1. Introduction

Kangaroo Care (KC), a method of skin-to-skin contact between parent and infant, has gained considerable attention for its profound benefits on preterm infants in the NICU. With over four decades of empirical evidence, KC has proven effective in enhancing parent-infant bonding, promoting weight gain, stabilizing respiratory and cardiac functions, supporting neurological development, and reducing stress levels in both mother and infant [

1,

2,

3,

4]. A recent review of 31 trials with 15,559 infants showed that compared to conventional care, KC reduces mortality risks during birth hospitalization and decreases rates of severe infection. The decrease in infant mortality with KC was observed regardless of gestational age or enrollment weight [

5]. However, the application of KC is limited for infants who require complex medical equipment, such as intravenous lines, nasogastric tubes, and respiratory support. Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs) are categorized into different levels based on the complexity of care they provide, with Level IV being the highest. Level III and IV NICUs offer the most advanced care for premature and sick newborns, equipped to handle the most complex and high-risk situations with state-of-the-art technology and an interdisciplinary team. In the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), nurses play a crucial role in providing support to parents, especially concerning Kangaroo Care (KC). This skin-to-skin practice is not only critical for the infant’s physiological stabilization and growth but also for nurturing the maternal bond which is crucial in a high-tech, high-intensity care environment [

6,

7]. Recent literature underscores the urgent need for ergonomically designed, safe support products tailored for the unique challenges of the high acuity (Level III and Level IV) NICU environment [

8]. These products should aim to facilitate a comfortable experience for both the parent and the critically ill infant, while securely managing multiple medical lines without compromising parental comfort. At present, many NICUs resort to makeshift solutions like taping lines and tubes to parents or chairs, coupled with blanket coverage for warmth. These ad hoc methods raise significant safety concerns, including the risk of accidental falls, medical equipment dislodgement, and unplanned extubation. Moreover, the lack of standardization exacerbates the inconsistency in securing medical devices effectively.

Additional challenges in the widespread adoption of KC include limited awareness of its benefits, time constraints, staff and parent anxiety, inadequate training, and a dearth of specialized KC support devices [

9,

10]. Products currently on the market include The Zaky Zak

® Joeyband™ and The Moby Wrap

®. These examples resemble tube tops or baby-carrying wraps which may help facilitate KC with babies; however, they are not specifically designed for high-acuity infants with multiple lines and tubes that need to be managed while performing KC. Clinician surveys have identified key design features essential for a successful KC device, such as secure infant holding mechanisms, washability, and easy access to medical procedures [

11].

To address these multifaceted needs, we crafted survey questions based on barriers faced by both clinicians and parents while performing KC in a high acuity setting and employed design thinking methodology, incorporating invaluable insights from NICU clinicians and parents, to develop the Kangarobe™.

This feasibility study aimed to evaluate the utility and potential benefits of the Kangarobe™ in high acuity settings with babies who have multiple lines and tubes, in comparison to standard practice, as described above. Specifically, the study focuses on evaluating the duration of transfer for KC, ease of use, comfort levels for the parent-infant dyad, security of support devices, and procedural accessibility.

2. Methods

The inventors applied Design Thinking (DT), also known as ‘human-centered design’, in developing the Kangarobe™. (

Table 1). This approach prioritizes addressing unmet human needs as the primary objective, with its framework specifically structured to achieve this goal [

12,

13]. The design-thinking framework progresses through three main stages: (1) understanding, (2) exploring, and (3) materializing. These stages encompass six phases: empathize, define, ideate, prototype, test, and implement [

13].

