Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The outcome and effectiveness evaluation of perinatal palliative care compared to regular care provided on:

- ➢

- Pain and/or symptom relief;

- ➢

- Quality of care;

- ➢

- Quality of life of fetuses/infants, parents, family members and involved healthcare providers;

- Detailing which working components are incorporated in such perinatal palliative care programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Registration

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Article Eligibility Criteria

2.3.1. Article Designs

2.3.2. Population

2.3.3. Intervention

2.4. Article Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Data Synthesis

3. Results

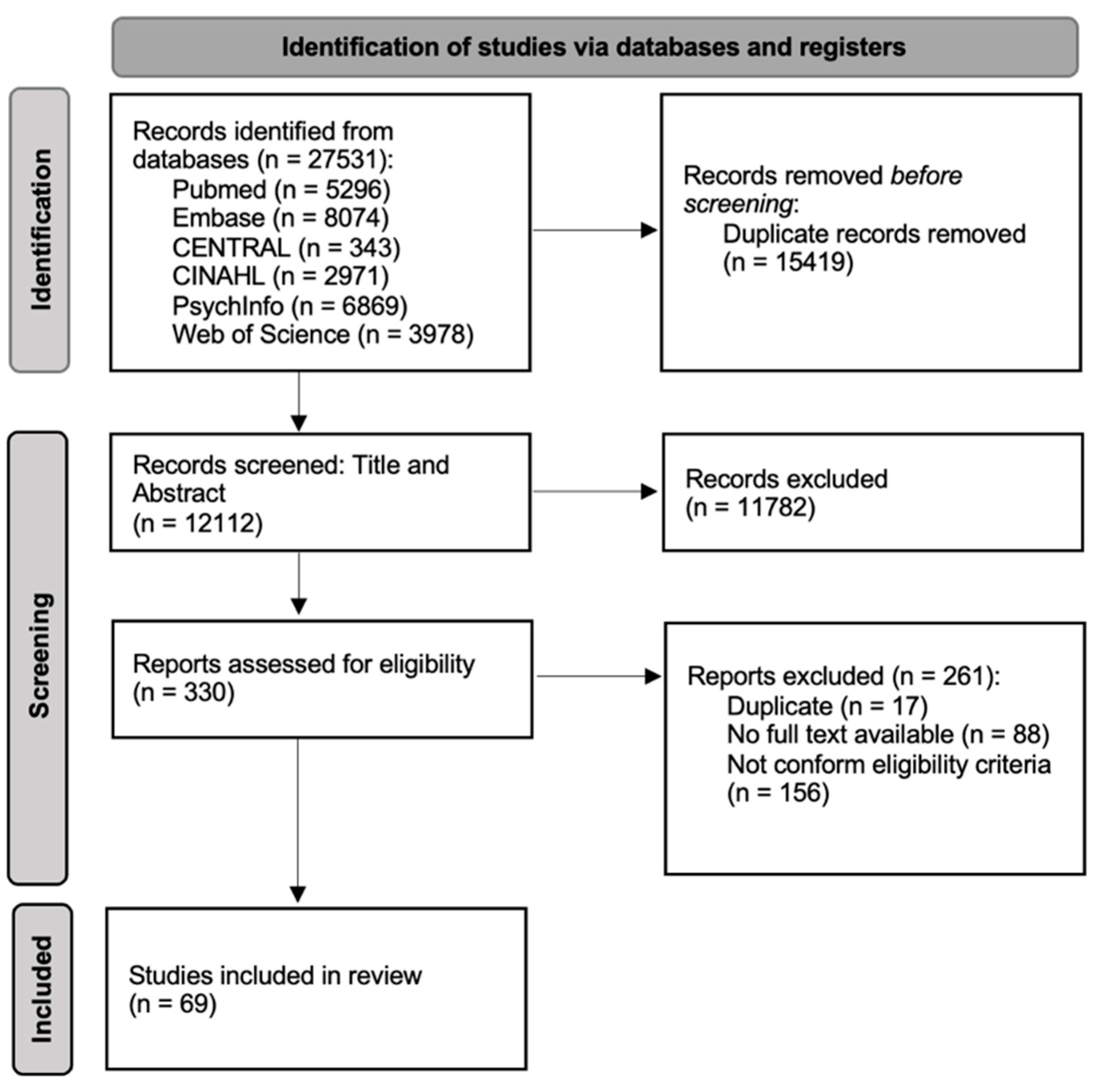

3.1. Article Selection

3.2. Article Characteristics

3.3. Outcomes and Effect Evaluation of Perinatal Palliative Care

3.3.1. Care Coordination

3.3.2. Parents and Family Members

3.3.3. Fetus and/or Neonate

3.3.4. Healthcare Providers

3.4. Working Components of Perinatal Palliative Care

3.4.1. Practical Organization of a Perinatal Palliative Care Team—10 Main Components

- Perinatal palliative care team members: Firstly, members of the core perinatal palliative care team need to be selected. Variation existed among programs included in this review; however, physicians (either an OB-GYN, a neonatologist and/or a pediatrician were most common), nurses and/or midwives, and psychosocial support such as a social worker and/or a psychologist were generally considered part of the core team. Furthermore, a care coordinator was often included to guide family members through the process from diagnosis until death/stillbirth and bereavement, their main goal consisting of being a familiar face and keeping up with scheduled appointments. Additionally, team members could be added when needed for a specific case, including organ specialists, religious and/or spiritual support providers, general practitioners, etc.

- Activation of the perinatal palliative care team: When providing perinatal palliative care, decisions need to be made concerning who is eligible to receive such care and when the perinatal palliative care team will be involved. Eligibility criteria varied from severe prenatal diagnosis to (extremely) premature infants and neonates with serious illness diagnosed after birth. Furthermore, some programs indicated their involvement solely when the pregnancy of a child with a severe prenatal diagnosis would be carried to term, whilst a limited number of programs included care for families opting for a (late) termination of pregnancy. Lastly, programs could be included in care whilst curative treatment was still sought, while others were only called when curative care was deemed futile.

- Providing a place and/or circumstances for palliative care: A maternity ward or neonatal intensive care unit is often not equipped as an ideal environment for families saying goodbye to their child. Providing adequate perinatal palliative care thus often included adjustments to the environment to ensure privacy for the grieving family and peace and quiet from the loud intensive care unit to enjoy limited quality time together. It also means to allow bonding with others, including (grand)parents, siblings, relatives and friends.

- Step-by-step plan: A checklist or protocol was often included in the perinatal palliative care program to direct involvement of the perinatal palliative care team in a structured manner.

- Organization of communication between the care team: A clear and detailed way of documenting is needed to record all conversations and decisions made for a child and/or family. Electronic patient records could be modified or separate shared documents could be made so that information is easily shared with all stakeholders. Additionally, regular meetings with the core perinatal palliative care teams are needed to keep everyone up to date and to ensure continuity of care when transfer from the prenatal to the neonatal team is necessary.

- Teaching of staff members: Perinatal palliative care programs often provided their members, and sometimes even all members of the regular prenatal or neonatal team, with either formal training (including palliative care training, communication training, organ procurement training, etc.) or on-the-job training moments. On-the-job training moments could include, for example, regular mortality and morbidity meetings, palliative care orientation for new staff members or supervision by more experienced team members.

- Collaboration with hospice or palliative home care services: When possible, some perinatal palliative care teams set up a regular collaboration with existing (pediatric) hospice services or palliative home care services, allowing families to take their child home.

- A regular audit of the perinatal palliative care approach: Some perinatal palliative care programs specifically include fixed moments to review or update their care approach according to the newest developments and insights.

- Fundraising for the program: Several programs mentioned the need for fundraising activities to provide perinatal palliative care freely to all families in need.

