A Self-Regulation Intervention Conducted by Teachers in a Disadvantaged School Neighborhood: Implementers’ and Observers’ Perceptions of Its Impact on Elementary Students

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. SRL: Theoretical Framework

1.2. SRL Interventions for Elementary Students: What Seems to Work?

1.3. The “Yellow Trails and Tribulations” Narrative-Based Intervention

1.4. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Treatment Integrity

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

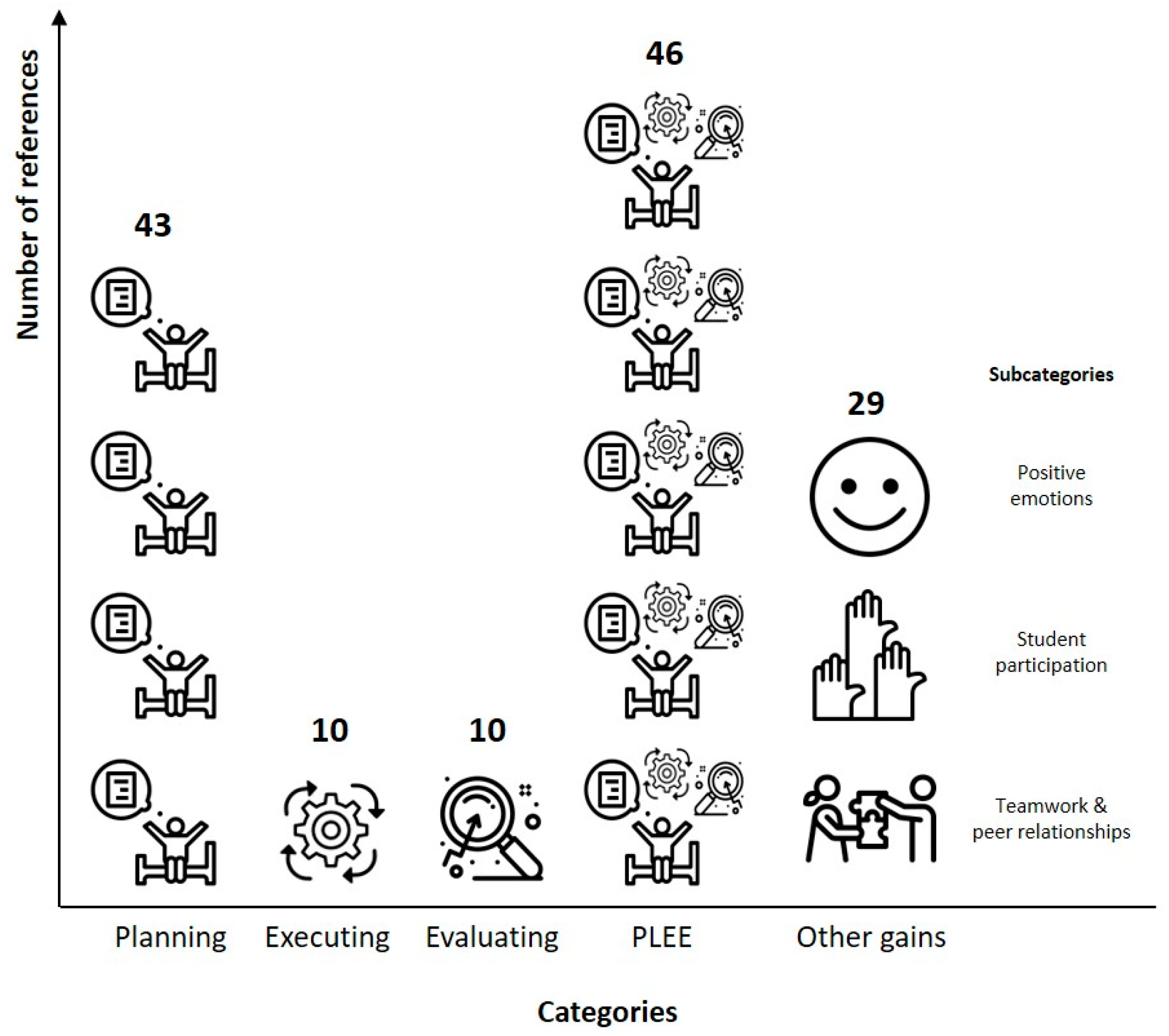

3. Results

3.1. Planning Phase

3.2. Execution Phase

3.3. Evaluation Phase

3.4. PLEE

“On the weekend, I planned a trip to the beach, and I was the one who helped my mother to plan. I made a list of what we would need and the games and activities we wanted to do. The picnic was planned, not forgetting the bag to put the rubbish in. We did everything we planned, and in the end, we concluded that we forgot nothing because we used PLEE—C told” (C2SS7).

3.5. Other Gains

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

4.2. Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Session | Chapter(s) | Brief Descriptions of the Chapter(s) of the “Yellow Trials and Tribulations” Narrative [44] | Major Goal(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Introduction of the story: Story setting (e.g., Never-Ending Forest and the living beings that live there, where everyone helps each other and everything works together perfectly), and psychological description of the main characters (i.e., colors of the rainbow). |

|

| 2 | 2 | Presentation of the problem: The color Red notices that Yellow disappeared from the rainbow. The colors become worried and disorganized without knowing what to do. The Lizard Stone used to say, “There is a place for everything, and everything must be in its place” (p. 12). The color Red suggests searching for their friend Yellow. The color Green suggests that they could ask for help from the Hiccup River because he could know what to do. |

|

| 3 | 3 | The Hiccup River advises the colors not to give up and provides a clue: they should plan well what to do. The colors do not know what planning means. The Smiling Eagle appears and explains the meaning of planning and provides an example of its application when hunting a rabbit. |

|