2.1. Device Features and Materials

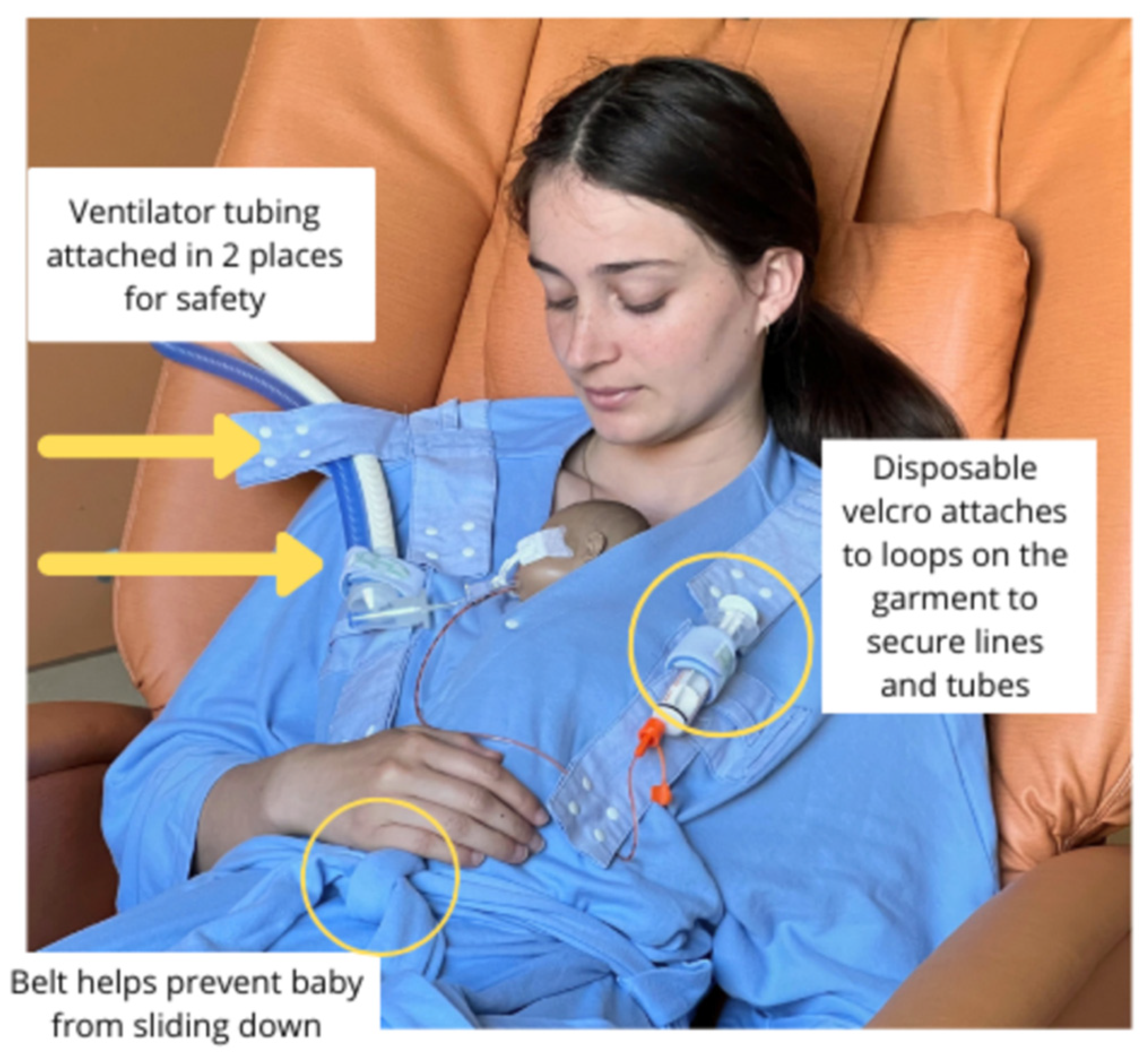

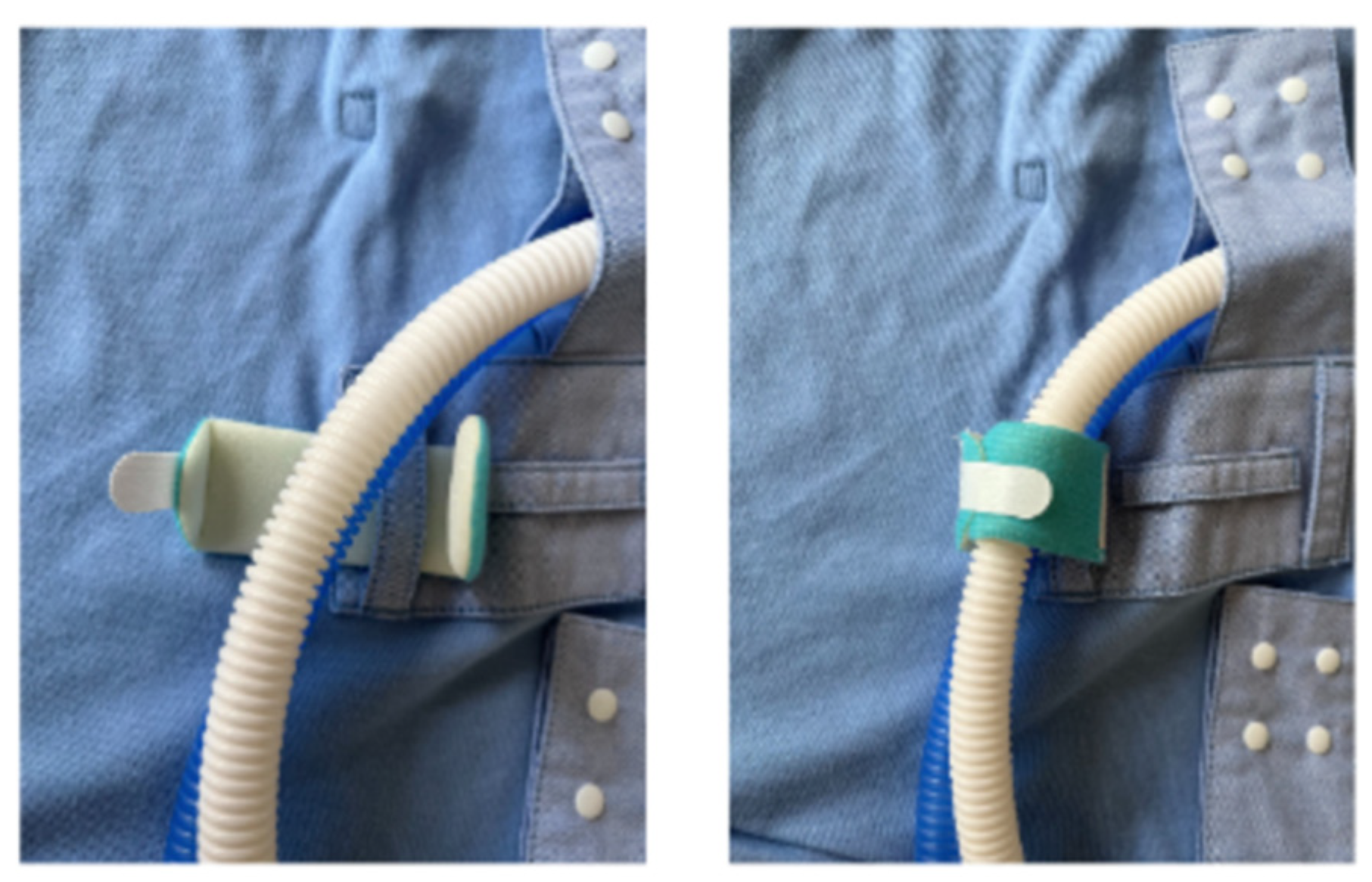

The Kangarobe™ is a soft, full-coverage garment that functions akin to a robe, designed for parents to safely engage in KC with their infant in the NICU [

Figure 1]. Crafted from a machine-washable blend of 60% cotton and 40% polyester, the garment offers a versatile one-size-fits-most design. For enhanced positional support, a strategically placed belt can be placed beneath the baby. Engineered for adaptability, the Kangarobe™ features an array of snap fasteners and loops strategically located across the shoulders and chest. Loops are used with disposable foam wraps or bracelets with single-use Velcro

®, allowing for the secure placement of several types of respiratory, feeding, and vascular tubing. The garment is designed to support various respiratory devices, including low and high-flow nasal cannulas, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) systems, and ventilator tubing. Opting for disposable Velcro

® closures over permanent ones mitigates the risk of unsanitary debris accumulation in the permanent Velcro

®, thereby ensuring long-term effectiveness.

Among its patented innovations, the Kangarobe™ incorporates multiple snaps and attachment loops [

Figure 2], as well as a vertical access window [

Figure 3]. This unique feature grants clinicians unobtrusive access to the infant for medical evaluations and interventions, all while maintaining the integrity of the KC experience. Additionally, adjustable snaps on the neckline ensure that parents remain covered during medical procedures on the baby, further enhancing the garment’s utility and comfort.

2.2. User Survey Methods

The Kangarobe™ garment was evaluated with 25 parent-infant pairs from 1 September 2021 to 31 August 2023, in the level IV NICU at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford. The study received approval from the Stanford University Institutional Review Board, protocol ID 60251. Participants were eligible if the parent had experience holding skin-to-skin at least three times and the infant was dependent on a respiratory support device. Informed consent was obtained from study participants. Parents and nurses were provided instructions by a research assistant on how to put on and use a freshly laundered Kangarobe™. Additionally, both parents and nurses were provided access to an instructional video available in both English and Spanish. The data collected included the start and end times of KC, and the number of staff engaged in set up and return of infants. For the last seven patients, temperature prior to and after KC was recorded.

