Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Insights and Experience in Dermatology, Surgery, Dentistry, Ophthalmology, Rhinology, and Other Specialties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Key Characteristics of Hypochlorous Acid Related to Its Use—Mechanistic Considerations: Immunomodulation and Antiviral Activity; pH, and the Effect of Antimicrobial Activity; Practical Use Parameters and Comparative Effectiveness; Suggested Dosing Guidance

3. Hypochlorous Acid in Wound Care, Scar Management, and Postoperative Treatment

4. Hypochlorous Acid in Infection Control and Topical Preparations for Dermatoses

5. Hypochlorous Acid in the Prevention of Melanoma and Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers

6. Hypochlorous Acid in Dentistry

7. Hypochlorous Acid for Various Infections and COVID-19

8. Hypochlorous Acid in Ophthalmology and the Treatment of Eye Infections

9. Hypochlorous Acid in Otorhinolaryngology

10. Final Comments on HOCl Use in Clinical Practice

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HOCl | hypochlorous acid |

| -OCl | hypochlorite |

| LTB4 | leukotriene B4 |

| IL- | interleukin |

| MMPs | matrix metalloproteinases |

| HSV-1 | herpes simplex virus type 1 |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| TCID50 | tissue culture infectious dose |

| VZV | varicella-zoster virus |

| NO | nasal nitric oxide |

References

- Day, A.; Alkhalil, A.; Carney, B.C.; Hoffman, H.N.; Moffatt, L.T.; Shupp, J.W. Disruption of Biofilms and Neutralization of Bacteria Using Hypochlorous Acid Solution: An In Vivo and In Vitro Evaluation. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2017, 30, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

