Mapping Psychosocial Challenges, Mental Health Difficulties, and MHPSS Services for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children in Greece: Insights from Service Providers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. The Survey

2.4. Quantitative Analyses

2.5. Qualitative Analyses

3. Results

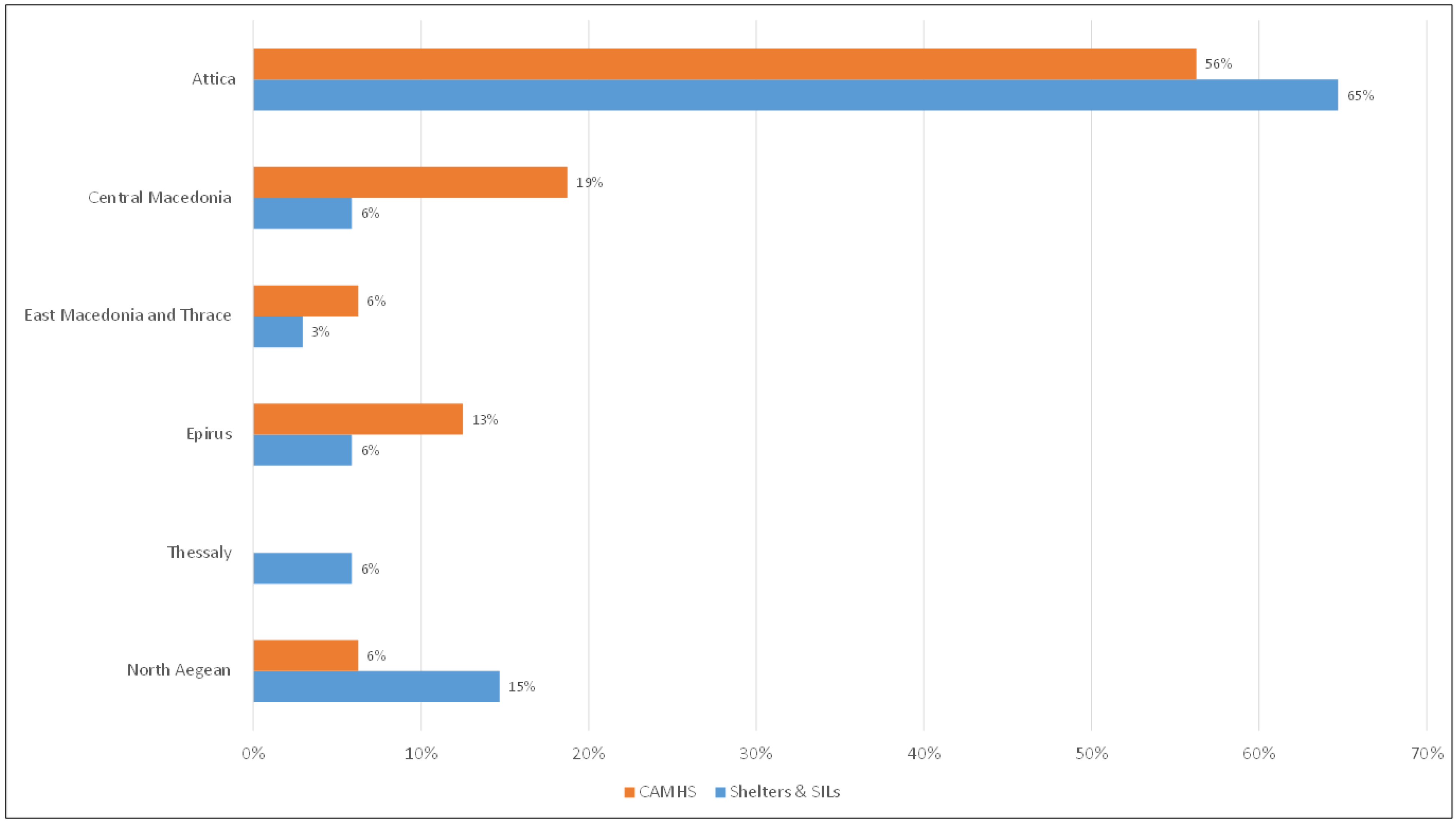

3.1. Profile of UASC and Field Workers Supporting Them

3.1.1. Profile of UASC Living in Long-Term Accommodation Facilities

3.1.2. Profile of Field Workers Providing Psychosocial Support to UASC

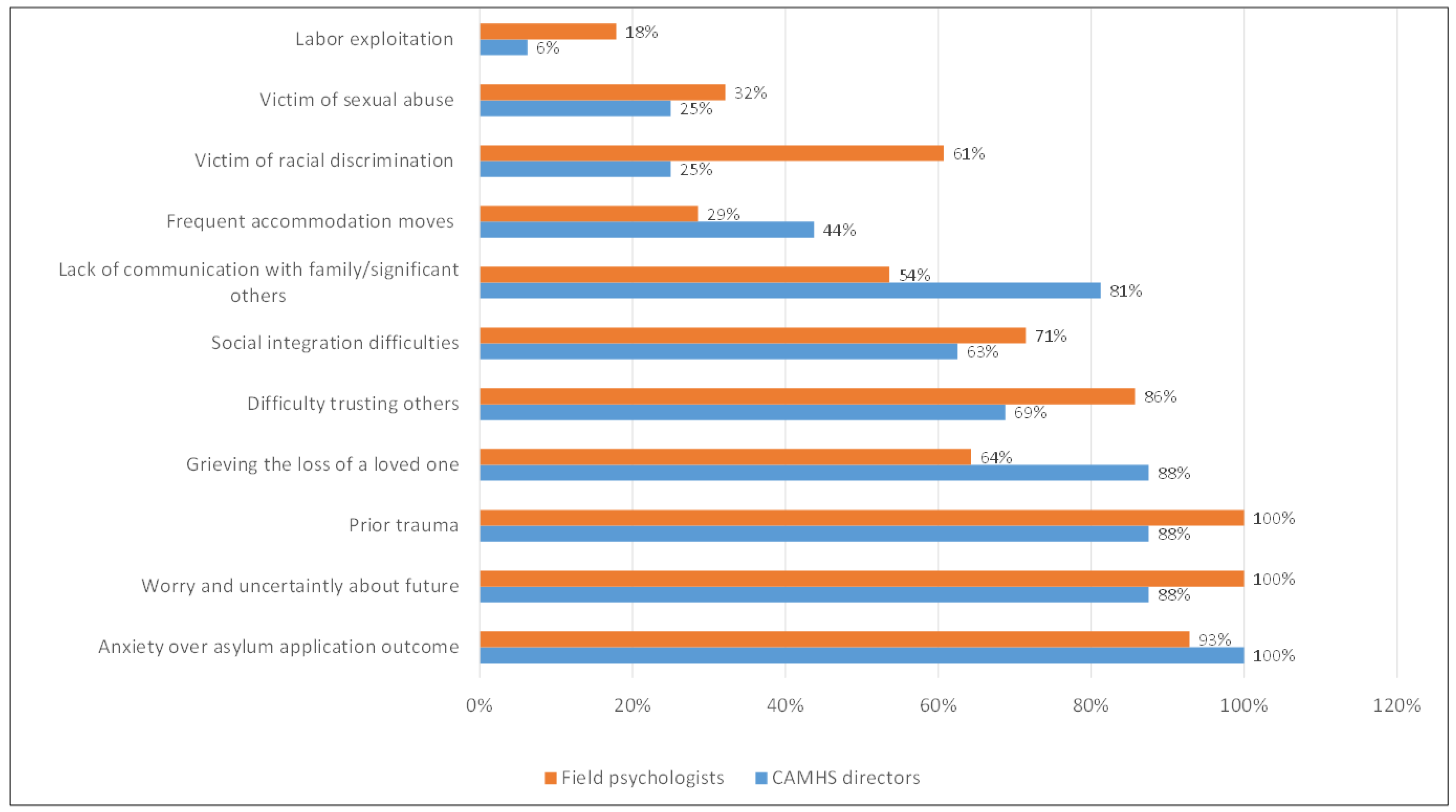

3.2. Psychosocial and Mental Health Needs of UASC

3.2.1. UASC’s Psychosocial Challenges as Perceived by Field Psychologists and CAMHS Directors

3.2.2. UASC’s Psychosocial Needs as Perceived by Field Psychologists

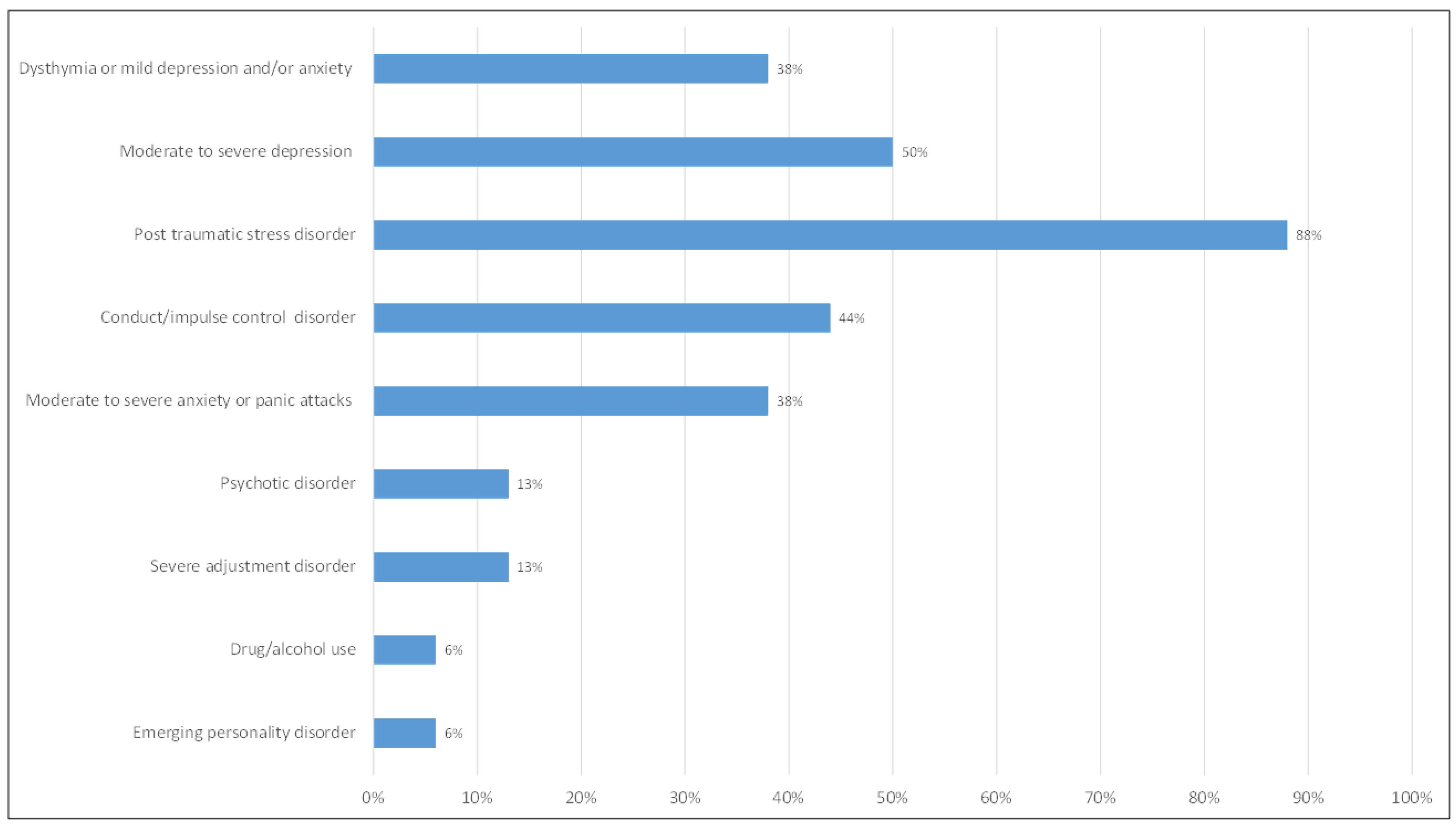

3.2.3. UASC’s Mental Health Needs as Perceived by Field Psychologists

3.3. MHPSS Services Provided to UASC

3.3.1. Range of Psychosocial Services Provided in Accommodation Settings

3.3.2. Range of Mental Health Services Provided by CAMHS

3.4. Challenges to Providing Effective MHPSS Services to UASC

3.4.1. Referral and Collaboration Issues Among Field and CAMHS Personnel

3.4.2. Challenges Regarding Provision of Psychosocial Support in Shelters

3.4.3. Perceived Work Culture in Shelters

3.5. Recommendations by Survey Participants

3.5.1. Team Issues

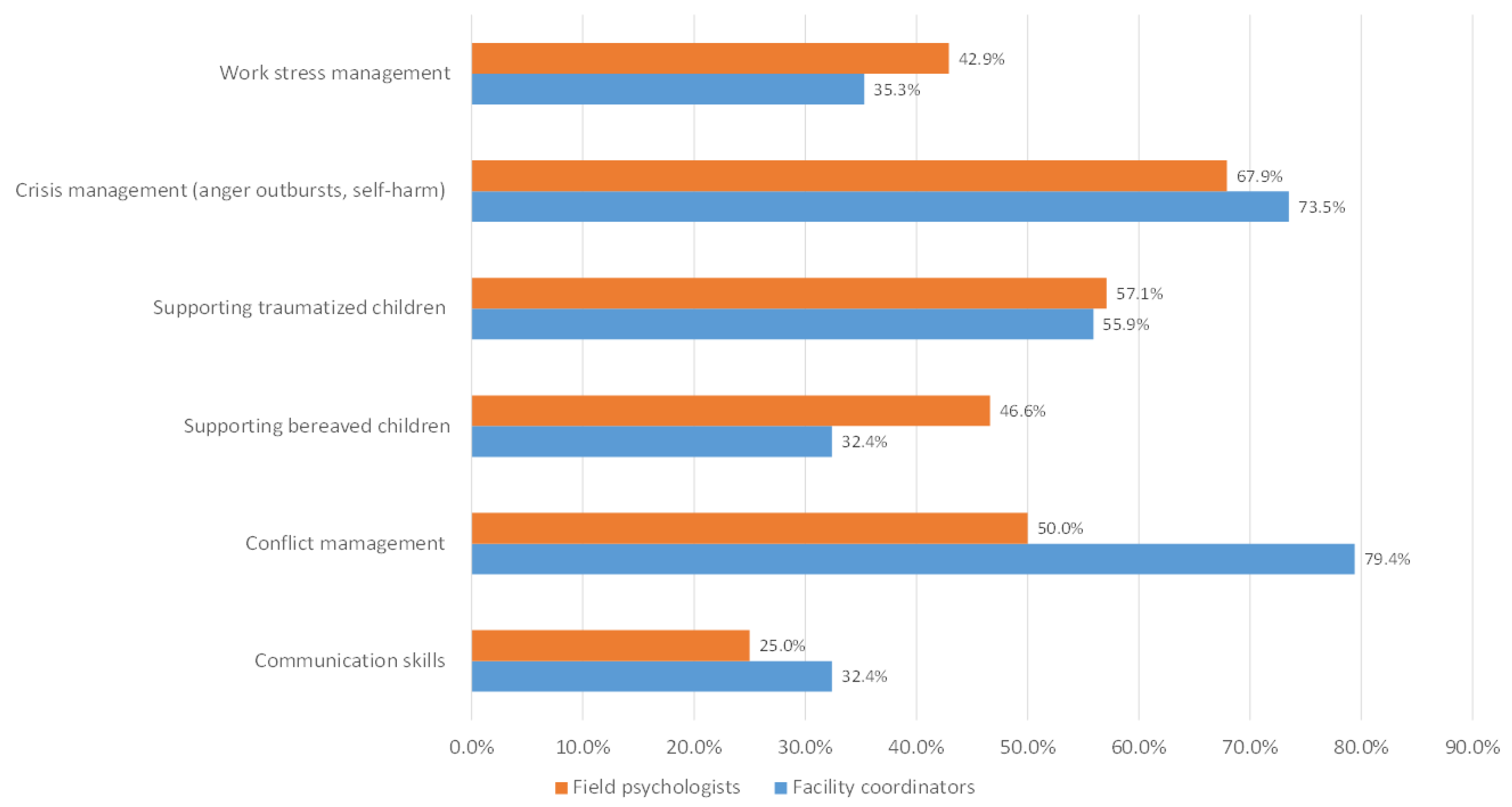

3.5.2. Ongoing Training and Staff Supervision

3.5.3. Improvement of Referral Pathways

4. Discussion

4.1. Perceived UASC’s Psychosocial and Mental Health Needs

4.2. The Nature of Services, Gaps, Obstacles, and Good Practices in Supporting UASC

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weber, H. Politics of ‘Leaving No One Behind’: Contesting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals Agenda. Globalizations 2017, 14, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, E.; Allsopp, J. Youth Migration and the Politics of