Loneliness, Social Support, Social Trust, and Subjective Wellness in Low-Income Children: A Longitudinal Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is there a significant relationship between the loneliness, social support, social trust and psychological well-being of the children from low-income families?

- Do the feelings of loneliness, social support and social trust of the children from low-income families significantly predict their psychological well-being?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Suggestions

- -

- A comparative study can be planned in terms of loneliness, feelings of social support and social trust, and psychological well-being of children from low-income families and children from high-income families.

- -

- More variables that may affect the psychological well-being of children from low-income families can be examined.

- -

- The research can be conducted again on children living in different regions.

- -

- New studies comparing the loneliness of female and male children between regions can be planned by keeping the sample size higher.

- -

- Conducting comprehensive profile studies with multi-stakeholder research groups that reveal the quantitative and qualitative dimensions of the relationship between early childhood education and care and psychological well-being in low-income families.

- -

- Childhood is a critical period in terms of personality development and spiritual development. In this period, children are negatively affected by conflicts in the family (Öngider, 2013). Therefore, in-depth research on the relationship between marital harmony/couple harmony and children’s psychological well-being levels can be planned.

- -

- With the changing age, information technologies have also entered a new stage and digitalization has accelerated in the education platform as in every platform. In this rapidly digitalizing new world order, relational and experimental studies can be planned on the psychological well-being levels of children with poor economic status, their parents and teachers, and studies with suggestions such as developing practices for the development and protection of psychological health.

- -

- The results of this study showed that social support, social trust, loneliness and psychological well-being are related. Improving the relationships of children from low-income families with their friends, peers and adult generations (mother, father, teachers, relatives) will provide both individual and social benefits. Based on this, creating opportunities and conditions that will increase children’s social support and trust, reduce their feelings of loneliness and increase their psychological well-being can be included in education and government policies.

- -

- As the quality of life decreases, psychological well-being also decreases (Arslan, 2023). Therefore, relevant institutions should increase their efforts to take physical and psychological measures to improve the quality of life of children and families.

- -

- In order to understand children’s emotions and positively support their psychological well-being, training can be prepared for mothers and fathers, who are the most important individuals in children’s development. These trainings can start with low-income families.

- -

- Creating effective platforms and channels for low-income families to obtain information on the acquisition and protection of psychological well-being in early childhood.

- -

- The materials prepared in the process of informing families can be made available to more people on social media information-sharing channels and platforms.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Informed

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. 2023. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/89966.10 (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Fava, N.M.; Li, T.; Burke, S.L.; Wagner, E.F. Resilience in the context of fragility: Development of a multidimensional measure of child wellbeing within the Fragile Families dataset. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 358–367. [Google Scholar]

