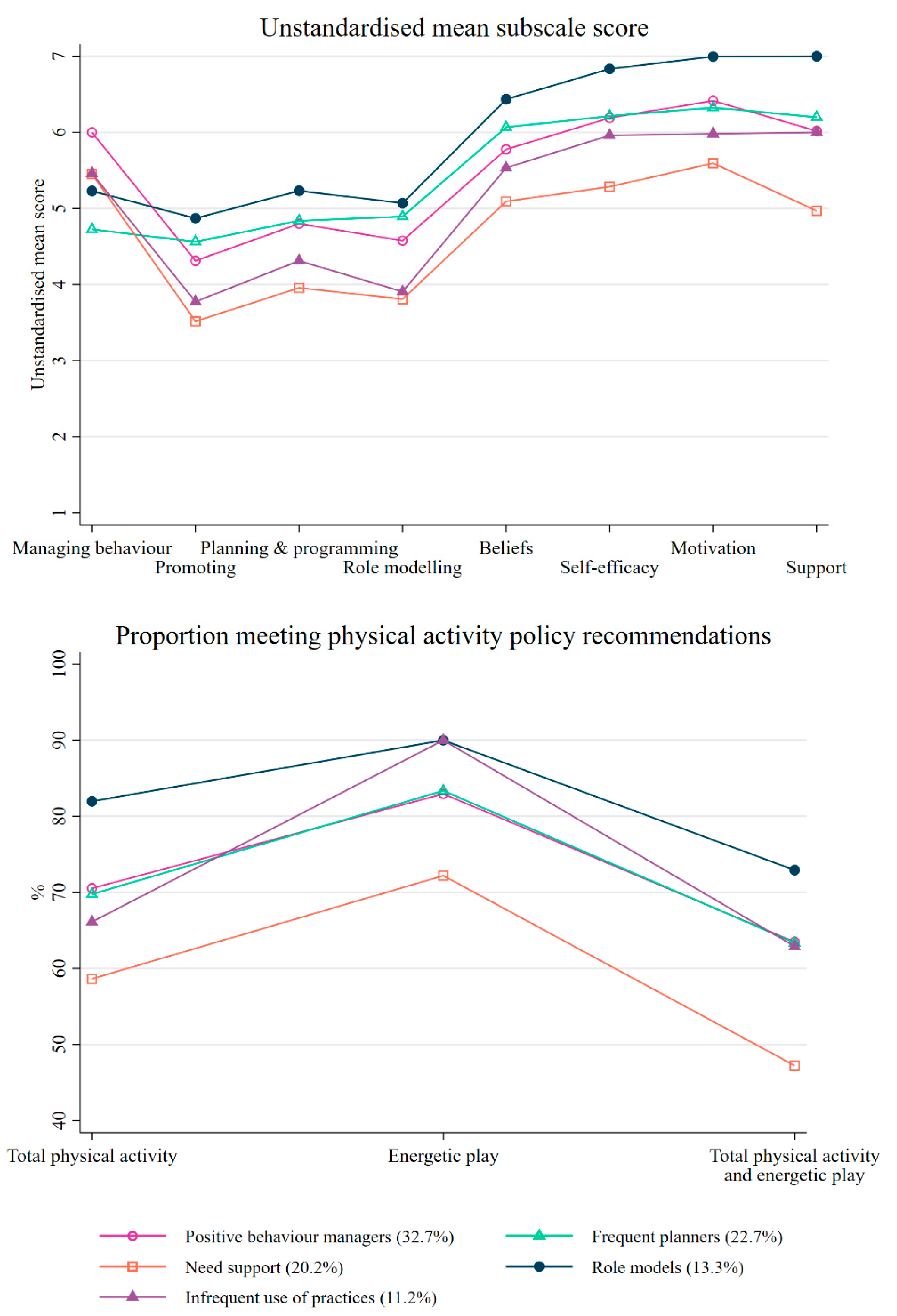

3.1. Latent Profiles

3.2. Association between Educator Profiles and Provision of Physical Activity

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carson, V.; Lee, E.-Y.; Hewitt, L.; Jennings, C.; Hunter, S.; Kuzik, N.; Stearns, J.A.; Unrau, S.P.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.; et al. Systematic review of the relationships between physical activity and health indicators in the early years (0–4 years). BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollo, S.; Antsygina, O.; Tremblay, M.S. The whole day matters: Understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 9, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Population-Based Approaches to Childhood Obesity Prevention; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roman-Viñas, B.; Chaput, J.-P.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Fogelholm, M.; Lambert, E.V.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; Olds, T.; Onywera, V.; Sarmiento, O.L.; et al. Proportion of children meeting recommendations for 24-hour movement guidelines and associations with adiposity in a 12-country study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2016, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hnatiuk, J.A.; Salmon, J.; Hinkley, T.; Okely, A.D.; Trost, S. A review of preschool children’s physical activity and sedentary time using objective measures. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 47, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Zheng, C.; Sit, C.H.; Reilly, J.J.; Huang, W.Y. Associations between meeting 24-hour movement guidelines and health in the early years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 2545–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Sallis, J.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E. Ecological models of health behavior. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Prioritizing Areas for Action in the Field of Population-Based Prevention of Childhood Obesity: A Set of Tools for Member States to Determine and Identify Priority Areas for Action; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Education at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. Child Care in Australia Report June Quarter 2021. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/early-childhood/early-childhood-data-and-reports/quarterly-reports-usage-services-fees-and-subsidies/child-care-australia-report-june-quarter-2021#:~:text=In%20the%20June%20quarter%202021%2C%2046.4%20per%20cent%20of%20children,approximately%20three%20days%20per%20week (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). Available online: https://www.acecqa.gov.au/ (accessed on 26 August 2022).

