Thykamine™: A New Player in the Field of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Abstract

1. Introduction

| Characteristic | MCP-1 | MIP-1α | MIP-1β | RANTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main receptors | ||||

| CCR1 | ✓ [4] | ✓ [6] | ||

| CCR2 | ✓ [3] | |||

| CCR3 | ✓ [6] | |||

| CCR5 | ✓ [4] | ✓ [5] | ✓ [6] | |

| Associated immune cell types | ||||

| Monocytes | ✓ [12] | ✓ [13] | ✓ [14] | ✓ [15] |

| Neutrophils | ✓ [16] | ✓ [16] | ✓ [14] | ✓ [17] |

| CD4+, CD8+, and NK T lymphocytes | ✓ [18,19] | ✓ [18,20] | ✓ [18,19,21] | ✓ [18,19] |

| Dendritic cells | ✓ [22] | ✓ [23] | ✓ [23] | ✓ [24] |

| Eosinophils | ✓ [25] | ✓ [26] | ✓ [27] | ✓ [26] |

| Disease | Sample Type | Reference | MCP-1 | MIP-1α | MIP-1β | RANTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Serum | [28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Psoriatic arthritis | Serum | [10,29] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Osteoarthritis | Synovial fluid | [13,30,31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Atopic dermatitis | Serum | [32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Asthma | Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid | [33] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease) | Intestinal mucosa | [34,35] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Osteoporosis | Serum | [36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Metabolic-dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) | Plasma/serum | [37,38] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Systemic sclerosis | Serum | [39,40] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Serum | [41] | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Severe COVID-19 | Serum | [42] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Experimental Design

