Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Community Engagement

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Analysis

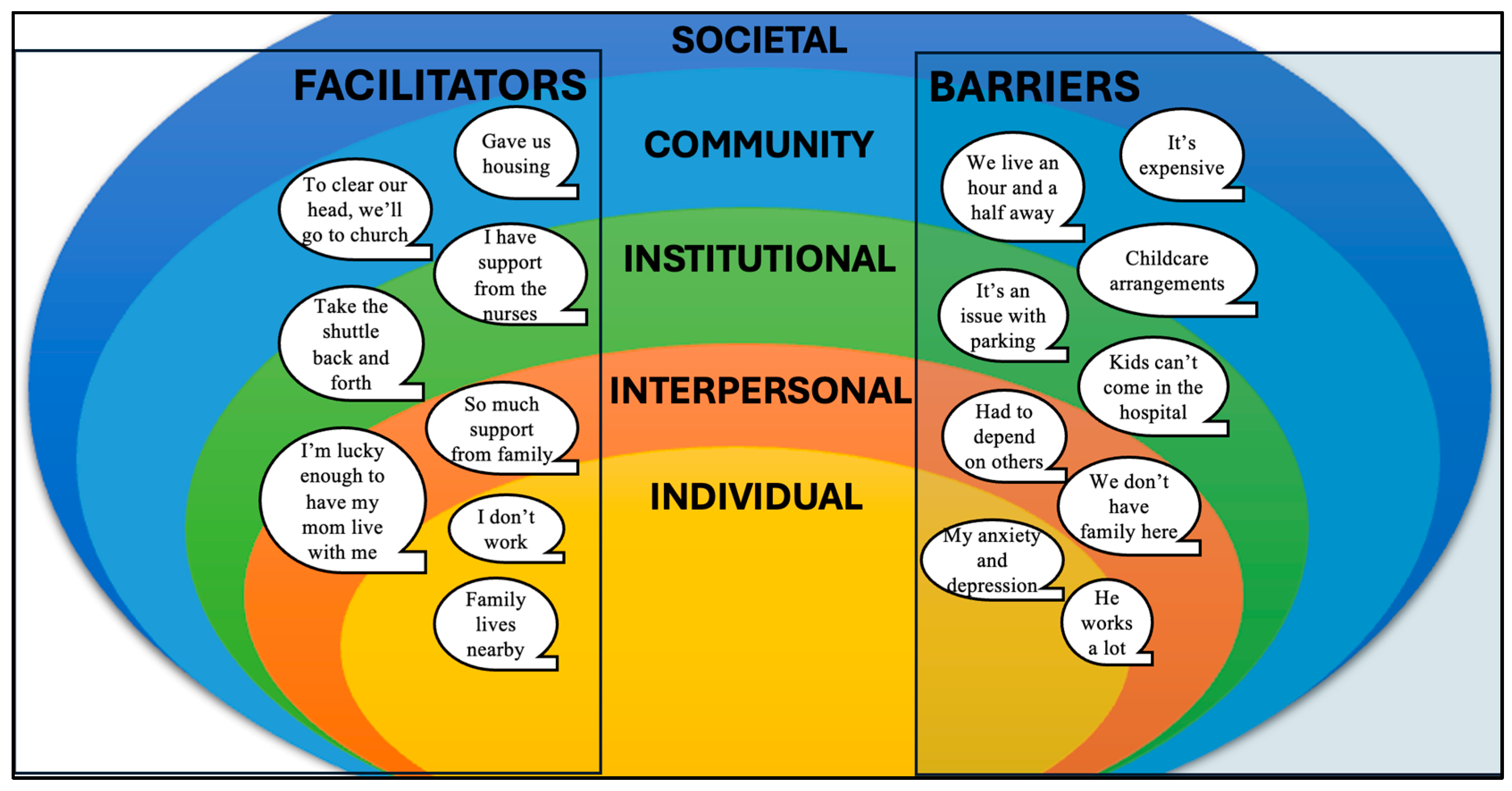

3.2.1. Barriers to Maternal Presence

“I know they mentioned to me there was a [parking] pass or something I could get…And then once I was able to bring myself, I was able to come as I could in between the other children being in school and have to be picked up and doctor’s appointments and all that good stuff. So, I have to come in between all of that going on?”(Mom 5)

3.2.2. Facilitators to Maternal Presence

“And I do realize that I’m in a unique circumstance where I am a stay-at-home parent and my mother, she doesn’t have a formal job…So, I have family to watch my kids and I’m flexible with time. That is not the case for the majority of parents I would say.”(Mom 1)

