Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect among General Practitioners and Pediatricians in Training: A Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

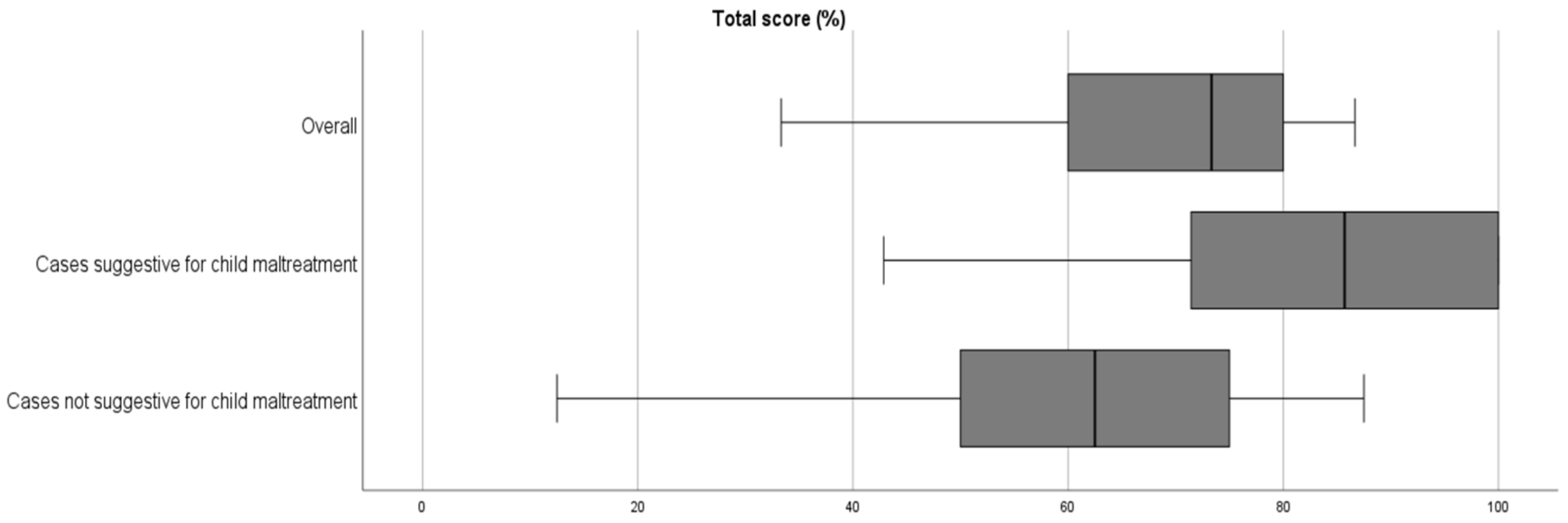

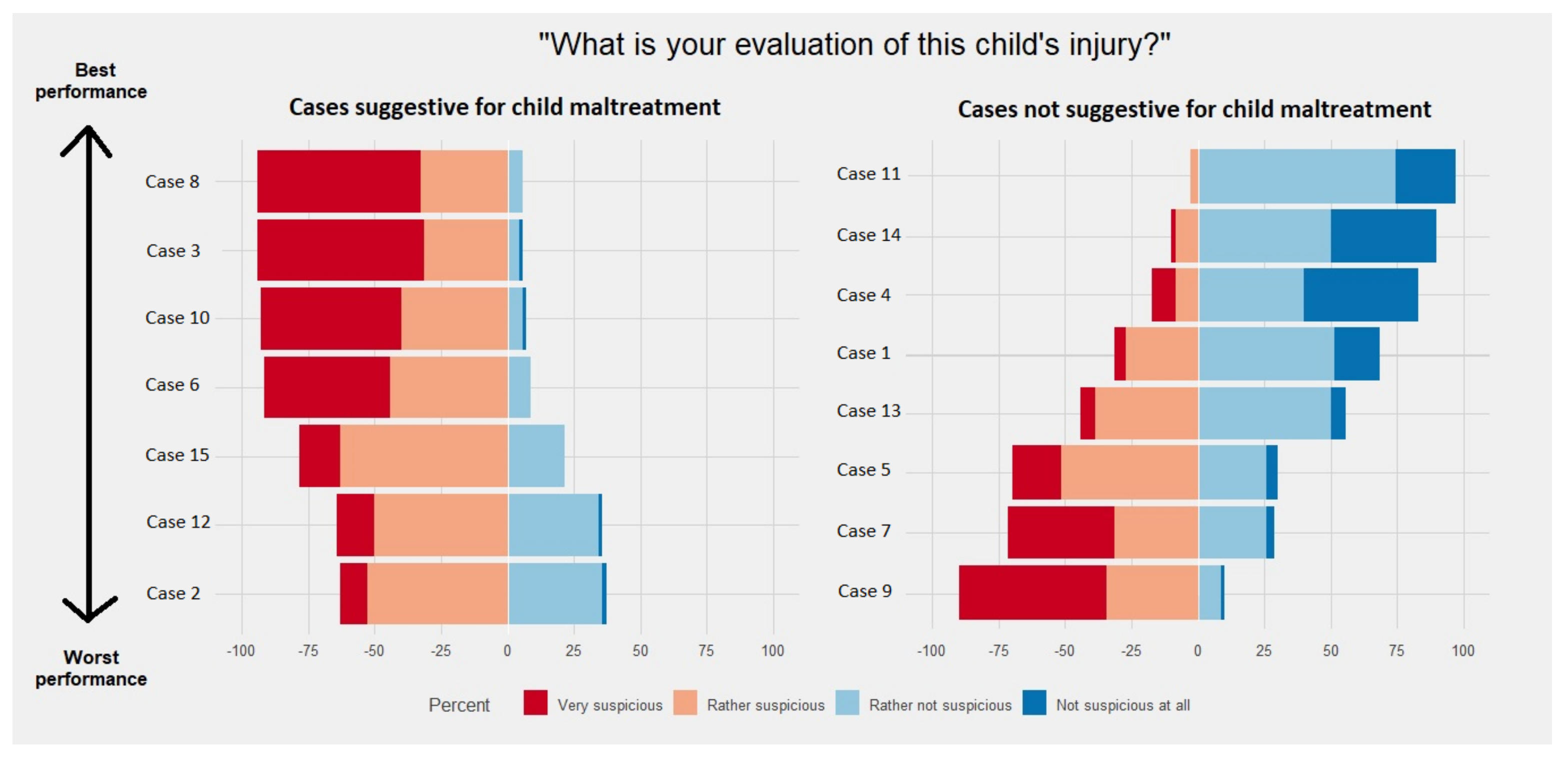

3.2. Performance on the Survey

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pereda, N.; Guilera, G.; Forns, M.; Gómez-Benito, J. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse: A continuation of Finkelhor (1994). Child Abus. Negl. 2009, 33, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Alink, L.R.A.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. The Prevalence of Child Maltreatment across the Globe: Review of a Series of Meta-Analyses. Child Abus. Rev. 2015, 24, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65900 (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Stoltenborgh, M.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013, 48, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statbel. Bevolking per geslacht en leeftijdsgroep voor België, 2010–2020. Available online: https://bestat.statbel.fgov.be/bestat/crosstable.xhtml?view=5fee32f5-29b0-40df-9fb9-af43d1ac9032 (accessed on 2 May 2021).

