Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Oral and Maxillofacial Status in Patients Undergoing Antiresorptive Therapy and Its Relationship with MRONJ

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Evaluation

2.2. Implementing Preventive and/or Therapeutic Measures

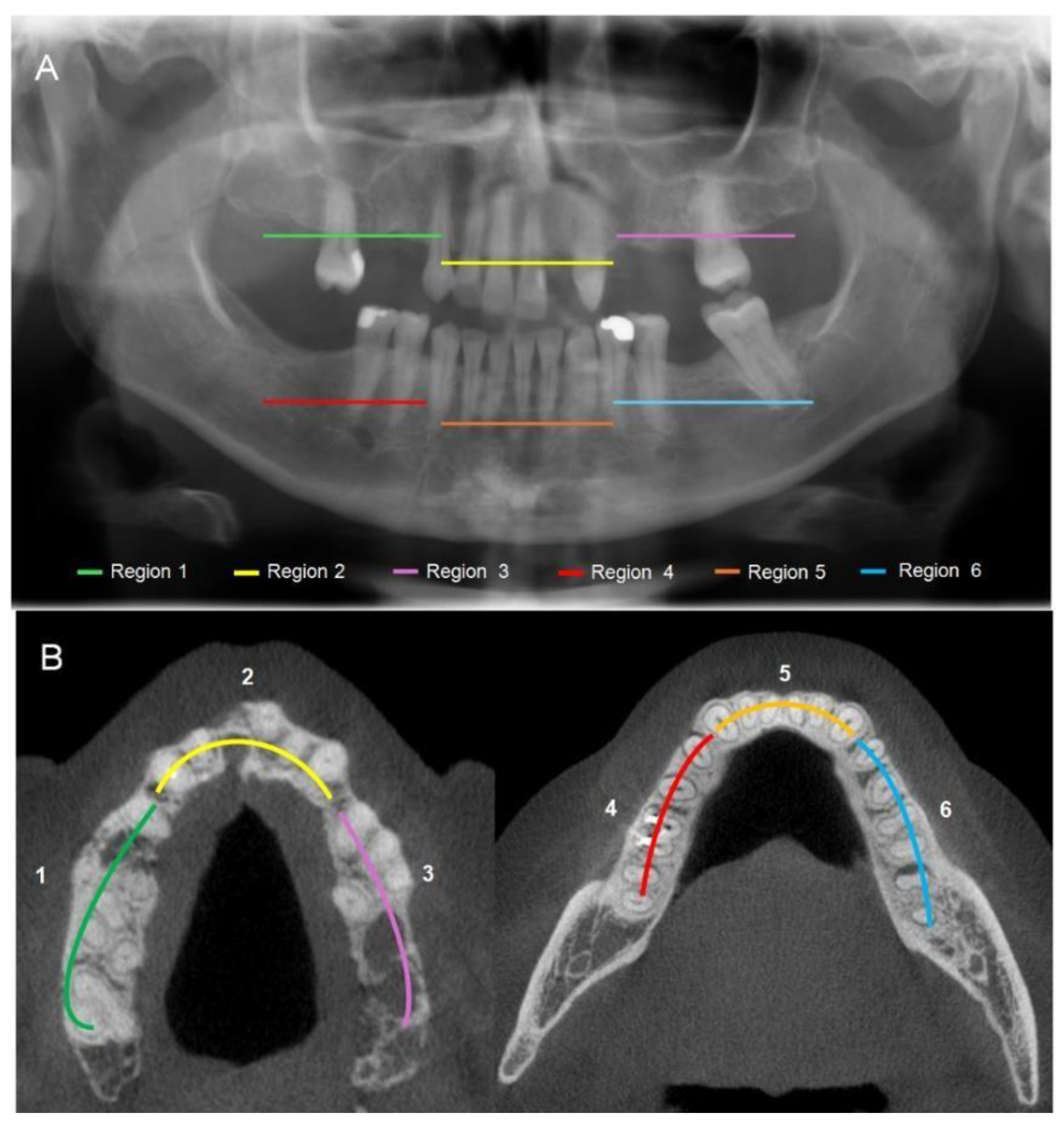

2.3. Imaging Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