- Ellis, Y.G.; Cliff, D.P.; Janssen, X.; Jones, R.A.; Reilly, J.J.; Okely, A.D. Sedentary time, physical activity and compliance with IOM recommendations in young children at childcare. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, P. The physical activity levels of preschool-aged children: A systematic review. Early Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, J.J. Low levels of objectively measured physical activity in preschoolers in child care. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, N.; Ward, D.S.; Neelon, S.B.; Story, M. What Role Can Child-Care Settings Play in Obesity Prevention? A Review of the Evidence and Call for Research Efforts. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1343–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Standards for Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep in Early Childhood Education and Care Settings: A Toolkit; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, C.; Ball, S.C.; Benjamin, S.E.; Hales, D.; Vaughn, A.; Ward, D.S. Best-Practice Guidelines for Physical Activity at Child Care. Pediatrics 2009, 124, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, L.; Boudreau-Larivière, C.; Cimon-Lambert, K. Promoting Physical Activity in Preschoolers: A Review of the Guidelines, Barriers, and Facilitators for Implementation of Policies and Practices. Can. Psychol. 2012, 53, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L.; Finch, M.; Nathan, N.; Weaver, N.; Wiggers, J.; Yoong, S.L.; Jones, J.; Dodds, P.; Wyse, R.; Sutherland, R.; et al. Factors associated with early childhood education and care service implementation of healthy eating and physical activity policies and practices in Australia: A cross-sectional study. Transl. Behav. Med. 2015, 5, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfenden, L.; Barnes, C.; Jones, J.; Finch, M.; Wyse, R.J.; Kingsland, M.; Tzelepis, F.; Grady, A.; Hodder, R.K.; Booth, D.; et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD011779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, H.E.; Cross, D.; Rosenberg, M.; Schipperijn, J.; Shilton, T.; Trapp, G.; Trost, S.G.; Nathan, A.; Maitland, C.; Thornton, A.; et al. Development of physical activity policy and implementation strategies for early childhood education and care settings using the Delphi process. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Bélanger, M.; Donovan, D.; Carrier, N. Systematic review of the relationship between childcare educators’ practices and preschoolers’ physical activity and eating behaviours. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 1055–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, K.A.; Kendeigh, C.A.; Saelens, B.E.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Sherman, S.N. Physical activity in child-care centers: Do teachers hold the key to the playground? Health Educ. Res. 2012, 27, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfield, G.S.; Harvey, A.; Grattan, K.; Adamo, K.B. Physical activity promotion in the preschool years: A critical period to intervene. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 1326–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, S.G.; Ward, D.S.; Senso, M. Effects of child care policy and environment on physical activity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowda, M.; Brown, W.H.; McIver, K.L.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; O’Neill, J.R.; Addy, C.L.; Pate, R.R. Policies and characteristics of the preschool environment and physical activity of young children. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e261–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, Y.G.; Cliff, D.P.; Okely, A.D. Childcare Educators’ Perceptions of and Solutions to Reducing Sitting Time in Young Children: A Qualitative Study. Early Child. Educ. J. 2018, 46, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.; Dyment, J.E. Factors that limit and enable preschool-aged children’s physical activity on child care centre playgrounds. J. Early Child. Res. 2013, 11, 203–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevimli-Celik, S.E.; Johnson, J. I Need to Move and So Do the Children. Int. Educ. Stud. 2013, 6, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, J.K.; Hales, D.P.; Tate, D.F.; Rubin, D.A.; Benjamin, S.E.; Ward, D.S. The Childcare Environment and Children’s Physical Activity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2008, 34, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.J.; van Kann, D.H.H.; Stafleu, A.