Xanthium strumarium L. Exhibits Potent Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects by Modulating MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways and Inhibiting Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.2. Plant Material

2.3. Extraction of X. strumarium

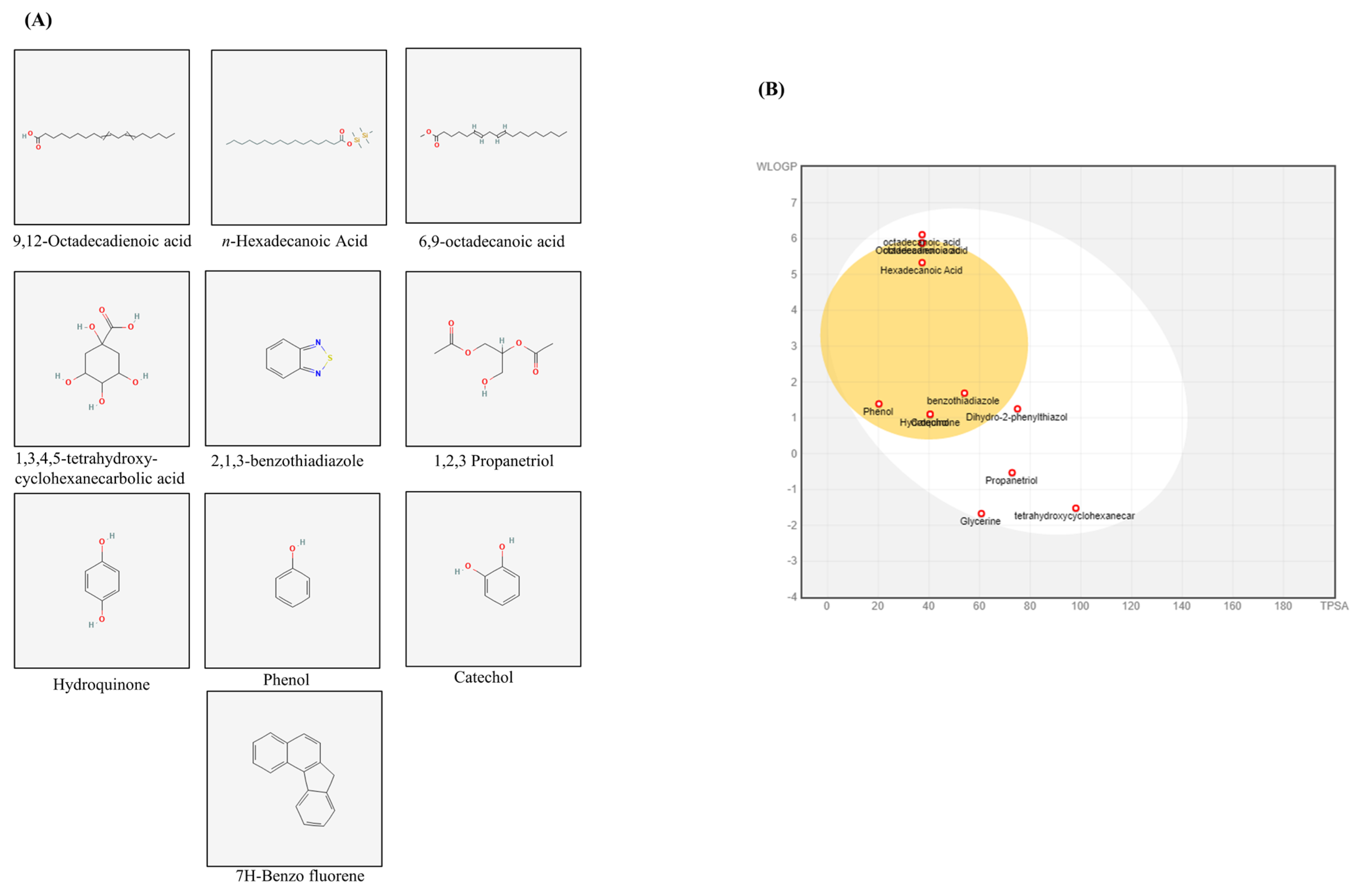

