Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Heart Conditions in Children: Insight from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

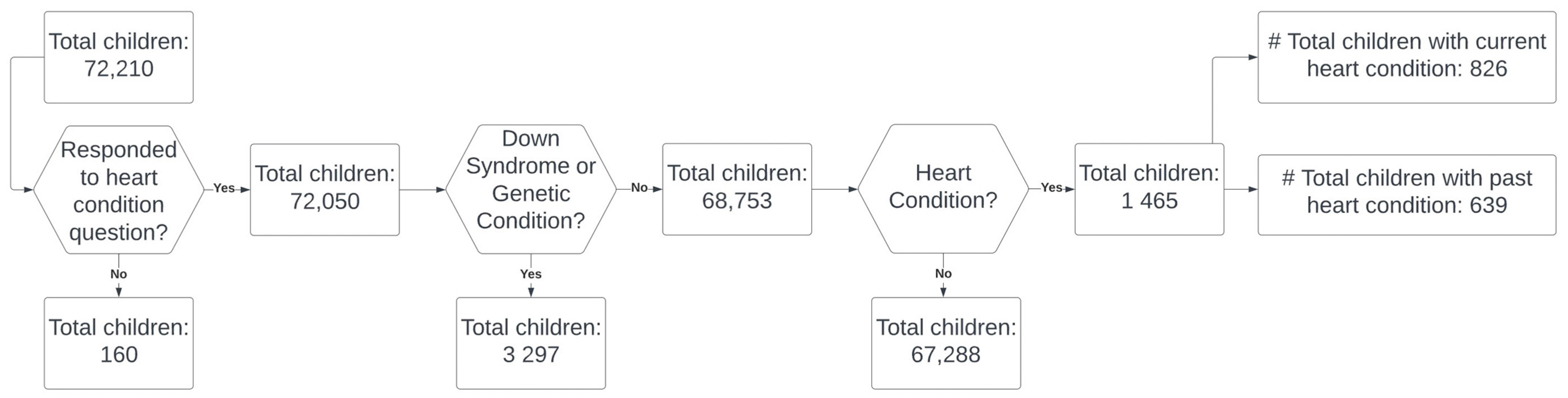

2.1. Data Source and Study Population

2.2. Adverse Childhood Experiences

2.3. Study Outcomes

2.4. Demographic Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Missingness

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Distributions

3.2. ACEs and Heart Conditions

3.3. ACEs and Severity of Heart Conditions

3.4. ACEs and Caregivers Reported Overall Health Status

4. Discussion

Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Koss, M.P.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, D.W.; Kaufman, J. Adverse childhood experiences in children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2018, 31, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, G.Y.; Pillai, N.; Trivedi, R.G. Adverse Childhood Experiences & mental health—The urgent need for public health intervention in India. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62, E728–E735. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K.; Bellis, M.A.; Hardcastle, K.A.; Sethi, D.; Butchart, A.; Mikton, C.; Jones, L.; Dunne, M.P. The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, L.C.; Frankfurter, C.; Cooper, M.; Lay, C.; Maunder, R.; Farkouh, M.E. Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences With Cardiovascular Disease Later in Life: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagattini, A. Children’s well-being and vulnerability. Ethic-Soc. Welf. 2019, 13, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.; Arora, S.K.; Chaturvedi, S.; Gupta, P. Defining and measuring vulnerability in young people. Indian J. Community Med. 2015, 40, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-Y.; Riehle-Colarusso, T.; Yeung, L.F.; Smith, C.; Farr, S.L. Children with Heart Conditions and Their Special Health Care Needs—United States, 2016. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasuski, R.A.; Bashore, T.M. Congenital Heart Disease Epidemiology in the United States: Blindly Feeling for the Charging Elephant. Circulation 2016, 134, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, C.; O’Leary, D.D.; Cairney, J.; Wade, T.J. Adverse childhood experiences and the cardiovascular health of children: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatr. 2013, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Jimenez, M.P.; Roberts, C.T.F.; Loucks, E.B. The Role of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Review with Emphasis on Plausible Mechanisms. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2015, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschênes, S.S.; Kivimaki, M.; Schmitz, N. Adverse Childhood Experiences and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Adulthood: Examining Potential Psychological, Biological, and Behavioral Mediators in the Whitehall II Cohort Study. J. Am. Hearth Assoc. 2021, 10, e019013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, A.L.; Nelson, C.A. Brain Development and the Role of Experience in the Early Years. Zero three 2009, 30, 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel, P.M.; Pereira, L.O.; Silveira, P.P.; Meaney, M.J. Early environmental influences on the development of children’s brain structure and function. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2019, 61, 1127–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xerxa, Y.; Delaney, S.W.; Rescorla, L.A.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; White, T.; Verhulst, F.C.; Muetzel, R.L.; Tiemeier, H. Association of Poor Family Functioning From Pregnancy Onward With Preadolescent Behavior and Subcortical Brain Development. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerker, B.D.; Zhang, J.; Nadeem, E.; Stein, R.E.; Hurlburt, M.S.; Heneghan, A.; Landsverk, J.; McCue Horwitz, S. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Mental Health, Chronic Medical Conditions, and Development in Young Children. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 15, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisanti, A.J. Parental stress and resilience in CHD: A new frontier for health disparities research. Cardiol. Young- 2018, 28, 1142–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Survey of Children’s Health—Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health. 