Percutaneous Drug Delivery to the Masticatory System: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Objectives

2. Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Processes

2.4. Data Items and Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.5. Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

2.6. Registration and Protocol

3. Results

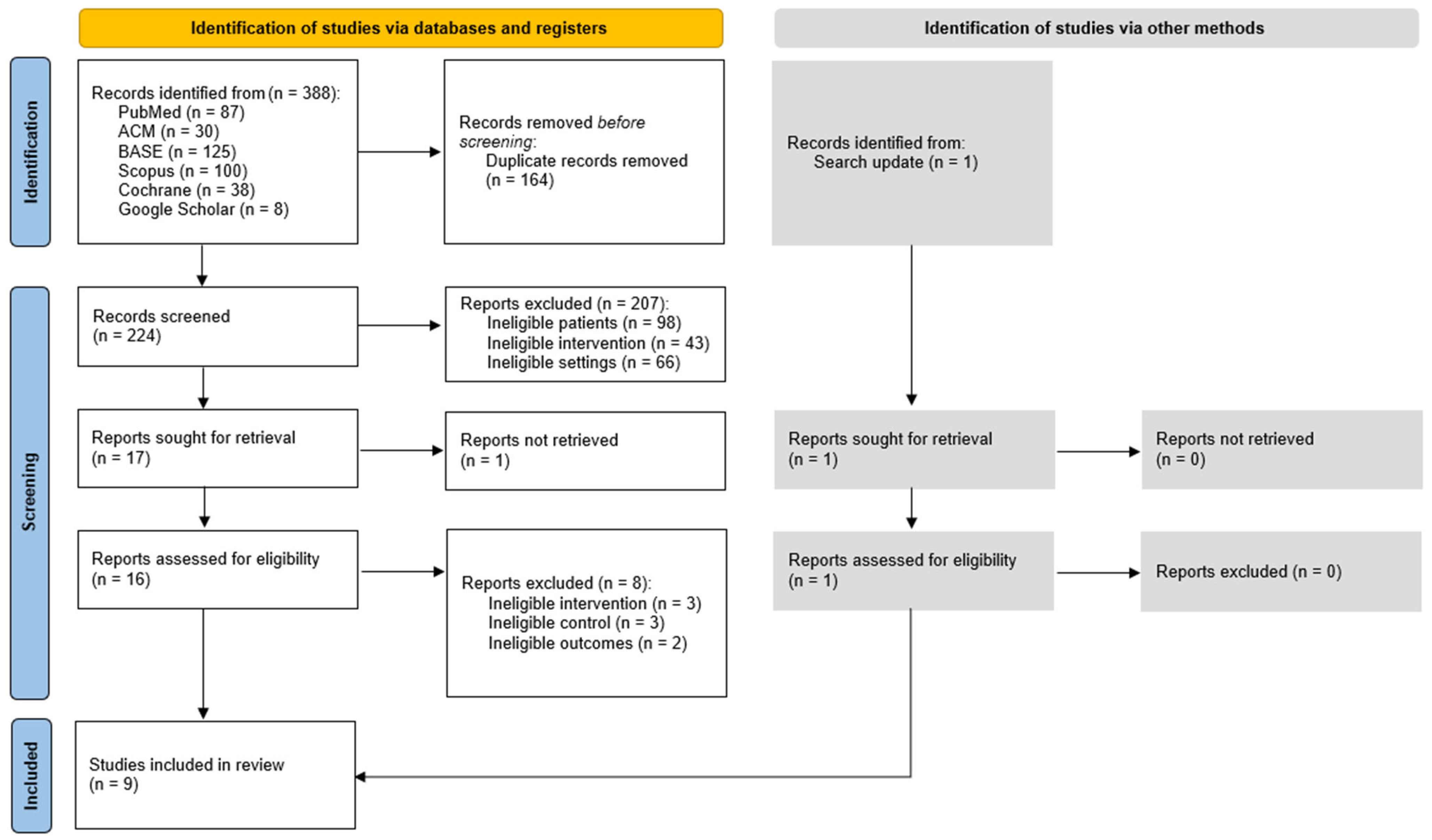

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.5. Results of Syntheses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| DC/TMD | Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis |

| SC | Stratum Corneum |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SE | Standard Error |