2.4. GC-MS Analysis

2.5. Experimental Animals

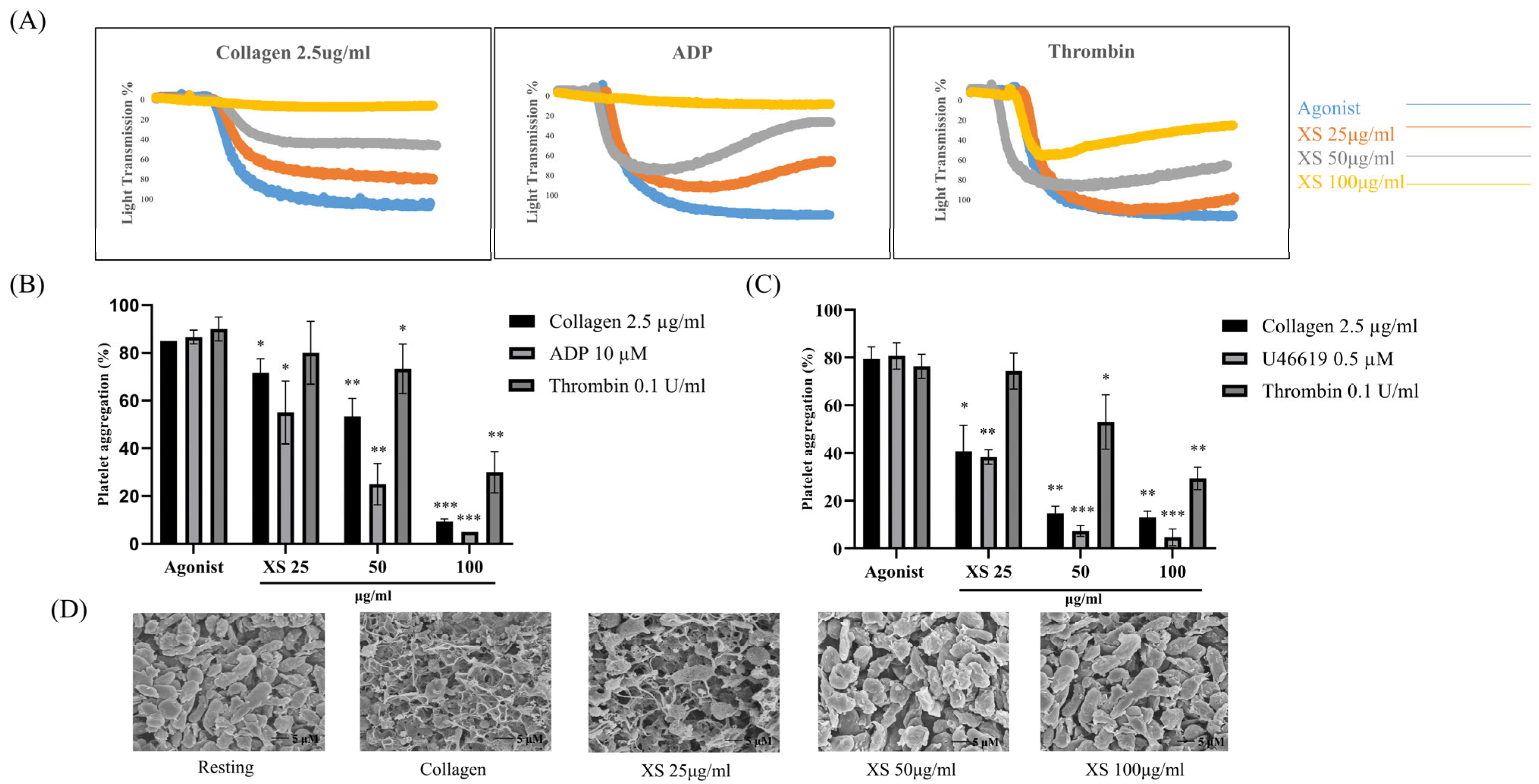

2.6. Light Transmission Aggregometry and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Cytotoxicity Measurement

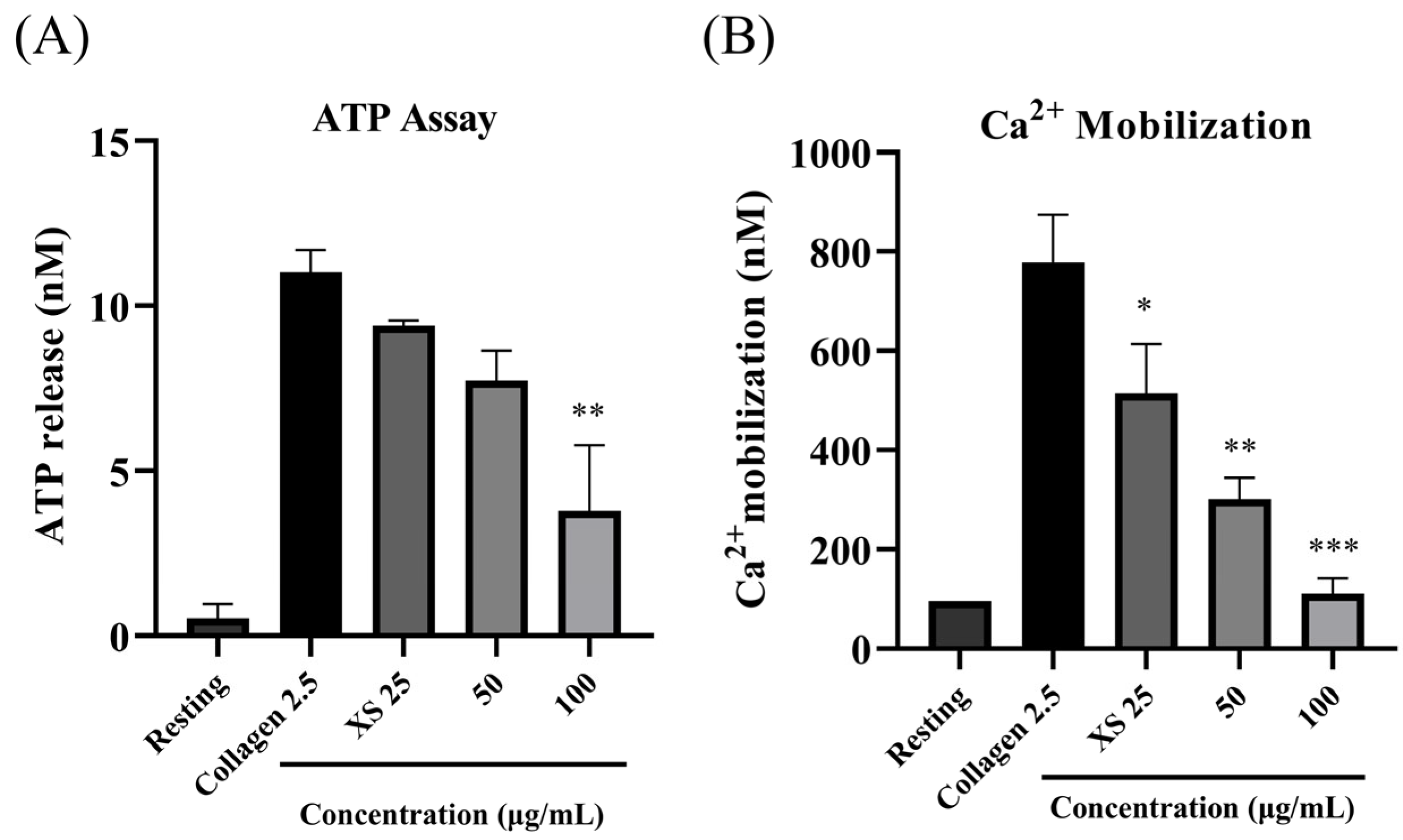

2.8. ATP Release Assay, [Ca2+]i Mobilization Assay, and Fibrinogen Binding Assay

2.9. Clot Retraction

