Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Diabetic Macular Edema: Clinical Significance and Prognostic Relevance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Brief Overview of Diabetic Macular Edema

3. Current Therapeutic Landscape

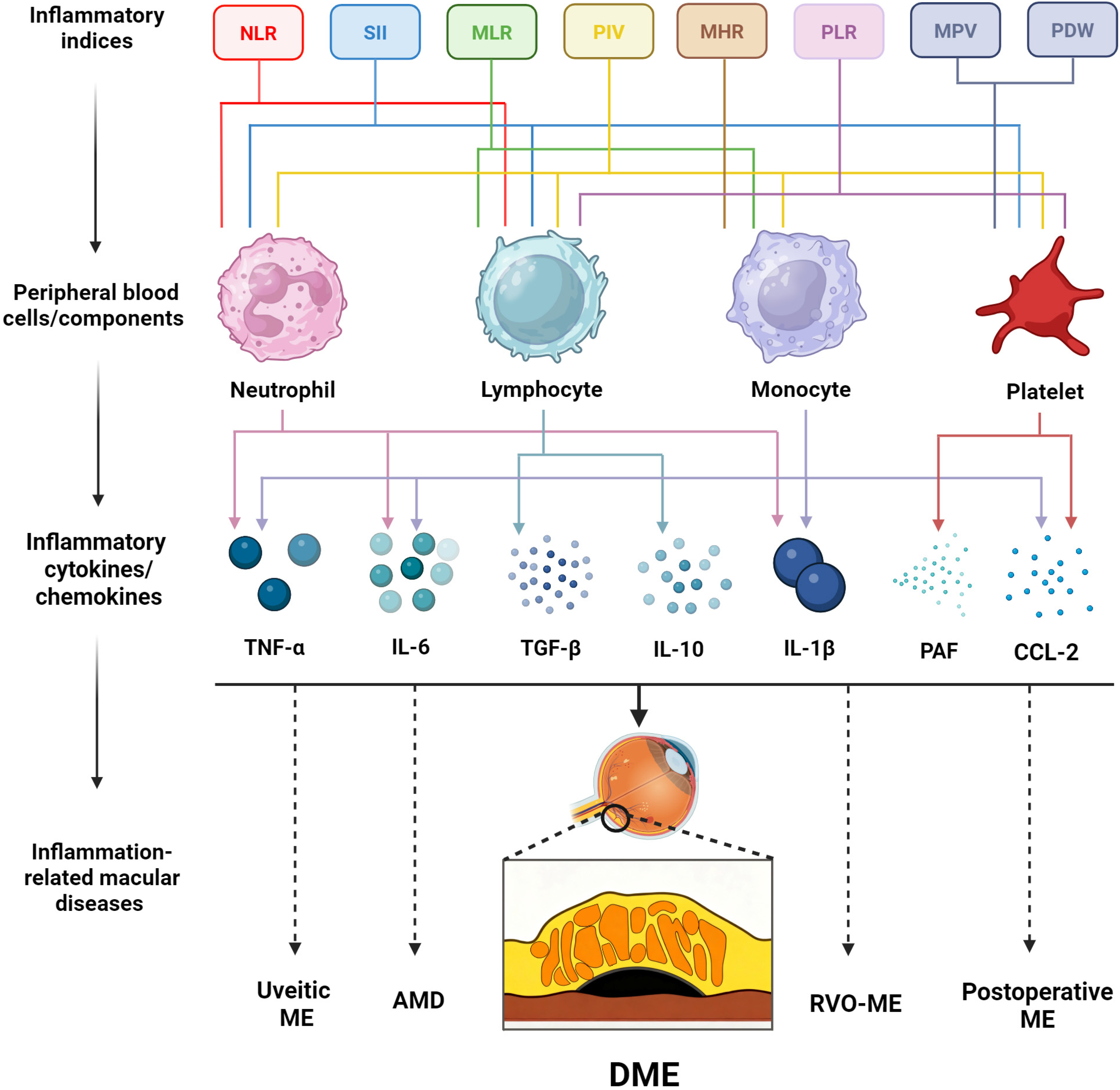

4. Inflammation in DME: Mechanistic Links to Biomarkers

5. Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in DME

5.1. White Blood Cell-Related Inflammatory Indices

5.1.1. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR)

