Abstract

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) provide structured information on the patient’s health experience and facilitate shared clinical decision-making. Registries that collect PROMs generate essential information about the clinical course and efficacy of interventions. Whilst PROMs are increasingly being used in adult orthopaedic registries, their use in paediatric orthopaedic registries is not well known. The purpose of this systematic review was to identify the frequency and scope of registries that collect PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic patient groups. In July 2023, six databases were systematically searched to identify studies that collected PROMs using a registry amongst patients aged under 18 years with orthopaedic diagnoses. Of 3190 identified articles, 128 unique registries were identified. Three were exclusively paediatric, 27 were majority paediatric, and the remainder included a minority of paediatric patients. One hundred and twenty-eight registries collected 72 different PROMs, and 58% of these PROMs were not validated for a paediatric population. The largest group of orthopaedic registries collected PROMs on knee ligament injuries (21%). There are few reported dedicated orthopaedic registries collecting PROMs in paediatric populations. The majority of PROMs collected amongst paediatric populations by orthopaedic registries are not validated for patients under the age of 18 years. The use of non-validated PROMs by registries greatly impedes their utility and impact. Dedicated orthopaedic registries collecting paediatric-validated PROMs are needed to increase health knowledge, improve decision-making between patients and healthcare providers, and optimise orthopaedic management.

1. Introduction

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are tools that are designed to assess a patient’s perception of their health-related quality of life and their functional health status without interpretation from a medical professional [1,2]. Self-assessment, by means of a questionnaire, is considered the best method of evaluating patient-based outcomes, as any influence from a clinician or investigator is removed [2]. By assessing a patient’s subjective health experience and the consequence of any intervention [2], PROMs are an essential tool to understand the impact a condition has on an individual’s symptoms and disability [3]. PROMs are vital to shared clinical decision-making and patient-centred care as they provide key information regarding the natural history of conditions and the efficacy of interventions that can assist all healthcare stakeholders (patients, healthcare professionals/providers, and policymakers) facing healthcare decisions [4]. The broad utility and high importance of PROMs are reflected in their widespread adoption and standardised use amongst regulatory bodies, such as the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, both of which mandate the use of PROMs to support labelling claims [5,6]. The use of PROMs has increased substantially in the field of orthopaedics over the last 20 years as the evidence for their importance has grown [1]. Since 2009, it has been mandatory to use PROMs to report outcomes for certain elective surgeries in the United Kingdom. The National Health Service publishes data from PROMs following orthopaedic surgical procedures to help drive improvements in surgical performance and service delivery [7].

Evidence of the increased use of PROMs is seen in the growing number of orthopaedic registries that have adopted PROMs [1]. Registries were first established in the fields of arthroplasty and trauma to monitor implant survival [1]. However, in recent decades, the utility of registries has been demonstrated by understanding patient characteristics, improving the timing and safety of intervention, and optimising public health decision-making [8]. If registries are large enough and include an adequate follow-up, they can provide an ideal platform for clinical trials, reducing resources required for prospective data collection [9]. Registry data can also be used to assist in answering questions that are not practical or ethical to address by randomised controlled trials [10]. By tracking health outcomes over time, it is possible to identify the under-utilisation of evidence-based practices and areas for improvement [11]. There is strong evidence that registry information can drive continuous improvements in patient outcomes and adherence to guideline-recommended care [10]. Registries, however, cannot achieve these goals without the inclusion of PROMs [8]. For example, in arthroplasty registries, the use of PROMs is now considered essential to determine a valid understanding of treatment success. Similarly, the improved survival rate in trauma registries has highlighted the need to collect PROMs to measure quality of life after injury [12].

Despite the importance of PROMs, there is little consistency in the use of PROMs in paediatric orthopaedics, and their use is infrequent compared to adult orthopaedics [2,13]. Furthermore, where PROMs are used, they are commonly not validated for paediatric populations [13,14]. If PROMs are not valid in the assessed population, they cannot be relied upon to measure the true impact of an intervention or inform healthcare decisions [14]. The standardised use of validated PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic registries is an essential step towards improving clinical care in paediatric orthopaedics [13,15]. Whilst PROMs orthopaedic registries are utilised in adult populations to improve the safety and efficacy of healthcare, in addition to strengthening communication and understanding between patients and healthcare providers, little is known about the use of PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic registries.

To ensure that PROM collection in paediatric orthopaedic registries is valid and useful in improving clinical understanding and care, it is crucial to identify gaps and weaknesses in the current state of PROM collection. It is vital to establish the current state of PROM collection by paediatric orthopaedic registries in order to highlight the most pressing issues and challenges facing this field of research and guide the future creation of registries. The aim of this systematic review is to achieve this goal by identifying the frequency and scope of registries that collect PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic patient groups and highlighting factors that need to be addressed to improve their utility.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed following the guidelines for best practice in transparent, reproducible, and ethical reporting of systematic reviews (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis—PRISMA), and the protocol was registered (PROSPERO—CRD42021215364). Six electronic databases were searched from inception to 17 July 2023: Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, Cinahl, and Google Scholar. The search was developed with the assistance of an experienced librarian (KE) and tailored to each database using search terms that were a mix of database-controlled keywords, medical subject headings (MeSH), and the keywords p(a)ediatric, orthop(a)edic, registry and patient-reported outcome measures. The full search strategy is shown in Supplementary Text S1.

We included peer-reviewed, full-text, observational cohort, and case-control studies that included paediatric patients (<18 years), collected PROMs, had primary orthopaedic diagnoses, and included the use of a database or registry to collect PROMs. Patients were considered to have ‘primary orthopaedic diagnoses’ if the orthopaedic diagnosis was the primary reason for seeking treatment and if they were reviewed by an orthopaedic specialist. Studies were excluded if an English translation was unavailable, if they were limited to systematic reviews or published protocols, if they primarily focused on craniofacial orthopaedic diagnoses, or if they did not collect PROMs prospectively in the registry or database. Craniofacial diagnoses were excluded since they are included in the orthodontics and dentistry literature and not orthopaedics. Studies were grouped by the proportion of patients under the age of 18 years and according to their diagnostic inclusion.

After removing duplicates, two reviewers (EM, KG) independently screened titles and abstracts and five reviewers (EM, KG, JG, JS, AA) independently screened full-text studies against the inclusion criteria using Covidence software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia, 2023). Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved via discussion, with the support of a third review author (MM) if consensus was not reached. These discrepancies involved <9% of articles and were only related to the reason for exclusion. Of the studies included after full-text screening, each reference list was checked to identify other relevant studies for inclusion. No additional studies were identified using this method.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Using a standard form in Covidence, the data were extracted by one researcher (EM). The data extraction included: name of registry, scope of registry, country of registry, active years of registry, diagnostic criteria of included patients, age range of included patients, gender of included patients, PROMs used, time points of PROM collection, mode of PROM collection, sample size, type of study, nature of interventions examined, summary of findings of study, and how PROMs contributed to these findings. The scope was defined as ‘hospital’ if the registry collected data from a single hospital, ‘regional’ if the registry collected data from multiple hospitals, in a similar area, ‘national’ if a concerted effort was made to collect data from most, if not all, relevant hospitals/services in that country, and ‘international’ if data were collected from more than one country.

The risk of bias of all included studies was assessed using the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for cohort or case control studies, using Covidence software, by EM and KG. This scale was used because it was developed specifically for cohort and case control studies, which were the two types of studies that this systematic review identified. The criteria used by NOS to assess quality are provided in Supplementary Text S2. Studies with NOS scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 were considered as low, moderate, and high quality, respectively [16].

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

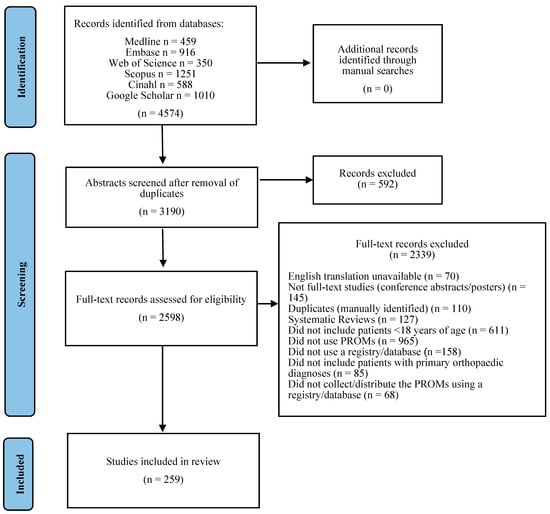

The process of screening is summarised in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). A total of 4383 studies were identified through the search strategy. After the automatised removal of duplicates, 3011 studies remained. The titles and abstracts of the 3011 studies were screened, with 467 excluded due to not meeting the inclusion criteria. The remaining 2544 studies were then assessed for full-text eligibility by application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Covidence software allows only a single reason for exclusion, however, some studies would be excluded for more than one reason. The exclusion reason was chosen according to the order displayed in Figure 1. Of the 2339 studies that were excluded, 965 did not use PROMs, 611 did not include patients under the age of 18 years, 145 were not full-text studies (conference abstracts or poster presentations), 158 did not use a registry or database, 127 were systematic reviews, 110 were duplicates that had not been previously identified, 85 did not include patients with primary orthopaedic diagnoses, 70 did not have an available English translation, and 68 did not collect PROMs prospectively using a registry or database. After this assessment, 259 (10%) full-text studies were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of study selection.