2.10. Fibronectin Adhesion Assay and Platelet Spreading on Immobilized Fibrinogen

2.11. Western Blotting

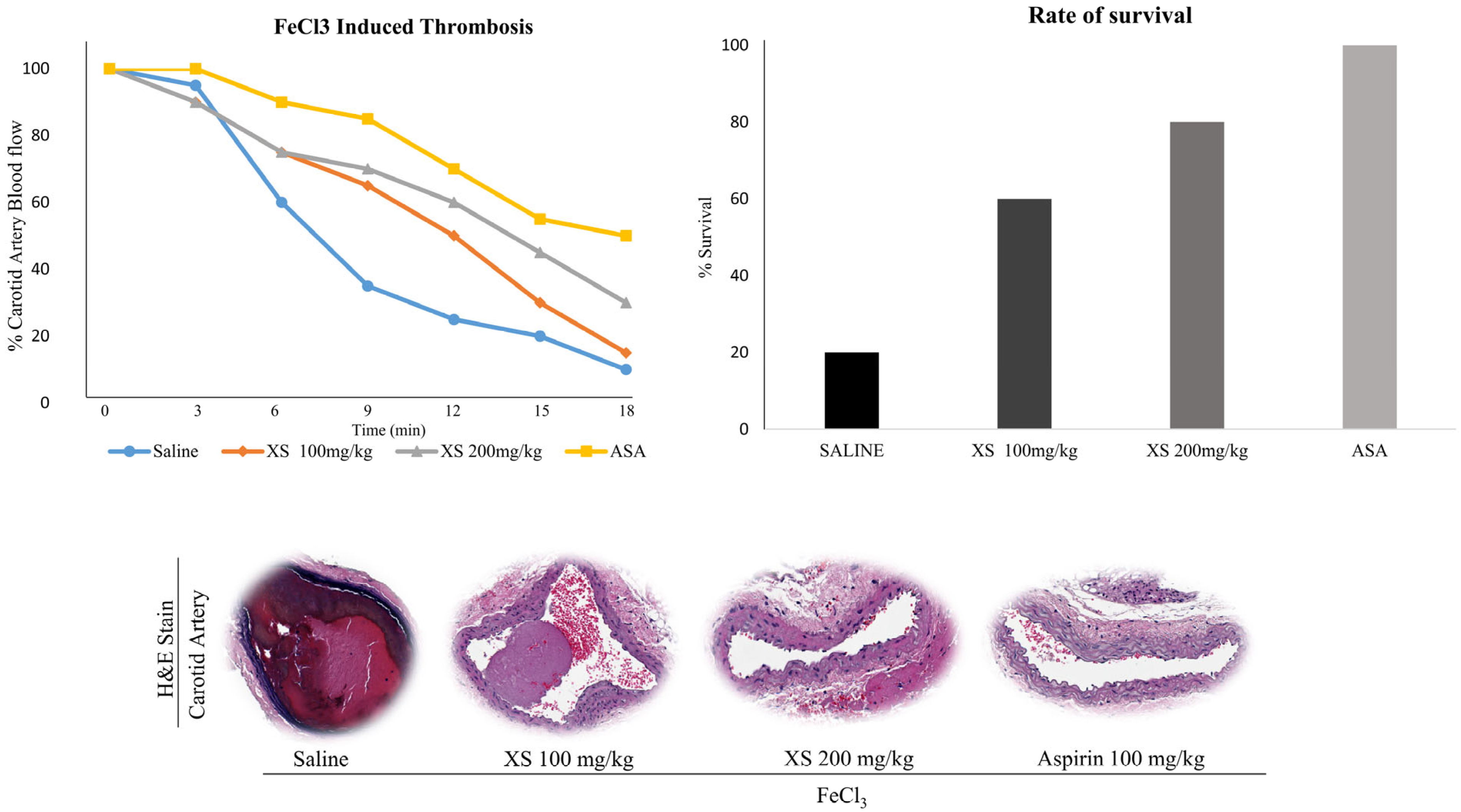

2.12. In Vivo FeCl3-Induced Thrombus Model

2.13. Drug-Likeness Analysis

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. X. strumarium Inhibits Agonist-Induced Platelet Aggregation

