Shortcoming of the Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus: Small Intestinal Lengths Have Similar Variations in In- and Outbred Mice and Cannot Be Predicted by Allometric Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

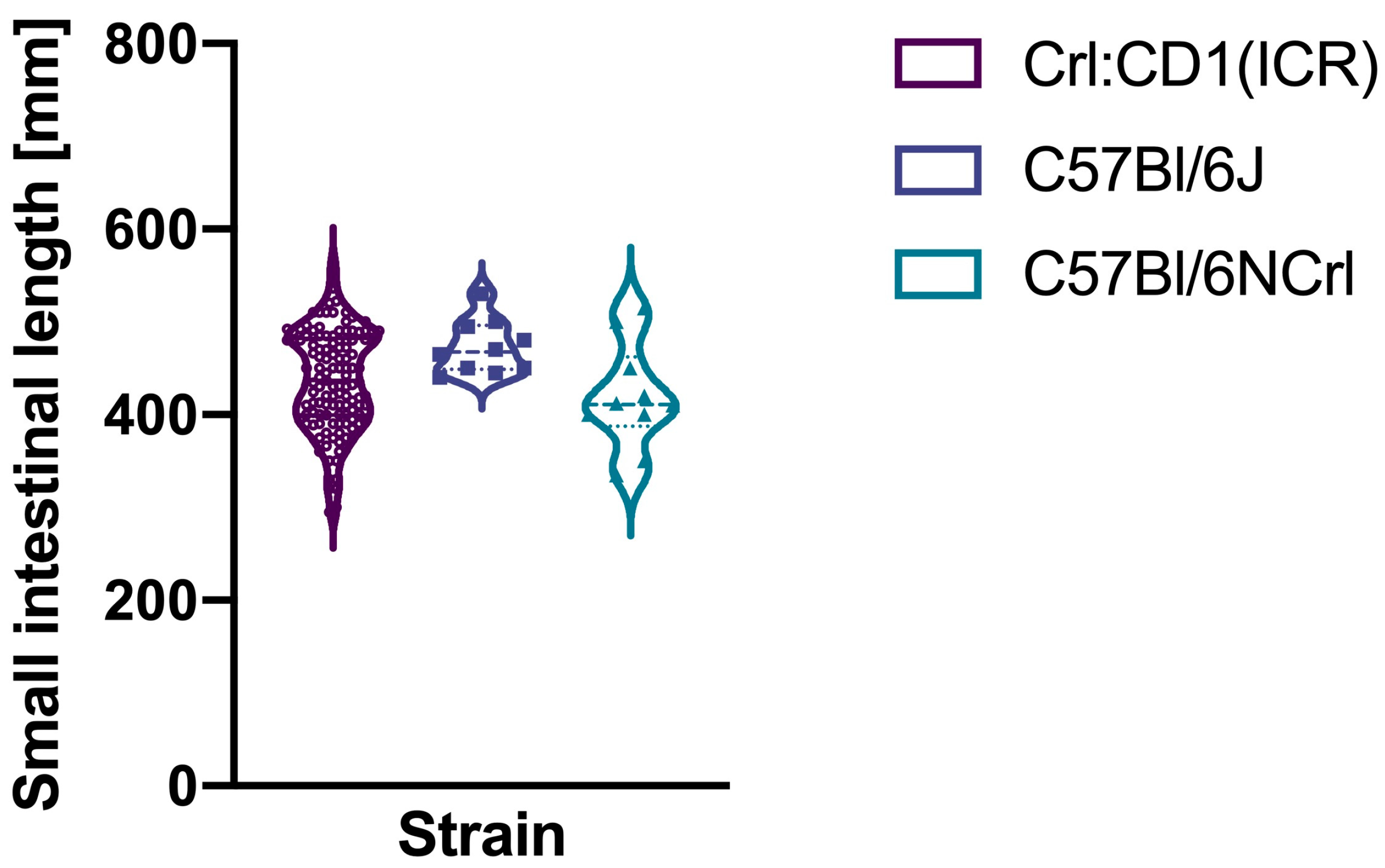

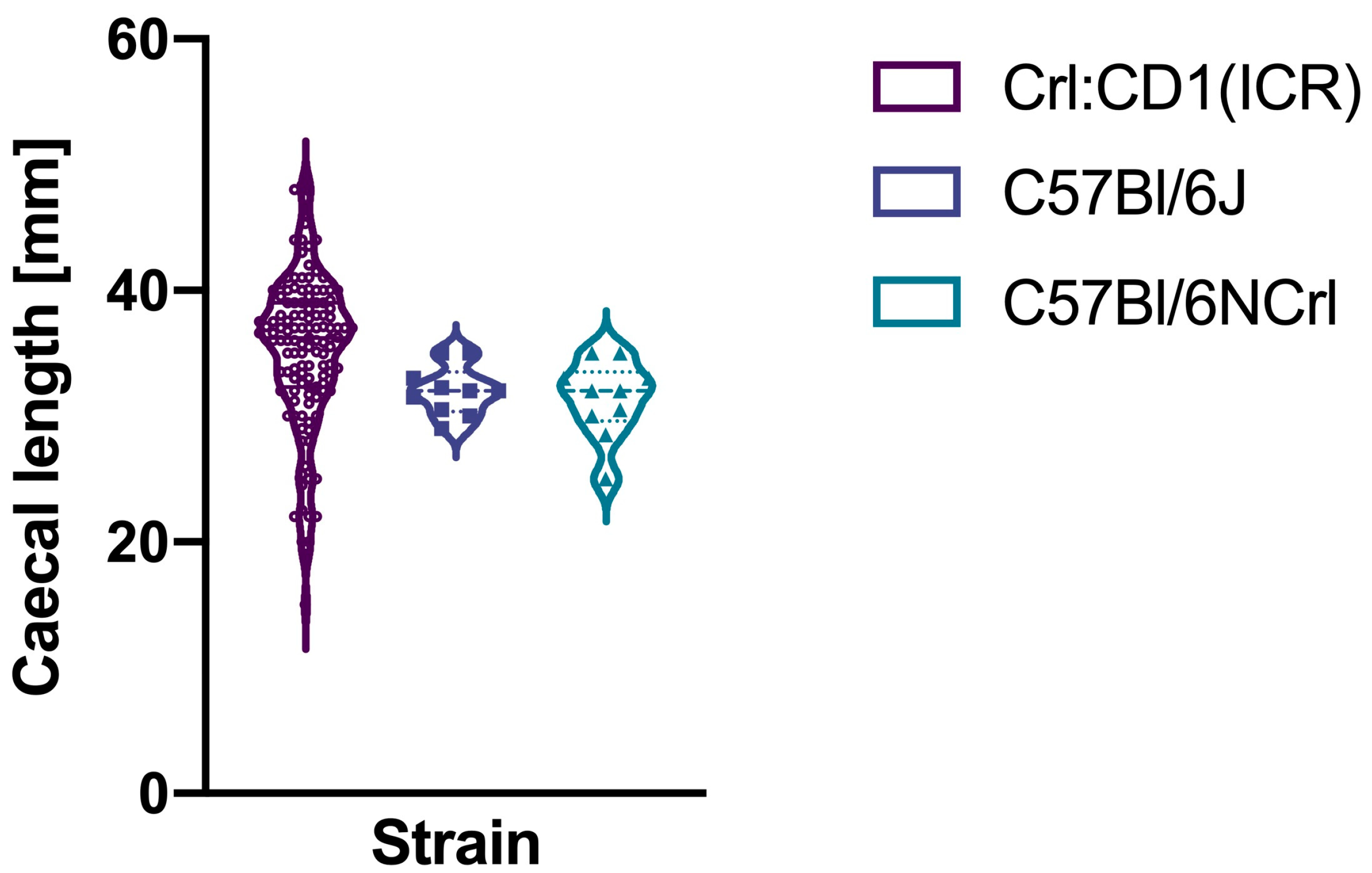

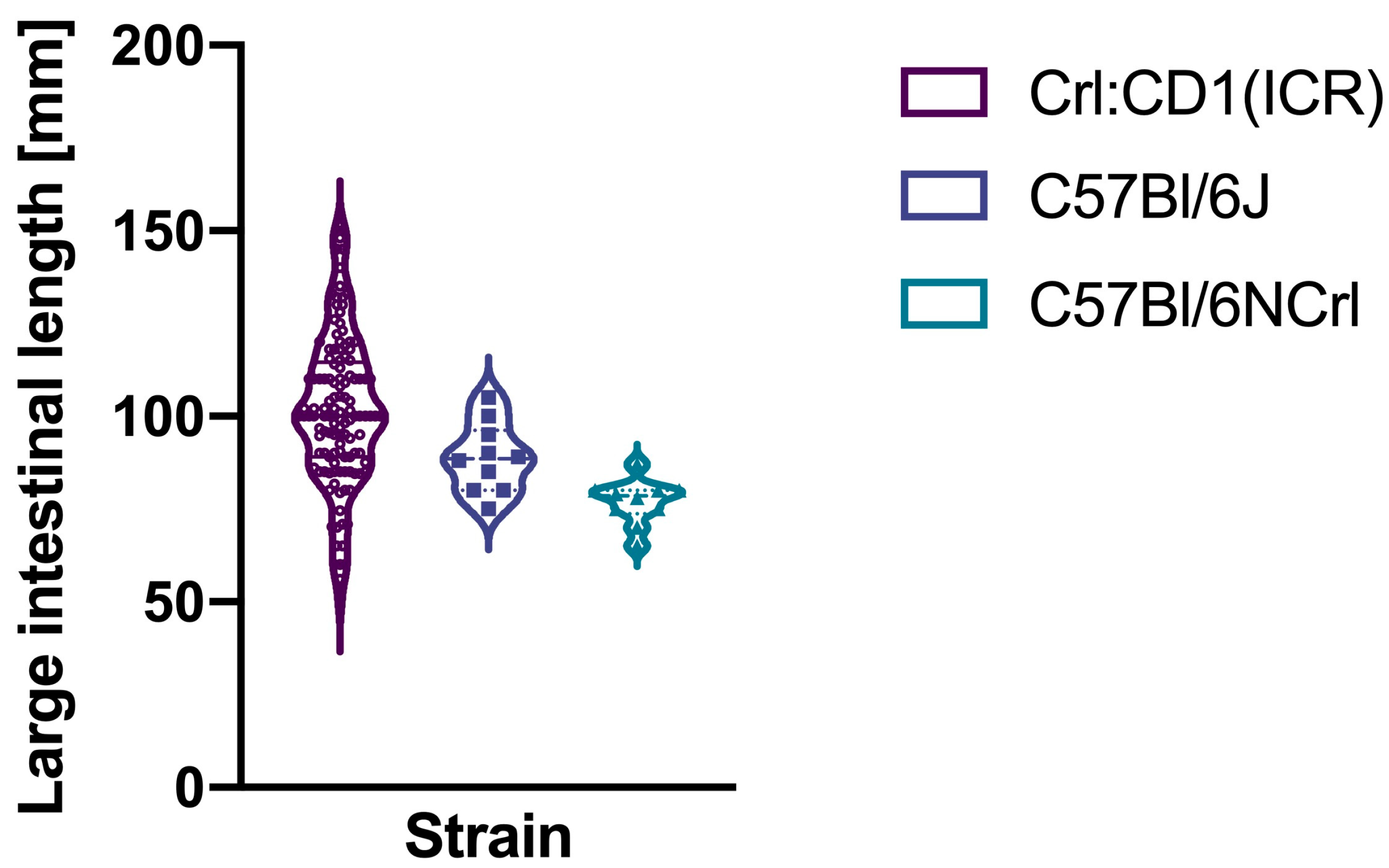

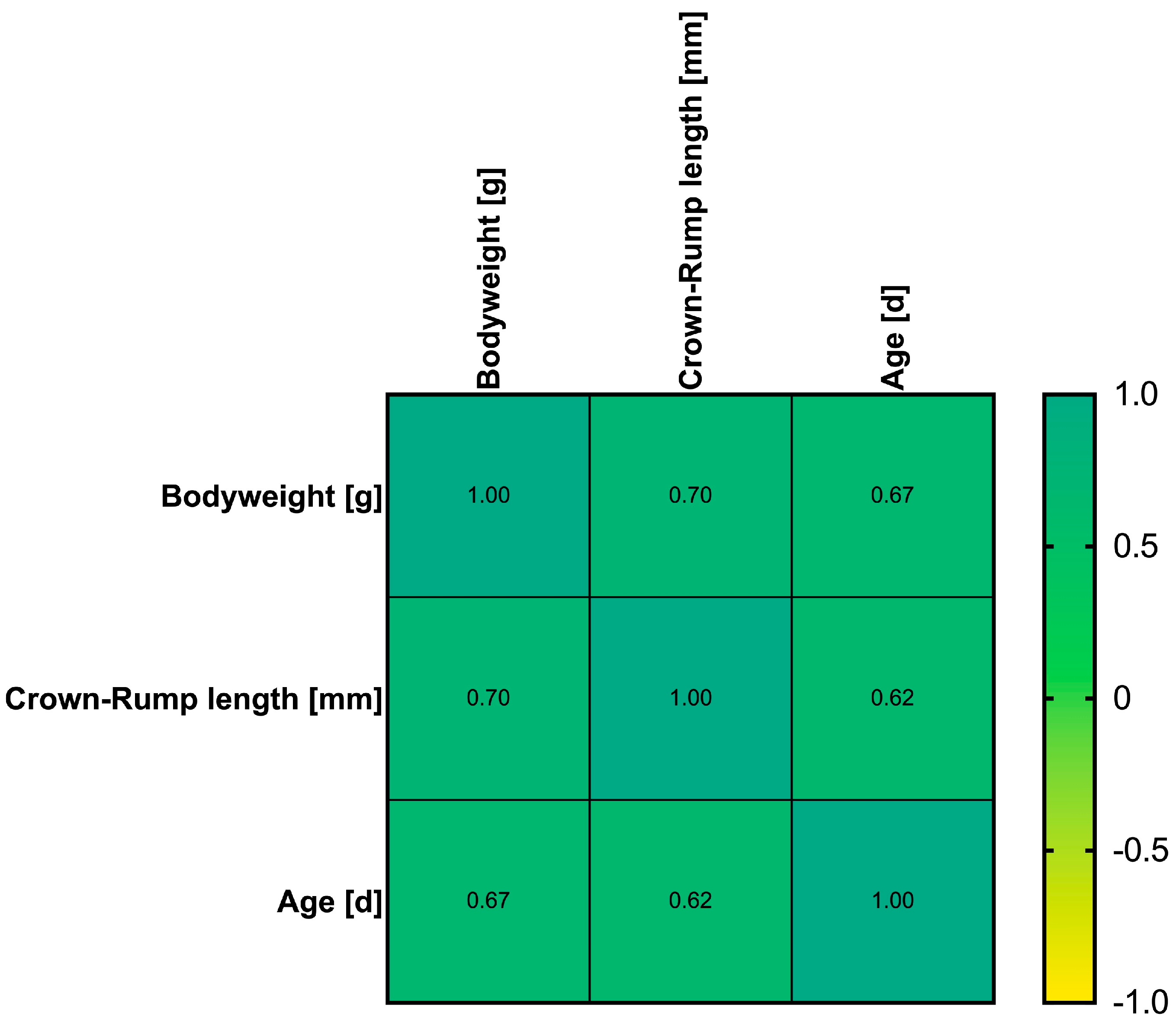

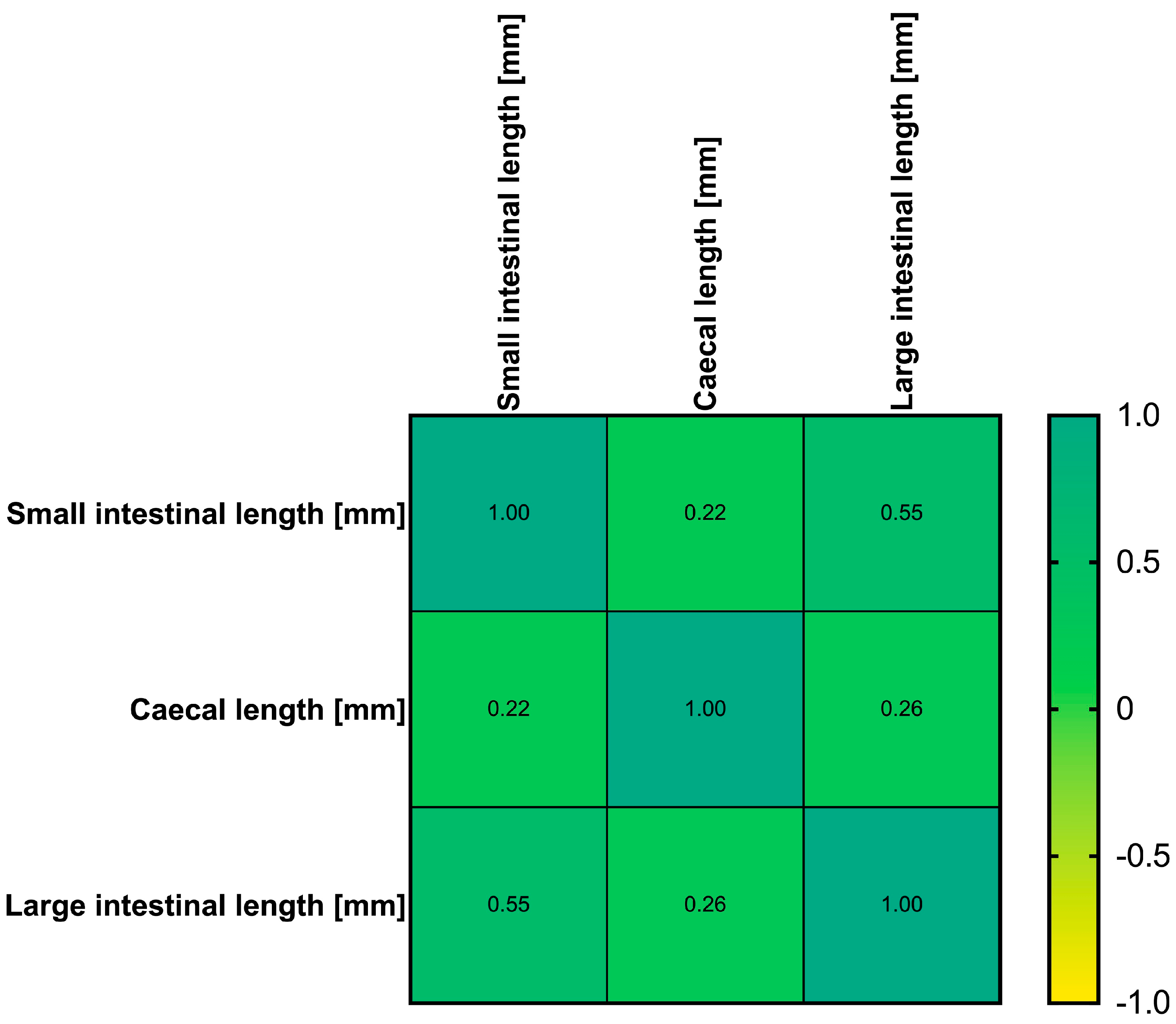

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Venara, A.; Meillat, H.; Cotte, E.; Ouaissi, M.; Duchalais, E.; Mor-Martinez, C.; Wolthuis, A.; Regimbeau, J.M.; Ostermann, S.; Hamel, J.F.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors for Severity of Postoperative Ileus After Colorectal Surgery: A Prospective Registry Data Analysis. World J. Surg. 2020, 44, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animaw, F.C.; Asresie, M.B.; Endeshaw, A.S. Postoperative Ileus and Associated Factors in Patients Following Major Abdominal Surgery in Ethiopia: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Yang, Y.; Guan, W.; Jin, G.; Yang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Excess Hospital Length of Stay and Extra Cost Attributable to Primary Prolonged Postoperative Ileus in Open Alimentary Tract Surgery: A Multicenter Cohort Analysis in China. Perioper. Med. 2024, 13, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traeger, L.; Koullouros, M.; Bedrikovetski, S.; Kroon, H.M.; Moore, J.W.; Sammour, T. Global Cost of Postoperative Ileus Following Abdominal Surgery: Meta-Analysis. BJS Open 2023, 7, zrad054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilz, T.O.; Stoffels, B.; Straßburg, C.; Schild, H.H.; Kalff, J.C. Ileus in Adults. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 508–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilz, T.; Wehner, S.; Pantelis, D.; Kalff, J. Immunmodulatorische Aspekte bei der Entstehung, Prophylaxe und Therapie des postoperativen Ileus. Zentralbl Chir. 2013, 139, 434–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, N.P.; Schneider, R.; Wehner, S.; Kalff, J.C.; Vilz, T.O. State-of-the-Art Colorectal Disease: Postoperative Ileus. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.; Lysson, M.; Schumak, B.; Vilz, T.; Specht, S.; Heesemann, J.; Roers, A.; Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. Leukocyte-Derived Interleukin-10 Aggravates Postoperative Ileus. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.; Hieggelke, L.; Schneiker, B.; Lysson, M.; Stoffels, B.; Nuding, S.; Wehkamp, J.; Kikhney, J.; Moter, A.; Kalff, J.C.; et al. Intestinal Manipulation Affects Mucosal Antimicrobial Defense in a Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupa, K.J.; Stein, K.; Schneider, R.; Lysson, M.; Schneiker, B.; Hornung, V.; Latz, E.; Iwakura, Y.; Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. AIM2 Inflammasome-Derived IL-1β Induces Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderes, J.; Mallesh, S.; Schneider, R.; Hupa, K.J.; Lysson, M.; Schneiker, B.; Händler, K.; Schlotmann, B.; Günther, P.; Schultze, J.L.; et al. A Population of Radio-Resistant Macrophages in the Deep Myenteric Plexus Contributes to Postoperative Ileus Via Toll-Like Receptor 3 Signaling. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 581111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilz, T.O.; Roessel, L.; Chang, J.; Pantelis, D.; Schwandt, T.; Koscielny, A.; Wehner, S.; Kalff, J.C. Establishing a Biomarker for Postoperative Ileus in Humans—Results of the BiPOI Trial. Life Sci. 2015, 143, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, S.; Oh, S.; Jung, J.E.; Kwon, I.G.; Noh, S.H. A Randomized Controlled Study to Assess the Effect of Mosapride Citrate on Intestinal Recovery Following Gastrectomy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Liu, B.; Huang, S.; Shi, W.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Bu, F. Postoperative Ileus Murine Model. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 209, 66465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilz, T.O.; Overhaus, M.; Stoffels, B.; Websky Mv Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. Functional Assessment of Intestinal Motility and Gut Wall Inflammation in Rodents: Analyses in a Standardized Model of Intestinal Manipulation. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, 67, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.A.; Türler, A.; Pezzone, M.A.; Dyer, K.; Grandis, J.; Bauer, A.J. Tyrphostin AG 126 Inhibits Development of Postoperative Ileus Induced by Surgical Manipulation of Murine Colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2004, 286, G214–G224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bree, S.H.; Nemethova, A.; van Bovenkamp, F.S.; Gomez-Pinilla, P.; Elbers, L.; Di Giovangiulio, M.; Matteoli, G.; van Vliet, J.; Cailotto, C.; Tanck, M.W.; et al. Novel Method for Studying Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 4, 219–227. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, H.; Yamazaki, T.; Mihara, T.; Kaji, N.; Kishi, K.; Hori, M. Purinergic P2X7 Receptor Antagonist Ameliorates Intestinal Inflammation in Postoperative Ileus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2022, 84, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, W.J.; Van Den Wijngaard, R.M.; The, F.O.; Ter Beek, M.-L.; Bennink, R.J.; Tytgat, G.N.J.; Buijs, R.M.; Reitsma, P.H.; Van Deventer, S.J.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Postoperative Ileus Is Maintained by Intestinal Immune Infiltrates That Activate Inhibitory Neural Pathways in Mice. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, W.J.; The, F.O.; Van Der Coelen, D.; Bennink, R.J.; Reitsma, P.H.; Van Deventer, S.J.; van den Wijngaard, R.M.; Boeckxstaens, G.E. Mast Cell Degranulation during Abdominal Surgery Initiates Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Gastroenterology 2004, 127, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, T.; Fink, M.; Cruz, R.J. Ethacrynic Acid Decreases Expression of Proinflammatory Intestinal Wall Cytokines and Ameliorates Gastrointestinal Stasis in Murine Postoperative Ileus. Clinics 2018, 73, e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.A.; Overhaus, M.; Whitcomb, J.; Ifedigbo, E.; Choi, A.M.K.; Otterbein, L.E.; Bauer, A.J. Brief Inhalation of Low-Dose Carbon Monoxide Protects Rodents and Swine from Postoperative Ileus. Crit. Care Med. 2005, 33, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stakenborg, N.; Wolthuis, A.M.; Gomez-Pinilla, P.J.; Farro, G.; Di Giovangiulio, M.; Bosmans, G.; Labeeuw, E.; Verhaegen, M.; Depoortere, I.; D’Hoore, A.; et al. Abdominal Vagus Nerve Stimulation as a New Therapeutic Approach to Prevent Postoperative Ileus. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilz, T.O.; Sommer, N.; Kahl, P.; Pantelis, D.; Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. Oral CPSI-2364 Treatment Prevents Postoperative Ileus in Swine without Impairment of Anastomotic Healing. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 32, 1362–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilz, T.O.; Pantelis, D.; Lingohr, P.; Fimmers, R.; Esmann, A.; Randau, T.; Kalff, J.C.; Coenen, M.; Wehner, S. SmartPill® as an Objective Parameter for Determination of Severity and Duration of Postoperative Ileus: Study Protocol of a Prospective, Two-Arm, Open-Label Trial (the PIDuSA Study). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Beekum, C.J.; Esmann, A.; Heinze, F.; von Websky, M.W.; Stoffels, B.; Wehner, S.; Coenen, M.; Fimmers, R.; Randau, T.M.; Kalff, J.C.; et al. Safety and Suitability of the SmartPill® after Abdominal Surgery: Results of the Prospective, Two-Armed, Open-Label PIDuSA Trial. Eur. Surg. Res. 2021, 62, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martensen, A.K.; Moen, E.V.; Brock, C.; Funder, J.A. Postoperative Ileus—Establishing a Porcine Model. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2024, 36, e14872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Chen, W.; Dai, J.; Mo, P.; Yu, C.; Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Zhuo, R.; Su, G. Steroid Receptor Coactivator-3 Is Required for Inhibition of the Intestinal Muscularis Inflammatory Response of Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Inflammation 2021, 44, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Winter, B.Y.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; De Man, J.G.; Moreels, T.G.; Herman, A.G.; Pelckmans, P.A. Effect of Adrenergic and Nitrergic Blockade on Experimental Ileus in Rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997, 120, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, E.J.; Yoon, Y.H.; Park, H. The Effects of Prucalopride on Postoperative Ileus in Guinea Pigs. Yonsei Med. J. 2013, 54, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, S.; Behrendt, F.F.; Lyutenski, B.N.; Lysson, M.; Bauer, A.J.; Hirner, A.; Kalff, J.C. Inhibition of Macrophage Function Prevents Intestinal Inflammation and Postoperative Ileus in Rodents. Gut 2007, 56, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehner, S.; Straesser, S.; Vilz, T.O.; Pantelis, D.; Sielecki, T.; De La Cruz, V.F.; Hirner, A.; Kalff, J.C. Inhibition of P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway as Prophylaxis of Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, T.; Chi, P. Inhibition of MK2 Shows Promise for Preventing Postoperative Ileus in Mice. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 185, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehner, S.; Meder, K.; Vilz, T.O.; Alteheld, B.; Stehle, P.; Pech, T.; Kalff, J.C. Preoperative Short-Term Parenteral Administration of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids Ameliorates Intestinal Inflammation and Postoperative Ileus in Rodents. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2012, 397, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breßer, M.; Siemens, K.D.; Schneider, L.; Lunnebach, J.E.; Leven, P.; Glowka, T.R.; Oberländer, K.; De Domenico, E.; Schultze, J.L.; Schmidt, J.; et al. Macrophage-Induced Enteric Neurodegeneration Leads to Motility Impairment during Gut Inflammation. EMBO Mol. Med. 2025, 17, 301–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leven, P.; Schneider, R.; Schneider, L.; Mallesh, S.; Vanden Berghe, P.; Sasse, P.; Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. β-Adrenergic Signaling Triggers Enteric Glial Reactivity and Acute Enteric Gliosis during Surgery. J. Neuroinflammation 2023, 20, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffels, B.; Hupa, K.J.; Snoek, S.A.; Van Bree, S.; Stein, K.; Schwandt, T.; Vilz, T.O.; Lysson, M.; Veer, C.V.; Kummer, M.P.; et al. Postoperative Ileus Involves Interleukin-1 Receptor Signaling in Enteric Glia. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfar, W.; Gurjar, A.A.; Talukder, M.A.H.; Noble, M.; Di Lorenzo, C.; Elfar, J. Erythropoietin Promotes Functional Recovery in a Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 33, e14049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, H.; Hong, Z.; Chi, P. Inhibition of JAK1 Mitigates Postoperative Ileus in Mice. Surgery 2019, 166, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, K.; Stoffels, M.; Lysson, M.; Schneiker, B.; Dewald, O.; Krönke, G.; Kalff, J.C.; Wehner, S. A Role for 12/15-Lipoxygenase-Derived Proresolving Mediators in Postoperative Ileus: Protectin DX-Regulated Neutrophil Extravasation. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2016, 99, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, Y.; Koike, K.; Chiba, H.; Mitamura, A.; Tsuji, H.; Kawasaki, S.; Yokota, T.; Kanemasa, T.; Morioka, Y.; Suzuki, T.; et al. Efficacy of Naldemedine on Intestinal Hypomotility and Adhesions in Rodent Models of Postoperative Ileus. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 46, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, L.M.M.; Van Der Vliet, J.; Van Bree, S.H.W.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; Cailotto, C. Endogenous Vagal Activation Dampens Intestinal Inflammation Independently of Splenic Innervation in Postoperative Ileus. Auton. Neurosci. 2014, 185, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, L.M.M.; Van Der Vliet, J.; Farro, G.; Matteoli, G.; Van Bree, S.H.W.; Olivier, B.J.; Nolte, M.A.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; Cailotto, C. The Spleen Responds to Intestinal Manipulation but Does Not Participate in the Inflammatory Response in a Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Xu, M.; Shi, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Shi, Y.; Xu, X.; Shao, T.; Sun, Q. Shenhuang Plaster Ameliorates the Inflammation of Postoperative Ileus through Inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB Pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firpo, M.A.; Rollins, M.D.; Szabo, A.; Gull, J.D.; Jackson, J.D.; Shao, Y.; Glasgow, R.E.; Mulvihill, S.J. A Conscious Mouse Model of Gastric Ileus Using Clinically Relevant Endpoints. BMC Gastroenterol. 2005, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehner, S.; Schwarz, N.T.; Hundsdoerfer, R.; Hierholzer, C.; Tweardy, D.J.; Billiar, T.R.; Bauer, A.J.; Kalff, J.C. Induction of IL-6 within the Rodent Intestinal Muscularis after Intestinal Surgical Stress. Surgery 2005, 137, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festing, M.F.W. Evidence Should Trump Intuition by Preferring Inbred Strains to Outbred Stocks in Preclinical Research. ILAR J. 2014, 55, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festing, M.F.W. Properties of Inbred Strains and Outbred Stocks, with Special Reference to Toxicity Testing. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 1979, 5, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festing, M.F.W. Inbred Strains Should Replace Outbred Stocks in Toxicology, Safety Testing, and Drug Development. Toxicol. Pathol. 2010, 38, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, A.H.; Philip, V.M.; Chesler, E.J.; Mogil, J.S. Comparing Phenotypic Variation between Inbred and Outbred Mice. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 994–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.J.; Simpson, E.M.; Takahashi, J.S.; Lipp, H.-P.; Nakanishi, S.; Wehner, J.M.; Giese, K.P.; Tully, T.; Abel, T.; Chapman, P.F.; et al. Mutant Mice and Neuroscience: Recommendations Concerning Genetic Background. Neuron 1997, 19, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Ruiven, R.; Meijer, G.W.; Van Zutphen, L.F.M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, J. Adaptation Period of Laboratory Animals after Transport: A Review. Scand. J. Lab. Anim. Sci. 1996, 23, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obernier, J.A.; Baldwin, R.L. Establishing an Appropriate Period of Acclimatization Following Transportation of Laboratory Animals. ILAR J. 2006, 47, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Kortzfleisch, V.T.; Karp, N.A.; Palme, R.; Kaiser, S.; Sachser, N.; Richter, S.H. Improving Reproducibility in Animal Research by Splitting the Study Population into Several ‘Mini-Experiments’. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C.; Tagkalos, E.; Lindner, A.; Baumgart, N.; Gruber, G.; Baumgart, J.; Lang, H.; Heimann, A.; Muensterer, O.J. Bodyweight, Not Age, Determines Oesophageal Length and Breaking Strength in Rats. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 54, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C.; Tagkalos, E.; Lindner, A.; Lang, H.; Heimann, A.; Schröder, A.; Grimminger, P.P.; Muensterer, O.J. Esophageal Biomechanics Revisited: A Tale of Tenacity, Anastomoses, and Suture Bite Lengths in Swine. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2019, 107, 1670–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratz, T.; Dauvergne, J.; Kronberg, A.-S.; Katzer, D.; Ganschow, R.; Bernhardt, M.; Westeppe, S.; Bierbach, B.; Strohm, J.; Oetzmann Von Sochaczewski, C. Not All Porcine Intestinal Segments Are Equal in Terms of Breaking Force, but None Were Associated to Allometric Parameters. Gastroenterol. Insights 2023, 14, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginghina, R.C.; Kronberg, A.-S.; Dauvergne, J.; Kratz, T.; Katzer, D.; Ganschow, R.; Bernhardt, M.; Westeppe, S.; Vilz, T.O.; Bierbach, B.; et al. Anatomical Parameters Do Not Determine Linear Breaking Strength or Dimensions of the Porcine Biliary System. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2024, 48, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuting, P.M.; Snyder, J.M. Mouse Necropsy. Curr. Protoc. Mouse Biol. 2015, 5, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudamore, C.L.; Busk, N.; Vowell, K. A Simplified Necropsy Technique for Mice: Making the Most of Unscheduled Deaths. Lab. Anim. 2014, 48, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, K.; Kuch, B.; Dengler, S.; Demir, I.E.; Zeller, F.; Schemann, M. How Big Is the Little Brain in the Gut? Neuronal Numbers in the Enteric Nervous System of Mice, Guinea Pig, and Human. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 34, e14440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabella, G. The Number of Neurons in the Small Intestine of Mice, Guinea-Pigs and Sheep. Neuroscience 1987, 22, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuber, M.; Lindner, A.; Baumgart, J.; Baumgart, N.; Heimann, A.; Schröder, A.; Muensterer, O.J.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. Sex Represents a Relevant Interaction in Sprague–Dawley Rats: The Example of Oesophageal Length. All Life 2020, 13, 448–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwick, B.; Krishnamoorthy, K. Cvequality: Tests for the Equality of Coefficients of Variation from Multiple Groups 2019, 0.2.0; The Comprehensive R Archive Network, CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2019; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, K. MBESS: The MBESS R Package, 4.9.41; The Comprehensive R Archive Network, CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Heydweiller, A.; Kurz, R.; Schröder, A.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. Inguinal Hernia Repair in Inpatient Children: A Nationwide Analysis of German Administrative Data. BMC Surg. 2021, 21, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C.; Gödeke, J. Pilonidal Sinus Disease on the Rise: A One-Third Incidence Increase in Inpatients in 13 Years with Substantial Regional Variation in Germany. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydweiller, A.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. The Epidemiology of Funnel Chest Repairs in Germany: Monitoring the Success of Nuss’ Procedure. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2022, 30, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, K.; Lee, M. Improved Tests for the Equality of Normal Coefficients of Variation. Comput Stat 2014, 29, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassambara, A. Rstatix: Pipe-Friendly Framework for Basic Statistical Tests, 0.7.3.; The Comprehensive R Archive Network, CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, A.; Tagkalos, E.; Heimann, A.; Nuber, M.; Baumgart, J.; Baumgart, N.; Muensterer, O.J.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. Tracheal Bifurcation Located at Proximal Third of Oesophageal Length in Sprague Dawley Rats of All Ages. Scand. J. Lab. Anim. Sci. 2020, 46, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.; Leven, P.; Mallesh, S.; Breßer, M.; Schneider, L.; Mazzotta, E.; Fadda, P.; Glowka, T.; Vilz, T.O.; Lingohr, P.; et al. IL-1-Dependent Enteric Gliosis Guides Intestinal Inflammation and Dysmotility and Modulates Macrophage Function. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Cassissi, C.; Drexler, P.G.; Vogel, S.B.; Sninsky, C.A.; Hocking, M.P. Salsalate, Morphine, and Postoperative Ileus. Am. J. Surg. 1996, 171, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witjes, V.M.; Boleij, A.; Halffman, W. Reducing versus Embracing Variation as Strategies for Reproducibility: The Microbiome of Laboratory Mice. Animals 2020, 10, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Kortzfleisch, V.T.; Ambrée, O.; Karp, N.A.; Meyer, N.; Novak, J.; Palme, R.; Rosso, M.; Touma, C.; Würbel, H.; Kaiser, S.; et al. Do Multiple Experimenters Improve the Reproducibility of Animal Studies? PLoS Biol. 2022, 20, e3001564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, E.J. Results of Growth Curve Analyses in Mice and Rats. J. Anim. Sci. 1976, 42, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeffner, D.J.; Warren, D.A.; Muralidara, S.; Bruckner, J.V.; Simmons, J.E. Organ Weights and Fat Volume In Rats as a Function of Strain And Age. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 1999, 56, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, D.J. Age-Specific Absolute and Relative Organ Weight Distributions For B6C3F1 Mice. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2012, 75, 76–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struijs, M.-C.; Diamond, I.R.; De Silva, N.; Wales, P.W. Establishing Norms for Intestinal Length in Children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2009, 44, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacchino, R.M. Bowel Length: Measurement, Predictors, and Impact on Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2015, 11, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, V.S.; Porsgaard, T.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Hvid, H. Rodent Model Choice Has Major Impact on Variability of Standard Preclinical Readouts Associated with Diabetes and Obesity Research. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2016, 8, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar]

- Aigner, B. Variability of Test Parameters from Mice of Different Age Groups in Published Data Sets. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, E.J.; Lang, B.J.; Legates, J.E. Comparison of Growth Functions within and between Lines of Mice Selected for Large and Small Body Weight. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1969, 39, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.N.; Haseman, J.K.; Grumbein, S.; Crawford, D.D.; Eustis, S.L. Growth, Body Weight, Survival, and Tumor Trends in (C57BL/6 X C3H/HeN) F1 (B6C3F1) Mice during a Nine-Year Period. Toxicol. Pathol. 1990, 18, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.C.; Bakker, H. The Effects of Selection for Different Combinations of Weights at Two Ages on the Growth Curve of Mice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1979, 55, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, J.M.; Aspden, R.M.; Armour, K.E.; Armour, K.J.; Reid, D.M. Growth of C57Bl/6 Mice and the Material and Mechanical Properties of Cortical Bone from the Tibia. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2004, 74, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kachman, S.D.; Baker, R.L.; Gianola, D. Phenotypic and Genetic Variability of Estimated Growth Curve Parameters in Mice. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1988, 76, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, G.A.E.; Kyle, W.H. Growth of the Laboratory Mouse. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1968, 38, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, D.R.; Koscielny, A.; Wehner, S.; Maurer, J.; Schiwon, M.; Franken, L.; Schumak, B.; Limmer, A.; Sparwasser, T.; Hirner, A.; et al. T Helper Type 1 Memory Cells Disseminate Postoperative Ileus over the Entire Intestinal Tract. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 1407–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Vargas, O.; Brass, A.; Karystianis, G.; Bramhall, M.; Stevens, R.; Cruickshank, S.; Nenadic, G. Bias in the Reporting of Sex and Age in Biomedical Research on Mouse Models. eLife 2016, 5, e13615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karp, N.A.; Reavey, N. Sex Bias in Preclinical Research and an Exploration of How to Change the Status Quo. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 4107–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, J.; LaLiberté, C.; Van Eede, M.; Lerch, J.P.; Henkelman, M. Variability of Brain Anatomy for Three Common Mouse Strains. NeuroImage 2016, 142, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, K. Sample Size Planning for the Coefficient of Variation from the Accuracy in Parameter Estimation Approach. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, A.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. On the Difference between A-Priori and Observed Statistical Power—A Comment on “Statistical Power and Sample Size Calculations: A Primer for Pediatric Surgeons”. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 203–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcin, B.; Katarzyna, S.-A.; Ivan, K. The Role of Beta-Adrenoreceptors in Postoperative Ileus in Rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 4851–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, R.; Thevenin, J.; Planchamp, T.; Berthon, T.; Rousset, P.; Wang, S.; Canivet, A.; Knauf, C.; Vergnolle, N.; Buscail, E.; et al. Modeling Postoperative Pathologic Ileus in Mice: A Simplified and Translational Approach. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2025, 37, e70157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

von Stumberg, M.; Akinci, E.; Ertim, B.; Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. Shortcoming of the Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus: Small Intestinal Lengths Have Similar Variations in In- and Outbred Mice and Cannot Be Predicted by Allometric Parameters. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122948

von Stumberg M, Akinci E, Ertim B, Oetzmann von Sochaczewski C. Shortcoming of the Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus: Small Intestinal Lengths Have Similar Variations in In- and Outbred Mice and Cannot Be Predicted by Allometric Parameters. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122948

Chicago/Turabian Stylevon Stumberg, Maximiliane, Ejder Akinci, Berkan Ertim, and Christina Oetzmann von Sochaczewski. 2025. "Shortcoming of the Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus: Small Intestinal Lengths Have Similar Variations in In- and Outbred Mice and Cannot Be Predicted by Allometric Parameters" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122948

APA Stylevon Stumberg, M., Akinci, E., Ertim, B., & Oetzmann von Sochaczewski, C. (2025). Shortcoming of the Mouse Model of Postoperative Ileus: Small Intestinal Lengths Have Similar Variations in In- and Outbred Mice and Cannot Be Predicted by Allometric Parameters. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2948. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122948