| THC | Tetrahydrocannabinol |

| TMD | Temporomandibular Disorders |

| TMJ | Temporomandibular Joint |

| VAS | Visual Analog Scale |

Appendix A

- Search string

- (temporomandibular OR TMD OR TMJ) AND (muscular OR muscle OR masseter OR temporal OR temporalis OR pterygoid) AND (percutaneous OR transdermal OR per-mucosal OR transmucosal OR topical OR dermal OR mucosal OR epidermal OR surface OR delivery) AND (randomized OR random OR randomly)

| First Author, Publication Year | Title | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Svensson P, 1997 [76] | Effect of systemic versus topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on post-exercise jaw-muscle soreness: a placebo-controlled study | Report not retrieved |

| L Di Rienzo Businco, 2004 [77] | Topical versus systemic diclofenac in the treatment of temporo-mandibular joint dysfunction symptoms | Ineligible intervention: systemic treatment |

| E C Ekberg, 1996 [78] | Diclofenac sodium as an alternative treatment of temporomandibular joint pain | Ineligible intervention: systemic treatment |

| Insha Azam, 2023 [79] | Effects of a program consisting of strain/counterstain technique, phonophoresis, heat therapy, and stretching in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction—PMC | Ineligible control: no control group |

| K Matsumoto, 2014 [80] | Local application of Aqua Titan improves symptoms of temporomandibular joint muscle disorder: a preliminary study | Ineligible control: no control group |

| Al-Zuheri, Insam, 2014 [81] | The Effect of Topical Anesthesia on Jaw Pain Thresholds in Patients with Generalized Pain | Ineligible outcomes: pressure pain threshold |

| Jerner, Adéle, 2014 [82] | The Effect of Topical Anesthesia on Pain Perception in Patients with Local Myalgia | Ineligible outcomes: pressure pain threshold |

| Schiffman EL, 1996 [83] | Temporomandibular joint iontophoresis: a double-blind randomized clinical trial | Ineligible outcomes: non-quantifiable results |

| Costa YM, 2020 [84] | Topical anesthesia degree is reduced in temporomandibular disorders patients: A novel approach to assess underlying mechanisms of the somatosensory alterations | Ineligible control: healthy volunteers |

| First Author, Publication Year | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walczyńska-Dragon K, 2024 [33] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2019 [34] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Ramakrishnan SN, 2019 [35] | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns |

| Campbell BK, 2017 [36] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some Concerns | Some concerns |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2014 [37] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Li LC, 2009 [38] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Lobo SL, 2004 [39] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Winocur E, 2000 [40] | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low | Low | Some concerns |