| 4 | 4 | The Teacher-Bird teaches a group of little birds how to fly, telling them that “learning more and better depends on what each one does” (p. 20) and “no one learns how to fly with the wings closed” (p. 21). The Teacher-Bird tells the story of the school of deer. One student deer does not want to jump or run and ends up being too heavy to jump and run in the woods. One day, he hurts his leg while competing with a grasshopper. |

|

| 5 | 5 | The color Orange finds a message from Yellow (i.e., a chicken-shaped paper). The color Violet says they need to make a plan, and Green recalls that they need to prepare and think well about what to do before leaving, as the Smiling Eagle taught them. The colors start planning, and his friend, Squirrel, says, “To reach the top of a tree, you have to start climbing, but climbing one branch at a time” (p. 25). After a long journey with many challenges, the colors stop to rest. |

|

| 6 | 6 and 7 | When the colors are resting, the attentive color, Violet, notices an army of ants passing by, and calls his friends (Chapter 6). The color Red asks the General-Ant whether someone saw Yellow. The General-Ant explains how the Ant Army follows the PLEE model and monitors their work. The colors recall the Teacher-Bird’s lessons. The colors find a quicksand swamp—an excellent opportunity to apply what they have learned from the Smiling Eagle and the General-Ant (Chapter 7). The colors set a strategy to achieve their goal (i.e., reach the other side of the swamp) and work together. The colors monitor their strategy step by step. The color Red uses a new strategy to overcome an obstacle, and the other colors help. |

|

| 7 | 9 and 10 | The color Blue finds the second message from Yellow—another chicken-shaped paper (Chapter 9). The colors continue their journey, walking many leagues, and when they stop to rest, they notice the preparation of the picnic of problems. At that picnic, there is a contest for the “Emperor of Problems”, and the main candidates are lies, laziness, pout, disobedience, and fear (Part I). The candidates present themselves and the arguments to be the “Emperor of Problems”. The contest for the “Emperor of Problems” takes place (Part II, Chapter 10). The color Violet finds a new message from Yellow (i.e., a chicken-shaped paper). The color Anil, who always pays attention to details, notices that the chicken-shaped paper is smaller than the previous one. The Smiling Eagle asks the colors how their PLEE is going and advises them to be careful of the danger in their way. |