3.2. Description of Studies and Risk of Bias

Of the 259 included studies, the majority were observational cohort studies, with the exception of 91 case-control studies. The style and purpose of the studies differed greatly, as seen in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. The risk of bias score for all studies, using the NOS for cohort or case control studies, is provided in the final column of Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4. All studies achieved scores of high quality (7–9), with the exception of five studies, which were rated as moderate quality. Four studies scored 6 [17,18,19,20,21] and one study scored 5 [21]. These studies were considered to have a higher risk of bias due to inadequate follow-up and lack of comparability of the cohort. The remaining studies (98%) were rated as having a low risk of bias. Complete details of the risk of bias scores for all included studies are provided in Supplementary Text S2.

Table 1.

Registries reporting exclusively paediatric patients.

Table 2.

Registries reporting majority paediatric patients (>50%).

Table 3.

Registries reporting a minority of paediatric patients (33–50%).

Table 4.

Registries reporting a small minority of paediatric patients (<33%).

3.3. Type of PROMs

The registries used 72 different PROMs, including 24 generic, 8 hip pathology-specific, and 14 knee-pathology-specific (Table 5). Amongst these 72 PROMs, 42 (58%) did not include any paediatric validation, and 7 (10%) included validation limited to those 16 years and over. In the 3 exclusively paediatric registries, all PROMs used were validated for paediatric populations, and amongst the 27 majority paediatric registries, 61% of the PROMs used were validated for those under 18 years of age. Regarding PROM collection frequency, 21% of the registries collected PROMs as a one-off, and the remainder collected them at multiple time points. The three most common PROM collection time points were pre-surgery, one-year post-surgery, and two years post-surgery, however, there was great variation across all registries.

Table 5.

PROMs used among paediatric patients in orthopaedic registries.

3.4. Registries

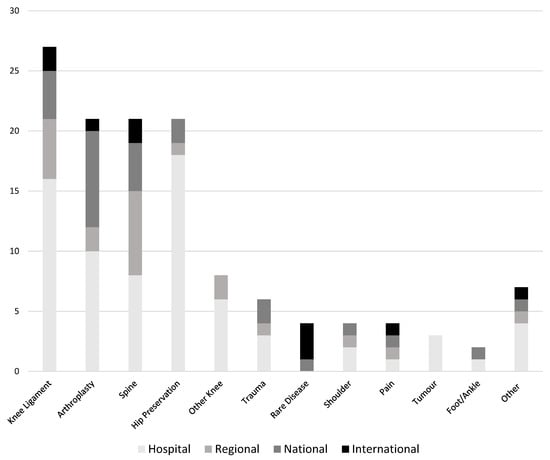

Overall, 128 unique registries that included patients under the age of 18 years in their reported data sets were identified. There were three registries that included exclusively paediatric patients (Table 1), 27 registries that included a majority (>50%) of paediatric patients (Table 2), 16 registries that included a minority (33–50%) of paediatric patients (Table 3), and 82 registries that included a small minority (<33%) of paediatric patients. (Table 4). There were 27 knee ligament registries, 21 arthroplasty registries, 21 spine registries, and 21 hip preservation registries (Table 6). The scope of registries ranged from single hospital-based to international, with 56% (n = 72) of all included registries limited to a single-hospital scope. We identified 21 regional registries, 25 national registries, and 10 international registries. (Figure 2).

Table 6.

Types of registries that include patients under the age of 18 years.

Figure 2.

Scope of registries that include patients under the age of 18 years.

3.4.1. Knee Ligament Registries

Of the 27 knee ligament registries that included patients under the age of 18 years, 16 were hospital-based registries, and 4 were national registries: the Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, and New Zealand Knee Ligament Registries [108,165,184,190]. One registry was a majority paediatric hospital-based registry that used only PROMs validated for those under 18 years (Pediatric–International Knee Documentation Committee (Pedi-IKDC) and Children’s Health Questionnaire(CHQ)) [29]. The remaining 26 registries were minority paediatric but had notably larger proportions of patients aged under 18 years compared to the arthroplasty registries (Table 6). These registries used 23 PROMs, including 11 generic PROMs and 12 knee-specific PROMs. The two most used knee-specific PROMs were the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), which is validated for those 16 years and over, and the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), which is not validated for paediatrics.

3.4.2. Lower Limb Arthroplasty Registries

The lower limb arthroplasty registries included a small minority of paediatric patients, with the exception of one [28]. Most were hip arthroplasty registries, of which two were national registries, with the majority being limited to a single-hospital scope [142,153]. There were three that included hip, knee, and ankle arthroplasties in one registry [143,145] There were nine anatomy-specific and eight generic PROMs used by these registries (Table 5). The most commonly used were the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), European Quality of Life—5 dimensions (EQ5D), and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), which were each used in four different registries. Of these, the WOMAC is not validated for paediatrics, the EQ5D is validated for those 16 years and over, and the VAS is validated for paediatric patients from the age of five years.

3.4.3. Spine Registries

There were 21 spine registries that included patients under the age of 18 years. Only 1 was exclusively paediatric [22], and a further 15 reported a majority of paediatric patients (Table 2). The most frequently used PROM was the Scoliosis Research Society Questionnaire (SRS) (various versions), which has been validated for the paediatric population from the age of 10 years. In both majority and minority paediatric registries, this PROM was occasionally used amongst participants younger than 10 years [22,84]. Other PROMs used and validated for paediatric patients included the Early-Onset Questionnaire (EOSQ24) and the Caregiver Priorities Child Health Index of Life with Disabilities (CPCHILD) [55,61]. Similar to the SRS, the Short Form 12 and 36 (SF12, SF36), the Body Image Disturbance Questionnaire (BIDQ), and the European Quality of Life 5 Dimensions 3 Levels (EQ5D3L) were all used in patients below the age of their paediatric validation range, and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) was used in spine registries despite not being validated for those under the age of 18 years [93,94,227].

3.4.4. Hip Preservation Registries

We identified 21 hip preservation registries that included patients under the age of 18 years. A total of 2 of these had a majority of paediatric patients [30], and 18 were hospital-based. These 21 registries used 11 PROMs, including 8 hip-specific PROMs. Of these, only the Hip Outcome Score (HOS) was validated for patients under 18 years and utilised in 5 of the 21 hip preservation registries (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

4. Discussion

This review highlights the paucity of PROM collection amongst paediatric patients by orthopaedic registries; specifically, only three dedicated paediatric registries collect PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic populations. There were an additional 125 orthopaedic registries that included both adults and paediatric patients, with 98 of these registries including a minority of individuals aged under 18 years. Of all studies reporting these registries, 98% were of high quality, with a low risk of bias. Registries that collect PROMs typically establish a structure for studies that avoids a number of risks associated with single studies, including bias in-patient selection, comparability of cohorts, prospective data collection, and duration of follow-up. Whilst these concerns are usually not an issue for a well-designed registry, the challenge of an adequate response rate, which was the NOQAS criterion most frequently not met by the studies in this review, can be a significant concern.

The importance of well-designed and well-maintained registries that minimise loss to follow-up has been widely established in adult populations [1]. Such high-quality registry data have resulted in improved models of care in a number of health specialties. Some examples include accelerated ulcer healing time, attributed to the Swedish Ulcer Registry [345], and established causes of mortality associated with rheumatoid arthritis [346]. Furthermore, diabetes registries have improved attendance at appointments and compliance with treatment regimens [347] and the Australian Breast Device Registry detected three devices with high complication rates, which were subsequently removed by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, resulting in reduced national revision rates [348]. Likewise, in orthopaedics, data from the Australian Joint Replacement Registry identified high revision rates associated with the ASR™ Hip Resurfacing System, leading to a substantial reduction in their use and an overall reduction in hip and knee arthroplasty revisions since the registry has been in operation [349]. The Victorian Orthopaedic Trauma Outcomes Registry identified key factors in demographics and injury management affecting return to work and mortality in those under 65 years who sustain a hip fracture [245,246].