3.2. X. strumarium Inhibits ATP Release and [Ca2+]i Mobilization

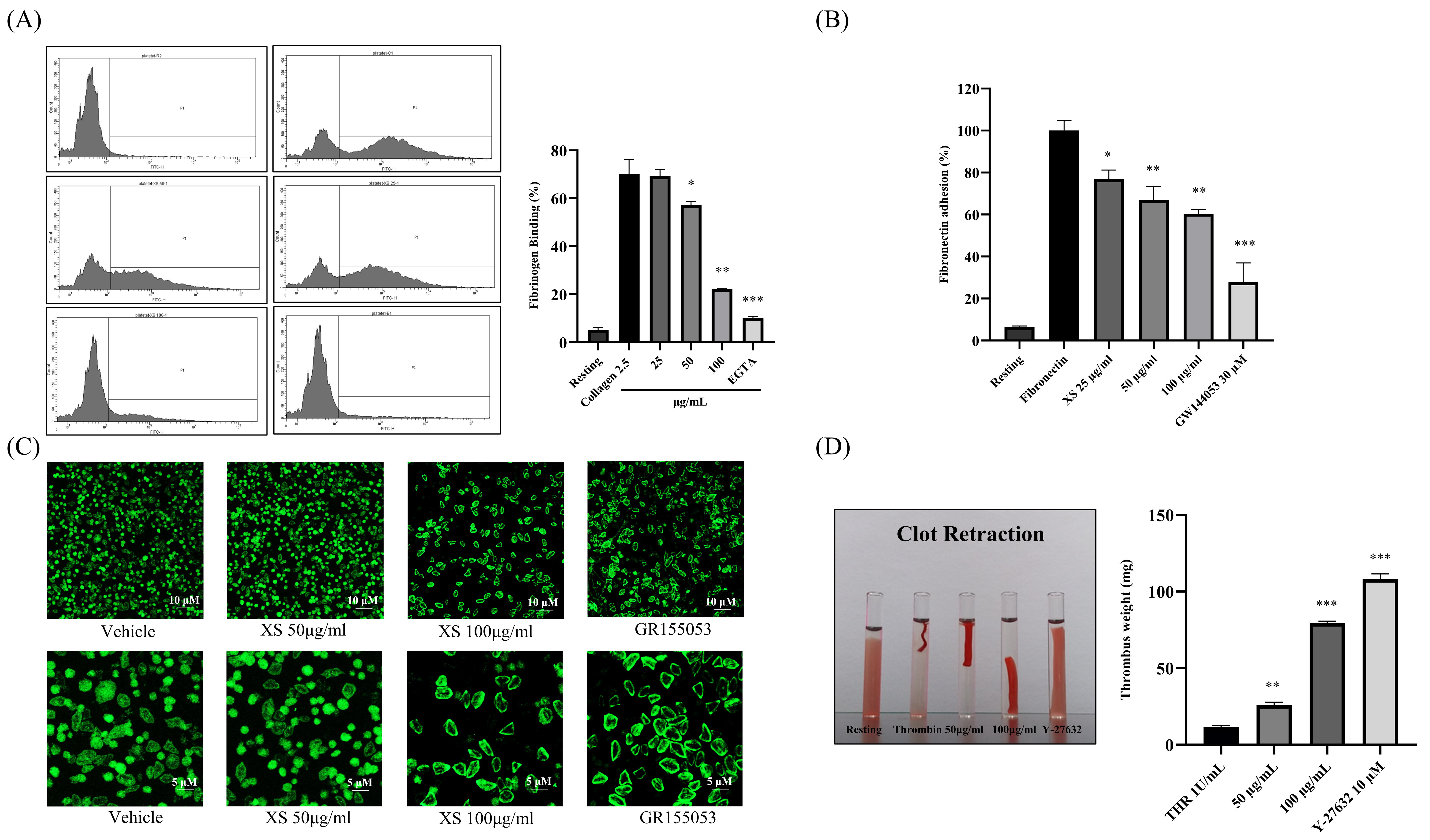

3.3. X. strumarium Downregulates Inside-Out and Outside-In Signaling

3.4. X. strumarium Attenuates MAPK and PI3K/Akt Phosphorylation

3.5. X. strumarium Prevents Thrombosis and Regulates Hemostasis

3.6. Identification of the Bioactive Compounds, Pharmacokinetics, and Drug-likeness

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form/Description |

| ACD | Acid-citrate-dextrose |

| ADP | Adenosine diphosphate |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| [Ca2+]i | Intracellular calcium concentration |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| ERK | Extracellular signal–regulated kinase |

| FeCl3 | Ferric chloride |

| ICR | Institute of Cancer Research (mouse strain) |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| OB | Oral bioavailability |

| PAR | Protease-activated receptor |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PPi | Protein–protein interaction |

| PRP | Platelet-rich plasma |

| PVDF | Poly (vinylidene fluoride) |

| RhoA | Ras homolog family member A |

| ROCK | Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| STAT1 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 |

| TXA2 | Thromboxane A2 |

| tPSA | Topological polar surface area |

| VWF | von Willebrand factor |

| WLOGP | Wildman–Crippen LogP (lipophilicity descriptor) |

| X. strumarium | Xanthium strumarium |

References

- Saina, S.; Senthil, P.; Prakash, O. Burden of illness, risk factor and physical activity in cardiovascular disease-A review. Biomedicine 2023, 43, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajlouni, Y.A.; Al Ta’ani, O.; Shamaileh, G.; Nagi, Y.; Tanashat, M.; Al-Bitar, F.; Duncan, D.T.; Makarem, N. The burden of Cardiovascular diseases in Jordan: A longitudinal analysis from the global burden of disease study, 1990–2019. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Tiwari, R.; Zhautivova, S.B.; Rakhimovna, A.H.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the role of vitamins, and herbal extracts in the reduction of cardiovascular risks. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 19, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, A.W.; Shin, J.-H.; Batmunkh, U.; Saba, E.; Kang, Y.-M.; Jung, S.; Han, J.E.; Kim, S.D.; Kwak, D.; Kwon, H.-W. Ginsenoside Rg5 inhibits platelet aggregation by regulating GPVI signaling pathways and ferric chloride-induced thrombosis. J. Ginseng Res. 2025, 49, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Kim, S.D.; Park, J.-K.; Lee, W.-J.; Han, J.E.; Seo, M.-S.; Seo, M.