1. Introduction

Sore throat, a symptom encompassing a painful, scratchy and burning sensation in the throat, is most often of infectious etiology, with viruses responsible for 90% of adult sore throats [

1,

2,

3]. Group A ß-hemolytic streptococci are the most prevalent bacterial cause (5–36%) [

2]. Sore throat can also have a non-infectious etiology, most often due to physico-chemical factors, such as smoking, snoring and shouting, or environmental factors, such as pollution, humidity or air conditioning [

2]. It can also be a minor complication of intubation, expressed as postoperative sore throat (POST) and hoarseness as a result of trauma to the upper airway, resulting in inflammation, pain and altered function [

2,

4]. Sore throat, precisely acute pharyngitis, is most often self-limiting and does not produce serious consequences in otherwise healthy individuals [

3]. It is, however, shown to be a recurring condition, causing distress and disruption of everyday life, due to discomfort, difficulty swallowing and sleeping disturbances, leading to a consequent lack of productivity and focus, additionally reported as one of the most frequent reasons to seek medical care [

1]. It can be accompanied by fever, cough, swollen lymph nodes and hoarseness [

1]. Due to its etiological heterogeneity and diverse clinical presentations, it is hard to adequately identify the cause and start targeted treatment [

1]. Moreover, there are differences in treatment guidelines between regions and institutions, often leading to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing [

1]. This is further encouraged by patients wanting quick relief and a lack of accurate diagnostic tools, leading to antibiotic overuse and antimicrobial resistance (AMR), even though the majority of cases are viral [

1]. Therefore, effective and safe symptomatic treatment is of high importance. As a sore throat is a result of inflammation of mucous membranes in the oropharynx accompanied by the release of inflammatory mediators, specifically of prostaglandins (PGE

2), topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the intuitive choice, with flurbiprofen showing rapid anti-inflammatory activity in vitro [

5,

6]. Flurbiprofen is a NSAID, demonstrating anti-inflammatory, antipyretic and analgesic properties, initially used in rheumatology [

7]. Its use in acute inflammation of the upper respiratory tract started with systemic use in a study published in 1986, but then shifted to local administration in the treatment of sore throat in studies published in the early 2000s [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Flurbiprofen administered locally penetrates through all layers of the pharynx mucosal tissue and reaches the lamina propria, which contains blood vessels and nerve fibers contributing to pain [

6]. There are many studies investigating the efficacy and safety of flurbiprofen in the symptomatic treatment of sore throat, mostly in the context of URTIs, with fewer studies investigating its effect in non-infectious cases. The aim of our scoping review is to provide an overview of the literature on flurbiprofen in the treatment of sore throat of both infectious and non-infectious etiologies, focusing on different clinical features such as pain, difficulty swallowing and throat swelling, while also assessing its effect on other URTI symptoms and overall safety, intending to highlight possible research gaps and provide objective conclusions to further guide concrete treatment recommendations.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews, and the PRISMA 2020 checklist is included in the

Supplementary Table S1. The scoping review was registered in the OSF database registry htpps://osf.io/mcb6d (accessed on 23 October 2025). The database PubMed was searched. In the initial search, the search terms flurbiprofen, sore throat and acute pharyngitis were used. The initial search revealed 49 articles (

Table 1). The results were then limited to articles published in the last 10 years to ensure the most up-to-date results. This search revealed 30 articles in total. An additional language filter was applied, limiting the search to articles published in English. This final search, performed on 28th August 2025 at 10:20 am, revealed 27 articles that were considered in the further screening process.

The identified publications had to then be screened according to the PICOS defined in

Table 2, demonstrating the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies considered for this scoping review.