“I am driving, but just to save with money and parking in the parking garage, I do take the shuttle back and forth. That’s one of the best things honestly.”(Mom 11)

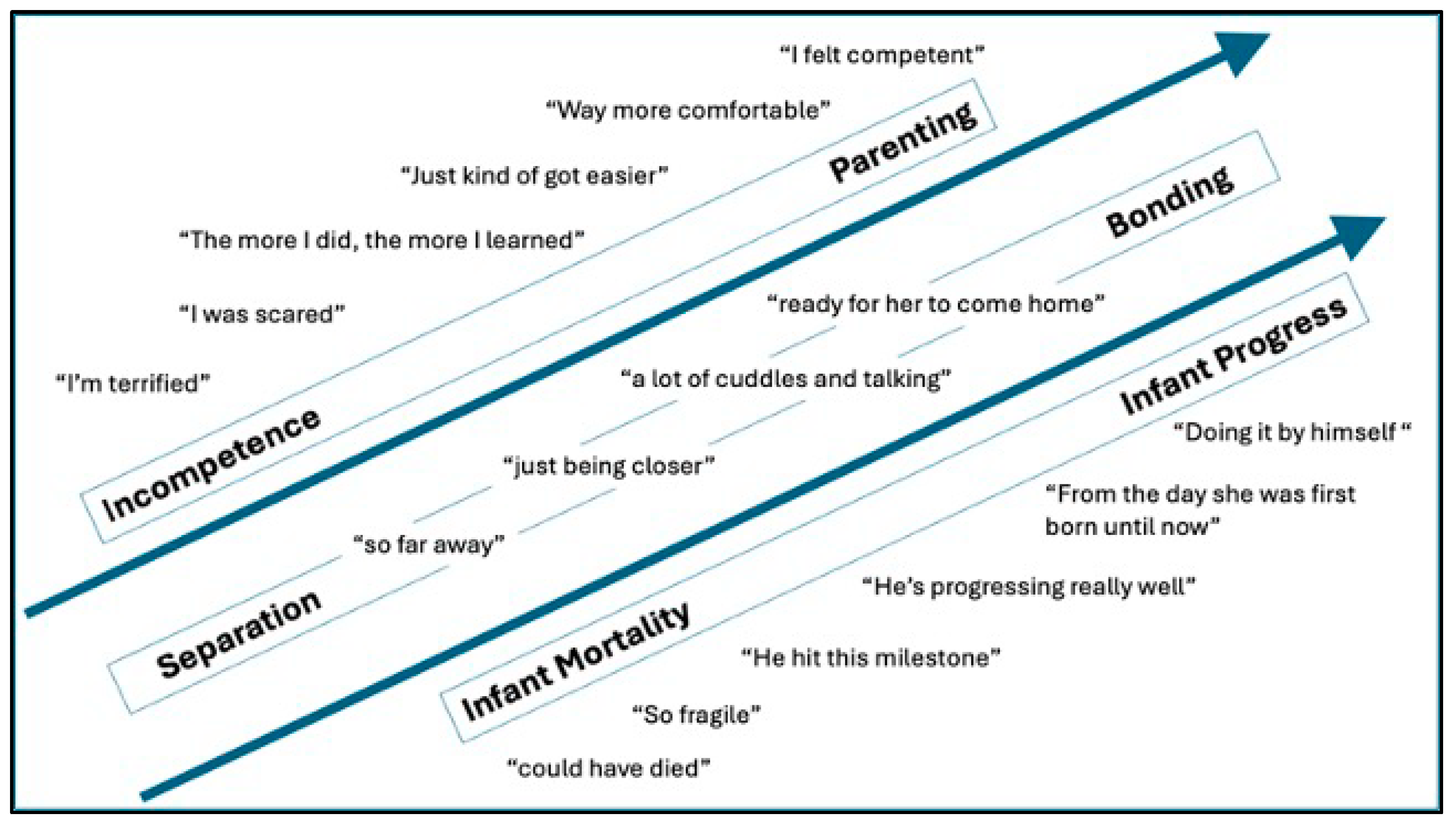

3.2.3. NICU Experience

“You sit there and wonder when he’s coming home, when he’s coming home. And for us, there’s been moments where we think we can start to see the finish line, and inevitably something happens that prolongs his stay even more.”(Mom 12)

