A Conceptual Model Depicting How Children Are Affected by Parental Cancer: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Participants

2.4. Interviews

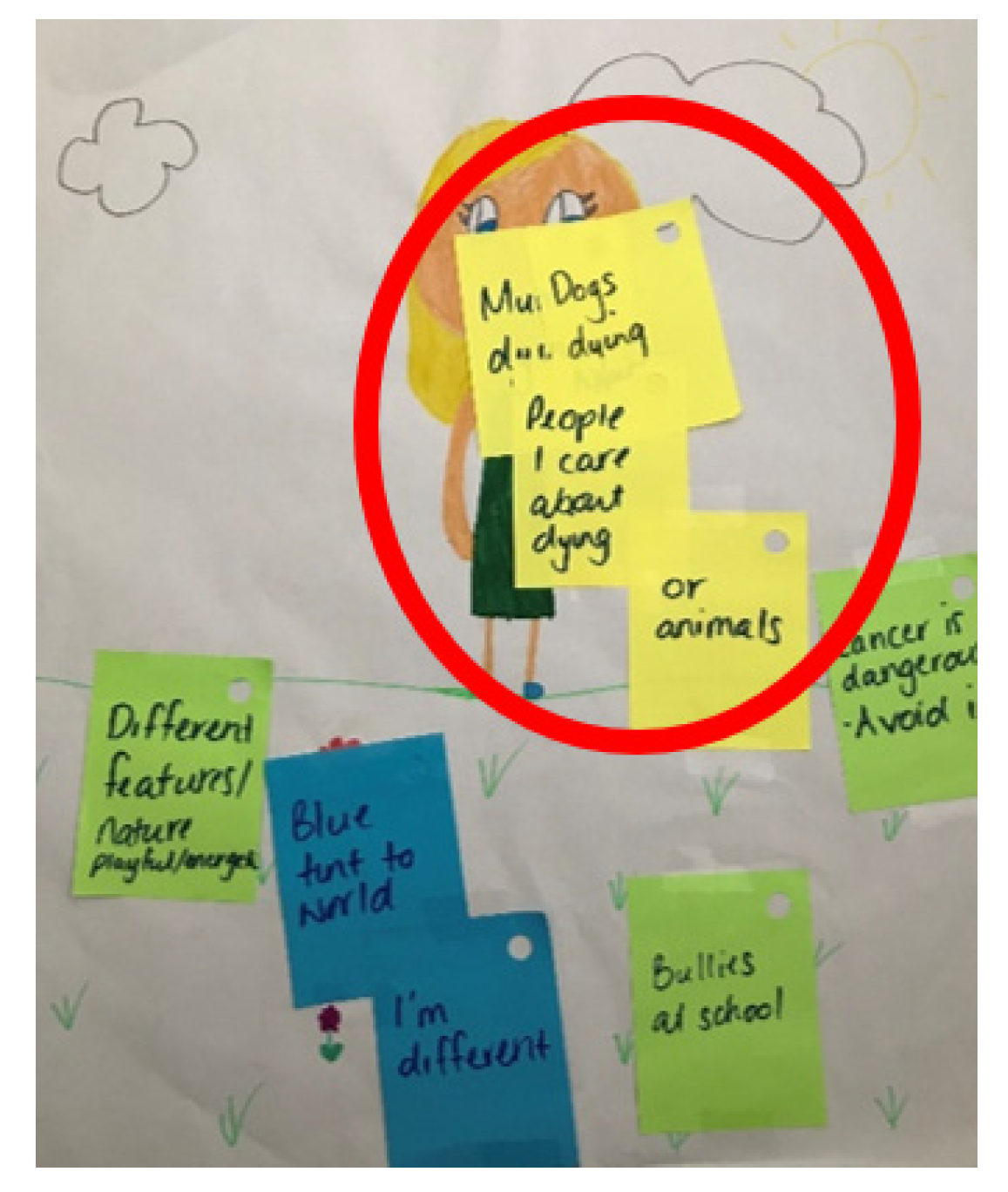

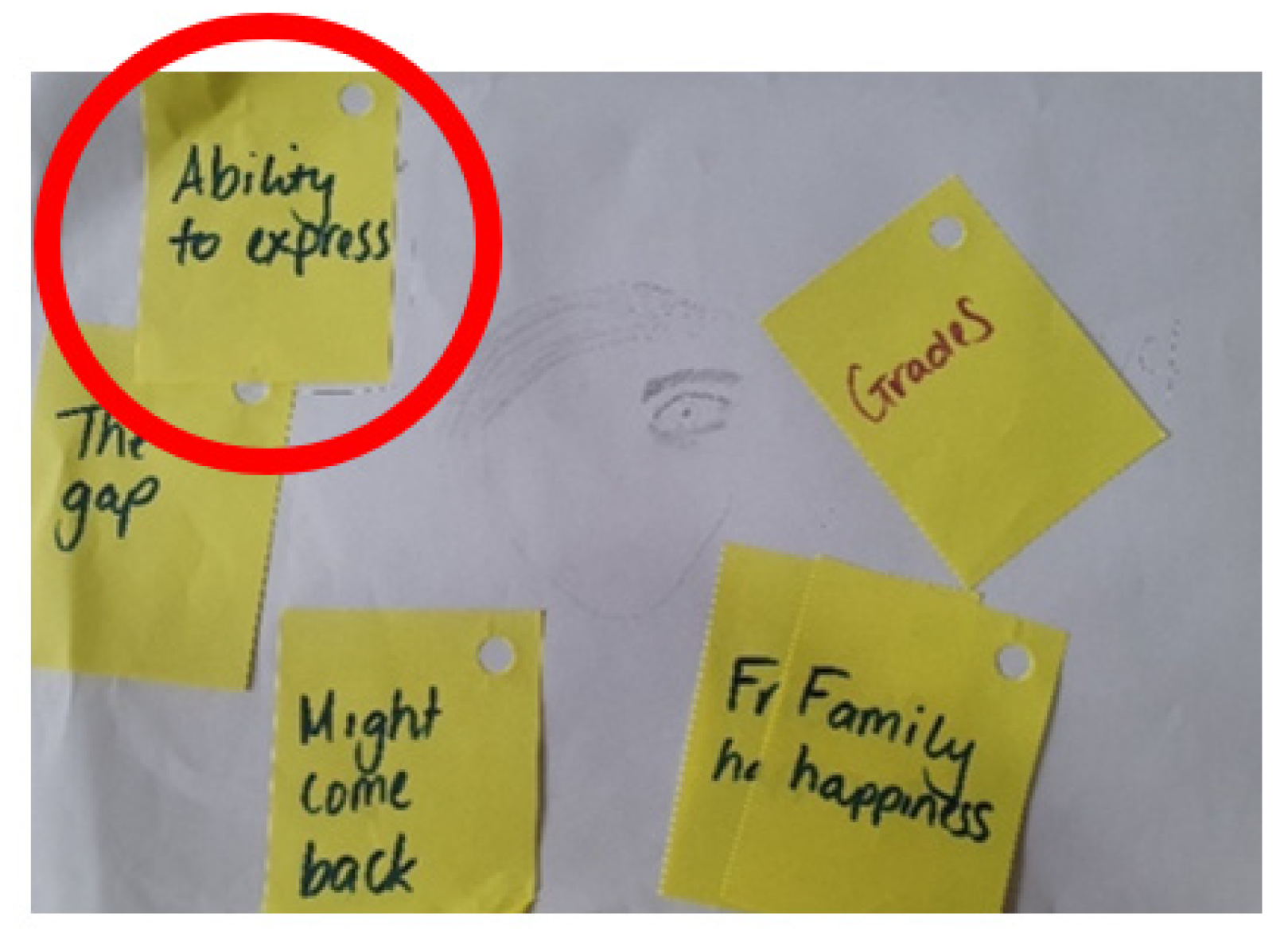

2.5. Children’s Activity

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Findings

3.1. Children

Worried, Distressed, and Alone

Interviewer: “You feel worried and frustrated a lot of time?”

Child: “Yes”.

Interviewer: “When do you feel happy?”

Child: “When Mummy’s okay and she’s doing stuff” (Batari; female: 8.5 years).

Child: “I spent more time with her before she got sick. She’s having another operation to take the bag away and then we’re going to have more time to be with her again”.

Interviewer: “Are you looking forward to that?”

Child: “I’ve been waiting for it for 1000 years” (Arianna, female: 6.5 years).

Interviewer: “Can you tell me what you know about mum’s cancer?”

Child: “Brain cancer, kills people” (notably, the parent did not have a brain cancer diagnosis).