Wellbeing; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fili, A.; Xythali, V. The Continuum of Neglect: Unaccompanied Minors in Greece. Soc. Work. Soc. 2017, 15, 1–14. Available online: https://ejournals.bib.uni-wuppertal.de/index.php/sws/article/view/521 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Bamford, J.; Fletcher, M.; Leavey, G. Mental Health Outcomes of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors: A Rapid Review of Recent Research. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2021, 23, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.; Reed, R.V.; Panter-Brick, C.; Stein, A. Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high-income countries: Risk and protective factors. Lancet 2012, 379, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopoulou, I.; Mourloukou, L.; Efstathiou, V.; Douzenis, A.; Ferentinos, P. Mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece living “in limbo”. Psychiatriki 2022, 33, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodes, M.; Vostanis, P. Practitioner Review: Mental health problems of refugee children and adolescents and their management. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, S.L.; Kia-Keating, M.; Knight, W.G.; Geltman, P.; Ellis, H.; Kinzie, J.D.; Keane, T.; Saxe, G.N. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.; Meyer DeMott, M.A.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Heir, T. The impact of the asylum process on mental health: A longitudinal study of unaccompanied refugee minors in Norway. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digidiki, V.; Bhabha, J. Emergency Within an Emergency: The Growing Epidemic of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse of Migrant Children in Greece. 