“…you miss a lot of firsts. You miss the first holding him. You miss the first diaper change. You miss his first outfit. You miss a lot of stuff.”(Mom 1)

“So, going from one pound to five pounds is just amazing. I’m watching her grow outside my womb. It’s just amazing. It’s amazing. It really is.”(Mom 10)

“Well, at first, really, all I could really do was hold her because she was just so small. She couldn’t do anything. But, now, I’m able to feed her, hold her, dress her, change her…So, now, it’s a little bit better now.”(Mom 9)

3.2.4. Interpersonal Interactions

So, that’s why I was saying those nurses were giving me confidence. They were just like, “Come on, we’re here. We’re not going to let nothing happen. We’ve got monitors. We can stay in here and watch you. Whatever is comfortable for you.”(Mom 10)

…the nurses are there in person telling me, “Listen, this is normal. It happens. We’re here to help.” And they made me feel so much better.(Mom 11)

They will not fully change his dressing. All they do is wipe off the little plastic piece that they put over it….That can cause him to get an infection. That’s what worries me.(Mom 7)

“Why did no one call me when my child moved? I haven’t had an update in four days. What’s happening?”(Mom 1)

Well, it kind of depended on the nurse because some are like because he was connected to so much, you know, they prefer that you’re able to stay, you know, an hour or more. I mean, sometimes let’s face it, I can’t stay as long—(Mom 5)

I asked them about [free housing] a couple of months ago right after I had him. I went home because they didn’t let me know anything about this at the hospital.(Mom 7)

3.2.5. Trustworthiness

“While he’s talking to me, he’s rubbing [the infant] on the head, just being very personable like he cares for this little baby. That eases me so much.”(Mom 3)

“It’s the way they talk and they actually let me hands-on and help.”(Mom 7)

“There are people who are on top of it, and there are people who are on top of cares and on top of feeding where they don’t make it feel like a chore.”(Mom 4)

“So, that can kind of make you lose trust and confidence in somebody if you hear them complaining about a parent when they’re not there.”(Mom 2)

3.2.6. Emotions

“Yeah. You want to comfort, you want to soothe, but you can’t. You can’t do anything. All you can do is just watch her through a glass and she has to fight for herself.”(Mom 2)

“I think the first time I held her, she was like maybe two weeks old, because I was scared to hold her. There was no way you could hold her. I was like, “I am scared.’”(Mom 10)

3.2.7. Shared Medical Decision-Making

The way she talked, wasn’t like, ‘I’m an expert and I know better’….It was more like, ‘Okay…Tell me what you think and I’ll tell you my professional opinion.’ They were like, ‘We’ll give you guys time. We’ll give her time, and once time runs out, then we’ll start discussing it.’”(Mom 2)

“But as far as I’m not comfortable with this or that, I don’t think they really care. They’re like, ‘Well, we’re going to do it anyway because it’s what he needs. But we want you to know why.’”(Mom 3)

3.2.8. Bias

“I’m trying to think. Pretty much everybody on her care team is the opposite color….Definitely not. I’ve never felt that way.”(Mom 2)

“No, I don’t think I’ve ever experienced anything negative. I was told from one nurse…that this is a hospital [that] cares so much about mothers, especially Black mothers.”(Mom 11)

“…there was one nurse in particular that kind of made me—kind of belittled me, I felt like, as a mom.”(Mom 12)

“…felt like some of the older staff, like more towards grandparents age, they seem to talk down on the younger parents. I’ve had quite a few dirty looks when I take down my mask because I have a good amount of piercings.”(Mom 4)

3.3. Community Engagement: Family Advisory Board Collaborative Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Interview Guide

| Semi-structured questions |

| Opening Question |

| I am going to talk with you about your overall experience visiting your baby in the NICU. |

Your baby has been in the hospital for X months, right? What has this experience been like for you?

|

| Structural and Institutional Barriers and Facilitators |

Let us talk about your visits. First, before we even get to your time with your baby, could you describe how you get to the hospital?

|

| How has it been for you to be separated from your baby? |

| How long is your commute to the hospital? |

| What were the things that made difficult to visit your baby on a regular basis? |

| In times that you did get to see your baby and it didn’t feel difficult, what made those visits easier? |

| Individual Perceptions |

What are your visits like?

|

What kinds of things do you do when you visit your baby?

|

Would you say you feel comfortable doing these activities (eg., diapering, feeding, holding)?

|

Do you feel like a member of your baby’s medical team?