The second largest proportion of registries identified in this review were arthroplasty registries that consistently use PROMs not validated for use in people aged under 18 years. Whilst the average age of patients undergoing arthroplasty was greater than 70 years in the early 1990s, in recent years, the average age has decreased, and future projections indicate that it will continue to do so [350]. In light of the historically older age, it is not surprising that arthroplasty registries were not established with paediatrics in mind [350]. However, given the documented increased frequency of paediatric arthroplasty [351,352,353], it is now essential that registries accommodate paediatric patients. The majority of the remaining orthopaedic registries identified in this review concern specific diagnostic groups such as knee ligament reconstruction, hip preservation procedures, spine surgery, and trauma. It is paramount that registries for these diagnostic groups collect validated PROMs for the age range of included children so that information gathered can be utilised to improve the clinical course of these conditions and gauge the efficacy of interventions [13].

One barrier to the inclusion of paediatric-validated PROMs in orthopaedic registries may be the limited number of appropriate PROMs available for specific diagnostic groups. Currently, the only hip-specific PROM with paediatric validation is the Hip Outcome Score, which is validated for those aged 13 years and over [305]. A systematic review of hip PROMs used in older paediatric patients did not comment on whether the PROMs used were validated for the reported age group [354]. Likewise, the lack of adequate PROMs is a significant challenge shared by rare disease diagnostic groups with orthopaedic involvement. The use of non-validated custom questionnaires by many of the rare disease registries highlights the inadequacy of existing validated PROMs for their purposes [21,101,102]. A lack of validated PROMs significantly reduces the extent to which orthopaedic registries can capture relevant and valid information to ultimately improve healthcare efficacy and safety [13,355].

This review shows that when paediatric-validated PROMs are available, they are rarely used by orthopaedic registries that include paediatric patients [356,357]. A challenge in using paediatric-validated PROMs in registries that include both adults and paediatric patients may be the increased burden of customising PROM delivery according to age [3]. This was apparent in the knee ligament registries, which overwhelmingly used the KOOS [112,172] and/or the IKDC [119,358], and not the KOOS-child, validated from 16 years of age, or the Pedi-IKDC, which is validated and recommended for those under 18 years of age [315,359]. Improved registry design to collect valid data from all patients that can be utilised to understand the natural history and surgical outcomes from childhood through to adulthood is required. The burden of integrating paeditric and adult versions of a PROM in the same registry can be overcome with digital platforms, such as research electronic data capture (REDCap) [360], which can automatically distribute age-appropriate validated PROMs.

Another possible reason for registries not using validated paediatric PROMs when available may be the challenge of comparing scores between paediatric and adult-version PROMs [3]. This again can be overcome by using paediatric and adult versions of the same PROM that have published equivalency scores [359]. By doing so, such registries would improve the understanding of orthopaedic conditions, and the impact of interventions as paediatric patients transition into adulthood. The integration of scores between two different PROMs remains a substantial challenge. Further research to establish the clinical and statistical relationship between the most appropriate paediatric and adult PROM will only be possible if appropriate validated PROMs are used in these registries.

The findings of this review point to two key actions that can be undertaken to improve PROM collection by orthopaedic registries. Firstly, for adult registries that include participants under the age of 18 years, accommodations must be made for these younger participants to ensure the data that are collected are valid and useful. Secondly, there is a need for further dedicated paediatric orthopaedic registries that collect PROMs in order to answer future questions concerning paediatric orthopaedic conditions and interventions. Such actions may be accelerated if policies are introduced by health services that require more uniform PROM collection amongst orthopaedic populations such as has been seen in arthroplasty registries [4]. Furthermore, insistence on the use of validated PROMs by journals would result in registries no longer using non-validated tools. These changes have the potential to transform the scope and quality of paediatric orthopaedic research. Such improvements would increase the understanding of how orthopaedic conditions affect children and raise the standard of care provided to such children.

We acknowledge the limitations of this review. First, our search criteria included any registry that included patients under 18 years of age. This resulted in a large number of registries that included a very small proportion of paediatric patients, including a number of registries that included one or two 17-year-olds. However, we attempted to make this issue transparent by grouping the registries by the proportion of paediatric patients they included (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4). Second, the exclusion of craniofacial orthopaedic diagnoses was undertaken due to a large overlap with dental medicine publications, as these were considered too far removed from the common understanding of paediatric orthopaedics. Further reviews examining the relevance of these articles may be indicated. Third, we acknowledge there may be registries in existence that collect validated PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic populations but have not yet published their findings and were, therefore, not included in this systematic review.

5. Conclusions

Currently, there are only three reported registries with publications that have been established to collect PROMs in paediatric orthopaedic patients, though many adult orthopaedic registries include the collection of PROMs in paediatric patients. Comparing this small number to the frequency of adult orthopaedic registries highlights the paucity of paediatric orthopaedic registries that collect PROMs. Given that these three registries report data collected since 2000, it is apparent that this is an area of clinical research that has been slow to change. The lack of systematic collection of validated PROMs in paediatric orthopaedics through registries means that the paediatric orthopaedic literature is largely dependent on clinician-reported outcomes and individual studies. This reduces the understanding of conditions and treatment impact from the perspective of the patient. As a result, the research findings may be limited by patient numbers and a narrower scope of investigated questions. In contrast, registries that collect PROMs provide essential information about the course of clinical conditions and interventions from the patient’s perspective, ultimately promoting patient-centred care and shared decision-making. Therefore, if we are to better understand health conditions, assess interventions and improve the quality and safety of care in paediatric orthopaedics, registries must be established and must use validated PROMs in their target populations. An investment in infrastructure to support the collection of PROMs by registries in paediatric orthopaedics is needed from health service providers and policymakers. Such changes will allow health outcomes to be assessed in children and tracked as children grow into adults.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children10091552/s1, Text S1: Complete Search Strategy; Text S2: Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Form for Cohort Studies & Case-Control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.M., P.J.G., J.B. and M.J.M.; methodology, E.J.M., K.G., P.J.G., J.B. and M.J.M.; data collection, E.J.M., K.G., J.G., J.S., A.B.A. and M.J.M.; analysis, E.J.M., K.G., J.G., J.S., A.B.A., M.J.M., P.J.G. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.M. and M.J.M.; writing—review and editing, E.J.M., K.G., J.G., J.S., A.B.A., M.J.M., P.J.G. and J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