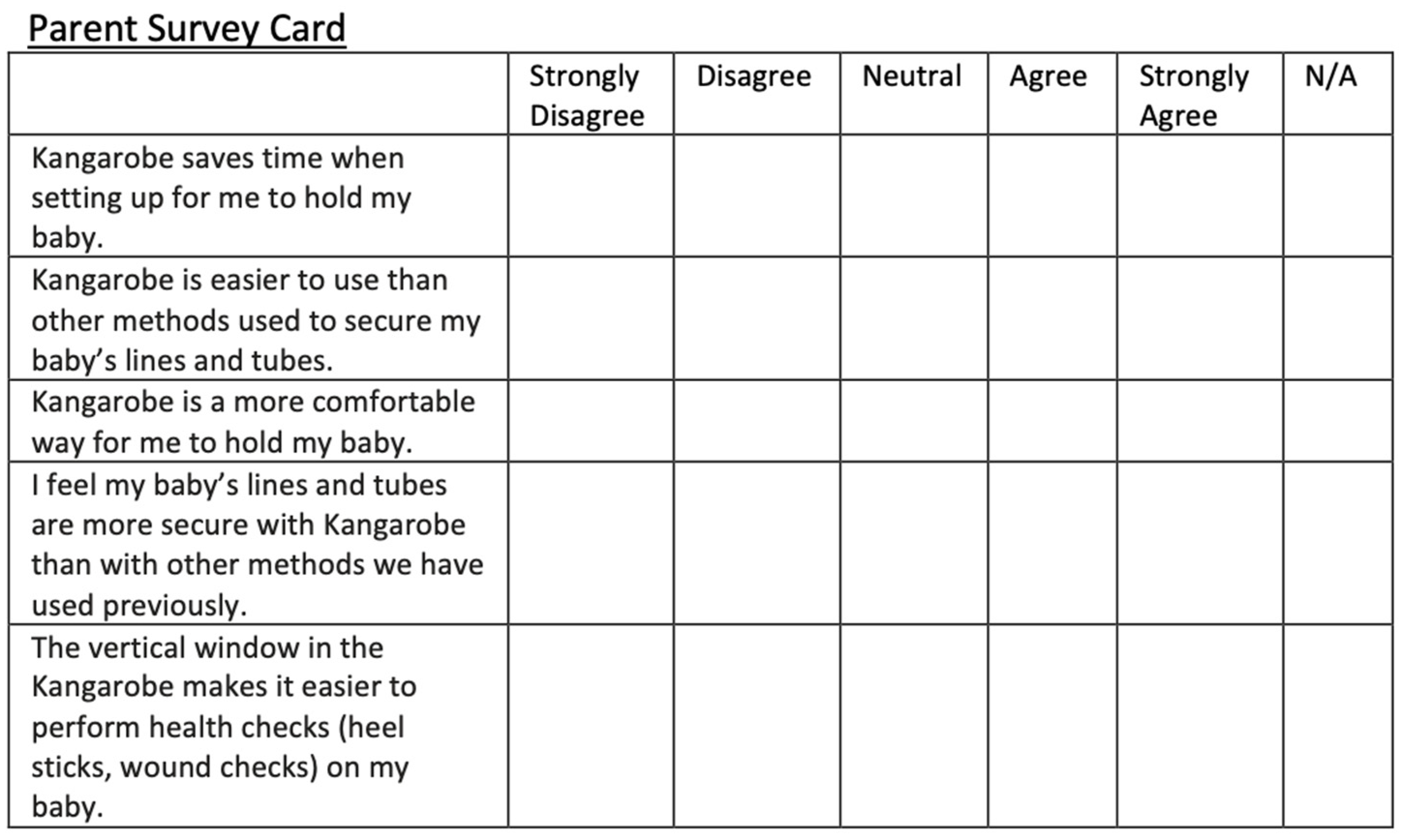

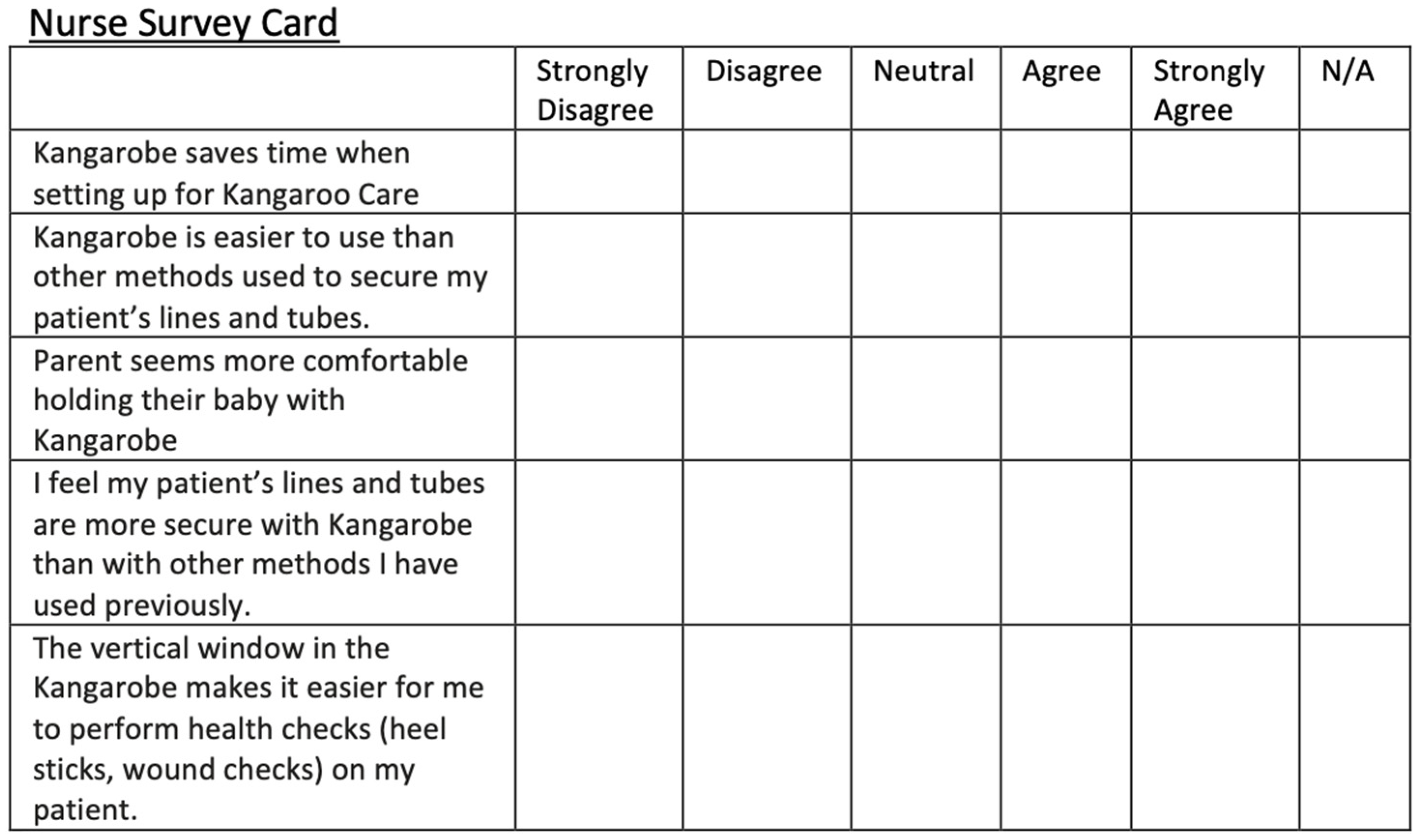

We developed a qualitative survey for parents and nurses ensuring the questions would capture the experiences, perceptions, and insights of the participants. Questions were developed by defining our objectives (understanding ease of use, comfort, and safety for babies connected to multiple lines and tubes) and pilot testing them to be sure they were clear and provided us with valuable data. After KC using the Kangarobe™ (Gold Health, LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA), both parents and nurses were surveyed using a 5-point Likert scale to collect responses regarding time efficiency, safety, comfort, ease of set up/use, and procedure access. Participants could respond with the following: “strongly agree”, “agree”, “neutral”, “disagree”, or “strongly disagree”. Nurses and parents were given similar surveys. (