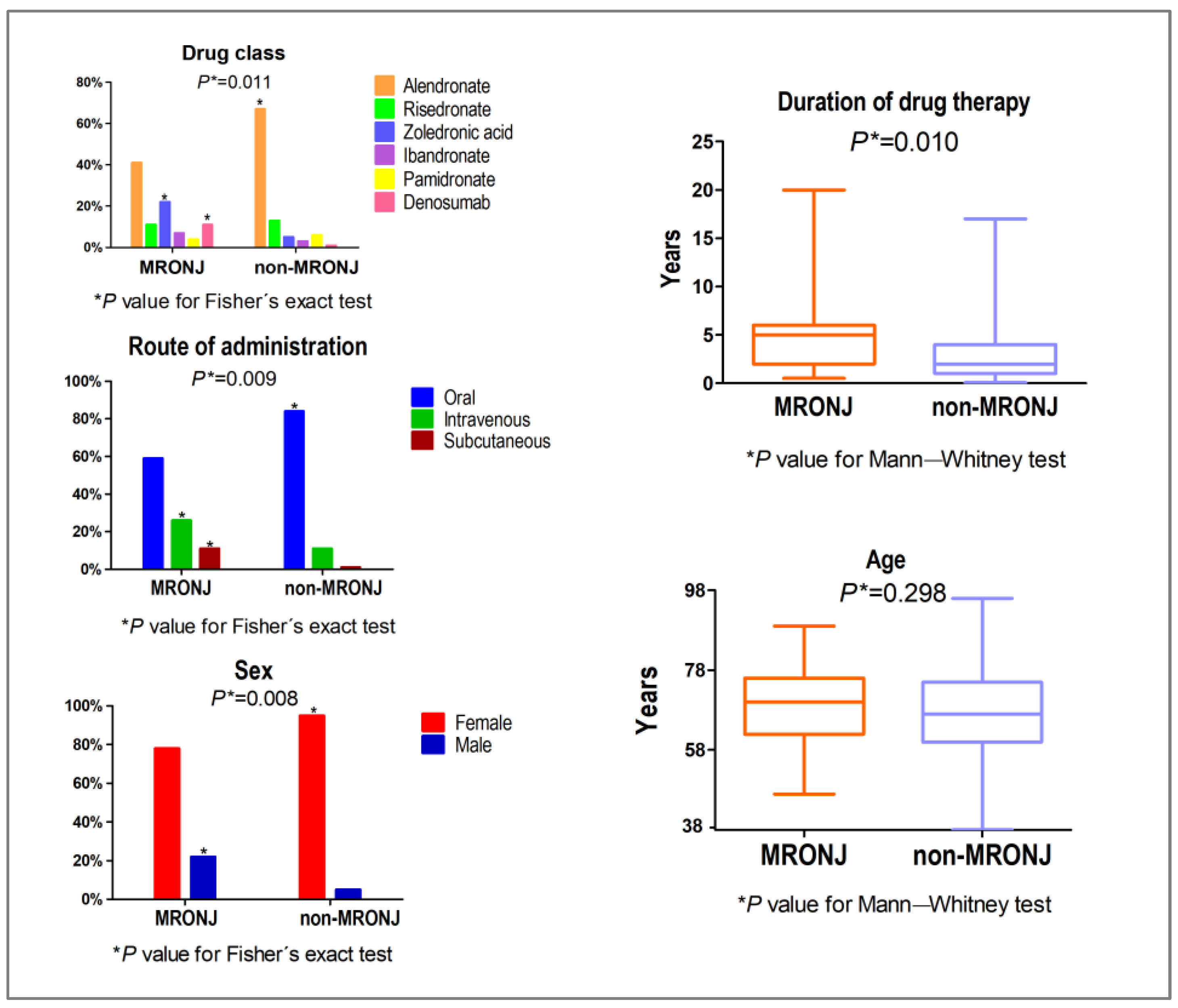

3.1. Demographic Data

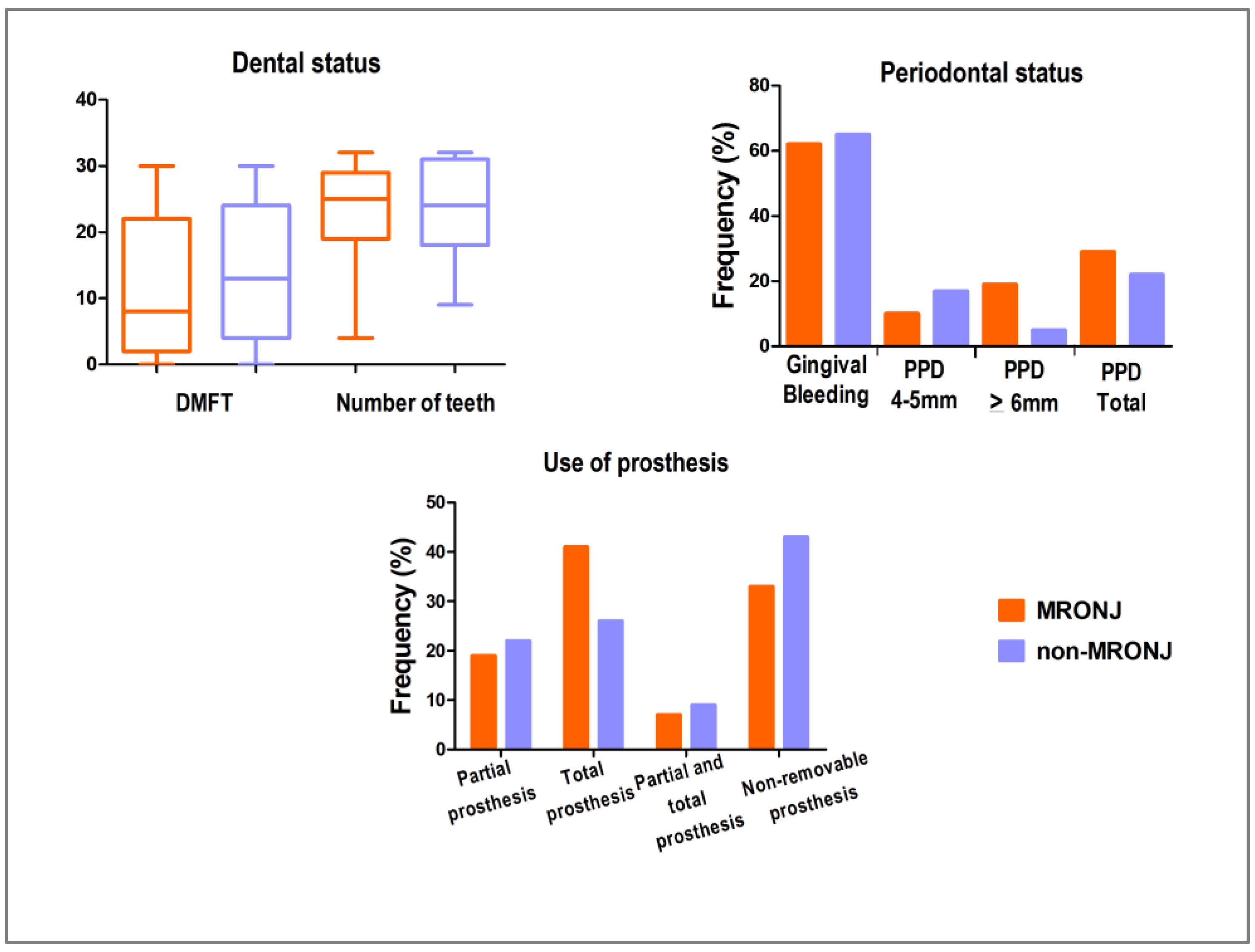

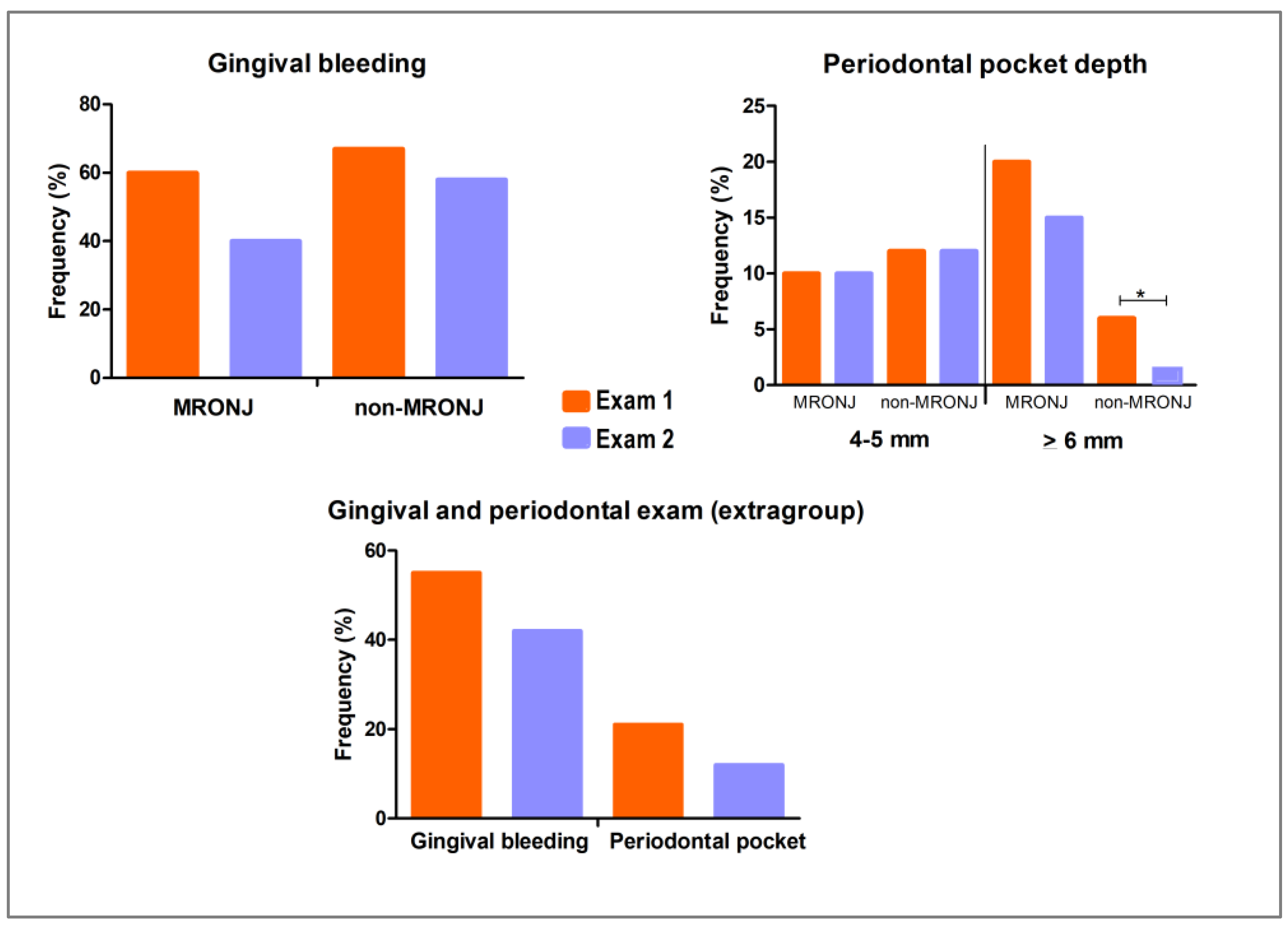

3.2. Clinical Analysis