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Thijs, C.; de Vries, N.K. Interaction Between Physical Environment, Social Environment, and Child Characteristics in Determining Physical Activity at Child Care. Health Psychol. 2011, 30, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P. Teachers as role models for physical activity: Are preschool children more active when their teachers are active? Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 2020, 26, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunter, K.B.; Rice, K.R.; Ward, D.S.; Trost, S.G. Factors associated with physical activity in children attending family child care homes. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderloo, L.M.; Tucker, P.; Johnson, A.M.; van Zandvoort, M.M.; Burke, S.M.; Irwin, J.D. The influence of centre-based childcare on preschoolers’ physical activity levels: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.H.; Googe, H.S.; McIver, K.L.; Rathel, J.M. Effects of Teacher-Encouraged Physical Activity on Preschool Playgrounds. J. Early Interv. 2009, 31, 126–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Thornton, A.; Lester, L.; Schipperijn, J.; Trapp, G.; Boruff, B.; Ng, M.; Wenden, E.; Christian, H. Nature Play and Fundamental Movement Skills Training Programs Improve Childcare Educator Supportive Physical Activity Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijns, B.A.; Johnson, A.M.; Irwin, J.D.; Burke, S.M.; Driediger, M.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Tucker, P. Training may enhance early childhood educators’ self-efficacy to lead physical activity in childcare. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassani, K.; Buckler, E.J.; McConnell-Nzunga, J.; Fakih, S.; Scarr, J.; Mâsse, L.C.; Naylor, P.-J. Implementing Appetite to Play at scale in British Columbia: Evaluation of a Capacity-Building Intervention to Promote Physical Activity in the Early Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruijns, B.A.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Adamo, K.B.; Burke, S.M.; Carson, V.; Heydon, R.; Irwin, J.D.; Naylor, P.-J.; Timmons, B.W.; et al. Change in pre- and in-service early childhood educators’ knowledge, self-efficacy, and intentions following an e-learning course in physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Blanger, M.; Donovan, D.; Vatanparast, H.; Muhajarine, N.; Engler-Stringer, R.; Leis, A.; Humbert, M.L.; Carrier, N. Association between childcare educators’ practices and preschoolers’ physical activity and dietary intake: A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossdal, T.S.; Kippe, K.; Handegård, B.H.; Lagestad, P. “Oh oobe doo, I wanna be like you” associations between physical activity of preschool staff and preschool children. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.A.; Russ, L.; Vazou, S.; Goh, T.L.; Erwin, H. Integrating movement in academic classrooms: Understanding, applying and advancing the knowledge base. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Smith, A.; Quarmby, T.; Archbold, V.; Corrigan, N.; Resaland, G.K.; Bartholomew, J.; Singh, A.; Tjomsland, H.; Sherar, L.; Chalkley, A.; et al. Using a multi-stakeholder experience-based design process to co-develop the Creating Active Schools Framework. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, J.A.; Engelberg, J.K.; Cain, K.L.; Conway, T.L.; Geremia, C.; Bonilla, E.; Kerner, J.; Sallis, J.F. Contextual factors related to implementation of classroom physical activity breaks. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazou, S.; Skrade, M. Teachers’ Reflections From Integrating Physical Activity in the Academic Classroom. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2014, 85, A38. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, J.A.; Mignano, A.M.; Norman, G.J.; McKenzie, T.L.; Kerr, J.; Arredondo, E.M.; Madanat, H.; Cain, K.L.; Elder, J.P.; Saelens, B.E.; et al. Socioeconomic Disparities in Elementary School Practices and Children’s Physical Activity during School. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28 (Suppl. S3), S47–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowda, M.; Pate, R.R.; Trost, S.G.; Almeida, M.J.C.A.; Sirard, J.R. Influences of Preschool Policies and Practices On Children’s Physical Activity. J. Community Health 2004, 29, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonge, K.L.; Jones, R.A.; Okely, A.D. Correlates of children’s objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in early childhood education and care services: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2015, 89, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesketh, K.R.; O’Malley, C.; Paes, V.M.; Moore, H.; Summerbell, C.; Ong, K.K.; Lakshman, R.; van Sluijs, E.M.F. Determinants of Change in Physical Activity in Children 0-6 years of Age: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Literature. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1349–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. J. Black Psychol. 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, M.P.; Maitland, C.; Mackintosh, K.A.; Rosenberg, M.; Griffiths, L.J.; Fry, R.; Stratton, G. Clusters of Activity-Related Social and Physical Home Environmental Factors and Their Association With Children’s Home-Based Physical Activity and Sitting. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2023, 35, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orendorff, K.; Webster, C.A.; Mindrila, D.; Cunningham, K.M.W.; Doutis, P.; Dauenhauer, B.; Stodden, D.F. Social-ecological and biographical perspectives of principals’ involvement in comprehensive school physical activity programs: A person-centered analysis. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2022, 29, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, A.; Adams, E.; Trost, S.; Cross, D.; Schipperijn, J.; McLaughlin, M.; Thornton, A.; Trapp, G.; Lester, L.; George, P.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of the Play Active policy intervention and implementation support in early childhood education and care: A pragmatic cluster randomised trial protocol. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.S.; Morris, E.; McWilliams, C.; Vaughn, A.; Erinosho, T.; Mazzucca, S.; Hanson, P.; Ammerman, A.; Neelon, S.; Sommers, J.; et al. Go NAP SACC: Nutrition and Physical Activity Self-Assessment for Child Care, 2nd ed.; Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention and Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: www.gonapsacc.org (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- Ward, D.S.; Mazzucca, S.; McWilliams, C.; Hales, D. Use of the Environment and Policy Evaluation and Observation as a Self-Report Instrument (EPAO-SR) to measure nutrition and physical activity environments in child care settings: Validity and reliability evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maitland, C.; Lester, L.; Trost, S.G.; Rosenberg, M.; Schipperijn, J.; Trapp, G.; Bai, P.; Christian, H. The Influence of the Early Childhood Education and Care Environment on Young Children’s Physical Activity: Development and Reliability of the PLAYCE Study Environmental Audit and Educator Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.; Hales, D.; Haverly, K.; Marks, J.; Benjamin, S.; Ball, S.; Trost, S. An Instrument to Assess the Obesogenic Environment of Child Care Centers. Am. J. Health Behav. 2008, 32, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakk, Z.; Tekle, F.B.; Vermunt, J.K. Estimating the Association between Latent Class Membership and External Variables Using Bias-adjusted Three-step Approaches. Sociol. Methodol. 2013, 43, 272–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Innovations. Latent GOLD; Statistical Innovations: Belmont, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, P.; Vanderloo, L.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Burke, S.M.; Irwin, J.D.; Gaston, A.; Driediger, M.; Timmons, B.W. Impact of the Supporting Physical Activity in the Childcare Environment (SPACE) intervention on preschoolers’ physical activity levels and sedentary time: A single-blind cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M. From Theory to Intervention: Mapping Theoretically Derived Behavioural Determinants to Behaviour Change Techniques. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenden, E.J.; Virgara, R.; Pearce, N.; Budgeon, C.; Christian, H.E. Movement behavior policies in the early childhood education and care setting: An international scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1077977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenden, E.J.; Pearce, N.; George, P.; Christian, H.E. Educators’ Barriers and Facilitators to Physical Activity Policy Implementation in the Childcare Setting: Qualitative Findings From the Play Active Project. Am. J. Health Promot. 2022, 36, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (n = 568) | 33.0 | 15.0 |

