The Journey to Sustainable Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescents Living with Cerebral Palsy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Aims

1.2. Research Question

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Child and Parent Characteristics

2.3. Researcher Characteristics

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Management

2.6. Analysis

2.7. Strategies for Enhancing Rigour and Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Themes and Synthesis of Findings

3.3. Themes

3.3.1. Just Doing It

I think, like with most people, you get sick of something so you need a break from it. So that’s probably quite important, variation.(P)

I don’t think it’s a reflection of the programme. Like his physical activity has dropped. However, that’s just been a combination of his age and COVID and starting high school and just a timing thing.(P)

It distracted me. With my anxiety. They’ve [the gym instructors] helped me straighten my mind for about, you know, half an hour or 45 min of the programme.(A)

Just going to play with a friend. Gets him out. Just to see if there’s an activity at the end of it that he looks forward to. However, mostly just ice creams and things…… You know he doesn’t get a high from being physically exhausted. He gets a high from the, the rest afterwards and whatever it is he does afterwards.(P)

3.3.2. Getting the Mix Right

My mum mostly encouraged me to do the biking. My brother and my dad have done frisbee a few times, so I decided to join them because dad wanted me to.(A)

I think it was the family, us going biking, is what got him started. Got his confidence up. Just got him over the hurdle.(P)

Transportation to places, making time available, money for ice chocolates, keeping them on task, reminding him. Just helping him be organised to be ready to go, having a water bottle, nutrition…(P)

I find it difficult to do anything on my own. Having people by my side to not only support but to have fun with. If I make mistakes, and there’s no one to pick me up and support me, it’s a bit more difficult, because I get disheartened.(A)

It’s about the people who do it with him… they make it about the social. It’s not about the slog up the hill, it’s about everyone getting up there.(P)

I’ll organise what time suits everyone. I’d have to ask everyone what days’ work and if the little kids [siblings] have got something [that has to be done]… probably need to get in the habit of going for runs on certain days or certain times.(A)

I prefer if it’s just me by myself. I just feel like I need some time away from my brother or some people that have been frustrating me, sometimes at school and stuff.(A)

We tend to revolve around a lot of what his sister has to do, because she needs a lot of transport into town, so that affects a lot, [A] would miss out quite a bit.(P)

… because everything’s so much harder and more of an effort for him that actually you almost overcompensate a little bit, and you sort of run rings around him just to ensure he’s getting those things.(P)

I see this in PE. People don’t actually think with their brains. How is this going to work for somebody that has one side of their body not working or has major weakness in the side of the body?… I said to my teacher ‘If I’m not able to do it, are you able to come up with something I’m actually able to do to the best of my ability, not only as a student in your class, but as somebody that actually values sport within life’. He [the teacher] was very slow in the start, but I helped him figure it out in a way that he understood what I had struggles with… because he knows I like to be involved. It was the teacher opening up to seeing how adaption can actually be good for me.(A)

He didn’t enjoy [club name] athletics attitude towards paras. I think he got broken by turning up every week and being last.(P)

If things don’t work out at high school or sports, I’ll have to create something… The reason that he’s chosen to be inactive is because, you know, barriers have come up, not out of choice… I think he would prefer to do an activity than not at all.(P)

3.3.3. Balancing the Continua

3.3.4. Navigating the Systems

She keeps pushing and relentlessly pushing me… It was bit more horrendous last time that happened. I couldn’t do it.(A)

She wouldn’t adapt it. It took you four days to get over it.(P)

If you think there’d been some sort of active, ongoing programme or telling us exactly what to do then, or how to do it, life might have been a bit easier really… A lot of families said if there was something dedicated to these kids around their movement and the running, years and years before, other than kind of what we got, instead “this is as good as it’s gonna (sic) get”.(P)

3.3.5. Planning for Sustained Participation in Physical Activity

Have a deadline, where I had to do it and have a consequence, or a reward if I did it before a certain time. If I did meet the deadline something good, or if I didn’t something bad would happen.(A)

| Plans | Sample of Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|

Adolescent strategies

| Having people to do it with, having activities I like, having a reason to do that and having a reason to keep doing it…At least something five times a week. At least. Cuz (because) two days off is almost too much. (A) Just keeping an eye out for activities at school, extracurricular activities, getting involved with things my friends like so joining maybe a club my friends are in. (A) |