|

| 8 | 13 and 14 | The colors find the Pirate-Tree, which says that a message from Yellow is hidden in its branches (Chapter 13). However, the Pirate-Tree only shows the message if the colors unravel three riddles. The colors set various strategies and work together. The colors are successful in unraveling all of the riddles, and the Pirate-Tree becomes very angry because of that. The colors ask the Pirate-Tree to give them the message from Yellow (Chapter 14). The Pirate-Tree reveals that the message is hidden in a hollow trunk. The colors wonder why the tree lied and assess the situation to decide what to do. After a first inspection of the trunk, they notice that a large spider guards it. The colors use PLEE again (setting different strategies) to overcome the new challenge. The colors obtain the message from Yellow, which is smaller than the last one, and try to unravel the reason. |

|

| 9 | 15 and 16 | The colors sleep during the night, but their friend, Squirrel, wakes up the color Blue because he hears a groan—it could be Yellow asking for help (Chapter 15). The color Blue and Squirrel decide to leave to find Yellow without telling someone. Despite difficulties (e.g., dark fears), the two friends find a little lark that belongs to the Royal Choir of the Birds. The Lark is injured, and the two friends try to help. The Lark is very talkative, telling how she is so distractive and saying that singing in the choir is very difficult and the Bird-Maestro is so demanding. The two friends ask the Lark to let them think about what to do. It dawns, and the colors notice that the color Blue and the Squirrel are not there (Chapter 16). The colors become worried and disorganized. The color Orange, staying calm, tells the story of Hansel and Gretel. The color Green understands the point that Orange makes and proposes a strategy: instead of bread, they could use torches. The colors find their two friends and the Lark easily. The colors become angry, and their friends ask for forgiveness for their thoughtless act. The most important thing is to recognize when we make a mistake, apologize, and try not to do it again. |

|

| 10 | 17 | The Smiling Eagle wakes the group very early in the morning and asks how their goal is going. The colors say that they have not found Yellow yet. The Smiling Eagle asks whether they found the four messages from Yellow, and the colors wonder how the Smiling Eagle knows that. The Smiling Eagle admits that it has the last message, and that Yellow was hidden near the chicken camp, but Yellow disappeared again. The color Violet tells everyone to be calm and to think using PLEE, and the colors set a new plan with other strategies until they find Yellow (note: location not revealed purposefully). The colors celebrate. The rainbow is complete, and everything returns to the way it was in the Never-Ending Forest. |