|

| Interpersonal Interactions |

| I am going to talk with you some about your interactions with different health care practitioners/clinicians that you’ve met in the hospital… |

Since you’ve been here with your baby in the hospital, what kind of health care practitioners/clinicians have you met?

|

Of the different health care practitioners you have met, which ones have talked with you about how things are going with your baby, how to care for your baby, etc.?

|

What kind of things have health care practitioners talked to you about or taught you during your baby’s hospitalization?

|

Have you had an experience with a health care practitioners/clinicians where you didn’t have all of your questions answered?

|

When you think of the health care practitioners/clinicians you’ve engaged with, who comes to mind as trustworthy? Feel free to think of more than one person.

|

| If you could tell your baby’s health care practitioners/clinicians anything you would like for them to know about how to better interact with you and/or other mothers like you, what would it be? |

References

- March of Dimes. 2023 March of Dimes Report Card. 2023. Available online: https://www.marchofdimes.org/report-card (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Kuban, K.C.; Allred, E.N.; O′Shea, M.; Paneth, N.; Pagano, M.; Leviton, A.; ELGAN Study Cerebral Palsy-Algorithm Group. An algorithm for identifying and classifying cerebral palsy in young children. J. Pediatr. 2008, 153, 466–472.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuban, K.C.; Joseph, R.M.; O’Shea, T.M.; Allred, E.N.; Heeren, T.; Douglass, L.; Stafstrom, C.E.; Jara, H.; Frazier, J.A.; Hirtz, D.; et al. Girls and Boys Born before 28 Weeks Gestation: Risks of Cognitive, Behavioral, and Neurologic Outcomes at Age 10 Years. J. Pediatr. 2016, 173, 69–75.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winberg, J. Mother and newborn baby: Mutual regulation of physiology and behavior—A selective review. Dev. Psychobiol. 2005, 47, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White-Traut, R.; Wink, T.; Minehart, T.; Holditch-Davis, D. Frequency of premature infant engagement and disengagement behaviors during two maternally administered interventions. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2012, 12, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Als, H.; Gilkerson, L. The role of relationship-based developmentally supportive newborn intensive care in strengthening outcome of preterm infants. Semin. Perinatol. 1997, 21, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrup, B. Family-centered developmentally supportive care: The Swedish example. Arch. Pediatr. 2015, 22, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, R.; Bender, J.; Hall, B.; Shabosky, L.; Annecca, A.; Smith, J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Hum. Dev. 2018, 117, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, N.M.; Vittner, D.; Samra, H.A.; McGrath, J.M. The PREEMI as a measure of parent engagement in the NICU. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 47, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, R.M.; MA, E.K.M.; Tucker, C.; Charles, N.; Verbiest, S.; Lewis, V.; Bryant, K.; Stuebe, A.M. Postpartum Health Experiences of Women with Newborns in Intensive Care: The Desire to Be by the Infant Bedside as a Driver of Postpartum Health. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, M.M.; Rossman, B.; Patra, K.; Kratovil, A.; Khan, S.; Meier, P.P. Maternal psychological distress and visitation to the neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, e306–e313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nist, M.D.; Spurlock, E.J.; Pickler, R.H. Barriers and facilitators of parent presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child. Nurs. 2024, 49, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Head Zauche, L.; Zauche, M.S.; Dunlop, A.L.; Williams, B.L. Predictors of parental presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv. Neonatal Care 2020, 20, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garten, L.; Maass, E.; Schmalisch, G.; Bührer, C. O father, where art thou? Parental NICU visiting patterns during the first 28 days of life of very low-birth-weight infants. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2011, 25, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehill, L.; Smith, J.; Colditz, G.; Le, T.; Kellner, P.; Pineda, R. Socio-demographic factors related to parent engagement in the NICU and the impact of the SENSE program. Early Hum. Dev. 2021, 163, 105486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, A.L.; Fletcher, F.E.; Kadono, M.; Warren, R.C. Institutional Distrust among African Americans and Building Trustworthiness in the COVID-19 Response: Implications for Ethical Public Health Practice. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2021, 32, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder, K.; White, K.O.; Woodhams, E.; Pancholi, R.; Yinusa-Nyahkoon, L. Racism and the Reproductive Health Experiences of U.S.-Born Black Women. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, R.E.; Colvin, B.N.; Lenze, S.N.; Forbes, E.S.; Parker, M.G.K.; Hwang, S.S.; Rogers, C.E.; Colson, E.R. Lived experiences of stress of Black and Hispanic mothers during hospitalization of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units. J. Perinatol. 2022, 42, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, R.E.; Malcolm, M.; Colvin, B.N.; Gill, M.M.R.; Ofori, J.; Roy, S.; Lenze, S.N.; Rogers, C.E.; Colson, E.R. Racism and quality of neonatal intensive care: Voices of black mothers. Pediatrics 2022, 150, e2022056971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonya, J.; Nelin, L.D. Factors associated with maternal visitation and participation in skin-to-skin care in an all referral level IIIc NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2013, 102, e53–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.P.; York, R.; Jacobsen, B.; Gennaro, S.; Brooten, D. Very low birth-weight infants: Parental visiting and telephoning during initial infant hospitalization. Nurs. Res. 1989, 38, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, E.J.; Brasted, W.S.; Myerberg, D.Z.; Hamilton, S. Prolonged travel time to neonatal intensive care unit does not affect content of parental visiting: A controlled prospective study. J. Rural Health 1991, 7, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacoia, G.P.; Rutledge, D.; West, K. Factors affecting visitation of sick newborns. Clin. Pediatr. 