- Community awareness and involvement: Informing the public on how they can aid families going through perinatal loss can add an additional layer of support.

3.4.2. Care Components of the Perinatal Palliative Care Program—6 Main Components

- Child-directed care: These components include (medical) care provided directly to the child or fetus either before or after death.

- Ensuring comfort of the child (non-medical): A main goal of perinatal palliative care was often to ensure that the child is comfortable by limiting unnecessary and often painful assessments and treatments, providing a stress-free environment with minimal light and/or noise, providing skin-to-skin contact, and co-bedding with multiples.

- Adequate pain/symptom management: Aside from non-medical procedures to ensure comfort, adequate pain and/or symptom management is provided to relieve pain and suffering. Additionally, validated pain and comfort scales can be used to assess pain or suffering in nonverbal neonates so that medication can be adjusted accordingly.

- Food/nutrition provision: Whilst breastfeeding when the child is able is universally considered beneficial during perinatal palliative care, variability consists in whether or not artificial food or nutrition should be provided.

- Other care provided to the child: Perinatal palliative care programs sometimes discuss other care provided to the children in the (neonatal) intensive care unit, such as dressing the child, bathing, and monitoring of vital signs, which can provide comfort to family members or healthcare providers or allow for bonding moments.

- Care of the child after death: Providing perinatal palliative care often included caring for the body after the child passed away. This encompasses bringing the body to a morgue, providing visiting options after death and options to cool and sometimes even rewarm the body.

- Postmortem medical procedures: Death of a fetus and/or neonate brings forward specific medical challenges, such as scheduling an autopsy or performing postmortem tests to confirm a diagnosis, which can be very important for family members in light of future pregnancies. Furthermore, the perinatal palliative care team often prepares for parents wanting to donate their child’s organs.

- Family-directed care: Perinatal palliative care was often discussed to be directed mainly towards family members, such as parents, siblings, grandparents and other close relatives/friends. The following care components were mentioned:

- Family-centered care: Adept care was tailored to the values, hopes, needs and cultural background of the family (within reasonable limits). Care was customized for individual family members as much as possible, including, for example, providing a translator or speaking to religious representatives of the family. Care can be tailored to the parents and family as a whole or even separately for individual family members when needed.

- Promote family bonding and parenting: Perinatal palliative care includes promoting family bonding and making memories, both during life and after death of the infant. This means supporting families to make the most out of the little time they have with their infant, including taking part in caring for their child. However, some programs mention having respect for the families’ wishes not to bond.

- Family-centered psychosocial support: Programs providing perinatal palliative care often include a strong and constantly available psychosocial support system directed towards the family, including, but not limited to, social services, social workers, psychologists, chaplains and references to support groups. Some programs pay specific attention to siblings or parents other than the mother or to providing support during a new pregnancy.

- Bereavement support and follow-up appointments with physicians, nurses, midwives, psychosocial workers or other members of the (core) team are mentioned as another essential component of family-centered psychosocial support.

- Religious and/or spiritual support can be provided if parents so wish, allowing for specific rituals and ceremonies tailored to their specific needs.

- Practical support: Families might need more practical forms of support such as aid in funeral planning, registering the birth and the death of the child and informing other organizations on the death of their child, which is also included in several perinatal palliative care programs.

- Healthcare provider directed care: A third recipient of perinatal palliative care support mentioned are the healthcare providers responsible for caring for the fetus/infant and the family. The following components are included:

- Support for healthcare providers: Some perinatal palliative care programs discuss formal or informal means of support for healthcare providers, ranging from psychological support during working hours to being able to ask questions to more experienced peers and colleagues.

- Debriefings after death: Formal debriefings of the multidisciplinary staff members after the death of a child can provide time to reflect on what happened and what could be improved. Additionally, possible conflicts, problems and issues can be addressed.

- Relieve healthcare providers of other tasks when caring for an infant in their final moments: Fixed staff members, such as nurses or physicians, are indicated to be available at all times during the dying process. Other tasks can be taken care of by colleagues during this time spent in close contact with the family.

- Advance care planning: Aside from care directed to a specific recipient of perinatal palliative care, a large care component focusses on advance care planning when the medical situation allows it. This means that time is available to make decisions beforehand instead of during crisis situations. Different scenarios of care are discussed with healthcare providers and parents/family members so that a future treatment plan can be set up. We identified the following subcomponents:

- Care plan during pregnancy and/or life of the child: When a prenatal diagnosis is made, the prenatal care plan can be discussed beforehand, including decisions on whether or not all regular examinations are still needed or wanted during pregnancy and how maternal health, both psychosocial and medical, will be assessed. An important prenatal decision in case of severe fetal diagnoses is whether curative treatment, non-aggressive obstetric management, neonatal palliative care or (late) termination of pregnancy with or without feticide is preferred. Furthermore, a birth plan can be made, including deciding on the mode and time of delivery, who should be present, how maternal comfort will be assured and whether fetal monitoring is required. Lastly, a neonatal care plan can be made when survival past birth is possible or when the severe diagnosis is made post birth. The neonatal care plan includes discussing curative and palliative care (both can occur simultaneously); discussing possible courses of action depending on the medical situation of the child, such as resuscitation, treatments and possibly limiting care, and confirming the prenatal diagnosis neonatally.

- Death plan: When death or stillbirth is a possibility, healthcare providers can provide parents/family members with possible scenarios of what could happen. These conversations include inquiring about preferences regarding religious ceremonies, washing and clothing the infant, taking pictures and making memories. Additionally, a bereavement care plan can be set up, where healthcare providers and parents discuss when follow-ups will take place and what support parents anticipate needing.

- Regular revisions of the care plan: Preferences of the parents (and the healthcare providers) can change rapidly when new information becomes available or when individuals change their minds. The care plan can thus be reassessed regularly and is considered flexible.

- Components regarding the decision-making process with parents/family members: When a severe diagnosis is made before or after birth, decisions can often be made beforehand. Here, advance care planning can take place, yet this is not always the case. Irrespective of when these decisions are made, key care components in perinatal palliative care focus specifically on which information is shared, how this information is shared, who makes decisions and how conflicts are handled.

- Which information is shared: Information regarding diagnosis and prognosis is shared openly and honestly, not only with parents but with the entire medical team including nurses, psychologists and social workers. Prognostic uncertainty can be addressed, and parents need to be prepared for possible disease trajectories. Healthcare providers sometimes raise topics for discussion in family meetings when parents leave them open, such as discussing what they can expect during the dying phase. All possible treatment options and their consequences are provided, including curative options, limiting treatment, providing comfort care or termination of the pregnancy.

- The manner of sharing information: Regular, planned and formal consultations with parents are to be scheduled. During these consultations, parents have the ability to see all members of the care team so that they are adequately informed. A care coordinator can be useful as a set point of contact for parents so that someone is (almost) always available for questions. The provided information is presented in an understandable way to parents and is thus often tailored to their knowledge level, norms and (cultural) values. Translators are involved when needed, and information is repeated multiple times. Comprehension is often assessed. Information is provided in a compassionate manner, respecting norms, values and wishes. If conflicts arise concerning these norms, values and wishes, conflict resolution might be needed (see further).

- Shared decision making: Inquire about the role parents would like to play in decision making. Shared decision making is recommended in most programs; however, some parents indicate not wanting to be involved. Healthcare providers support patient (and in this case parent) advocacy, empowering parents to participate in decision making.

- Conflict resolution: Conflicts between healthcare providers and parents can arise concerning, for example, treatment options, limiting care, involvement in decision making, and openly sharing information. An ethics consult or (cultural) mediation is sometimes provided, and parents are provided options to seek a second opinion. Additionally, for conflicts arising between healthcare providers of the team, perinatal palliative care programs include the possibility to step down from a case, providing mediators and accurately debriefing conflicts afterwards.