2.2. Cytokine Quantification

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

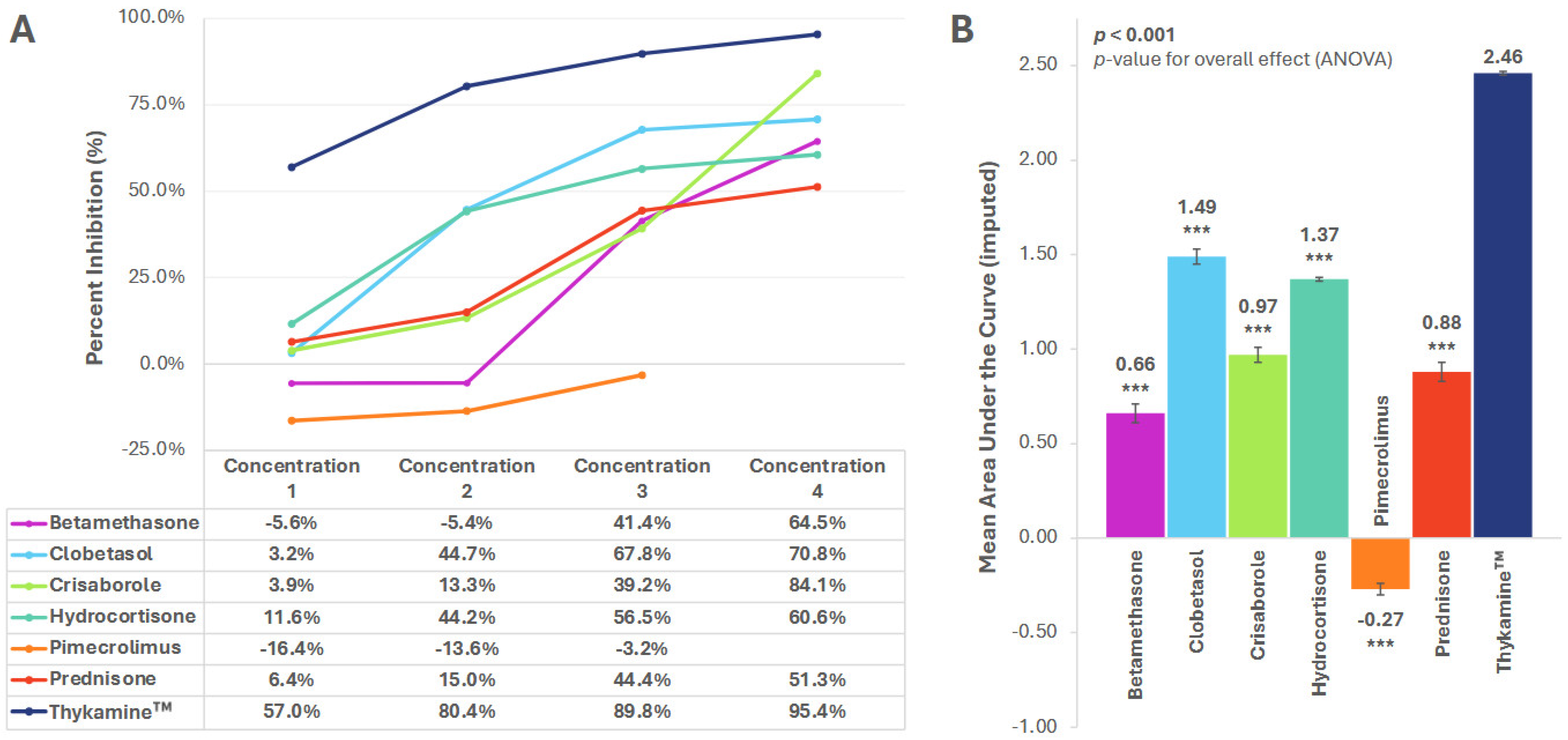

3.1. MCP-1

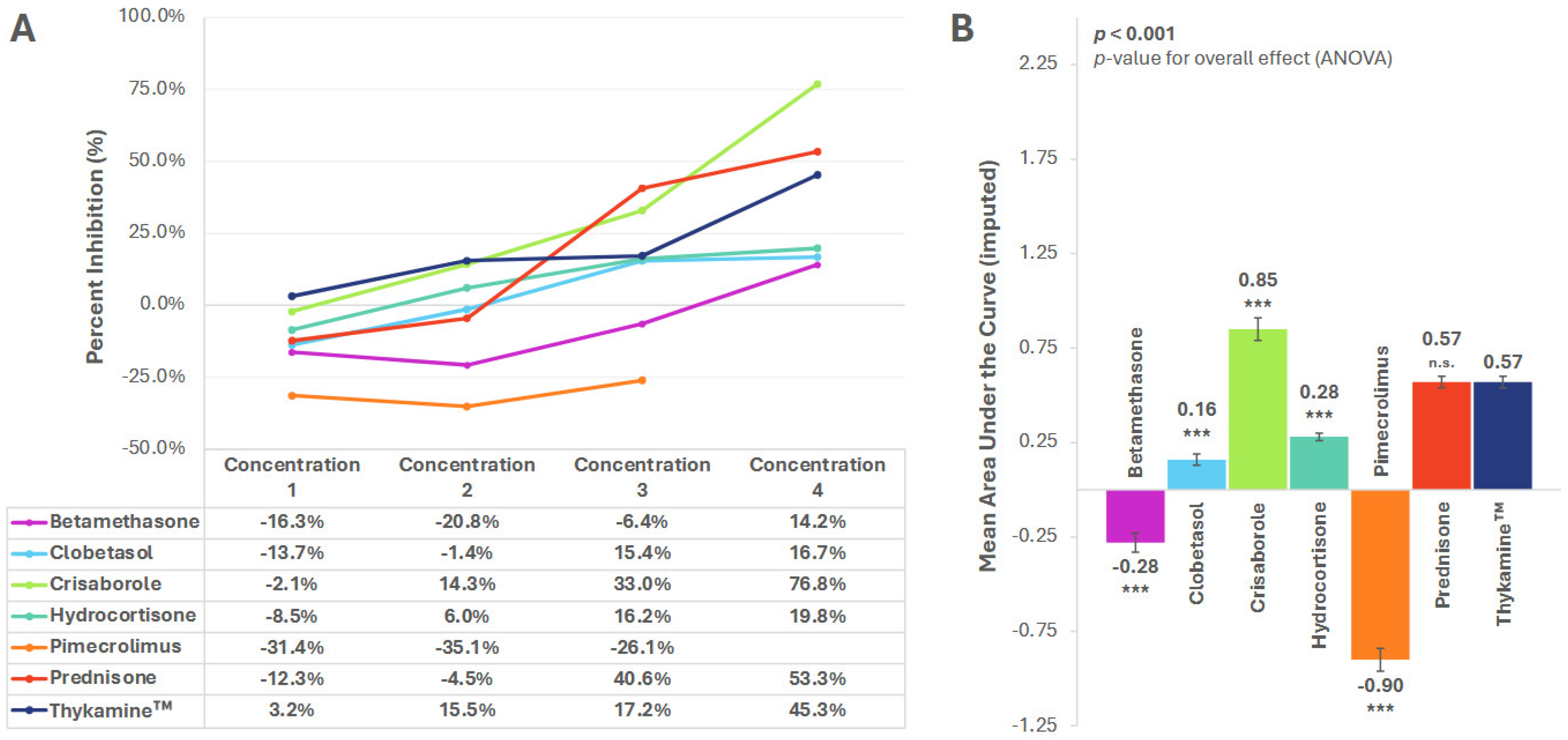

3.2. MIP-1α and MIP-1β

3.3. RANTES

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| CA | California |

| CCL | C-C Chemokine Ligand |

| CCR | C-C Chemokine Receptor |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019m |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MCP-1 | Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 |

| MIP-1α | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 alpha |

| MIP-1β | Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 beta |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-Light-Chain-Enhancer of Activated B Cells |

| ON | Ontario |

| PAMP | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| RANTES | Regulated on Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Secreted |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptor |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| USA | United States of America |