| Shin SM, 1997 [41] | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

References

- Alomar, X.; Medrano, J.; Cabratosa, J.; Clavero, J.A.; Lorente, M.; Serra, I.; Monill, J.M.; Salvador, A. Anatomy of the Temporomandibular Joint. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2007, 28, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helland, M.M. Anatomy and Function of the Temporomandibular Joint. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1980, 1, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaffer, S.M.; Brismée, J.-M.; Sizer, P.S.; Courtney, C.A. Temporomandibular Disorders. Part 1: Anatomy and Examination/Diagnosis. J. Man. Manip. Ther. 2014, 22, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koolstra, J.H. Dynamics of the Human Masticatory System. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2002, 13, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeResche, L. Epidemiology of Temporomandibular Disorders: Implications for the Investigation of Etiologic Factors. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 1997, 8, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miettinen, O.; Lahti, S.; Sipilä, K. Psychosocial Aspects of Temporomandibular Disorders and Oral Health-Related Quality-of-Life. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2012, 70, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, V.; Monteiro, L.; Orge, C.; Sales, M.; Melo, J.; Rodrigues, B.; Melo, A. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Disorders in the Brazilian Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. CRANIO® 2023, 43, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, E.; Fricton, J. Epidemiology of TMJ and Craniofacial Pains: An Unrecognized Societal Problem. In TMJ and Craniofacial Pain: Diagnosis and Management; Fricton, J.R., Kroening, R.J., Hathaway, K.M., Eds.; Ishiyaku EuroAmerica: St. Louis, MI, USA, 1988; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M.A.; Hall, E.H. A Comparison of the Signs of Temporomandibular Joint Dysfunction and Occlusal Discrepancies in a Symptom-Free Population of Men and Women. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1990, 70, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, I.-M.; List, T.; Drangsholt, M. Headache and Co-Morbid Pains Associated with TMD Pain in Adolescents. J. Dent. Res. 2013, 92, 802–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitiniene, D.; Zamaliauskiene, R.; Kubilius, R.; Leketas, M.; Gailius, T.; Smirnovaite, K. Quality of Life in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. A Systematic Review. Stomatologija 2018, 20, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jewair, T.; Shibeika, D.; Ohrbach, R. Temporomandibular Disorders and Their Association with Sleep Disorders in Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2021, 35, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventafridda, V.; Saita, L.; Ripamonti, C.; De Conno, F. WHO Guidelines for the Use of Analgesics in Cancer Pain. Int. J. Tissue React. 1985, 7, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anekar, A.A.; Hendrix, J.M.; Cascella, M. WHO Analgesic Ladder. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Riemsma, R.; Forbes, C.A.; Harker, J.; Worthy, G.; Misso, K.; Schaefer, M.; Kleijnen, J.; Stuerzebecher, S. Systematic Review of Tapentadol in Chronic Severe Pain. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2011, 27, 1907–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers, A. The Management of Acute Pain. Surg. Oxf. Int. Ed. 2010, 28, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E. The World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder. J. Midwife Womens Health 2004, 49, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzyńska, K. Ból jako jeden z głównych problemów osób leczonych operacyjnie. Innow. Pielęgniarstwie Nauk. Zdrowiu 2021, 6, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawęda, A.; Kamińska, J.; Wawoczna, G.; Tobor, E.; Ogonowska, D. Ból Pooperacyjny w Opinii Pacjenta. Piel. Pol. 2020, 78, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morone, N.E.; Weiner, D.K. Pain as the Fifth Vital Sign: Exposing the Vital Need for Pain Education. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 1728–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. APS1995 Presidential Address. Pain Forum 1996, 5, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobbezoo, F.; Ahlberg, J.; Raphael, K.G.; Wetselaar, P.; Glaros, A.G.; Kato, T.; Santiago, V.; Winocur, E.; De Laat, A.; De Leeuw, R.; et al. International Consensus on the Assessment of Bruxism: Report of a Work in Progress. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrbach, R.; Bair, E.; Fillingim, R.B.; Gonzalez, Y.; Gordon, S.M.; Lim, P.-F.; Ribeiro-Dasilva, M.; Diatchenko, L.; Dubner, R.; Greenspan, J.D.; et al. Clinical Orofacial Characteristics Associated with Risk of First-Onset TMD: The OPPERA Prospective Cohort Study. J. Pain 2013, 14, T33–T50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michelotti, A.; Cioffi, I.; Festa, P.; Scala, G.; Farella, M. Oral Parafunctions as Risk Factors for Diagnostic TMD Subgroups. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioffi, I.; Landino, D.; Donnarumma, V.; Castroflorio, T.; Lobbezoo, F.; Michelotti, A. Frequency of Daytime Tooth Clenching Episodes in Individuals Affected by Masticatory Muscle Pain and Pain-Free Controls during Standardized Ability Tasks. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dworkin, S.F.; LeResche, L. Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders: Review, Criteria, Examinations and Specifications, Critique. J. Craniomandib. Disord. 1992, 6, 301–355. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman, E.; Ohrbach, R.; Truelove, E.; Look, J.; Anderson, G.; Goulet, J.-P.; List, T.; Svensson, P.; Gonzalez, Y.; Lobbezoo, F.; et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014, 28, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstka, A.A.; Kozowska, L.; Kijak, K.; Brzózka, M.; Gronwald, H.; Skomro, P.; Lietz-Kijak, D. Accurate Diagnosis and Treatment of Painful Temporomandibular Disorders: A Literature Review Supplemented by Own Clinical Experience. Pain Res. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1002235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Cai, J.; Yu, Y.; Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Wu, M. Therapeutic Agents for the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders: Progress and Perspective. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 596099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadden, S.W. Orofacial Pain. Guidelines for Assessment, Diagnosis, and Management, 4th Edition (2008). Eur. J. Orthod. 2009, 31, 216–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelotti, A.; Iodice, G. The Role of Orthodontics in Temporomandibular Disorders. J. Oral Rehabil. 2010, 37, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczyńska-Dragon, K.; Fiegler-Rudol, J.; Baron, S.; Nitecka-Buchta, A. Expanding the therapeutic profile of topical cannabidiol in temporomandibular disorders: Effects on sleep quality and migraine disability in patients with bruxism-associated muscle pain. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczyńska-Dragon, K.; Kurek-Górecka, A.; Niemczyk, W.; Nowak, Z.; Baron, S.; Olczyk, P.; Nitecka-Buchta, A.; Kempa, W.M. Cannabidiol Intervention for Muscular Tension, Pain, and Sleep Bruxism Intensity—A Randomized, Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitecka-Buchta, A.; Nowak-Wachol, A.; Wachol, K.; Walczyńska-Dragon, K.; Olczyk, P.; Batoryna, O.; Kempa, W.; Baron, S. Myorelaxant Effect of Transdermal Cannabidiol Application in Patients with TMD: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Aswath, N. Comparative Efficacy of Analgesic Gel Phonophoresis and Ultrasound in the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2019, 30, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.K.; Fillingim, R.B.; Lee, S.; Brao, R.; Price, D.D.; Neubert, J.K. Effects of High-Dose Capsaicin on TMD Subjects: A Randomized Clinical Study. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2017, 2, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitecka-Buchta, A.; Buchta, P.; Tabeńska-Bosakowska, E.; Walczyńska-Dragoń, K.; Baron, S. Myorelaxant Effect of Bee Venom Topical Skin Application in Patients with RDC/TMD Ia and RDC/TMD Ib: A Randomized, Double Blinded Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 296053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.C.F.; Wong, R.W.K.; Rabie, A.B.M. Clinical Effect of a Topical Herbal Ointment on Pain in Temporomandibular Disorders: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, S.L.; Mehta, N.; Forgione, A.G.; Melis, M.; Al-Badawi, E.; Ceneviz, C.; Zawawi, K.H. Use of Theraflex-TMJ Topical Cream for the Treatment of Temporomandibular Joint and Muscle Pain. CRANIO® 2004, 22, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winocur, E.; Gavish, A.; Halachmi, M.; Eli, I.; Gazit, E. Topical Application of Capsaicin for the Treatment of Localized Pain in the Temporomandibular Joint Area. J. Orofac. Pain 2000, 14, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, S.-M.; Choi, J.-K. Effect of Indomethacin Phonophoresis on the Relief of Temporomandibular Joint Pain. CRANIO® 1997, 15, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V. Cox Selective Antiinflammatory Drugs And Its Development. IJPDA Int. J. Pharm. Drug Anal. 2015, 3, 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, R.W.; Melmed, G.Y.; Henning, J.M.; Bernal, M. Risk of Upper Gastrointestinal Injury and Events in Patients Treated With Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1/COX-2 Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs), COX-2 Selective NSAIDs, and Gastroprotective Cotherapy: An Appraisal of the Literature. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2004, 10, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grlic, L. A Comparative Study on Some Chemical and Biological Characteristics of Various Samples of Cannabis Resin. Bull. Narc. 1962, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Amar, M. Cannabinoids in Medicine: A Review of Their Therapeutic Potential. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 105, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izzo, A.A.; Borrelli, F.; Capasso, R.; Di Marzo, V.; Mechoulam, R. Non-Psychotropic Plant Cannabinoids: New Therapeutic Opportunities from an Ancient Herb. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 515–527, Erratum in Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2009, 30, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione, S.; Costa, B.; Di Marzo, V. Endocannabinoids: A Unique Opportunity to Develop Multitarget Analgesics. Pain 2013, 154, S87–S93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G. Pharmacological Actions of Cannabinoids. In Cannabinoids; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, H.T.; O’Brien, M.; McDougall, J.J. Attenuation of Early Phase Inflammation by Cannabidiol Prevents Pain and Nerve Damage in Rat Osteoarthritis. Pain 2017, 158, 2442–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, K.S.; Milewski, M.; Swadley, C.L.; Brogden, N.K.; Ghosh, P.; Stinchcomb, A.L. Challenges and Opportunities in Dermal/Transdermal Delivery. Ther. Deliv. 2010, 1, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodzki, M.; Godin, B.; Rakou, L.; Mechoulam, R.; Gallily, R.; Touitou, E. Cannabidiol-Transdermal Delivery and Anti-Inflammatory Effect in a Murine Model. J. Control. Release 2003, 93, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastina, J.T.; Abel, M.G.; Bollinger, L.M.; Best, S.A. Topical Cannabidiol Application May Not Attenuate Muscle Soreness or Improve Performance: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2025, 10, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariati, H. Decreasing of Pain Scale Through Warm Compress Among Elderly with Rheumatoid Arthritis. JPKM J. Penelit. Keperawatan Med. 2021, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haile, G.; Hailemariam, T.T.; Haile, T.G. Effectiveness of Ultrasound Therapy on the Management of Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. JPR J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1251–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiyer, R.; Noori, S.A.; Chang, K.-V.; Jung, B.; Rasheed, A.; Bansal, N.; Ottestad, E.; Gulati, A. Therapeutic Ultrasound for Chronic Pain Management in Joints: A Systematic Review. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 1437–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.; Butterworth, C.; Lowe, D.; Rogers, S.N. Factors Associated with Restricted Mouth Opening and Its Relationship to Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients Attending a Maxillofacial Oncology Clinic. Oral Oncol. 2008, 44, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasotra, R. Effectiveness of Physiotherapy Intervention on Trismus (Lock–Jaw): A Case Report. IJHS Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, A.; Wenneberg, B.; Mejersjö, C. Reported Opening Limitations as a TMD Symptom: A Clinical Report on Diagnoses and Outcome. Clin. Surg. 2017, 2, 1572. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsoulis, P.; Marini, A.; Iliou, K.; Galani, V.; Zimpis, A.; Kanavaros, P.; Paraskevas, G. Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders Related to the Degree of Mouth Opening and Hearing Loss. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2011, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Anese, A.P.; Schultz, K.; Ribeiro, K.; Angelis, E.C. Early and Long-Term Effects of Physiotherapy for Trismus in Patients Treated for Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer. Appl. Cancer Res. 2010, 30, 335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Derry, S.; Moore, R.A.; Gaskell, H.; McIntyre, M.; Wiffen, P.J. Topical NSAIDs for Acute Musculoskeletal Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2019, CD007402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derry, S.; Conaghan, P.; Da Silva, J.A.P.; Wiffen, P.J.; Moore, R.A. Topical NSAIDs for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2020, CD007400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisawa, T.; Nakajima, A.; Haida, H.; Wakita, R.; Ando, S.; Yoshioka, T.; Ikoma, T.; Tanaka, J.; Fukayama, H. Evaluation of Calcium Alginate Gel as Electrode Material for Alternating Current Iontophoresis of Lidocaine Using Excised Rat Skin. J. Med. Dent. Sci. 2014, 61, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Karpiński, T.M. Selected Medicines Used in Iontophoresis. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhote, V.; Bhatnagar, P.; Mishra, P.K.; Mahajan, S.C.; Mishra, D.K. Iontophoresis: A Potential Emergence of a Transdermal Drug Delivery System. Sci. Pharm. 2012, 80, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straburzyńska-Lupa, A.; Straburzyński, G. Fizjoterapia; PZWL: Warszawa, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, J.; Du, L.; Li, M.; Liu, B.; Zhu, W.; Jin, Y. Transdermal Enhancement Effect and Mechanism of Iontophoresis for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 466, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cal, K.; Stefanowska, J. Metody Zwiększania Przenikania Substancji Leczniczych Przez Skórę. Farm. Pol. 2010, 66, 514–520. [Google Scholar]