Parents Strategies

| Structured programme helps because you have a time and you have to go. (P) Encouragement and doing more of it. If we do more of it, they know that it’s fun’. (P) Just to get up and do it. Don’t say you’re gonna (going to) do it as a parent and not do it. Just get up and do it. (P) Ice creams, fizz, chocolate and things. (P) |

Set goals and follow dreams

| Being able to bike opens up my life for future 10, 20, 30 years. If I cannot afford a car and I’m living close to the supermarket, I bike and that would be very beneficial. I may be able to go to the movies with friends cuz (because) that’s not too far and its easy roads. (A) I reckon I’ll be around 18, 19, 20 [years old] when I get my black belt (in karate), so that’ll keep me busy for a few more years. I’d definitely like to keep swimming after para swimming. I’ll probably go down to the pool every so often. I’d definitely like to join the squash club, that would be really, really good. I’d start biking places. So, if I go to university, I’d bike to university and back every day, that’d keep me active. (A) To eventually represent New Zealand in an international competition which can either be the Paralympics, the World Champs or the Commonwealth Games. I want it to be in the throwing disciplines. However, with a lot of the people from around New Zealand being quite good, I need to push myself to get better than them. (A) I did have some fanciful dream about going to the gym, getting stronger, because that would be quite good. It’s mainly just a fanciful idea because maybe if I get active, I won’t need it. (A) |

Value supporters

| Mum helps a lot. (A) I think it was the family, us going biking, is what got him started. Got his confidence up. Just got him over the hurdle’. (P) I feel like I do give him that support. It gets tiring, constantly nagging and getting nothing for it. I think, if together, we come up with a plan of where it fits in his week, and I help find him a spot then I think he should be able to do that by himself. (P) |

Build and expand support networks

| I think if he’s around people that are active, he’ll join in. Because he’s quite social. That will have an impact on him. (P) Trying to include other people that he likes, finding coaches or support people that are knowledgeable and fun and … know a bit about physical and learning abilities’. (P) With adult support or peer support as he gets older, having things in place where people are, where those things are organised in advance, that he belongs to a group, if we can and that he has friends or peers that will be involved with him. And using funding as well for that sometimes. (P) If he wanted to choose an activity, then we’d be very keen for him to do that. And if we really disliked it or something, then we would try and get somebody else to support him to do it with or we’d just start doing it if it wasn’t our preference. Yeah, until he was able to do it himself. (P) |

He’s not interested in what I suggest, so my pulling-power on those things or my ability to make it fun is not as much as other people.(P)

I don’t know the answer to getting him to do more outdoor exercise type activities. I don’t have any strategies or plans or thoughts on how to do that yet. I’d have to try and think of ways to inspire him to be more active.(P)

That he’s aware of his abilities and has the motivation to do what he needs to do. For nothing to be a problem for him. It has to come from him eventually.(P)

