Hasn’t Child Abuse Been Overlooked? An Evaluation of Abused Children Who Visited the Emergency Department with Sentinel Injuries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Operational Definition of Sentinel Injuries

2.3. Variables

2.4. Association Between Diagnostic Test and Type of Sentinel Injury

2.5. Association Between the Diagnostic Test and the Level of the Emergency Center

2.6. Statistical Analysis

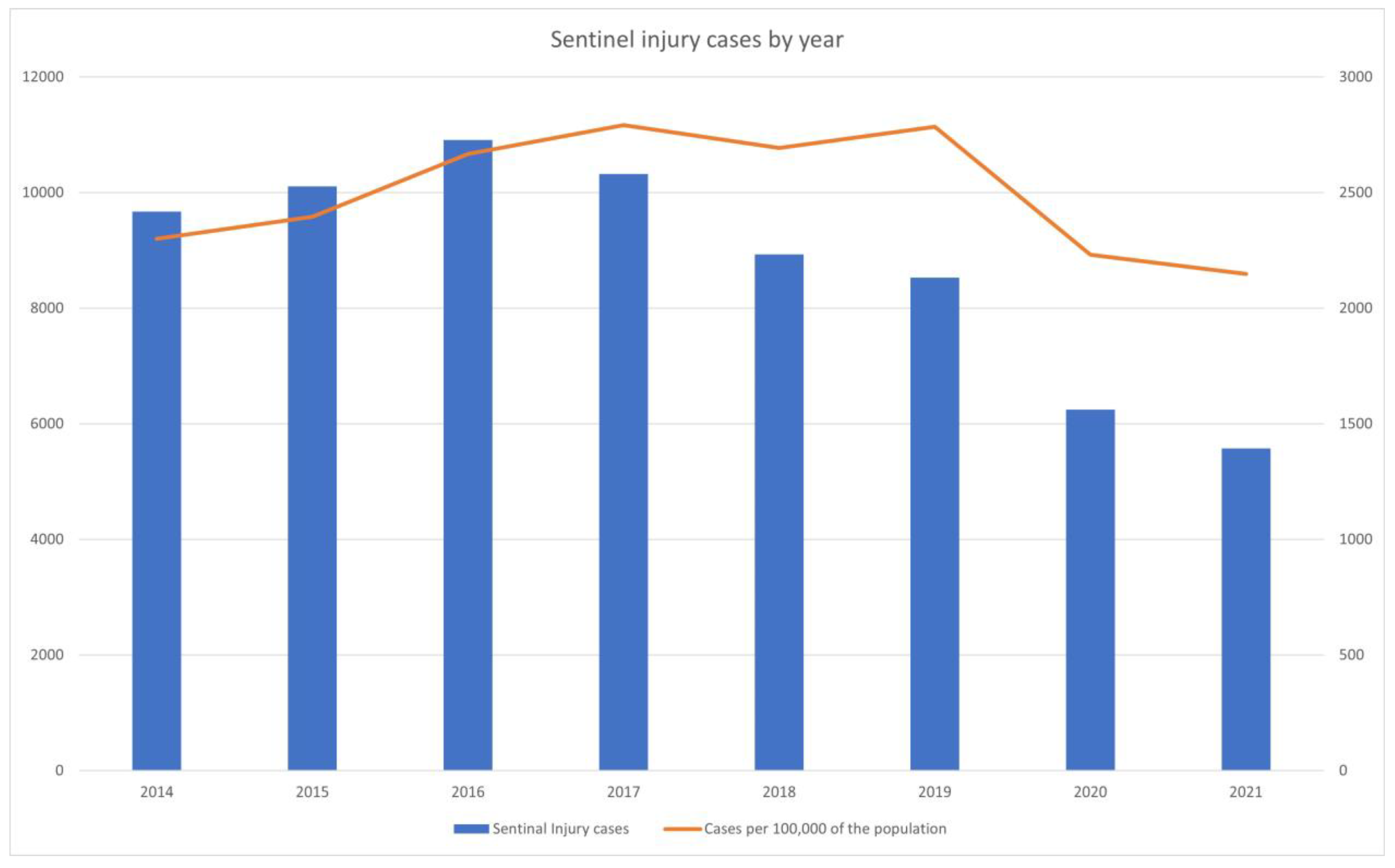

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wegman, H.L.; Stetler, C. A Meta-Analytic Review of the Effects of Childhood Abuse on Medical Outcomes in Adulthood. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 805–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, H.M.; Letson, M.M.; Spencer, S.P.; Dolan, K.; Foster, J.; Crichton, K.G. Recognizing Nonaccidental Trauma in a Pediatric Tertiary Hospital: A Quality Improvement Imperative. Pediatr. Qual. Saf. 2023, 8, e644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.L.; Yilanli, M.; Rabbitt, A.L. Child Physical Abuse and Neglect. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. 2021 Annual Report on Child Abuse; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Huerta, C.T.; Perez, E.A.; Quiroz, H.; Quinn, K.; Thorson, C.M.; Hogan, A.R.; Brady, A.-C.; Sola, J.E. National burden of pediatric abusive injuries: Patterns vary by age. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2022, 38, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluke, J.D.; Tonmyr, L.; Gray, J.; Bettencourt Rodrigues, L.; Bolter, F.; Cash, S.; Jud, A.; Meinck, F.; Casas Muñoz, A.; O’Donnell, M.; et al. Child maltreatment data: A summary of progress, prospects and challenges. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Child Abuse and Neglect Korea 2023. Available online: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10411010100&bid=0019&act=view&list_no=1482961&tag=&nPage=1 (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Administration for Children & Families. Child Maltreatment. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/child-maltreatment (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Autraslian Institute of Health and Welfare. Child protection Australia 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-insights/contents/insights/the-process-of-determining-child-maltreatment (accessed on 13 November 2024).