- Akın, A.; Yılmaz, S.; Özen, Y.; Raba, S.; Özhan, Y. Emotional and Psychological Well-Being Scale for Stirling Children Validity and Reliability of the English Form. In V. Educational Research Congress Oral Presentation; Sakarya University Institute of Educational Sciences Publications: Sakarya, Türkiye, 2016; pp. 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes, M.; Theunissen, N.C.; Brugman, E.; Veen, S.; Verrips, E.G.; Koopman HM Vogels, T.; Wit, J.M.; Verloove-Vanhorick, S.P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the TAPQOL: A health-related quality of life instrument for 1-5-year-old children. Qual. Life Res. 2000, 9, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bunge, E.M.; Essink-Bot, M.L.; Kobussen, M.P.; Suijlekom-Smit, L.W.; Moll, H.A.; Raat, H. Reliability and validity of health status measurement by the TAPQOL. Arch. Dis. Child. 2005, 90, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, S.; Newton, J.; Haynes, J.; Evans, J. Measuring children’s and young people’s wellbeing. In Office of National Statistics Report & BRASS; Cardiff University: Cardiff, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Opree, S.J.; Buijzen, M.; Reijmersdal, E.A.V. Development and validation of the psychological well-being scale for children (PWB-c). Societies 2018, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, E.; Lee, P. Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 61, 9–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schölmerich, A.; Agache, A.; Leyendecker, B.; Ott, N.; Werding, M. Das Wohlergehen von Kindern als Zielgröße politischen Handelns. Vierteljahrsh. Zur Wirtsch. 2014, 83, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statham, J.; Chase, E. Childhood Wellbeing: A Brief Overview; Childhood Wellbeing Research Centre: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagchandani, R.K. Effect of Loneliness on the Psychological Well-being of College Students. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2017, 7, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, C. Loneliness In Older Women: A Review of The Literature. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 27, 795–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peplau, L.A.; Perlman, D. Perspective on loneliness. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Threapy; Peplau, L.A., Perlman, D., Eds.; Wiley Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, D. Loneliness: A life-span, family perspective. In Families and Social Networks; Milardo, R.M., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 190–220. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.S. Reflections on the present state of loneliness research. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1987, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, H.S. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry; W.W. Norton and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Duy, B. The Effect of Group Counseling Based on Cognitive-Behavioral Approach on Loneliness and Dysfunctional Attitudes. Ph.D. Thesis, Ankara University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Eskişehir, Türkiye, 2003. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Körler, Y. Loneliness Levels of Middle School Students in Terms of Various Variables and the Relationship between Loneliness and Social Emotional Learning Skills. Master’s Thesis, Anadolu University, Institute of Educational Sciences, Eskişehir, Türkiye, 2011. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- DiTommaso, E.; Spinner, B. Social and emotional loneliness: A reexamination of Weiss’ typology of loneliness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1997, 22, 417–427. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Baker, M.; Harris, T.; Stephenson, D. Loneliness and socialisolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 10, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, D.A.; Kellner, R.; Moore-West, M. The effects of loneliness: A review of the literature. Compr. Psychiatry 1986, 27, 351–363. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2010, 40, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenberg, K.J. The Relation between Interpersonal Trust and Adjustment: Is Trust Always Good? In Trust in Contemporary Society; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, N.; Stevenson, C.; Costa, S.; Bowe, M.; Wakefield, J.; Kellezi, B.; Wilson, I.; Halder, M.; Mair, E. Community identification, social support, and loneliness: The benefits of social identification for personal well-being. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2021, 60, 1379–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Stajkovic, A.D.; Cho, B. Interpersonal Trust and Emotion as Antecedents of Cooperation: Evidence From Korea 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 41, 1603–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, N.; Pakdaman, S.; Heidari, M.; Tahmassian, K. Developing psychological well-being scale for preschool children. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eris, F.P.; Wolf, M. Combating Loneliness Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness: Social Network Interventions’ Characteristics, Effectiveness, And Applicability. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 26, 591–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A. Loneliness Then and Now. Reflections on Social and Emotional Alienation In Everyday Life. Curr. Psychol. 2004, 23, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.M.; DeLamater, J.D. Support from significant others and loneliness following induced abortion. Soc. Psychiatry 1985, 20, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binetti, M.J.; Kralik, R.; Tkáčová, H.; Roubalova, M. Same and Other: From Plato to Kierkegaard. A reading of a metaphysical thesis in an existencial key. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2021, 12, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, İ. Social support levels of high school students with different academic achievement levels according to some variables. Turk. Psychol. Couns. Guid. J. 2016, 2, 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbina, L.; Mashford-Scott, A.; Church, A.; Tayler, C. Assessment of Wellbeing in Early Childhood Education and Care: Literature Review; Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority: Victoria, Australia, 2015; Available online: www.vcaa.vic.edu.au (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Doğan, T. Social Support and Wellness as Predictors of Psychological Symptoms. Turk. Psychol. Couns. Guid. J. 2016, 3, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Koçer, R.G. Seeking Social Capital in World Values Survey. Unpublished Manuscript. 2014. Available online: https://snis.ch/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/2011_Krishnakumar_Working-paper-3.pdf (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Rotter, J.B. Interpersonal trust, trustworthiness, and gullibility. Am. Psychol. 1980, 35, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralik, R. The Influence of Family and School in Shaping the Values of Children and Young People in the Theory of Free Time and Pedagogy. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 2023, 14, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtinen, V.; Riikonen, E.; Lahtinen, E. Promotion of Mental Health on The European Agenda, Erişim Tarihi: 11 Ağustos 2022. 1997. Available online: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/75859/Promotion.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Desjarlais, R.; Eisenberg, L.; Good, B.; Kleinman, A. World Mental Health: Problems and Priorities in Low-Income Countries; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Turkish Psychiatry Association. Strengthening Mental Health: Concepts, Evidence, Practices: Summary Report. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42940/9241591595-%20tur.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Su, R.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. The Development and Validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2014, 6, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Psychological Well-Being and Mental Health in Youth: Technical Adequacy of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving. Children 2023, 10, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.W.; Tay, L.; Su, R.; Diener, E. Measuring thriving across nations: Examining the measurement equivalence of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2018, 10, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Wang, W.; Han, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, J. Power Decreases Loneliness through Enhanced Social Support: The Moderating Role of Social Exclusion. An. De Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 2021, 37, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thernlund, G.M.; Samuelsson, M. Parental social support and child behaviour problems in different populations and socioeconomic groups: A methodological study. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 36, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.B.; Campbell-Grossman, C.; Kupzyk, K.A.; Brown, S.E.; Yates, B.C.; Hanna, K.M. Social Support and Psychosocial Well-being Among Low-Income, Adolescent, African American, First-Time Mothers. Clin. Nurse Spec. CNS 2016, 30, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Bauer, A.; Stevens, M.; Purtscheller, D.; Knapp, M.; Fonagy, P.; Evans-Lacko, S. Mobilising social support to improve mental health for children and adolescents: A systematic review using principles of realist synthesis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, D.J. Affect-and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 24–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, K.M. Social capital and children’s wellbeing: A critical synthesis of the international social capital literature. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2006, 15, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, A.D.; Gruenfeld, D.H.; Magee, J.C. From power to action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 453–466. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C.; Galinsky, A.D. Power, optimism, and risk-taking. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Roberts, M. Addressing loneliness in later life. Aging Ment. Health 2008, 12, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heritage, Z.; Wilkinson, R.; Grimaud, O.; Pickett, K. Impact of social ties on self reported health in France: Is everyone affected equally? BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 243. [Google Scholar]

