Lactate Enhances Non-Homologous End Joining Repair and Chemoresistance Through Facilitating XRCC4–LIG4 Complex Assembly in Ovarian Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

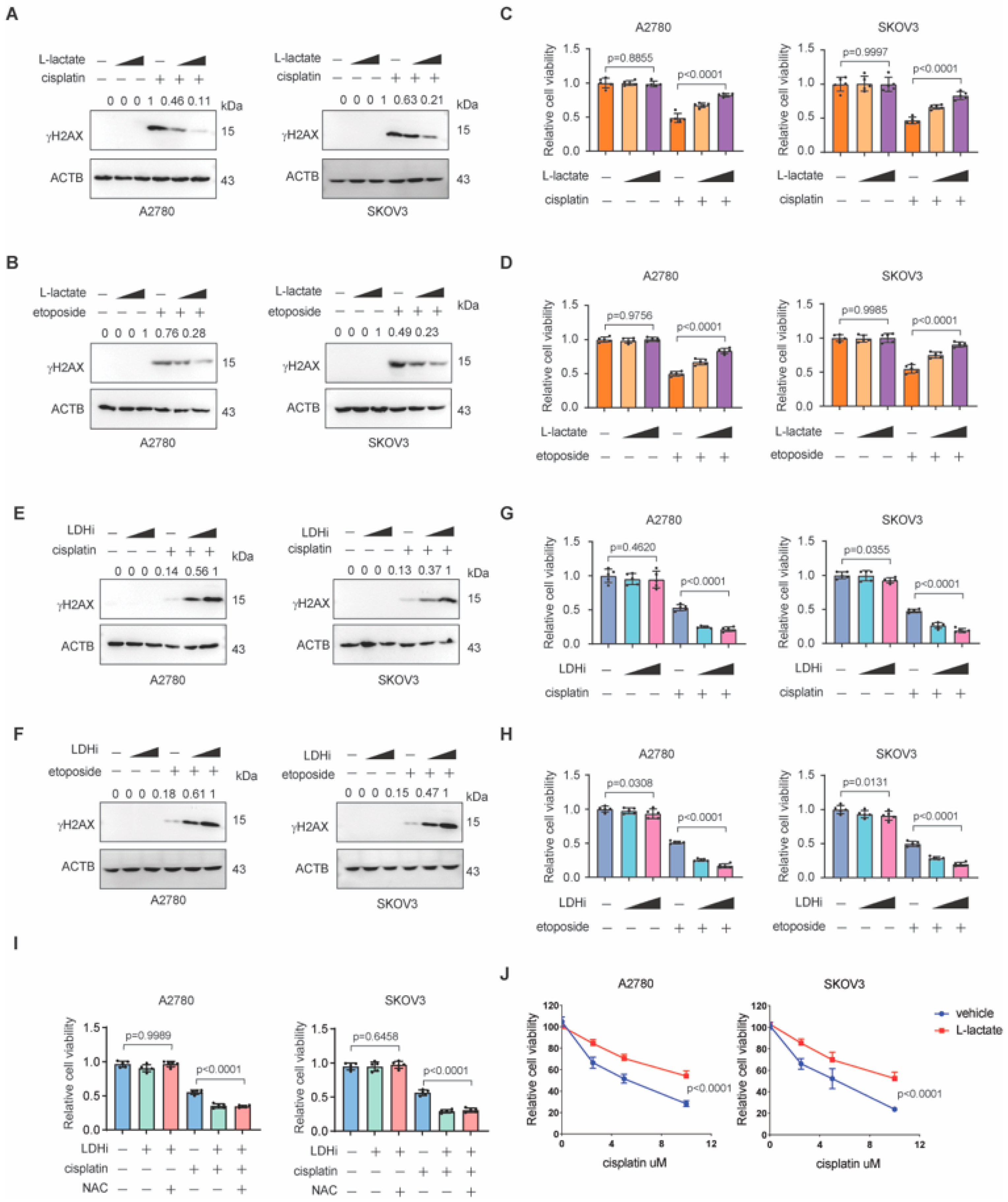

3.1. Lactate Promotes NHEJ Repair in Ovarian Cancer

3.2. Lactate Promotes Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer

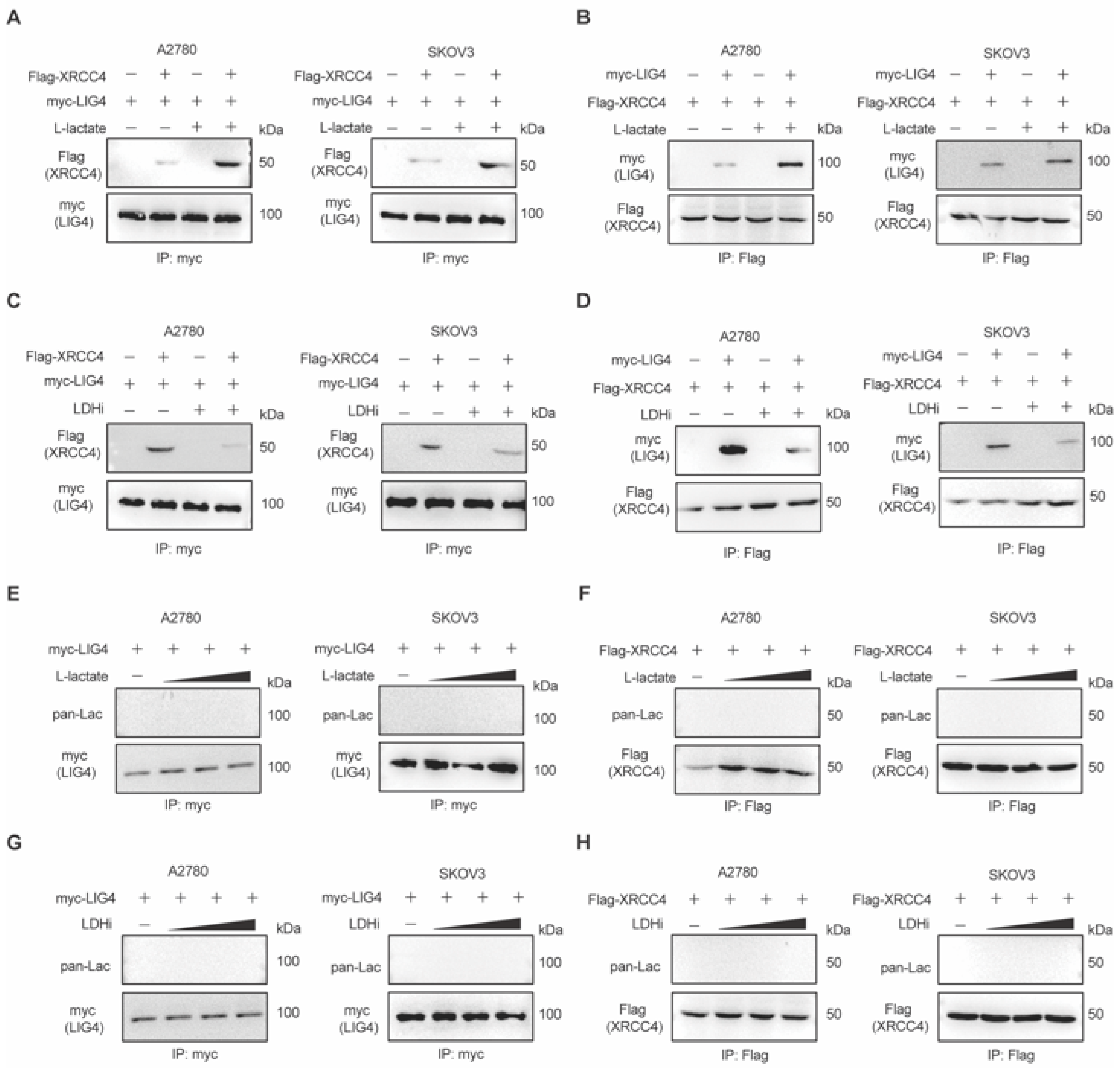

3.3. Lactate Promotes XRCC4–LIG4 Assembly to Facilitate NHEJ

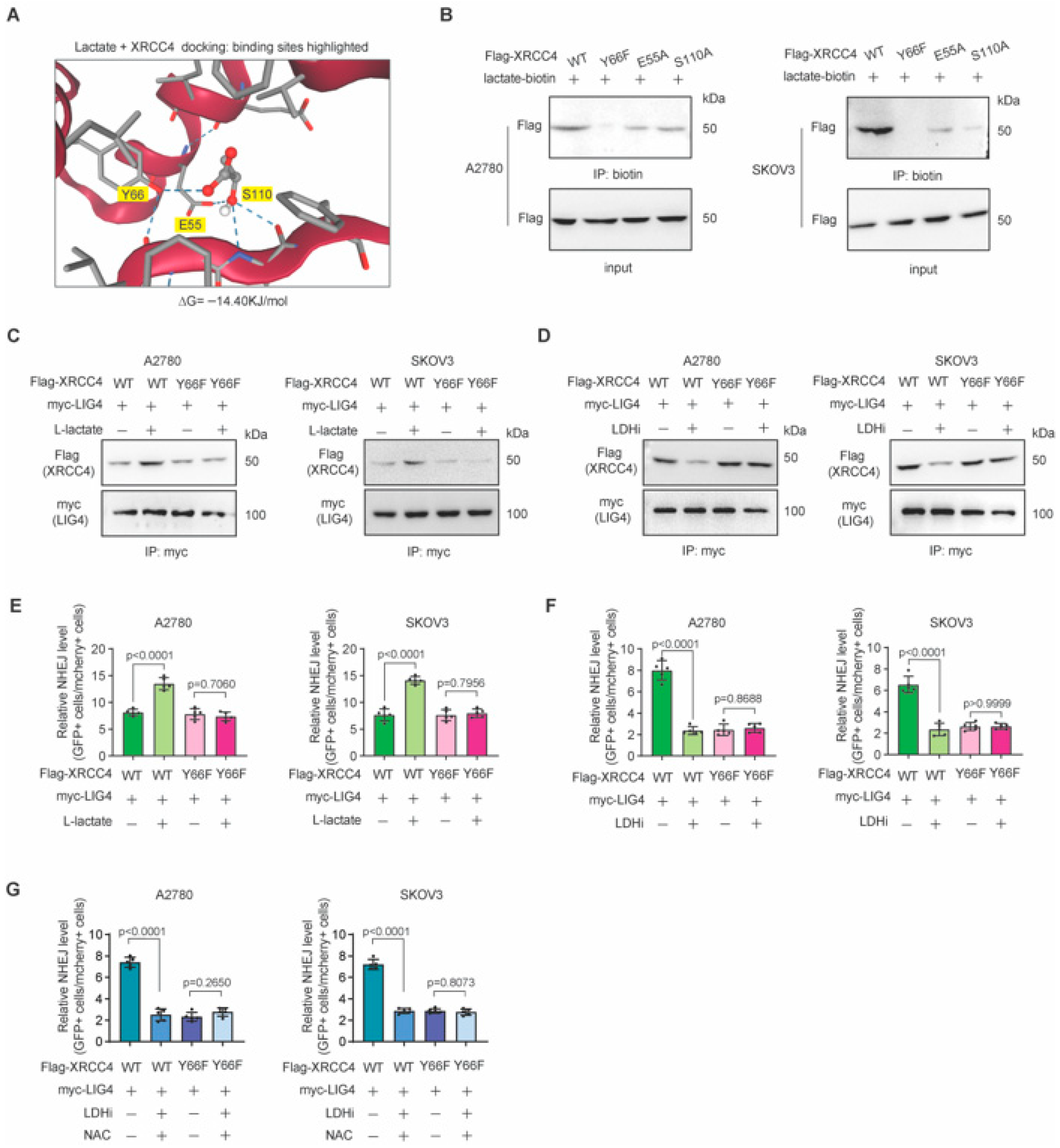

3.4. Lactate Directly Binds to XRCC4 to Promote XRCC4–LIG4 Interaction

3.5. Blocking Lactate-XRCC4 Binding Suppressed Lactate-Induced XRCC4–LIG4 Assembly and NHEJ Repair

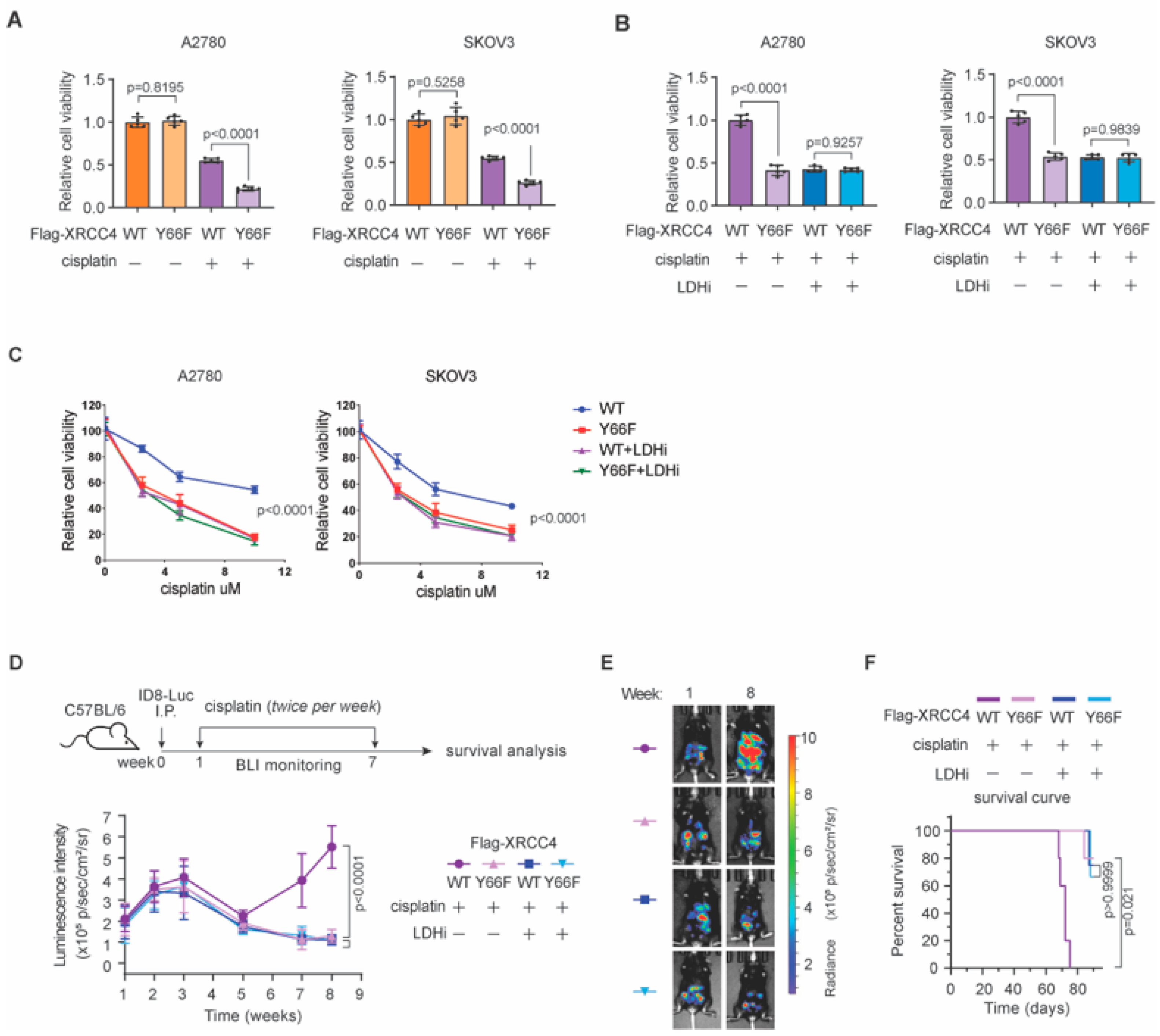

3.6. Lactate-Mediated NHEJ Repair Confers Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer In Vivo

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Kratzer, T.B.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2025, 75, 10–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lu, J.; Xu, M.; Yang, S.; Yu, T.; Zheng, C.; Huang, X.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Long, J.; et al. ODF2L acts as a synthetic lethal partner with WEE1 inhibition in epithelial ovarian cancer models. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e161544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rottenberg, S.; Disler, C.; Perego, P. The rediscovery of platinum-based cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, T.; Staszewski, M.; Markowicz-Piasecka, M.; Sikora, J.; Amaro, C.; Picot, L.; Mouray, E.; Pescitelli, G.; Girstun, A.; Król, M. Anticancer Activity