-G.; Bae, S.; Kwak, D.; Saba, E. Red ginseng extract inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced platelet–leukocyte aggregates in mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2024, 48, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, J.; Mackman, N.; Merrill-Skoloff, G.; Pedersen, B.; Furie, B.C.; Furie, B. Hematopoietic cell-derived microparticle tissue factor contributes to fibrin formation during thrombus propagation. Blood 2004, 104, 3190–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vögtle, T.; Cherpokova, D.; Bender, M.; Nieswandt, B. Targeting platelet receptors in thrombotic and thrombo-inflammatory disorders. Hämostaseologie 2015, 35, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swieringa, F.; Baaten, C.C.; Verdoold, R.; Mastenbroek, T.G.; Rijnveld, N.; Van Der Laan, K.O.; Breel, E.J.; Collins, P.W.; Lancé, M.D.; Henskens, Y.M.C. Platelet control of fibrin distribution and microelasticity in thrombus formation under flow. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2016, 36, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.; Palankar, R. Platelet shape changes during thrombus formation: Role of actin-based protrusions. Hämostaseologie 2021, 41, 014–021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scridon, A. Platelets and their role in hemostasis and thrombosis—From physiology to pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Bao, L.; Wu, W.; Qi, R. Fruitflow inhibits platelet function by suppressing Akt/GSK3β, Syk/PLCγ2 and p38 MAPK phosphorylation in collagen-stimulated platelets. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenazy, F.O.; Thomas, M.R. Novel antiplatelet targets in the treatment of acute coronary syndromes. Platelets 2021, 32, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Warriner, D. Manual of Cardiac Intensive Care-E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Giannenas, I.; Sidiropoulou, E.; Bonos, E.; Christaki, E.; Florou-Paneri, P. The history of herbs, medicinal and aromatic plants, and their extracts: Past, current situation and future perspectives. In Feed Additives; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, A.W.; Cho, H.-Y.; Saba, E.; Lee, G.-Y.; Park, S.-C.; Kim, S.D.; Han, Y.G.; Rhee, M.H. Innovative use of a commercial product (Biomagic) for odor reduction, harmful bacteria inhibition, and immune enhancement in pig farm. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2024, 64, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.A.; Hashmi, H.A.; Muzammal, U.; Akram, A.W.; Alvi, M.A.; Talib, M.T.; Basharat, A.; Rauf, U.; Rahman, H.M.S.; ur Rahman, H.M.H. Use of Natural Feed Additives as a Remedy for Diseases in Veterinary Medicine. In Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Feed Additives; Unique Scientific Publishers: Punjab, Pakistan, 2024; Volume 104. [Google Scholar]