Figure 4) Parents and nurses were also given the opportunity to provide verbal or written feedback about their experiences with the Kangarobe™ (Gold Health, LLC, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Design Feedback Results

Comments in

Table 2 and

Table 3 were integral to the iterative design process for the Kangarobe. This feedback was given throughout our design process.

3.2. User Survey Results

The pilot study of the Kangarobe™ included a convenience sample of 23 mother-baby, and 2 fathers-baby dyads, and reflected our NICU demographics with multiple ethnicities and approximately 50% with public insurance. In this human pilot study, the infants had an average corrected gestational age of 33 weeks (ranging from 25 to 42 weeks) and a mean weight of 1.145 kg (ranging from 0.64 kg to 3.56 kg). Out of 25 infants in the study, 19 were on CPAP and 6 were on HFNC. The Kangarobe™ garment is compatible for use with intubated babies, but no intubated participants were recruited in this study. Of the total participants, all babies had gastric tubes, and 6 had IV lines, including three PICC and three peripheral intravenous (PIV) lines.

Transferring infants to parents wearing the Kangarobe™ and back to their bed took an average of 4.2 min and 4 min, respectively. Parents held using the Kangarobe™ for 171 min per instance on average, with 308 min being the longest hold and 20 min being the shortest hold. For comparison, based on quality improvement data, the median duration of KC by parents in the Stanford NICU in 2022 was 75 min per instance. There were no safety events reported in this study with the use of the Kangarobe™. For the last seven participants, the baby’s axillary temperature was taken prior to and after KC. The temperature difference on average was an increase of 0.1C, excluding one outlier having a 2.3 °C temperature decrease (from 38.6 prior to 36.3 after).