- Mathews, B.; Pacella, R.; Scott, J.G.; Finkelhor, D.; Meinck, F.; Higgins, D.J.; Erskine, H.E.; Thomas, H.J.; Lawrence, D.M.; Haslam, D.M.; et al. The prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia: Findings from a national survey. Med. J. Aust. 2023, 218, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.B.; Noh, H. Defining Sentinel Injuries of Suspected Child Abuse by Age Using International Classification of Diseases-10: A Delphi Study. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2023, 39, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheets, L.K.; Leach, M.E.; Koszewski, I.J.; Lessmeier, A.M.; Nugent, M.; Simpson, P. Sentinel injuries in infants evaluated for child physical abuse. Pediatrics 2013, 131, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Ro, Y.S.; Kwon, H.; Suh, D.; Moon, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Care Utilization and Outcomes in Pediatric Patients with Intussusception. Children 2022, 9, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.K.; Paik, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Kang, S. Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Emergency Care Utilization in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Nationwide Population-based Study. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Kang, M.W.; Paek, S.H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department utilization patterns in South Korea: A retrospective observational study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, K.J.; Fliss, M.D.; Marshall, S.W.; Peticolas, K.; Proescholdbell, S.K.; Waller, A.E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of emergency department services for the treatment of injuries. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 47, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, J.H.; Paek, S.H.; Kim, T.; Kim, S.; Ko, E.; Ro, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Kwon, J.H. Characteristics of pediatric emergency department visits before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A report from the National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) of Korea, 2018–2022. Clin. Exp. Emerg. Med. 2023, 10, S13–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbourne, C.; Cole, E.; Marsh, S.; Rex, D.; Makin, E.; Salter, R.; Brohi, K.; Edmonds, N.; Cleeve, S.; O’Neill, B.; et al. At risk child: A contemporary analysis of injured children in London and the South East of England: A prospective, multicentre cohort study. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyming, T.; Knudsen-Robbins, C.; Sharma, S.; Thackeray, J.; Schomberg, J.; Lara, B.; Wickens, M.; Wong, D. Child physical abuse screening in a pediatric ED.; Does TRAIN(ing) Help? BMC Pediatr. 2023, 23, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sim, S.-J. Quality of Life Indicators in Korea 2022; Statistics Korea. 2023, p. 106. Available online: https://sri.kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a90401000000&bid=11477&list_no=423793&act=view&mainXml=Y (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Team, U. How Many Children Are Victims of Abuse or Neglect in the US? Available online: https://usafacts.org/articles/how-many-children-are-victims-of-abuse-or-neglect-in-the-us/ (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Lindberg, D.M.; Beaty, B.; Juarez-Colunga, E.; Wood, J.N.; Runyan, D.K. Testing for Abuse in Children with Sentinel Injuries. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandiran, N.; Schuh, S.; Bejuk, M.; Al-Harthy, N.; Shouldice, M.; Au, H.; Boutis, K. Delayed identification of pediatric abuse-related fractures. Pediatrics 2010, 125, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.N.; Feudtner, C.; Medina, S.P.; Luan, X.; Localio, R.; Rubin, D.M. Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US children’s hospitals. Pediatrics 2012, 130, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paek, S.H.; Kwak, Y.H.; Noh, H.; Jung, J.H. A survey on the perception and attitude change of first-line healthcare providers after child abuse education in South Korea: A pilot study. Medicine 2019, 98, e14085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trokel, M.; Waddimba, A.; Griffith, J.; Sege, R. Variation in the diagnosis of child abuse in severely injured infants. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Sentinel Injury (N = 124,076) | Sentinel Injury (N = 61,989) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 65,939 (53.1%) | 35,133 (56.7%) | <0.01 |