3.2.1. Dental Status

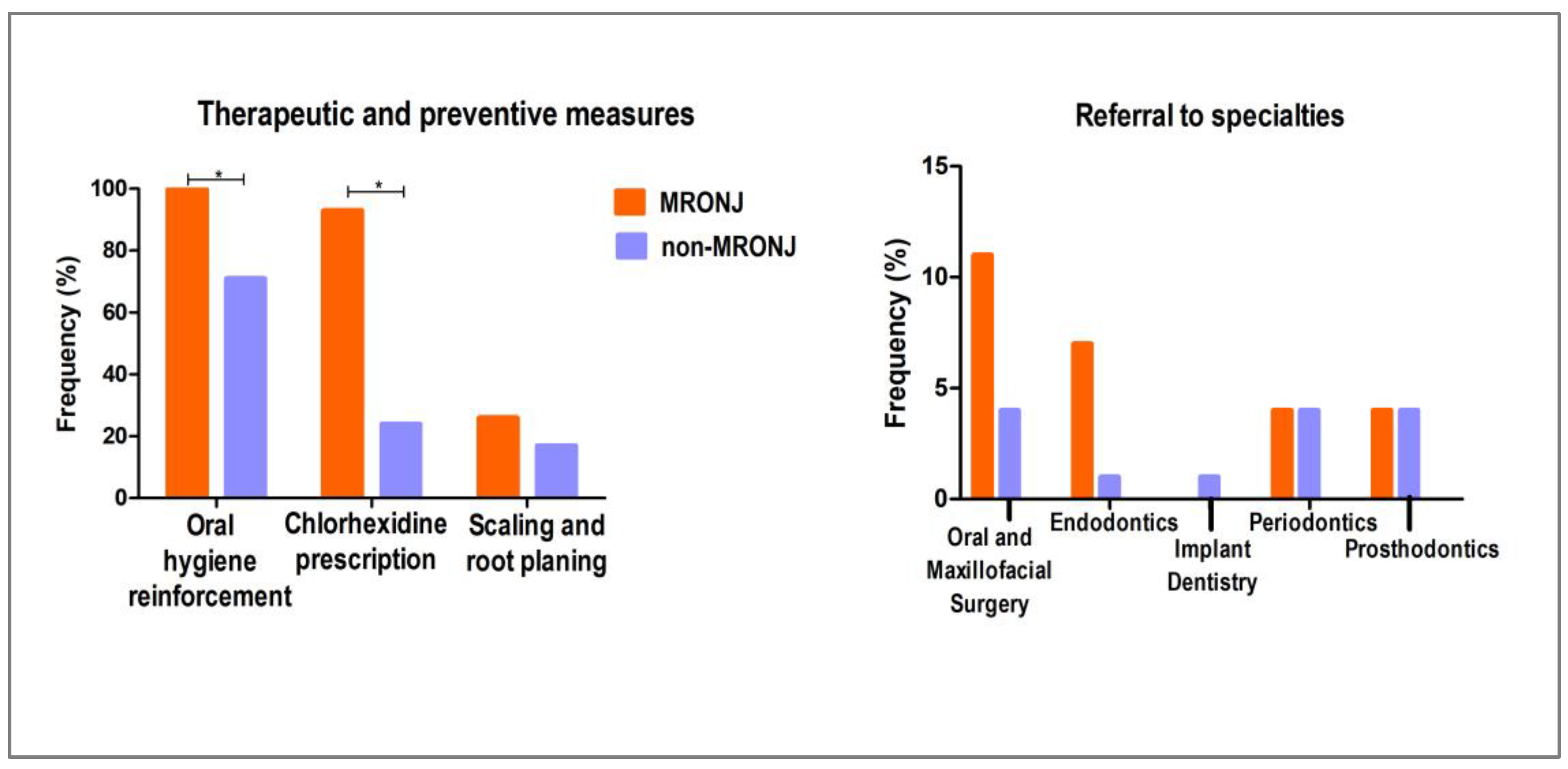

3.2.2. Therapeutic and Preventive Measures

3.2.3. Clinical Re-Evaluation After Implementing Preventive and Therapeutic Measures

