An Immune Gene Signature Stratifies Breast Cancer Prognosis Through iCAF-Driven Immunosuppressive Microenvironment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Identification of Immune-Related Genes

2.2. Construction and Evaluation of the Immune-Related Gene Signature

2.3. CIBERSORT Analysis and Statistical Methods

2.4. Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Analysis

3. Results

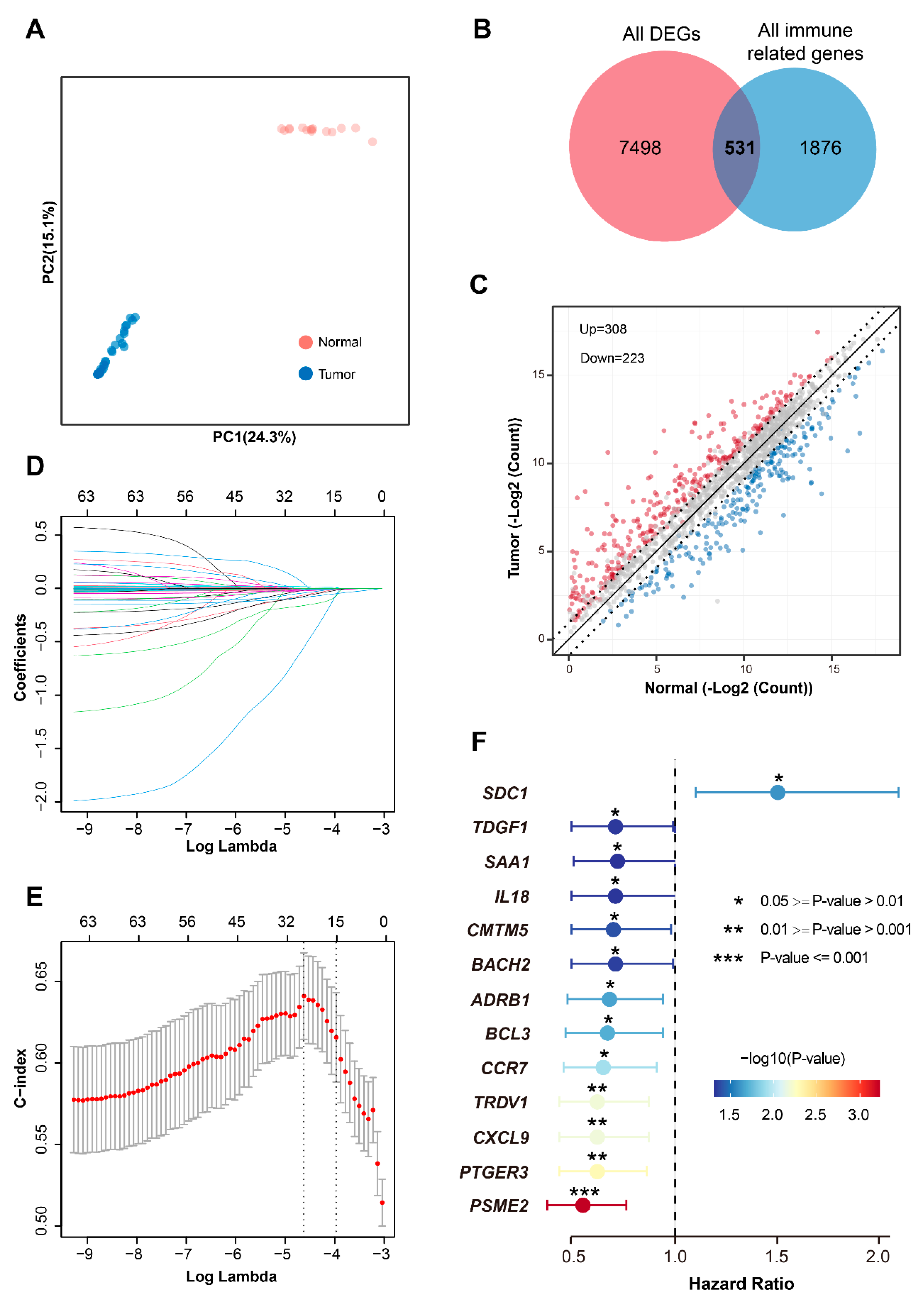

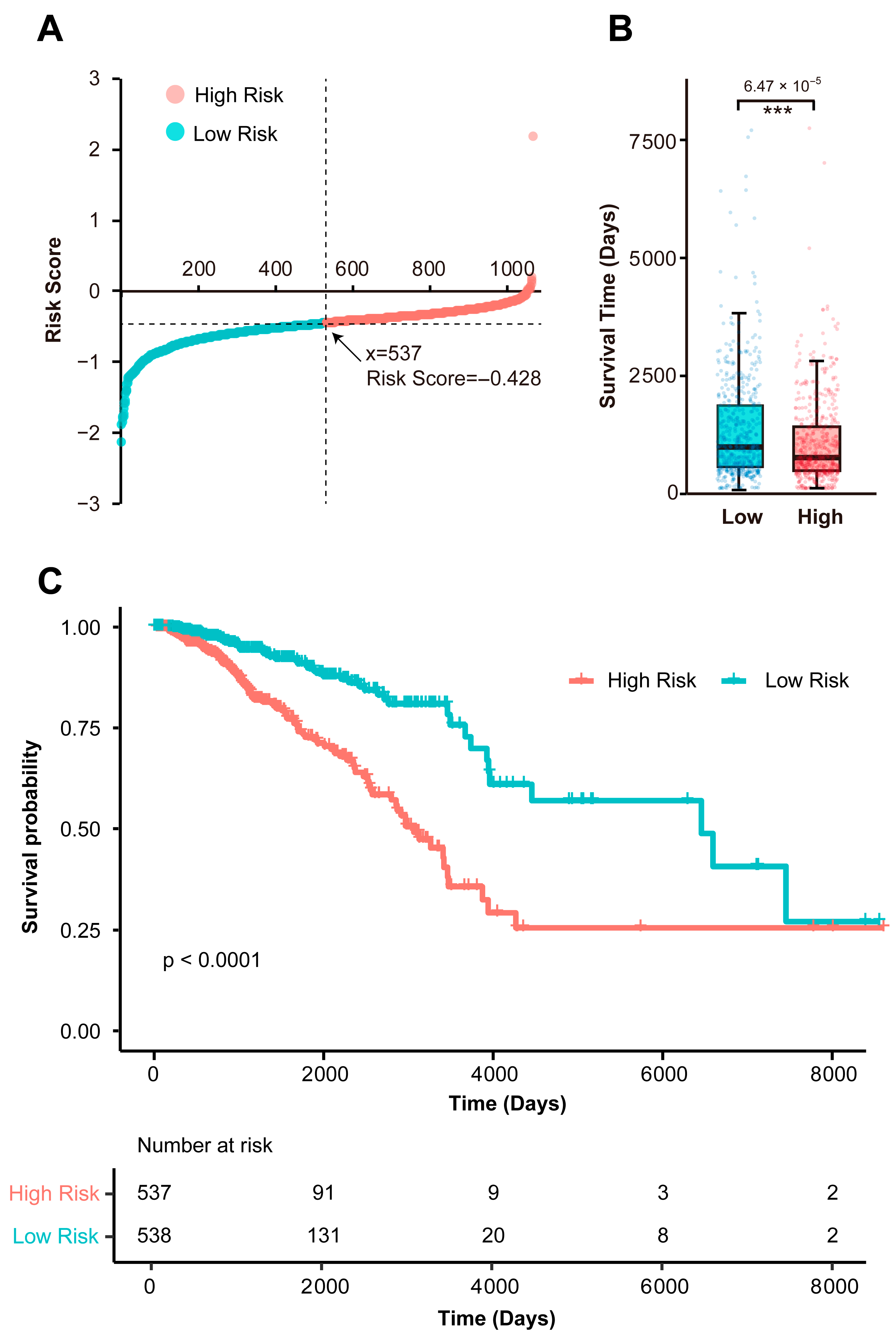

3.1. Identification of a Prognostic Immune Gene Signature

3.2. Biological Characterization of the Immune-Related Gene Prognostic Signature

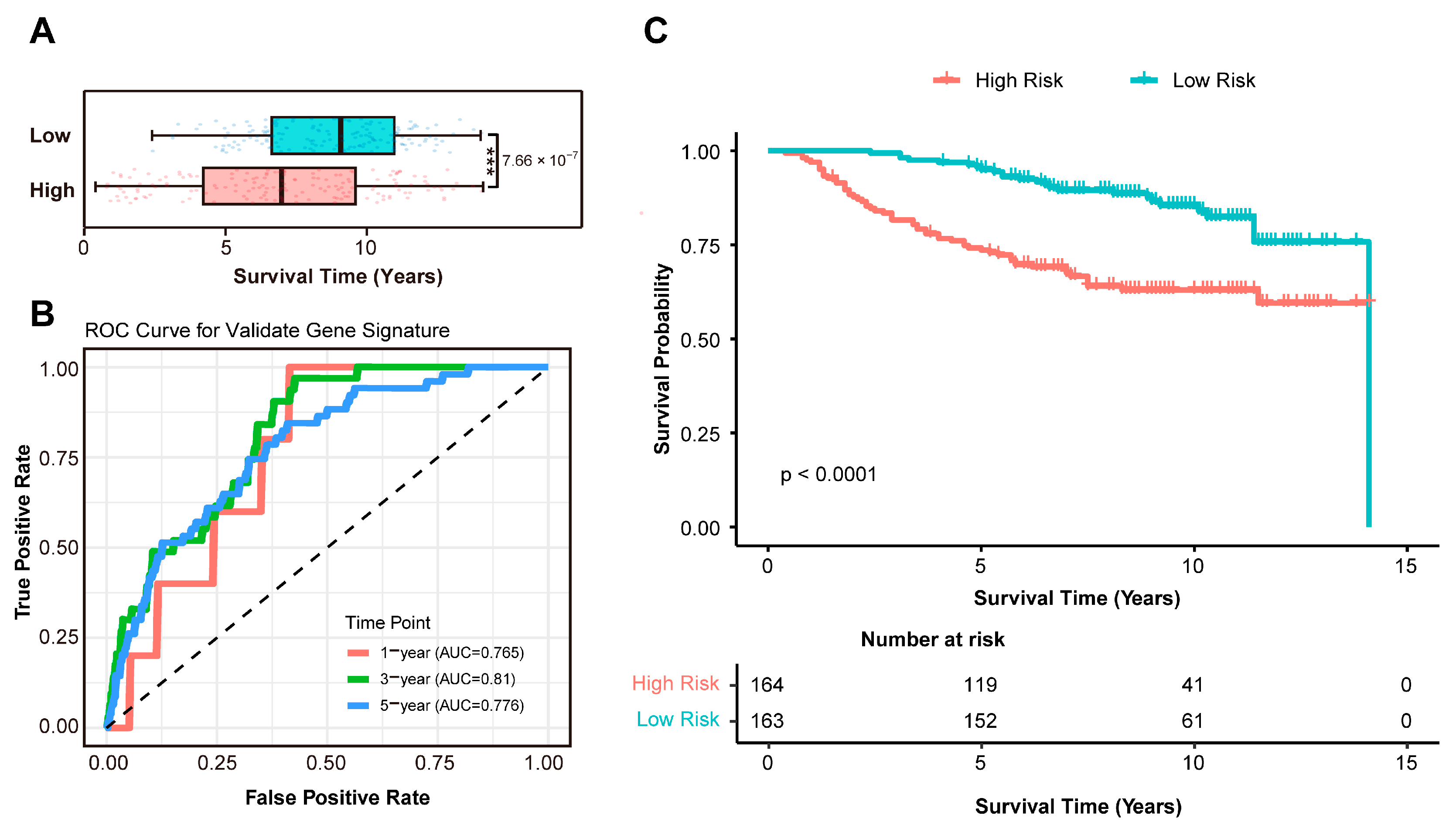

3.3. Independent Validation of the Prognostic Signature in an External Cohort

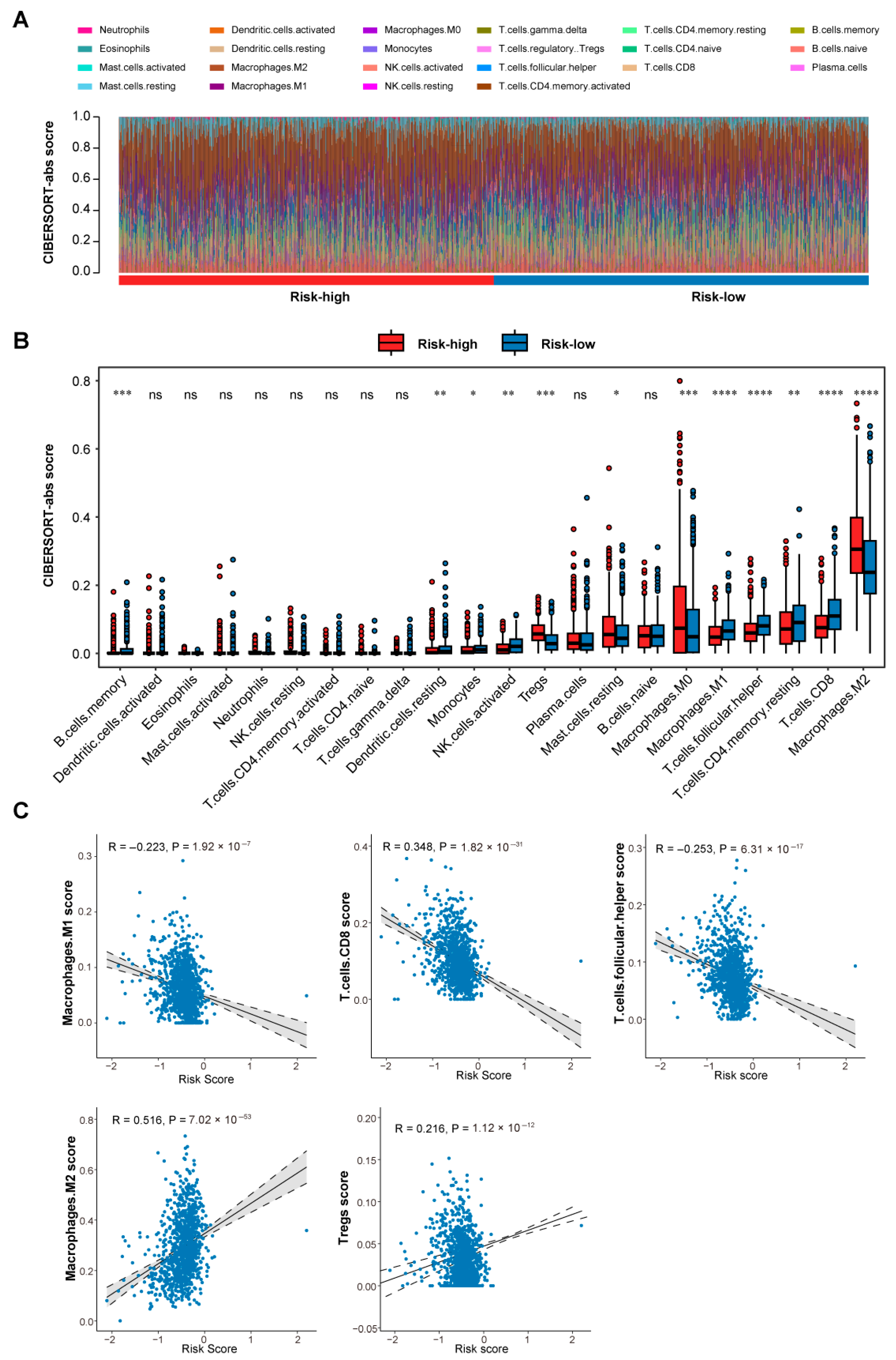

3.4. Differential Immune Microenvironment Landscapes Between Risk Groups

3.5. Single-Cell Dissection of Risk-Associated Microenvironments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilkinson, L.; Gathani, T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br. J. Radiol. 2022, 95, 20211033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapani, D.; Ginsburg, O.; Fadelu, T.; Lin, N.U.; Hassett, M.; Ilbawi, A.M.; Anderson, B.O.; Curigliano, G. Global challenges and policy solutions in breast cancer control. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 104, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Breast cancer: A review of risk factors and diagnosis. Medicine 2024, 103, e36905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badve, S.; Gokmen-Polar, Y. Tumor Heterogeneity in Breast Cancer. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2015, 22, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyak, K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3786–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testa, U.; Castelli, G.; Pelosi, E. Breast cancer: A molecularly heterogenous disease needing subtype-specific treatments. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, H.; Kawase, K.; Nishi, T.; Watanabe, T.; Takenaga, K.; Inozume, T.; Ishino, T.; Aki, S.; Lin, J.; Kawashima, S. Immune evasion through mitochondrial transfer in the tumour microenvironment. Nature 2025, 638, 225–236, Erratum in Nature 2025, 639, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Q.; Yuan, P.; Mei, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Kang, X.; Zheng, S.; Yang, C.; et al. Spatially resolved atlas of breast cancer uncovers intercellular machinery of venular niche governing lymphocyte extravasation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Yan, P.; Wang, D.; Bai, L.; Liang, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, H.; Ding, C.; Wei, H.; Wang, Y. Targeting lactylation reinforces NK cell cytotoxicity within the tumor microenvironment. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Ritter, J.; Brea, E.J.; Mahadevan, N.R.; Dillon, D.A.; Park, S.-R.; Liu, E.M.; Tolstorukov, M.Y.; McGourty, W.E. Immune targeting of triple-negative breast cancer through a clinically actionable STING agonist-CAR T cell platform. Cell Rep. 2025, 6, 102198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yang, L.; Ge, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, B.; Yang, C.; Gao, H.; Yang, M.; Zhu, T.; Wang, K. Neoadjuvant anlotinib/sintilimab plus chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (NeoSACT): Phase 2 trial. Cell Rep. 2025, 6, 102193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, D.C.; Shevde, L.A. The tumor microenvironment innately modulates cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 4557–4566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.A.; Patel, V.P.; Bhosle, K.P.; Nagare, S.D.; Thombare, K.C. The tumor microenvironment: Shaping cancer progression and treatment response. J. Chemother. 2025, 37, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Jiang, Y.-C.; Sun, C.-K.; Chen, Q.-M. Role of the tumor microenvironment in tumor progression and the clinical applications. Oncol. Rep. 2016, 35, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossevold, A.H.; Tekpli, X.; Lingjaerde, O.C.; Russnes, H.G.; Vallon-Christersson, J.; Borgen, E.; Lomo, J.; Garred, O.; Dorraji, E.; Kristensen, V.N.; et al. High tumor expression of CTLA4 identifies lymph node-negative basal-like breast cancer patients with excellent prognosis. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C.; Cao, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, L. Immune cell infiltration-based signature for prognosis and immunogenomic analysis in breast cancer. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, 2020–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Zhou, C.; Chen, S. A signature of 14 immune-related gene pairs predicts overall survival in gastric cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Gu, S.; Bao, S.; Yan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, P.; Zhou, M.; Sun, J. Mechanistically derived patient-level framework for precision medicine identifies a personalized immune prognostic signature in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Brief. Bioinform. 2021, 22, bbaa069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hong, Y.; Meng, S.; Gong, W.; Ren, T.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Li, L.; Qiu, L.; Qian, Z. A novel immune-related epigenetic signature based on the transcriptome for predicting the prognosis and therapeutic response of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 243, 109105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Peng, W.; Cheng, B.; Wang, R.; Chen, W.; Liu, L.; Huang, H.; Chen, S.; Cui, H.; Liang, J. PPY-Induced iCAFs Cultivate an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment in Pancreatic Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2413432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Liu, S.; Song, H.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses revealing tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zou, J.J.N.M. Advancing precision oncology with large, real-world genomics and treatment outcomes data. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1544–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosinsky, A.; Ambrose, J.; Cross, W.; Turnbull, C.; Henderson, S.; Jones, L.; Hamblin, A.; Arumugam, P.; Chan, G.; Chubb, D. Insights for precision oncology from the integration of genomic and clinical data of 13,880 tumors from the 100,000 Genomes Cancer Programme. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.; Suzek, T.O.; Troup, D.B.; Wilhite, S.E.; Ngau, W.-C.; Ledoux, P.; Rudnev, D.; Lash, A.E.; Fujibuchi, W.; Edgar, R. NCBI GEO: Mining millions of expression profiles—Database and tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33 (Suppl. S1), D562–D566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Hackl, H.; Charoentong, P.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Pages, F.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. ClueGO: A Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Andorf, S.; Gomes, L.; Dunn, P.; Schaefer, H.; Pontius, J.; Berger, P.; Desborough, V.; Smith, T.; Campbell, J. ImmPort: Disseminating data to the public for the future of immunology. Immunol. Res. 2014, 58, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Liu, C.L.; Newman, A.M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Profiling tumor infiltrating immune cells with CIBERSORT. In Cancer Systems Biology: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 243–259. [Google Scholar]