| Diagnostic test | 54,634 (44.0%) | 22,711 (36.6%) | <0.01 |

| Skeletal survey | 21 (0.0%) | 5 (0.0%) | 0.19 |

| Any X-ray survey | 45,307 (36.5%) | 19,216 (31.0%) | <0.01 |

| Emergency center level | <0.01 | ||

| Regional emergency center | 41,080 (33.1%) | 20,511 (33.1%) | |

| Local emergency center | 77,666 (62.6%) | 38,466 (62.1%) | |

| Local emergency institution | 5079 (4.1%) | 2487 (4.0%) | |

| Other | 251 (0.2%) | 525 (0.8%) | |

| Intention | <0.01 | ||

| Accidental, unintentional | 117,241 (97.1%) | 59,278 (98.4%) | |

| Intentional self-harm | 5 (0.0%) | 1 (0.0%) | |

| Violence, assault | 156 (0.1%) | 76 (0.1%) | |

| Other specified | 1275 (1.1%) | 114 (0.2%) | |

| Unspecified | 2099 (1.7%) | 784 (1.3%) | |

| Mechanism of injury | <0.01 | ||

| Fall | 40,430 (33.5%) | 20,585 (34.2%) | |

| Slipped down | 7561 (6.3%) | 5970 (9.9%) | |

| Struck by person or object | 18,342 (15.2%) | 15,927 (26.4%) | |

| Cut or pierced | 5399 (4.5%) | 4997 (8.3%) | |

| Machine | 118 (0.1%) | 67 (0.1%) | |

| Fire, flames, or heat | 9425 (7.8%) | 8343 (13.8%) | |

| Drowning or nearly drowning | 249 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Poisoning | 3426 (2.8%) | 14 (0.0%) | |

| Choking | 516 (0.4%) | 8 (0.0%) | |

| Other (sexual assault, electric shock) | 31,760 (26.3%) | 3181 (5.3%) | |

| Unknown | 3550 (2.9%) | 1161 (1.9%) | |

| Route of arrival | <0.01 | ||

| Direct visit | 117,685 (94.8%) | 59,531 (96.0%) | |

| Transfer from other hospital | 6002 (4.8%) | 2341 (3.8%) | |

| Transfer from outpatient facility | 334 (0.3%) | 103 (0.2%) | |

| Other/unknown | 55 (0.1%) | 14 (0.0%) | |

| Korean Triage and Acuity Scale | <0.01 | ||

| 1 | 179 (0.2%) | 11 (0.0%) | |

| 2 | 2986 (3.3%) | 1321 (2.9%) | |

| 3 | 12,775 (14.1%) | 4919 (10.9%) | |

| 4 | 63,729 (70.3%) | 33,623 (74.3%) | |

| 5 | 10,903 (12.0%) | 5378 (11.9%) | |

| Other/unknown | 32 (0.0%) | 10 (0.0%) | |

| Specialist consultation | <0.01 | ||

| No | 47,513 (38.3%) | 24,450 (39.4%) | |

| Yes | 36,612 (29.5%) | 17,530 (28.3%) | |

| Other/unknown | 39,951 (32.2%) | 20,009 (32.3%) | |

| Length of stay, minutes | 47.0 (25.0–94.0) | 44.0 (24.0–86.0) | <0.01 |

| Dispositions | <0.01 | ||

| Discharge | 118,292 (95.6%) | 61,117 (98.7%) | |

| Transfer to other hospital | 733 (0.6%) | 215 (0.3%) | |

| Admission | 4592 (3.7%) | 584 (0.9%) | |

| Expired | 108 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Bruise (N = 33,836) | Burn (N = 11,926) | Open Wound (N = 21,729) | Human Bite or Subconjunctival Hemorrhage (N = 120) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic test | 17,898 (58.2%) | 345 (3.7%) | 4452 (20.5%) | 16 (13.3%) | |

| Any X-ray survey | 15,097 (49.1%) | 329 (3.5%) | 3786 (17.4%) | 4 (3.3%) | <0.01 |

| Brain imaging | 4200 (13.7%) | 4 (0.0%) | 351 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.01 |

| ALT/AST | 52 (0.2%) | 35 (0.4%) | 27 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | <0.01 |

| Fundus exam | 71 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 162 (0.7%) | 13 (10.8%) | <0.01 |

| Regional Emergency Center (N = 20,511) | Local Emergency Center (N = 38,466) | Local Emergency Institution (N = 2487) | Others (N = 525) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic test | 7430 (36.2%) | 14,674 (38.1%) | 497 (20.0%) | 110 (21.0%) | <0.01 |

| Skeletal survey | 1 (0.0%) | 4 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.86 |

| Any X-ray survey | 6454 (31.5%) | 12,281 (31.9%) | 376 (15.1%) | 105 (20.0%) | <0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, H.B.; Noh, H. Hasn’t Child Abuse Been Overlooked? An Evaluation of Abused Children Who Visited the Emergency Department with Sentinel Injuries. Children 2024, 11, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111389

Kim HB, Noh H. Hasn’t Child Abuse Been Overlooked? An Evaluation of Abused Children Who Visited the Emergency Department with Sentinel Injuries. Children. 2024; 11(11):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111389

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Han Bit, and Hyun Noh. 2024. "Hasn’t Child Abuse Been Overlooked? An Evaluation of Abused Children Who Visited the Emergency Department with Sentinel Injuries" Children 11, no. 11: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111389

APA StyleKim, H. B., & Noh, H. (2024). Hasn’t Child Abuse Been Overlooked? An Evaluation of Abused Children Who Visited the Emergency Department with Sentinel Injuries. Children, 11(11), 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111389