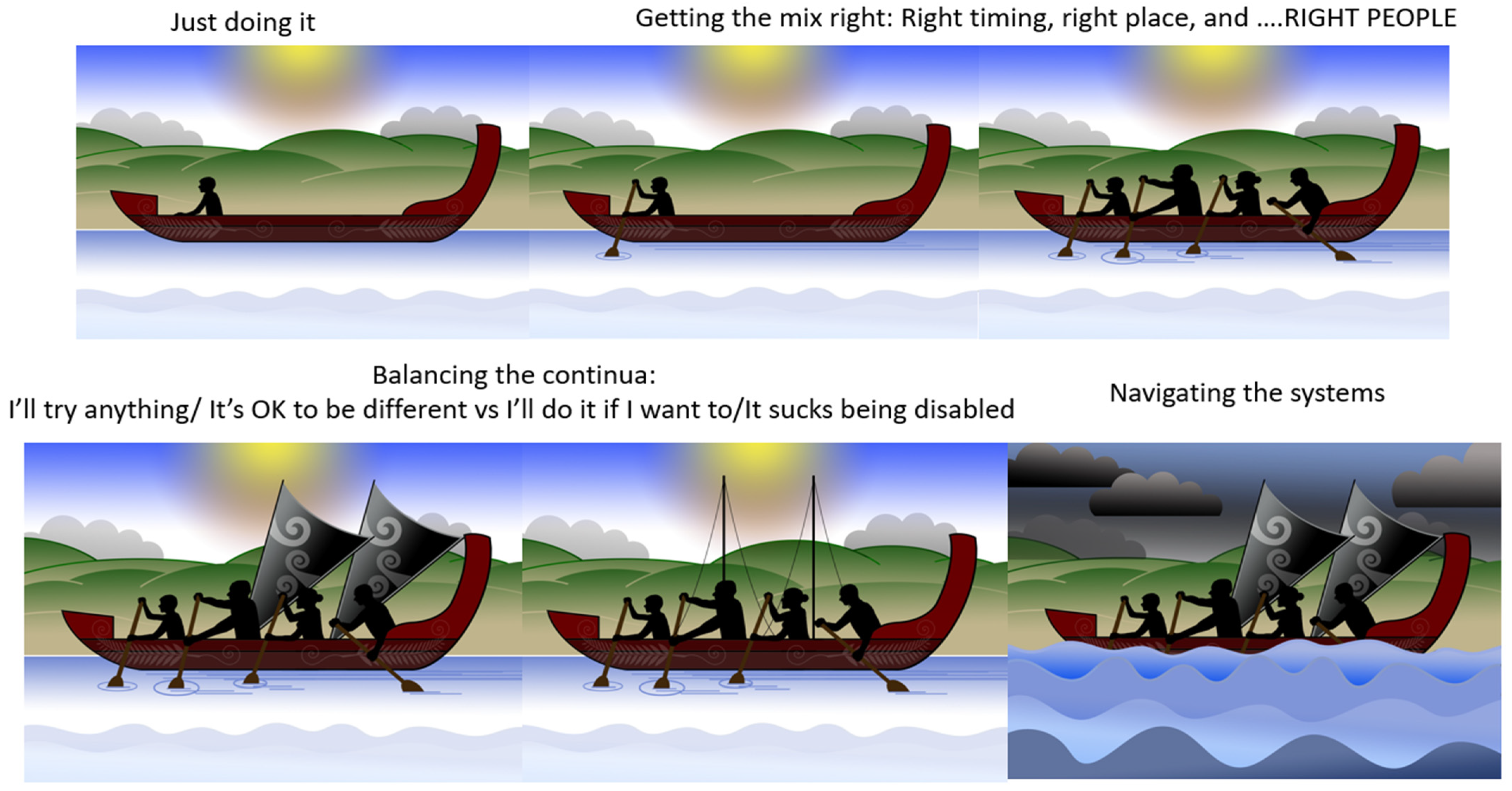

3.3.6. Interpretive Description: Translating the Journey

My son has had a few challenging situations where he refused to do something, and he said to me that he was folding up his sail.(P)

One thing I felt could be included is that while a child is the master of their own waka, it is fundamental that they need to be able to trust their crew to sometimes point the waka in a different direction and show a possibly more interesting path.(P)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategies to Enhance Trustworthiness