|

Appendix B

References

- Schunk, D.H.; Zimmerman, B.J. Social Origins of Self-Regulatory Competence. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 32, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. From Cognitive Modeling to Self-Regulation: A Social Cognitive Career Path. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 48, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruce, R.; Bol, L. Teacher Beliefs, Knowledge, and Practice of Self-Regulated Learning. Metacogn. Learn. 2015, 10, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G. Teachers’ Direct and Indirect Promotion of Self-Regulated Learning in Primary and Secondary School Mathematics Classes—Insights from Video-Based Classroom Observations and Teacher Interviews. Metacogn. Learn. 2018, 13, 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, M.J.; Vosniadou, S.; Van Deur, P.; Wyra, M.; Jeffries, D. Teachers’ and Students’ Belief Systems about the Self-Regulation of Learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2019, 31, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulano, C.; Cunha, J.; Núñez, J.C.; Pereira, B.; Rosário, P. Mozambican Adolescents’ Perspectives on the Academic Procrastination Process. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2018, 39, 196–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M.; Kuzucu, E. Academic Procrastination and Motivation of Adolescents in Turkey. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.M.; Newbegin, I. Academic Procrastination of Adolescents in English and Mathematics: Gender and Personality Variations. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2000, 15, 111–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Valle, A.; González-Pienda, J.; Lourenço, A. Grade Level, Study Time, and Grade Retention and Their Effects on Motivation, Self-Regulated Learning Strategies, and Mathematics Achievement: A Structural Equation Model. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 1311–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P. The Nature of Procrastination: A Meta-Analytic and Theoretical Review of Quintessential Self-Regulatory Failure. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Regulating Academic Learning and Achievement: The Emergence of a Social Cognitive Perspective. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 2, 173–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuffianò, A.; Alessandri, G.; Gerbino, M.; Luengo Kanacri, B.P.; Di Giunta, L.; Milioni, M.; Caprara, G.V. Academic Achievement: The Unique Contribution of Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Self-Regulated Learning beyond Intelligence, Personality Traits, and Self-Esteem. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2013, 23, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housand, A.; Reis, S.M. Self-Regulated Learning in Reading: Gifted Pedagogy and Instructional Settings. J. Adv. Acad. 2008, 20, 108–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peverly, S.T.; Brobst, K.E.; Graham, M.; Shaw, R. College Adults Are Not Good at Self-Regulation: A Study on the Relationship of Self-Regulation, Note Taking, and Test Taking. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Rosenbaum, J. Self-Regulation and the Income-Achievement Gap. Early. Child. Res. Q. 2008, 23, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Büttner, G. Components of Fostering Self-Regulated Learning among Students. A Meta-Analysis on Intervention Studies at Primary and Secondary School Level. Metacogn. Learn. 2008, 3, 231–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Rodríguez, C.; Cerezo, R.; Fernández, E.; Tuero, E.; Högemann, J. Analysis of Instructional Programs in Different Academic Levels for Improving Self-Regulated Learning SRL through Written Text. In Design Principles for Teaching Effective Writing, 1st ed.; Fidalgo, R., Harris, K., Braaksma, M., Eds.; Brill Editions: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 201–231. ISBN 978-90-04-27048-0. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, H.M. Commentary: Use of Evidence-Based Interventions in Schools: Where We’ve Been, Where We Are, and Where We Need to Go. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 33, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, D.; Torgerson, C.; Ainsworth, H.; Buckley, H.; Heaps, C.; Hewitt, C.; Mitchell, N. Improving Writing Quality—Evaluation Report and Executive Summary; Education Endowment Foundation: London, UK, 2014; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Gulbenkian Academies for Knowledge. Available online: https://cdn.gulbenkian.pt/academias/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2019/07/ACG_BrochuraEN.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Panadero, E. A Review of Self-Regulated Learning: Six Models and Four Directions for Research. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Attaining Self-Regulation. In Handbook of Self-Regulation; Boekaerts, M., Zeidner, M., Pintrich, P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 13–39. ISBN 978-0-12-109890-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B.J.; Campillo, M. Motivating Self-Regulated Problem Solvers; Davidson, J.E., Sternberg, R.J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Behavior Theory and the Models of Man (1974). In The Evolution of Psychology: Fifty Years of the American Psychologist; Notterman, J.M., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; pp. 154–172. ISBN 978-1-55798-473-9. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, E.; Pfuhl, G.; Sæle, R.G.; Svartdal, F.; Låg, T.; Dahl, T.I. Metacognition in Psychology. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2019, 23, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavell, J.H. Metacognition and Cognitive Monitoring: A New Area of Cognitive–Developmental Inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1979, 34, 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G.; Moshman, D. Metacognitive Theories. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 7, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G. Promoting General Metacognitive Awareness. Instr. Sci. 1998, 26, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlen, Y. Differences in Students’ Metacognitive Strategy Knowledge, Motivation, and Strategy Use: A Typology of Self-Regulated Learners. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Cunha, J.; Azevedo, R.; Pereira, R.; Nunes, A.R.; Fuentes, S.; Moreira, T. Promoting Gypsy Children School Engagement: A Story-Tool Project to Enhance Self-Regulated Learning. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2016, 47, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, A.; Muijs, D.; Stringer, E. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Guidance Report; Education Endowment Foundation: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. The Effectiveness of Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) Interventions on L2 Learning Achievement, Strategy Employment, and Self-Efficacy: A Meta-Analytic Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignath, C.; Buettner, G.; Langfeldt, H.-P. How Can Primary School Students Learn Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Most Effectively?: A Meta-Analysis on Self-Regulation Training Programmes. Educ. Res. Rev. 2008, 3, 101–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, M. Self-Regulated Learning Training Programs Enhance University Students’ Academic Performance, Self-Regulated Learning Strategies, and Motivation: A Meta-Analysis. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 66, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sperling, R.A. Characteristics of Effective Self-Regulated Learning Interventions in Mathematics Classrooms: A Systematic Review. Front. Educ. 2020, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, H.; Donker, A.S.; Kostons, D.D.N.M.; van der Werf, G.P.C. Long-Term Effects of Metacognitive Strategy Instruction on Student Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018, 24, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevelde, S.; Van Keer, H.; Merchie, E. The Challenge of Promoting Self-Regulated Learning among Primary School Children with a Low Socioeconomic and Immigrant Background. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 110, 113–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.T.; Wigfield, A.; Barbosa, P.; Perencevich, K.C.; Taboada, A.; Davis, M.H.; Scafiddi, N.T.; Tonks, S. Increasing Reading Comprehension and Engagement Through Concept-Oriented Reading Instruction. J. Educ. Psychol. 2004, 96, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.M.; Blythe, T.; White, N.; Li, J.; Gardner, H.; Sternberg, R.J. Practical Intelligence for School: Developing Metacognitive Sources of Achievement in Adolescence. Dev. Rev. 2002, 22, 162–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohn, R.L.; Frey, B. Heuristic Training and Performance in Elementary Mathematical Problem Solving. J. Educ. Res. 2002, 95, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, J.; Silva, C.; Guimarães, A.; Sousa, P.; Vieira, C.; Lopes, D.; Rosário, P. No Children Should Be Left Behind During COVID-19 Pandemic: Description, Potential Reach, and Participants’ Perspectives of a Project Through Radio and Letters to Promote Self-Regulatory Competences in Elementary School. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 647708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jager, B.; Jansen, M.; Reezigt, G. The Development of Metacognition in Primary School Learning Environments. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. 2005, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, H.; Donker, A.S.; van der Werf, M.P.C. Effects of the Attributes of Educational Interventions on Students’ Academic Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2014, 84, 509–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.A. Sarilhos do Amarelo [Yellow’s Trials and Tribulations]; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2007; ISBN 978-972-0-72001-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.A. Auto-Regulação em Crianças Sub-10: Projecto Sarilhos do Amarelo; Porto Editora: Porto, Portugal, 2007; ISBN 978-972-0-96999-6. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, R.; Rosário, P.; Magalhães, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Pereira, B.; Pereira, A. A Tool-Kit to Help Students from Low Socioeconomic Status Background: A School-Based Self-Regulated Learning Intervention. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2022, 38, 495–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.; Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Fuentes, S.; Magalhães, P. A School-Based Intervention on Elementary Students’ School Engagement. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 73, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, O. Estórias Como Ferramentas Para Promover Competências de Auto-Regulação: Um Estudo No 4° ano de Escolaridade. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2009. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, J.C.; Tuero, E.; Fernández, E.; Añón, F.J.; Manalo, E.; Rosário, P. Effect of an Intervention in Self-Regulation Strategies on Academic Achievement in Elementary School: A Study of the Mediating Effect of Self-Regulatory Activity. Rev. Psicodidact. 2022, 27, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, P.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.A.; Valle, A. Enhancing primary school students self-regulated learning: Yellow’s trials and tribulations project. In International Perspectives on Applying Self-Regulated Learning in Different Settings; De la Fuente, J., Eissa, M.A., Eds.; Education & Psychology I+D+i: Almeria, Spain, 2010; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. The Explanatory and Predictive Scope of Self-Efficacy Theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1986, 4, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högemann, J. Promoção de Competências de Autorregulação Na Escrita: Um Estudo No 1. ° Ciclo Do Ensino Básico. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Minho, Braga, Portugal, 2011. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, P.; Högemann, J.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Cunha, J.; Rodríguez, C.; Fuentes, S. The Impact of Three Types of Writing Intervention on Students’ Writing Quality. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.; Miranda, S.; Teixeira, S.; Mesquita, S.; Zanatta, C.; Rosário, P. Promote Selective Attention in 4th-Grade Students: Lessons Learned from a School-Based Intervention on Self-Regulation. Children 2021, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuero, E.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Fernández, M.P.; Añón, F.J.; Moreira, T.; Martins, J.; Rosário, P. Short and Long-Term Effects on Academic Performance of a School-Based Training in Self-Regulation Learning: A Three-Level Experimental Study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 889201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Becoming a Self-Regulated Learner: An Overview. Theory Pract. 2002, 41, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Comission Recommendations of the European Parliament and the Council of 18 December 2006 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning 2006. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:394:0010:0018:en:PDF (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- European Comission Assessment of Key Competences in Initial Education and Training: Policy Guidance 2012. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=SWD:2012:0371:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Sala, A.; Punie, Y.; Garkov, V.; Cabrera, M. The European Framework for Personal, Social and Learning to Learn Key Competence 2020. Available online: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC120911 (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Martins, J.; Cunha, J.; Vilas, C.; Rosário, P. Voices of Mentee-Mentor Dyads: Impact of a School-Based Mentoring Support on Self-Regulation to Rescue Students Experiencing School Failure. In The Psychology of Self-Regulation; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2023; ISBN 979-8-88697-416-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nastasi, B.K.; Schensul, S.L. Contributions of Qualitative Research to the Validity of Intervention Research. J. Sch. Psychol. 2005, 43, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística Censos 2011. Available online: https://censos.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=CENSOS&xpgid=censos2011_apresentacao (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística Censos 2021. Available online: https://tabulador.ine.pt/censos2021/ (accessed on 21 April 2023).