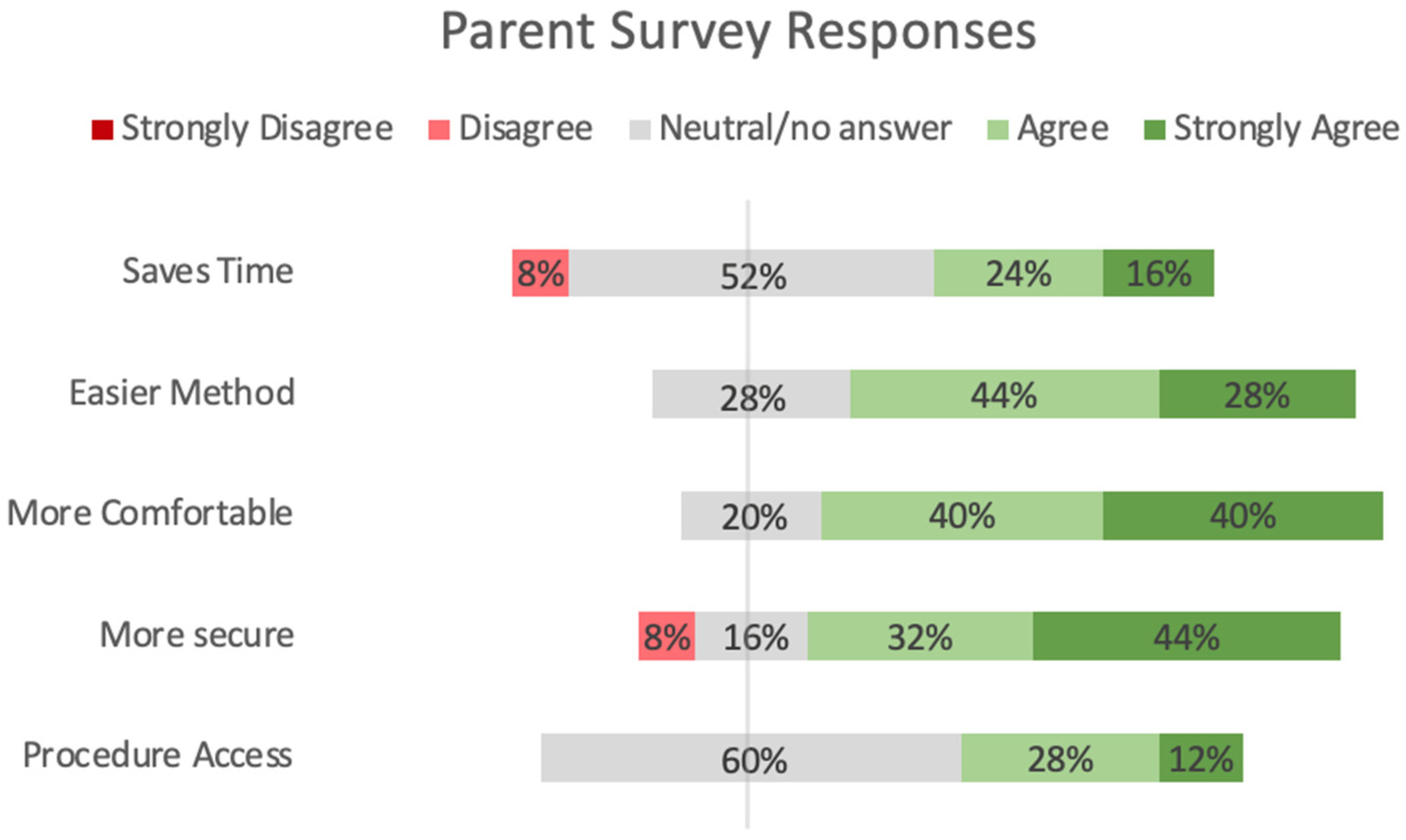

Figure 5 shows the results from parents and surveys comparing the Kangarobe™ to the traditional ad hoc method of KC. Survey questions were categorized into five domains: time savings, ease of use, comfort, security, and procedure access (via vertical access window). There was a preponderance of positive responses, “strongly agree” or “agree” (72% and 80%, respectively), and no negative responses in the domains of ease of use and comfort. For the security of lines, there was still a predominantly positive response (76%), with four (16%) neutral responses and two (8%) negative (“disagree”) responses. Twelve parents did not answer the question about procedure access, either because it was not used or because that question was deferred to the nursing staff. Of those 13 parents who responded, 40% were positive, 60% were neutral, and none were negative.

Similarly,

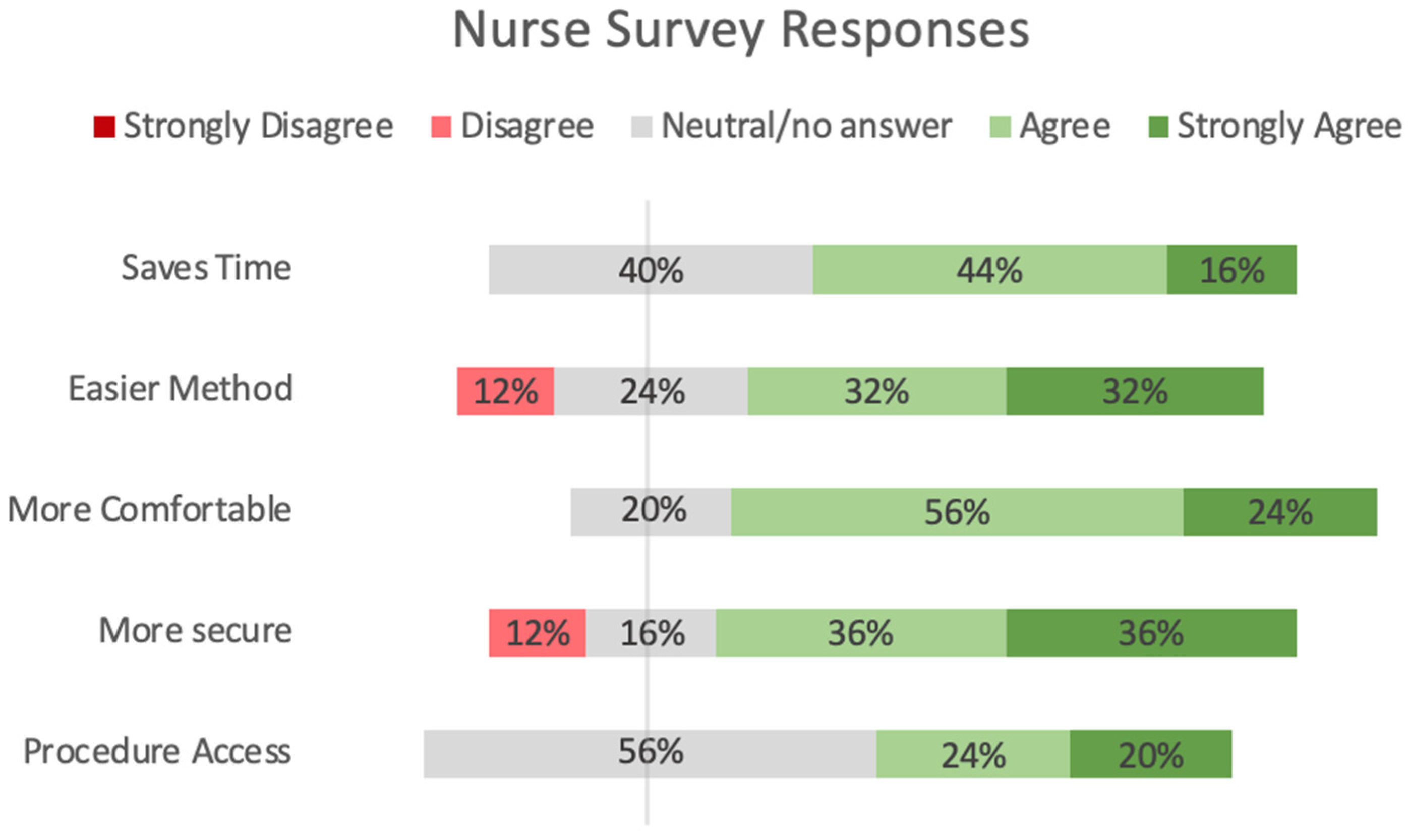

Figure 6 shows the results from the nurse surveys in the same five domains. For them, there were predominantly positive responses for time savings and comfort, 60% and 80%, respectively, with the remainder being neutral. For ease of use and security, positive responses dominated (64% and 72%), with some neutral responses (24% and 16%) and a few (12%) negative (“disagree”) answers. Not all nurses answered the question regarding the procedure access via the vertical window; of the 16 who did, 44% were positive, 56% were neutral, and none were negative.