A systematic review protocol was made and registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The protocol can be accessed at: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021215364 (accessed on 13 August 2023).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Kanchana Ekanayake, University of Sydney librarian, who assisted with the development of the search strategy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wilson, I.; Bohm, E.; Lübbeke, A.; Lyman, S.; Overgaard, S.; Rolfson, O.; W-Dahl, A.; Wilkinson, M.; Dunbar, M. Orthopaedic registries with patient-reported outcome measures. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, L.; Carsen, S.; Vasireddi, A.; Mulpuri, K. Use of Patient-reported Outcome Measures in Pediatric Orthopaedic Literature. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2018, 38, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleischmann, M.; Vaughan, B. The challenges and opportunities of using patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) in clinical practice. Int. J. Osteopat. Med. 2018, 28, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfson, O.; Bohm, E.; Franklin, P.; Lyman, S.; Denissen, G.; Dawson, J.; Dunn, J.; Chenok, K.E.; Dunbar, M.; Overgaard, S.; et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in arthroplasty registries. Report of the Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Working Group of the International Society of Arthroplasty Registries Part II. Recommendations for selection, administration, and analysis. Acta Orthop. 2016, 87, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims: Draft guidance. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyte, D.; Reeve, B.B.; Efficace, F.; Haywood, K.; Mercieca-Bebber, R.; King, M.T.; Norquist, J.M.; Lenderking, W.R.; Snyder, C.; Ring, L.; et al. International Society for Quality of Life Research commentary on the draft European Medicines Agency reflection paper on the use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies. Qual. Life Res. 2016, 25, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldring, T.; Smith, S.M. Article Commentary: Patient-Reported Outcomes (PROs) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs). Health Serv. Insights 2013, 6, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lübbeke, A.; Silman, A.J.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Adler, A.I.; Barea, C.; Carr, A.J. The role of national registries in improving patient safety for hip and knee replacements. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, H.T. Regional administrative health registries as a resource in clinical epidemiology—A study of options, strengths, limitations and data quality provided with examples of use. Int. J. Risk Saf. Med. 1997, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, D.M.E.; Kumari, V.; Hoque, M.; Ruseckaite, R.; Romero, L.; Evans, S.M. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, K.; Bertrand, D.P.; Rault, G. Using registry data to improve quality of care. J. Cyst. Fibros. 2018, 17, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, G.M.; Slade, A.; Retzer, A.; McMullan, C.; Kyte, D.; Belli, A.; Calvert, M. An introduction to patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) in trauma. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2019, 86, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arguelles, G.R.B.; Shin, M.B.; Lebrun, D.G.; Kocher, M.S.; Baldwin, K.D.M.; Patel, N.M.M. The Majority of Patient-reported Outcome Measures in Pediatric Orthopaedic Research Are Used without Validation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2021, 41, E74–E79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, W.H.; Price, M.J.; Agarwal, K.N.; Suryavanshi, J.R.; Somasegar, S.; Thompson, M.; Fabricant, P.D.; Dodwell, E.R. Utilization of a Wide Array of Nonvalidated Outcome Scales in Pediatric Orthopaedic Publications: Can’t We All Measure the Same Thing? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e153–e158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viehweger, E.; Jouve, J.-L.; Simeoni, M.-C. Outcome evaluation in pediatric orthopedics. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2014, 100, S113–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.; Marks, M.C.; Yaszay, B.; Newton, P.O. Postoperative Perfection: Ceiling Effects and Lack of Discrimination with Both SRS-22 and -24 Outcomes Instruments in Patients with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2015, 40, E1323–E1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojcic, J.L.; Sue, V.M.; Huon, T.S.; Maletis, G.B.; Inacio, M.C. Comparison of Paper and Electronic Surveys for Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Perm. J. 2014, 18, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, F.; Day, R.; Haigh, C.; Gill, S.; Nightingale, J.; O’Neill, O.; Counsell, D. First Steps Toward Understanding the Variability in Acute Pain Service Provision and the Quality of Pain Relief in Everyday Practice across the United Kingdom. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ryu, S.; Richardson, R.; Cady, A.C.; Reeves, A.; Casanova, M.P.; Baker, R.T. Rasch Calibration of the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form. J. Sport Rehabil. 2023, 32, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belter, L.; Jarecki, J.; Reyna, S.P.; Cruz, R.; Jones, C.C.; Schroth, M.; O’Toole, C.M.; O’brien, S.; Hall, S.A.; Johnson, N.B.; et al. The Cure SMA Membership Surveys: Highlights of Key Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Individuals with Spinal Muscular Atrophy. J. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2021, 8, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, C.; Talwar, D.; Gordon, J.; Capraro, A.; Lott, C.; Cahill, P.J. Patient-Reported Outcomes Are Equivalent in Patients Who Receive Vertebral Body Tethering versus Posterior Spinal Fusion in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Orthopedics 2020, 44, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messner, J.; Harwood, P.; Johnson, L.; Itte, V.; Bourke, G.; Foster, P. Lower limb paediatric trauma with bone and soft tissue loss: Ortho-plastic management and outcome in a major trauma centre. Injury 2020, 51, 1576–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, D.S.; Canizares, M.F.; Miller, P.E.; Waters, P.M.; Goldfarb, C.A. Functional Impact of Congenital Hand Differences: Early Results from the Congenital Upper Limb Differences (CoULD) Registry. J. Hand Surg. 2018, 43, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daley, E.; Peek, K.; Carlin, K.; Samora, J.; Vuillermin, C.; Wall, L.; Steinman, S.; Bae, D.; Bauer, A.; Waters, P.; et al. Effect of Race and Geography on Patient- and Parent-Reported Quality of Life for Children with Congenital Upper Limb Differences. J. Hand Surg. 2023, 48, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, L.B.; Wright, M.; Samora, J.; Bae, D.S.; Steinman, S.; Goldfarb, C.A. Social Deprivation and Congenital Upper Extremity Differences—An Assessment Using PROMIS. J. Hand Surg. 2021, 46, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, L.B.; Velicki, K.; Morris, M.; Roberts, S.; Goldfarb, C.A. The Effect of Adoption on Functioning and Psychosocial Well-Being in Patients with Congenital Upper-Extremity Differences. J. Hand Surg. 2021, 46, 856–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallante, G.D.; Statz, J.M.; Milbrandt, T.A.; Trousdale, R.T. Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty in Patients 20 Years Old and Younger. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2020, 102, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boykin, R.E.; McFeely, E.D.; Shearer, D.; Frank, J.S.; Harrod, C.C.; Nasreddine, A.Y.; Kocher, M.S. Correlation Between the Child Health Questionnaire and the International Knee Documentation Committee Score in Pediatric and Adolescent Patients with an Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tear. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2013, 33, 216–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Chang, B.; Kahlenberg, C.A.; Fields, K.; Nawabi, D.H.; Kelly, B.T.; Ranawat, A.S. Arthroscopic Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement in Adolescents Provides Clinically Significant Outcome Improvement. Arthroscopy 2017, 33, 1812–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serbin, P.A.; Youngman, T.R.; Johnson, B.L.; Wilson, P.L.; Sucato, D.; Podeszwa, D.; Ellis, H.B. Radiographic Predictors of Reoperation in Adolescents Undergoing Hip Preservation Surgery for Femoroacetabular Impingement. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastrom, T.P.; Howard, R.; Bartley, C.E.; Newton, P.O.; Lenke, L.G.; Sponseller, P.D.; Shufflebarger, H.; Lonner, B.; Shah, S.A.; Betz, R.; et al. Are patients who return for 10-year follow-up after AIS surgery different from those who do not? Spine Deform. 2022, 10, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.E.; Newton, P.O. Patient-Reported SRS-24 Outcomes Scores after Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Have Improved Since the New Millennium. Spine Deform. 2019, 7, 917–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastrom, T.P.; Marks, M.C.; Yaszay, B.; Newton, P.O. Prevalence of Postoperative Pain in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis and the Association with Preoperative Pain. Spine 2013, 38, 1848–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benes, G.B.; Shufflebarger, H.L.; Shah, S.A.; Yaszay, B.; Marks, M.C.; Newton, P.O.; Sponseller, P.D.M. Late Infection after Spinal Fusion for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Implant Exchange versus Removal. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2023, 43, e525–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.T.; Hoashi, J.S.; Ames, R.J.; Kimball, J.S.; Pahys, J.M.; Samdani, A.F. The posterior pedicle screw construct: 5-year results for thoracolumbar and lumbar curves. J. Neurosurg. Spine 2013, 19, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.T.; Samdani, A.F.; Bastrom, T.P.; Ames, R.J.; Miyanji, F.; Pahys, J.M.; Marks, M.C.; Lonner, B.S.; Newton, P.O.; Shufflebarger, H.L.; et al. Factors affecting the outcome in appearance of AIS surgery in terms of the minimal clinically important difference. Eur. Spine J. 2017, 26, 1782–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckland, A.J.; Moon, J.Y.; Betz, R.R.; Lonner, B.S.; Newton, P.O.; Shufflebarger, H.L.; Errico, T.J. Ponte Osteotomies Increase the Risk of Neuromonitoring Alerts in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Correction Surgery. Spine 2019, 44, E175–E180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.; Yaszay, B.; Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.E.; Parent, S.; Cahill, P.J.; Lonner, B.; Shah, S.A.; Samdani, A.; Newton, P.O. Long-term Patient Perception Following Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis if Dissatisfied at 2-year Follow-up. Spine 2021, 46, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sponseller, P.D.; Negrini, S.; Newton, P.O.; Cahill, P.J.; Bastrom, T.P.; Marks, M.C. SRS-7: A Valid, Responsive, Linear, and Unidimensional Functional Outcome Measure for Operatively Treated Patients with AIS. Spine 2015, 40, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.P.; Lenke, L.G.; Sponseller, P.D.; Pahys, J.M.; Bastrom, T.P.; Lonner, B.S.; Abel, M.F. The minimum detectable measurement difference for the Scoliosis Research Society-22r in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A comparison with the minimum clinically important difference. Spine J. 2019, 19, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lark, R.K.; Yaszay, B.; Bastrom, T.P.; Newton, P.O. Adding Thoracic Fusion Levels in Lenke 5 Curves: Risks and benefits. Spine 2013, 38, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonner, B.; Yoo, A.; Terran, J.S.; Sponseller, P.; Samdani, A.; Betz, R.; Shuffelbarger, H.; Shah, S.A.; Newton, P. Effect of Spinal Deformity on Adolescent Quality of Life: Comparison of Operative Scheuermann Kyphosis, Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis, and Normal Controls. Spine 2013, 38, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louer, C.; Yaszay, B.; Cross, M.; Bartley, C.E.; Bastrom, T.P.; Shah, S.A.; Lonner, B.; Cahill, P.J.; Samdani, A.; Upasani, V.V.; et al. Ten-Year Outcomes of Selective Fusions for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2019, 101, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.O.; Ohashi, M.; Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.E.; Yaszay, B.; Marks, M.C.; Betz, R.; Lenke, L.G.; Clements, D. Prospective 10-year follow-up assessment of spinal fusions for thoracic AIS: Radiographic and clinical outcomes. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, P.O.; Parent, S.; Miyanji, F.; Alanay, A.; Lonner, B.S.; Neal, K.M.; Hoernschemeyer, D.G.; Yaszay, B.; Blakemore, L.C.; Shah, S.A.; et al. Anterior Vertebral Body Tethering Compared with Posterior Spinal Fusion for Major Thoracic Curves: A Retrospective: Comparison by the Harms Study Group. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022, 104, 2170–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohashi, M.; Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.E.; Yaszay, B.; Upasani, V.V.; Newton, P.O.; Buckland, A.; Samdani, A.; Jain, A.; Lonner, B.; et al. Associations between three-dimensional measurements of the spinal deformity and preoperative SRS-22 scores in patients undergoing surgery for major thoracic adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, L.; Yaszay, B.; Bastrom, T.P.; Shah, S.A.; Lonner, B.S.; Miyanji, F.; Samdani, A.F.; Parent, S.; Asghar, J.; Cahill, P.J.; et al. L3 translation predicts when L3 is not distal enough for an “ideal” result in Lenke 5 curves. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.; Asghar, J.; Bastrom, T.; Shufflebarger, H.; Newton, P.O.; Sturm, P.; Betz, R.R.; Samdani, A.F.; Yaszay, B. Optimal Radiographical Criteria after Selective Thoracic Fusion for Patients with Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis with a C Lumbar Modifier: Does adherence to current guidelines predict success? Spine 2014, 39, E1368–E1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, D.N.; Harms Study Group; Grabel, Z.J.; Konopka, J.A.; Boissonneault, A.R.; Yoon, E.; Bastrom, T.P.; Flynn, J.M.; Fletcher, N.D. Fusions ending at the thoracolumbar junction in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: Comparison of lower instrumented vertebrae. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, A.; Bennett, J.T.; Sponseller, P.D.; Pahys, J.M.; Marks, M.C.; Lonner, B.S.; Newton, P.O.; Miyanji, F.; Betz, R.R.; Cahill, P.J.; et al. Results of Selective Thoracic Versus Nonselective Fusion in Lenke Type 3 Curves. Spine 2014, 39, 2034–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, L.E.; Upasani, V.V.; Pahys, J.M.; Fletcher, N.D.; George, S.G.; Shah, S.A.; Bastrom, T.P.; Bartley, C.E.; Lenke, L.G.; Newton, P.O.; et al. SRS-22r Self-Image after Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis at 10-year Follow-up. Spine 2023, 48, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upasani, V.V.; Caltoum, C.; Petcharaporn, M.; Bastrom, T.P.; Pawelek, J.B.; Betz, R.R.; Clements, D.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Lowe, T.G.; Newton, P.O. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Patients Report Increased Pain at Five Years Compared with Two Years after Surgical Treatment. Spine 2008, 33, 1107–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badin, D.; Baldwin, K.D.; Cahill, P.J.; Spiegel, D.A.; Shah, S.A.; Yaszay, B.; Newton, P.O.; Sponseller, P.D. When to Perform Fusion Short of the Pelvis in Patients with Cerebral Palsy?: Indications and Outcomes. JBJS Open Access 2023, 8, e22.00123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eguia, F.; Nhan, D.T.; Shah, S.A.; Jain, A.; Samdani, A.F.; Yaszay, B.; Pahys, J.M.; Marks, M.C.; Sponseller, P.D. Of Major Complication Types, Only Deep Infections after Spinal Fusion Are Associated with Worse Health-related Outcomes in Children with Cerebral Palsy. Spine 2020, 45, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, A.; Sullivan, B.T.B.; Shah, S.A.; Samdani, A.F.; Yaszay, B.; Marks, M.C.M.; Sponseller, P.D. Caregiver Perceptions and Health-Related Quality-of-Life Changes in Cerebral Palsy Patients after Spinal Arthrodesis. Spine 2018, 43, 1052–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.J.; Flynn, J.J.M.; Pasha, S.; Yaszay, B.; Parent, S.; Asghar, J.; Abel, M.F.; Pahys, J.M.; Samdani, A.; Hwang, S.W.; et al. Improving Health-related Quality of Life for Patients with Nonambulatory Cerebral Palsy: Who Stands to Gain from Scoliosis Surgery? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2020, 40, e186–e192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyanji, F.; Nasto, L.A.; Sponseller, P.D.; Shah, S.A.; Samdani, A.F.; Lonner, B.; Yaszay, B.; Clements, D.H.; Narayanan, U.; Newton, P.O. Assessing the Risk-Benefit Ratio of Scoliosis Surgery in Cerebral Palsy: Surgery Is Worth It. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2018, 100, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, A.C.; Harms Study Group; Pahys, J.M.; Jain, A.; Samdani, A.F.; Bastrom, T.P.; Sponseller, P.D.; Newton, P.O.; Hwang, S.W. Early and late hospital readmissions after spine deformity surgery in children with cerebral palsy. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J.M.; Yorgova, P.; Neiss, G.; Rogers, K.; Sturm, P.F.; Sponseller, P.D.; Luhmann, S.; Pawelek, J.B.; Shah, S.A. Early Onset Scoliosis: Is there an Improvement in Quality of Life with Conversion from Traditional Growing Rods to Magnetically Controlled Growing Rods? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2019, 39, e284–e288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Matsumoto, H.; Hilaire, T.S.; Roye, B.D.; Roye, D.P.; Vitale, M.G. Burden of care in families of patients with early onset scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. B 2019, 29, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, J.A.; Ge, D.H.; Boden, E.; Hanstein, R.; Alvandi, L.M.; Lo, Y.; Hwang, S.; Samdani, A.F.; Sponseller, P.D.; Garg, S.; et al. Posterior-only Resection of Single Hemivertebrae with 2-Level Versus >2-Level Fusion: Can We Improve Outcomes? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2022, 42, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffernan, M.J.; Younis, M.; Glotzbecker, M.P.; Garg, S.; Leonardi, C.; Poon, S.C.; Brooks, J.T.; Sturm, P.F.; Sponseller, P.D.; Vitale, M.G.; et al. The Effect of Surgeon Experience on Outcomes Following Growth Friendly Instrumentation for Early Onset Scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2022, 42, e132–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, I.J.; Saarinen, A.J.; White, K.K.; McClung, A.; Yazici, M.; Garg, S.; Thompson, G.H.; Johnston, C.E.; Pahys, J.M.; Vitale, M.G.; et al. Results of growth-friendly management of early-onset scoliosis in children with and without skeletal dysplasias: A matched comparison. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101B, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helenius, I.J.; Sponseller, P.D.; McClung, A.; Pawelek, J.B.; Yazici, M.; Emans, J.B.; Thompson, G.H.; Johnston, C.E.; Shah, S.A.; Akbarnia, B.A. Surgical and Health-related Quality-of-Life Outcomes of Growing Rod “Graduates” with Severe versus Moderate Early-onset Scoliosis. Spine 2019, 44, 698–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstenburg, J.; Heard, J.B.; Sturm, P.M.; Blakemore, L.; Li, Y.; Ihnow, S.B.; Shah, S.A.; Pediatric Spine Study Group. Does Transitioning to a Brace Improve HRQoL after Casting for Early Onset Scoliosis? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2023, 43, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, H.; Fano, A.N.; Ball, J.; Roye, B.D.; George, A.; Garg, S.; Erickson, M.; Samdani, A.; Skaggs, D.; Roye, D.P.; et al. Uncorrected Pelvic Obliquity Is Associated with Worse Health-related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in Children and Their Caregivers at the End of Surgical Treatment for Early Onset Scoliosis (EOS). J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2022, 42, e390–e396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Auran, E.; Fields, M.W.; Hung, C.W.; Hilaire, T.S.; Roye, B.; Sturm, P.; Garg, S.; Sanders, J.; Oetgen, M.; et al. Serial casting for early onset scoliosis and its effects on health-related quality of life during and after discontinuation of treatment. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.; Marciano, G.; Redding, G.; Ha, J.; Luhmann, S.; Garg, S.; Roye, D.; White, K.; Pediatric Spine Study Group. Association between health-related quality of life outcomes and pulmonary function testing. Spine Deform. 2021, 9, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H.M.; Mueller, J.; Konigsberg, M.; Ball, J.B.; Hilaire, T.S.; Pawelek, J.B.; Roye, D.P.; Cahill, P.; Sturm, P.; Smith, J.; et al. Improvement of Pulmonary Function Measured by Patient-reported Outcomes in Patients with Spinal Muscular Atrophy after Growth-friendly Instrumentation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2021, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nossov, S.B.; Quinonez, A.; SanJuan, J.; Gaughan, J.P.; Pahys, J.; Samdani, A.; Flynn, J.; Mayer, O.H.; Garg, S.; Glotzbecker, M.; et al. Does ventilator use status correlate with quality of life in patients with early-onset scoliosis treated with rib-based growing system implantation? Spine Deform. 2022, 10, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, N.; Olivella, G.; Fitzgerald, R.E.; Smith, J.T.; Sturm, P.F.; Sponseller, P.D.; Karlin, L.I.; Luhmann, S.J.; Torres-Lugo, N.J.; Hilaire, T.S.; et al. Evaluating the Efficacy of Rib-to-pelvis Growth-friendly Surgery for the Treatment of Non-ambulatory Early-Onset Scoliosis Myelomeningocele Patients. JAAOS Glob. Res. Rev. 2022, 6, e22.00090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo, B.A.; McClung, A.; Jo, C.-H.; Sanders, J.O.; Yaszay, B.; Oetgen, M.E. Effect of Etiology, Radiographic Severity, and Comorbidities on Baseline Parent-Reported Health Measures for Children with Early-Onset Scoliosis. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2021, 103, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roye, B.D.; Children’s Spine Study Group; Simhon, M.E.; Matsumoto, H.; Garg, S.; Redding, G.; Samdani, A.; Smith, J.T.; Sponseller, P.; Vitale, M.G.; et al. Bigger is better: Larger thoracic height is associated with increased health related quality of life at skeletal maturity. Spine Deform. 2020, 8, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roye, B.D.; Fano, A.N.; Matsumoto, H.; Fields, M.W.; Emans, J.B.; Sponseller, P.; Smith, J.T.; Thompson, G.H.; White, K.K.; Vitale, M.G. The Impact of Unplanned Return to the Operating Room on Health-related Quality of Life at the End of Growth-friendly Surgical Treatment for Early-onset Scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2022, 42, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, A.J.; Sponseller, P.D.; Andras, L.M.; Skaggs, D.L.; Emans, J.B.; Thompson, G.H.; Helenius, I.J.; the Pediatric Spine Study Group. Matched Comparison of Magnetically Controlled Growing Rods with Traditional Growing Rods in Severe Early-Onset Scoliosis of ≥90°: An Interim Report on Outcomes 2 Years After Treatment. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2022, 104, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, K.A.; Ramo, B.; McClung, A.; Thornberg, D.; Yazsay, B.; Sturm, P.; Jo, C.-H.; Oetgen, M.E. Impact of surgical treatment on parent-reported health related quality of life measures in early-onset scoliosis: Stable but no improvement at 2 years. Spine Deform. 2023, 11, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhofste, B.P.; Emans, J.B.; Miller, P.E.; Birch, C.M.; Thompson, G.H.; Samdani, A.F.; Perez-Grueso, F.J.S.; McClung, A.M.; Glotzbecker, M.P.; on behalf of the Pediatric Spine Study Group. Growth-Friendly Spine Surgery in Arthrogryposis Multiplex Congenita. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2021, 103, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreon, L.Y.; Sanders, J.O.; Diab, M.; Sucato, D.J.; Sturm, P.F.; Glassman, S.D. The Minimum Clinically Important Difference in Scoliosis Research Society-22 Appearance, Activity, and Pain Domains after Surgical Correction of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2010, 35, 2079–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, C.H.; Lenke, L.G.; Sucato, D.J.; Richards, B.S.; Emans, J.B.; Vitale, M.G.; Erickson, M.A.; Sanders, J.O. Selective Thoracic Fusion in Lenke 1C Curves. Spine 2013, 38, 1380–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, N.D.; Jeffrey, H.; Anna, M.; Browne, R.; Sucato, D.J. Residual Thoracic Hypokyphosis after Posterior Spinal Fusion and Instrumentation in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2012, 37, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, Z.; Oswald, T.; Sanders, J.; Diab, M. Prevalence and Predictors of Pain in Surgical Treatment of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2011, 36, 825–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, S.J.; Lenke, L.G.; Erickson, M.; Bridwell, K.H.; Richards, B.S. Correction of Moderate (<70 Degrees) Lenke 1A and 2A Curve Patterns: Comparison of Hybrid and All-pedicle Screw Systems at 2-year Follow-up. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2012, 32, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieberg, C.B.; Simons, L.E.; Edelstein, M.R.; DeAngelis, M.R.; Pielech, M.; Sethna, N.; Hresko, M.T. Pain Prevalence and Trajectories Following Pediatric Spinal Fusion Surgery. J. Pain 2013, 14, 1694–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.W.; Savage, J.W.; Schwartz, D.G.; Carreon, L.Y.; Sucato, D.J.; Sanders, J.O.; Richards, B.S.; Lenke, L.G.; Emans, J.B.; Parent, S.; et al. Male-Female Differences in Scoliosis Research Society-30 Scores in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2011, 36, E53–E59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J.O.; Carreon, L.Y.; Sucato, D.J.; Sturm, P.F.; Diab, M.; Spinal Deformity Study Group. Preoperative and Perioperative Factors Effect on Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Surgical Outcomes. Spine 2010, 35, 1867–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theologis, A.A.; Tabaraee, E.; Lin, T.; Lubicky, J.; Diab, M. Type of Bone Graft or Substitute Does Not Affect Outcome of Spine Fusion with Instrumentation for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2015, 40, 1345–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebracki, K.; Thawrani, D.; Oswald, T.S.; Anadio, J.M.; Sturm, P.F. Predictors of Emotional Functioning in Youth after Surgical Correction of Idiopathic Scoliosis. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2013, 33, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djurasovic, M.; Glassman, S.D.; Sucato, D.J.; Lenke, L.G.; Crawford, C.H.; Carreon, L.Y. Improvement in Scoliosis Research Society-22R Pain Scores after Surgery for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Spine 2018, 43, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemani, V.M.; Kim, H.J.; Bjerke-Kroll, B.T.; Yagi, M.; Sacramento-Dominguez, C.; Akoto, H.; Papadopoulos, E.C.; Sanchez-Perez-Grueso, F.; Pellise, F.; Nguyen, J.T.; et al. Preoperative Halo-Gravity Traction for Severe Spinal Deformities at an SRS-GOP Site in West Africa. Spine 2015, 40, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrini, S.; Negrini, F.; Fusco, C.; Zaina, F. Idiopathic scoliosis patients with curves more than 45 Cobb degrees refusing surgery can be effectively treated through bracing with curve improvements. Spine J. 2011, 11, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyanji, F.; Desai, S. Minimally invasive surgical options for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Semin. Spine Surg. 2015, 27, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa-Moreau, E.; Labelle, H.; Mac-Thiong, J.M. Radiological and Clinical Outcome of Non Surgical Management for Pediatric High Grade Spondylolisthesis. In Research into Spinal Deformities; Aubin, C.E., Stokes, I.A.F., Labelle, H., Moreau, A., Eds.; Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; Ios Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 158, pp. 177–181. [Google Scholar]