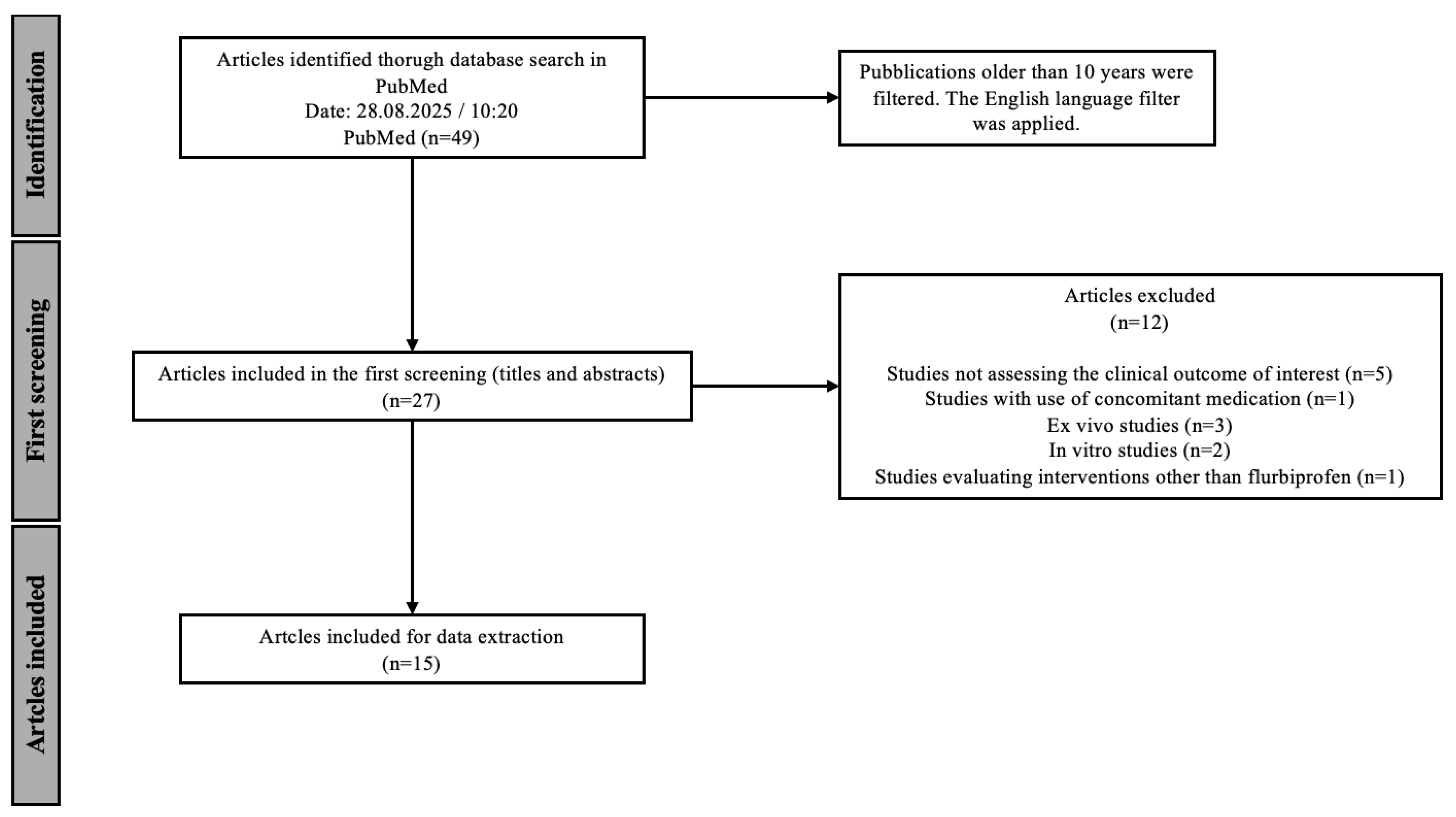

The entirety of the screening process is demonstrated graphically in

Figure 1. In the initial screening, titles and abstracts were analyzed and 12 studies were excluded based on the exclusion criteria shown in

Table 2. Due to the aim of this scoping review, five articles examining outcomes other than pain relief and overall symptomatic relief of sore throat were excluded, some of which were limited to the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of flurbiprofen and not the clinical outcome studied in this scoping review. Studies conducted in vitro or ex vivo (

N = 5) were also excluded, as well as studies using other interventions (

N = 1) or concomitant medication (

N = 1). At the end of the screening, 15 articles were chosen for data extraction. When multiple publications reported data from the same clinical trial, these were considered as a single study for the purpose of participant counting, while relevant additional analyses were extracted separately. The results of the analysis are presented in tables and figures.