3.3. Imaging Analysis

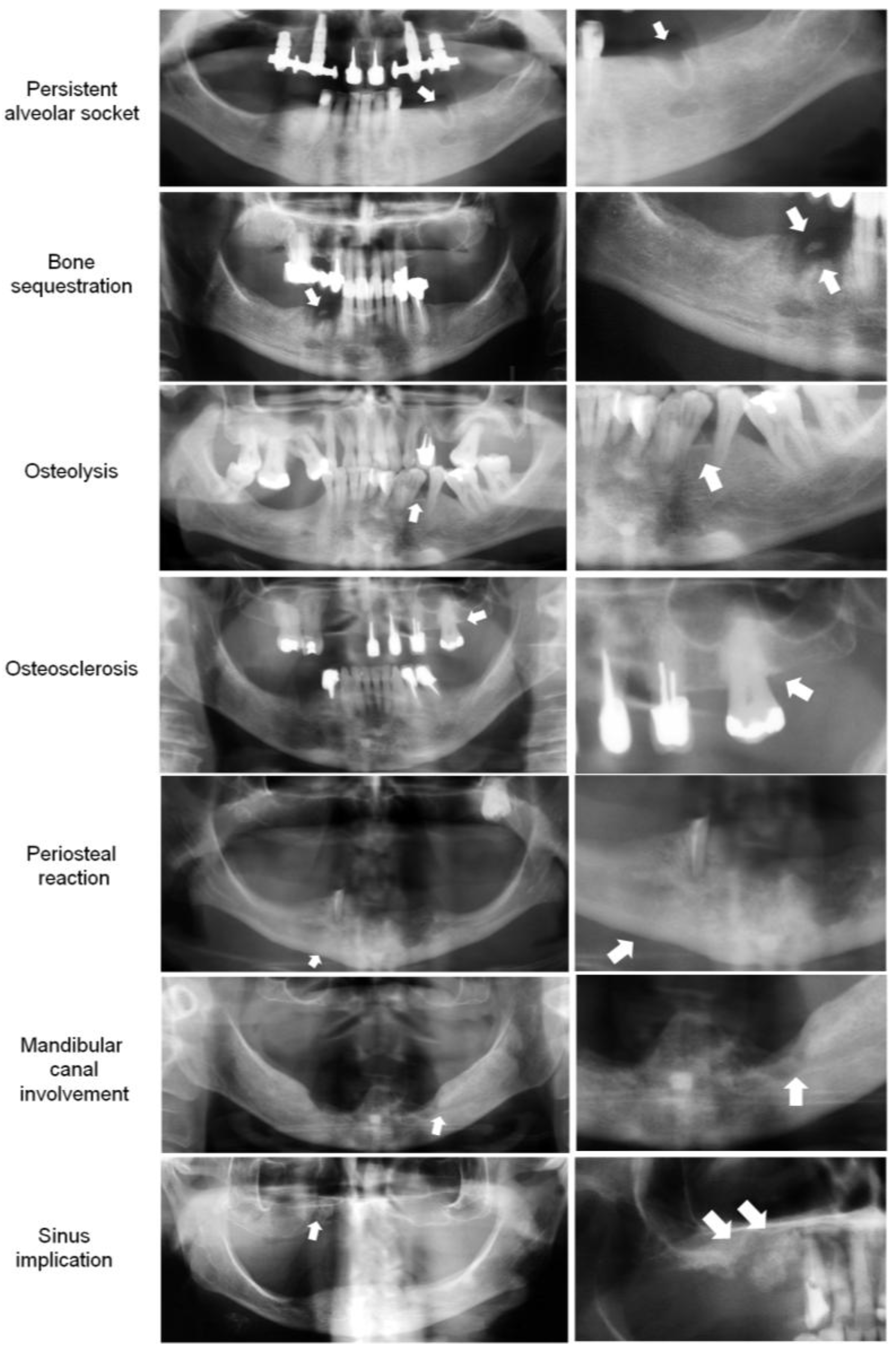

3.3.1. Bone Features on Panoramic Radiography (PAN)

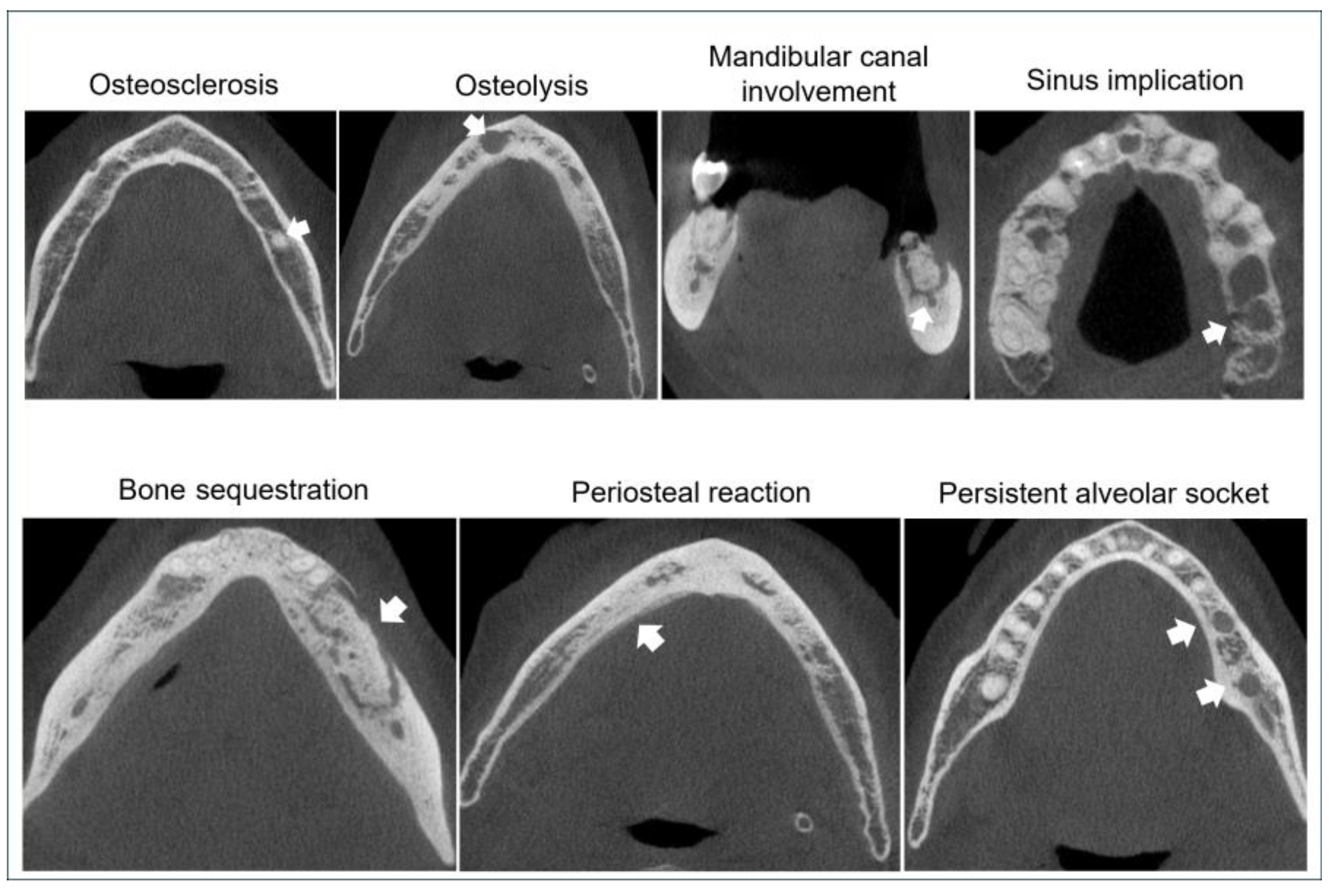

3.3.2. Bone Features on Cone Beam Computerized Tomography (CBCT)