- Diebo, B.G.; Segreto, F.A.; Solow, M.; Messina, J.C.; Paltoo, K.; Burekhovich, S.A.; Bloom, L.R.; Cautela, F.S.; Shah, N.V.; Passias, P.G.; et al. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Care in an Underserved Inner-City Population: Screening, Bracing, and Patient- and Parent-Reported Outcomes. Spine Deform. 2019, 7, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godzik, J.; Holekamp, T.F.; Limbrick, D.D.; Lenke, L.G.; Park, T.; Ray, W.Z.; Bridwell, K.H.; Kelly, M.P. Risks and outcomes of spinal deformity surgery in Chiari malformation, Type 1, with syringomyelia versus adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2015, 15, 2002–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mens, R.H.; Bisseling, P.; de Kleuver, M.; van Hooff, M.L. Relevant impact of surgery on quality of life for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A registry-based two-year follow-up cohort study. Bone Jt. J. 2022, 104-B, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Sun, W.; Xu, L.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, Z. Minimally invasive scoliosis surgery assisted by O-arm navigation for Lenke Type 5C adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A comparison with standard open approach spinal instrumentation. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2017, 19, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Burke, M.C.; Gagnier, J.; Caird, M.S.; Farley, F.A. Comparison of EOSQ-24 and SRS-22 Scores in Congenital Scoliosis: A Preliminary Study. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2020, 40, e182–e185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.S.; Boyer, N.; Meyers, A.; Aziz, H.; Aminian, A. Restoration of thoracic kyphosis in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with patient-specific rods: Did the preoperative plan match postoperative sagittal alignment? Eur. Spine J. 2023, 32, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.; Young, D.; de Klerk, N.; Bebbington, A.; Baikie, G.; Leonard, H. Impact of Scoliosis Surgery on Activities of Daily Living in Females with Rett Syndrome. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2009, 29, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schorling, D.C. Coagulation disorders in Duchenne muscular dystrophy? Results of a registry-based online survey. Acta Myol. 2020, 39, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, A.M.; Tomatsu, S.; Gottesman, G.S.; Smith, M.; Orii, T. International Morquio A Registry: Clinical manifestation and natural course of Morquio A disease. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007, 30, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganesh, A.; Rose, J.B.; Wells, L.; Ganley, T.; Gurnaney, H.; Maxwell, L.G.; DiMaggio, T.; Milovcich, K.; Scollon, M.; Feldman, J.M.; et al. Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blockade for Inpatient and Outpatient Postoperative Analgesia in Children. Anesth. Analg. 2007, 105, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.-A.; Brenn, B.; Cho, R.; Samdani, A.; Diu, M.; Fedorak, G.; Gupta, P.; Kuestner, M.; Lawing, C.; Luhmann, S.; et al. Effect of gabapentin on length of stay, opioid use, and pain scores in posterior spinal fusion for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: A retrospective review across a multi-hospital system. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMulkin, M.L.; Gordon, A.B.; Caskey, P.M.; Tompkins, B.J.; Baird, G.O. Outcomes of Orthopaedic Surgery with and without an External Femoral Derotational Osteotomy in Children with Cerebral Palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2016, 36, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.H.; Viehweger, E.; Stout, J.; Novacheck, T.F.; Gage, J.R. Comprehensive Treatment of Ambulatory Children with Cerebral Palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2004, 24, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilat, R.; Haunschild, E.D.; Huddleston, H.; Parvaresh, K.C.; Chahla, J.; Yanke, A.B.; Cole, B.J. Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation of the Knee in Adolescent Patients and the Effect of Physeal Closure. Arthrosc. J. Arthrosc. Relat. Surg. 2021, 37, 1588–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausett, W.; Reid, D.; Larmer, P.; Garrett, N. Patient acceptance of knee symptoms and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction improves with physiotherapy treatment. N. Z. J. Physiother. 2023, 51, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardja, R.; Love, H.; Clatworthy, M.G.; Monk, A.P.; Young, S.W. Higher Rate of Return to Preinjury Activity Levels after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction with a Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone Versus Hamstring Tendon Autograft in High-Activity Patients: Results from the New Zealand ACL Registry. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 3488–3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, A.; Love, H.; Young, S.W.; Frampton, C.M. Comparative Study of ACL Reconstruction with Hamstring Versus Patellar Tendon Graft in Young Women: A Cohort Study from the New Zealand ACL Registry. Am. J. Sports Med. 2023, 51, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.R.; Spindler, K.P.; Amendola, A.; Andrish, J.T.; Kaeding, C.C.; Marx, R.G.; McCarty, E.C.; Parker, R.D.; Harrell, F.E.; An, A.Q.; et al. Which Preoperative Factors, Including Bone Bruise, Are Associated with Knee Pain/Symptoms at Index Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction (ACLR)?: A Multicenter Orthopaedic Outcomes Network (MOON) ACLR Cohort Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 1778–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, M.J.; Logerstedt, D.S.; Grindem, H.; Axe, M.J.; Risberg, M.A.; Engebretsen, L.; Huston, L.J.; Spindler, K.P.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Does Extended Preoperative Rehabilitation Influence Outcomes 2 Years after ACL Reconstruction? A Comparative Effectiveness Study Between the MOON and Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohorts. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 2608–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, R.A.; Granan, L.-P.; Dunn, W.R.; Amendola, A.; Andrish, J.T.; Brophy, R.; Carey, J.L.; Flanigan, D.; Huston, L.J.; Jones, M.; et al. Cross-cultural comparison of patients undergoing ACL reconstruction in the United States and Norway. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010, 18, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mather, R.C.; Koenig, L.; Kocher, M.S.; Dall, T.M.; Gallo, P.; Scott, D.J.; Bach, B.R.; Spindler, K.P.; the MOON Knee Group. Societal and Economic Impact of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2013, 95, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkumar, P.N.; Tariq, M.B.; Amendola, A.; Andrish, J.T.; Brophy, R.H.; Dunn, W.R.; Flanigan, D.C.; Huston, L.J.; Jones, M.H.; Kaeding, C.C.; et al. Risk Factors for Loss to Follow-up in 3202 Patients at 2 Years after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Implications for Identifying Health Disparities in the MOON Prospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 3173–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, R.W.; Dunn, W.R.; Amendola, A.; Andrish, J.T.; Bergfeld, J.; Kaeding, C.C.; Marx, R.G.; McCarty, E.C.; Parker, R.D.; Wolcott, M.; et al. Risk of Tearing the Intact Anterior Cruciate Ligament in the Contralateral Knee and Rupturing the Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft during the First 2 Years after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A prospective MOON cohort study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindanger, L.; Strand, T.; Mølster, A.O.; Solheim, E.; Inderhaug, E. Return to Play and Long-term Participation in Pivoting Sports after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 2019, 47, 3339–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grindem, H.; Granan, L.P.; Risberg, M.A.; Engebretsen, L.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; Eitzen, I. How does a combined preoperative and postoperative rehabilitation programme influence the outcome of ACL reconstruction 2 years after surgery? A comparison between patients in the Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort and the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Chang, B.; Voleti, P.B.; Berkanish, P.; Cohn, M.R.; Altchek, D.W.; Allen, A.A.; Williams, R.J. Preoperative Short Form Health Survey Score Is Predictive of Return to Play and Minimal Clinically Important Difference at a Minimum 2-Year Follow-up after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 2784–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Voleti, P.B.; Berkanish, P.; Chang, B.; Cohn, M.R.; Williams, R.J.; Allen, A.A. Return to Play and Patient Satisfaction after ACL Reconstruction. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2017, 99, 720–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, B.U.; Voleti, P.B.; Chang, B.; Berkanish, P.; Mahony, G.T.; Williams, R.J.; Altchek, D.W.; Allen, A.A. Comparative Influence of Sport Type on Outcome after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction at Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Arthroscopy 2017, 33, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randsborg, P.-H.; Cepeda, N.; Adamec, D.; Rodeo, S.A.; Ranawat, A.; Pearle, A.D. Patient-Reported Outcome, Return to Sport, and Revision Rates 7-9 Years after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Results from a Cohort of 2042 Patients. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauck, R.C.; Apostolakos, J.M.; Nwachukwu, B.U.; Schneider, B.L.; Williams, I.R.J.; Dines, J.S.; Altchek, D.W.; Pearle, A.; Allen, A.; Stein, B.S.; et al. Return to Sport after Bone–Patellar Tendon–Bone Autograft ACL Reconstruction in High School–Aged Athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senorski, E.H.; Samuelsson, K.; Thomeé, C.; Beischer, S.; Karlsson, J.; Thomeé, R. Return to knee-strenuous sport after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A report from a rehabilitation outcome registry of patient characteristics. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2017, 25, 1364–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundemo, D.; Jacobsson, M.S.; Karlsson, J.; Samuelsson, K.; Beischer, S.; Thomeé, R.; Thomeé, C.; Senorski, E.H. Generalized joint hypermobility does not influence 1-year patient satisfaction or functional outcome after ACL reconstruction. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2022, 30, 4173–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inacio, M.C.; Chen, Y.; Maletis, G.B.; Ake, C.F.; Fithian, D.C.; Granan, L.-P. Injury Pathology at the Time of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Associations with Self-assessment of Knee Function. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2014, 24, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spindler, K.P.; McCarty, E.C.; Warren, T.A.; Devin, C.; Connor, J.T. Prospective Comparison of Arthroscopic Medial Meniscal Repair Technique: Inside-out suture versus entirely arthroscopic arrows. Am. J. Sports Med. 2003, 31, 929–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodmass, J.M.; O’Malley, M.P.; Krych, A.J.; Reardon, P.J.; Johnson, N.R.; Stuart, M.J.; Levy, B.A. Revision Multiligament Knee Reconstruction: Clinical Outcomes and Proposed Treatment Algorithm. Arthroscopy 2017, 34, 736–744.