- Care of externals: Four perinatal palliative care programs briefly mentioned support for externals. This component differs significantly from the previous care components, which are directed towards the child/fetus or actors in direct contact with a specific child/fetus. This component includes:

- Care for other families at the ward: In the neonatal ward, families often share rooms. The death of a child in the ward can take away hope for their own child, which was in this case adequately addressed to other families.

4. Discussion

4.1. Considerations

4.2. General Discussion

- Firstly, within one palliative care program, the sole recipients of care are most often live-born infants or families where a severe fetal diagnosis was made before birth where the pregnancy was continued. This could lead to fragmented care as providing care for perinatal loss is similar before and after birth [5]. Additionally, 16% of reported programs included care provision in case of termination of pregnancy. Future research should investigate whether people eventually choosing to terminate the pregnancy could also benefit from receiving perinatal palliative care so that all perinatal palliative care needs are met.

- Secondly, inconsistencies occur in the amount and the duration of bereavement support, ranging from follow-up phone calls [46], home visits or mail [48]; providing follow-up appointments with physicians [34] or conversations with nurses [40], psychologists, chaplains [59] or others and lasting for an undetermined [51] or fixed [60] amount of time, even years after the loss of their child [70]. This raises questions on what constitutes bereavement care and how long perinatal palliative care programs should offer this service, which is currently unclear and needs further examination.

- Thirdly, when providing support, the focus was most often on the mother. Only two publications explicitly mentioned support for the father or significant other [74,76], who also has the tendency to focus on the mother and her wellbeing [76]. Future perinatal palliative care programs should be aware of this and aim to provide support to both parents when applicable, tailored to their individual needs.

- There were various ways of making sure neonates are being kept comfortable. This was performed by both non-medical treatment of the infant, such as limiting unnecessary and often painful assessments [72], skin-to-skin contact [38] and reducing noise and lights [11], as well as by medical treatment providing adequate pain and symptom relief.

- In all included publications, opposing views on which care should be provided was rare; however, discussion arises on whether or not artificial nutrition and hydration should be continued until death. While some programs anticipate providing parenteral or oral feeding to keep the child comfortable [55], others focused on stopping artificial nutrition and hydration during the dying process [58]. In such situations, the comfort of the child should come first; therefore, when artificial nutrition and hydration do not increase comfort, we would consider it pointless and possibly even burdensome for the child. However, breastfeeding was always considered beneficial when the child is able to [52].

- Lastly, care for the infant after he or she passed away seems to be exclusive to the perinatal population, including, for example, cooling and even rewarming the body [65] or procuring organs for organ donation specific to the neonatal population [11]. We feel that specialized training or information sessions for healthcare providers on these topics could be beneficial.

- Only 22% of included programs discuss professional support for healthcare providers being tasked with providing perinatal palliative care, for example by offering consults with a psychologist, ethics consultant, psychiatry staff or social workers. Whether this lack of support is due to it being deemed unnecessary, or due to it being classed as subordinate to support for the family is unclear.

- Additionally, debriefings, recommended by 19% of discussed programs, could serve as a tool to reflect on what happened and address possible conflicts, problems and issues. However, no details are given on when and how often these debriefings should take place, who should participate, and what should be discussed.

- Lastly, while multiple programs focused on providing aid to family members during the advance care planning and decision-making process, details on supporting healthcare providers during this process were limited to recommending specialized training. We therefore feel that support for healthcare providers in perinatal palliative care could be expanded in the development of future programs and initiatives. (For more references on components raised in this discussion, see Table 5).