- Asfaw, T.B.; Esho, T.B.; Bachheti, A.; Bachheti, R.K.; Pandey, D.P.; Husen, A. Exploring important herbs, shrubs, and trees for their traditional knowledge, chemical derivatives, and potential benefits. In Herbs, Shrubs, and Trees of Potential Medicinal Benefits; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pirintsos, S.; Panagiotopoulos, A.; Bariotakis, M.; Daskalakis, V.; Lionis, C.; Sourvinos, G.; Karakasiliotis, I.; Kampa, M.; Castanas, E. From traditional ethnopharmacology to modern natural drug discovery: A methodology discussion and specific examples. Molecules 2022, 27, 4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R. Exploring Approaches for Investigating Phytochemistry: Methods and Techniques. Medalion J. Med. Res. Nurs. Health Midwife Particip. 2023, 4, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, A.W.; Saba, E.; Rhee, M.H. Antiplatelet and antithrombotic activities of Lespedeza cuneata via pharmacological inhibition of integrin αIIbβ3, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT pathways and FeCl3-induced murine thrombosis. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2024, 2024, 9927160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamponi, S. Bioactive natural compounds with antiplatelet and anticoagulant activity and their potential role in the treatment of thrombotic disorders. Life 2021, 11, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, S.S.; Adesibikan, A.A.; Olusola Olawoyin, C.; Bayode, A.A. A Review of Antithrombolytic, Anticoagulant, and Antiplatelet Activities of Biosynthesized Metallic Nanostructured Multifunctional Materials. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202302712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micek, A.; Godos, J.; Del Rio, D.; Galvano, F.; Grosso, G. Dietary flavonoids and cardiovascular disease: A comprehensive dose–response meta-analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 2001019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant polyphenols and their potential benefits on cardiovascular health: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, S.; Zehra, A.; Mukarram, M.; Wani, K.I.; Naeem, M.; Hakeem, K.R.; Aftab, T. Potential uses of bioactive compounds of medicinal plants and their mode of action in several human diseases. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Healthcare and Industrial Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Wu, B.; Han, J.; Tan, N. Phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Xanthium species: A review. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 24, 773–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Fan, L.; Peng, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Peng, W.; Wu, C. Traditional uses, botany, phytochemistry, pharmacology, pharmacokinetics and toxicology of Xanthium strumarium L.: A review. Molecules 2019, 24, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Wahab, A.; Perveen, R.; Haider, S.S.; Farheen, R.; Anwar, A. A Brief Review on phytochemistry and Pharmacological Activity of Xanthium strumarium L. FUUAST J. Biol. 2019, 9, 271–276. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.; Shah, S.; Ullah, S. Ethnomedicinal, pharmacological and phytochemical evaluation of Xanthium strumarium L. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2020, 11, 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.R.; Uddin, M.Z.; Rahman, M.S.; Tutul, E.; Rahman, M.Z.; Hassan, M.A.; Faiz, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Hussain, M.; Rashid, M.A. Ethnobotanical, phytochemical and toxicological studies of Ghagra shak (Xanthium strumarium L.) growing in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Med. Res. Counc. Bull. 2010, 35, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, A.W.; Batmunkh, U.; Rhee, M.H. In-vitro Evaluation of Free Radical Scavenging Activities and Inflammatory Markers from LPS-Induced MH-S Cells by Xanthium strumarium L. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2024, 54, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chutia, G.P.; Chutia, S.; Kalita, P.; Phukan, K. Xanthium strumarium seed as a potential source of heterogeneous catalyst and non-edible oil for biodiesel production. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 172, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Soliman, M.M.; Al-Otaibi, S.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Taha, E.-K.A.; Sayed, S. The effectiveness of Xanthium strumamrium L. Extract and Trichoderma spp. Against pomegranate isolated pathogenic fungi in taif, Saudi Arabia. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2022, 34, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Wu, C.-H.; Malak, N.; Khan, A.; Ullah, S.; Ahmad, I.; Khan, M.A.; Naveed, M.; Ullah, Z.; Naz, S. In vitro Bioassay and In silico Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of Xanthium strumarium Plant Extract as Possible Acaricidal Agent. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2025, 31, 992–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Min, Y.S.; Park, K.-C.; Kim, D.-S. Inhibition of Melanogenesis by Xanthium strumarium L. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2012, 76, 767–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Akram, A.W.; Kim, Y.-H.; Irfan, M.; Kim, S.D.; Saba, E.; Kim, T.W.; Yun, B.