1985, 24, 259–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, J.T.; Ford, C.L.; Wallace, S.P.; Wang, M.C.; Takahashi, L.M. Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the united states. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redefining Urban Areas Following the 2020 Census. Available online: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2022/12/redefining-urban-areas-following-2020-census.html (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Making Sense of the New “Urban Area” Definitions. NC OSBM. Available online: https://www.osbm.nc.gov/blog/2023/01/09/making-sense-new-urban-area-definitions (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Makkar, A.; McCoy, M.; Hallford, G.; Escobedo, M.; Szyld, E. A hybrid form of telemedicine: A unique way to extend intensive care service to neonates in medically underserved areas. Telemed. E-Health 2018, 24, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.; Hart, L.G.; Goodman, D.C. Geographic access to health care for rural Medicare beneficiaries. J. Rural Health 2006, 22, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, L.C.; Adkins-Jackson, P.B. Mixed-Method, Multilevel Clustered-Randomized Control Trial for Menstrual Health Disparities. Prev. Sci. 2024, 25, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, F.; Kang, M.; Steinbeck, K.; Hawke, C.; Jan, S.; Sanci, L.; Liew, Y.Y.; Kong, M.; Usherwood, T. Health care equity and access for marginalised young people: A longitudinal qualitative study exploring health system navigation in Australia. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, E.; Dowshen, N.L.; Baker, K.E. Intersectionality and health inequities for gender minority blacks in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 59, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narine, D.; Yamashita, T.; Mair, C.A. An Intersectional Approach to Examining Breast Cancer Screening among Subpopulations of Black Women in the United States. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, E.R. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.M.; Shahidullah, J.D.; Lassen, S.R. Development of postpartum depression interventions for mothers of premature infants: A call to target low-SES NICU families. J. Perinatol. 2020, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, A.; Ziglio, E. Revitalising the evidence base for public health: An assets model. Promot. Educ. 2007, 14, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, L.S. Trust, risk, and race in american medicine. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020, 50, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, E.A.; Rolle, I.; Ferrans, C.E.; Whitaker, E.E.; Warnecke, R.B. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2006, 21, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshire, J.; Allison, J.J.; Brown, R.; Elder, K. African American women perceptions of physician trustworthiness: A factorial survey analysis of physician race, gender and age. AMS Public Health 2018, 5, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. NVivo; Lumivero: Denver, CO, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- RMH of Chapel Hill—Ronald McDonald House Charities of the Triangle. Available online: https://rmhctriangle.org/our-programs/rmh-of-chapel-hill/ (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Kilanowski, J.F. Breadth of the Socio-Ecological Model. J. Agromed. 2017, 22, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You Decide: Is It Cheaper to Live in North Carolina? College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. Available online: https://cals.ncsu.edu/news/you-decide-is-it-cheaper-to-live-in-north-carolina/ (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Miroševič, Š.; Prins, J.; Borštnar, S.; Besić, N.; Homar, V.; Selič-Zupančič, P.; Smrdel, A.C.; Klemenc-Ketiš, Z. Factors associated with a high level of unmet needs and their prevalence in the breast cancer survivors 1–5 years after post local treatment and (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy during the COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 969918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.; Halkett, G.K.B.; Lobb, E.A.; Shaw, T.; Hovey, E.; Nowak, A.K. Carers of patients with high-grade glioma report high levels of distress, unmet needs, and psychological morbidity during patient chemoradiotherapy. Neuro-Oncol. Pract. 2016, 3, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, T.P.; Andrews, K.G.; Shenberger, E.; Betancourt, T.S.; Fink, G.; Pereira, S.; McConnell, M. Caregiving can be costly: A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to conducting kangaroo mother care in a US tertiary hospital neonatal intensive care unit. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northrup, T.F.; Evans, P.W.; Lillie, M.L.; Tyson, J.E. A free parking trial to increase visitation and improve extremely low birth weight infant outcomes. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, K.G.; Martin, M.W.; Shenberger, E.; Pereira, S.; Fink, G.; McConnell, M. Financial Support to Medicaid-Eligible Mothers Increases Caregiving for Preterm Infants. Matern. Child. Health J. 2020, 24, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, K.; Buckman, C.; Naik, T.K.; Tumin, D.; Kohler, J.A. Ronald McDonald House accommodation and parental presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 2570–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, C.S.; Passmore, S.R.; Maietta, R.C.; Petruzzelli, J.; Casper, E.; Brown, N.A.; Butler, J., 3rd; Garza, M.A.; Thomas, S.B.; Quinn, S.C. The symbolic value and limitations of racial concordance in minority research engagement. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, L. Listening to Black Californians: How the Healthcare System Undermines Their Pursuit of Good Health. California Health Care Facility. October 2022, pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/LBCAExecSummary.