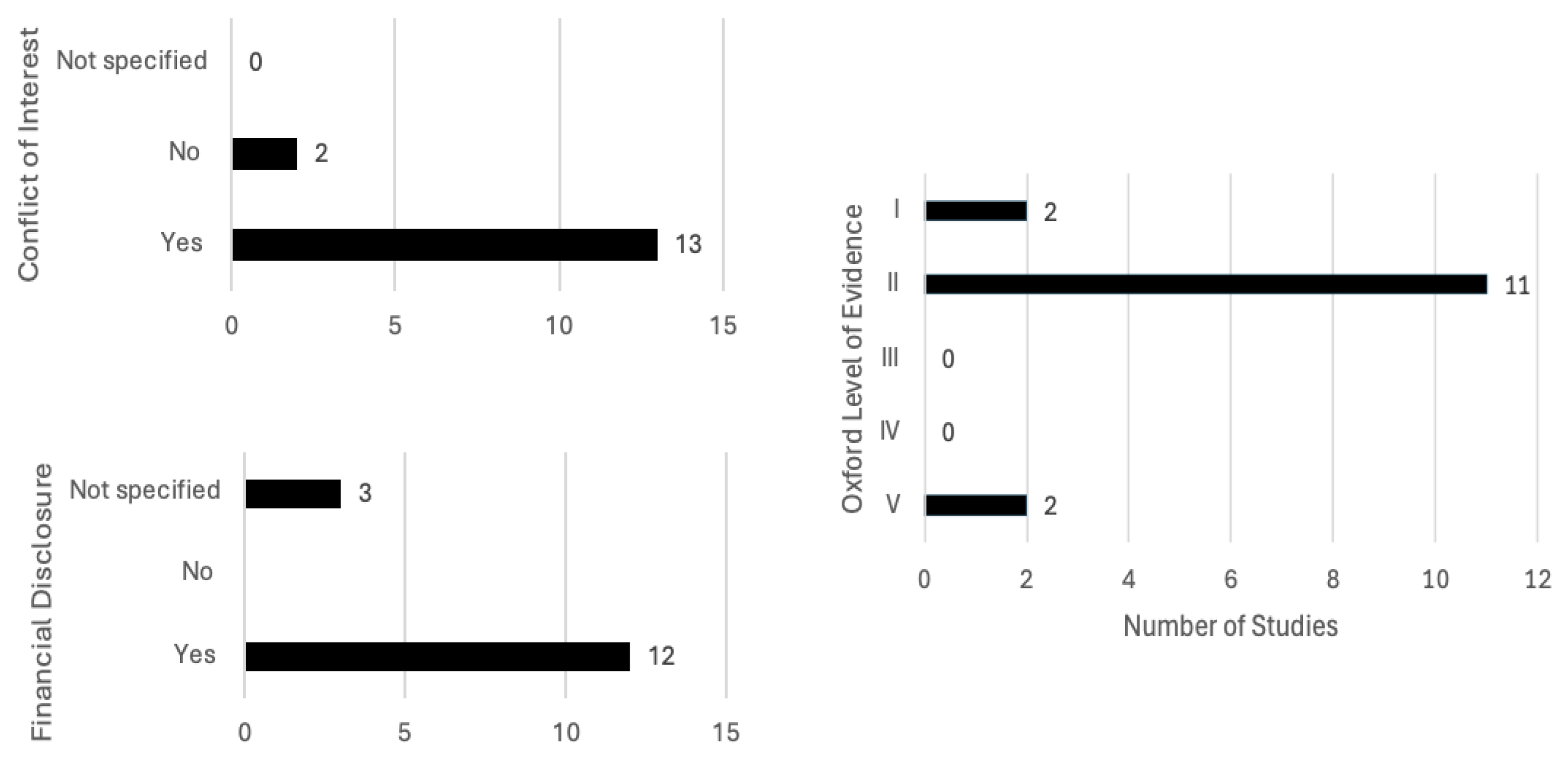

The chosen papers were evaluated using the Oxford Level of Evidence Guideline

https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on the 29 August 2025). This guideline provides a framework for ranking the quality and reliability of research papers, dividing them into five categories. Level V represents the lowest level, papers based on mechanics-based reasoning, while Level I represents the highest level of evidence, mostly reserved for systematic reviews. The effect size of the studies, as well as the overall quality, precision and consistency, influence the ranking of papers.