- Vlaams Agentschap Opgroeien. Het Kind in Vlaanderen 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.opgroeien.be/sites/default/files/documents/kiv2019.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Kind en Gezin. Lokale Teams. Available online: https://www.kindengezin.be/over-kind-en-gezin/lokale-teams/ (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Vlaams Ministerie van Onderwijs en Vorming. Centrum voor Leerlingenbegeleiding (CLB). Available online: https://www.onderwijs.vlaanderen.be/nl/clb (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- Bekkering, G.; Delvaux, N.; Vankrunkelsven, P.; Toelen, J.; Aertgeerts, S.; Crommen, S.; De Bruyckere, P.; Devisch, I.; Lernout, T.; Masschalck, K.; et al. Closing schools for SARS-CoV-2: A pragmatic rapid recommendation. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e000971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarrapport 2020. 2021. Available online: https://1712.be/Portals/1712volw/Files/nieuws/1712%20jaarrapport2020.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Child Focus. Jaarverslag. 2020. Available online: https://childfocus.be/sites/default/files/ra_2020_nl_def_web_0.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Brown, S.M.; Doom, J.R.; Lechuga-Peña, S.; Watamura, S.E.; Koppels, T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, H.-T.; Elliott, L.; Bertrand, S.L. Guidance Note: Protection of Children during Infectious Disease Outbreaks. 2018. Available online: https://alliancecpha.org/en/system/tdf/library/attachments/cp_during_ido_guide_0.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=30184 (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Lawson, M.; Piel, M.H.; Simon, M. Child Maltreatment during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Consequences of Parental Job Loss on Psychological and Physical Abuse Towards Children. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajmil, L.; De Sanmamed, M.-J.F.; Choonara, I.; Faresjö, T.; Hjern, A.; Kozyrskyj, A.L.; Lucas, P.J.; Raat, H.; Séguin, L.; Spencer, N.; et al. Impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6528–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, R.; Widom, C.S.; Browne, K.; Fergusson, D.; Webb, E. Child Maltreatment 1 Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 2009, 373, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.; Kemp, A.; Thoburn, J.; Sidebotham, P.; Radford, L.; Glaser, D.; Macmillan, H.L. Child Maltreatment 2 Recognising and responding to child maltreatment. Lancet 2009, 373, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, R.E.; Byambaa, M.; De, R.; Butchart, A.; Scott, J.; Vos, T. The Long-Term Health Consequences of Child Physical Abuse, Emotional Abuse, and Neglect: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I.; Katz, C.; Andresen, S.; Bérubé, A.; Collin-Vezina, D.; Fallon, B.; Fouché, A.; Haffejee, S.; Masrawa, N.; Muñoz, P.; et al. Child maltreatment reports and Child Protection Service responses during COVID-19: Knowledge exchange among Australia, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Israel, and South Africa. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 116, 105078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.H. Calculating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child abuse and neglect in the U.S. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 118, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlJasser, M.; Al-Khenaizan, S. Cutaneous mimickers of child abuse: A primer for pediatricians. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2008, 167, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.L.; Abshire, T.C.; Anderst, J.D.; Hord, J.; Crouch, G.; Hale, G.; Mueller, B.; Rogers, Z.; Shearer, P.; Werner, E.; et al. Evaluating for suspected child abuse: Conditions that predispose to bleeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e1357–e1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenbaum, A.R.; Donne, J.; Wilson, D.; Dunn, K.W. Intentional burn injury: An evidence-based, clinical and forensic review. Burns 2004, 30, 628–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, B.; Butterfield, R. Common skin and bleeding disorders that can potentially masquerade as child abuse. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C Semin. Med. Genet. 2015, 169, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starling, S.P.; Heisler, K.W.; Paulson, J.F.; Youmans, E. Child abuse training and knowledge: A national survey of emergency medicine, family medicine, and pediatric residents and program directors. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e595–e602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelgais, K.; Pusic, M.; Abdoo, D.; Caffrey, S.; Snyder, K.; Alletag, M.; Balakas, A.; Givens, T.; Kane, I.; Mandt, M.; et al. Child Abuse Recognition Training for Prehospital Providers Using Deliberate Practice. Prehospital Emerg. Care 2020, 25, 822–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, E.G.; Sege, R.; Binns, H.J.; Mattson, C.L.; Christoffel, K.K. Health Care Providers’ Experience Reporting Child Abuse in the Primary Care Setting. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2000, 154, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, B.; Yang, C.; Lehman, E.B.; Mincemoyer, C.; Verdiglione, N.; Levi, B.H. Educating early childhood care and education providers to improve knowledge and attitudes about reporting child maltreatment: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högberg, U.; Eriksson, G.; Högberg, G.; Wahlberg, Å. Parents’ experiences of seeking health care and encountering allegations of shaken baby syndrome: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudd, S.S.; Findlay, J.S. The cutaneous manifestations and common mimickers of physical child abuse. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2004, 18, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swerdlin, A.; Berkowitz, C.; Craft, N. Cutaneous signs of child abuse. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 57, 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettner, M.; Birngruber, C.G.; Niess, C.; Baz-Bartels, M.; Bunzel, L.; Verhoff, M.A.; Lux, C.; Ramsthaler, F. Mongolian spots as a finding in forensic examinations of possible child abuse–implications for case work. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2020, 134, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.G. Does Gender Influence Online Survey Participation? A Record-Linkage Analysis of University Faculty Online Survey Response Behavior. 2008. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED501717 (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Choi, B.C.K.; Pak, A.W.P.; Center for Disease Control and Prevention. A Catalog of Biases in Questionnaires. Prev. Chronic Dis. Public Health Res. Pract. Policy 2005, 2, 19899. [Google Scholar]