of the Marine-Derived Compound Bryostatin 1: Preclinical and Clinical Evaluation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetan, R.; Lokman, N.A.; Eldi, P.; Price, Z.K.; Oehler, M.K.; Brooks, D.A.; O’Callaghan, M.E.; Tanwar, P.S.; Ricciardelli, C. Protease-Activated Receptor F2R Is a Potential Target for New Diagnostic/Prognostic and Treatment Applications for Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Pius, C.; Nabeel, M.; Nair, M.; Vishwanatha, J.K.; Ahmad, S.; Basha, R. Ovarian cancer: Current status and strategies for improving therapeutic outcomes. Cancer Med. 2019, 8, 7018–7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zheng, C.; Mai, Q.; Huang, X.; Pan, W.; Lu, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, H.; et al. Tyrosine catabolism enhances genotoxic chemotherapy by suppressing translesion DNA synthesis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 2044–2059.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, T.T. Reconsidering pathway choice: A sequential model of mammalian DNA double-strand break pathway decisions. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2021, 71, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Shi, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Sun, T.; Dong, Y.; Xue, C.; Zhu, X.; et al. HRD effects on first-line adjuvant chemotherapy and PARPi maintenance therapy in Chinese ovarian cancer patients. npj Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Xia, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Liu, J.; Zhou, D.