2020. Available online: https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/NSCH (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Elmore, A.L.; Crouch, E. The Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences With Anxiety and Depression for Children and Youth, 8 to 17 Years of Age. Acad. Pediatr. 2020, 20, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuri, F.; Nash, M.C.; Bakour, C.; Kip, K. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Headaches Among Children: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Headache 2020, 60, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, M.K.; Romero, T.; Szilagyi, P.G. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Association With Pediatric Asthma Severity in the 2016-2017 National Survey of Children’s Health. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 21, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences, Nationally, by State, and by Race or Ethnicity. 2018. Available online: https://www.childtrends.org/publications/prevalence-adverse-childhood-experiences-nationally-state-race-ethnicity (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Miao, Q.; Dunn, S.; Wen, S.W.; Lougheed, J.; Reszel, J.; Venegas, C.L.; Walker, M. Neighbourhood maternal socioeconomic status indicators and risk of congenital heart disease. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyvandi, S.; Baer, R.J.; Chambers, C.D.; Norton, M.E.; Rajagopal, S.; Ryckman, K.K.; Moon-Grady, A.; Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; Steurer, M.A. Environmental and Socioeconomic Factors Influence the Live-Born Incidence of Congenital Heart Disease: A Population-Based Study in California. J. Am. Hearth Assoc. 2020, 9, e015255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuczkowski, K.M. The effects of drug abuse on pregnancy. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 19, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Yu, D.; Yang, L.; Da, M.; Wang, Z.; Lin, Y.; Ni, B.; Wang, S.; Mo, X. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy and congenital heart defects in offspring: Review of the current evidence. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zierler, S. Maternal drugs and congenital heart disease. Obstetrics & Gynecology 1985, 65, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R.P.-S.; de Wit, M.L.; McKeown, D. The impact of poverty on the current and future health status of children. Paediatr. Child Health 2007, 12, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, K.L.; Merrill, S.M.; Gill, R.; Miller, G.E.; Gadermann, A.M.; Kobor, M.S. Society to cell: How child poverty gets “Under the Skin” to influence child development and lifelong health. Dev. Rev. 2021, 61, 100983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Relationship between Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Health: Factors that Influence Individuals with or at Risk of CVD. 2019. Available online: https://www.heart.org/-/media/Files/About-Us/Policy-Research/Policy-Positions/Social-Determinants-of-Health/ACEs-Policy-Statement.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2022).

- Vink, R.M.; van Dommelen, P.; van der Pal, S.M.; Eekhout, I.; Pannebakker, F.D.; Velderman, M.K.; Haagmans, M.; Mulder, T.; Dekker, M. Self-reported adverse childhood experiences and quality of life among children in the two last grades of Dutch elementary education. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 95, 104051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Miranda, A.A.; Salemi, J.L.; King, L.M.; Baldwin, J.A.; Berry, E.; Austin, D.A.; Scarborough, K.; Spooner, K.K.; Zoorob, R.J.; Salihu, H.M. Adverse childhood experiences and health-related quality of life in adulthood: Revelations from a community needs assessment. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanlongbutra, A.; Singh, G.K.; Mueller, C.D. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Chronic Disease Risks in Rural Areas of the United States. J. Environ. Public Health 2018, 2018, 7151297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Current Heart Condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||||