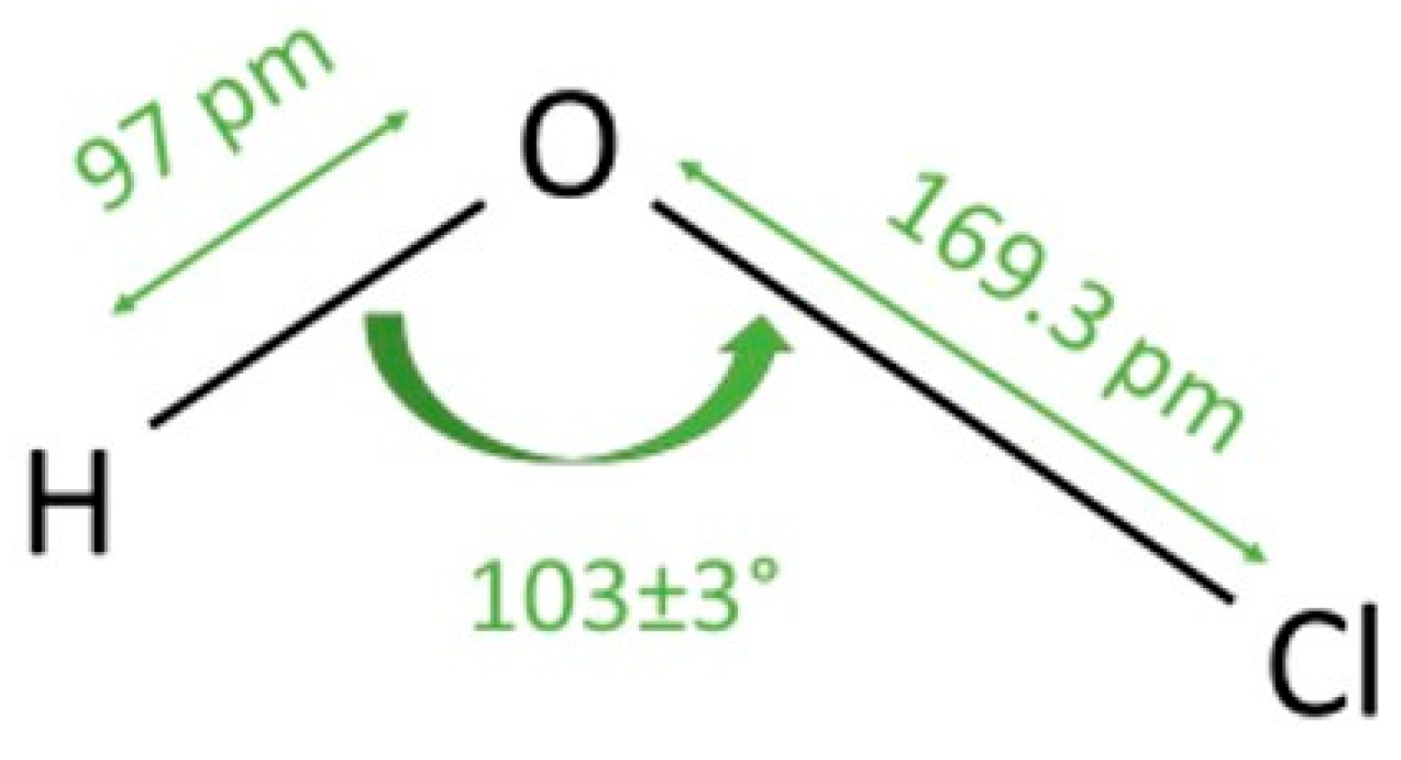

- Hypochlorous Acid. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypochlorous_acid (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Pelgrift, R.Y.; Friedman, A.J. Topical Hypochlorous Acid (HOCl) as a Potential Treatment of Pruritus. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2013, 2, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, J.A.; Jandova, J.; Wondrak, G.T. Hypochlorous Acid: From Innate Immune Factor and Environmental Toxicant to Chemopreventive Agent Targeting Solar UV-Induced Skin Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 887220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.H.; Andriessen, A.; Dayan, S.H.; Fabi, S.G.; Lorenc, Z.P.; Henderson Berg, M. Hypochlorous Acid Gel Technology—Its Impact on Postprocedure Treatment and Scar Prevention. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2017, 16, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menta, N.; Vidal, S.I.; Friedman, A. Hypochlorous Acid: A Blast from the Past. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD 2024, 23, 909–910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Totoraitis, K.; Cohen, J.L.; Friedman, A. Topical Approaches to Improve Surgical Outcomes and Wound Healing: A Review of Efficacy and Safety. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD 2017, 16, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Taha, M.; Ismail, N.H.; Jamil, W.; Yousuf, S.; Jaafar, F.M.; Ali, M.I.; Kashif, S.M.; Hussain, E. Synthesis, Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity and Crystal Structure of 2,4-Dimethylbenzoylhydrazones. Molecules 2013, 18, 10912–10929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, D.M.; Lesmana, R.; Sahiratmadja, E. Hypochlorous Acid for Wound Healing in Diabetic Rats: Effect on MMP-9 and Histology. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1853–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumville, J.C.; Lipsky, B.A.; Hoey, C.; Cruciani, M.; Fiscon, M.; Xia, J. Topical Antimicrobial Agents for Treating Foot Ulcers in People with Diabetes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD011038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, M.; Eda, R.; Maehana, S.; Fuketa, H.; Shinkai, N.; Kawamura, N.; Kitasato, H.; Hanaki, H. Virucidal Efficacy of Hypochlorous Acid Water for Aqueous Phase and Atomization against SARS-CoV-2. J. Water Health 2024, 22, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, C.-F.; Huang, H.-L. Effects of Hypochlorous Acid Mouthwash on Salivary Bacteria Including Staphylococcus aureus in Patients with Periodontal Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazawa, K.; Jadhav, R.; Azuma, M.M.; Fenno, J.C.; McDonald, N.J.; Sasaki, H. Hypochlorous Acid Inactivates Oral Pathogens and a SARS-CoV-2-Surrogate. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado-Sánchez, A.; Ponce-Olivera, R.M. Efficacy and Tolerance of Superoxidized Solution in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Inflammatory Acne. A Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Randomized, Clinical Trial. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2009, 20, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-F.; Chung, J.-J.; Ding, S.-J.; Chen, C.-C. In Vitro Cytotoxicity and Antibacterial Activity of Hypochlorous Acid Antimicrobial Agent. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 19, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishihara, M.; Murakami, K.; Fukuda, K.; Nakamura, S.; Kuwabara, M.; Hattori, H.; Fujita, M.; Kiyosawa, T.; Yokoe, H. Stability of Weakly Acidic Hypochlorous Acid Solution with Microbicidal Activity. Biocontrol Sci. 2017, 22, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severing, A.L.; Rembe, J.D.; Koester, V.; Stuermer, E.K. Safety and efficacy profiles of different commercial sodium hypochlorite/hypochlorous acid solutions (NaClO/HClO): Antimicrobial efficacy, cytotoxic impact and physicochemical parameters in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, C.L. Hypochlorous acid-mediated modification of proteins and its consequences. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peskin, A.V.; Winterbourn, C.C. Kinetics of the reactions of hypochlorous acid and amino acid chloramines with thiols, methionine, and ascorbate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Kim, H.U.; Lee, H.N.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, C.; Cha, Y.N.; Joe, Y.; Chung, H.T.; Jang, J.; Kim, K.; et al. Taurine Chloramine Stimulates Efferocytosis Through Upregulation of Nrf2-Mediated Heme Oxygenase-1 Expression in Murine Macrophages: Possible Involvement of Carbon Monoxide. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2015, 23, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianty, R.; Hirano, J.; Anzai, I.; Kanai, Y.; Hayashi, T.; Morimoto, M.; Kataoka-Nakamura, C.; Kobayashi, S.; Uemura, K.; Ono, C.; et al. Electrolyzed hypochlorous acid water exhibits potent disinfectant activity against various viruses through irreversible protein aggregation. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1284274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatanaka, N.; Yasugi, M.; Sato, T.; Mukamoto, M.; Yamasaki, S. Hypochlorous acid solution is a potent antiviral agent against SARS-CoV-2. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1496–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalingam, S.; Cai, B.; Wong, J.; Twomey, M.; Chen, R.; Fu, R.M.; Boote, T.; McCaughan, H.; Griffiths, S.J.; Haas, J.G. Antiviral innate immune response in non-myeloid cells is augmented by chloride ions via an increase in intracellular hypochlorous acid levels. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lackner, M.; Rössler, A.; Volland, A.; Stadtmüller, M.N.; Müllauer, B.; Banki, Z.; Ströhle, J.; Luttick, A.; Fenner, J.; Sarg, B.; et al. N-chlorotaurine is highly active against respiratory viruses including SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) in vitro. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Daliri, E.B.-M.; Oh, D.-H. New Clinical Applications of Electrolyzed Water: A Review. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bridges, D.F.; Lacombe, A.; Wu, V.C.H. Fundamental Differences in Inactivation Mechanisms of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Between Chlorine Dioxide and Sodium Hypochlorite. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 923964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boecker, D.; Zhang, Z.; Breves, R.; Herth, F.; Kramer, A.; Bulitta, C. Antimicrobial efficacy, mode of action and in vivo use of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) for prevention or therapeutic support of infections. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2023, 18, Doc07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, M.S.; Rowan, B.G. Hypochlorous Acid: A Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 1461–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sil, T.B.; Malyshev, D.; Aspholm, M.; Andersson, M. Boosting hypochlorite’s disinfection power through pH modulation. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Application for Inclusion in the 2021 WHO Essential Medicines List: Hypochlorous Acid (HOCl) for Disinfection, Antisepsis, and Wound Care. Rev. 2. 16 Dec 2020. WHO: Geneva, Switzerland; 2021. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/essential-medicines/2021-eml-expert-committee/applications-for-addition-of-new-medicines/a.18_hypochlorous-acid.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Proposal for the Addition and Inclusion of Hypochlorous Acid to the 2025 WHO Essential Medicines List in the Categories of Disinfection, Antisepsis, and Wound Care. Hypochlorous Acid (HOCl) for Antisepsis, Disinfection, and Wound Care in Core Categories 15.1, 15.2, and 13 Submitted 29 October 2024 Applicant and Point of Contact: Professor Suad Sulaiman, PhD Health and Environment Advisor Sudanese National Academy of Sciences Khartoum, Sudan. Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/2025-eml-expert-committee/addition-of-new-medicines/a.16_hypochlorous-acid.