| Length of time worked in childcare sector in months (n = 566) | 72.0 | 97.0 |

| Length of time worked in current service in months (n = 567) | 19.0 | 42.0 |

| Usual hours per week working in room in service (n = 559) | 37.0 | 9.5 |

| n | % | |

| Gender—Female (n = 572) | 565 | 98.8 |

| Highest schooling completed (n = 570) | ||

| Year 12 or lower | 123 | 21.6 |

| Trade or diploma | 291 | 51.1 |

| University degree | 156 | 27.4 |

| Works with (n = 573) | 390 | 68.1 |

| Only toddlers (aged 1–2 years) | 215 | 41.9 |

| Only kindergarten children (aged 3–5 years) | 148 | 28.8 |

| Children aged 1–5 | 150 | 29.2 |

| Received physical activity professional development in the last two years 1 (n = 518) | 363 | 70.1 |

| Meeting best practice guidelines for provision of physical activity | ||

| Total physical activity (n = 532) | 367 | 69.0 |

| Energetic play (n = 525) | 432 | 82.3 |

| Total physical activity and energetic play (n = 525) | 322 | 61.3 |

| Meeting Total Physical Activity | Meeting Energetic Play | Meeting Both Guidelines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Β (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| 1. Positive behaviour managers | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.1) | 1.7 (0.9, 3.0) | 0.6 (0.0, 1.3) | 1.9 (1.0, 3.7) | 0.7 (0.1, 1.2) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.4) |

| 2. Frequent planners | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.1) | 1.6 (0.9, 3.0) | 0.7 (0.0, 1.4) | 1.9 (1.0, 4.0) | 0.7 (0.1, 1.3) | 1.9 (1.1, 3.6) |

| 3. Need support | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 4. Role models | 1.2 (0.4, 1.9) | 3.2 (1.5, 7.0) | 0.9 (0.0, 1.7) | 2.4 (1.0, 5.5) | 1.1 (0.4, 1.8) | 3.0 (1.5, 6.1) |

| 5. Infrequent use of practices | 0.3 (−0.4, 1.1) | 1.4 (0.7, 2.9) | 1.5 (0.3, 2.8) | 4.6 (1.3, 16.2) | 0.6 (−0.1, 1.4) | 1.9 (0.9, 4.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adams, E.K.; Nathan, A.; George, P.; Trost, S.G.; Schipperijn, J.; Christian, H. Physical Activity-Related Practices and Psychosocial Factors of Childcare Educators: A Latent Profile Analysis. Children 2024, 11, 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040390

Adams EK, Nathan A, George P, Trost SG, Schipperijn J, Christian H. Physical Activity-Related Practices and Psychosocial Factors of Childcare Educators: A Latent Profile Analysis. Children. 2024; 11(4):390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040390

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdams, Emma K., Andrea Nathan, Phoebe George, Stewart G. Trost, Jasper Schipperijn, and Hayley Christian. 2024. "Physical Activity-Related Practices and Psychosocial Factors of Childcare Educators: A Latent Profile Analysis" Children 11, no. 4: 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040390

APA StyleAdams, E. K., Nathan, A., George, P., Trost, S. G., Schipperijn, J., & Christian, H. (2024). Physical Activity-Related Practices and Psychosocial Factors of Childcare Educators: A Latent Profile Analysis. Children, 11(4), 390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040390