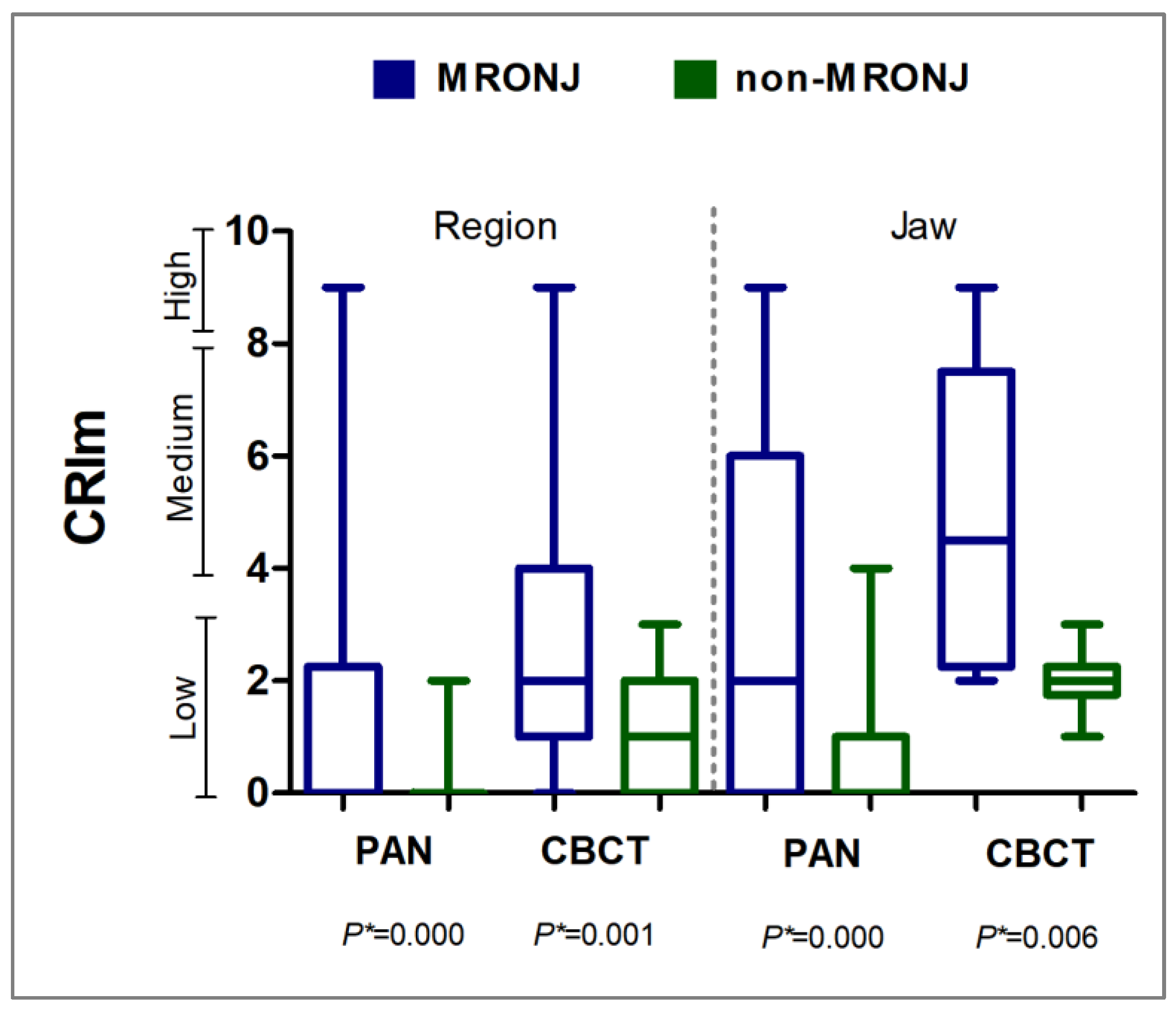

3.3.3. Composite Radiographic Index Modified (CRIm)

Panoramic Radiography (PAN) and Cone Beam Computerized Tomography (CBCT)