2017. Available online: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/emergency-within-emergency-growing-epidemic-sexual-exploitation-and-abuse-migrant-children/ (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Digidiki, V.; Bhabha, J. Sexual abuse and exploitation of unaccompanied migrant children in Greece: Identifying risk factors and gaps in services during the European migration crisis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantou, E.; Theodoropoulou, A. Children Cast Adrift: The Exclusion and Exploitation of Unaccompanied Minors in Greece, Spain and Italy—Comperative Report. The Rosa Luxembourg Stifung Office in Greece. 2019. Available online: https://refugeeobservatory.aegean.gr/en/children-cast-adrift-exclusion-and-exploitation-unaccompanied-minors-uams-greece-%CE%B2y-e-sarantou?language_content_entity=en (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Nikolaidis, G.; Ntinapogias, A.; Stavrou, M. Executive Summary—Rapid Assessment of Mental Health, Psychosocial Needs and Services for Unaccompanied Children in Greece|ChildHub—Child Protection Hub. Institute of Child Health, Department of Mental Health and Social Welfare. 2017. Available online: https://childhub.org/en/child-protection-online-library/executive-summary-rapid-assessment-mental-health-psychosocial-needs?language=el (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Greek Law No. 4554 of 18 July 2018 on the Regulatory Framework for the Guardianship of Unaccompanied Minors | European Website on Integration. Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/greek-law-no-4554-18-july-2018-regulatory-framework-guardianship-unaccompanied_en (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Greece: Protection of Unaccompanied Minors|European Website on Integration. Available online: https://migrant-integration.ec.europa.eu/library-document/greece-protection-unaccompanied-minors_en (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Koimtzoglou, I.L.-I. Greece—Changes to Documentation and Conditions for Intra-Corporate Transfers and for Certain Visas and Residence Permits. Lexology. 