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Hendricks-Muñoz, K.D.; Li, Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Prendergast, C.C.; Mayers, R.; Louie, M. Maternal and neonatal nurse perceived value of kangaroo mother care and maternal care partnership in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 875–880. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.E.; D’Agostino, J.A.; Passarella, M.; Lorch, S.A. Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care. J. Perinatol. 2016, 36, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, S.; Michelin, N.; Amrani, E.; Benier, B.; Durrmeyer, X.; Lescure, S.; Bony, C.; Danan, C.; Baud, O.; Jarreau, P.-H.; et al. Parents’ expectations of staff in the early bonding process with their premature babies in the intensive care setting: A qualitative multicenter study with 60 parents. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Understand the Difference Between Social Status and Social Class|by Zachary Williams|Medium. Available online: https://medium.com/@fatemiima2/understand-the-difference-between-social-status-and-social-class-e5a8baffefa3 (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Definitions. Available online: https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/class/definitions (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Connor, P.; Varney, J.; Keltner, D.; Chen, S. Social class competence stereotypes are amplified by socially signaled economic inequality. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, P.; Weeks, M.; Glaser, J.; Chen, S.; Keltner, D. Intersectional implicit bias: Evidence for asymmetrically compounding bias and the predominance of target gender. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 124, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.N.; Bodenhausen, G.V.; Milne, A.B. The dissection of selection in person perception: Inhibitory processes in social stereotyping. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, D.B.; Letzkus, L.; Attridge, E.; Dusing, S.C. Efficacy of Therapist Supported Interventions from the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit to Home: A Meta-Review of Systematic Reviews. Clin. Perinatol. 2023, 50, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarty, D.B.; Dusing, S.C.; Thorpe, D.; Weinberger, M.; Pusek, S.; Gilbert, A.; Liu, T.; Blazek, K.; Hammond, S.; O’shea, T.M. A Feasibility Study of a Physical and Occupational Therapy-Led and Parent-Administered Program to Improve Parent Mental Health and Infant Development. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2024, 44, 316–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.H.; Sexton, J.; Sriram, N.; Cooper, L.A.; Efron, D.T.; Swoboda, S.; Villegas, C.V.; Haut, E.R.; Bonds, M.; Pronovost, P.J.; et al. Association of unconscious race and social class bias with vignette-based clinical assessments by medical students. JAMA 2011, 306, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.H.; Schneider, E.B.; Sriram, N.; Dossick, D.S.; Scott, V.K.; Swoboda, S.M.; Losonczy, L.; Haut, E.R.; Efron, D.T.; Pronovost, P.J.; et al. Unconscious race and social class bias among acute care surgical clinicians and clinical treatment decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornsdottir, R.T.; Beacon, E. Stereotypes bias social class perception from faces: The roles of race, gender, affect, and attractiveness. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2024, 77, 2339–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, R.; Li, X.; Han, Q. The relationship between social class and generalized trust: The mediating role of sense of control. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 729083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John-Henderson, N.; Jacobs, E.G.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Francis, D.D. Wealth, health, and the moderating role of implicit social class bias. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 45, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-B.; Chen, C.; Pan, X.-F.; Guo, J.; Li, Y.; Franco, O.H.; Liu, G.; Pan, A. Associations of healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: Two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2021, 373, n604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, A.J.; Farmer, M.L.; D’Agata, A.; Moore, T.; Esser, M.; Fortney, C.A. NANN membership recommendations: Opportunities to advance racial equity within the organization. Adv. Neonatal Care 2024, 24, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayingo, G.; Bradley-Guidry, C.; Burwell, N.; Suzuki, S.; Dorough, R.; Bester, V. Assessing and benchmarking equity, diversity, and inclusion in healthcare professions. JAAPA 2022, 35, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singletary, K.A.; Chin, M.H. What should antiracist payment reform look like? AMA J. Ethics. 2023, 25, E55–E65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Washington, A.; Randall, J. “We’re not taken seriously”: Describing the experiences of perceived discrimination in medical settings for black women. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2023, 10, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, V.B.; Mays, D.; LaVeist, T.; Tercyak, K.P. Medical mistrust influences black women’s level of engagement in BRCA 1/2 genetic counseling and testing. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2013, 105, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samanta, D.; Elumalai, V.; Leigh Hoyt, M.; Modi, A.C.; Sajatovic, M. A qualitative study of epilepsy self-management barriers and facilitators in Black children and caregivers in Arkansas. Epilepsy Behav. 2022, 126, 108491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, A.; Fischer, H. “Don’t call me ‘mom’”: How parents want to be greeted by their pediatrician. Clin. Pediatr. 2009, 48, 720–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Maternal Age | Maternal Race | Infant Gestational Age | Length of Hospitalization at Time of Interview | Home Address Distance in Miles from NICU | Other Children | Working Outside of the Home at Time of Interview | Partner | Access to Free Living Accommodations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mom 1 | 33 | W | 29 w 4 d | 8 weeks | 38 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, family |