| VA | Virginia |

| YB | Y-Box |

References

- Mazgaeen, L.; Gurung, P. Recent Advances in Lipopolysaccharide Recognition Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, K.; Dixit, V.M. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a006049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Anshita, D.; Ravichandiran, V. MCP-1: Function, regulation, and involvement in disease. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 101, 107598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavsar, I.; Miller, C.S.; Al-Sabbagh, M. Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1 Alpha (MIP-1 alpha)/CCL3: As a Biomarker. In General Methods in Biomarker Research and Their Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mukaida, N.; Sasaki, S.I.; Baba, T. CCL4 Signaling in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1231, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Lan, T.; Wei, Y.; Wei, X. CCL5/CCR5 axis in human diseases and related treatments. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Beller, D.I.; Frendl, G.; Graves, D.T. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production in human monocytes. J. Immunol. 1992, 148, 2423–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, H.; Varsos, Z.S.; Sud, S.; Craig, M.J.; Ying, C.; Pienta, K.J. CCL2 and interleukin-6 promote survival of human CD11b+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells and induce M2-type macrophage polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 34342–34354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumark, E.; Sagi-Assif, O.; Shalmon, B.; Ben-Baruch, A.; Witz, I.P. Progression of mouse mammary tumors: MCP-1-TNFalpha cross-regulatory pathway and clonal expression of promalignancy and antimalignancy factors. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 106, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purzycka-Bohdan, D.; Nedoszytko, B.; Zabłotna, M.; Gleń, J.; Szczerkowska-Dobosz, A.; Nowicki, R.J. Chemokine Profile in Psoriasis Patients in Correlation with Disease Severity and Pruritus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Zhu, N.; Mao, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, L.; Wu, B. Expression levels of CXCR4 and CXCL12 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and its correlation with disease activity. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 20, 1925–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Kitamura, T.; Zhang, J.; Campion, L.R.; Kaiser, E.A.; Snyder, L.A.; Pollard, J.W. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature 2011, 475, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Gu, M.; Xu, X.; Wen, X.; Yang, G.; Li, L.; Sheng, P.; Meng, F. CCL3/CCR1 mediates CD14(+)CD16(−) circulating monocyte recruitment in knee osteoarthritis progression. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2020, 28, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Kochumon, S.; Shenouda, S.; Wilson, A.; Al-Mulla, F.; Ahmad, R. The Cooperative Induction of CCL4 in Human Monocytic Cells by TNF-α and Palmitate Requires MyD88 and Involves MAPK/NF-κB Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schall, T.J.; Bacon, K.; Toy, K.J.; Goeddel, D.V. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature 1990, 347, 669–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, C.A.; Rehberg, M.; Lerchenberger, M.; Berberich, N.; Bihari, P.; Khandoga, A.G.; Zahler, S.; Krombach, F. CCL2 and CCL3 mediate neutrophil recruitment via induction of protein synthesis and generation of lipid mediators. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwaiz, R.; Rahman, M.; Syk, I.; Zhang, E.; Thorlacius, H. Rac1-dependent secretion of platelet-derived CCL5 regulates neutrophil recruitment via activation of alveolar macrophages in septic lung injury. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 97, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loetscher, P.; Seitz, M.; Clark-Lewis, I.; Baggiolini, M.; Moser, B. Monocyte chemotactic proteins MCP-1, MCP-2, and MCP-3 are major attractants for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes. FASEB J. 1994, 8, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loetscher, P.; Seitz, M.; Clark-Lewis, I.; Baggiolini, M.; Moser, B. Activation of NK cells by CC chemokines. Chemotaxis, Ca2+ mobilization, and enzyme release. J. Immunol. 1996, 156, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, F.; Bobanga, I.D.; Rauhe, P.; Barkauskas, D.; Teich, N.; Tong, C.; Myers, J.; Huang, A.Y. CCL3 augments tumor rejection and enhances CD8(+) T cell infiltration through NK and CD103(+) dendritic cell recruitment via IFNγ. Oncoimmunology 2018, 7, e1393598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystry, R.S.; Aluvihare, V.; Welch, K.A.; Kallikourdis, M.; Betz, A.G. B cells and professional APCs recruit regulatory T cells via CCL4. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, D.; Lamontagne, A.; Foss, C.A.; Khan, Z.K.; Pomper, M.G.; Jain, P. Dendritic cell CNS recruitment correlates with disease severity in EAE via CCL2 chemotaxis at the blood-brain barrier through paracellular transmigration and ERK activation. J. Neuroinflamm. 2012, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Vassiliou, E.; Ganea, D. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits production of the inflammatory chemokines CCL3 and CCL4 in dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003, 74, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttcher, J.P.; Bonavita, E.; Chakravarty, P.; Blees, H.; Cabeza-Cabrerizo, M.; Sammicheli, S.; Rogers, N.C.; Sahai, E.; Zelenay, S.; Reis e Sousa, C. NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 2018, 172, 1022–1037.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izumi, S.; Hirai, K.; Miyamasu, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Misaki, Y.; Takaishi, T.; Morita, Y.; Matsushima, K.; Ida, N.; Nakamura, H.; et al. Expression and regulation of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human eosinophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 1997, 27, 816–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukacs, N.W.; Standiford, T.J.; Chensue, S.W.; Kunkel, R.G.; Strieter, R.M.; Kunkel, S.L. C-C chemokine-induced eosinophil chemotaxis during allergic airway inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996, 60, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Konno, Y.; Ueki, S.; Tomoda, K.; Kanda, A. MIP-1β is associated with eosinophilic airway inflammation. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, PA934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucur, A.; Jajic, Z.; Artukovic, M.; Matijasevic, M.I.; Anic, B.; Flegar, D.; Markotic, A.; Kelava, T.; Ivcevic, S.; Kovacic, N.; et al. Chemokine signals are crucial for enhanced homing and differentiation of circulating osteoclast progenitor cells. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2017, 19, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szodoray, P.; Alex, P.; Chappell-Woodward, C.M.; Madland, T.M.; Knowlton, N.; Dozmorov, I.; Zeher, M.; Jarvis, J.N.; Nakken, B.; Brun, J.G.; et al. Circulating cytokines in Norwegian patients with psoriatic arthritis determined by a multiplex cytokine array system. Rheumatology 2006, 46, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allavena, P.; Bianchi, G.; Zhou, D.; van Damme, J.; Jílek, P.; Sozzani, S.; Mantovani, A. Induction of natural killer cell migration by monocyte chemotactic protein-1, -2 and -3. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994, 24, 3233–3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monibi, F.; Roller, B.L.; Stoker, A.; Garner, B.; Bal, S.; Cook, J.L. Identification of Synovial Fluid Biomarkers for Knee Osteoarthritis and Correlation with Radiographic Assessment. J. Knee Surg. 2016, 29, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaburagi, Y.; Shimada, Y.; Nagaoka, T.; Hasegawa, M.; Takehara, K.; Sato, S. Enhanced production of CC-chemokines (RANTES, MCP-1, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, and eotaxin) in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2001, 293, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, R.; York, J.; Boyars, M.; Stafford, S.; Grant, J.A.; Lee, J.; Forsythe, P.; Sim, T.; Ida, N. Increased MCP-1, RANTES, and MIP-1alpha in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of allergic asthmatic patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 153, 1398–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, G.; Moriarty, D.; O’Donoghue, D.P.; McCormick, P.A.; Sheahan, K.; Baird, A.W. Tissue cytokine and chemokine expression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Res. 2001, 50, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.; Bateman, A.; Payne, R.; Johnson, P.; Sheron, N. Chemokine expression in IBD. Mucosal chemokine expression is unselectively increased in both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J. Pathol. 2003, 199, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatehi, F.; Mollahosseini, M.; Hassanshahi, G.; Khanamani Falahati-Pour, S.; Khorramdelazad, H.; Ahmadi, Z.; Noroozi Karimabad, M.; Farahmand, H. CC chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CCL4 and CCL5 are elevated in osteoporosis patients. J. Biomed. Res. 2017, 31, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Chiwanda Kaminga, A.; Liu, A.; Wen, S.W.; Chen, J.; Luo, J. Chemokines in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounika, N.; Mungase, S.B.; Verma, S.; Kaur, S.; Deka, U.J.; Ghosh, T.S.; Adela, R. Inflammatory Protein Signatures as Predictive Disease-Specific Markers for Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Inflammation 2025, 48, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandinelli, F.; Del Rosso, A.; Gabrielli, A.; Giacomelli, R.; Bartoli, F.; Guiducci, S.; Matucci Cerinic, M. CCL2, CCL3 and CCL5 chemokines in systemic sclerosis: The correlation with SSc clinical features and the effect of prostaglandin E1 treatment. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2012, 30, S44–S49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, M.; Sato, S.; Takehara, K. Augmented production of chemokines (monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha (MIP-1alpha) and MIP-1beta) in patients with systemic sclerosis: MCP-1 and MIP-1alpha may be involved in the development of pulmonary fibrosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1999, 117, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilá, L.M.; Molina, M.J.; Mayor, A.M.; Cruz, J.J.; Ríos-Olivares, E.; Ríos, Z. Association of serum MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES with clinical manifestations, disease activity, and damage accrual in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin. Rheumatol. 2007, 26, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, Y.; Doré, É.; Dubuc, I.; Archambault, A.-S.; Flamand, O.; Laviolette, M.; Flamand, N.; Boilard, É.; Flamand, L. Chemokines and eicosanoids fuel the hyperinflammation within the lungs of patients with severe COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 148, 368–380.e363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, O.D.; Vidal, L.F.; Wilman, M.V.; Bultink, I.E.M.; Raterman, H.G.; Lems, W. Management of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2021, 33, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaboriboon, B.; Silverman, E.; Homsanit, M.; Chui, H.; Kaufman, M. Weight change associated with corticosteroid therapy in adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2012, 22, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waljee, A.K.; Rogers, M.A.M.; Lin, P.; Singal, A.G.; Stein, J.D.; Marks, R.M.; Ayanian, J.Z.; Nallamothu, B.K. Short term use of oral corticosteroids and related harms among adults in the United States: Population based cohort study. BMJ 2017, 357, j1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tijsseling, D.; ter Wolbeek, M.; Derks, J.B.; de Vries, W.B.; Heijnen, C.J.; van Bel, F.; Mulder, E.J.H. Neonatal corticosteroid therapy affects growth patterns in early infancy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.O.; Sieborg, J.; Nymand, L.K.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Ezzedine, K.; Schlapbach, C.; Molin, S.; Zhang, J.; Zachariae, C.; Thomsen, S.F.; et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of topical corticosteroid phobia among patients with chronic hand eczema-Findings from the Danish Skin Cohort. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, W.C.; Chenge, J.; Wang, J.; Girvan, H.M.; Yang, L.; Chai, S.C.; Huber, A.D.; Wu, J.; Oladimeji, P.O.; Munro, A.W.; et al. Clobetasol Propionate Is a Heme-Mediated Selective Inhibitor of Human Cytochrome P450 3A5. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1415–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decani, S.; Federighi, V.; Baruzzi, E.; Sardella, A.; Lodi, G. Iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome and topical steroid therapy: Case series and review of the literature. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2014, 25, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irakam, A.; Miskolci, V.; Vancurova, I.; Davidson, D. Dose-related inhibition of proinflammatory cytokine release from neutrophils of the newborn by dexamethasone, betamethasone, and hydrocortisone. Biol. Neonate 2002, 82, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wauwe, J.; Aerts, F.; Walter, H.; de Boer, M. Cytokine production by phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human blood cells: Effects of corticosteroids, T cell immunosuppressants and phosphodiesterase IV inhibitors. Inflamm. Res. 1995, 44, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, L.; Olin, B. Crisaborole: A Novel Nonsteroidal Topical Treatment for Atopic Dermatitis. J. Pharm. Technol. 2019, 35, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlo, S.; Kooijman, R.; Beck, I.M.; Kolmus, K.; Spooren, A.; Haegeman, G. Cyclic AMP: A selective modulator of NF-κB action. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2011, 68, 3823–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, T.; Baker, S.J.; Zhang, Y.K.; Hernandez, V.; Zhou, H.; Sanders, V.; Freund, Y.; Kimura, R.; Maples, K.R.; Plattner, J.J. Discovery and structure-activity study of a novel benzoxaborole anti-inflammatory agent (AN2728) for the potential topical treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2129–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vymazal, O.; Papatheodorou, I.; Andrejčinová, I.; Bosáková, V.; Vascelli, G.; Bendíčková, K.; Zelante, T.; Hortová-Kohoutková, M.; Frič, J. Calcineurin-NFAT signaling controls neutrophils’ ability of chemoattraction upon fungal infection. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2024, 116, 816–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuetz, A.; Grassberger, M.; Meingassner, J.G. Pimecrolimus (Elidel, SDZ ASM 981)--preclinical pharmacologic profile and skin selectivity. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2001, 20, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassberger, M.; Baumruker, T.; Enz, A.; Hiestand, P.; Hultsch, T.; Kalthoff, F.; Schuler, W.; Schulz, M.; Werner, F.J.; Winiski, A.; et al. A novel anti-inflammatory drug, SDZ ASM 981, for the treatment of skin diseases: In vitro pharmacology. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999, 141, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaupré, V.; Boucher, N.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Thykamine Extracts from Spinach Reduce Acute Inflammation In Vivo and Downregulate Phlogogenic Functions of Human Blood Neutrophils In Vitro. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Pierre, A.; Blondeau, D.; Boivin, M.; Beaupré, V.; Boucher, N.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Study of antioxidant properties of thylakoids and application in UV protection and repair of UV-induced damage. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 18, 1980–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, A.P. Coronavirus disease 2019: The prospect for botanical drug’s polymolecular approach. Int. J. Noncomm. Dis. 2021, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crombie, B. PurGenesis Technologies Reports Excellent Safety and Biological Activity from a 2-Week Phase IIa Proof of Concept Clinical Trial with PUR 0110 for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. 2013. Available online: https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/purgenesis-technologies-reports-excellent-safety-and-biological-activity-from-a-2-week-phase-iia-proof-of-concept-clinical-trial-with-pur-0110-for-the-treatment-of-ulcerative-colitis-512777271.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Lynde, C.; Poulin, Y.; Tan, J.; Lomaga, M.; Loo, W.J.; Carbonneau, D.; Delorme, I.; Grimard, D.; Sampalis, J. Phase 2 Trial of Topical Thykamine in Adults With Mild to Moderate Atopic Dermatitis. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2022, 21, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Jantan, I.; Harikrishnan, H.; Ghazalee, S. Standardized extract of Zingiber zerumbet suppresses LPS-induced pro-inflammatory responses through NF-κB, MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in U937 macrophages. Phytomedicine 2019, 54, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, P.L.; KalinĔski, P.; Wierenga, E.A.; Kapsenberg, M.L.; de Jong, E.C. Glucocorticoids Inhibit Bioactive IL-12p70 Production by In Vitro-Generated Human Dendritic Cells Without Affecting Their T Cell Stimulatory Potential1. J. Immunol. 1998, 161, 5245–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetti, A.; Feliciani, C.; Tulli, A.; Amerio, P. Pharmacotherapy of Inflammatory and Pruritic Manifestations of Corticosteroid-Responsive Dermatoses Focus on Clobetasol Propionate. Clin. Med. Insights 2010, 2, CMT.S1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinehart, J.J.; Balcerzak, S.P.; Sagone, A.L.; LoBuglio, A.F. Effects of Corticosteroids on Human Monocyte Function. J. Clin. Investig. 1974, 54, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiski, A.; Wang, S.; Schwendinger, B.; Stuetz, A. Inhibition of T-cell activation in vitro in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by pimecrolimus and glucocorticosteroids and combinations thereof. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 16, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, J.W.; Reed, W.P.; Eberle, B.; Kisch, A.L. Corticosteroids, serum, and phagocytosis: In vitro and in vivo studies. Infect Immun 1974, 9, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.J.; Kusler, B.; Otsuka, M.; Hughes, M.; Suzuki, N.; Suzuki, S.; Yeh, W.C.; Akira, S.; Han, J.; Jones, P.P. Calcineurin negatively regulates TLR-mediated activation pathways. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 4598–4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alidousty, C.; Rauen, T.; Hanssen, L.; Wang, Q.; Alampour-Rajabi, S.; Mertens, P.R.; Bernhagen, J.; Floege, J.; Ostendorf, T.; Raffetseder, U. Calcineurin-mediated YB-1 dephosphorylation regulates CCL5 expression during monocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 21401–21412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Agent | Mechanism of Action | IC50 | Route | Common Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clobetasol propionate | Binds glucocorticoid receptor | CYP3A5: 206 nM [48] CYP3A4: 15.6 μM [48] | Topical, very high potency [49] | Corticosteroid-responsive dermatoses (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, contact dermatitis) |