-S.; Rhee, M.H. Geum japonicum Thunb. exhibits anti-platelet activity via the regulation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1538417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, A.; Sim, H.; Choi, K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kang, B.; No, Y.S.; Lee, D.; Lee, I.; Lee, J. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Lespedeza cuneata in Coal fly ash-induced murine alveolar macrophage cells. Korean J. Vet. Res. 2023, 63, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Lee, J.P.; Heo, N.Y.; Lee, C.-D.; Kim, G.; Wahab, A.A.; Rhee, M.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, D.-H. Dioscin from smilax china rhizomes inhibits platelet activation and thrombus formation via up-regulating cyclic nucleotides. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Kwon, T.-H.; Kwon, H.-W.; Rhee, M.H. Pharmacological actions of dieckol on modulation of platelet functions and thrombus formation via integrin αIIbβ3 and cAMP signaling. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 177, 106088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.-H.; Kim, H.-H.; Cho, H.-J.; Bae, J.-S.; Yu, Y.-B.; Park, H.-J. Antiplatelet effects of caffeic acid due to Ca2+ mobilizationinhibition via cAMP-dependent inositol-1, 4, 5-trisphosphate receptor phosphorylation. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2014, 21, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.; Kwon, I.; Park, Y.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.D.; Nam, H.S.; Park, S.; Heo, J.H. Characterization of ferric chloride-induced arterial thrombosis model of mice and the role of red blood cells in thrombosis acceleration. Yonsei Med. J. 2021, 62, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, U.J.H.; Nieswandt, B. In vivo thrombus formation in murine models. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quah, Y.; Lee, Y.Y.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, S.D.; Rhee, M.H.; Park, S.-C. In silico investigation of Panax ginseng lead compounds against COVID-19 associated platelet activation and thromboembolism. J. Ginseng Res. 2023, 47, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, A.W.; Choi, D.-C.; Chae, H.-K.; Kim, S.D.; Kwak, D.; Yun, B.-S.; Rhee, M.H. Dihydrogeodin from Fennellia flavipes Modulates Platelet Aggregation via Downregulation of Calcium Signaling, αIIbβ3 Integrins, MAPK, and PI3K/Akt Pathways. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, M.; Elaïb, Z.; Borgel, D.; Denis, C.V.; Adam, F.; Bryckaert, M.; Rosa, J.-P.; Bobe, R. NAADP/SERCA3-dependent Ca2+ stores pathway specifically controls early autocrine ADP secretion potentiating platelet activation. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, e166–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, J.D.; Chauhan, A.K.; Schaeffer, G.V.; Hansen, J.K.; Motto, D.G. Red blood cells mediate the onset of thrombosis in the ferric chloride murine model. Blood 2013, 121, 3733–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Y.C. A bioavailability score. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3164–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, P.; Flaumenhaft, R. Platelet α-granules: Basic biology and clinical correlates. Blood Rev. 2009, 23, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmsen, H. Significance of testing platelet functions in vitro. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 24, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Swieringa, F.; de Laat, B.; de Groot, P.G.; Roest, M.; Heemskerk, J.W.M. Reversible platelet integrin αIIbβ3 activation and thrombus instability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrdinova, J.; Fernández, D.I.; Ercig, B.; Tullemans, B.M.E.; Suylen, D.P.L.; Agten, S.M.; Jurk, K.; Hackeng, T.M.; Vanhoorelbeke, K.; Voorberg, J. Structure-based cyclic glycoprotein ibα-derived peptides interfering with von Willebrand factor-binding, affecting platelet aggregation under shear. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasirer-Friede, A.; Cozzi, M.R.; Mazzucato, M.; De Marco, L.; Ruggeri, Z.M.; Shattil, S.J. Signaling through GP Ib-IX-V activates αIIbβ3 independently of other receptors. Blood 2004, 103, 3403–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, M.; Okamoto, R.; Ito, H.; Zhe, Y.; Dohi, K. Regulation of myosin light-chain phosphorylation and its roles in cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology. Hypertens. Res. 2022, 45, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Mangin, P.; Dangelmaier, C.; Lillian, R.; Jackson, S.P.; Daniel, J.L.; Kunapuli, S.P. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase β in glycoprotein VI-mediated Akt activation in platelets. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 33763–33772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.-S.; Yang, Y.-J.; Kong, X.-J.; Ma, N.; Liu, X.-W.; Li, S.-H.; Jiao, Z.-H.; Qin, Z.; Huang, M.-Z.; Li, J.-Y. Aspirin eugenol ester inhibits agonist-induced platelet aggregation in vitro by regulating PI3K/Akt, MAPK and Sirt 1/CD40L pathways. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 852, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woulfe, D.; Jiang, H.; Morgans, A.; Monks, R.; Birnbaum, M.; Brass, L.F. Defects in secretion, aggregation, and thrombus formation in platelets from mice lacking Akt2. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; De, S.; Damron, D.S.; Chen, W.S.; Hay, N.; Byzova, T.V. Impaired platelet responses to thrombin and collagen in AKT-1–deficient mice. Blood 2004, 104, 1703–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadiah, S.; Djabir, Y.Y.; Arsyad, M.A.; Rahmi, N.U.R. The cardioprotective effect of extra virgin olive oil and virgin coconut oil on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in rats. FARMACIA 2023, 71, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeoye-Isijola, M.O.; Olajuyigbe, O.O.; Jonathan, S.G.; Coopoosamy, R.M. Bioactive compounds in ethanol extract of Lentinus squarrosulus Mont-a Nigerian medicinal macrofungus. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 15, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, T.A.; Donia, T.; Saad-Allah, K.M. Characterization, antioxidant, and cytotoxic effects of some Egyptian wild plant extracts. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varadharajan, R.; Rajalingam, D.; Palani, S. GCMS/MS analysis and cardioprotective potential of Cucumis callosus on doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity in rats. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 8, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, V.F.; Erukainure, O.L.; Olofinsan, K.A.; Msomi, N.Z.; Ijomone, O.K.; Islam, M.S. Ferulic acid mitigates diabetic cardiomyopathy via modulation of metabolic abnormalities in cardiac tissues of diabetic rats. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 37, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, T. The effect of omega 3, 6, 9 and stearic acid on trace elements in ischemia/reperfusion-induced heart tissue in a rat hind limb model. J. Sci. Rep. A 2022, 50, 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sahiner, M.; Yilmaz, A.S.; Ayyala, R.S.; Sahiner, N. Poly (Glycerol) Microparticles as Drug Delivery Vehicle for Biomedical Use. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, E.A.; Demir, S.; Kazaz, I.O.; Kucuk, H.; Alemdar, N.T.; Buyuk, A.; Mentese, A.; Aliyazicioglu, Y. Arbutin abrogates testicular ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through repression of inflammation and ER stress. Tissue Cell 2023, 82, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaram, R.; Karuppaiah, M.; Shanthi, P.; Sachdanandam, P. Acute and sub acute studies of catechol derivatives from Semecarpus anacardium. Toxicol. Rep. 2018, 5, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fuentes, C.; Suarez, M.; Aragones, G.; Mulero, M.; Ávila-Román, J.; Arola-Arnal, A.; Salvadó, M.J.; Arola, L.; Bravo, F.I.; Muguerza, B. Cardioprotective properties of phenolic compounds: A role for biological rhythms. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, 2100990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.-C.; Chang, H.-H.; Wang, T.-M.; Chan, C.-P.; Lin, B.-R.; Yeung, S.-Y.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Cheng, R.-H.; Jeng, J.-H. Antiplatelet effect of catechol is related to inhibition of cyclooxygenase, reactive oxygen species, ERK/p38 signaling and thromboxane A2 production. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.C.; Chang, B.E.; Pan, Y.H.; Lin, B.R.; Lian, Y.C.; Lee, M.S.; Yeung, S.Y.; Lin, L.D.; Jeng, J.H. Antiplatelet, antioxidative, and anti-inflammatory effects of hydroquinone. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 18123–18130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kececi, H.; Ozturk, Y.; Dortbudak, M.B.; Yakut, S.; Dagoglu, G.; Ozturk, M. Time-based effects of Xanthium strumarium extract on rats. Pak. J. Zool. 2022, 54, 2681–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akram, A.W.; Lee, G.H.; Baek, S.-M.; Kang, J.; Koo, Y.; Oh, Y.; Seo, M.-S.; Saba, E.; Lee, D.-H.; Rhee, M.H. Xanthium strumarium L. Exhibits Potent Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects by Modulating MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways and Inhibiting Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122924

Akram AW, Lee GH, Baek S-M, Kang J, Koo Y, Oh Y, Seo M-S, Saba E, Lee D-H, Rhee MH. Xanthium strumarium L. Exhibits Potent Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects by Modulating MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways and Inhibiting Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122924

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkram, Abdul Wahab, Ga Hee Lee, Su-Min Baek, Jinsu Kang, Yoonhoi Koo, Yein Oh, Min-Soo Seo, Evelyn Saba, Dong-Ha Lee, and Man Hee Rhee. 2025. "Xanthium strumarium L. Exhibits Potent Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects by Modulating MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways and Inhibiting Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122924

APA StyleAkram, A. W., Lee, G. H., Baek, S.-M., Kang, J., Koo, Y., Oh, Y., Seo, M.-S., Saba, E., Lee, D.-H., & Rhee, M. H. (2025). Xanthium strumarium L. Exhibits Potent Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects by Modulating MAPK and PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathways and Inhibiting Ferric Chloride-Induced Thrombosis. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2924. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122924