- Berti, J.J.; Lipsky, J.J. Transcutaneous Drug Delivery: A Practical Review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1995, 70, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.; McCarron, P.; Woolfson, A.D.; Donnelly, R. Innovative Strategies for Enhancing Topical and Transdermal Drug Delivery. Open Drug Deliv. J. 2007, 107, 36–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Da, D.D. Prodrug Strategies for Enhancing the Percutaneous Absorption of Drugs. Molecules 2014, 19, 20780–20807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadon, D.; McCrudden, M.T.C.; Courtenay, A.J.; Donnelly, R.F. Enhancement Strategies for Transdermal Drug Delivery Systems: Current Trends and Applications. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2022, 12, 758–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sharma, U.S. Liposomes in Drug Delivery: Progress and Limitations. Int. J. Pharm. 1997, 154, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cal, K. Across Skin Barrier: Known Methods, New Performances. Front. Drug Des. Discov. 2009, 4, 162–188. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, H.A.E. Transdermal Drug Delivery: Penetration Enhancement Techniques. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2005, 2, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svensson, P.; Houe, L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Effect of systemic versus topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on postexercise jaw-muscle soreness: A placebo-controlled study. J. Orofac. Pain 1997, 11, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Di Rienzo Businco, L.; Di Rienzo Businco, A.; D’Emilia, M.; Lauriello, M.; Coen Tirelli, G. Topical versus systemic diclofenac in the treatment of temporomandibular joint dysfunction symptoms. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2004, 24, 279–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg, E.C.; Kopp, S.; Akerman, S. Diclofenac sodium as an alternative treatment of temporomandibular joint pain. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1996, 54, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, I.; Chahal, A.; Kapoor, G.; Chaudhuri, P.; Alghadir, A.H.; Khan, M.; Kashoo, F.Z.; Esht, V.; Alshehri, M.M.; Shaphe, M.A.; et al. Effects of a program consisting of strain/counterstrain technique, phonophoresis, heat therapy, and stretching in patients with temporomandibular joint dysfunction. Medicine 2023, 102, e34569, Erratum published in: Medicine 2023, 102, e36940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Tsukimura, N.; Ishizuka, T.; Kohinata, K.; Yonehara, Y.; Honda, K. Local application of Aqua Titan improves symptoms of temporomandibular joint muscle disorder: A preliminary study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 483–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zuheri, I.; Persson, G. The Effect of Topical Anesthesia on Jaw Pain Thresholds in Patients with Generalized Pain. Ph.D. Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2014. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-97863 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Jerner, A.; Svedberg, L. The Effect of Topical Anesthesia on Pain Perception in Patients with Local Myalgia. Ph.D. Thesis, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden, 2014. Available online: https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-97853 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Schiffman, E.L.; Braun, B.L.; Lindgren, B.R. Temporomandibular joint iontophoresis: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J. Orofac. Pain 1996, 10, 157–165. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Y.M.; Ferreira, D.M.A.O.; Conti, P.C.R.; Baad-Hansen, L.; Svensson, P.; Bonjardim, L.R. Topical anaesthesia degree is reduced in temporomandibular disorders patients: A novel approach to assess underlying mechanisms of the somatosensory alterations. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria for Inclusion | Criteria for Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | Temporomandibular disorders | Cadaver and animal studies |