| Vignette | Image Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | A mother presents with her 4-year-old daughter in your practice because of a back injury that according to the mother frequently bleeds. It has been there for a few weeks and originated when the girl was ‘with the father’ (divorce with week-to-week arrangement). | The clinical image shows the classical lesion of a pyogenic granuloma: a solitary, red papule above the left scapula on the back of the child. The lesion is not bleeding in the image. |

| Case 2 | A mother comes for a consultation with her 7-month-old daughter because of a rash around the anogenital region. You know that the mother regularly comes and asks for a sickness certificate for her job because of depression. She has become unemployed and is looking for another job. She has four other children, whom you have seen several times at a consultation. You have never seen this child until now. The mother says that this rash was there when she went to change the child’s diaper this morning. According to the mother, the child has had no diarrhea. There is no history of atopy in the family. | The clinical image shows the anogenital region of a female infant with a severe erythematous rash with papulovesicular lesions, fissures, and erosions. It is more severe than the common phenotype of a diaper dermatitis. |

| Case 3 | A grandmother comes with her 13-month-old grandson. The boy has only just started walking a little bit. She is a little worried about the lesion on the ear. She looks after the boy 3 days a week and noticed the injury this morning. According to the mother, the injury has been there since yesterday, but she did not know how it happened. The injury does not go away when pressed on and seems to hurt a little. The child has no fever, there is a normal pulse, and the rest of the clinical examination—except for some eczema spots—is normal. | The clinical image shows a second degree burn in a grid-like pattern on the left earlobe of a toddler. |

| Case 4 | A mother is referred to you by the midwife because of spots on the lower back of a neonate. According to the mother, this has been present for some time and she does not remember any trauma. During the clinical examination, you notice nothing abnormal. The child is of Asian ethnicity. | The clinical image shows the lower back region of a newborn infant with several blueish to blue-grey nummular spots, typical of dermal melanosis. |

| Case 5 | A father comes for a consultation with his 23-month-old son. He is worried because of the injury on his face. The child goes to day-care during the day and they told him that he was bitten by another child. The lesion is sensitive when palpated and the boy, who keeps hiding behind the father, is a bit angry and keeps looking at you suspiciously. | The clinical image shows a toddler with a small bite wound on the left cheek. |

| Case 6 | A couple comes for a consultation with their 3-week-old baby. They are worried because the feeding is not going well, with the baby regularly regurgitatin a lot of milk. According to the parents, the baby seems to have some cramps and always cries in the evening. During the clinical examination, you notice this lesion. Otherwise, there are no eczema lesions and the baby has normal parameters. When you ask the parents how the baby got this lesion, they tell you that they found her this morning with her little leg caught between the bars of the bed. | The clinical image shows both lower legs of an infant with linear reddish lesions in the conformation of a negative imprint of adult digits on the right lower leg. |

| Case 7 | A mother comes in a panic to the consultation with her 18-month-old daughter. Her daughter has just fallen and vomited several times. She fell on the side of her head, in the living room next to the carpet. Immediately after she fell, she started crying. She was never unconscious. You can see these lesions in the face. The rest of the clinical examination is normal. | The clinical image shows the front and side of the face of a toddler with petechiae around the eyes and on the cheeks. |