Interviewer: “Did someone you know have brain cancer?”

Child: “It’s Granddad. He died” (Arianna; female: 6.5 years).

Interviewer: “Do you know what you would ask?”

Child: “I’m generally unsure of it, I just feel the need to know something”.

Interviewer: “Is it something you can ask Mum about?”

Child: “It might be, but I’m unsure of how to do this” (Lucas, male: 12 years).

3.2. Parents

Children’s Needs Are Unattended

“If you have to phone to change an appointment, you don’t go to a receptionist. You go to some third party who may or may not be able to change an appointment or answer a question, so it’s absolutely hopeless whatever that system is, so we don’t even bother” (Parent 1)

“There’s always something that comes up. We’ve tried to plan for the best but expect the worst”.

“While he’s neutropenic you can eat an apple, but you’ve got to wash your hands; wash your face before you kiss or hug dad; you’ve just got to be really conscious. Lots of extra handwashing. We have good hygiene, but I’m just seeing bugs everywhere. It’s cleaning constantly” (Parent 2).

“The children pick up on my stress. They certainly pick up on his stress. My five-year-old was wetting the bed and the more [patient] got sleep deprived because he was getting up in the middle of the night changing sheets, the less tolerant of it he became and that becomes like a negative cycle” (Parent 9),

the family had limited childcare support,

“The first time I brought her to the hospital, she saw a lot of patients in very bad conditions” (Parent 8),

or there was an emergency.

“He [patient] got very sick and ended up in the high intensity unit because they had to call a code blue, which was probably a bit of a shock seeing Dad so sick in hospital, and for [child]—that was probably the hardest week for him. It was stressful for all of us; me trying to still work, going into hospital every night” (Parent 4).

3.3. HPs

Children Are Invisible

“That’s [screening] something we initiate ourselves. We normally try to get as much information about their social life and their family life as we can and then if they tell us they do have kids, then we explore” (HP5).

“Sometimes they [children] will process it through play therapy, but not be able to articulate it verbally how they’re feeling. Then, once the diagnosis has got to a safer distance, they might be able to engage in some verbal dialogue, or as they’re getting a little bit older, they might be in a position to articulate and want to revisit what’s happened” (HP9).

“I’m not experienced in child psychology. I really am fearful that I would be doing an injustice opening up a conversation that I didn’t have the tools to complete” (HP3).

“I feel a lot of the time they shield the kids, so they don’t bring them in” (HP4).

“With the ones that are reluctant to talk, it is a lot more challenging, and I feel that even when I am trying to build more of a rapport with them and sneakily get some questions in here and there, it’s not always going to go well” (HP12).