2019. Available online: https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=efe4dabd-f393-49a3-87f2-bd2f51bd28a4 (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- EKKA-National Center for Social Solidarity. Situation Update on Unacompanied Minors in Greece in March 2020. Available online: https://www.ekka.org.gr/index.php/el/rolos-skopos-tou-ekka/statistika (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Baca, M.J.; Fayyad, K.; Marini, A.; Weissbecker, I. The development of a comprehensive mapping service for mental health and psychosocial support in Jordan. Intervention 2012, 10, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R.; Poudyal, B.; Streel, E.; Bahgat, F.; Tol, W.; Ventevogel, P. Who is Where, When, doing What: Mapping services for mental health and psychosocial support in emergencies. Intervention 2012, 10, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Chatman, J.A.; Caldwell, D.F. People and Organizational Culture: A Profile Comparison Approach to Assessing Person-Organization Fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popping, R. Analyzing Open-ended Questions by Means of Text Analysis Procedures. Bull. Sociol. Methodol./Bull. Méthodol. Sociol. 2015, 128, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, A.; Kallinikaki, T. Meeting the needs of unaccompanied children in Greece. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 63, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.K.; Fjermestad, K.W.; Granly, L.; Wilhelmsen, N.H. Stressful life experiences and mental health problems among unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Clin. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 20, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.R.F.; Büter, K.P.; Rosner, R.; Unterhitzenberger, J. Mental health and associated stress factors in accompanied and unaccompanied refugee minors resettled in Germany: A cross-sectional study. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2019, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kien, C.; Sommer, I.; Faustmann, A.; Gibson, L.; Schneider, M.; Krczal, E.; Jank, R.; Klerings, I.; Szelag, M.; Kerschner, B.; et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in young refugees and asylum seekers in European Countries: A systematic review. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 1295–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramel, B.; Täljemark, J.; Lindgren, A.; Johansson, B.A. Overrepresentation of unaccompanied refugee minors in inpatient psychiatric care. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kringos, D.S.; Boerma, W.G.; Bourgueil, Y.; Cartier, T.; Hasvold, T.; Hutchinson, A.; Lember, M.; Oleszczyk, M.; Pavlic, D.R.; Svab, I.; et al. The european primary care monitor: Structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Fam. Pract. 2010, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, T.M.; Eurelings-Bontekoe, E.; Spinhoven, P. Course and predictors of mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in the Netherlands: One year follow-up. Soc. Sci. Med. 2007, 64, 1204–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Cao, E.; Kramer, T.; Hodes, M. Psychological distress and mental health service contact of unaccompanied asylum-seeking children. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Werthern, M.; Grigorakis, G.; Vizard, E. The mental health and wellbeing of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URMs). Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 98, 104146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelliott, J. Unaccompanied Children in Limbo: The Causes and Consequences of Uncertain Legal Status. Int. J. Refug. Law 2022, 34, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jore, T.; Oppedal, B.; Biele, G. Social anxiety among unaccompanied minor refugees in Norway.The association with pre-migration trauma and post-migration acculturation related factors. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 136, 110175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey 1. Facility Coordinators | Survey 2. Field Psychologists | Survey 3. CAMHS Directors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | WHO? | Facility personnel | Field psychologists | Mental health professionals |