5.1.2. Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR)

5.1.3. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII)

5.1.4. Monocyte-to-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio (MHR)

5.1.5. Monocyte-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (MLR)

5.1.6. Platelet-to-Neutrophil Ratio (PNR)

5.1.7. Pan-Immune-Inflammation Value (PIV)

5.2. Platelet-Related Inflammatory Indices

5.2.1. Mean Platelet Volume (MPV)

5.2.2. Platelet Distribution Width (PDW)

6. Evidence Grading and Clinical Classification

7. Summary and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BRB | Blood–retinal barrier |

| CME | Cystoid macular edema |

| CRT | Central retinal thickness |

| DME | Diabetic macular edema |

| DR | Diabetic retinopathy |

| DRT | Diffuse retinal thickening |

| LMR | Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio |

| LNR | Lymphocyte-to-neutrophil ratio |

| LPR | Lymphocyte-to-platelet ratio |

| MHR | Monocyte-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio |

| MLR | Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| MPV | Mean platelet volume |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PDW | Platelet distribution width |

| PIV | Pan-immune-inflammation value |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PNR | Platelet-to-neutrophil ratio |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| SII | Systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SRD | Serous retinal detachment |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Chen, Y.T.; Radke, N.V.; Amarasekera, S.; Park, D.H.; Chen, N.; Chhablani, J.; Wang, N.K.; Wu, W.C.; Ng, D.S.C.; Bhende, P.; et al. Updates on medical and surgical managements of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy. Asia Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 14, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Saeedi, P.; Basit, A.; Besançon, S.; Bommer, C.; Esteghamati, A.; Ogurtsova, K.; Zhang, P. Global and regional estimates and projections of diabetes-related health expenditure: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2020, 162, 108072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, Z.L.; Tham, Y.-C.; Yu, M.; Chee, M.L.; Rim, T.H.; Cheung, N.; Bikbov, M.M.; Wang, Y.X.; Tang, Y.; Lu, Y. Global prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and projection of burden through 2045: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Bourne, R.R.; Briant, P.S.; Flaxman, S.R.; Taylor, H.R.; Jonas, J.B.; Abdoli, A.A.; Abrha, W.A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.G. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: The Right to Sight: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e144–e160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ixcamey, M.; Palma, C. Diabetic macular edema. Dis. Mon. 2021, 67, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morya, A.K.; Ramesh, P.V.; Nishant, P.; Kaur, K.; Gurnani, B.; Heda, A.; Salodia, S. Diabetic retinopathy: A review on its pathophysiology and novel treatment modalities. World J. Methodol. 2024, 14, 95881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, N.T.; Kroeger, Z.A.; Lin, W.V.; Khanani, A.M.; Weng, C.Y. Novel Treatments for Diabetic Macular Edema and Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy. Curr. Diab Rep. 2021, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noma, H.; Yasuda, K.; Shimura, M. Involvement of Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Diabetic Macular Edema. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; McGuire, P.G.; Rangasamy, S. Diabetic Macular Edema: Pathophysiology and Novel Therapeutic Targets. Ophthalmology 2015, 122, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsos, G.; Christodoulou, E.; Christou, E.E.; Galanis, P.; Katsanos, A.; Limberis, L.; Stefaniotou, M. Vitreous inflammatory and angiogenic factors on patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy or diabetic macular edema: The role of Lipocalin2. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahulhameed, S.; Vishwakarma, S.; Chhablani, J.; Tyagi, M.; Pappuru, R.R.; Jakati, S.; Chakrabarti, S.; Kaur, I. A Systematic Investigation on Complement Pathway Activation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özata Gündoğdu, K.; Doğan, E.; Çelik, E.; Alagöz, G. Serum inflammatory marker levels in serous macular detachment secondary to diabetic macular edema. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 3637–3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Xiao, C. Serum inflammation biomarkers level in cystoid and diffuse diabetic macular edema. Int. Ophthalmol. 2024, 44, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeyli, A.; Kurtul, B.E.; Ozcan, S.C.; Ozarslan Ozcan, D. The diagnostic value of systemic immune-inflammation index in diabetic macular oedema. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2022, 105, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katić, K.; Katić, J.; Kumrić, M.; Božić, J.; Tandara, L.; Šupe Domić, D.; Bućan, K. The Predictors of Early Treatment Effectiveness of Intravitreal Bevacizumab Application in Patients with Diabetic Macular Edema. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Gu, L.; Luo, D.; Qiu, Q. Diabetic Macular Edema: Current Understanding, Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Cells 2022, 11, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madonna, R.; Balistreri, C.R.; Geng, Y.J.; De Caterina, R. Diabetic microangiopathy: Pathogenetic insights and novel therapeutic approaches. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017, 90, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Walker, G.B.; Kurji, K.; Fang, E.; Law, G.; Prasad, S.S.; Kojic, L.; Cao, S.; White, V.; Cui, J.Z.; et al. Parainflammation associated with advanced glycation endproduct stimulation of RPE in vitro: Implications for age-related degenerative diseases of the eye. Cytokine 2013, 62, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, I.; Gray, S.; Donnelly, R. Protein kinase C activation: Isozyme-specific effects on metabolism and cardiovascular complications in diabetes. Diabetologia 2001, 44, 659–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, U.; Lecomte, M.; Paget, C.; Ruggiero, D.; Wiernsperger, N.; Lagarde, M. Advanced glycation end-products induce apoptosis of bovine retinal pericytes in culture: Involvement of diacylglycerol/ceramide production and oxidative stress induction. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, L.P.; Avery, R.L.; Arrigg, P.G.; Keyt, B.A.; Jampel, H.D.; Shah, S.T.; Pasquale, L.R.; Thieme, H.; Iwamoto, M.A.; Park, J.E.; et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sewduth, R.N.; Kovacic, H.; Jaspard-Vinassa, B.; Jecko, V.; Wavasseur, T.; Fritsch, N.; Pernot, M.; Jeaningros, S.; Roux, E.; Dufourcq, P.; et al. PDZRN3 destabilizes endothelial cell-cell junctions through a PKCζ-containing polarity complex to increase vascular permeability. Sci. Signal 2017, 10, eaag3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Rauf, A.; Khan, H.; Abu-Izneid, T. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone (RAAS): The ubiquitous system for homeostasis and pathologies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 94, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, M.J.; Speth, R.C. The ocular renin-angiotensin system: A therapeutic target for the treatment of ocular disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 142, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckelings, U.M.; Rompe, F.; Kaschina, E.; Unger, T. The evolving story of the RAAS in hypertension, diabetes and CV disease: Moving from macrovascular to microvascular targets. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 23, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroba, A.I.; Valverde, Á.M. Modulation of microglia in the retina: New insights into diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol. 2017, 54, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, H.; Su, S.B. Neuroinflammatory responses in diabetic retinopathy. J. Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Smith, S.D.; Kaiser, P.K. Optical coherence tomographic patterns of diabetic macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2006, 142, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachin, J.M.; White, N.H.; Hainsworth, D.P.; Sun, W.; Cleary, P.A.; Nathan, D.M. Effect of intensive diabetes therapy on the progression of diabetic retinopathy in patients with type 1 diabetes: 18 years of follow-up in the DCCT/EDIC. Diabetes 2015, 64, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, C.C. Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive insulin therapy, by The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, D.V.; Wang, X.; Vedula, S.S.; Marrone, M.; Sleilati, G.; Hawkins, B.S.; Frank, R.N. Blood pressure control for diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, Cd006127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi, T. Current Treatments for Diabetic Macular Edema. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalinbas Yeter, D.; Eroglu, S.; Sariakcali, B.; Bozali, E.; Vural Ozec, A.; Erdogan, H. The Usefulness of Monocyte-to-High Density Lipoprotein and Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Diabetic Macular Edema Prediction and Early anti-VEGF Treatment Response. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergin, E.; Dascalu, A.M.; Stana, D.; Tribus, L.C.; Arsene, A.L.; Nedea, M.I.; Serban, D.; Nistor, C.E.; Tudor, C.; Dumitrescu, D.; et al. Predictive Role of Complete Blood Count-Derived Inflammation Indices and Optical Coherence Tomography Biomarkers for Early Response to Intravitreal Anti-VEGF in Diabetic Macular Edema. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, D.S.; Yoon, Y.H.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Bandello, F.; Maturi, R.K.; Augustin, A.J.; Li, X.Y.; Cui, H.; Hashad, Y.; Whitcup, S.M. Three-year, randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1904–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avitabile, T.; Longo, A.; Reibaldi, A. Intravitreal triamcinolone compared with macular laser grid photocoagulation for the treatment of cystoid macular edema. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2005, 140, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabal, B.; Teper, S.; Wylęgała, E. Subthreshold Micropulse Laser for Diabetic Macular Edema: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 12, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfiglio, V.; Rejdak, R.; Nowomiejska, K.; Zweifel, S.A.; Justus Wiest, M.R.; Romano, G.L.; Bucolo, C.; Gozzo, L.; Castellino, N.; Patane, C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Subthreshold Micropulse Yellow Laser for Persistent Diabetic Macular Edema After Vitrectomy: A Pilot Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 832448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boscia, F. Current approaches to the management of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular oedema. Drugs 2010, 70, 2171–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urias, E.A.; Urias, G.A.; Monickaraj, F.; McGuire, P.; Das, A. Novel therapeutic targets in diabetic macular edema: Beyond VEGF. Vis. Res. 2017, 139, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussen, A.M.; Poulaki, V.; Mitsiades, N.; Kirchhof, B.; Koizumi, K.; Döhmen, S.; Adamis, A.P. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs prevent early diabetic retinopathy via TNF-α suppression. FASEB J. 2002, 16, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; McGuire, P.G.; Monickaraj, F. Novel pharmacotherapies in diabetic retinopathy: Current status and what’s in the horizon? Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 64, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussen, A.M.; Poulaki, V.; Le, M.L.; Koizumi, K.; Esser, C.; Janicki, H.; Schraermeyer, U.; Kociok, N.; Fauser, S.; Kirchhof, B.; et al. A central role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. FASEB J. 2004, 18, 1450–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rübsam, A.; Parikh, S.; Fort, P.E. Role of Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, J.V.; Kuffova, L.; Delibegovic, M. The Role of Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabora, M.S.; Telli, M.E.; Fazil, K.; Erdur, S.K.; Ozsutcu, M.; Cekic, O.; Ozbilen, K.T. Serum and Aqueous Concentrations of Inflammatory Markers in Diabetic Macular Edema. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2016, 24, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.A.; Hartnett, M.E. Soluble mediators of diabetic macular edema: The diagnostic role of aqueous VEGF and cytokine levels in diabetic macular edema. Curr. Diab Rep. 2013, 13, 476–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starace, V.; Battista, M.; Brambati, M.; Cavalleri, M.; Bertuzzi, F.; Amato, A.; Lattanzio, R.; Bandello, F.; Cicinelli, M.V. The role of inflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic macular edema. Ther. Adv. Ophthalmol. 2021, 13, 25158414211055963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daruich, A.; Matet, A.; Moulin, A.; Kowalczuk, L.; Nicolas, M.; Sellam, A.; Rothschild, P.R.; Omri, S.; Gélizé, E.; Jonet, L.; et al. Mechanisms of macular edema: Beyond the surface. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 63, 20–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudraraju, M.; Narayanan, S.P.; Somanath, P.R. Regulation of blood-retinal barrier cell-junctions in diabetic retinopathy. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhan, C.; Citirik, M.; Uzel, M.M.; Kiziltoprak, H.; Tekin, K. The usefulness of systemic inflammatory markers as diagnostic indicators of the pathogenesis of diabetic macular edema. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2020, 83, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, S.; Thirunavukkarasu, A. A Clinico-Haematologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy. TNOA J. Ophthalmic Sci. Res. 2023, 61, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, A.; El-Emam, D.S.; Mohsen, T.A.; Hashish, A.M. Systemic Cellular Inflammatory Biomarkers in Diabetic Macular Edema. Egypt. J. Ophthalmol. (Mansoura Ophthalmic Cent.) 2024, 4, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; He, X.; Lu, Y.; Shi, G.; Zhu, Y.; Nie, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Association of the Monocyte-to-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Ratio With Diabetic Retinopathy. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 707008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Pan, C.; Li, D.; Zhou, X. The diagnostic value of platelet-to-neutrophil ratio in diabetic macular edema. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candan, O.; Orman, G.; Ünlü, N.; Ozkan, G. Diagnostic efficiency of pan-immune-inflammation value to predict diabetic macular edema and its relationship with OCT-based biomarkers of inflammation. Int. Ophthalmol. 2025, 45, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetikoğlu, M.; Aktas, S.; Sagdık, H.M.; Tasdemir Yigitoglu, S.; Özcura, F. Mean Platelet Volume is Associated with Diabetic Macular Edema in Patients with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 32, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.-D.; Mao, J.-B.; Cheng, D.; Shen, J.; Shen, L.-J. Correlation of mean platelet volume with diabetic macular edema in type 2 diabetic patients. Recent Adv. Ophthalmol. 