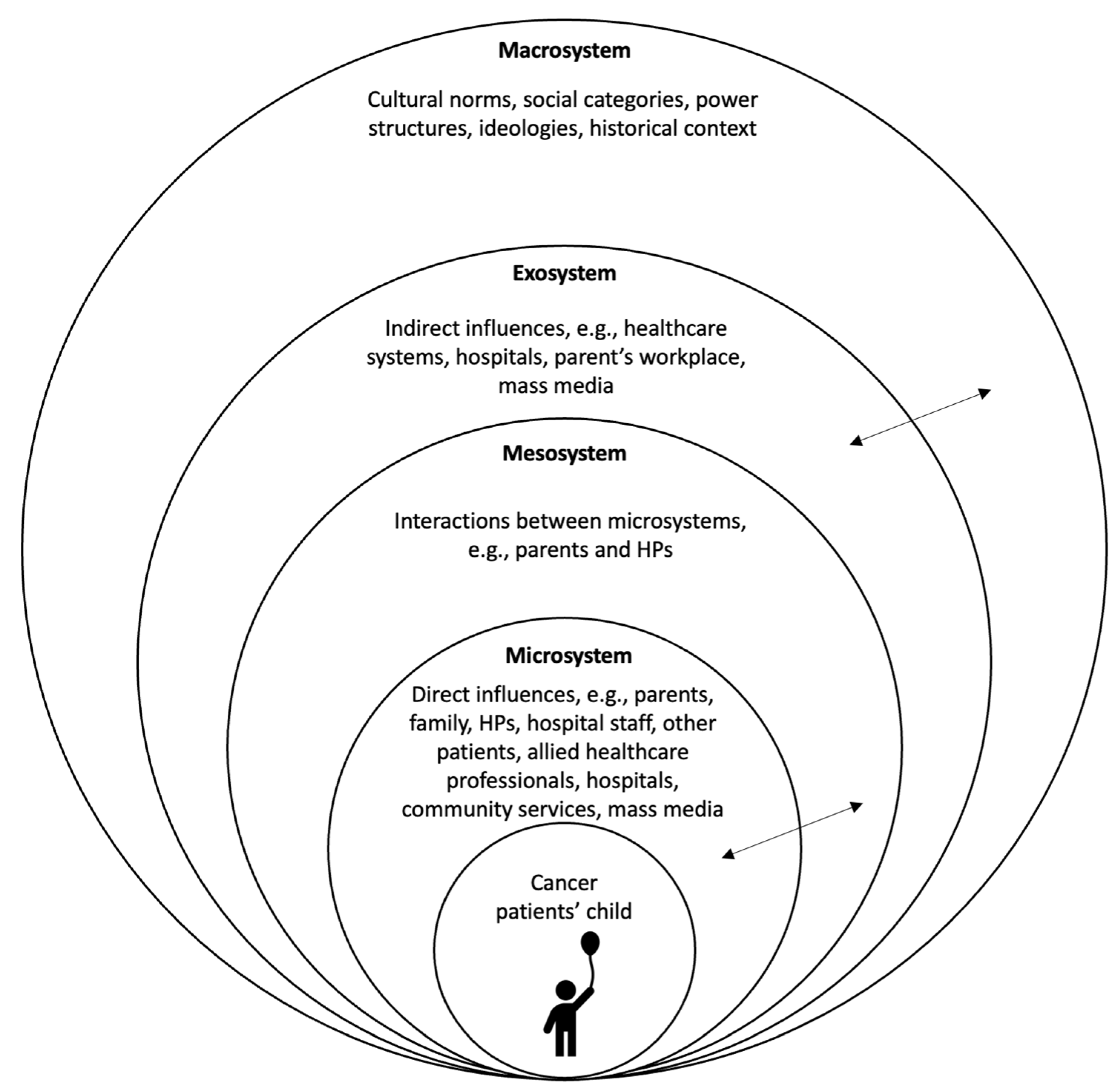

3.4. Explanatory Model: How Children Are Affected by Their Parent’s Cancer Diagnosis

Compromised Social Interactions and Communication Breakdowns

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Recommendations

- Training and education aimed at developing HPs’ communication skills and developmental knowledge.

- The development of a communication tool to be used by HPs to effectively communicate with patients’ children. The new tool might also capture the benefits of technology and integrate the methods used in this study whereby children were encouraged to write and draw about their thoughts and feelings.

- The introduction of routine and standardised screening processes for HPs to detect patients’ children and efficiently refer them on to the appropriate supports and resources that are currently available. Oncology nurses may facilitate this approach while also being supported by the development of a new, or refinement of an existing, screening tool.

- The use of a multidimensional approach to support parents with the practical challenges of a cancer diagnosis. For example, a family support worker or social worker who can assist families from diagnosis onwards.

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) 4125.0—Gender Indicators, Australia. 2018. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4125.0~Sep%202018~Main%20Features~Economic%20Security~4 (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Martini, A.; Morris, J.N.; Jackson, H.M.; Ohan, J.L. The impact of parental cancer on preadolescent children (0–11 years) in Western Australia: A longitudinal population study. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1229–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia; Cancer Series no. 119. Cat. No. CAN 123; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Werner-Lin, A.; Biank, N. Along the Cancer Continuum: Integrating Therapeutic Support and Bereavement Groups for Children and Teens of Terminally Ill Cancer Patients. J. Fam. Soc. Work. 2009, 12, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, B.K.; Armaly, J.; Swieter, E. Impact of Parental Cancer on Children. Anticancer Res. 2017, 37, 4025–4028. [Google Scholar]