- Retrato de Portugal em 2018|Pordata. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/Retratos/2018/Retrato+de+Portugal-74 (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Jones, C.; Shen, J. Neighborhood Social Capital, Neighborhood Disadvantage, and Change of Neighborhood as Predictors of School Readiness. Urban Stud. Res. 2014, 2014, 204583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Fischer, M.J. Advantaged/Disadvantaged School Neighborhoods, Parental Networks, and Parental Involvement at Elementary School. Sociol. Educ. 2017, 90, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.C.; Rosário, P.; Vallejo, G.; González-Pienda, J.A. A Longitudinal Assessment of the Effectiveness of a School-Based Mentoring Program in Middle School. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 38, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepletchikova, F. On the Topic of Treatment Integrity. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 18, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NVivo, Version 10; QSR International Pty Ltd.: Burlington, MA, USA, 2014.

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterman, D.K. The Case for the Prosecution: Transfer as an Epiphenomenon. In Transfer on Trial: Intelligence, Cognition, and Instruction; Ablex Publishing: Westport, CT, USA, 1993; pp. 1–24. ISBN 978-0-89391-825-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bonotto, C.; Basso, M. Is It Possible to Change the Classroom Activities in Which We Delegate the Process of Connecting Mathematics with Reality? Int. J. Math. Educ. Sci. Technol. 2001, 32, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bransford, J.D.; Barron, B.; Pea, R.D.; Meltzoff, A.; Kuhl, P.; Bell, P.; Stevens, R.; Schwartz, D.L.; Vye, N.; Reeves, B.; et al. Foundations and Opportunities for an Interdisciplinary Science of Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; Sawyer, R.K., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 19–34. ISBN 978-0-521-60777-3. [Google Scholar]