2018, 6, 576–578. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Song, Y.; Cai, Q. Peripheral white blood cell subtypes and the development/progression of diabetic macular edema in type 2 diabetic patients: A comparative study. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 2887–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, B.; Mei, F.; Zhou, Q.; Yan, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Pretreatment neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in patients with diabetic macular edema treated with ranibizumab. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, E.; Hazar, L. Assessment of Inflammation Biomarkers in Diabetic Macular Edema Treated with Intravitreal Dexamethasone Implant. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 37, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Arabi, A.; Shahraki, T.; Safi, S. Association of White Blood Cell Counts, Leukocyte Ratios, and Serum Uric Acid with Clinical Outcome of Intravitreal Bevacizumab in Diabetic Macular Edema. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 36, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanxia, C.; Yongqiang, X.; Min, F.; Xiaoyun, K. A nomogram based on peripheral blood inflammatory indices and optical coherence tomography biomarkers for early prediction of anti-VEGF response in diabetic macular edema. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2025, 108, 1005–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Chen, Z.; Peng, F.; Deng, P.; Wang, M.; Liu, S.; Du, Y.; Zuo, G. Exploration Progress on Inflammatory Responses and Immune Regulatory Mechanisms in Diabetic Retinopathy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 11895–11909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Théroux, P. Clopidogrel inhibits platelet-leukocyte interactions and thrombin receptor agonist peptide-induced platelet activation in patients with an acute coronary syndrome. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2004, 43, 1982–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alyoruk, F.; Arican, E.; Turgut, B.; Ersan, I.; Erdogan, H.; Torun, S. Effects of blood HbA1c and mean platelet volume levels in diabetic macular edema patients who received dexamethasone implant. Eur. Eye Res. 2024, 4, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, D.K.; Lohr, K.N.; Atkins, D.; Treadwell, J.R.; Reston, J.T.; Bass, E.B.; Chang, S.; Helfand, M. AHRQ series paper 5: Grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health-care program. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2010, 63, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balshem, H.; Helfand, M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Kunz, R.; Brozek, J.; Vist, G.E.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Meerpohl, J.; Norris, S. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Aroca, P.; de la Riva-Fernandez, S.; Valls-Mateu, A.; Sagarra-Alamo, R.; Moreno-Ribas, A.; Soler, N. Changes observed in diabetic retinopathy: Eight-year follow-up of a Spanish population. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2016, 100, 1366–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development and Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy in Adolescents and Young Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: Results from the TODAY Study. Diabetes Care 2021, 45, 1049–1055. [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasooriya, T.; Athulgama, P.; Abeyek, M.; Dius, S.; Ranwala, R.; Bandar, S.; Godage, S.; Senadeera, S.; Wijepala, J. Macular Edema: Comprehensive Differential Diagnosis, Prognostic Biomarkers, and Multidisciplinary Management Strategies. Uva Clin. Anesth. Intensive Care 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Munk, M.R.; Sacu, S.; Huf, W.; Sulzbacher, F.; Mittermüller, T.J.; Eibenberger, K.; Rezar, S.; Bolz, M.; Kiss, C.G.; Simader, C.; et al. Differential diagnosis of macular edema of different pathophysiologic origins by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Retina 2014, 34, 2218–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, W.; Wang, M.; Li, Z.; Xu, T. The association between peripheral blood inflammatory markers and anti-VEGF treatment response in patients with type 2 diabetic macular edema. Front. Med. 2025, 12, 1653753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Qi, S.; Zhang, X.; Pan, J. The relationship between the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and diabetic retinopathy in adults from the United States: Results from the National Health and nutrition examination survey. BMC Ophthalmol. 2022, 22, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Year | Indices | Study Design | N | Diabetes Type | Control and Adjustment for Confounding Factors | Main Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Özata Gündoğdu et al., 2022 | NLR, PLR, SII, MPV | Retrospective | 120 | Not reported | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | The DME group shows a numerically higher but not statistically significant PLR. SRD subtype exhibits higher NLR, SII, and MPV values than those without SRD. | [12] |