- Syse, A.; Aas, G.B.; Loge, J.H. Children and young adults with parents with cancer: A population-based study. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 4, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.E.; Forsythe, L.P.; Reeve, B.B.; Alfano, C.M.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Sabatino, S.A.; Hawkins, N.A.; Rowland, J.H. Mental and Physical Health―Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2012, 21, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.; Turnbull, D.; Preen, D.; Zajac, I.; Martini, A. The psychological, social, and behavioural impact of a parent’s cancer on adolescent and young adult offspring aged 10–24 at time of diagnosis: A systematic review. J. Adolesc. 2018, 65, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, A.; McDonald, F.; Patterson, P.; Dobinson, K.; Allison, K. How does parental cancer affect adolescent and young adult offspring? A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 77, 54–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauskov Graungaard, A.; Roested Bendixen, C.; Haavet, O.R.; Smith-Sivertsen, T.; Mäkelä, M. Somatic symptoms in children who have a parent with cancer: A systematic review. Child. Care Health Dev. 2019, 45, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.J.; Wakefield, C.E.; Antill, G.; Burns, M.; Patterson, P. Supporting children facing a parent’s cancer diagnosis: A systematic review of children’s psychosocial needs and existing interventions. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2017, 26, e12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghofrani, M.; Nikfarid, L.; Nikfarid, L.; Nourian, M.; Nourian, M.; Nasiri, M.; Nasiri, M.; Saiadynia, M.; Saiadynia, M. Levels of unmet needs among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) impacted by parental cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, T. The psychosocial impact of parental cancer on children and adolescents: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology 2007, 16, 101–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylund-Grenklo, T.; Fürst, C.J.; Nyberg, T.; Steineck, G.; Kreicbergs, U. Unresolved grief and its consequences. A nationwide follow-up of teenage loss of a parent to cancer 6–9 years earlier. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3095–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, T.; Forinder, U.; Olsson, M.; Fürst, C.J.; Årestedt, K.; Alvariza, A. Poor Psychosocial Well-Being in the First Year-and-a-Half After Losing a Parent to Cancer—A Longitudinal Study Among Young Adults Participating in Support Groups. J. Soc. Work End Life Palliat. Care 2020, 16, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoppelbein, L.A.; Greening, L.; Elkin, T.D. Risk of posttraumatic stress symptoms: A comparison of child survivors of pediatric cancer and parental bereavement. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2006, 31, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, F.; Lewis, F.M. The adolescent’s experience when a parent has advanced cancer: A qualitative inquiry. Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, G.A.; Visser, A.; van der Graaf, W.T.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Gazendam-donofrio, S.M.; Hoekstra-weebers, J.E. Stress response symptoms in adolescents during the first year after a parent’s cancer diagnosis. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, E.; Bjelland, I.; Fosså, S.D.; Loge, J.H.; Dahl, A. Health-related quality of life in teenagers with a parent with cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2016, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, A.; Huizinga, G.A.; Hoekstra, H.J.; Ta Van Der Graaf, W.; Gazendam-Donofrio, S.M.; Ehm Hoekstra-Weebers, J. Emotional and behavioral problems in children of parents recently diagnosed with cancer: A longitudinal study. Acta Oncol. 2007, 46, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencker, A.; Murray, S.A.; Mason, B.; Rix, B.A.; Bøge, P.; Tjørnhøj-Thomsen, T. Disrupted biographies and balancing identities: A qualitative study of cancer patients’ communication with healthcare professionals about dependent children. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arber, A.; Odelius, A. Experiences of Oncology and Palliative Care Nurses When Supporting Parents Who Have Cancer and Dependent Children. Cancer Nurs. 2018, 41, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, M.; Repo, J.; Wahlberg, K.-E.; Hakko, H.; Räsänen, S. Pilot Evaluation of the Impact of Structured Child-Centered Interventions on Psychiatric Symptom Profile of Parents with Serious Somatic Illness: Struggle for Life Trial. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2012, 30, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helseth, S.; Ulfsaet, N. Having a parent with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2003, 26, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvariza, A.; Lövgren, M.; Bylund-Grenklo, T.; Hakola, P.; Fürst, C.J.; Kreicbergs, U. How to support teenagers who are losing a parent to cancer: Bereaved young adults’ advice to healthcare professionals—A nationwide survey. Pall. Supp. Care 2017, 15, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabiak, B.R.; Bender, C.M.; Puskar, K.R. The impact of parental cancer on the adolescent: An analysis of the literature. Psycho-Oncology 2007, 16, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, G.A.; Visser, A.; Zelders-Steyn, Y.E.; Teule, J.A.; Reijneveld, S.A.; Roodbol, P.F. Psychological impact of having a parent with cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2011, 47, S239–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Rees, C.; Halkett, G. A systematic review of the current interventions available to support children living with parental cancer. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1812–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohan, J.L.; Jackson, H.M.; Bay, S.; Morris, J.N.; Martini, A. How psychosocial interventions meet the needs of children of parents with cancer: A review and critical evaluation. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method; Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design/Urie Bronfenbrenner; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R. School bullying and fitting into the peer landscape: A grounded theory field study. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2018, 39, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliaccio, T.; Raskauskas, J. Bullying as a Social Experience: Social Factors, Prevention and Intervention; Henry Ling Limited: Dorchester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of children with a parent with cancer. Adaption of Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory model from “The Ecology of Cognitive Development”. In Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments; Wozniack, R.H., Fischer, K.W., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K.A. Constructing Grounded Theory/Kathy Charmaz, 2nd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis/Kathy Charmaz; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K.L. Use Your Words: Healing Communication with Children and Teens in Healthcare Settings. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 42, 204. [Google Scholar]