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rüegger, C.; Hegglin, M.; Adams, M.; Bucher, H.U. Population Based Trends in Mortality, Morbidity and Treatment for Very Preterm- and Very Low Birth Weight Infants over 12 Years. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlieger, R.; Martens, E.; Goemaes, R.; Cammu, H. Perinatale Activiteiten in Vlaanderen 2017; VZW Studiecentrum voor Perinatale Epidemiologie (SPE): Brussel, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, W.D. Committee on Fetus and Newborn Standard Terminology for Fetal, Infant, and Perinatal Deaths. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20160551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denney-koelsch, E.; Black, B.P.; Côté-Arsenault, D.; Wool, C.; Sujeong, K.; Kavanaugh, K. A Survey of Perinatal Palliative Care Programs in the United States: Structure, Processes, and Outcomes. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrecht, L.; Beernaert, K.; Roets, E.; Chambaere, K.; Cools, F.; Goossens, L.; Naulaers, G.; De Catte, L.; Cohen, J.; Deliens, L.; et al. A Post-Mortem Population Survey on Foetal-Infantile End-of-Life Decisions: A Research Protocol. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Wool, C. State of the Science on Perinatal Palliative Care. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wool, C.; Côté-Arsenault, D.; Perry Black, B.; Denney-Koelsch, E.; Kim, S.; Kavanaugh, K. Provision of Services in Perinatal Palliative Care: A Multicenter Survey in the United States. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidgwick, P.; Harrop, E.; Kelly, B.; Todorovic, A.; Wilkinson, D. Fifteen-Minute Consultation: Perinatal Palliative Care. Arch. Dis. Child. Educ. Pract. 2017, 102, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, A.; Martín-ancel, A.; Ortigoza-escobar, D.; Escribano, J.; Argemi, J. The Model of Palliative Care in the Perinatal Setting: A Review of the Literature the Model of Palliative Care in the Perinatal Setting: A Review of the Literature. BMC Pediatr. 2012, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catlin, A.; Carter, B. Creation of a Neonatal End-of-Life Palliative Care Protocol. J. Perinatol. 2002, 22, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, T.R.; Bernardes, L.S.; Benute, G.R.G.; Gibeli, M.A.B.C.; do Nascimento, N.B.; Barbosa, T.V.A.; Krebs, V.L.J.; Francisco, R.P.V. When One Knows a Fetus Is Expected to Die: Palliative Care in the Context of Prenatal Diagnosis of Fetal Malformations. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 1020–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parravicini, E. Neonatal Palliative Care. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2017, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samsel, C.; Lechner, B.E. End-of-Life Care in a Regional Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit after Implementation of a Palliative Care Initiative. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younge, N.; Smith, P.B.; Goldberg, R.N.; Brandon, D.H.; Simmons, C.; Cotten, C.M.; Bidegain, M. Impact of a Palliative Care Program on End-of-Life Care in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcmahon, D.L.; Twomey, M.; O’Reilly, M.; Devins, M. Referrals to a Perinatal Specialist Palliative Care Consult Service in Ireland, 2012–2015. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2018, 103, F573–F576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, B.S. Pediatric Palliative Care in Infants and Neonates. Children 2018, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parravicini, E.; Foe, G.; Steinwurtzl, R.; Byrne, M. Parental Assessment of Comfort in Newborns Affected by Life-Limiting Conditions Treated by a Standardized Neonatal Comfort Care Program. J. Perinatol. 2018, 38, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petteys, A.R.; Goebel, J.R.; Wallace, J.D.; Singh-Carlson, S. Palliative Care in Neonatal Intensive Care, Effects on Parent Stress and Satisfaction: A Feasibility Study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2015, 32, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marc-aurele, K.L.; Nelesen, R. A Five-Year Review of Referrals for Perinatal Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2013, 16, 1232–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosello, B.; Dany, L.; Gire, C.; Béthémieux, P.; Vriet-Ndour, M.-E.; Le Coz, P.; D’Ercole, C.; Siméoni, U.; Einaudi, M. Perceptions of Lethal Fetal Abnormality among Perinatal Professionals and the Challenges of Neonatal Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 924–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, B.; Hoeldtke, N.; Hinson, R.; Judge, K. Perinatal Hospice: Should All Centers Have This Service? Neonatal Netw. 1997, 16, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Limbo, R.; Wool, C. Perinatal Palliative Care. JOGNN—J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2016, 45, 611–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beller, E.M.; Glasziou, P.P.; Altman, D.G.; Hopewell, S.; Bastian, H.; Chalmers, I.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Lasserson, T.; Tovey, D. PRISMA for Abstracts: Reporting Systematic Reviews in Journal and Conference Abstracts. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolognani, M.; Morelli, P.D.; Scolari, I.; Dolci, C.; Fiorito, V.; Uez, F.; Graziani, S.; Stefani, B.; Zeni, F.; Gobber, G.; et al. Development of a Perinatal Palliative Care Model at a Level II Perinatal Center Supported by a Pediatric Palliative Care Network. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 574397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, K.; Steinwurtzl, R.; Brumarie, L.; Schechter, S.; Parravicini, E. Early Palliative Care Reduces Stress in Parents of Neonates with Congenital Heart Disease: Validation of the “Baby, Attachment, Comfort Interventions”. J. Perinatol. 2019, 39, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalowska, A.; Krzeszowiak, J.; Stembalska, A.; Szmyd, K.; Zimmer, M.; Jagielska, G.; Raś, M.; Pasławska, A.; Szafrańska, A.; Paluszyńska, D.; et al. Perinatal Palliative Care Provided in the Maternity and Neonatal Ward in Cooperation with a Hospice for Children—Own Experience. J. Mother Child 2019, 23, 253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Loyet, M.; McLean, A.; Graham, K.; Antoine, C.; Fossick, K. The Fetal Care Team: Care for Pregnant Women Carrying a Fetus with a Serious Diagnosis. Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2016, 41, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalen, F.; Cavicchiolo, M.E.; Lago, P.; Salvadori, S.; Benini, F. Perinatal Palliative Care: Is Palliative Care Really Available to Everyone? Ann. Palliat. Med. 2018, 7, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, S.E. Raising the Bar: Development of a Perinatal Bereavement Programme. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2019, 25, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Liang, Y.F.; Tinnion, R. Neonatal Palliative Care: A Practical Checklist Approach. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2020, 10, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewani, K.G.; Jayagobi, P.A.; Chandran, S.; Anand, A.J.; Thia, E.W.; Bhatia, A.; Bujal, R.; Khoo, P.C.; Quek, B.H.; Tagore, S.; et al. Perinatal Palliative Care Service: Developing a Comprehensive Care Package for Vulnerable Babies with Life Limiting Fetal Conditions. Journal of Palliative Care, 08258597211046735. J. Palliat. Care 2021, 37, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akyempon, A.N.; Aladangady, N. Neonatal and Perinatal Palliative Care Pathway: A Tertiary Neonatal Unit Approach. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e000820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.; Dutcher, J.; Snyders, M. Embrace: Addressing Anticipatory Grief and Bereavement in the Perinatal Population: A Palliative Care Case Study. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2011, 25, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bétrémieux, P.; Gold, F.; Parat, S.; Farnoux, C.; Rajguru, M.; Boithias, C.; Mahieu-Caputo, D.; Jouannic, J.M.; Hubert, P.; Simeoni, U. Implementing Palliative Care for Newborns in Various Care Settings. Part 3 of “Palliative Care in the Neonatal Period”. Arch. Pédiatr. 2010, 17, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breeze, A.; Lees, C.; Kumar, A.; Missfelder-Lobos, H.; Murdoch, E. Palliative Care for Prenatally Diagnosed Lethal Fetal Abnormality. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007, 92, F56–F58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabareta, A.S.; Charlota, F.; Le Bouara, G.; Poulaina, P.; Bétremieux, P. Very Preterm Births (22-26 WG): From the Decision to the Implement of Palliative Care in the Delivery Room. Experience of Rennes University Hospital (France). J. Gynécol. Obstêt. Biol. Reprod. 2012, 41, 460–467. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, B.S.; Bhatia, J. Comfort/Palliative Care Guidelines for Neonatal Practice: Development and Implementation in an Academic Medical Center. J. Perinatol. 2001, 21, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, C.; Spicer, S.; Curiel, K. Case 1: A Primary Care Provider Enhances Family Support in Perinatal Palliative Care. Paediatr. Child Health 2015, 20, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, B. A Case of Anencephaly: Integrated Palliative Care. N. Z. Coll. Midwives J. 2013, 48, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J.C.M.; Moldenhauer, J.S.; Jones, T.R.; Shaughnessy, E.A.; Zarrin, H.E.; Coursey, A.L.; Munson, D.A. A Proposed Model for Perinatal Palliative Care. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2017, 46, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway-Orgel, M.; Edlund, B.J. Challenges in Change: The Perils and Pitfalls of Implementing a Palliative Care Program in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2015, 17, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czynski, A.J.; Souza, M.; Lechner, B.E. The Mother Baby Comfort Care Pathway: The Development of a Rooming-In–Based Perinatal Palliative Care Program. Adv. Neonatal Care 2022, 22, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahò, M. An Exploration of the Emotive Experiences and the Representations of Female Care Providers Working in a Perinatal Hospice. A Pilot Qualitative Study. Clin. Neuropsychiatry 2021, 18, 55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Burlet, A.S. A Nurse’s View on Accompanying Babies through End-of-Life Care at a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Méd. Palliat. 2016, 15, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisle-Porter, M.; Podruchny, A.M. The Dying Neonate: Family-Centered End-of-Life Care. Neonatal Netw. 2009, 28, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelder, S.; Davies, K.; Zeilinger, T.; Rutledge, D. A Model Program for Perinatal Palliative Services. Adv. Neonatal Care 2012, 12, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, N.K.; Hessler, K.L. Prenatal Birth Planning for Families of the Imperiled Newborn. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2013, 42, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falke, M.; Rubarth, L.B. Implementation of a Perinatal Hospice Program. Adv. Neonatal Care 2020, 20, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, T.C.; Bloom, A.M. When Death Precedes Birth: Experience of a Palliative Care Team on a Labor and Delivery Unit. J. Palliat. Med. 2012, 15, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, G.; Brooks, A. Implementing a Palliative Care Program in a Newborn Intensive Care Unit. Adv. Neonatal Care 2006, 6, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garten, L.; von der Hude, K.; Rösner, B.; Klapp, C.; Bührer, C. Individual Neonatal End-of-Life Care and Family-Centred Bereavement Support. Z. Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2013, 217, 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- Garten, L.; Globisch, M.; von der Hude, K.; Jäkel, K.; Knochel, K.; Krones, T.; Nicin, T.; Offermann, F.; Schindler, M.; Schneider, U.; et al. Palliative Care and Grief Counseling in Peri- and Neonatology: Recommendations From the German PaluTiN Group. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, D.P.G.; Areias, M.H.F.G.P.; de Almeida Ramalho, C.M.; Rodrigues, M.M. Perinatal Palliative Care Following Prenatal Diagnosis of Severe Fetal Anomaly: A New Family-Centered Approach in a Level III Portuguese Hospital. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Individ. Med. 2019, 8, e080102. [Google Scholar]