- Satija, R.; Farrell, J.A.; Gennert, D.; Schier, A.F.; Regev, A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Zhang, L.; Chang, I.; Ramos, R.; Kuan, C.-H.; Myung, P.; Plikus, M.V.; Nie, Q. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Miura, K.; Tamori, S.; Akimoto, K. Identification of a Gene Expression Signature to Predict the Risk of Early Recurrence and the Degree of Immune Cell Infiltration in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2024, 21, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsthuber, A.; Aschenbrenner, B.; Korosec, A.; Jacob, T.; Annusver, K.; Krajic, N.; Kholodniuk, D.; Frech, S.; Zhu, S.; Purkhauser, K. Cancer-associated fibroblast subtypes modulate the tumor-immune microenvironment and are associated with skin cancer malignancy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cords, L.; Tietscher, S.; Anzeneder, T.; Langwieder, C.; Rees, M.; de Souza, N.; Bodenmiller, B. Cancer-associated fibroblast classification in single-cell and spatial proteomics data. Nature 2023, 14, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.-k.; Deng, Z.-k-.; Chen, M.-t.; Qiu, S.-q.; Xiao, Y.-s.; Qi, Y.-z.; Xie, Q.; Wang, Z.-h.; Jia, S.-c.; Zeng, D. CXCL9 is a potential biomarker of immune infiltration associated with favorable prognosis in ER-negative breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 710286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Sun, S.; Qu, F.; Sun, M.; Liu, X.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, L.; Zheng, Y.; Su, G. Immunotherapy, CXCL9 influences the tumor immune microenvironment by stimulating JAK/STAT pathway in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2023, 72, 1479–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Ren, X.; Sun, Q.; Liang, Z. CXC motif chemokine ligand 9 correlates with favorable prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer by promoting immune cell infiltration. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 1493–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Kato, S.; Oizumi, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Inoue, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Akira, S.; Mckenzie, A.N.; Young, H.A.; Hoshino, T.J.B. The Journal of the American Society of Hematology, Interleukin 18 (IL-18) in synergy with IL-2 induces lethal lung injury in mice: A potential role for cytokines, chemokines, and natural killer cells in the pathogenesis of interstitial pneumonia. Blood J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 2002, 99, 1289–1298. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, N.; Li, W.; Fujimoto, Y.; Matsushita, Y.; Katagiri, T.; Okamura, H.; Miyoshi, Y. High serum levels of interleukin-18 are associated with worse outcomes in patients with breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 5009–5018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhadary, M.; Elsayed, B.; Elshoeibi, A.M.; Karen, O.; Elmakaty, I.; Alhmoud, J.; Hamdan, A.; Malki, M.I. The Clinicopathological and Prognostic Value of CCR7 Expression in Breast Cancer Throughout the Literature: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Yu, S.; Chen, J.; Hou, Q.; Wang, S.; Qian, C.; Yin, S. Risk stratification based on DNA damage-repair-related signature reflects the microenvironmental feature, metabolic status and therapeutic response of breast cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1127982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Hao, H. The importance of cancer-associated fibroblasts in targeted therapies and drug resistance in breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2024, 13, 1333839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Li, Z.; Zheng, B.; Lin, X.; Pan, Y.; Gong, P.; Zhuo, W.; Hu, Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, L. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Commun. 2022, 42, 401–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desbois, M.; Wang, Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Key players in shaping the tumor immune microenvironment. Immunol. Rev. 2021, 302, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Xu, J.; Wang, W.; Liang, C.; Hua, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yu, X.; Shi, S. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: New findings and future perspectives. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Niu, Y.-R.; Wang, Z.-H.; Ye, L.-L.; Peng, W.-B.; Zhou, Q. Cancer-associated fibroblasts: Vital suppressors of the immune response in the tumor microenvironment. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2022, 67, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneberg, P. Paracrine tumor signaling induces transdifferentiation of surrounding fibroblasts. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2016, 97, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, L.; Huang, G.; Song, H.