| Betamethasone valerate | MIP-1α: 38 nM [50] | Topical, high potency [49] | ||

| 21-acetate hydrocortisone | MIP-1α: 480 nM [50] | Topical, low potency [49] | ||

| Prednisone | IL-5: 50 nM [51] IL-2: 200 nM [51] | Oral | Cancer, various inflammatory diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, atopic dermatitis, asthma, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease) | |

| Crisaborole | Inhibits PDE4, causing increase in cAMP [52], which modulates NF-κB [53] | PDE4: 490 nM [54] TNF-α: 540 nM [54] IL-2: 610 nM [54] IFN-γ: 830 nM [54] | Topical | Mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis |

| Pimecrolimus | Inhibits calcineurin, preventing NFAT dephosphorylation, preventing transcription of key cytokines and chemokines [55] | T-cell proliferation: 0.55 nM [56,57] | Topical | Mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis |

| Agent Name | Concentration Levels | Manufacturer | Catalog | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Thykamine™ (µg/mL) | 125 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | Devonian Health Group (Montmagny, QC, Canada) | N/A |

| Clobetasol propionate (nM) | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | 50 | Sigma-Aldrich | C8037 |

| Betamethasone valerate (nM) | 0.1 | 1 | 10 | 50 | Sigma-Aldrich | PHR1780 |

| 21-acetate hydrocortisone (µM) | 1 | 10 | 50 | 250 | Sigma-Aldrich | H0888 |

| Crisaborole (µM) | 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) | 21455 |

| Pimecrolimus (nM) | 100 | 300 | 600 | - | Sigma-Aldrich | SML1437 |

| Prednisone (µM) | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | Sigma-Aldrich | P6254 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lynde, C.; Flamand, L.; McCarty, V.; Sampalis, J. Thykamine™: A New Player in the Field of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122938

Lynde C, Flamand L, McCarty V, Sampalis J. Thykamine™: A New Player in the Field of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122938

Chicago/Turabian StyleLynde, Charles, Louis Flamand, Vincent McCarty, and John Sampalis. 2025. "Thykamine™: A New Player in the Field of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122938

APA StyleLynde, C., Flamand, L., McCarty, V., & Sampalis, J. (2025). Thykamine™: A New Player in the Field of Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2938. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122938