Additionally, conflicts of interest and funding of the studies were noted due to the possible bias of results.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, we sought to provide an overview of the current literature on the effectiveness of topical flurbiprofen in the management of sore throat, including both infectious and non-infectious etiologies, precisely acute pharyngitis and POST. Most studies to date have focused on acute pharyngitis, while significantly fewer studies have investigated its role in POST. Our analysis concluded that locally applied flurbiprofen 8.75 mg appears effective in alleviating all key clinical features of sore throat in acute pharyngitis (throat soreness, difficulty swallowing, throat swelling) and in the prevention of POST. In our review, we evaluated locally applied flurbiprofen without stratifying findings by formulations, as two included studies reported no differences between the spray and lozenge across all clinical features, thus allowing the choice to be guided by individual preference. Similar results to ours were presented in a narrative review published by de Looze et al. in 2019, where they concluded that flurbiprofen is a useful first-line treatment option for symptomatic relief in sore throat associated with URTI and as a preoperative treatment for reduction in early POST [

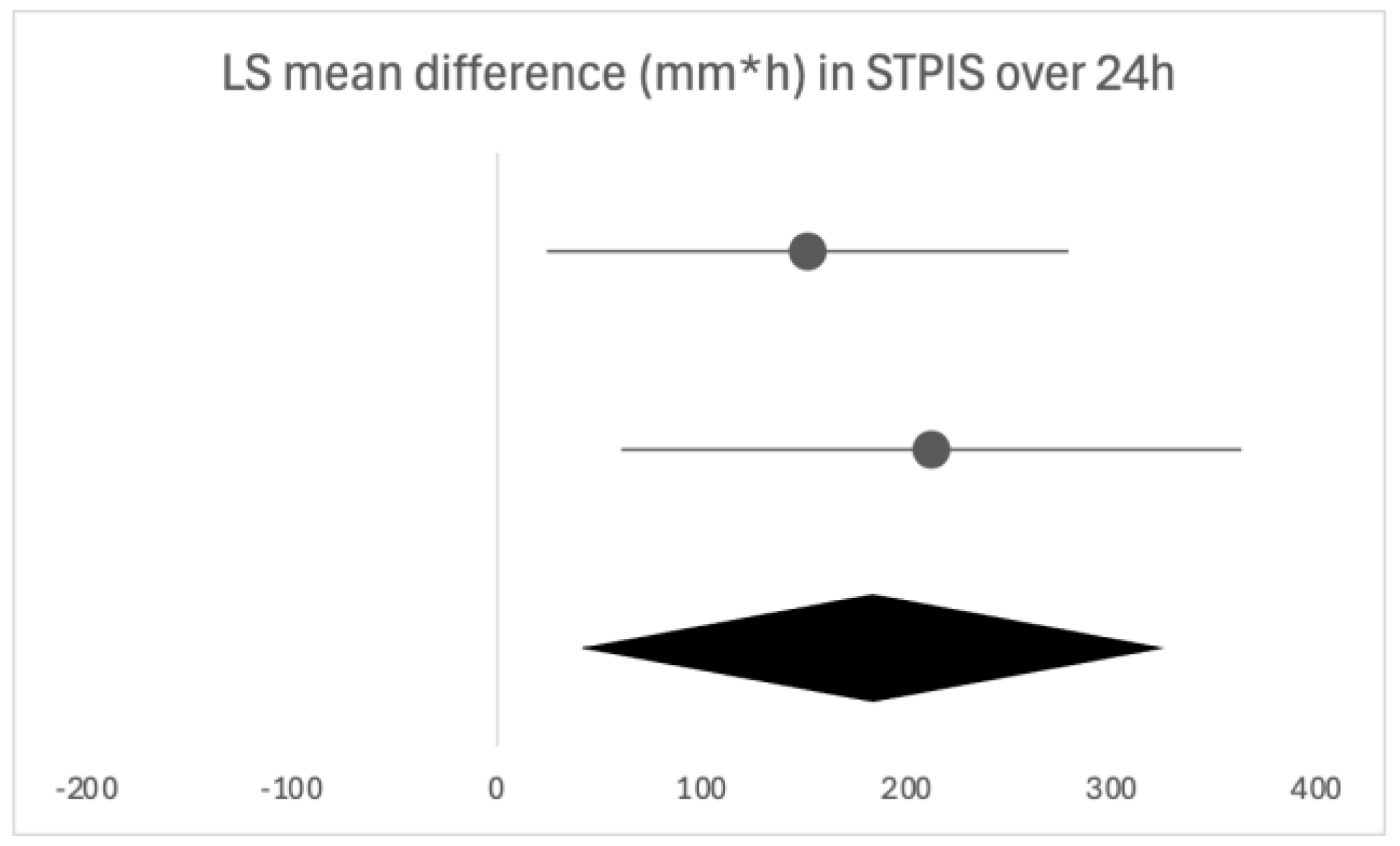