| 2. | WHERE? | Geographical location | Geographical location (Similar to that of facility coordinators) | Geographical location |

| 3. | WHAT? | UASC’s psychosocial needs and living conditions | UASC’s psychosocial, mental health needs, and the nature of psychosocial support | UASC’s mental health symptoms/disorders and nature of service provision |

| 4. | WHEN? | Referral procedures and collaboration with CAMHS | Referral procedures and collaboration with CAMHS | Collaboration with the personnel of facility accommodation |

| 5. | WHICH? | Resources, gaps, obstacles, work culture, and recommendations | Resources, gaps, obstacles, work culture, and recommendations | Resources, gaps, obstacles, and recommendations |

| Referred to CAMHS | Voluntary Admission | Compulsory Admission | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of symptoms | N (%) | N (% within type of symptoms) | N (% within type of symptoms) | N (% within type of symptoms) |

| Psychotic symptoms | 28 (6) | 28 (100) | 8 (28.6) | 7 (25) |

| PTSD symptoms | 71 (15.1) | 49 (69) | 5 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Suicide attempt | 14 (3) | 14 (100) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) |

| Depression symptoms | 83 (17.7) | 49 (59) | 5 (6) | 3 (3.7) |

| Anxiety/Panic attacks | 45 (9.6) | 28 (62.2) | 4 (8.9) | 1 (2.2) |

| Self-harm behavior | 61 (13) | 35 (57.4) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (4.9) |

| Violent behavior | 79 (16.8) | 34 (43%) | 3 (3.8) | 3 (3.8) |

| Alcohol/Substance use | 87 (18.6) | 33 (37.9) | 3 (3.4) | 3 (3.4) |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TOTAL | 469 (100) | 271 (57.8%) a | 44 (16.2%) b | 31 (11.4%) b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giannopoulou, I.; Papanastasatos, G.; Vathakou, E.; Bellali, T.; Tselepi, K.; Papadopoulos, P.; Kazakou, M.; Papadatou, D. Mapping Psychosocial Challenges, Mental Health Difficulties, and MHPSS Services for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children in Greece: Insights from Service Providers. Children 2024, 11, 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121413

Giannopoulou I, Papanastasatos G, Vathakou E, Bellali T, Tselepi K, Papadopoulos P, Kazakou M, Papadatou D. Mapping Psychosocial Challenges, Mental Health Difficulties, and MHPSS Services for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children in Greece: Insights from Service Providers. Children. 2024; 11(12):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121413

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiannopoulou, Ioanna, Gerasimos Papanastasatos, Eugenia Vathakou, Thalia Bellali, Konstantia Tselepi, Paraskevas Papadopoulos, Myrsini Kazakou, and Danai Papadatou. 2024. "Mapping Psychosocial Challenges, Mental Health Difficulties, and MHPSS Services for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children in Greece: Insights from Service Providers" Children 11, no. 12: 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121413

APA StyleGiannopoulou, I., Papanastasatos, G., Vathakou, E., Bellali, T., Tselepi, K., Papadopoulos, P., Kazakou, M., & Papadatou, D. (2024). Mapping Psychosocial Challenges, Mental Health Difficulties, and MHPSS Services for Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Children in Greece: Insights from Service Providers. Children, 11(12), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11121413