| Liao et al., 2024 | NLR, SII, MLR | Retrospective | 50 | Not reported | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | NLR ≥ 2.27, SII ≥ 447, and MLR ≥ 0.24 are diagnostic thresholds for CME. | [13] |

| Elbeyli et al., 2022 | NLR, PLR, SII | Prospective | 150 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory or Immunosuppressive drugs, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | SII ≥ 399 is a diagnostic threshold for DME. The DME group demonstrates higher NLR, PLR, and SII values than DR-without-DME group. | [14] |

| Yalinbas Yeter et al., 2022 | NLR, MHR | Retrospective, cross-sectional | 143 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs, fibrates or niacin, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | NLR ≥ 2 and MHR ≥ 13.9 are diagnostic thresholds for DME. | [33] |

| Ilhan et al., 2020 | NLR, MPV | Prospective | 120 | T2DM | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | NLR ≥ 2.26 is a diagnostic threshold for DME. Patients with DME demonstrate the highest MPV. | [51] |

| Mani et al., 2023 | NLR, MPV | Case- control | 114 | T2DM | Control: anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents, smoke, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: age | Elevated NLR and MPV are associated with DME. | [52] |

| Mohamed et al., 2024 | PLR, MLR, MPV | Cohort | 120 | T2DM | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | The DME cohort exhibits elevated MLR, PLR, and MPV compared to diabetic patients without DME. | [53] |

| Tang et al., 2021 | MHR | Cross-sectional | 1378 | T2DM | Control: anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: age, sex | MHR is similar between non-DME and DME cases. | [54] |

| Sun et al., 2025 | PNR, MPV | Cross-sectional | 366 | T2DM | Control: antibiotics, immunosuppressants, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, steroids, or contraceptives, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: DR severity | PNR ≤ 68.51 is a diagnostic threshold for DME. MPV fails to distinguish OCT-defined DME subtypes. | [55] |

| Candan et al., 2025 | PIV | Case–control | 155 | Not reported | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: diabetes duration | PIV > 427.7 is a diagnostic threshold for DME. PIV > 451.3 separates DME from diabetes without retinopathy. | [56] |

| Tetikoğlu et al., 2016 | MPV | Retrospective | 199 | Not reported | Control: antiplatelet agents, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | The DME cohort exhibits elevated MPV compared with diabetics without DME. | [57] |

| Li et al., 2018 | MPV, PDW | Retrospective | 160 | T2DM | Control: nephrotoxic agents or antiplatelet agents, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: sex | The DME group demonstrates the highest MPV and PDW among healthy controls and diabetes without DME. | [58] |

| Zhu et al., 2022 | PDW | Retrospective | 114 | T2DM | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | There is no difference in PDW between the DME and DR-without-DME group. | [59] |

