Why Do Iranian Preschool-Aged Children Spend too Much Time in Front of Screens? A Preliminary Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Screen-Related Themes in Iranian Families

3.1.1. Temperament/Characteristics of Child

3.1.2. Parental Characteristics

3.1.3. Parental Health Literacy

3.1.4. Family Psychological Atmosphere

3.1.5. Home Structure

3.1.6. Environmental and Social Structure of Society

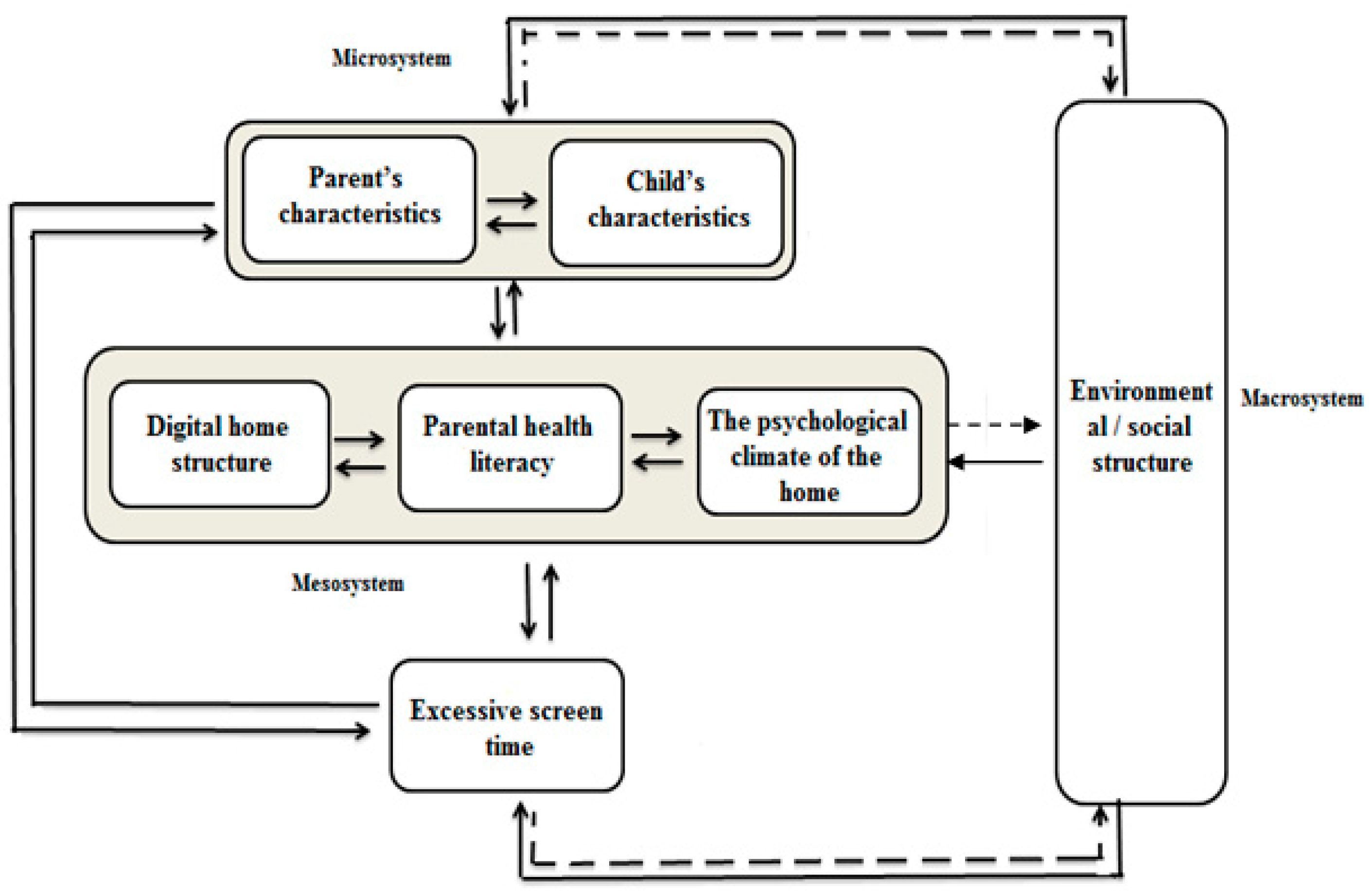

4. Discussion

4.1. The Micro Level

4.2. The Meso Level

4.3. Socio-Cultural Factors

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barber, S.E.; Kelly, B.; Collings, P.J.; Nagy, L.; Bywater, T.; Wright, J. Prevalence, trajectories, and determinants of television viewing time in an ethnically diverse sample of young children from the UK. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moraes Ferrari, G.L.; Pires, C.; Solé, D.; Matsudo, V.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Fisberg, M. Factors associated with objectively measured total sedentary time and screen time in children aged 9–11 years. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.H.; Bedford, R.; Saez De Urabain, I.R.; Karmiloff-Smith, A.; Smith, T.J. Daily touchscreen use in infants and toddlers is associated with reduced sleep and delayed sleep onset. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep46104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.W.; Tsai, A.; Jonas, J.B.; Ohno-Matsui, K.; Chen, J.; Ang, M.; Ting, D.S.W. Digital screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk for a further myopia boom? Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 223, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossiannilsson, E. Increasing Access, Social Inclusion, and Quality through Mobile Learning. Int. J. Adv. Pervasive Ubiquitous Comput. IJAPUC 2018, 10, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daelmans, B.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Lombardi, J.; Black, M.M.; Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.; Dua, T.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Richter, L.M. Early childhood development: The foundation of sustainable development. Lancet 2017, 389, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 12, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, S. What Do We Really Know about Kids and Screens. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 2020, 51, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Screen time and young children: Promoting health and development in a digital world. Paediatr. Child Health 2017, 22, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virgara, R.; Phillips, A.; Lewis, L.; Richardson, M.; Maher, C. Development of Australian physical activity and screen time guidelines for outside school hours care: An international Delphi study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, F.; Roberts, K.C.; Chaput, J.