The chart illustrates a summary of the 25 nurse responses to the survey. Neutral responses to question 5 about the vertical access window may reflect that it was not used. No one who used the vertical access window disliked it.

4. Discussion

Extensive research has demonstrated that KC in the NICU is closely associated with improved health outcomes for premature infants, both in the short and long term [

14]. Despite its many benefits, KC for premature infants is underutilized due to several barriers including concerns regarding safety, comfort, and privacy during transfer and holding, and security of baby’s lines and respiratory tubing.

Input from NICU staff and parents was integral to the iterative design process for the Kangarobe™. Gathering user feedback early and frequently throughout the rapid prototyping process is crucial to identify promising solutions and refine prototypes quickly for further testing. While this feasibility study is limited in size and scope, we have illustrated that the Kangarobe™ is promising as a safe and efficient KC device for babies with multiple lines and tubes. The results suggest that the implementation of the Kangarobe™ offers an improved KC experience for infants, nurses, and parents in the NICU, with the potential for improving patient safety, healthcare staff efficiency, and supporting family-centered care.

The involvement of nurses is crucial, as they are integral in guiding and supporting mothers through the KC process. Nurses provide emotional support and practical assistance, teaching mothers how to provide primary care such as breastfeeding and hygiene, and specialized care such as oral drug administration. Further, KC initiated early and practiced often provides numerous benefits. Mothers report enhanced attachment, increased milk production, and more successful breastfeeding, while fathers also report increased bonding and confidence in providing care. Notably, both parents experience decreased levels of anxiety during KC, and infants exhibit decreased stress responses [

7].

In reviewing the survey data, several key insights emerge that warrant discussion. Despite the limited participant pool, certain trends and feedback patterns offer valuable preliminary insights. Notably, participants consistently reported positive responses to the intervention’s usability and comfort, reinforcing existing literature on its acceptability and potential for enhancing infant care. However, some feedback highlighted specific limitations, such as occasional discomfort during extended use, suggesting areas for refinement in future designs. These insights, though based on a small cohort, align with the known benefits of similar interventions, adding to the body of evidence supporting its use in neonatal care. The survey results also indicate directions for future research, such as further testing with a larger, more diverse population to validate these initial findings and explore demographic variations. Additionally, this feedback provides a basis for practical adjustments, ensuring the intervention meets the needs of caregivers and healthcare providers more effectively.

The Kangarobe™ has the potential to significantly impact clinical workflow and nursing workload in the NICU. By providing a garment designed for safe and continuous skin-to-skin contact, it could streamline care procedures by reducing the need for constant repositioning and monitoring typically required for preterm infants. This enhanced stability could allow nurses to feel more confident leaving infants in the Kangarobe™ for longer durations, thereby freeing up time for other critical tasks. Additionally, the Kangarobe™‘s compatibility with various respiratory devices, such as nasal cannulas and ventilator tubing, could simplify device management, reducing the complexity and frequency of adjusting equipment during skin-to-skin sessions. This efficiency may not only enhance the quality of care provided to each infant but could also lower the physical and cognitive demands on nurses, potentially reducing fatigue and improving overall workflow in the NICU. Moreover, by providing a safer and more effective means for parents to engage in Kangaroo Care, the Kangarobe™ supports family involvement in the caregiving process, potentially lightening the emotional workload on nursing staff by sharing some aspects of care with parents. However, further research is needed to quantify these potential benefits and assess the Kangarobe™’s impact on NICU workflow and nursing efficiency.

The integration of the Kangarobe™ can enhance the KC experience for infants, nurses, and parents in the NICU. By addressing the logistical challenges associated with traditional KC, the Kangarobe™ can facilitate increased adoption of this beneficial practice. Notably, this innovation also holds the potential to enhance patient safety, and healthcare staff efficiency, and support family-centered care, provided that nurses continue to play their supportive role efficiently and compassionately in the NICU [

8].

5. Limitations

There are limitations to this study that need to be acknowledged. The participant pool in this study was limited, and a larger cohort would be advantageous to validate these findings. Additionally, there needs to be a demonstration of safe use with higher acuity support devices (endotracheal tubes and tracheostomy tubes) whose stability is more critical to patient safety compared to lower acuity devices. With simulation training sessions nurses may be more comfortable and confident with the use of the Kangarobe™. Furthermore, some parents were significantly more comfortable with KC due to having more extensive experience transferring the infants from bed to parent. This could impact the data by lowering the transfer time. Finally, we did not compare the duration of the hold of each individual parent performing KC with the Kangarobe™ versus using a different garment with subsequent holding events.