| Intervention | Local percutaneous or per-mucosal drug delivery to the masticatory system | Muscle punctures or any systemic intervention |

| Control | Any | None |

| Outcomes | Health-related quality of life, temporomandibular region pain, mandibular abduction | Non-quantifiable results |

| Timeframe | No limit | Not applicable |

| Settings | Randomized controlled trials | Preprints, non-English reports |

| First Author, Publication Year | Entire Sample (n) | Diagnosis | Target Structure | Delivery Method | Control Group (n0) | Control Group Active Substance | Study Groups (n1, n2, etc.) | Study Active Substances |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walczyńska-Dragon K, 2024 [33] | 40 | Sleep bruxism and TMD | Masseter intraorally | Topical mucous application | 20 | Placebo formulation | 20 | 5% and 10% cannabidiol formulations |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2019 [34] | 60 | Myofascial pain | Masseter | Topical skin application | 30 | Placebo ointment | 30 | 1.46% cannabidiol |

| Ramakrishnan SN, 2019 [35] | 50 | TMJ pain | TMJ | Phonophoresis | 25 | Plain ultrasound | 25 | Aceclofenac gel |

| Campbell BK, 2017 [36] | 15 | TMD, TMJ pain | TMJ and masseter | Topical skin application | 8 | Placebo cream | 7 | 8% capsaicin topical emollient cream base |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2014 [37] | 68 | Myofascial pain | Masseter | Topical skin application | 34 | Placebo ointment (vaseline) | 34 | 0.0005% bee venom ointment |

| Li LC, 2009 [38] | 55 | Myalgia and/or TMJ pain | Masseter/Temporalis muscle/TMJ | Topical skin application | 27 | Placebo (vaseline) | 28 | Ping-On ointment |

| Lobo SL, 2004 [39] | 52 | Myalgia and/or TMJ pain | Masseter/TMJ | Topical skin application | 26 | Placebo cream | 26 | Theraflex-TMJ topical cream |

| Winocur E, 2000 [40] | 30 | Myalgia and/or TMJ pain | Masseter/Temporalis muscle/TMJ | Topical skin application | 13 | Placebo cream | 17 | 0.025% capsaicin cream |

| Shin SM, 1997 [41] | 20 | TMJ pain | TMJ | Phonophoresis | 10 | Placebo gel | 10 | 1% indomethacin gel |

| First Author, Publication Year | Patient Group | Data Type | Baseline Value | 2 Days | 7 Days | 10 Days | 14 Days | 15 Days | 20 Days | 21 Days | 28 Days | 30 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walczyńska-Dragon K, 2024 [33] | Cannabidiol 5% | Value | 6.00 | 4.50 | 3.50 | |||||||

| Cannabidiol 10% | Value | 6.00 | 4.00 | 2.00 | ||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 6.00 | 5.00 | 5.50 | ||||||||

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2019 [34] | Cannabidiol 1.46% | Value | 5.60 | 1.67 | ||||||||

| SD | 1.38 | 1.44 | ||||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 5.10 | 4.60 | |||||||||

| SD | 1.26 | 1.58 | ||||||||||

| Ramakrishnan SN, 2019 [35] | Aceclofenac | Value | 6.40 | 2.12 | ||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 4.68 | 2.06 | |||||||||

| Campbell BK, 2017 [36] | 8% capsaicin topical emollient cream base | Value | 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.95 | |||||||

| Placebo | Value | 3.7 | 3.2 | 2.0 | ||||||||

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2014 [37] | Bee venom | Value | 6.00 | 2.00 | ||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 5.00 | 4.00 | |||||||||

| Li LC, 2009 [38] | Ping-On | Value | 4.94 | 4.25 | 3.15 | 2.51 | 2.19 | |||||

| SD | 1.44 | 1.45 | 1.63 | 1.73 | 1.81 | |||||||

| Placebo | Value | 4.78 | 4.69 | 4.48 | 4.26 | 4.08 | ||||||

| SD | 1.19 | 1.31 | 1.24 | 1.28 | 1.44 | |||||||

| Lobo SL, 2004 [39] | Theraflex | Value | 5.09 | 2.55 | 2.11 | 3.11 | ||||||

| SD | 2.44 | 2.40 | 2.14 | 2.76 | ||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 4.25 | 3.70 | 3.66 | 3.71 | |||||||

| SD | 2.20 | 2.27 | 1.88 | 1.88 | ||||||||

| Winocur E, 2000 [40] | Capsaicin cream | Value | 7.25 | 3.39 | ||||||||

| SD | 1.0 | 2.62 | ||||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 6.65 | 4.00 | |||||||||

| SD | 2.32 | 2.50 | ||||||||||

| Shin SM, 1997 [41] | Indomethacin | Value | 6.03 | 4.64 | ||||||||

| SD | 1.49 | 1.21 | ||||||||||

| Placebo | Value | 4.96 | 4.35 | |||||||||

| SD | 1.79 | 1.48 |

| First Author, Publication Year | Patient Group | Data Type | Baseline Value | 28 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li LC, 2009 [38] | Ping-On | Value | 31.38 | 35.91 |

| SD | 11.46 | 11.45 | ||

| Placebo | Value | 33.18 | 34.00 | |

| SD | 12.39 | 12.07 | ||

| Winocur E, 2000 [40] | 0.025% capsaicin | Value | 38.2 | 39.2 |

| SD | 8.1 | 8.5 | ||

| Placebo | Value | 43.2 | 46.2 | |

| SD | 8.4 | 10.4 |

| Author (Year) | Active Substance | Data on Adverse Reactions |

|---|---|---|

| Walczyńska-Dragon K, 2024 [33] | Cannabidiol | No adverse events reported. |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2019 [34] | Cannabidiol | No adverse reactions reported. No psychoactive side effects observed. |