-P.; Goldfield, G.S.; Prince, S.A. Physical activity, screen time and sleep duration: Combined associations with psychosocial health among Canadian children and youth. Health Rep. 2020, 31, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cabré-Riera, A.; Torrent, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Vrijheid, M.; Cardis, E.; Guxens, M. Telecommunication devices use, screen time and sleep in adolescents. Environ. Res. 2019, 171, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, R.; Fang, H.; Chen, M.; Hu, X.; Cao, Y.; Yang, F.; Xia, K. Screen time and sleep disorder in preschool children: Identifying the safe threshold in a digital world. Public Health 2020, 186, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.-Y.; Huang, L.-H.; Schmid, K.L.; Li, C.-G.; Chen, J.-Y.; He, G.-H.; Liu, L.; Ruan, Z.-L.; Chen, W.-Q. Associations between screen exposure in early life and myopia amongst Chinese preschoolers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pouretemad, H.; Shervin-Badv, R. Screen-Time Predicts Sleep and Feeding Problems in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Symptoms Under the Age of Three. Q. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 15, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Martín, D.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Ruiz-Tendero, G.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; Puertas-Molero, P. The Relationships between Physical Activity, Screen Time and Sleep Time According to the Adolescents’ Sex and the Day of the Week. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjeti-Madan, V.N.; Ranganathan, P. Impact of Screen Time on Children’s Development: Cognitive, Language, Physical, and Social and Emotional Domains. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2023, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzola, E.; Spina, G.; Ruggiero, M.; Memo, L.; Agostiniani, R.; Bozzola, M.; Corsello, G.; Villani, A. Media devices in pre-school children: The recommendations of the Italian pediatric society. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pouretemad, H.; Khosrowabadi, R.; Fathabadi, J.; Nikbakht, S. Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence for parent training in young children with autism symptoms and excessive screen-time. Asian J. Psychiatry 2019, 45, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pouretemad, H.R.; Khosrowabadi, R.; Fathabadi, J.; Nikbakht, S. Effects of parent–child interaction training on children who are excessively exposed to digital devices: A pilot study. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2019, 54, 408–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Pouretemad, H.R.; Khosrowabadi, R.; Fathabadi, J.; Nikbakht, S. Parent–child interaction effects on autism symptoms and EEG relative power in young children with excessive screen-time. Early Child Dev. Care 2021, 191, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglic, N.; Viner, R.M. Effects of screentime on the health and well-being of children and adolescents: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e023191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lissak, G. Adverse physiological and psychological effects of screen time on children and adolescents: Literature review and case study. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motamed-Gorji, N.; Qorbani, M.; Nikkho, F.; Asadi, M.; Motlagh, M.E.; Safari, O.; Arefirad, T.; Asayesh, H.; Mohammadi, R.; Mansourian, M. Association of screen time and physical activity with health-related quality of life in Iranian children and adolescents. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.-C.; Lai, J.S.; Yip, J. Influences of smartphone and computer use on health-related quality of life of early adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, A.O.; Sari, E.; Yucel, H.; Oğuz, M.M.; Polat, E.; Acoglu, E.A.; Senel, S. Exposure to and use of mobile devices in children aged 1–60 months. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2019, 178, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabali, H.K.; Irigoyen, M.M.; Nunez-Davis, R.; Budacki, J.G.; Mohanty, S.H.; Leister, K.P.; Bonner, R.L. Exposure and use of mobile media devices by young children. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júdice, P.B.; Magalhães, J.P.; Rosa, G.; Henriques-Neto, D.; Hetherington-Rauth, M.; Sardinha, L.B. Sensor-based physical activity, sedentary time, and reported cell phone screen time: A hierarchy of correlates in youth. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020, 10, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebremariam, M.K.; Henjum, S.; Terragni, L.; Torheim, L.E. Correlates of screen time and mediators of differences by parental education among adolescents. BMC Pediatr. 2020, 20, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, S.; Sarlak, S.; Ayoubi, S. Develop and Evaluation of Psychometric Properties of Smartphone and Tablet Addiction Questionnaire- Parent Version in Elementary School Students and Its Relationship with Parenting Style. J. Fam. Res. 2021, 17, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalani, B.; Azadfallah, P.; Farahani, H. Correlates of screen time in children and adolescents: A systematic review study. J. Mod. Rehabil. 2021, 15, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafarian, N.; Motlagh, M.E.; Heshmat, R.; Karimi, S.; Mansourian, M.; Mohebpour, F.; Qorbani, M.; Kelishadi, R. Factors associated with screen time in Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shalani, B. Analysis and Review of the Iranian Children’s Overuse in Virtual Space and Development of a Preparatory Program to Optimize Their Use of New Media. Ph.D. Thesis, Tarbiat Modares, Tehran, Iran, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- English, T.; John, O.P.; Srivastava, S.; Gross, J.J. Emotion regulation and peer-rated social functioning: A 4-year longitudinal study. J. Res. Personal. 2012, 46, 780–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaverdi, T.; Shaverdi, S. Children, adult and mothers’ view about the social impacts of computer games. J. Iran. Cult. Res. 2009, 2, 47–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jari, M.; Qorbani, M.; Motlagh, M.E.; Heshmat, R.; Ardalan, G.; Kelishadi, R. A nationwide survey on the daily screen time of Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 224. [Google Scholar]