- Haxel, C.; Glickstein, J.; Parravicini, E. Neonatal Palliative Care for Complicated Cardiac Anomalies: A 10-Year Experience of an Interdisciplinary Program at a Large Tertiary Cardiac Center. J. Pediatr. 2019, 214, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeldtke, N.J.; Calhoun, B.C. Perinatal Hospice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 185, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.; Vasudevan, C. Palliative Care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 30, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.G.; Hauck, C.B.; Mandel, D.A. Perinatal Palliative Care: The Nursing Perspective. Nurs. Womens Health 2010, 14, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenner, C.; Press, J.; Ryan, D. Recommendations for Palliative and Bereavement Care in the NICU: A Family-Centered Integrative Approach. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, S19–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobler, K.; Limbo, R. Making a Case: Creating a Perinatal Palliative Care Service Using a Perinatal Bereavement Program Model. J. Perinat. Neonatal Nurs. 2011, 25, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz, A.; Kozinska, J.; Kozinski, K.; Dryja, U. Prenatal Diagnosis of a Lethal Defect: What next? History of First Family in Perinatal Hospice. Palliat. Support. Care 2021, 20, 906–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuthner, S.R. Palliative Care of the Infant with Lethal Anomalies. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 51, 747–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuthner, S.R. Fetal Palliative Care. Clin. Perinatol. 2004, 31, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuthner, S.; Jones, E.L. Fetal Concerns Program: A Model for Perinatal Palliative Care. Am. J. Matern. Nurs. 2007, 32, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, C.; Corvaglia, L.; Simonazzi, G.; Bisulli, M.; Paolini, L.; Faldella, G. “Percorso Giacomo”: An Italian Innovative Service of Perinatal Palliative Care. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 589559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longmore, M. Neonatal Nursing: Palliative Care Guidelines. Kai Tiaki Nurs. N. Z. 2016, 22, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Ancel, A.; Pérez-Muñuzuri, A.; González-Pacheco, N.; Boix, H.; Fernández, M.G.E.; Sánchez-Redondo, M.D.; Cernada, M.; Couce, M.L.; en representación del Comité de Estándares; Sociedad Española de Neonatología. Perinatal Palliative Care. An. Pediatr. (Engl. Ed.) 2022, 96, 60.e1–60.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.S.; Cummings, J.J.; Macauley, R.; Ralston, S.J. Perinatal Palliative Care. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 134, e84–e89. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B.; Sprague, R.; Harmon, C.M.; Davis, S. Walk with Me: A Bridge Program for Assisting Families Expecting Babies with Fetal Anomalies and/or a Terminal Diagnosis. Neonatal Netw. 2020, 39, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munson, D.; Leuthner, S.R. Palliative Care for the Family Carrying a Fetus with a Life-Limiting Diagnosis. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 54, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association of Neonatal Nurses board of directors Palliative Care of Newborns and Infants. Position Statement# 3051. Adv. Neonatal Care Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Neonatal Nurses 2010, 10, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte-Buchholtz, S.; Garten, L. Perinatal Palliative Care. Care of Neonates with Life-Limiting Diseases and Their Families. Mon. Kinderheilkd. 2018, 166, 1127–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paize, F. Multidisciplinary Antenatal and Perinatal Palliative Care. Infant 2019, 15, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ramer-Chrastek, J.; Thygeson, M.V. A Perinatal Hospice for an Unborn Child with a Life-Limiting Condition. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2005, 11, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roush, A.; Sullivan, P.; Cooper, R.; McBride, J.W. Perinatal Hospice. Newborn Infant Nurs. Rev. 2007, 7, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalen, F.; Cavicchiolo, M.E.; Lago, P.; Salvadori, S.; Benini, F. Perinatal Palliative Care: A Dedicated Care Pathway. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2021, 11, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusalen, F. Perinatal Palliative Care: A New Challenging Field. J. Palliat. Med. 2020, 23, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, A.; Bernhard, H.; Fahlberg, B. Best Practices for Perinatal Palliative Care. Nursing2020 2015, 45, 14–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, M.; Shaw, V.; Savani, R. Comfort Care of Neonates at the End of Life. Neonatal Netw. 2004, 23, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibeau, S.; Naquin, L. NICU Perspectives on Palliative Care. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2012, 43, 342–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.H.; Ellis, K.; Linebarger, J. Outcomes Following Perinatal Palliative Care Consultation: A Retrospective Review. J. Perinatol. 2021, 41, 2196–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthaya, S.; Mancini, A.; Beardsley, C.; Wood, D.; Ranmal, R.; Modi, N. Managing Palliation in the Neonatal Unit. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014, 99, F349–F352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wool, C.; Parravicini, E. The Neonatal Comfort Care Program: Origin and Growth over 10 Years. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 588432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, T.R.; Kuebelbeck, A. Close to Home: Perinatal Palliative Care in a Community Hospital. Adv. Neonatal Care 2020, 20, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Block | Mesh | Text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Fetus, neonate, infant | “infant, newborn”[MESH] “Fetus”[Mesh:NoExp] | infant* [Title/Abstract] OR newborn* [Title/Abstract] OR neonat* [Title/Abstract] OR newly born [Title/Abstract] OR newly-born [Title/Abstract] OR new-born* [Title/Abstract] Foetus [Title/Abstract] OR Fetus [Title/Abstract] OR Foetal [Title/Abstract] OR Fetal [Title/Abstract] |

| Death of fetus, neonate, infant | “Infant Mortality”[Mesh] OR “Infant Death”[Mesh:NoExp] “Fetal Death”[Mesh] OR “Fetal Mortality”[Mesh] “Perinatal Mortality”[Mesh] OR “Perinatal Death”[Mesh] | (neonatal[tiab] OR perinatal[tiab] OR fetal[tiab] OR foetal[tiab] OR infant[tiab]) AND (death[tiab] OR mortality[tiab] OR demise[tiab] OR loss[tiab]) (Terminat*[Title/Abstract] AND pregnanc*[Title/Abstract]) | |

| Palliative care | “Hospice and Palliative Care Nursing”[Mesh] OR “Palliative Medicine”[Mesh] OR “Palliative Care”[Mesh] OR “Terminal Care”[Mesh] | (palliative[tiab] OR end-of-life[tiab] OR end of life[tiab] OR EOL[tiab] OR comfort[tiab] OR hospice[tiab] OR terminal[tiab]) AND (care[tiab] OR nursing[tiab] OR medicine[tiab]) palliation[tiab] | |

| Perinatal palliative care | perinatal palliative care [Title/Abstract] OR perinatal hospice [Title/Abstract] | ||

| Not animals | NOT (“Animals”[Mesh] NOT “Humans”[Mesh]) |

| Perinatal palliative care: For the purpose of this study, perinatal palliative care will be defined as a multi-component provision of care for fetuses or neonates with a serious illness in the perinatal period (22 weeks of gestation–28 days after birth) and their parents, families and involved healthcare providers, aimed to relieve pain and control symptoms and to improve the quality of care for, and well-being of, fetuses and infants, their families and involved healthcare providers. It is holistic, family-centered, comprehensive, and multidimensional, so that it addresses not only the physical aspect, but also the psychological, social and spiritual dimensions. A serious illness: A serious illness is defined as either a lethal diagnosis in the prenatal or neonatal period, or a diagnosis for which there is little or no prospect of long-term survival without severe morbidity or extremely poor quality of life, and for which there is no cure. We will not define a limited group of diseases for which palliative care is needed to maximize the sensitivity of our search. |