| Ramakrishnan SN, 2019 [35] | Aceklofenac | No adverse reactions reported. |

| Campbell BK, 2017 [36] | Capsaicin | Pain: 1 patient in the experimental group and 1 non-TMD patient in an arm not included in this systematic review requested that the cream be removed due to excessive pain. |

| Nitecka-Buchta A, 2014 [37] | Bee venom | Allergic reactions: 4 people were excluded at the recruitment stage—1 in the experimental group and 3 in the control group. Risk of swelling, itching, and redness. |

| Li LC, 2009 [38] | Ping-On ointment | Eye irritation: 6 patients in the experimental group. Itching: 1 patient in the placebo group and 1 in the experimental group. Skin burning sensation: 1 patient discontinued treatment for 3 days. Adverse effects were mild in severity. |

| Lobo SL, 2004 [39] | Theraflex | Skin irritation and/or burning at the application site: observed in 2 patients in the experimental group and 2 in the placebo group. |

| Winocur E, 2000 [40] | Capsaicin | Heat sensation, burning sensation, and/or localized redness: 13 of the 15 patients reported mild to moderate symptoms; 2 patients discontinued due to an “unbearable” burning sensation; 2 patients in the placebo group reported a mild warm sensation and redness at the application site. |

| Shin SM, 1997 [41] | Indomethacin | No adverse reactions reported. |

| Substance Tested | Number of Studies | Number of Patients | Control Group | SD in Control Group | Study Group | SD in Study Group | Mean Difference | Standard Error | Lower 95% Confidence Interval | Upper 95% Confidence Interval | Significance Level | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aceclofenac | 1 | 50 | 2.06 | - | 2.12 | - | 0.06 | - | - | - | - | Some concerns |

| Bee venom | 1 | 68 | 4.00 | - | 2.00 | - | −2.00 | - | - | - | - | Low |

| Cannabidiol 1.46% | 1 | 60 (30/30) | 4.60 | 1.58 | 1.67 | 1.44 | −2.93 | 0.39 | −3.71 | −2.15 | <0.0001 | Low |

| Cannabidiol 5% | 1 | 40 | 5.00 | - | 4.50 | - | −0.50 | - | - | - | - | Low |

| Cannabidiol 10% | 1 | 40 | 5.00 | - | 4.00 | - | −1.00 | - | - | - | - | Low |

| Ping-On | 1 | 55 (28/27) | 4.48 | 1.24 | 3.15 | 1.63 | −1.33 | 0.39 | −2.11 | −0.55 | 0.0012 | Low |

| Theraflex | 1 | 52 (26/26) | 3.66 | 1.88 | 2.11 | 2.14 | −1.55 | 0.56 | −2.67 | −0.43 | 0.0078 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galant, K.; Romańczyk, K.; Chęciński, M.; Chęcińska, K.; Turosz, N.; Rąpalska, I.; Hoppe, A.; Jakubowska, A.; Chlubek, D.; Sikora, M. Percutaneous Drug Delivery to the Masticatory System: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123110

Galant K, Romańczyk K, Chęciński M, Chęcińska K, Turosz N, Rąpalska I, Hoppe A, Jakubowska A, Chlubek D, Sikora M. Percutaneous Drug Delivery to the Masticatory System: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123110

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalant, Kacper, Kalina Romańczyk, Maciej Chęciński, Kamila Chęcińska, Natalia Turosz, Iwona Rąpalska, Amelia Hoppe, Alicja Jakubowska, Dariusz Chlubek, and Maciej Sikora. 2025. "Percutaneous Drug Delivery to the Masticatory System: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123110

APA StyleGalant, K., Romańczyk, K., Chęciński, M., Chęcińska, K., Turosz, N., Rąpalska, I., Hoppe, A., Jakubowska, A., Chlubek, D., & Sikora, M. (2025). Percutaneous Drug Delivery to the Masticatory System: A Systematic Review and Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3110. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123110