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodmass, J.M.; Sanders, T.L.; Johnson, N.R.; Wu, I.T.; Krych, A.J.; Stuart, M.J.; Levy, B.A. Posterolateral Corner Reconstruction Using the Anatomical Two-Tailed Graft Technique: Clinical Outcomes in the Multiligament Injured Knee. J. Knee Surg. 2018, 31, 1031–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerr, R.A.; Garvey, K.D.; Ackermann, J.; Matzkin, E.G. Influence of graft diameter on patient reported outcomes after hamstring autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Orthop. Rev. 2019, 11, 8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, E.T.; Withers, D.; King, E.; Franklyn-Miller, A.; Jackson, M.; Moran, R. Return to Play after Patellar Tendon Autograft for Primary Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction in Rugby Players. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2021, 9, 23259671211000460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.M.; Craft, J.A.; Replogle, W.H.; Hydrick, J.M.; Barrett, G.R. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Graft Failure: A comparison of graft type based on age and Tegner activity level. Am. J. Sports Med. 2011, 39, 2194–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartigan, D.E.; Perets, I.; Walsh, J.P.; Close, M.R.; Domb, B.G. Clinical Outcomes of Hip Arthroscopy in Radiographically Diagnosed Retroverted Acetabula. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 2531–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambough, J.B.; Clohisy, J.C.; Baca, G.R.; Zaltz, I.; Trousdale, R.; Millis, M.; Sucato, D.; Kim, Y.-J.; Sink, E.; Schoenecker, P.L.; et al. Does Previous Pelvic Osteotomy Compromise the Results of Periacetabular Osteotomy Surgery? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2015, 473, 1417–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, S.; Evans, S.; Pynsent, P.; O’Hara, J. Mid-term results for hip resurfacing in patients under 30 years old with childhood hip disorders. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2015, 81, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pun, S.Y.; Hosseinzadeh, S.; Dastjerdi, R.; Millis, M.B. What Are the Early Outcomes of True Reverse Periacetabular Osteotomy for Symptomatic Hip Overcoverage? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021, 479, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, T.S.; Jayasekera, N.; Singh, R.; Patel, A.; Kuiper, J.H.; Richardson, J.B. Hip resurfacing arthroplasty: A new method to assess and quantify learning phase. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2014, 80, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, T.S.; Jayasekera, N.; Singh, R.; Patel, A.; Roulahamin, N.; Kuiper, J.H.; Richardson, J.B. Efficacy of hip resurfacing arthroplasty: 6 year results from an international multisurgeon prospective cohort study. Acta Orthop. Belg. 2015, 81, 197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, T.S.; Kuiper, J.H.; Dixey, J.; Richardson, J.B. Hip resurfacing for rheumatoid arthritis: Independent assessment of 11-year results from an international register. Int. Orthop. 2011, 35, 803–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulakh, T.S.; Rao, C.; Kuiper, J.-H.; Richardson, J.B. Hip resurfacing and osteonecrosis: Results from an independent hip resurfacing register. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2010, 130, 841–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, J.G.; Turnball, G.S.; Ker, A.M.; Breusch, S.J. Return to work and sports after total hip replacement. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2013, 133, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaunay, C.; Hamadouche, M.; Girard, J.; Duhamel, A.; The SoFCOT Group. What Are the Causes for Failures of Primary Hip Arthroplasties in France? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 3863–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devane, P.; Horne, G.; Gehling, D.J. Oxford Hip Scores at 6 Months and 5 Years Are Associated with Total Hip Revision within the Subsequent 2 Years. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 3870–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, G.J.; Hooper, N.M.; Rothwell, A.G.; Hobbs, T. Bilateral Total Joint Arthroplasty: The Early Results from the New Zealand National Joint Registry. J. Arthroplast. 2009, 24, 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeyaseelan, L.; Park, S.S.-H.; Al-Rumaih, H.; Veljkovic, A.; Penner, M.J.; Wing, K.J.; Younger, A. Outcomes Following Total Ankle Arthroplasty: A Review of the Registry Data and Current Literature. Orthop. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 50, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, A.J.; Hooper, G.J.; Rothwell, A.; Frampton, C. Survival and functional outcome after revision of a unicompartmental to a total knee replacement: The New Zealand National Joint Registry. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2010, 92, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothwell, A.G.; Hooper, G.J.; Hobbs, A.; Frampton, C.M. An analysis of the Oxford hip and knee scores and their relationship to early joint revision in the New Zealand Joint Registry. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2010, 92, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, M.D.; Gross, T.P. Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing in patients younger than 50 years: A retrospective analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2017, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, A.; Arden, N.K.; Cooper, C.; Javaid, M.K.; Carr, A.J.; Field, R.E.; Dieppe, P.A. Predictors of outcomes of total knee replacement surgery. Rheumatology 2012, 51, 1804–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanois, R.E.; Gwam, C.U.; Mohamed, N.; Khlopas, A.; Chughtai, M.; Malkani, A.L.; Mont, M.A. Midterm Outcomes of Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty with the Use of a Multihole Highly-Porous Titanium Shell. J. Arthroplast. 2017, 32, 2806–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M.; Johnston, L.R.; Sripada, S.; Mcleod, G.G.; Jariwala, A.C. Cemented total hip replacement in patients under 55 years. Acta Orthop. 2018, 89, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Duff, M.J.; Amstutz, H.C.; Dorey, F.J. Metal-on-Metal Hip Resurfacing for Obese Patients. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2007, 89, 2705–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, S.; Burström, K.; Zethraeus, N.; Eneqvist, T.; Garellick, G.; Rolfson, O. Assessment of the Swedish EQ-5D experience-based value sets in a total hip replacement population. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 2963–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfson, O.; Kärrholm, J.; Dahlberg, L.E.; Garellick, G. Patient-reported outcomes in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register: Results of a nationwide prospective observational study. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2011, 93, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarewich, C.A.; Anderson, M.B.; Gililland, J.M.; Pelt, C.E.; Peters, C.L. Ten-year survivorship of primary total hip arthroplasty in patients 30 years of age or younger. Bone Jt. J. 2018, 100-B, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, G.A.; Kelly, R.M.; McDonnell, S.M.; Walsh, F.; O’byrne, J.M.; Kenny, P.J. Primary total hip arthroplasty: Registry data for fixation methods and bearing options at a minimum of 10 years. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 188, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winther, S.B.; Foss, O.A.; Wik, T.S.; Davis, S.P.; Engdal, M.; Jessen, V.; Husby, O.S. 1–year follow–up of 920 hip and knee arthroplasty patients after implementing fast–track. Acta Orthop. 2015, 86, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, M.; Cardenas, C.; Astarita, E.; Moya, E.; Bellotti, V. Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty: Mid-Term Results in 486 Cases and Current Indication in Our Institution. HIP Int. 2014, 24, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Geller, J.A.; Nyce, J.D.; Choi, J.K.; Macaulay, W. Does Ipsilateral Knee Pain Improve after Hip Arthroplasty? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2012, 470, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, M.; Gwam, C.U.; Khlopas, A.; Sodhi, N.; Delanois, R.E.; Spindler, K.P.; Mont, M.A. No Correlation Between Press Ganey Survey Responses and Outcomes in Post–Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanois, R.E.; Gwam, C.U.; Mistry, J.B.; Chughtai, M.; Khlopas, A.; Yakubek, G.; Ramkumar, P.N.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Mont, M.A. Does gender influence how patients rate their patient experience after total hip arthroplasty? HIP Int. 2018, 28, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Kim, E.; Khlopas, A.; Chughtai, M.; Gwam, C.; Elmallah, R.K.; Ramkumar, P.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Delanois, R.E.; Muschler, G.; et al. What Influences How Patients Rate Their Hospital Stay after Total Hip Arthroplasty? Surg. Technol. Int. 2017, 30, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gwam, C.; Mistry, J.B.; Piuzzi, N.S.; Chughtai, M.; Khlopas, A.; Thomas, M.; Elmallah, R.K.; Muschler, G.; Mont, M.A.; Harwin, S.F.; et al. What Influences How Patients with Depression Rate Hospital Stay after Total Joint Arthroplasty? Surg. Technol. Int. 2017, 30, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.R.; Harris, K.; Dawson, J.; Beard, D.J.; Fitzpatrick, R.; Price, A.J. Floor and ceiling effects in the OHS: An analysis of the NHS PROMs data set. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageberg, E.; Forssblad, M.; Herbertsson, P.; Roos, E.M. Sex Differences in Patient-Reported Outcomes after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: Data from the Swedish knee ligament register. Am. J. Sports Med. 2010, 38, 1334–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenius, B.; Forssblad, M.; Engström, B.; Eriksson, K. Functional recovery after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, a study of health-related quality of life based on the Swedish National Knee Ligament Register. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergerson, E.; Persson, K.; Svantesson, E.; Horvath, A.; Wållgren, J.O.; Karlsson, J.; Musahl, V.; Samuelsson, K.; Senorski, E.H. Superior Outcome of Early ACL Reconstruction versus Initial Non-reconstructive Treatment with Late Crossover to Surgery: A Study from the Swedish National Knee Ligament Registry. Am. J. Sports Med. 2022, 50, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Björnsson, H.; Samuelsson, K.; Karlsson, J.; Forssblad, M. Outcomes after ACL reconstruction with focus on older patients: Results from The Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2014, 22, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granan, L.-P.; Forssblad, M.; Lind, M.; Engebretsen, L. The Scandinavian ACL registries 2004–2007: Baseline epidemiology. Acta Orthop. 2009, 80, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]