| Case 8 | A grandmother presents with her 2-year-old grandson because of vomiting and diarrhea for one day. She is worried that he might be dehydrated. At the clinical examination, she sees this non-erasable rash. According to the grandmother, her grandson is a ‘wild child’ who falls and runs into things all the time. | The clinical image shows the left thigh region of a toddler with hand-shaped bruises. |

| Case 9 | A 6-year-old girl comes for a consultation with her mother. The parents are divorced and the girl has just spent a week with her father. The mother is worried because of lesions around the girl’s vagina. The lesions are not painful, and the girl cannot tell much about this abnormality or when it occurred. On further clinical examination, nothing abnormal is observed. | The clinical image shows demarcated white skin lesions, which have an hourglass shape. The skin on the labia majora is atrophic, smooth, and shiny. |

| Case 10 | A mother presents at your consultation with her 6-year-old son because of arunning nose and coughing. During the clinical examination, you notice this injury on the forearm of the boy. The mother does not know when this occurred, and is seeing it for the first time. | The clinical image shows the forearm of a child with a circular second degree burn (crust on the edges of the lesion, diameter 1 cm). |

| Case 11 | A 5-year-old boy comes for a consultation with his parents because of a sudden rash on his limbs. This rash has been present since yesterday, and the parents have the impression it is increasing. The boy has some abdominal pain and had a cold the week before. | The clinical image shows the lower legs of a child with several purpuric lesions (around the ankles and the dorsum of the foot). |

| Case 12 | A father comes with his 3-year-old daughter because of these bruises. The girl is a ‘wild child’ who loves to play and often jumps on the trampoline at home. She has recently started going to school. When asked, the girl had one nosebleed a few weeks ago, but never any gum bleeding. On clinical examination, there are no bruises to be seen anywhere else. | The clinical image shows the upper leg of a child with several linear bruises (four in total, parallel in distribution). |

| Case 13 | A father comes with his son because of red spots in his eye. This morning, the boy woke up with it. You ask the boy how he is doing otherwise (how he feels). He lifts his shoulders and looks at his father. His father then tells you that the boy has been coughing a lot for the past few days and has a sore throat. When asked, the father also says that there have been no nosebleeds or gum bleeding as far as he can remember. On clinical examination, there are no other signs of bleeding and no other lesions. He has no fever. | The clinical image shows the eyes of a child with bilateral conjunctival hemorrhages. |

| Case 14 | A father comes with his 3-year-old daughter. The girl had gone for a walk this morning with her grandfather and the dog when the father received a telephone call from the grandfather saying that the girl suddenly had great pain in her arm. According to the grandfather, she was holding his hand and wanted to jump, whereby the grandfather pulled her arm to prevent her from falling. The girl supports her arm in slight flexion as she walks into the consultation room. She refuses to do anything with her arm. On clinical examination, there is no swelling. She does not allow passive movements. Mild supination of the forearm hurts. The rest of the clinical examination is normal. She has never had anything similar. | The clinical image shows a child on a hospital stretcher with her left arm stretched out parallel to her side, the right arm is in use. |

| Case 15 | A 14-year-old girl presents to your clinic alone. She shows a lesion on her arm that -according to her stsory- has been caused by her stepfather. You know the girl from a very young age but are aware that her mother recently started a new relationship after being divorced many years ago. According to the girl her mother and her new stepfather often have verbal fights Her stpfather is angry with her due to her adolescent and argumentative behaviour and the stress she causes in the household. According to the girl this man often shouts at her, beats her and now has bitten her. | The clinical images shows a circular bruise on the medial side of the forearm. The lesion has a central oval-shaped patch that consists of normal skin. The peripheral part of the lesion shows teeth marks. |

| Categories | N = 70 | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| education | General practitioners in training | 32 | 45.7 |