| Author and Year | Indices | Study Design | N | Diabetes Type | Control and Adjustment for Confounding Factors | Main Outcomes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katić et al., 2024 | NLR, PLR, SII, MLR | Prospective | 78 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs or substitutional vitamin D therapy, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: age, sex, C-reactive protein, disease duration | Lower baseline NLR, PLR, SII, and MLR predict a more favorable CRT outcome following anti-VEGF therapy. | [15] |

| Yalinbas Yeter et al., 2022 | NLR, MHR | Retrospective, cross-sectional | 143 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs, fibrates or niacin, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | Higher NLR predicts inferior CRT outcomes with anti-VEGF. | [33] |

| Hu et al., 2019 | NLR, MLR | Retrospective | 91 | Not reported | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | Higher NLR contributes to inferior visual outcomes with anti-VEGF. MLR is negatively correlated with visual improvement following treatment. | [60] |

| Ergin et al., 2025 | NLR, PLR, SII, MLR | Retrospective | 104 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory drugs, inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | NLR ≤ 2.32, PLR ≤ 120.55, SII ≤ 543.53 and MLR ≤ 0.21 correlates with early anti-VEGF therapeutic response in DME. | [34] |

| Vural et al., 2021 | NLR, MLR | Retrospective | 64 | T2DM | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | Elevated baseline NLR and MLR associate with a ≥1-line visual improvement following dexamethasone implantation. | [61] |

| Karimi et al., 2022 | LNR, LPR | Prospective | 80 | Not reported | Control: inflammation-related systemic diseases * No adjustment | Higher baseline LNR and LPR are correlated with larger improvement in visual acuity after anti-VEGF therapy. | [62] |

| Chen et al., 2025 | NLR, PLR | Retrospective | 140 | T2DM | Control: anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive drugs, inflammation-related systemic diseases * Adjustment: age, Scr, eGFR, TG | NLR > 2.57 and PLR > 98.93 are predictive indicators of poor visual prognosis after anti-VEGF therapy. | [63] |

| Indices | No. of Studies (n) | Prospective/Retrospective (n) | Studies Per Context * (DME vs. Non-DME/OCT-Based DME SubTypes/Anti-VEGF Treatment Response) | Total N per Study **, Median (Range) | ROC/AUC Studies (n) | AUC Range (Median) † | Evidence Grade ‡ | Clinical Category § |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | 12 | 3/9 | 9/4/3 | 120 (75–366) | 7 | 0.551–0.800 (0.686) | Moderate (Grade B) | Core indices |

| PLR | 10 | 3/7 | 7/3/3 | 120 (75–366) | 4 | 0.586–0.719 (0.676) | Moderate (Grade B) | Core indices |

| SII | 8 | 2/6 | 5/4/3 | 130 (75–366) | 4 | 0.613–0.788 (0.696) | Moderate (Grade B) | Core indices |

| MPV | 5 | 2/3 | 5/1/0 | 120 (120–160) | 2 | 0.650–0.741 (0.696) | Limited (Grade C) | Secondary indices |

| MLR | 7 | 2/5 | 4/1/3 | 120 (78–366) | 3 | 0.565–0.704 (0.638) | Limited (Grade C) | Secondary indices |

| MHR | 1 | 0/1 | 1/0/0 | 143 (143–143) | 1 | 0.690–0.690 (0.690) | Very limited | Exploratory indices |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, C.; Ye, W.; Wu, S.; Huang, Z. Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Diabetic Macular Edema: Clinical Significance and Prognostic Relevance. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122979

Lin C, Ye W, Wu S, Huang Z. Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Diabetic Macular Edema: Clinical Significance and Prognostic Relevance. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122979

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Chiyu, Weiqing Ye, Suyao Wu, and Zijing Huang. 2025. "Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Diabetic Macular Edema: Clinical Significance and Prognostic Relevance" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122979

APA StyleLin, C., Ye, W., Wu, S., & Huang, Z. (2025). Blood Cell-Derived Inflammatory Indices in Diabetic Macular Edema: Clinical Significance and Prognostic Relevance. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2979. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122979