6. Conclusions

Kangaroo Care (KC) has significant benefits for preterm and infants with low birth weight admitted to the NICU. To facilitate the widespread use of KC in the NICU, it is important for the NICU to have readily available support devices, which facilitate a comfortable experience for the parent and infant, while also securing lines that support the baby. In this study, we tested the Kangarobe™, a belted wrap garment designed to facilitate safe and efficient caregiver skin-to-skin holding for babies in the NICU with multiple medical devices. The garment integrates multiple snap fasteners and loops with disposable Velcro® to secure medical support devices the infant requires, as well as an easy-access vertical window to allow evaluations of the infant including heel sticks and wound checks without disturbing KC. The Kangarobe™ provides multiple secure attachment points for medical lines and ventilation tube routing, safe infant support while the parent holds, and easy access to the baby by nurses. The highly positive user responses from both NICU nurses and parents demonstrate the benefits of using their feedback to design a garment to better support KC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.A.C. and J.P.S.; formal analysis: A.M., W.D.R. and A.P.A.; funding acquisition: R.A.C. and J.P.S.; investigation: A.M., W.D.R. and A.P.A.; methodology: R.A.C., J.P.S., W.D.R. and A.P.A.; project administration: A.M.; supervision: W.D.R. and A.P.A.; validation: A.M., A.P.A. and W.D.R.; writing—original draft: A.P.A., A.M. and W.D.R.; writing—review and editing: A.P.A., A.M., R.A.C., J.P.S. and W.D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Consortium for Technology & Innovation in Pediatrics and the UCSF-Stanford Pediatric Device Consortium.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, protocol code 60251, on 30 June 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects in this study (nurses and parents).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns governed by HIPAA regulations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the NICU parents, nurses, respiratory therapists, and neonatologists at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford and El Camino Hospital for their invaluable feedback and assistance in completing this study. Special thanks to Ringit Gurlich, an expert soft goods designer, whose skills and insights significantly enhanced the development of the Kangarobe™.

Conflicts of Interest

Ruth Ann Crystal and Jules Sherman are the inventors of the Kangarobe.

Patent

U.S. Patent No. 11,819,142 · Issued 21 November 2023.

References

- Ruiz-Peláez, J.G.; Charpak, N.; Cuervo, L.G. Kangaroo Mother Care, an example to follow from developing countries. BMJ 2004, 329, 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cristóbal Cañadas, D.; Parrón Carreño, T.; Sánchez Borja, C.; Bonillo Perales, A. Benefits of Kangaroo Mother Care on the Physiological Stress Parameters of Preterm Infants and Mothers in Neonatal Intensive Care. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Charpak, N.; Ruiz, J.G.; Zupan, J.; Cattaneo, A.; Figueroa, Z.; Tessier, R.; Cristo, M.; Anderson, G.; Ludington, S.; Mendoza, S.; et al. Kangaroo Mother Care: 25 years after. Acta Paediatr. 2005, 94, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludington-Hoe, S.M. Evidence-based review of physiologic effects of kangaroo care. Curr. Women’s Health Rev. 2011, 7, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivanandan, S.; Sankar, M.J. Kangaroo mother care for preterm or low birth weight infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 2023, 8, e010728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eskandari, S.; Mirhaghjou, S.N.; Maryam Maleki, M.; Mardani Gholami, M.; Harding, C. Identification of the Range of Nursing Skills Used to Provide Social Support for Mothers of Preterm Infants in Neonatal Intensive Care. Crit. Care Res. Pract. 2021, 2021, 6697659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maleki, M.; Mardani, A.; Harding, C.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Vaismoradi, M. Nurses’ strategies to provide emotional and practical support to the mothers of preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Women’s Health 2022, 18, 17455057221104674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saptaputra, S.K.; Kurniawidjaja, M.; Susilowati, I.H.; Pratomo, H. How to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of Kangaroo Mother Care: A literature review of equipment supporting continuous Kangaroo Mother Care. Gac. Sanit. 2021, 35 (Suppl. S1), S98–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penn, S. Overcoming the barriers to using kangaroo care in neonatal settings. Nurs. Child. Young People 2015, 27, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidman, G.; Unnikrishnan, S.; Kenny, E.; Myslinski, S.; Cairns-Smith, S.; Mulligan, B.; Engmann, C. Barriers and enablers of kangaroo mother care practice: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weber, A.; Jackson, Y. A Survey of Neonatal Clinicians’ Use, Needs, and Preferences for Kangaroo Care Devices. Adv. Neonatal Care 2021, 21, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gaulton, J.; Crowe, B.; Sherman, J. How Design Thinking and Quality Improvement Can Be Integrated into a “Human-Centered Quality Improvement” Approach to Solve Problems in Perinatology. Clin. Perinatol. 2023, 50, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarah, G. Design Thinking 101. Nielsen Norman Group, 31 July 2016. Available online: www.nngroup.com/articles/design-thinking/ (accessed on 15 May 2019).

- Charpak, N.; Tessier, R.; Ruiz, J.G.; Hernandez, J.T.; Uriza, F.; Villegas, J.; Nadeau, L.; Mercier, C.; Maheu, F.; Marin, J.; et al. Twenty-year Follow-up of Kangaroo Mother Care Versus Traditional Care. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20162063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).