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Qian, Y.; et al. Neoadjuvant PARPi or chemotherapy in ovarian cancer informs targeting effector Treg cells for homologous-recombination-deficient tumors. Cell 2024, 187, 4905–4925.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konstantinopoulos, P.A.; Ceccaldi, R.; Shapiro, G.I.; D’Andrea, A.D. Homologous Recombination Deficiency: Exploiting the Fundamental Vulnerability of Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 1137–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.R.; Ma, Y.; Pannicke, U.; Schwarz, K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Kim, W.; Gao, H.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, M.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, J.; Hu, Q.; et al. ASTE1 promotes shieldin-complex-mediated DNA repair by attenuating end resection. Nat. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scully, R.; Panday, A.; Elango, R.; Willis, N.A. DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fendt, S.M. 100 years of the Warburg effect: A cancer metabolism endeavor. Cell 2024, 187, 3824–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finley, L.W.S. What is cancer metabolism? Cell 2023, 186, 1670–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Tan, H.; Niu, G.; Huang, X.; Lu, J.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, M.; et al. ACAT1-Mediated ME2 Acetylation Drives Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer by Linking Glutaminolysis to Lactate Production. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2416467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.D.; Enerback, S. Lactate: The ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhai, L.; Zhang, T.; Yin, H.; Gao, H.; Zhao, F.