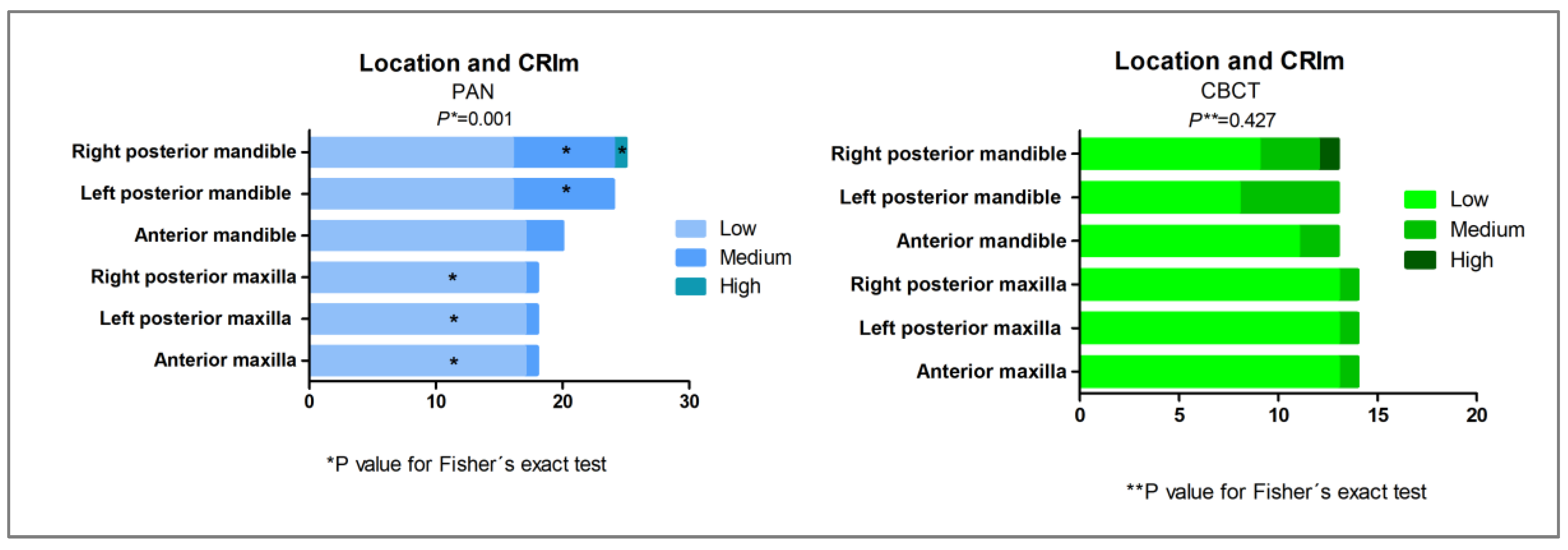

3.3.4. CRIm Distribution According to Anatomical Region

3.3.5. AAOMS Staging

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AAOMS | American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons |

| CBCT | cone beam computerized tomography |

| CPI | community periodontal index |

| CPIm | community periodontal index modified |

| CRI | composite radiographic index |

| CRIm | composite radiographic index modified |

| CTX | C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide |

| DMFT | decayed, missing, and filled teeth |

| MRONJ | medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw |

References

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws—2022 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Cassia Tornier, S.; Macedo, F.J.; Sassi, L.M.; Schussel, J.L. Quality of life in cancer patients with or without medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 6713–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.J.; Kim, M.J.; Ahn, K.M. Associated systemic diseases and etiologies of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A retrospective study of 265 surgical cases. Maxillofac. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2023, 45, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oçal, M.Ç.; Baybars, S.C.; Duran, M.H. MRONJ with current diagnostic and treatment approaches. Akd Tıp Derg. 2024, 10, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneda, T.; Hagino, H.; Sugimoto, T.; Ohta, H.; Takahashi, S.; Soen, S.; Taguchi, A.; Nagata, T.; Urade, M.; Shibahara, T.; et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position Paper 2017 of the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J. Bone Miner Metab. 2017, 35, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Fantasia, J.; Goodday, R.; Aghaloo, T.; Mehrotra, B.; O’Ryan, F. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw—2014 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1938–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarelis, H.; Shah, N.P.; Dhariwal, D.K.; Pazianas, M. Infection and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-H.; Kim, S.-G. Unveiling medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A rapid review of etiology, drug holidays, and treatment strategies. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedogni, A.; Fusco, V.; Di Fede, O.; Bettini, G.; Panzarella, V.; Mauceri, R.; Saia, G.; Campisi, G. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongratwanich, P.; Shimabukuro, K.; Konishi, M.; Nagasaki, T.; Ohtsuka, M.; Suei, Y.; Nakamoto, T.; Verdonschot, R.G.; Kanesaki, T.; Sutthiprapaporn, P.; et al. Do various imaging modalities provide potential early detection and diagnosis of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw? A review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2021, 50, 20200417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.Y.; Yang, W.F.; Leung, Y.Y. The Role of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) in the Diagnosis and Clinical Management of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ). Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rabié, C.; Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Oliveira-Santos, C.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R. Early imaging signs of the use of antiresorptive medication and MRONJ: A systematic review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 2973–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, M.; O’Ryan, F.; Chavez, V.; Lathon, P.V.; Sanchez, G.; Hatcher, D.C.; Indresano, A.T.; Lo, J.C. Radiographic findings in bisphosphonate-treated patients with stage 0 disease in the absence of bone exposure. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 2232–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, K.; Grogan, T.R.; Eshaghzadeh, E.; Hadaya, D.; Elashoff, D.A.; Aghaloo, T.L.; Tetradis, S. Medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw in osteoporotic vs oncologic patients-quantifying radiographic appearance and relationship to clinical findings. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2019, 48, 20180128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfanti, Z.; Tetradis, S.; Nikitakis, N.G.; Alexiou, K.E.; Makris, N.; Angelopoulos, C.; Tsiklakis, K. Radiologic findings of osteonecrosis, osteoradionecrosis, osteomyelitis and jaw metastatic disease with cone beam CT. Eur. J. Radiol. 2023, 165, 110916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.E.; Yoo, S.; Choi, S.C. Several issues regarding the diagnostic imaging of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Imaging Sci. Dent. 2020, 50, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Rabié, C.; Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Ferreira-Leite, A.; Coucke, W.; Gielen, E.; Van den Wyngaert, T.; Jacobs, R. Local radiographic risk factors for MRONJ in osteoporotic patients undergoing tooth extraction. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 1632–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawawda, O.; Urvasızoğlu, G.; Akhmedova, L.; Karadağ, Ö. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Risk factors, management and prevention in dental practices. New Trends Med. Sci. 2025, 6, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauceri, R.; Coniglio, R.; Abbinante, A.; Carcieri, P.; Tomassi, D.; Panzarella, V.; Di Fede, O.; Bertoldo, F.; Fusco, V.; Bedogni, A.; et al. The preventive care of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ): A position paper by Italian experts for dental hygienists. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 6429–6440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaico, G.; Casu, C. Management and maintenance of oral health: Personalized primary prevention strategies and protocols in patients at risk of developing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. INNOSC Theranostics Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 7, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaêta-Araujo, H.; Ferreira Leite, A.; de Faria Vasconcelos, K.; Coropciuc, R.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R.; Oliveira-Santos, C. Why do some extraction sites develop medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw and others do not? A within-patient study assessing radiographic predictors. Int. J. Oral Implantol. 2021, 14, 87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, L.; Liu, D.; Wu, F.; Wang, M.; Cen, Y.; Ma, L. Correlation between bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in patients undergoing long-term anti-osteoporosis treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.Z.; Padilla, R.J.; Reside, G.J.; Tyndall, D.A. Comparing panoramic radiographs and cone beam computed tomography: Impact on radiographic features and differential diagnoses. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2018, 126, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, A.; Pekiner, F.N. Radiographic findings of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Comparison with cone-beam computed tomography and panoramic radiography. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajappa, A.K.; Dwivedi, N.; Tiwari, R. Artifacts: The downturn of CBCT image. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2015, 5, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünsal, G.; Orhan, K. What do we expect to visualize on the radiographs of MRONJ patients? J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2021, 38, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.R.; Chen, C.S.; Leroux, B.G.; Lee, P.P.; Hollender, L.G.; Santos, E.C.; Drew, S.P.; Hung, K.C.; Schubert, M.M. Mandibular cortical bone evaluation on cone beam computed tomography images of patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 113, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, M.A.; Thang, T.; Krishnamoorthy, G. Using thickened lamina dura as a predictor of developing medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ). Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2025, 139, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MRONJ | Non-MRONJ | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | (n = 102) | (n = 558) | (n = 660) | p * | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sclerotic trabecular bone pattern | 102 | 100 | 558 | 100 | 660 | 100 | - |