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Transferability

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.B.; Shirazipour, C.H.; Allan, V.; Zanhour, M.; Sweet, S.N.; Ginis, K.A.M.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. Integrating insights from the parasport community to understand optimal Experiences: The Quality Parasport Participation Framework. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 37, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Evans, M.B.; Mortenson, W.B.; Noreau, L. Broadening the conceptualization of participation of persons with physical disabilities: A configurative review and recommendations. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1.6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaput, J.-P.; Willumsen, J.; Bull, F.; Chou, R.; Ekelund, U.; Firth, J.; Jago, R.; Ortega, F.; Katzmarzyk, P. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: Summary of the evidence. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Lee, E.; Wagatsuma, M.; Frey, G.; Stanish, H.; Jung, T.; Rimmer, J.H. Research Trends and Recommendations for Physical Activity Interventions Among Children and Youth with Disabilities: A Review of Reviews. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2020, 37, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sit, C.; Aubert, S.; Carty, C.; Silva, D.A.S.; López-Gil, J.F.; Asunta, P.; Palad, Y.; Guisihan, R.; Lee, J.; Nicitopoulos, K.P.A. Promoting physical activity among children and adolescents with disabilities: The translation of policy to practice internationally. J. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 19, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, B.; Kim, Y.; Wilroy, J.; Bickel, C.S.; Rimmer, J.H.; Motl, R.W. Sustainability of exercise intervention outcomes among people with disabilities: A secondary review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1584–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, H.W.; Craig, C.L.; Lambert, E.V.; Inoue, S.; Alkandari, J.R.; Leetongin, G.; Kahlmeier, S. The pandemic of physical inactivity: Global action for public health. Lancet 2012, 380, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adair, B.; Ullenhag, A.; Keen, D.; Granlund, M.; Imms, C. The effect of interventions aimed at improving participation outcomes for children with disabilities: A systematic review. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2015, 57, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, L.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.J.H.; Borodulin, K.; Bull, F.C.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Chastin, S.; et al. Advancing the global physical activity agenda: Recommendations for future research by the 2020 WHO physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines development group. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, G.; Adair, B.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. Effects of a 12 week community-based high-level mobility programme on sustained participation in physical activity by adolescents with cerebral palsy: A single subject research design study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; Granlund, M.; Wilson, P.H.; Steenbergen, B.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Gordon, A.M. Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, G.; Adair, B.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. Do physical activity interventions influence subsequent attendance and involvement in physical activities for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 1682–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.M.; Cassidy, E.E.; Noorduyn, S.G.; O’Connell, N.E. Exercise interventions for cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, E.; Spencer, N.L.I.; Phelan, S.K.; Pritchard-Wiart, L. Player and Parent Experiences with Child and Adolescent Power Soccer Sport Participation. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2020, 40, 637–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahlon, S.; Brubacher-Cressman, K.; Caron, E.; Ramonov, K.; Taubman, R.; Berg, K.; Wright, F.V.; Hilderley, A.J. Opening the Door to Physical Activity for Children with Cerebral Palsy: Experiences of Participants in the BeFAST or BeSTRONG Program. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2019, 36, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaratnam, C.; Howells, K.; Stefanac, N.; Reynolds, K.; Rinehart, N. Parent and Clinician Perspectives on the Participation of Children with Cerebral Palsy in Community-Based Football: A Qualitative Exploration in a Regional Setting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.B.; Moser, T.; Ullenhag, A. The coolest I know—A qualitative study exploring the participation experiences of children with disabilities in an adapted physical activities program. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.; Reid, S.; Elliott, C.; Rosenberg, M.; Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Girdler, S. A realist evaluation of a physical activity participation intervention for children and youth with disabilities: What works, for whom, in what circumstances, and how? BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.E.; Reid, S.; Elliott, C.; Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Girdler, S. ‘It’s important that we learn too’: Empowering parents to facilitate participation in physical activity for children and youth with disabilities. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2019, 26, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duff, S.V.; Kimbel, J.D.; Grant-Beuttler, M.; Sukal-Moulton, T.; Moreau, N.G.; Friel, K.M. Lifelong Fitness in Ambulatory Children and Adolescents with Cerebral Palsy II: Influencing the Trajectory. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, S. What can qualitative studies offer in a world where evidence drives decisions? Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2018, 5, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.I.; Spence, J.C.; Holt, N.L. In the shoes of young adolescent girls: Understanding physical activity experiences through interpretive description. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2011, 3, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Dodd, K.J.; Shields, N. Barriers to and facilitators of physical activity for children with cerebral palsy in special education. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1408–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson Burdine, J.; Thorne, S.; Sandhu, G. Interpretive description: A flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.J.; Rosenbaum, P.; Walter, S.; Russell, D.; Wood, E.; Galuppi, B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 1997, 39, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibald, M.M.; Caine, V.; Ali, S.; Hartling, L.; Scott, S.D. What is left unsaid: An interpretive description of the information needs of parents of children with asthma. Res. Nurs. Health 2015, 38, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer, K.M.; Harwood, M.L.; McCann, C.M.; Crengle, S.M.; Worrall, L.E. The use of interpretive description within Kaupapa Māori research. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidecker, M.J.C.; Paneth, N.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Kent, R.D.; Lillie, J.; Eulenberg, J.B.; Chester, K., Jr.; Johnson, B.; Michalsen, L.; Evatt, M. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2011, 53, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgour, G.; Adair, B.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. More than just having fun! Understanding the experience of involvement in physical activity of adolescents living with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, M.; MacDermid, J.; Connelly, D.; McDougall, J. Current Experiences and Future Expectations for Physical Activity Participation: Perspectives of Young People with Physical Disabilities and Their Rehabilitation Clinicians. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2021, 24, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauruschkus, K.; Nordmark, E.; Hallström, I. “It’s fun, but…” Children with cerebral palsy and their experiences of participation in physical activities. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, E.L.; Boyd, R.N.; Horan, S.A.; Kentish, M.J.; Ware, R.S.; Carty, C.P. Functional electrical stimulation cycling, goal-directed training, and adapted cycling for children with cerebral palsy: A randomized controlled trial. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 1406–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, D.M.; Horrocks, L.; Visser, K.; Todd, G. Adapted bikes: What children and young people with cerebral palsy told us about their participation in adapted dynamic cycling. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2013, 8, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyquist, A.; Moser, T.; Jahnsen, R. Fitness, fun and friends through participation in preferred physical activities: Achievable for children with disabilities? Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2016, 63, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sport New Zealand. Active NZ Spotlight on Disability; Sport New Zeaalnd: Wellington, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zull, A.; Tillmann, V.; Frobose, I.; Anneken, V. Physical activity of children and youth with disabilities and the effect on participation in meaningful leisure-time activities. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauruschkus, K.; Hallstrom, I.; Westbom, L.; Tornberg, A.; Nordmark, E. Participation in physical activities for children with cerebral palsy: Feasibility and effectiveness of physical activity on prescription. Arch. Physiother. 2017, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, B.; Clayton, B.; Brittain, I.; Mackintosh, C. ‘I’ll always find a perfectly justified reason for not doing it’: Challenges for disability sport and physical activity in the United Kingdom. Sport Soc. 2019, 24, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedman, S.E.; Boyd, R.N.; Trost, S.G.; Elliott, C.; Sakzewski, L. Efficacy of Participation-Focused Therapy on Performance of Physical Activity Participation Goals and Habitual Physical Activity in Children with Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2019, 100, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Solmon, M. Integrating self-determination theory with the social ecological model to understand students’ physical activity behaviors. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2013, 6, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Solmon, M.A.; Kosma, M.; Carson, R.L.; Gu, X. Need support, need satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, and physical activity participation among middle school students. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2011, 30, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauruschkus, K.; Nordmark, E.; Hallström, I. Parents’ experiences of participation in physical activities for children with cerebral palsy—Protecting and pushing towards independence. Disabil. Rehabil. 2017, 39, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchison, B.-J.; Goodwin, D.L. “My Child May Be Ready, but I Am Not”: Parents’ Experiences of Their Children’s Transition to Inclusive Fitness Settings. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 2019, 36, 282–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, C.; Nyquist, A.; Jahnsen, R.; Elliott, C.; Ullenhag, A. Enabling physical activity participation for children and youth with disabilities following a goal-directed, family-centred intervention. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 77, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, E.; Regalado, I.C.R.; Galvao, E.; Ferreira, H.N.C.; Badia, M.; Baz, B.O. I Want to Play: Children with Cerebral Palsy Talk About Their Experiences on Barriers and Facilitators to Participation in Leisure Activities. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2020, 32, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiariti, V.; Sauve, K.; Klassen, A.F.; O’Donnell, M.; Cieza, A.; Mâsse, L.C. ‘He does not see himself as being different’: The perspectives of children and caregivers on relevant areas of functioning in cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2014, 56, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienko, S. Understanding the factors that impact the participation in physical activity and recreation in young adults with cerebral palsy (CP). Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2016, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bult, M.K.; Verschuren, O.; Lindeman, E.; Jongmans, M.J.; Westers, P.; Claassen, A.; Ketelaar, M. Predicting leisure participation of school-aged children with cerebral palsy: Longitudinal evidence of child, family and environmental factors. Child Care Health Dev. 2013, 39, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imms, C.; King, G.; Majnemer, A.; Avery, L.; Chiarello, L.; Palisano, R.; Orlin, M.; Law, M. Leisure participation–preference congruence of children with cerebral palsy: A Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment International Network descriptive study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majnemer, A.; Shevell, M.; Law, M.; Rosenbaum, P.; Poulin, C. Assessment of participation and enjoyment in leisure and recreational activities in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2006, 48, 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shikako-Thomas, K.; Shevell, M.; Lach, L.; Law, M.; Schmitz, N.; Poulin, C.; Majnemer, A.; QUALA Group. Are you doing what you want to do? Leisure preferences of adolescents with cerebral palsy. Dev. Neurorehabilit. 2015, 18, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Roberts, R.; Bowman, G.; Crettenden, A. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity participation for children with physical disability: Comparing and contrasting the views of children, young people, and their clinicians. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 41, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimmell, L.J.; Gorter, J.W.; Jackson, D.; Wright, M.; Galuppi, B. “It’s the participation that motivates him”: Physical activity experiences of youth with cerebral palsy and their parents. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2013, 33, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodmansee, C.; Hahne, A.; Imms, C.; Shields, N. Comparing participation in physical recreation activities between children with disability and children with typical development: A secondary analysis of matched data. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 49, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvensalo, M.; Lintunen, T. Life-course perspective for physical activity and sports participation. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2011, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telama, R.; Yang, X.; Leskinen, E.; KANKAANPÄÄ, A.; Hirvensalo, M.; Tammelin, T.; Viikari, J.S.; Raitakari, O.T. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2014, 46, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keawutan, P.; Bell, K.L.; Oftedal, S.; Ware, R.S.; Stevenson, R.D.; Davies, P.S.; Boyd, R.N. Longitudinal physical activity and sedentary behaviour in preschool-aged children with cerebral palsy across all functional levels. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, L.E.; Ziviani, J.; Boyd, R.N. Habitual physical activity of independently ambulant children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: Are they doing enough? Phys. Ther. 2015, 95, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reedman, S.E.; Johnson, E.; Sakzewski, L.; Gomersall, S.; Trost, S.G.; Boyd, R.N. Sedentary behavior in children with cerebral palsy between 1.5 and 12 years: A longitudinal study. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. 2020, 32, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwier, J.N.; Van Schie, P.E.; Becher, J.G.; Smits, D.-W.; Gorter, J.W.; Dallmeijer, A.J. Physical activity in young children with cerebral palsy. Disabil. Rehabil. 2010, 32, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.-T.; Hwang, A.-W.; Liao, H.-F.; Granlund, M.; Kang, L.-J. Understanding the Participation in Home, School, and Community Activities Reported by Children with Disabilities and Their Parents: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Granlund, M. Conceptions of participation in students with disabilities and persons in their close environment. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2004, 16, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Marino, E.; Tremblay, S.; Khetani, M.; Anaby, D. The effect of child, family and environmental factors on the participation of young children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2018, 11, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, N.; Epstein, A.; Jacoby, P.; Kim, R.; Leonard, H.; Reddihough, D.; Whitehouse, A.; Murphy, N.; Downs, J. Modifiable child and caregiver factors that influence community participation among children with Down syndrome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siebert, E.A.; Hamm, J.; Yun, J. Parental Influence on Physical Activity of Children with Disabilities. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 2017, 64, 378–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussen, A.; Howie, L.; Imms, C. Looking to the future: Adolescents with cerebral palsy talk about their aspirations—A narrative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2012, 34, 2103–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin Ginis, K.A.; Ma, J.K.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Rimmer, J.H. A systematic review of review articles addressing factors related to physical activity participation among children and adults with physical disabilities. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reedman, S.E.; Boyd, R.N.; Ziviani, J.; Elliott, C.; Ware, R.S.; Sakzewski, L. Participation predictors for leisure-time physical activity intervention in children with cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2021, 63, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubert, S.; Brazo-Sayavera, J.; González, S.A.; Janssen, I.; Manyanga, T.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Picard, P.; Sherar, L.B.; Turner, E.; Tremblay, M.S. Global prevalence of physical activity for children and adolescents; inconsistencies, research gaps, and recommendations: A narrative review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reedman, S.E.; Boyd, R.N.; Sakzewski, L. The efficacy of interventions to increase physical activity participation of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2017, 59, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.; Khetani, M.; Piskur, B.; van der Holst, M.; Bedell, G.; Schakel, F.; de Kloet, A.; Simeonsson, R.; Imms, C. Towards a paradigm shift in pediatric rehabilitation: Accelerating the uptake of evidence on participation into routine clinical practice. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 1746–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anaby, D.R.; Hand, C.; Bradley, L.; DiRezze, B.; Forhan, M.; DiGiacomo, A.; Law, M. The effect of the environment on participation of children and youth with disabilities: A scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2013, 35, 1589–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaby, D.R.; Law, M.; Feldman, D.; Majnemer, A.; Avery, L. The effectiveness of the Pathways and Resources for Engagement and Participation (PREP) intervention: Improving participation of adolescents with physical disabilities. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2018, 60, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palisano, R.J.; Di Rezze, B.; Stewart, D.; Freeman, M.; Rosenbaum, P.L.; Hlyva, O.; Wolfe, L.; Gorter, J.W. Promoting capacities for future adult roles and healthy living using a lifecourse health development approach. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020, 42, 2002–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Rosenbaum, P.; Gorter, J.W. The ‘F-words’ in childhood disability: I swear this is how we should think! Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.; Imms, C.; Kerr, C.; Adair, B. Sustained participation in community-based physical activity by adolescents with cerebral palsy: A qualitative study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 41, 3043–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, J.; Williams, T.L.; McEachern, B.M.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Tomasone, J.R. Fostering quality experiences: Qualitative perspectives from program members and providers in a community-based exercise program for adults with physical disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 2019, 12, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasone, J.R.; Man, K.E.; Sartor, J.D.; Andrusko, K.E.; Ginis, K.A.M.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E. ‘On-the ground’strategy matrix for fostering quality participation experiences among persons with disabilities in community-based exercise programs. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2023, 69, 102469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B.; Rigby, B.; Netherway, J.; Wang, W.; Dodd-Reynolds, C.; Oliver, E.; Bone, L.; Foster, C. Physical Activity for General Health Benefits in Disabled Children and Disabled Young People: Rapid Evidence Review; UK Department of Health and Social Care: London, UK, 2022.