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Targeted Population | Aims/Research Questions | Outcomes and Effect Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bolognani et al. [26] | Italy | Retrospective chart review | Perinatal | To describe the model build up to take care of fetuses and newborns eligible for perinatal palliative care | Facilitated decision making and consensus building, improvement of therapeutic alliance, better flow of information. |

| Callahan et al. [27] | US | Prospective cohort study of parents of neonates with congenital heart disease | Neonatal | To test the hypothesis that an innovative method of early palliative care reduces psychological distress in parents of neonates with congenital heart disease | The study demonstrated that early PC reduced parental stress. Parental depression and anxiety did not decrease with the intervention. |

| Jalowska et al. [28] | Poland | Retrospective chart review | Perinatal | To demonstrate the role of perinatal palliative care in case of severe developmental disorder in the fetus with a potentially lethal prognosis | All mothers in the perinatal hospice program wanted to see and hug their child. All families wanted to participate in memory making and many of them expressed the importance of these memories to the team. |

| Loyet et al. [29] | US | Survey after start of a fetal care team | Perinatal | Improvement in quality of care for women carrying a fetus with a suspected or known fetal anomaly | Patients receiving fetal perinatal palliative care were highly satisfied and felt that support was valuable. Enhanced patients’ feelings of their knowledge of the condition or diagnosis of their fetus. |

| Parravicini et al. [18] | US | Prospective mixed method self-report survey | Neonatal | Assess the perception of parents concerning the state of comfort maintained in their infants affected by life-limiting conditions when treated by the neonatal comfort care program | Parents felt that their baby was comfortable and treated with respect, care and compassion by professionals. The environment was perceived as mostly peaceful, private and non-invasive. |

| Petteys et al. [19] | US | Prospective cohort study | Neonatal | Examine the effects of palliative care on NICU parent stress and satisfaction | PC services did not increase parent stress levels and may decrease stress in parents of the frailest, sickest infants. All PC parents were extremely satisfied with care, versus only 50% of normal care parents. |

| Rusalen et al. 2018 [30] | Italy | Not reported | Perinatal | To evaluate the efficacy and efficiency of their perinatal palliative care protocol | Prenatal consultations by neonatologists increased. The number of newborns who died in the NICU was reduced by 30%. The number of eligible newborns who actually received perinatal palliative care, was still limited. |

| Samsel et al. [14] | US | Retrospective and prospective chart review | Neonatal | Evaluating the impact of the implementation of a palliative care intervention within the NICU on outcomes of dying infants | Redirection of care increased. During the final 48 h of life, palliative medication was administered more often. Contact with social work and/or chaplaincy did not increase significantly. |

| Steen, S.E. [31] | US | Survey | Perinatal | To detail the specifics of a perinatal bereavement program development, and to evaluate feasibility | 70% of families not only found value in having a plan, but also felt that the staff followed the proposed plan. 85% found follow-up phone call helpful, 70% found written support material helpful. Staff has increased confidence in caring for bereaved families owing to the education, support and mentoring they have received. |

| Taylor et al. [32] | US | Case audits on the implementation of checklists of care provided | Neonatal | To examine the quality of locally delivered neonatal palliative care before and after a regional guidance implementation | Checklist of care led to more patients being identified antenatally with life-limiting diagnoses, and timely planning for anticipated care. Improvements of documentation in domains of comfort care, monitoring, fluids and nutrition, completion of diagnostics, treatment ceiling decisions, resuscitation status and discussion with parents. Psychological support was rarely offered, most likely because of a lack of access. No significant difference in pain alleviation. |

| Tewani et al. [33] | Singapore | Chart review after program development | Perinatal | To develop a service providing individually tailored holistic care during pregnancy, birth, postnatal and bereavement period | Care plans including resuscitation and other decisions were made before birth for 63% of cases. Of these, 92% of parents opted for no active resuscitation. 44% demised during the hospital stay. Of those discharged home, 24% are still being supported by the community palliative team. |

| Younge et al. [15] | US | Retrospective study | Neonatal | To evaluate the impact of Neonatal palliative care program on end-of-life care in the NICU | Mortality, postnatal age at death, withdrawal of life-support, incidence of a DNR, amount of morphine administered in the last 24 h, and number of infants receiving neuromuscular blockers did not differ. A greater proportion of infants received benzodiazepines in the final days, the number of meetings to discuss end-of-life care was higher, time between first end-of-life meeting and withdrawal of life-support was longer. |

| Reference | Country | Study Design | Targeted Population | Aims/Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akyempon et al. [34] | UK | Guideline based on recommendations and review of literature | Perinatal | Development neonatal and perinatal palliative care pathway |

| Bennett et al. [35] | US | Case study | Perinatal | Example of a perinatal palliative care interdisciplinary approach |

| Bétrémieux et al. [36] | France | Expert opinion on application of a new palliative care law | Perinatal | Application of a new palliative care law in medical practice |

| Breeze et al. [37] | UK | Case descriptions and comparisons | Prenatal | Examples of pregnancy termination or perinatal palliative care approach in case of lethal fetal abnormality |

| Cabareta et al. [38] | France | Retrospective chart review | Neonatal | Study postnatal management decisions after new neonatal palliative care protocol |

| Carter et al. [39] | US | Delphi method, development of a comfort care guideline using naturalistic inquiry | Neonatal | Development of a neonatal comfort care guideline |

| Catlin et al. [11] | US | Delphi method, build a consensus document on palliative care | Neonatal | Create a protocol for neonatal palliative care |

| Chamberlain et al. [40] | US | Case description | Perinatal | Case description of a perinatal assessment team |

| Chapman, B. [41] | New Zealand | Case study | Perinatal | Describe an approach integrating primary, secondary and community services to perinatal palliative care |

| Cole, J. [42] | US | Program description and case study | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Conway-Orgel et al. [43] | US | Guideline development | Neonatal | Development of an algorithm and program for neonatal palliative care. |

| Czynski et al. [44] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Dahò, M. [45] | US | Semi-structured interviews | Perinatal | Study experiences of the providers working in a Perinatal Hospice program |

| De Burlet, A. S. [46] | Belgium | Program description | Neonatal | Describe a neonatal palliative care protocol |

| De Lisle-Porter et al. [47] | US | Guideline description | Neonatal | Describe an end-of-life care guideline for neonates |

| Denney-Koelsch et al. [4] | US | Survey | Perinatal | Survey of structure and process of perinatal palliative care programs |

| Engelder et al. [48] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a Perinatal Comfort Care program |

| English et al. [49] | US | Program description | Prenatal | Describe a prenatal palliative care program |

| Falke et al. [50] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe the implementation of a perinatal hospice program |

| Friedman et al. [51] | US | Case study | Perinatal | Case description of a palliative care team |

| Gale et al. [52] | US | Program description | Neonatal | Description of a neonatal palliative care program |

| Garten et al. 2013 [53] | Germany | Program description | Neonatal | Recommendations for a basic neonatal palliative care concept |

| Garten et al. 2020 [54] | Germany | Program recommendations | Perinatal | Provide practical guidance in perinatal palliative care |

| Guimaraes et al. [55] | Portugal | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Haxel et al. [56] | US | Retrospective descriptive consecutive case series | Neonatal | Describe outcomes of fetuses and neonates with severe or complicated congenital heart disease treated with neonatal palliative care |

| Hoeldtke et al. [57] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Jackson et al. [58] | UK | Guideline description | Perinatal | Provide guidelines for perinatal palliative care |

| Kauffman et al. [59] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program, including the nursing perspective. |

| Kenner et al. [60] | US | Program recommendations | Perinatal | Provide recommendations for the provision of family-centered perinatal palliative care |

| Kobler et al. [61] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care service in an institution that already has a perinatal bereavement program |

| Korzeniewska-Eksterowicz et al. [62] | Poland | Case description | Perinatal | Describe case of the first child being cared for by the perinatal hospice |

| Leong Marc-Aurele et al. [20] | US | Exploratory retrospective electronic chart review | Perinatal | Examine cases referred to a perinatal palliative care team |

| Leuthner 1 [63] | US | Program recommendations | Neonatal | Provide recommendations for general pediatricians on neonatal palliative care |

| Leuthner 2 [64] | US | Reflection on fetal palliative care | Perinatal | Describe whether the fetus is a patient to whom palliative care principles apply, and which patients can receive PPC |

| Leuthner et al. [65] | US | Program description | Perinatal | To review perinatal palliative care concepts and describe the perinatal palliative care program |

| Locatelli et al. [66] | Italy | Guideline description | Perinatal | Define guidelines to establish a new hospital policy for perinatal palliative care |