- Zandt, F. Creative Ways to Help Children Manage Big Feelings: A Therapist’s Guide to Working with Preschool and Primary Children; Zandt, F., Barrett, S., Bretherton, L., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, G.B.; Strauss, L.A.; Strutzel, L.E. The Discovery of Grounded Theory Strategies for Qualitative Research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A.L. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory/Juliet Corbin and Anselm Strauss, 3rd ed.; Strauss, A.L., Ed.; Qualitative research; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. The perceived effect of parental cancer on children still living at home: According to oncology health professionals. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2020, 29, e13321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. Supporting parents with cancer: Practical factors which challenge nurturing care (in review).

- Alexander, E.; O’Connor, M.; Halkett, G.K.B. The psychosocial effect of parental cancer: Qualitative interviews with patients’ dependent children. Children 2023, 10, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akesson, B.; D’Amico, M.; Denov, M.; Khan, F.; Linds, W.; Mitchell, C. “Stepping back” as researchers: Addressing ethics in arts-based approaches to working with working with war-affected children in school and community settings. Educ. Res. Soc. Chang. 2014, 3, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Liebman, M.S. Draw and tell: Drawings within the context of child sexual abuse investigations. Arts Psychother. 1999, 26, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, C.; Hershkowitz, I. The Effects of Drawing on Children’s Accounts of Sexual Abuse. Child. Maltreat. 2010, 15, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltman, M.W.M.; Browne, K.D. The assessment of drawings from children who have been maltreated: A systematic review. Child. Abuse Rev. 2002, 11, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Denov, M. Mask-Making and Drawing as Method: Arts-Based Approaches to Data Collection with War-Affected Children. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 160940691983247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, G.M. Drawing together hope: ‘listening’ to militarised children. J. Child. Health Care 2000, 4, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Health and Medical Research Council and Universities Australia. National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research 2007 (Updated 2018); The National Health and Medical Research Council and Universities Australia: Canberra, Australia.