| Lamina dura thickening | 42 | 42 | 202 | 36 | 244 | 37 | 0.372 |

| Osteolysis | 37 | 36 | 47 | 8 | 84 | 13 | 0.000 |

| Bone sequestration | 16 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Mandibular canal involvement | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Osteosclerosis | 13 | 13 | 53 | 10 | 66 | 10 | 0.368 |

| Periosteal reaction | 11 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Persistent alveolar socket | 9 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 23 | 4 | 0.004 |

| Sinus implication | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.024 |

| Cortical bone perforation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Pathological fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| MRONJ | Non-MRONJ | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | (n = 48) | (n = 33) | (n = 81) | p * | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sclerotic trabecular bone pattern | 48 | 100 | 27 | 82 | 75 | 93 | 0.003 |

| Osteosclerosis | 37 | 77 | 19 | 58 | 56 | 69 | 0.087 |

| Osteolysis | 31 | 65 | 14 | 42 | 45 | 56 | 0.069 |

| Lamina dura thickening | 29 | 60 | 17 | 52 | 46 | 57 | 0.497 |

| Cortical bone perforation | 10 | 21 | 2 | 6 | 12 | 15 | 0.110 |

| Mandibular canal involvement | 9 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 0.009 |

| Bone sequestration | 9 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 0.009 |

| Periosteal reaction | 5 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 0.076 |

| Persistent alveolar socket | 5 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 0.695 |

| Sinus implication | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0.267 |

| Pathological fracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Region | Jaw | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRIm | MRONJ | Non-MRONJ | Total | p * | MRONJ | Non-MRONJ | Total | p * | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| PAN | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 79 | 76 | 558 | 100 | 637 | 96 | 19 | 56 | 185 | 99 | 204 | 92 | ||

| Medium | 22 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 3 | 0.003 | 14 | 41 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 7 | 0.000 |

| High | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 102 | 100 | 558 | 100 | 660 | 100 | 34 | 100 | 186 | 100 | 220 | 100 | ||

| CBCT | ||||||||||||||

| Low | 34 | 71 | 33 | 100 | 67 | 83 | 6 | 38 | 11 | 100 | 17 | 63 | ||

| Medium | 13 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 16 | 0.003 | 8 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 30 | 0.004 |

| High | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7 | ||

| Total | 48 | 100 | 33 | 100 | 81 | 100 | 16 | 100 | 11 | 100 | 27 | 100 | ||

| MRONJ Staging (AAOMS) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | Total | ||||||||

| CRIm PAN | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | p | r |

| Low | 88 | 95 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 91 | 83 | 0.000 * | 0.743 ** |

| Medium | 5 | 5 | 4 | 57 | 5 | 63 | 1 | 50 | 15 | 14 | ||

| High | 0 | 0 | 2 | 29 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 50 | 4 | 3 | ||

| Total | 93 | 100 | 7 | 100 | 8 | 100 | 2 | 100 | 110 | 100 | ||

| CRIm CBCT | ||||||||||||

| Low | 10 | 100 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 60 | 0.000 * | 0.877 *** |

| Medium | 0 | 0 | 2 | 67 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10 | ||

| High | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 75 | 3 | 100 | 6 | 30 | ||

| Total | 10 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 4 | 100 | 3 | 100 | 20 | 100 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeffman, M.W.; Koth, V.S.; Salum, F.G.; Rockenbach, M.I.; Morosolli, A.C.; Cherubini, K. Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Oral and Maxillofacial Status in Patients Undergoing Antiresorptive Therapy and Its Relationship with MRONJ. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123054

Jeffman MW, Koth VS, Salum FG, Rockenbach MI, Morosolli AC, Cherubini K. Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Oral and Maxillofacial Status in Patients Undergoing Antiresorptive Therapy and Its Relationship with MRONJ. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123054

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeffman, Marcela Wiltgen, Valesca Sander Koth, Fernanda Gonçalves Salum, Maria Ivete Rockenbach, Aline Cantarelli Morosolli, and Karen Cherubini. 2025. "Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Oral and Maxillofacial Status in Patients Undergoing Antiresorptive Therapy and Its Relationship with MRONJ" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123054

APA StyleJeffman, M. W., Koth, V. S., Salum, F. G., Rockenbach, M. I., Morosolli, A. C., & Cherubini, K. (2025). Clinical and Radiological Evaluation of Oral and Maxillofacial Status in Patients Undergoing Antiresorptive Therapy and Its Relationship with MRONJ. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3054. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123054