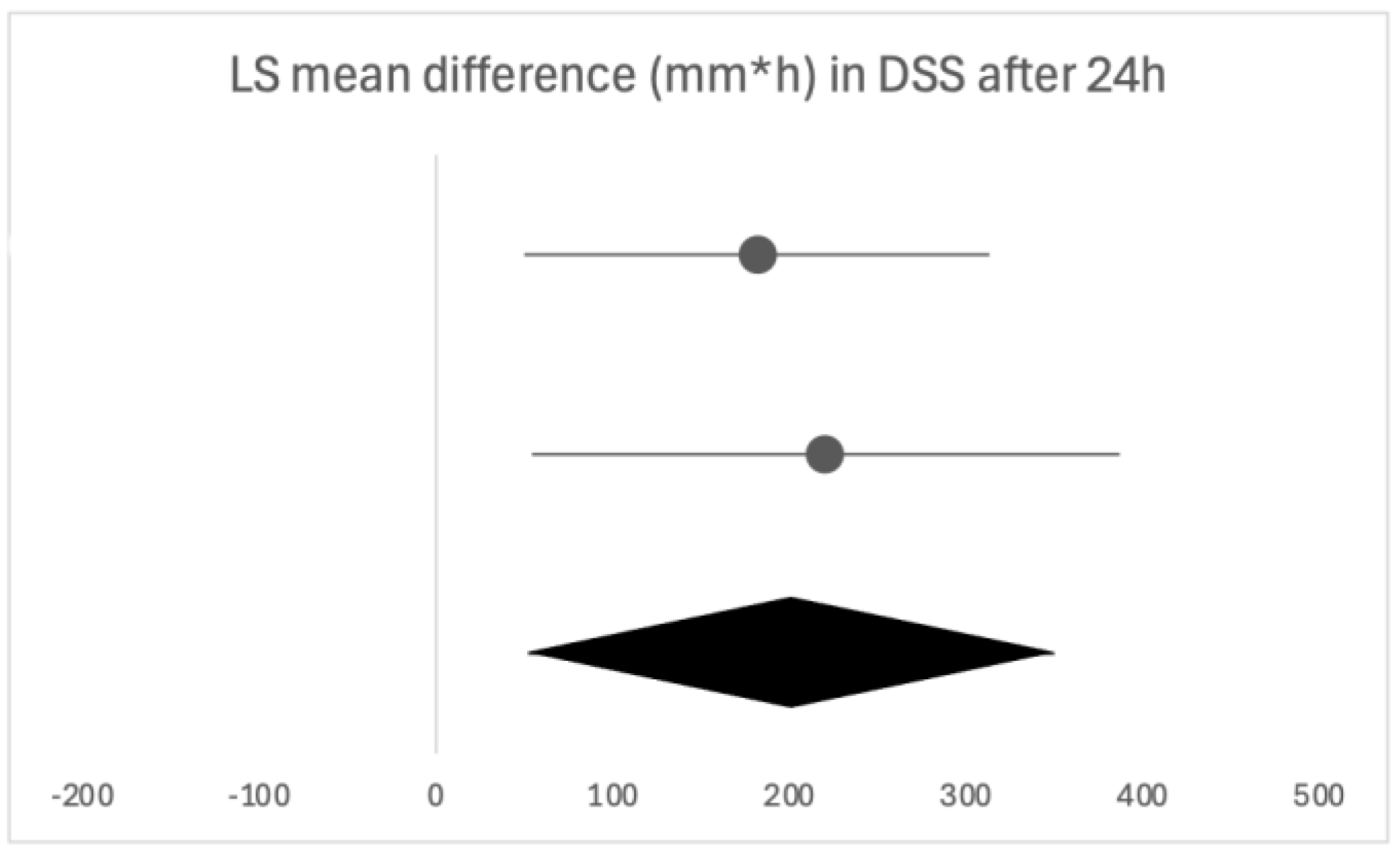

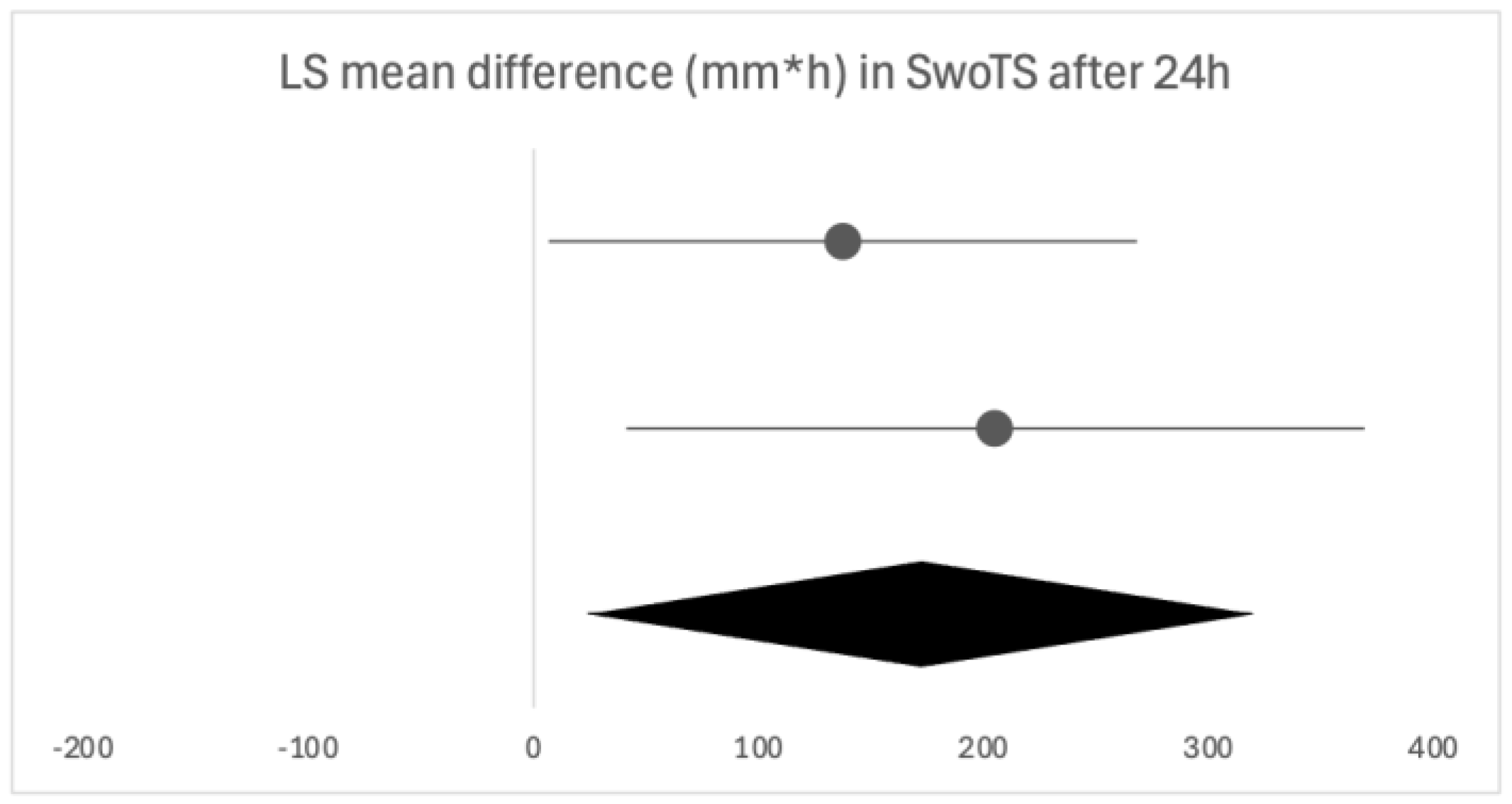

23]. In the included papers, sore throat was evaluated by different questionnaires, all focused on different aspects of the broad term; hence, we divided our analysis accordingly. Pain relief was the only symptom evaluated with multiple questionnaires, all of which ultimately yielded consistent conclusions. As the results are reported heterogeneously, we performed a qualitative analysis and presented all the available evidence and conclusions in the current literature.

Firstly, we will discuss the effect of flurbiprofen in acute pharyngitis. When overall satisfaction with the treatment was evaluated by patients and clinicians, the satisfaction rate was significantly higher with flurbiprofen than with placebo. The onset of action of flurbiprofen is quick, with significant pain relief occurring as early as five minutes and 22 min at the latest following administration, especially important due to the distressing nature of the symptom. Similar results were noted in the assessment of difficulty swallowing. Throat swelling decreased in the first assessments, which were performed later compared to the other two parameters, at 30 and 60 min, leaving room for discussion as to whether the actual onset time is earlier than assessed. The instructions are to take flurbiprofen every three to six hours, as needed, which is in line with the findings in our review, as the duration of the effect of a single dose was three to six hours, depending on the follow-up time [