| Variables | n | % | n | % | p-Value |

| Age in 3 groups | 0.145 | ||||

| 0–5 | 238 | 28.81 | 19,264 | 28.63 | |

| 6–11 | 265 | 32.08 | 20,613 | 30.63 | |

| 12–17 | 323 | 39.10 | 27,411 | 40.74 | |

| Sex | 0.340 | ||||

| Male | 462 | 55.93 | 34,719 | 51.60 | |

| Female | 364 | 44.07 | 32,569 | 48.40 | |

| Race and Ethnicity | 0.1705 | ||||

| Hispanic | 105 | 12.71 | 8711 | 12.95 | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 568 | 68.77 | 45,264 | 67.27 | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 66 | 7.99 | 4448 | 6.61 | |

| Other/Multi-racial | 87 | 10.53 | 8865 | 13.17 | |

| Country of Birth | 0.251 | ||||

| In-USA | 782 | 95.72 | 64,546 | 96.76 | |

| Out of US | 35 | 4.28 | 2160 | 3.24 | |

| Family Structure | 0.101 | ||||

| Two parents, currently married | 533 | 65.80 | 46,215 | 70.41 | |

| Two parents, not currently married | 58 | 7.16 | 4035 | 6.15 | |

| Single parent | 175 | 21.60 | 12,826 | 19.54 | |

| Grandparent household | 29 | 3.58 | 1942 | 2.96 | |

| Others | 15 | 1.85 | 623 | 0.95 | |

| Highest level of education of any adult in household | 0.003 | ||||

| Less than high school | 12 | 1.45 | 1741 | 2.59 | |

| High School degree or GED | 137 | 16.59 | 8768 | 13.03 | |

| Some college or technical school | 187 | 22.64 | 15,249 | 22.66 | |

| College degree or higher | 490 | 59.32 | 41,530 | 61.72 | |

| Household income as % of federal poverty level | 0.539 | ||||

| 0–99% | 124 | 15.01 | 7945 | 11.81 | |

| 100–199% | 151 | 18.28 | 11,158 | 16.58 | |

| 200–399% | 242 | 29.30 | 20,812 | 30.93 | |

| ≥400% | 309 | 37.41 | 27,373 | 40.68 | |

| Type of health insurance | 0.041 | ||||

| Public | 224 | 27.62 | 13,454 | 20.31 | |

| Private | 516 | 63.63 | 47,096 | 71.08 | |

| Public and Private | 40 | 4.93 | 2385 | 3.60 | |

| Uninsured | 31 | 3.82 | 3323 | 5.02 | |

| Heart Condition | Severity of Heart Condition | Overall Health Status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes % 1.13 | No % 98.87 | p-Value | Mild % 75.38 | Mod/ Sever 24.62% | p-value | Excel % 90.45 | Non-Excel % 9.55 | p-Value | |

| Internal ACEs | |||||||||

| Parent or guardian died | 0.664 | 0.019 | 0.865 | ||||||

| Yes | 2.52 | 2.84 | 3.20 | 0.46 | 2.62 | 2.38 | |||

| No | 97.48 | 97.15 | 96.80 | 99.53 | 97.38 | 97.62 | |||

| Parent or guardian divorced or separated | 0.236 | 0.189 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Yes | 26.27 | 22.76 | 23.45 | 34.97 | 21.55 | 34.15 | |||

| No | 76.8 | 77.24 | 76.55 | 65.03 | 78.45 | 65.85 | |||

| Witnessed domestic violence | 0.050 | 0.227 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 8.59 | 5.20 | 6.91 | 13.72 | 3.52 | 17.05 | |||

| No | 91.4 | 94.80 | 93.09 | 86.28 | 96.48 | 82.95 | |||

| Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drug | <0.01 | 0.740 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Yes | 18.13 | 8.37 | 17.54 | 20.11 | 13.06 | 26.64 | |||

| No | 81.87 | 91.63 | 82.46 | 79.89 | 86.94 | 73.36 | |||

| Hard to cover basics such as food and housing on family’s income | <0.01 | 0.040 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Somewhat often/very often | 31.01 | 13.91 | 25.67 | 47.47 | 19.30 | 51.40 | |||

| Rarely | 68.99 | 86.09 | 74.33 | 52.53 | 80.70 | 48.60 | |||

| Parent or guardian served time in jail | 0.009 | 0.023 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 11.85 | 6.97 | 8.41 | 22.47 | 5.03 | 23.38 | |||

| No | 88.15 | 93.20 | 91.59 | 77.53 | 94.97 | 76.62 | |||

| Lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal or severely depressed | <0.01 | 0.433 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Yes | 17.41 | 8.08 | 15.41 | 23.54 | 9.90 | 31.76 | |||