| Longmore [67] | New Zealand | Guideline description | Neonatal | Discuss new guidelines on neonatal palliative care |

| Martín-Ancela et al. [68] | Spain | Guideline description | Perinatal | Describe guidelines for Perinatal Palliative Care |

| Miller et al. [69] | US | Program recommendations | Perinatal | Provide recommendations for perinatal palliative comfort care |

| Moore et al. [70] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Munson et al. [71] | US | Program description | Neonatal | Framework for engaging families in perinatal palliative care discussions |

| National association of neonatal nurses board of directors [72] | US | Guideline description (position statement) | Neonatal | Position statement of the national association of neonatal nurses on neonatal palliative care |

| Nolte-Buchholtz et al. [73] | Germany | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program |

| Paize [74] | UK | Program description | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal palliative care program and children’s hospices |

| Ramer-Chrastek et al. [75] | US | Case study | Perinatal | Describe a perinatal hospice program |

| Roush et al. [76] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Description of a perinatal palliative care program |

| Rusalen et al. 2021 [77] | Italy | Literature review to propose shared care pathway | Perinatal | Propose a dedicated perinatal palliative care pathway |

| Rusalen [78] | Italy | Recommendation | Perinatal | Routinely employ a bioethical framework in end-of-life decision making |

| Ryan et al. [79] | US | Case study | Neonatal | Compare example with and without perinatal palliative care |

| Sidgwick et al. [9] | UK | Program description and case example | Perinatal | Describe a model for perinatal palliative care |

| Stringer et al. [80] | US | Guideline description | Perinatal | Provide information on perinatal palliative care |

| Thibeau et al. [81] | US | Reflection/literature overview | Neonatal | Standardize palliative care for both infants and their families |

| Tucker et al. [82] | US | Retrospective chart review | Perinatal | Describe received care in a PPC program, patient outcomes and attitudes of neonatologists |

| Uthaya et al. [83] | UK | Program description | Neonatal | Development of guideline for infants receiving palliative care |

| Wool et al. 2016 [8] | US | Cross sectional survey | Neonatal | Survey to describe existing PPC programs |

| Wool et al. 2020 [84] | US | Program description | Neonatal | Describe a PPC care program: history and recommendations |

| Ziegler et al. [85] | US | Program description | Perinatal | Describe development and processes of a PPC care program |

| Components | Subcomponents and Description | Times Mentioned |

|---|---|---|

| Practical organization of a perinatal palliative care team | ||

| PPC team members | Core team members:

| N: 47 [4,8,9,11,14,15,18,19,20,26,27,28,29,30,31,33,34,35,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,48,52,53,54,56,59,62,65,68,69,71,73,74,75,76,77,78,80,81,82,84,85] |

Members included when needed:

| N: 18 [9,11,18,26,27,28,29,33,34,35,42,44,54,56,68,69,84,85] | |

| Activation of the perinatal palliative care team | Which families and/or infants are eligible? Several programs discussed the inclusion criteria for contacting/starting up the perinatal palliative care program, including severe prenatal diagnosis, (extremely) premature infants, and neonates with severe conditions diagnosed after birth. | N: 24 [11,26,27,28,29,30,33,34,35,36,39,42,44,50,53,57,60,68,69,72,75,76,77,82] |

| Provide perinatal palliative care irrespective of the decision made: some programs indicated their involvement in case of a severe prenatal and/or neonatal diagnosis irrespective of whether curative treatment was still sought, or palliative options were being considered. | N: 11 [4,40,57,61,65,68,72,73,74,75,77] | |

| Provide place and/or circumstances for palliative care |

| N: 31 [8,11,18,34,35,39,43,44,47,48,51,52,53,54,55,56,62,63,64,65,66,69,71,72,74,76,77,81,83,84,85] |

| A step-by-step plan to organize palliative care | Provide a checklist of steps to take in caring for families in the PPC program. Including a fixed moment to start up PPC. | N: 21 [4,11,14,15,28,30,31,33,35,39,44,46,48,52,56,66,68,74,76,80,83] |

| Organization of communication between the care team | Provide a fixed way to share information with all involved, for example by using the patients electronic form or a separate shared document. Provide a clear and detailed way of documenting all conversations and decisions made; for example by using a fixed filing system or documentation system to record provided care. | N: 40 [4,8,9,11,14,15,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,37,39,41,42,44,46,49,50,52,53,54,58,59,66,67,68,69,71,73,74,75,76,77,81,85] |

| Ensure regular and multiple multidisciplinary meetings with the entire care team, to keep everyone involved up to date. Ensure that all information is passed so that parents do not have to repeat information multiple times (continuity of care). | N: 21 [9,11,14,26,29,30,41,43,44,54,59,66,67,69,71,77,78,81,82,83,85] | |

| Teaching of staff members | Organize formal training, for example on:

| N: 31 [4,8,11,14,15,30,31,33,34,36,38,39,44,46,47,48,50,52,53,54,55,59,60,61,66,67,68,78,81,84,85] |

Organize on the job training, for example by:

| N: 8 [11,31,36,39,46,52,54,84] | |

| Set up a collaboration with hospice or palliative home-care services |

| N: 34 [4,8,9,11,26,28,33,34,35,36,38,41,43,44,48,49,52,54,56,58,59,61,63,64,69,71,72,73,74,76,77,83,84,85] |

| A regular audit of the perinatal palliative care approach | Several programs mentioned a regular revision of the perinatal palliative care pathway to ensure that the team can work as efficiently as possible, and new insights are being incorporated into the palliative care approach. | N: 2 [11,34] |

| Fundraising for the program | Several programs mentioned the need for perinatal palliative care to be freely available to all families regardless of the costs accompanied by providing care. Therefore, fundraising for the program was sometimes discussed as being part of the perinatal palliative care program. | N: 4 [4,31,54,76] |

| Community awareness and involvement | Offer correct knowledge on palliative care, inform the public on how they can aid in supporting families going through perinatal loss. | N: 3 [60,70,78] |

| Care components of the perinatal palliative care program | ||

| Child-directed care | ||

| Care of the child preceding death | Ensuring comfort of the child (non-medical)

| N: 40 [4,8,11,14,18,19,26,27,28,34,36,38,39,41,43,45,46,47,48,49,52,53,54,55,56,58,63,64,66,68,69,72,73,74,76,77,80,83,84,85] |

Adequate pain/symptom management

| N: 46 [4,8,11,14,15,18,19,26,28,32,34,36,38,39,41,43,45,47,48,49,52,53,54,55,56,58,59,61,63,64,65,66,68,69,71,72,73,74,76,77,80,81,82,83,84,85] | |

| Food/nutrition and hydration: evaluate the need for oral, parenteral and enteral nutrition. There is discussion on whether artificial food and nutrition should continue to be provided. Breastfeeding is always considered as beneficial when the child is able to. | N: 27 [8,11,18,27,28,32,34,39,48,52,54,55,56,58,61,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,73,76,77,83,84] | |