- Furrer, C.J.; Skinner, E.A.; Pitzer, J.R. The Influence of Teacher and Peer Relationships on Students’ Classroom Engagement and Everyday Motivational Resilience. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2014, 116, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, A.Y.; Ruzek, E.A.; Hafen, C.A.; Gregory, A.; Allen, J.P. Perceptions of Relatedness with Classroom Peers Promote Adolescents’ Behavioral Engagement and Achievement in Secondary School. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 2341–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosan, N.E.; Hoglund, W. Do Teacher–Child Relationship and Friendship Quality Matter for Children’s School Engagement and Academic Skills? Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 46, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Cappella, E. Mapping the Social World of Classrooms: A Multi-Level, Multi-Reporter Approach to Social Processes and Behavioral Engagement. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2016, 57, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, E.; Archambault, I.; Dupéré, V. Boys’ and Girls’ Latent Profiles of Behavior and Social Adjustment in School: Longitudinal Links with Later Student Behavioral Engagement and Academic Achievement? J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 69, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, E.A.; Pitzer, J.R. Developmental Dynamics of Student Engagement, Coping, and Everyday Resilience. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 21–44. ISBN 978-1-4614-2018-7. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, E.; Furrer, C.; Marchand, G.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and Disaffection in the Classroom: Part of a Larger Motivational Dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Blumenfeld, P.C.; Paris, A.H. School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2004, 74, 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shernoff, D.J.; Ruzek, E.A.; Sinha, S. The Influence of the High School Classroom Environment on Learning as Mediated by Student Engagement. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2017, 38, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Liem, G.A.D.; Martin, A.J.; Colmar, S.; Marsh, H.W.; McInerney, D. Academic Motivation, Self-concept, Engagement, and Performance in High School: Key Processes from a Longitudinal Perspective. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumberger, R.W. High School Dropouts in the United States. In School Dropout and Completion: International Comparative Studies in Theory and Policy; Lamb, S., Markussen, E., Teese, R., Polesel, J., Sandberg, N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 275–294. ISBN 978-90-481-9763-7. [Google Scholar]

- Shernoff, D.J. Optimal Learning Environments to Promote Student Engagement; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-7088-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mussweiler, T. Comparison Processes in Social Judgment: Mechanisms and Consequences. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.A.; Malloy, J.A.; Parsons, A.W.; Burrowbridge, S.C. Students’ Engagement in Literacy Tasks. Read. Teach. 2015, 69, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.A.; Malloy, J.A.; Parsons, A.W.; Peters-Burton, E.E.; Burrowbridge, S.C. Sixth-Grade Students’ Engagement in Academic Tasks. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 111, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-T.; Amemiya, J. Changing Beliefs to Be Engaged in School: Using Integrated Mindset Interventions to Promote Student Engagement during School Transitions. In Handbook of Student Engagement Interventions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 169–182. ISBN 978-0-12-813413-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ing, M.; Webb, N.M.; Franke, M.L.; Turrou, A.C.; Wong, J.; Shin, N.; Fernandez, C.H. Student Participation in Elementary Mathematics Classrooms: The Missing Link between Teacher Practices and Student Achievement? Educ. Stud. Math. 2015, 90, 341–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, T.J.; Zimmerman, B.J. A Cyclical Self-Regulatory Account of Student Engagement: Theoretical Foundations and Applications. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 237–257. ISBN 978-1-4614-2018-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pino-James, N.; Shernoff, D.J.; Bressler, D.M.; Larson, S.C.; Sinha, S. Chapter 8—Instructional Interventions That Support Student Engagement: An International Perspective. In Handbook of Student Engagement Interventions; Fredricks, J.A., Reschly, A.L., Christenson, S.L., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 103–119. ISBN 978-0-12-813413-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wigfield, A.; Eccles, J.S. Expectancy–Value Theory of Achievement Motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidi, S.; Renninger, K.A. The Four-Phase Model of Interest Development. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 41, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.C.; Simão, A.M.V.; da Silva, A.L. Does Training in How to Regulate One’s Learning Affect How Students Report Self-Regulated Learning in Diary Tasks? Metacognition Learn. 2015, 10, 199–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Clark, V. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Los Angeles, OH, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4833-4437-9. [Google Scholar]