| Themes and Subthemes | |

|---|---|

| Just doing it | |

| |

| Getting the mix right | |

| |

| |

| |

| Balancing the continua | |

| I’ll try anything | I’ll do it if I want to |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It’s OK to be different | It sucks being disabled |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Navigating the systems | |

| |

| Themes and Subthemes: ‘On Track to Sustained Participation’ | |

|---|---|

| Just doing it | |

| Attendance/Involvement I think two sessions a week. I think that you were really on task, you know they went there, they had a bit of a laugh and a joke, but actually you had a set lesson plan and you just kept it moving. And I think it was a hard hour. (P) I think that’s something he wanted to do … he seems to really enjoy it. (P) | |

| Getting the mix right | |

| Right place I’d like for him to have sports that he can go to for enjoyment. Whether it’s mainstream or adapted, but that he’s got options. Even though he’s got the disability. However, I’m not sure that will be our choice to be honest… (P) | |

| Right time I think it’s really benefited… it’s caught him at the right time because he’s in the right place for this now. (P) I think he does enough. His academics are really important to him. He actually doesn’t have a whole lot of time. The time he does have I think he needs to be a kid and hang out with his friends. We don’t want every last minute filled up. (P) | |

| Right people It’s just nicer with mum or dad cuz (because) then I don’t need to worry about being left behind or having to catch up. With friends, I’d try to keep up or probably ask them if we can take a rest. (A) I think it’s very important when he’s with like-minded people with similar physical abilities. It’s all motivational, he’s definitely in his happy place. (P) If I couldn’t find anyone else I could relate to, it would make it more difficult and arduous’. (A) | |

| Balancing the continua | |

| I’ll try anything | I’ll do it if I want to |

| I am motivated I talked to him about intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and I think he’s got that internal motivation for throwing because it holds his interest. If he can keep up that motivation, that focus and that dedication, I think that will serve him well. (P) | I do not want to I just can’t seem to get him to do his home exercises. So, I think it’s good to be doing some programme that kind of forces him to do it. You can see that he’s doing it properly and give them advice and he will take it from you because what do I know? (P) |

| I like it and it’s my choice Basketball’s just a fun sport to play, that I enjoy and actually I’m kind of good at. Like soccer, I’m terrible. I can’t kick very hard compared to my brother. (A) | Do I have a choice? Swimming is not his choice. Because I don’t want him to drown. It’s a life skill rather than a choice. (P) |

| It makes me feel good It makes me feel better. Healthier in my body. I feel good that I’m doing it. (A) | It’s not for me He’s not a physical person. He’s an indoor Lego, intellectual person. Some people get a buzz out of exerting themselves and others don’t. He’s the type that doesn’t. (P) |

| I will try it if… I think because I need people to do it with me so I can base myself off them and compete with them. Using my competitive side to motivate me. (A) | I need help We admit he is a teenage boy and without a little swift kick in the bum, he would quite happily sit on his bum all day. There’s a lot of motivation from either myself, his mum or even his grandmother…We appreciate he’s a teenage boy, and he needs a little bit of direction. (P) |

| I will try it but… I’m quite a bit tired sometimes doing stuff. I just want to do it. However, my body says I actually can’t because I’m so tired…I get very, very sore muscles. … I would take all my sores and just throw it away and just try to keep going… However, sometimes it overwhelms me and just goes on. And I just can’t do anything. (A) | I do not know if I can I don’t think I’m really that good enough to be in a basketball team. And they look really good compared to me. I’ve never really thought of actually playing sports. (A) |

| It’s OK to be different | It sucks being disabled |

| I am as good as me There are people at school, which are just like, “oh, you can’t do sport, you’re disabled”. However, it’s about teaching them, that, while you might not view me as very good at sport, if you look at my results in a para perspective, I’m actually doing very well. (A) | Moving towards ‘normal’ I think it’s important that we do things to keep him active so that when his friends want to do things, he can keep up with them. Because that has been a problem in the past. You know, his friends are not disabled. He has got a bit upset about it, that he can’t do what they do. (P) |