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L. Cancer associated fibroblasts: An essential role in the tumor microenvironment. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croizer, H.; Mhaidly, R.; Kieffer, Y.; Gentric, G.; Djerroudi, L.; Leclere, R.; Pelon, F.; Robley, C.; Bohec, M.; Meng, A. Deciphering the spatial landscape and plasticity of immunosuppressive fibroblasts in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Lyu, H.; Chen, Q.; Bai, Y.; Yu, J.; Cai, R. Molecular Characteristics of Prognosis and Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer: Biomarker Identification Based on Gene Mutations and Pathway. J. Breast Cancer 2025, 28, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.T.; Nguyen Hoang, V.-A.; Nguyen Trieu, V.; Pham, T.H.; Dinh, T.C.; Pham, D.H.; Nguyen, N.; Vinh, D.N.; Do, T.T.T.; Nguyen, D.S. Personalized mutation tracking in circulating-tumor DNA predicts recurrence in patients with high-risk early breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 58, Erratum in NPJ Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Li, C. Development of a prognostic model for breast cancer patients based on intratumoral tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using machine learning algorithms. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, X.; Pei, J.; Han, C.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, G.; Chen, N.; Zheng, W.; Meng, F.; Yu, D.; Chen, Y. A multimodal machine learning model for the stratification of breast cancer risk. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2025, 9, 356–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Park, J.; Yeung, F.; Goldberg, E.; Heacock, L.; Shamout, F.; Geras, K.J. Leveraging transformers to improve breast cancer classification and risk assessment with multi-modal and longitudinal data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.03217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Tan, Z.; Cui, H.; Ma, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, J.; Dai, L.; Kang, H.; Guan, F.; Dai, Z.J. Identification of glycogene signature as a tool to predict the clinical outcome and immunotherapy response in breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 854284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosson-Amedenu, S.; Ayitey, E.; Ayiah-Mensah, F.; Asare, L. Evaluating key predictors of breast cancer through survival: A comparison of AFT frailty models with LASSO, ridge, and elastic net regularization. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merzhevich, T.; Tanzanakis, A.; Salin, E.; Quiering, C.; Kurz, C.; Gmeiner, B.; Eskofier, B.M. Machine Learning Predictions of Overall and Progression-Free Survival in Advanced Breast Cancer; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Hu, C.; Na, J.; Hart, S.N.; Gnanaolivu, R.D.; Abozaid, M.; Rao, T.; Tecleab, Y.A.; Pesaran, T. Functional evaluation and clinical classification of BRCA2 variants. Nature 2025, 638, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Miao, X.; Song, Q.; Ding, H.; Rajan, S.A.P.; Skardal, A.; Votanopoulos, K.I.; Dai, K.; Zhao, W.; Lu, B. Detection of lineage-reprogramming efficiency of tumor cells in a 3D-printed liver-on-a-chip model. Theranostics 2023, 13, 4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sinjab, A.; Min, J.; Han, G.; Paradiso, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R.; Pei, G.; Dai, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Conserved spatial subtypes and cellular neighborhoods of cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single-cell spatial multi-omics. Cancer Cell 2025, 43, 905–924.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tian, L.; Bai, L.; Jia, Z.; Wu, X.; Song, C. Identification of hypertension gene expression biomarkers based on the DeepGCFS algorithm. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0314319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mei, S.; Bai, C.; Wang, H.; Lin, K.; Pan, T.; Lu, Y.; Cao, Q. An Immune Gene Signature Stratifies Breast Cancer Prognosis Through iCAF-Driven Immunosuppressive Microenvironment. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122966

Mei S, Bai C, Wang H, Lin K, Pan T, Lu Y, Cao Q. An Immune Gene Signature Stratifies Breast Cancer Prognosis Through iCAF-Driven Immunosuppressive Microenvironment. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122966

Chicago/Turabian StyleMei, Sibin, Chenhao Bai, Huijuan Wang, Kainan Lin, Tianyuan Pan, Yunkun Lu, and Qian Cao. 2025. "An Immune Gene Signature Stratifies Breast Cancer Prognosis Through iCAF-Driven Immunosuppressive Microenvironment" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122966

APA StyleMei, S., Bai, C., Wang, H., Lin, K., Pan, T., Lu, Y., & Cao, Q. (2025). An Immune Gene Signature Stratifies Breast Cancer Prognosis Through iCAF-Driven Immunosuppressive Microenvironment. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2966. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122966