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.; Jin, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of homologous recombination repair by MRE11 lactylation. Cell 2024, 187, 294–311.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Fu, H.; Mao, D.; Chen, W.; Lan, L.; Wang, C.; Hu, K.; et al. NBS1 lactylation is required for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature 2024, 631, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Bozi, L.H.M.; Fischer, P.D.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Xiao, H.; Wu, T.; Darabedian, N.; He, X.; Mills, E.L.; et al. Lactate regulates cell cycle by remodelling the anaphase promoting complex. Nature 2023, 616, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Ciszewski, W.M.; Kania, K.D. L- and D-lactate enhance DNA repair and modulate the resistance of cervical carcinoma cells to anticancer drugs via histone deacetylase inhibition and hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 1 activation. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, B.L.; Critchlow, S.E.; Begun, J.; Pei, X.Y.; Jackson, S.P.; Blundell, T.L.; Pellegrini, L. Crystal structure of an Xrcc4-DNA ligase IV complex. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanton, C.; Bernard, E.; Abbosh, C.; Andre, F.; Auwerx, J.; Balmain, A.; Bar-Sagi, D.; Bernards, R.; Bullman, S.; DeGregori, J.; et al. Embracing cancer complexity: Hallmarks of systemic disease. Cell 2024, 187, 1589–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Niu, G.; Tan, H.; Huang, X.; Lu, J.; Mai, Q.; Yu, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Wei, M.; et al. A noncanonical role of SAT1 enables anchorage independence and peritoneal metastasis in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Pan, C.; Boese, A.C.; Kang, J.; Umano, A.D.; Magliocca, K.R.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Lonial, S.; Jin, L.; et al. DGKA Provides Platinum Resistance in Ovarian Cancer Through Activation of c-JUN-WEE1 Signaling. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 3843–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Jin, L.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Chun, J.; Boese, A.C.; Li, D.; Kang, H.B.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, L.; et al. Inositol-triphosphate 3-kinase B confers cisplatin resistance by regulating NOX4-dependent redox balance. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2431–2445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Huang, B.; Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; He, Y.; Ding, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Lactylation of XLF promotes non-homologous end-joining repair and chemoresistance in cancer. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 2654–2672.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recuero-Checa, M.A.; Dore, A.S.; Arias-Palomo, E.; Rivera-Calzada, A.; Scheres, S.H.; Maman, J.D.; Pearl, L.H.; Llorca, O. Electron microscopy of Xrcc4 and the DNA ligase IV-Xrcc4 DNA repair complex. DNA Repair 2009, 8, 1380–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fugger, K.; Hewitt, G.; West, S.C.; Boulton, S.J. Tackling