- Mays, N.; Pope, C. Qualitative Research in Health Care, 3rd ed.; Pope, C., Mays, N., Eds.; Blackwell Pub.: Malden, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Q. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccio, F.; Ferrari, F.; Pravettoni, G. When a parent has cancer: How does it impact on children’s psychosocial functioning? A systematic review. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, L.; Rapa, E.; Ziebland, S.; Rochat, T.; Kelly, B.; Hanington, L.; Bland, R.; Yousafzai, A.; Stein, A.; Betancourt, T.; et al. Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition in their parent. Lancet 2019, 393, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, M.; Schofield, P.; Turner, J.; Rauch, P.; Wakefield, C.; Mann, G.B.; Newman, L.; Mason, K.; Gilham, L.; Cannell, J.; et al. Maternal breast cancer and communicating with children: A qualitative exploration of what resources mothers want and what health professionals provide. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafjord, T.; Ytterhus, B. Nurses’ realisation of an inadequate toolbox for approaching adolescents with a parent suffering from cancer: A constructivist grounded theory study. Nord. J. Nurs. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearnley, R.; Boland, J.W. Communication and support from health-care professionals to families, with dependent children, following the diagnosis of parental life-limiting illness: A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Alvariza, A.; Kreicbergs, U.; Sveen, J. Family Communication and Psychological Health in Children and Adolescents Following a Parent’s Death From Cancer. Omega 2021, 83, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, G.; Plumb, C.; Ziebland, S.; Stein, A. Breast Cancer in The Family: Children’s Perceptions of Their Mother’s Cancer and Its Initial Treatment: Qualitative Study. BMJ 2006, 332, 998–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landreth, G.L. Therapeutic Limit Setting in the Play Therapy Relationship. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2002, 33, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, F.; Prezio, E.A.; Panisch, L.S.; Jones, B.L. Factors Affecting Outcomes Following a Psychosocial Intervention for Children When a Parent Has Cancer. J. Child Life 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, J.J.; Perry, J.C.; Robbins, J.M.; Gagné, M.-A.; Nassif, E. Maternal preoccupation and parenting as predictors of emotional and behavioral problems in children of women with breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Sangha, A.; Lister, S.; Wiseman, T. Cancer and the family: Assessment, communication and brief interventions-the development of an educational programme for healthcare professionals when a parent has cancer. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 6, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.; Clavarino, A.; Butow, P.; Yates, P.; Hargraves, M.; Connors, V.; Hausmann, S. Enhancing the capacity of oncology nurses to provide supportive care for parents with advanced cancer: Evaluation of an educational intervention. Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, J.; Kroll, L.; Burke, O.; Lee, J.; Jones, A.; Stein, A. Qualitative Interview Study of Communication Between Parents And Children About Maternal Breast Cancer. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2000, 321, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, V.L.; Lloyd-Williams, M. Information and communication when a parent has advanced cancer. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semple, C.J.; McCaughan, E. Developing and testing a theory-driven e-learning intervention to equip healthcare professionals to communicate with parents impacted by parental cancer. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 41, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauken, M.A.; Farbrot, I.M. The Fuelbox “Young Next of Kin”-A Mixed-Methods Study on the Development and Piloting of a Communication Tool for Adolescents Coping with Parental Cancer or Death. Cancer Nurs. 2021; publish ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Fitch, M.I.; Abramson, T. Information needs of adolescents when a mother is diagnosed with breast cancer. Can. Oncol. Nurs. J. 2007, 17, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.A.; Quill, T. Working with families in palliative care: One size does not fit all. J. Palliat. Med. 2006, 9, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, H.; Schofield, P.; Cockburn, J.; Butow, P.; Tattersall, M.; Turner, J.; Girgis, A.; Bandaranayake, D.; Bowman, D. How to recognize and manage psychological distress in cancer patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2005, 14, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krattenmacher, T.; Kuhne, F.; Ernst, J.; Bergelt, C.; Romer, G.; Moller, B. Parental cancer: Factors associated with children’s psychosocial adjustment—A systematic review. J. Psychosom. Res. 2012, 72, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compas, B.E.; Worsham, N.L.; Ey, S.; Howell, D.C. When Mom or Dad Has Cancer: II. Coping, Cognitive Appraisals, and Psychological Distress in Children of Cancer Patients. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttazzoni, A.; Brar, K.; Minaker, L. Smartphone-based interventions and internalizing disorders in youth: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e16490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiler, M.; Kuso, S.; Nitsch, M.; Simek, M.; Adamcik, T.; Herrero, R.; Etchemendy, E.; Mira, A.; Oliver, E.; Jones Bell, M.; et al. Online interventions to prevent mental health problems implemented in school settings: The perspectives from key stakeholders in Austria and Spain. Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, i71–i79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boydell, K.M.; Hodgins, M.; Pignatiello, A.; Teshima, J.; Edwards, H.; Willis, D. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: A scoping review. J. Can. Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2014, 23, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Ryan-Wenger, N. Children’s adjustment to parental cancer: A theoretical model development. Cancer Nurs. 2007, 30, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, M.; Hakko, H.; Räsänen, S. A Systematic Narrative Review of the Studies on Structured Child-Centred Interventions for Families with a Parent with Cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2010, 19, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J. The role of theory in evidence-based health promotion practice. Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 125–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wight, D.; Wimbush, E.; Jepson, R.; Doi, L. Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.; Brandão, T.; Matos, P.M. Mothers with breast cancer: A mixed-method systematic review on the impact on the parent-child relationship. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, E.A.; Sivesind, D.; Bruera, E. Parents dying of cancer and their children. Pall. Support. Care 2004, 2, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, K.; Ristovski-Slijepcevic, S. Metastatic Cancer and Mothering: Being a Mother in the Face of a Contracted Future. Med. Anthropol. 2011, 30, 629–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, K.E.; Helseth, S.; Darbyshire, P. Parents’ experiences of a Family Support Program when a parent has incurable cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.M.; Check, D.K.; Song, M.-K.; Reeder-Hayes, K.E.; Hanson, L.C.; Yopp, J.M.; Rosenstein, D.L.; Mayer, D.K. Parenting while living with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. Palliat. Med. 2016, 31, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| HPs |