25]. Acute pharyngitis typically resolves within three to seven days, with symptoms sometimes persisting for up to ten days; hence, multiple doses of flurbiprofen are required in its treatment, and this aspect was also examined in the included studies [

6,

26]. Following the usual clinical course, seven days was the longest assessment time, where flurbiprofen was shown as effective in all of the analyzed clinical features. The same conclusion can be drawn from studies opting for shorter follow-ups of 24 to 72 h, confirming the beneficial effects of flurbiprofen after multiple doses. While the majority used multiple questionnaires to assess different clinical features, an alternative is QuaSTI, a composite index including all of the mentioned clinical features, divided into three factors, which was used as an assessment tool in three of the studies. This index is said to be useful in the direct comparison of analgesic products for sore throat, possibly enabling a more direct comparison [

27]. The results in the included studies were consistent with the findings from the individual evaluations, making it a good comprehensive assessment tool. As acute pharyngitis is often part of an upper respiratory tract infection, accompanied by other relevant clinical symptoms, we examined whether the effect of flurbiprofen went beyond the relief of a sore throat and had an effect on the other accompanying symptoms in a URTI. Flurbiprofen was shown to provide an overall greater relief of these symptoms than placebo. It is important to note, however, that topical flurbiprofen provides symptomatic relief primarily through local effects, rather than systemic, as stated by a paper published in 2023 examining the relationship between the pharmacokinetic profile and clinical efficacy data of flurbiprofen [

28]. It is possible that some of the questioned symptoms, such as lack of energy, loss of appetite, coughing and mouth breathing, were a consequence of the sore throat and had therefore disappeared following sore throat relief with flurbiprofen. Another thing to note is that most of the assessments on URTI symptoms were performed after a single dose of flurbiprofen, leading us to question whether a complete resolution of these symptoms could be accomplished in such a short time frame, as the symptoms are usually present for up to ten days [

26]. There is an opportunity for future research to explore whether topical flurbiprofen has a direct effect on the duration of URTIs accompanied by sore throat. This would provide insight into its potential to not only relieve symptoms but also to influence the overall course of the infection.