- Hovsepian, S.; Kelishadi, R.; Motlagh, M.E.; Kasaeian, A.; Shafiee, G.; Arefirad, T.; Najafi, F.; Khoramdad, M.; Asayesh, H.; Heshmat, R. Level of physical activity and screen time among Iranian children and adolescents at the national and provincial level: The CASPIAN-IV study. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2016, 30, 422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V.; Terry, G.; Hayfield, N. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health and Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 843–860. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.; Choi, K.; Resor, J.; Smith, C.L. Why do parents use screen media with toddlers? The role of child temperament and parenting stress in early screen use. Infant Behav. Dev. 2021, 64, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J.S.; Peacock-Chambers, E.; Zuckerman, B.; Silverstein, M. Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatr. 2016, 170, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, A.I.; Beyens, I. The role of sleep in the relation between young children’s mobile media use and effortful control. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 36, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.; Lanier, P.; Wong, P.Y.J. Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 37, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Singletary, B.; Jiang, H.; Justice, L.M.; Lin, T.-J.; Purtell, K.M. Child behavior problems during COVID-19: Associations with parent distress and child social-emotional skills. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2022, 78, 101375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahithya, B.; Raman, V. Parenting style, parental personality, and child temperament in children with anxiety disorders—A clinical study from India. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vafaeenejad, Z.; Elyasi, F.; Moosazadeh, M.; Shahhosseini, Z. Psychological factors contributing to parenting styles: A systematic review. F1000Research 2019, 7, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. In Child Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1984; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Eyimaya, A.O.; Irmak, A.Y. Relationship Between Parenting Practices and Children’s Screen Time during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2021, 56, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaylan, N.; Yalçın, S.S.; Nergiz, M.E.; Yıldız, D.; Oflu, A.; Tezol, Ö.; Çiçek, Ş.; Foto-Özdemir, D. Associations between parenting styles and excessive screen usage in preschool children. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2021, 56, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Geest, K.; Mérelle, S.; Rodenburg, G.; Van de Mheen, D.; Renders, C. Cross-sectional associations between maternal parenting styles, physical activity and screen sedentary time in children. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, L.; van Grieken, A.; Renders, C.M.; HiraSing, R.A.; Raat, H. Parenting style, the home environment, and screen time of 5-year-old children; the ‘be active, eat right’ study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arundell, L.; Parker, K.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Veitch, J. Home-based screen time behaviors amongst youth and their parents: Familial typologies and their modifiable correlates. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niermann, C.Y.; Gerards, S.M.; Kremers, S.P. Conceptualizing family influences on children’s energy balance-related behaviors: Levels of Interacting Family Environmental Subsystems (The LIFES Framework). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Peijie, C.; Kun, W.; Tingran, Z.; Hengxu, L.; Jinxin, Y.; Wenyun, L.; Jiong, L. The Influence of Family Sports Attitude on Children’s Sports Participation, Screen Time, and Body Mass Index. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 697358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel-Berges, M.L.; Santaliestra-Pasias, A.M.; Mouratidou, T.; Flores-Barrantes, P.; Androutsos, O.; De Craemer, M.; Galcheva, S.; Koletzko, B.; Kulaga, Z.; Manios, Y. Parental perceptions, attitudes and knowledge on European preschool children’s total screen time: The ToyBox-study. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 30, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delisle Nyström, C.; Abbott, G.; Cameron, A.J.; Campbell, K.J.; Löf, M.; Salmon, J.; Hesketh, K.D. Maternal knowledge explains screen time differences 2 and 3.5 years post-intervention in INFANT. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 3391–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, S.N.; Teh, L.H.; Tay, W.R.; Anantharaman, S.; van Dam, R.M.; Tan, C.S.; Chua, H.L.; Wong, P.G.; Müller-Riemenschneider, F. Sociodemographic, home environment and parental influences on total and device-specific screen viewing in children aged 2 years and below: An observational study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e009113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Määttä, S.; Kaukonen, R.; Vepsäläinen, H.; Lehto, E.; Ylönen, A.; Ray, C.; Erkkola, M.; Roos, E. The mediating role of the home environment in relation to parental educational level and preschool children’s screen time: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, K.L.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A.; Hinkley, T.; Cliff, D.P.; Okely, A.D.; Hesketh, K.D. Sitting and screen time outside school hours: Correlates in 6-to 8-year-old children. J. Phys. Act. Health 2019, 16, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, M.; Sekine, M.; Tatsuse, T. Parental internet use and lifestyle factors as correlates of prolonged screen time of children in Japan: Results from the super Shokuiku school project. J. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, K.L.; Hinkley, T.; Salmon, J.; Hnatiuk, J.A.; Hesketh, K.D. Do the correlates of screen time and sedentary time differ in preschool children? BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, P.A.; Liu, H.; Umberson, D. Family Relationships and Well-Being. Innov. Aging 2017, 1, igx025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisson, S.B.; Broyles, S.T. Social-ecological correlates of excessive TV viewing: Difference by race and sex. J. Phys. Act. Health 2012, 9, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, S.J.; Pajulo, M.; Vinzce, L.; Raittila, S.; Sourander, J.; Kalland, M. Parent relationship satisfaction and reflective functioning as predictors of emotional availability and infant behavior. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 30, 1214–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neppl, T.K.; Wedmore, H.; Senia, J.M.; Jeon, S.; Diggs, O.N. Couple interaction and child social competence: The role of parenting and attachment. Soc. Dev. 2019, 28, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halford, W.K.; Rhoades, G.; Morris, M. Effects of the parents’ relationship on children. In Handbook of Parenting and Child Development across the Lifespan; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, G.C.; Norton, A.M.; Durtschi, J.A. Early romantic relationships linked with improved child behavior 8 years later. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 37, 717–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K.P.; Lee, S.J. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, responsiveness, and child wellbeing among low-income families. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorek, Y. Grandparental and overall social support as resilience factors in coping with parental conflict among children of divorce. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassul, C.; Corish, C.A.; Kearney, J.M. Associations between home environment, children’s and parents’ characteristics and children’s TV screen time behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaq, A.; Ashraf, H.; Iftikhar, S.; Baig-Ansari, N. Parental perception on screen time and psychological distress among young children. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsh-Yechezkel, G.; Mandelzweig, L.; Novikov, I.; Bar-Yosef, N.; Livneh, I.; Oren, M.; Waysberg, R.; Sadetzki, S. Mobile phone-use habits among adolescents: Predictors of intensive use. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2019, 22, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, R.P. Mental health considerations in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, N.; Pal, A. Impact of digital surge during COVID-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Feng, J.; Huang, W.; Wong, S.H. Associations between weather conditions and physical activity and sedentary time in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Place 2021, 69, 102546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Stappen, V.; Latomme, J.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Lateva, M.; Chakarova, N.; Kivelä, J.; Lindström, J.; Androutsos, O.; González-Gil, E. Barriers from multiple perspectives towards physical activity, sedentary behaviour, physical activity and dietary habits when living in low socio-economic areas in Europe. The Feel4Diabetes Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Decker, E.; De Craemer, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Wijndaele, K.; Duvinage, K.; Koletzko, B.; Grammatikaki, E.; Iotova, V.; Usheva, N.; Fernández-Alvira, J. Influencing factors of screen time in preschool children: An exploration of parents’ perceptions through focus groups in six European countries. Obes. Rev. 2012, 13, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, N.; Harris, N.; Downes, M. Preschool children’s preferences for sedentary activity relates to parent’s restrictive rules around active outdoor play. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, K.J.; Van Fossen, C.; Cotto-Maisonet, J.; Palmer, E.N.; Eneli, I. Mothers’ Perspectives on the development of their preschoolers’ dietary and physical activity behaviors and parent-child relationship: Implications for pediatric primary care physicians. Clin. Pediatr. 2017, 56, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Daniels, L.; Murray, N.; White, K.; Walsh, A. Mothers’ perceptions about introducing complementary feeding at 6 months: Identifying critical belief-based targets for promoting adherence to current infant feeding guidelines. J. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.; Thomson, C.E.; White, K.M. Promoting active lifestyles in young children: Investigating mothers’ decisions about their child’s physical activity and screen time behaviours. Matern. Child Health J. 2013, 17, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarma, T.; Koski, P.; Löyttyniemi, E.; Lagström, H. The factors associated with toddlers’ screen time change in the STEPS Study: A two-year follow-up. Prev. Med. 2016, 84, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaala, S.E.; Hornik, R.C. Predicting US infants’ and toddlers’ TV/video viewing rates: Mothers’ cognitions and structural life circumstances. J. Child. Media 2014, 8, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, M.H. Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting 2012, 12, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segijn, C.M.; Kononova, A. Audience, media, and cultural factors as predictors of multiscreen use: A comparative study of the Netherlands and the United States. Int. J. Commun. 2018, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