|

| Parents |

|

| Children |

|

| Health Professionals | Number of Participants | n = 15 |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Range | 31–71 years |

| Mean age (SD) | 51.21 (±10.14) years | |

| Gender | Female Male | 80% 20% |

| Role | Cancer Nurse Coordinator | n = 3 |

| Psychosocial support worker or other allied health worker | n = 6 | |

| Nurse practitioner | n = 1 | |

| Clinical/oncological specialist | n = 3 | |

| Clinical psychologist/psychiatrist | n = 2 | |

| Years of relevant experience | ≤10 years | n = 5 |

| ≤20 years | n = 4 | |

| ≤30 years | n = 4 | |

| >30 years | n = 2 | |

| Interview method | Face to face | n = 8 |

| Telephone | n = 7 | |

| Parents | Number of Participants | n = 11 |

| Age | Range Mean age (SD) | 28–52 years 39.7 (±7.44) years |

| Gender | Female Male | 91% or n = 10 9% or n = 1 |

| Health status | Patient | 5 |

| Partner | 6 | |

| Marital status | Married | 9 |

| Separated/Divorced | 1 | |

| Widowed | 1 | |

| Number of children * | 1 child | 4 |

| 2 children | 4 | |

| 3 children | 2 | |

| Age range of children * | 1 to 15 years | |

| Cancer type (primary) * | Bowel cancer | 2 |

| Brain | 1 | |

| Breast | 1 | |

| Burkitts lymphoma | 1 | |

| Lymphoma | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 1 | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma B cell | 1 | |

| Lung | 1 | |

| Oral | 1 | |

| Stage * (at time of interview) | II | 3 |

| III | 1 | |

| IV | 3 | |

| Not reported/remission/deceased | 3 | |

| Ethnicity | Australian | 82% or n = 9 |

| Indonesian | 9% or n = 1 | |

| Malaysian | 9% or n = 1 | |

| Education | Postgraduate | 4 |

| Tertiary | 5 | |

| Other | 2 | |

| Children | Number of Participants | n = 12 |

| Age | Range Mean age (SD) | 5–17 years 9.46 (±3.43) years |

| Gender | Female Male | 58% or n = 7 42% or n = 5 |

| Cultural background | Australian | 75% or n = 9 |

| Indonesian | 17% or n = 2 | |

| Malaysian | 8% or n = 1 | |

| Parent with cancer | Mother | 50% or n = 6 ** |

| Father | 50% or n = 6 ** | |

| Parent’s primary cancer diagnosis *** | Bowel cancer | 2 |

| Brain | 1 | |

| Breast | 1 | |

| Burkitt’s lymphoma | 1 | |

| Lymphoma | 1 | |

| Melanoma | 1 | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma B cell | 1 | |

| Lung | 1 | |

| Oral | 1 | |

| Stage *** (at time of interview) | II | 3 |

| III | 1 | |

| IV | 3 | |

| Not reported/remission/deceased **** | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alexander, E.S.; Halkett, G.K.B.; Lawrence, B.J.; O’Connor, M. A Conceptual Model Depicting How Children Are Affected by Parental Cancer: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach. Children 2023, 10, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091507

Alexander ES, Halkett GKB, Lawrence BJ, O’Connor M. A Conceptual Model Depicting How Children Are Affected by Parental Cancer: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach. Children. 2023; 10(9):1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091507

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlexander, Elise S., Georgia K. B. Halkett, Blake J. Lawrence, and Moira O’Connor. 2023. "A Conceptual Model Depicting How Children Are Affected by Parental Cancer: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach" Children 10, no. 9: 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091507

APA StyleAlexander, E. S., Halkett, G. K. B., Lawrence, B. J., & O’Connor, M. (2023). A Conceptual Model Depicting How Children Are Affected by Parental Cancer: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Approach. Children, 10(9), 1507. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091507