| Mom 2 | 31 | B | 23 w 1 d | 13 weeks, 2 days | 74 | No | No | Yes | Yes, RMH |

| Mom 3 | 30 | W | 30 w 0 d | 4 weeks, 4 days | 76 | Yes | No | Yes | No, commuting |

| Mom 4 | 20 | W | 27 w 0 d | 6 weeks, 4 days | 33 | No | No | Yes | No, commuting |

| Mom 5 | 36 | B | 27 w 5 d | 9 weeks, 3 days | 39 | Yes | No | No | No, commuting |

| Mom 6 | 39 | B | 24 w 6 d | 13 weeks, 1 days | 43 | Yes | No | No | No, commuting |

| Mom 7 | 34 | W | 32 w 1 d | 8 weeks, 5 days | 55 | No | No | Yes | Yes, RMH |

| Mom 8 | 30 | B | 25 w 2 d | 10 weeks | 90 | Yes | No | No | Yes, RMH |

| Mom 9 | 21 | B | 26 w 0 d | 11 weeks | 68 | No | Yes | Yes | No, commuting |

| Mom 10 | 28 | B | 26 w 1 d | 11 weeks, 2 days | 38 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes, RMH |

| Mom 11 | 26 | B | 31 w 0 d | 3 weeks, 3 days | 46 | No | No | No | Yes, RMH |

| Mom 12 | 28 | W | 26 w 6 d | 11 weeks, 4 days | 84 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes, RMH |

| Code | Definition | Subcode | Definition | In Vivo Phrases Examples | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barriers to Visitation | Descriptions of logistical challenges and/or resource- or time-related barriers to hospital visitation | Distance of Commute | Distance traveled; time necessary to travel from home to hospital | “going back and forth” | |

| Resource strains | Financial strains to support costs of gas, parking, and food while away from home | “It’s expensive” “depending on gas prices” | |||

| Institutional Barriers | Difficulty navigating parking logistics, hospital check-in, visitation policies | “it’s an issue with parking” | |||

| Responsibilities outside of infant care | Visitation limited by work hours (either mother or mother’s partner) and caregiving responsibilities | “I had to depend on others” “depends on childcare” | |||

| Mother’s health/recovery | Mother’s own health care appointments and/or restrictions on driving | “I was also sick” “anxiety and depression that I’ve had” | |||

| Facilitators to Visitation | Descriptions of maternal supports that make regular visitation more feasible | Family and/or social supports | Family and/or community assistance in ways that facilitate the mother’s visits | “so much support from…family” | |