PARP inhibitor resistance. Trends Cancer 2021, 7, 1102–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Li, H.; Zheng, C.; Huang, X.; Chen, S.; Pan, C.; Li, J.; et al. Lactate Enhances Non-Homologous End Joining Repair and Chemoresistance Through Facilitating XRCC4–LIG4 Complex Assembly in Ovarian Cancer. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2949. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122949

Lu J, Zhu J, Zhang H, Zhou Z, Li H, Zheng C, Huang X, Chen S, Pan C, Li J, et al. Lactate Enhances Non-Homologous End Joining Repair and Chemoresistance Through Facilitating XRCC4–LIG4 Complex Assembly in Ovarian Cancer. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2949. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122949

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Jingyi, Jiayu Zhu, Huanxiao Zhang, Zhou Zhou, Haoyuan Li, Cuimiao Zheng, Xi Huang, Siqi Chen, Chaoyun Pan, Jie Li, and et al. 2025. "Lactate Enhances Non-Homologous End Joining Repair and Chemoresistance Through Facilitating XRCC4–LIG4 Complex Assembly in Ovarian Cancer" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2949. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122949

APA StyleLu, J., Zhu, J., Zhang, H., Zhou, Z., Li, H., Zheng, C., Huang, X., Chen, S., Pan, C., Li, J., & Tan, H. (2025). Lactate Enhances Non-Homologous End Joining Repair and Chemoresistance Through Facilitating XRCC4–LIG4 Complex Assembly in Ovarian Cancer. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2949. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122949