| Codes | Subtheme | Theme |

|---|---|---|

| Empathetic child | Adjusted child | Temperament/characteristics of the child |

| Good communication | ||

| Ability to play alone | ||

| Interaction ability | ||

| Angry child | Maladjusted child | |

| Anxious child | ||

| Mischievous/naughty child | ||

| Not interested in playing | ||

| Irregular sleeping and eating habits | ||

| Level of fatigue | The energy level and mobility rate | |

| Level of mobility | ||

| Online playing | Child interests and digital capabilities | |

| Using the Internet | ||

| Playing digital games | ||

| Using different apps | ||

| Interest in different media | ||

| Eating meals and snacks with TV | ||

| Limiting mother | Helicopter parent | Parental characteristics |

| Controlling parent | ||

| Self-sacrificing mother | ||

| Over-responding to child’s wishes | ||

| Self-respect | Mature parent | |

| Patient father | ||

| Responsible mother | ||

| Playing with the child | ||

| Well-informed mother | ||

| Joint activity with the child | ||

| Strict parent | Immature parent | |

| Bored mother | ||

| Selfish mother | ||

| Clingy mother | ||

| Appeasing mother | ||

| Punishing mother | ||

| Indulgent mother | ||

| Neglecting the child | ||

| Perfectionist mother | ||

| Non-supportive mother | ||

| Irresponsible and negligent father | ||

| Not respecting the personality of the child | ||

| Not interested in children | Narcissistic parent | |

| Priority of Job to child | ||

| Priority of relationships to child | ||

| Not a priority | Parenting pattern | Parental health literacy |

| Overuse | ||

| Managed usage | ||

| Explain to the child | ||

| Excessive use by parents | ||

| Don’t use it in front of the child | ||

| Install the games for the child | ||

| Playing digital games with the child | ||

| Working with DD at home | ||

| Not playing with the child | Self-centered parenting | |

| Entertaining the child with DD | ||

| Learning and teaching | Thoughtful parenting | |

| Physical and psychological damage | ||

| Restrictions and supervision | Monitoring standards | |

| Lack of criteria for buying CDs (CD: Compact Disc) | ||

| No limit to the time and content | ||

| Absent parent | Presence of parents | Family psychological atmosphere |

| Busy parent | ||

| Not responding parent | ||

| Not cooperating with parents | Different family norms within extended family | |

| No restrictions in extended family | ||

| Migration | The loneliness of the child | |

| No playmate/ friend | ||

| Positive interaction | Parent–parent interaction | |

| Reduced interaction | ||

| Non-intimate relationships | ||

| Cold relationship | ||

| Reduced interaction | Parent–child interaction | |

| Appropriate interaction | ||

| Inappropriate interaction | ||

| Personality conflicts | Congruency/Incongruency of parents with each other | |

| Cultural differences | ||

| Harmony in child rearing | ||

| Contradiction in education | ||

| Limited space | Physical space of the home | Home structure |

| A yard at home | ||

| Arrangement of home equipment | ||

| Variety of DD | Abundance and accessibility of DD | |

| Too many DD | ||

| Availability of DD | ||

| Using it in front of the child | ||

| Use by others | Background TV | |

| TV being on while playing | ||

| TV being on without purpose | ||

| Waiting for favorite TV program | ||

| Tablet ownership | Child’s ownership of DD | |

| Mobile phone ownership | ||

| TV in the children’s bedroom | ||

| Ownership of SIM card with internet | ||

| Doing work at home during COVID-19 | Unexpected events and imposed conditions | Environmental/social structure of society |

| Decreased social communication during COVID-19 | ||

| Staying at home | Climate condition | |

| Less communication with peers | ||

| Society norms | Environmental requests | |

| Special situations | ||

| Cultural facilities | Facilities and security of the living environment | |

| Mistrust of neighbors | ||

| Feeling insecure in living area | ||

| Distance to recreational facilities | ||

| Watching cartoons | Kindergarten | |

| kindergarten rules | ||

| Digital content production | ||

| No peers | Peer group’s role | |

| Digital games with peers | ||

| Peer influence on children’s requests |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shalani, B.; Azadfallah, P.; Farahani, H.; Brand, S. Why Do Iranian Preschool-Aged Children Spend too Much Time in Front of Screens? A Preliminary Qualitative Study. Children 2023, 10, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071193

Shalani B, Azadfallah P, Farahani H, Brand S. Why Do Iranian Preschool-Aged Children Spend too Much Time in Front of Screens? A Preliminary Qualitative Study. Children. 2023; 10(7):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071193

Chicago/Turabian StyleShalani, Bita, Parviz Azadfallah, Hojjatollah Farahani, and Serge Brand. 2023. "Why Do Iranian Preschool-Aged Children Spend too Much Time in Front of Screens? A Preliminary Qualitative Study" Children 10, no. 7: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071193

APA StyleShalani, B., Azadfallah, P., Farahani, H., & Brand, S. (2023). Why Do Iranian Preschool-Aged Children Spend too Much Time in Front of Screens? A Preliminary Qualitative Study. Children, 10(7), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10071193