| I am a para-athlete You have to be patient and you can’t get everything right the first time…I have to work harder…I want to win…I’d like to get good enough to get internationally classified or compete internationally. (A) | I have fewer options In cricket we said I might not be able to play hard ball. I might have to have a special thing where I get to run early but I just want to be like everyone else and running at the normal time. I wouldn’t enjoy it at all. (A) |

| I am supported Just encouraging her. Know that it’s OK. Everyone is different, not everyone’s the same. I always tell my kids, who cares what they think? (P) | I may not be able to when I am older Hopefully I’d still be running but probably not … It’s quite important to keep up running because otherwise my muscles aren’t going to be functioning as well in the future. It would be harder to walk”. (A) |

| I am different The girls will often bike and sometimes he’ll get on his three-wheeler bike. (P) | I am judged There’s activity she would love to do but she just doesn’t do it. Because of her confidence and worrying about what other people will think. It’s a complex thing. You know, being her age, 14, and having other kids looking in on her. (P) |

| I face obstacles Trying to find her something to do is really difficult. I don’t know the pain that she’s feeling every day when she gets home after school, … so I can’t really force her to go and do something. (P) | |

| Navigating the systems | |

| Interpersonal For us as a family it’s been really good that my son had something that he has been participating in for himself and been achieving within that. I mean we all love him succeeding and even his brother does. We’ll be able to do more. We’re always looking for activities that all of us can enjoy at the same time. (P) Organisational We were all talking about why we haven’t known any of this sort of stuff from the HLMP earlier. (P) When we have relievers in [substitute teachers], that’s the big thing, they don’t understand my disability fully. (A) Community Everything’s a minefield, you’ve got to do this, this, this and this. You almost need a guide to guide your way through these things because it’s not easy if you’re just dipping your foot in for the first time. (P) Policy With COVID lockdown, athletics training ended. Missed athletics sports, chance to compete at big events. Missed training leading up to Halberg games. Missed my birthday party which was go-carting. Can’t go swimming. Missed biking, chain is broken and can’t buy new part. Can’t walk in the hills with my walking group. Not walking to and from school bus as no school. (A) He coped with COVID lockdown well. He didn’t like that he couldn’t get out and about to do the activities or see people that he wanted to see. However, he was able to do more physical activity because he wasn’t at school and didn’t have rigid hours or yeah and wasn’t as tired. And COVID gave him the freedom to because there was less traffic around, that we were happier for him to go walking by himself around the local area (which he had never done or wanted to do before). And, yeah, that was really positive for him and made him feel more confident and able… (P) | |

| Themes | ICF | F-Words | fPRC | Social Ecological Model | Framework for Sustained Participation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

‘Just doing it’ | Participation | Friendship Fun | Participation: Attendance Involvement | Intrapersonal | Getting started |

‘Getting the mix right’ | Contextual factors | Family factors | Contextual factors | Intrapersonal Interpersonal | Sense of belonging The coach is important Being passionate |

‘Balancing the continua’ | Body function and structure Activity Participation Personal factors | Fitness Function Friendship Fun | Preferences Activity competence Sense of self Transactional relations between constructs | Intrapersonal | Wanting to succeed Being passionate Sense of belonging |

‘Navigating the systems’  | Environmental and contextual factors | Family factors Future | Contextual and environmental factors | Interpersonal Organisational Community Public policy | The coach is important Endorsement of continue Endorsement to support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kilgour, G.; Stott, N.S.; Steele, M.; Adair, B.; Hogan, A.; Imms, C. The Journey to Sustainable Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescents Living with Cerebral Palsy. Children 2023, 10, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091533

Kilgour G, Stott NS, Steele M, Adair B, Hogan A, Imms C. The Journey to Sustainable Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescents Living with Cerebral Palsy. Children. 2023; 10(9):1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091533

Chicago/Turabian StyleKilgour, Gaela, Ngaire Susan Stott, Michael Steele, Brooke Adair, Amy Hogan, and Christine Imms. 2023. "The Journey to Sustainable Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescents Living with Cerebral Palsy" Children 10, no. 9: 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091533

APA StyleKilgour, G., Stott, N. S., Steele, M., Adair, B., Hogan, A., & Imms, C. (2023). The Journey to Sustainable Participation in Physical Activity for Adolescents Living with Cerebral Palsy. Children, 10(9), 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091533