- Salomon, G.; Perkins, D.N. Rocky Roads to Transfer: Rethinking Mechanism of a Neglected Phenomenon. Educ. Psychol. 1989, 24, 113–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.; Simões, C.; Cefai, C.; Freitas, E.; Arriaga, P. Emotion Regulation and Student Engagement: Age and Gender Differences during Adolescence. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 109, 101830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.; Rosário, P.; Cunha, J.; Núñez, J.C.; Vallejo, G.; Moreira, T. How to Help Students in Their Transition to Middle School? Effectiveness of a School-Based Group Mentoring Program Promoting Students’ Engagement, Self-Regulation, and Goal Setting. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Herlitz, L.; MacIntyre, H.; Osborn, T.; Bonell, C. The Sustainability of Public Health Interventions in Schools: A Systematic Review. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Liang, Y. How School Principals’ Motivating Style Stimulates Teachers’ Job Crafting: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 20833–20848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cece, V.; Martinent, G.; Guillet-Descas, E.; Lentillon-Kaestner, V. The Predictive Role of Perceived Support from Principals and Professional Identity on Teachers’ Motivation and Well-Being: A Longitudinal Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | Preparing something. Process of “thinking before doing something”, which involves defining what, when, where, how, and with whom [44,45]. This phase implies setting a plan, goals, and strategies [50]. | |

| Executing | Doing something as planned before (e.g., using the materials and strategies selected, put the plan into practice in the time defined [50]). The process of “thinking while doing something” involves monitoring to check whether everything goes as planned [44,45]. This phase implies persistence and attention focusing. | |

| Evaluating | Examining something finished. Process of “thinking after doing something”, which involves assessing whether something was accomplished as planned (e.g., completely as planned or whether there were delays [44,45]). This phase implies considering the reasons for a given result, positive or negative [50]. | |

| PLEE | Cycle of three phases: planning, executing, and evaluating [50]. Its application involves mentioning at least one aspect of each phase of the PLEE model. | |

| Other gains | Teamwork and improved peer relationships | Recognizing the importance of working together collaboratively; having more friends; decrease peer conflicts; respect and warmth between classmates. |

| Student participation | Frequency and quality of student participation during sessions and class discussions; positive classroom behaviors. | |

| Positive emotions | Feelings of joy, happiness, pride, and enthusiasm regarding school, school tasks, intervention, and performance. | |

| Class (Code) | Session Sheets | Final Report | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

| 1 | --- | Planification | Planification | Planification Other gains | Planification Evaluation Other gains | Planification Execution PLEE | PLEE | Planification Execution Evaluation PLEE Other gains | Planification Evaluation PLEE | PLEE Other gains | PLEE Other gains |

| 2 | --- | Other gains | Planification | --- | Planification | Planification Evaluation PLEE | PLEE | Planification Evaluation PLEE | Planification PLEE | Planification PLEE | PLEE Other gains |

| 3 | --- | --- | Planification | --- | --- | Planification | PLEE | PLEE | PLEE | Planification | --- |

| 4 | Other gains | Other gains | Planification | Planification | Planification | Planification | PLEE | Planification Execution Evaluation PLEE | Planification Execution PLEE | Planification Execution PLEE | PLEE Other gains |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, J.; Guimarães, A.; Martins, J.; Rosário, P. A Self-Regulation Intervention Conducted by Teachers in a Disadvantaged School Neighborhood: Implementers’ and Observers’ Perceptions of Its Impact on Elementary Students. Children 2023, 10, 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111795

Cunha J, Guimarães A, Martins J, Rosário P. A Self-Regulation Intervention Conducted by Teachers in a Disadvantaged School Neighborhood: Implementers’ and Observers’ Perceptions of Its Impact on Elementary Students. Children. 2023; 10(11):1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111795

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Jennifer, Ana Guimarães, Juliana Martins, and Pedro Rosário. 2023. "A Self-Regulation Intervention Conducted by Teachers in a Disadvantaged School Neighborhood: Implementers’ and Observers’ Perceptions of Its Impact on Elementary Students" Children 10, no. 11: 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111795

APA StyleCunha, J., Guimarães, A., Martins, J., & Rosário, P. (2023). A Self-Regulation Intervention Conducted by Teachers in a Disadvantaged School Neighborhood: Implementers’ and Observers’ Perceptions of Its Impact on Elementary Students. Children, 10(11), 1795. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10111795