| No | 82.59 | 91.92 | 84.59 | 76.46 | 90.10 | 68.24 | |||

| External ACEs | |||||||||

| Treated or judged unfairly because due to race/ethnicity | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.009 | ||||||

| Yes | 11.02 | 4.79 | 5.90 | 26.78 | 4.69 | 21.74 | |||

| No | 88.98 | 95.21 | 94.1 | 73.22 | 95.30 | 78.26 | |||

| Victim of/witnessed neighborhood violence | 0.001 | 0.822 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Yes | 7.69 | 3.89 | 7.93 | 7.01 | 5.12 | 12.68 | |||

| No | 92.31 | 96.11 | 92.07 | 92.98 | 94.87 | 87.32 | |||

| Number of ACEs | <0.001 | 0.122 | <0.01 | ||||||

| None | 42.92 | 61.14 | 47.83 | 27.66 | 52.72 | 25.59 | |||

| 1 | 27.36 | 21.47 | 26.37 | 30.50 | 28.38 | 25.95 | |||

| ≥2 | 29.72 | 17.39 | 25.80 | 41.84 | 18.90 | 48.46 | |||

| Heart Conditions a | Severity of Heart Conditions b | Overall Health Status c | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | C.I | p-Value | aOR | C.I | p-Value | aOR | C.I | p-Value | |

| Internal ACEs | |||||||||

| Parent or guardian died | 0.87 | 0.48–1.58 | 0.655 | 0.07 | 0.009–0.62 | 0.017 | 0.32 | 0.06–1.59 | 0.166 |

| Parent or guardian divorced or separated | 1.12 | 0.82–1.54 | 0.459 | 1.55 | 0.71–3.38 | 0.266 | 1.00 | 0.50–1.99 | 0.992 |

| Witnessed domestic violence | 1.54 | 0.87–2.74 | 0.134 | 1.50 | 0.43–5.25 | 0.517 | 2.38 | 0.92–6.19 | 0.074 |

| Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drug | 2.42 | 1.58–3.69 | <0.01 | 1.02 | 0.43–2.43 | 0.955 | 1.93 | 0.94–3.95 | 0.071 |

| Hard to cover basics such as food and housing on family’s income | 3.13 | 1.98–4.95 | <0.01 | 2.05 | 0.72–5.83 | 0.177 | 2.96 | 1.26–6.92 | 0.012 |

| Parent or guardian served time in jail | 1.57 | 0.95–2.61 | 0.077 | 2.47 | 0.76–7.96 | 0.130 | 3.31 | 1.28–8.54 | 0.013 |

| Lived with anyone who was mentally ill, suicidal or severely depressed | 2.26 | 1.35–3.79 | 0.002 | 0.94 | 0.38–2.34 | 0.908 | 2.98 | 1.51–5.85 | 0.001 |

| External ACEs | |||||||||

| Treated or judged unfairly because due to race/ethnicity | 3.13 | 1.28–7.65 | 0.012 | 5.66 | 1.66–19.28 | 0.006 | 2.97 | 0.86–10.27 | 0.085 |

| Victim of/witnessed neighborhood violence | 1.88 | 1.15–3.08 | 0.011 | 0.44 | 0.13–1.46 | 0.183 | 1.74 | 0.55–5.44 | 0.341 |

| Number of ACEs | |||||||||

| 1 | 1.98 | 1.29–3.05 | 0.002 | 2.09 | 0.78–5.62 | 0.141 | 1.05 | 0.40–2.70 | 0.918 |

| ≥2 | 2.75 | 1.82–4.16 | <0.01 | 1.85 | 0.74–4.63 | 0.184 | 2.31 | 1.07–4.96 | 0.031 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adebiyi, E.; Pietri-Toro, J.; Awujoola, A.; Gwynn, L. Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Heart Conditions in Children: Insight from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. Children 2023, 10, 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030486

Adebiyi E, Pietri-Toro J, Awujoola A, Gwynn L. Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Heart Conditions in Children: Insight from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. Children. 2023; 10(3):486. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030486

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdebiyi, Ebenezer, Jariselle Pietri-Toro, Adeola Awujoola, and Lisa Gwynn. 2023. "Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Heart Conditions in Children: Insight from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health" Children 10, no. 3: 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030486

APA StyleAdebiyi, E., Pietri-Toro, J., Awujoola, A., & Gwynn, L. (2023). Association of Adverse Childhood Experiences with Heart Conditions in Children: Insight from the 2019–2020 National Survey of Children’s Health. Children, 10(3), 486. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030486