| Mean | SD | Skew. | Kurt. | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Loneliness W1 | 7.34 | 3.21 | 0.36 | −0.64 | 0.75 | - | −0.27 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.46 ** |

| 2. Social trust W2 | 8.52 | 2.61 | −0.25 | −0.27 | 0.81 | - | 0.53 ** | 0.47 ** | |

| 3. Social support W2 | 11.51 | 2.83 | −0.79 | 0.15 | 0.74 | - | 0.43 ** | ||

| 4. Subjective well-being W3 | 11.09 | 7.04 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.89 | - |

| Consequent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (Social Trust) | ||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

| X (Loneliness) | –0.122 | 0.06 | –3.48 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 10.14 | 0.51 | 19.93 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.07 F = 12.10; p < 0.001 | ||||

| M2 (Social support) | ||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

| X (Loneliness) | –0.24 | 0.07 | –3.53 | <0.001 |

| Constant | 13.29 | 0.55 | 24.12 | <0.001 |

| R2 = 0.08 F = 12.46; p < 0.001 | ||||

| Y1 (Subjective well-being) | ||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | t | p |

| X (Loneliness) | –0.72 | 0.15 | –4.77 | <0.001 |

| M1 (Social trust) | 0.75 | 0.20 | 3.62 | <0.001 |

| M2 (Social support) | 0.48 | 0.19 | 2.46 | 0.014 |

| Constant | 5.20 | 2.65 | 1.96 | 0.051 |

| R2 = 0.36 F = 28.79; p < 0.001 | ||||

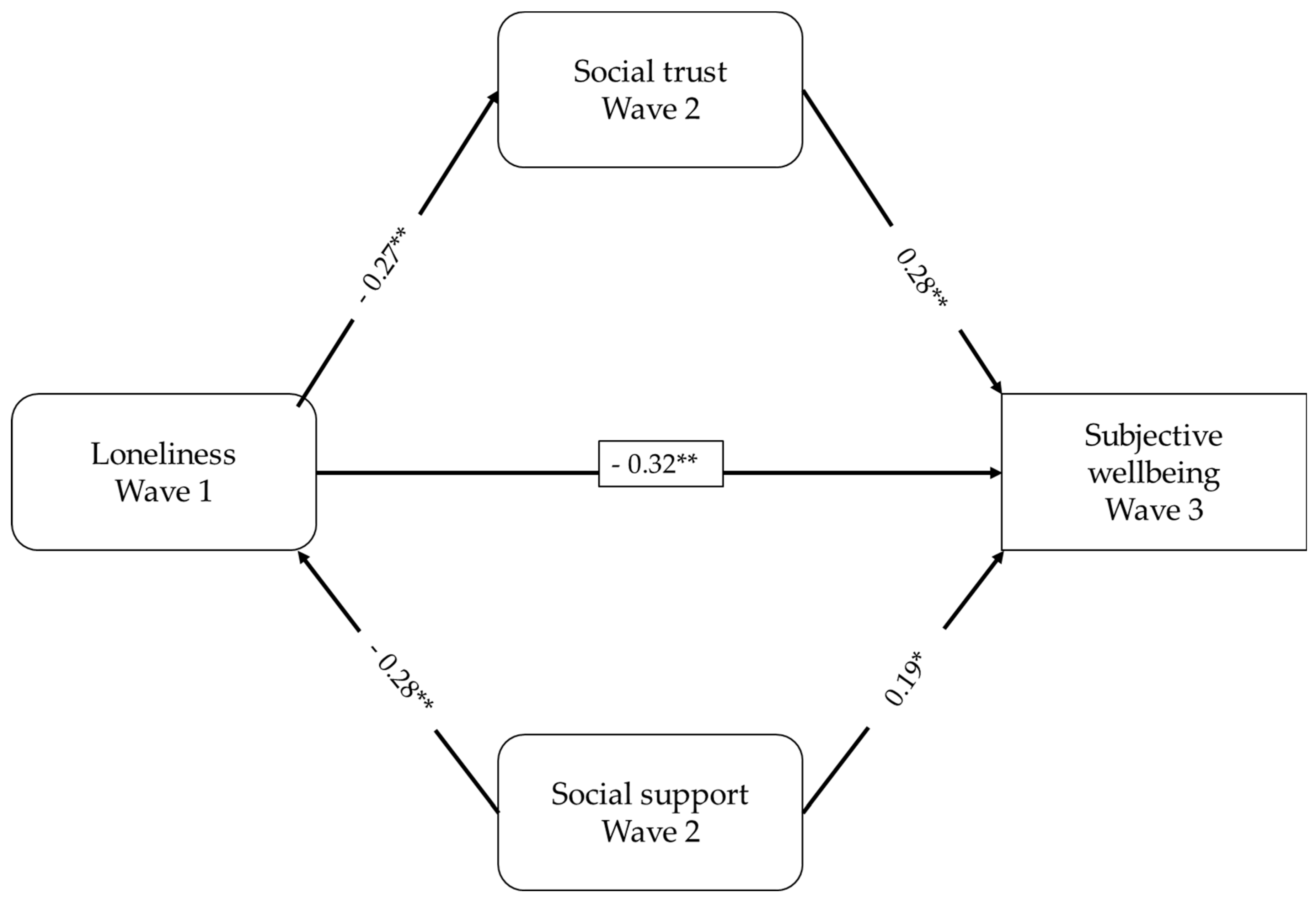

| Standardized indirect effects | ||||

| Paths | Effect | SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Total indirect effect | –0.13 | 0.04 | –0.22 | –0.05 |

| Loneliness → Social trust → Well-being | –0.08 | 0.03 | –0.15 | –0.02 |

| Loneliness → Social support → Well-being | –0.05 | 0.02 | –0.11 | –0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akgül, H.; Güven, A.Z.; Güven, S.; Ceylan, M. Loneliness, Social Support, Social Trust, and Subjective Wellness in Low-Income Children: A Longitudinal Approach. Children 2023, 10, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091433

Akgül H, Güven AZ, Güven S, Ceylan M. Loneliness, Social Support, Social Trust, and Subjective Wellness in Low-Income Children: A Longitudinal Approach. Children. 2023; 10(9):1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091433

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkgül, Hanife, Ahmet Zeki Güven, Sibel Güven, and Müyesser Ceylan. 2023. "Loneliness, Social Support, Social Trust, and Subjective Wellness in Low-Income Children: A Longitudinal Approach" Children 10, no. 9: 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091433

APA StyleAkgül, H., Güven, A. Z., Güven, S., & Ceylan, M. (2023). Loneliness, Social Support, Social Trust, and Subjective Wellness in Low-Income Children: A Longitudinal Approach. Children, 10(9), 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091433