Other care provided to the child

| N: 41 [4,8,11,15,18,26,27,28,31,32,34,36,38,39,41,42,45,46,47,48,52,53,54,55,56,59,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,72,73,76,77,80,83,84,85] | |

| Care of the child after death | Care of the body: bring body to the morgue or mortuary, provide visiting options for the parents/family after death, options to cool and rewarm the body. | N: 20 [4,11,28,31,38,39,42,43,47,50,52,53,63,64,65,68,74,76,77,83] |

| Post-mortem medical procedures |

| N: 25 [4,8,9,11,31,32,34,39,41,47,48,52,55,58,60,63,64,65,68,71,74,76,77,83,85] |

| Family-directed care | ||

| Maternal care | Delivery care: ensure maternal comfort, pain management and support. Healthcare providers present during the birth to support the mother and to confirm the diagnosis. | N: 13 [4,26,28,34,42,48,53,55,59,61,65,71,75] |

| Post-partum care: provide adequate post-partum care, including appropriate duration of hospital stay, providing care and pain relief, providing a lactation consultant, offer the possibility of donating breast milk, etc. | N: 16 [4,11,28,32,34,35,40,44,48,52,59,61,72,79,81,83] | |

| Family-centered care | Adapt care to the values, hopes, needs and cultural background of the family. Provide very individually tailored care. This includes providing a translator when needed. | N: 46 [4,8,9,11,26,27,28,29,31,33,34,35,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,53,54,56,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,75,77,80,81,82,84,85] |

| Promote family bonding and parenting | Allow for family bonding:

| N: 58 [4,8,11,18,20,26,27,28,29,31,33,34,35,36,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,79,80,81,83,84,85] |

Promote parenting:

| N: 39 [4,8,11,18,27,28,31,34,35,36,38,39,42,44,45,46,47,48,52,53,54,55,58,61,62,63,64,65,66,68,69,71,72,74,76,77,79,80,85] | |

| Respect families’ wishes not to bond. Provide encouragement to participate in care and bonding, but do not push family members who are not willing to bond. | N: 3 [38,52,53] | |

| Family-centered psychosocial support | Constant availability of psychosocial support

| N: 61 [4,8,11,14,19,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,81,82,83,84,85] |

Bereavement support:

| N: 43 [4,8,11,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,39,40,41,42,44,46,48,51,52,53,54,55,57,59,60,63,64,65,68,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,79,81,83,84,85] | |

| Religious and/or spiritual support: assess the need for spiritual support and cultural rituals/traditions. Allow for rituals and ceremonies. | N: 49 [4,8,11,14,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,38,39,41,42,43,44,46,47,48,49,52,53,54,55,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,75,76,77,79,80,83,84,85] | |

| Practical support | Aid in funeral planning and registering birth and death of the child. Inform, or aid parents in informing other authorities and organizations: family services, birth registries, etc., so parents do not have to make the call. | N: 33 [4,8,11,19,29,31,32,38,41,43,44,45,46,48,52,53,54,58,59,60,63,64,65,68,69,70,71,74,75,76,81,83,85] |

| Healthcare provider directed care | ||

| Support for healthcare providers | Formal support for healthcare providers: Provide psychological support during working hours, for example by a psychologist, ethics consultant, psychiatry staff, social workers, etc. | N: 15 [11,20,31,33,51,52,53,59,60,61,68,69,72,81,83] |

Informal support for healthcare providers

| N: 8 [11,52,54,67,68,79,80,83] | |

| Debriefings after death | Time to reflect on what happened and address possible conflicts, problems and issues. | N: 13 [11,33,44,52,53,54,55,59,67,72,77,80,83] |

| Relieve PPC members of other tasks when caring for an infant in their final moments | Make sure that the infant and the family is cared for by fixed staff members (nurses, physicians, etc.) who are available at all times during the dying process. This is often achieved by relieving them of caring for multiple other patients during this time. | N: 5 [31,38,44,53,80] |

| Advance care planning | ||

| Care plan during pregnancy and/or life of the child | Prenatal care plan

| N: 23 [4,28,29,32,34,42,48,49,54,55,56,59,60,61,68,69,71,74,75,77,78,84,85] |

Birth plan

| N: 44 [4,9,18,20,26,28,29,31,33,34,35,37,40,41,42,44,48,49,50,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,66,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,82,85] | |

Neonatal care plan

| N: 36 [4,8,9,18,20,26,28,33,34,37,38,41,42,44,49,54,56,58,60,61,63,64,65,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,82,84,85] | |

| Death plan |

| N: 13 [4,11,20,31,33,34,52,63,68,72,76,77,83] |

| Regular revisions of the care plan | Option to reassess/change the plan at any time. Needed when time passes, when new diagnostic and/or prognostic information becomes available, when the medical situation of the child improves or deteriorates, or when family and/or healthcare providers change their minds. | N: 12 [9,18,26,34,37,39,44,49,54,69,74,76] |

| Components regarding the decision-making process with parents/family members | ||

| Which information is shared? | Information regarding diagnosis and prognosis: be honest and open about the expected outcomes and what this means in terms of survival and morbidity. Be honest about possible diagnostic and/or prognostic uncertainty. | N: 49 [4,8,9,11,14,18,26,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,41,42,43,44,47,48,49,50,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,68,69,70,71,74,76,77,79,81,83,84,85] |

| Prepare parents for the death, educate them on what to expect (for example, gasping) | N: 24 [4,11,28,34,36,37,38,39,41,47,48,52,53,54,55,58,59,63,64,65,70,76,77,83] | |

| Provide the parents with regular updates regarding the diagnosis and prognosis, or if new information becomes available. | N: 18 [8,11,26,28,29,34,38,42,43,44,47,52,53,54,69,76,81,84] | |

| Raise topics for discussion in family meetings when parents leave them open | N: 2 [52,54] | |

| Provide all possible treatment options and consequences so that parents can make an informed decision. | N: 25 [4,9,11,14,34,37,40,41,42,47,49,57,59,61,64,65,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,77] | |

| Manner of sharing information | Schedule regular, planned, formal consultations with parents. Include all relevant members of the multidisciplinary team in order to adequately inform parents. Make sure someone is (almost) always available for questions. | N: 54 [4,8,9,11,14,15,19,20,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,38,40,41,42,43,44,47,48,49,52,53,54,55,56,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,75,76,77,78,80,81,82,83,84] |

Provide understandable information tailored to the parents:

| N: 30 [8,9,26,33,34,35,38,41,42,43,44,47,49,52,53,54,55,61,63,64,66,67,69,71,73,76,77,79,83,84] | |

Communication tailored to the parents’ needs, values and wishes:

| N: 31 [8,9,11,26,29,31,33,34,35,38,43,44,47,48,49,52,53,54,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,74,77,81,83,84] | |

| Make sure a private and comfortable room is provided for conversations with parents. | N: 15 [11,34,39,41,47,48,52,53,54,55,67,69,76,81,83] | |

| Shared decision making | Make decisions together with parents. Inquire about the role parents would like to play in decision making and respect them not willing to participate in decision making if this is the case. Support patient (parent) advocacy and empower parents to participate in decision making. | N: 18 [8,9,11,28,34,35,38,39,47,49,53,54,55,68,69,74,77,79] |

| Conflict resolution | When conflict between parents and healthcare providers occurs, aim to resolve this conflict by:

| N: 7 [11,34,53,60,69,81,83] |

Conflict resolution between healthcare providers in the team.

| N: 6 [9,11,53,77,81,83] | |

| Care for externals | ||

| Care for other families at the ward |

| N: 1 [53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dombrecht, L.; Chambaere, K.; Beernaert, K.; Roets, E.; De Vilder De Keyser, M.; De Smet, G.; Roelens, K.; Cools, F. Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review. Children 2023, 10, 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030482

Dombrecht L, Chambaere K, Beernaert K, Roets E, De Vilder De Keyser M, De Smet G, Roelens K, Cools F. Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review. Children. 2023; 10(3):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030482

Chicago/Turabian StyleDombrecht, Laure, Kenneth Chambaere, Kim Beernaert, Ellen Roets, Mona De Vilder De Keyser, Gaëlle De Smet, Kristien Roelens, and Filip Cools. 2023. "Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review" Children 10, no. 3: 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030482

APA StyleDombrecht, L., Chambaere, K., Beernaert, K., Roets, E., De Vilder De Keyser, M., De Smet, G., Roelens, K., & Cools, F. (2023). Components of Perinatal Palliative Care: An Integrative Review. Children, 10(3), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030482