| Job flexibility and/or resource provision | Flexibility in mother’s or partner’s work or finances that facilitate visits | “works from home” “husband works” | |||

| Housing | Having a place to stay locally | “gave us housing” “lives nearby” | |||

| NICU Experience | Mother’s perceptions of the experience of having a preterm infant in the NICU | Positive | Bonding | Holding, cuddling, skin-to-skin care, or other developmentally appropriate interactions with infant | “ready to love on her” “that was special” “get to hold him” |

| Parenting | Activities related to caring for infant including feeding and diapering | “I feed her myself, everything” “I’m like, I’m his mom, I change his diaper” | |||

| Infant Progress | Descriptions of how far the infant has come regarding health since birth | “Look how far she’s come” “I can’t believe this is the same baby” | |||

| Negative | Separation | Difficulty being separated from infant and/or family members | “ready for her to come home” “I’m not whole” | ||

| Incompetence | Not sure how to care for infant or how to feel about infant | “I don’t know” “it’s just different” “you question yourself” | |||

| Infant mortality | Concerns about infant’s risk of death or staying/becoming sick | “laying there lifeless” “so fragile” “literally, in the palm of your hands” | |||

| Interpersonal Interactions | Mother’s descriptions of conversations and interactions with health care practitioners | Positive | Communication | Descriptions of open, honest, and regular conversations with HCPs using parent-friendly language | “be straightforward with us” “don’t hold back details” “call me daily” |

| Encouraged Infant Interactions | Encouragement to hold, feed, bathe infant by HCPs | “Hey, let me show you.” “they allowed me to do that” | |||

| Reassurance | Reassured or consoled about her experience by HCPs | “reassured me that he’s okay” “This is normal. It happens.” | |||

| Negative | Disagreement about care | Concerns about medical or care-based decisions and actions | “one nurse that I don’t like” “can’t you see what’s going on with my child?” | ||

| Poor communication | Lack of updates, using jargoned language | “it was confusing” | |||

| Discouraged interactions | Limitations to mother in care activities due to actions or inactions of HCPs | “not initiated by the healthcare team” “they prefer that you’re able to stay” | |||

| Guilt or burdensome | Feeling of being a burden to the HCP, making infant situation worse | “wrong way” “I don’t belong here” | |||

| Shared Medical Decision-Making | Whether mother felt included in decision-making related to infant’s care | “they’ll explain it” “made sure that I understood” “what I say doesn’t matter” | |||

| Trustworthiness | Descriptions of characteristics that make a HCP trustworthy or not | Positive | Care for infant | HCP going above and beyond; examples of care and compassion | “show compassion” “call them by name” |

| Connection | Positive relationship between mother and HCP | “great connection” “talk as a friend” | |||

| Mutual Trust | HCP extends trust to mother and, in turn, mother trusts HCP | “engage yourself with parents” | |||

| Negative | “lose trust and confidence” “I don’t know” “kind of skeptical” | ||||

| Bias | Perceptions of biased interactions with HCPs | Race-related | Descriptions of perceived bias related to Black race | “cares so much about mothers” “really good and safe” | |

| Other | Descriptions of perceived bias based on other aspects of mom’s identity | “belittled me” “dirty looks” “won’t let you help out” | |||

| Emotions | Maternal descriptions of emotions towards infant, NICU setting, or HCPs | Positive | Generally positive emotions and/or expressions of gratitude towards infant, NICU setting, or HCPs | “so happy” “really touched my heart” “it really touched me” “just being closer… kiss them” “that’s a blessing” | |

| Negative | Negative emotions towards infant, NICU setting, or HCPs | “it’s scary” “you can’t do anything” “really nervous” “I was sad” | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCarty, D.B.; Ferrari, R.M.; Golden, S.; Zvara, B.J.; Wilson, W.D.; Shanahan, M.E. Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation. Children 2024, 11, 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111390

McCarty DB, Ferrari RM, Golden S, Zvara BJ, Wilson WD, Shanahan ME. Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation. Children. 2024; 11(11):1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111390

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarty, Dana B., Renée M. Ferrari, Shelley Golden, Bharathi J. Zvara, Wylin D. Wilson, and Meghan E. Shanahan. 2024. "Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation" Children 11, no. 11: 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111390

APA StyleMcCarty, D. B., Ferrari, R. M., Golden, S., Zvara, B. J., Wilson, W. D., & Shanahan, M. E. (2024). Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation. Children, 11(11), 1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111390