As stated in the introduction, an important motive for the investigation of the effects of flurbiprofen on sore throat is the inappropriate use of antibiotics and the development of antimicrobial resistance, as the majority of adult cases of acute pharyngitis are of viral origin [

1]. That said, in cases where bacterial etiology is confirmed, antibiotics are an essential part of treatment [

20,

26]. One of the included studies investigated the effects of flurbiprofen both before and during antibiotic administration in bacterial pharyngitis and found that antibiotics alone did not provide a significant relief of symptoms in the 24 h assessment time. This points to the conclusion that while antibiotics are essential in the treatment of bacterial pharyngitis, as they treat the cause itself, additional symptomatic therapy, such as flurbiprofen, should be provided to patients to alleviate symptoms, especially in the initial stages of treatment.

When assessing the effect of flurbiprofen in non-infectious etiologies of sore throat, only POST was investigated. Flurbiprofen was shown as effective in preventing and reducing the severity of POST when administered both before and after intubation (before extubation). This was accompanied by greater satisfaction of patients than with placebo and a smaller incidence and severity of hoarseness post-intubation. Since there are no studies investigating the effect of flurbiprofen on other non-infectious causes of sore throat, further studies are needed in this area. As pain and discomfort in a sore throat are a result of a release of inflammatory mediators, even in non-infectious causes of sore throat, it is reasonable to anticipate the beneficial effect of flurbiprofen even in these instances [

6].

As with any treatment, safety should be a top priority, especially in symptomatic treatment and over-the-counter medication. Therefore, almost all of the included studies examined the safety profile of flurbiprofen. Topical flurbiprofen is shown to be a safe option for the symptomatic relief of sore throat, as no serious adverse effects were reported, and the overall number of treatment-related adverse effects was low. Local NSAIDs were shown to be a safer option than oral NSAIDs in a consensus document by Abdullah et al. [

1], with all of the other included studies pointing to the efficacy of these treatment options, making them an overall better choice in the symptomatic relief of a sore throat. Since none of the included studies involved children under the age of 12, there is a substantial gap in evidence for the pediatric population. There is some data of orally administered flurbiprofen, but the data is nevertheless scarce, as mentioned in the 2022 review [

25]. A study published in 2023 reported on the use of orally administered flurbiprofen for perioperative analgesia in children, reporting its safety and effectiveness [

29]. However, due to the different route and context of administration, its findings cannot be directly applied to our analysis.

Due to the uniform results demonstrating flurbiprofen as a safe and effective symptomatic treatment option for sore throat, its addition to clinical guidelines could be considered. More studies are still needed to investigate its effect on non-infectious causes of sore throat, as only POST is covered in the current literature.

In these studies, patients were generally observed under optimal conditions, for example, being instructed to refrain from oral intake several hours after administration or having the spray applied by medical staff. Such conditions are unlikely to be consistently maintained in at-home settings, which should be considered in the interpretation of these results, as the clinical effectiveness may therefore be less pronounced.

One of the limitations of this review is patient selection, as most of the participants were young adults, with no representation of the pediatric population, one with a high incidence of acute pharyngitis, in the included studies. This underscores the need to investigate the effectiveness and safety in children. Limited safety data in adults and the inherent challenges of conducting a pediatric clinical trial may account for the lack of studies, yet additional research in this population remains crucial.

Even though safety was evaluated in a large number of studies, only a small number were specifically focused on investigating the safety profile. Further data is needed to confirm the absence of drug–drug interactions and risk of hemorrhagic events, due to the low security of the current evidence. Due to the heterogeneity of clinical features and a lack of a gold standard diagnostic tool, a secure confirmation of etiology is less likely, making the further synthesis of results more difficult. Another limitation is the lack of studies investigating non-infectious etiologies other than POST, limiting the findings to acute pharyngitis and POST.