| Pediatricians in training | 38 | 54.3 | |

| level of education | Junior | 31 | 44.3 |

| Senior | 39 | 55.7 | |

| gender | Male | 8 | 11.4 |

| Female | 61 | 87.1 | |

| X a | 1 | 1.4 | |

| age | <25 | 7 | 10.0 |

| 25–26 | 33 | 47.1 | |

| 27–28 | 16 | 22.9 | |

| 29–30 | 10 | 14.3 | |

| >30 | 4 | 5.7 | |

| number of children | 0 | 65 | 92.9 |

| 1 | 3 | 4.3 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1.4 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Responses (N = 70) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspicious | Not Suspicious | |||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| cases suggestive for child abuse | Case 8 | Hematoma in the shape of a handprint | 66 | (94.3) | 4 | (5.7) |

| Case 3 | Burn in the shape of a grid | 66 | (94.3) | 4 | (5.7) | |

| Case 10 | Cigarette burn | 65 | (92.9) | 5 | (7.1) | |

| Case 6 | Pinch injury | 64 | (91.4) | 6 | (8.6) | |

| Case 15 | Adult-sized bitemark on a 14-year-old girl | 55 | (78.6) | 15 | (21.4) | |

| Case 12 | Linear-shaped hematomas | 45 | (64.3) | 25 | (35.7) | |

| Case 2 | Jacquet’s erythema papulosum posterosivum | 44 | (62.9) | 26 | (37.1) | |

| cases not suggestive for child abuse | Case 11 | Henoch–Schönlein purpura | 2 | (2.9) | 68 | (97.1) |

| Case 14 | Nursemaid’s elbow | 7 | (10.0) | 63 | (90.0) | |

| Case 4 | Dermal melanosis | 12 | (17.1) | 58 | (82.9) | |

| Case 1 | Pyogenic granuloma | 22 | (31.4) | 48 | (68.6) | |

| Case 13 | Subconjunctival hemorrhages after Valsalva-maneuver | 31 | (44.3) | 39 | (55.7) | |

| Case 5 | Pediatric-sized bitemark on a 23-month-old boy | 49 | (70.0) | 21 | (30.0) | |

| Case 7 | Vomiting-induced petechiae | 50 | (71.4) | 20 | (28.6) | |

| Case 9 | Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus | 63 | (90.0) | 7 | (10.0) | |

| Univariate Quadratic Regression | Multivariate Quadratic Regression | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Value | Nagelkerke Pseudo-R2 | Estimate | 95% CI | p-Value | Nagelkerke Pseudo-R2 | |

| education | General practitioners in training | Ref. | Ref. | 0.222 | |||||

| Pediatricians in training | 0.000 | −Inf; 12.972 | 1.000 | 0.000 | −3.810 | −13.231; 5.612 | 0.431 | ||

| level of education | Junior | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Senior | 6.667 | −6.305; 6.667 | 0.054 | 0.067 | 0.952 | −9.851; 11.756 | 0.863 | ||

| gender a | Female | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Male | −13.333 | −13.333; −5.214 | <0.001 | 0.132 | −6.667 | −20.599; 7.266 | 0.352 | ||

| age | Per year increase | 0.556 | −1.120; 2.137 | 0.410 | 0.038 | 1.905 | −0.943; 4.753 | 0.195 | |

| children | No | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Yes | 0.000 | −8.640; +Inf | 1.000 | 0.000 | −5.238 | −17.153; 6.677 | 0.392 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jamaer, M.; Van den Eynde, J.; Aertgeerts, B.; Toelen, J. Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect among General Practitioners and Pediatricians in Training: A Survey. Children 2023, 10, 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091429

Jamaer M, Van den Eynde J, Aertgeerts B, Toelen J. Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect among General Practitioners and Pediatricians in Training: A Survey. Children. 2023; 10(9):1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091429

Chicago/Turabian StyleJamaer, Marjolijn, Jef Van den Eynde, Bert Aertgeerts, and Jaan Toelen. 2023. "Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect among General Practitioners and Pediatricians in Training: A Survey" Children 10, no. 9: 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091429

APA StyleJamaer, M., Van den Eynde, J., Aertgeerts, B., & Toelen, J. (2023). Knowledge of Child Abuse and Neglect among General Practitioners and Pediatricians in Training: A Survey. Children, 10(9), 1429. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091429