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Sellappan, H.; Alagoo, D.; Loo, C.; Vijian, K.; Sibin, R.; Chuah, J.A. Effect of peritoneal and wound lavage with super-oxidized solution on surgical-site infection after open appendicectomy in perforated appendicitis (PLaSSo): Randomized clinical trial. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contarlı, A.; Zihni, I.; Şirin, M.C. Effect of intraperitoneal hypochlorous acid (HOCl) on bacterial translocation in an experimental peritonitis model in rats. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2025, 31, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wan, X.; Shen, Y.; Le, Q.; Yang, P.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, F.; Gu, H.; et al. Effect of Hypochlorous Acid on Blepharitis through Ultrasonic Atomization: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jull, A.; Wadham, A.; Bullen, C.; Parag, V.; Parsons, J.G.M.; Laking, G.; Waters, J.; Klonizakis, M.; O’Brien, J. Prescribed exercise regimen versus usual care and hypochlorous acid wound solution versus placebo for treating venous leg ulcers: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (Factorial4VLU). BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Nuth, M.; Weiss, S.R.; Fausto, A.; Liu, Y.; Koo, H.; Wolff, M.S.; Ricciardi, R.P. HOCl Rapidly Kills Corona, Flu, and Herpes to Prevent Aerosol Spread. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Li, M. Evaluation of 0.01% Hypochlorous Acid Eye Drops Combined with Conventional Treatment in the Management of Fungal Corneal Ulcers: Randomized Controlled Trial. Curr. Eye Res. 2023, 48, 887–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdová, V.; Štěpánová, V.; Lapčíková, L. The Safety and Efficacy of Neutral Electrolyzed Water Solution for Wound Irrigation: Post-Market Clinical Follow-up Study. Front. Drug Saf. Regul. 2025, 4, 1402684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeqi, S.; Hashemi Shahraki, A.; Nikkhahi, F.; Javadi, A.; Marashi, S.M.A. Application of Bacteriophage Cocktails for Reducing the Bacterial Load of Nosocomial Pathogens in Hospital Wastewater. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2022, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Jalem, S.; Usharani, P. Effect of Hypochlorous Acid in Open Wound Healing. Bioinformation 2024, 20, 1619–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burian, E.A.; Sabah, L.; Kirketerp-Møller, K.; Gundersen, G.; Ågren, M.S. Effect of Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid on Re-Epithelialization and Bacterial Bioburden in Acute Wounds: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Volunteers. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2022, 102, adv00727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, E.; Pittarello, M. Wound Bed Preparation with Hypochlorous Acid Oxidising Solution and Standard of Care: A Prospective Case Series. J. Wound Care 2021, 30, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, J.M.; Robson, M.C. The Immediate and Delayed Post-Debridement Effects on Tissue Bacterial Wound Counts of Hypochlorous Acid Versus Saline Irrigation in Chronic Wounds. Eplasty 2016, 16, e32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fazli, M.M.; Kirketerp-Møller, K.; Sonne, D.P.; Balchen, T.; Gundersen, G.; Jørgensen, E.; Bjarnsholt, T. A First-in-Human Randomized Clinical Study Investigating the Safety and Tolerability of Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid in Patients with Chronic Leg Ulcers. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpan, A.L.; Cin, G.T. Comparison of Hyaluronic Acid, Hypochlorous Acid, and Flurbiprofen on Postoperative Morbidity in Palatal Donor Area: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2735–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa-Solis, C.; González-Espinosa, D.; Guzmán-Soriano, B.; Snyder, M.; Reyes-Terán, G.; Torres, K.; Gutierrez, A.A. Microcyntm: A Novel Super-Oxidized Water with Neutral pH and Disinfectant Activity. J. Hosp. Infect. 2005, 61, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Len, S.-V.; Hung, Y.-C.; Chung, D.; Anderson, J.L.; Erickson, M.C.; Morita, K. Effects of Storage Conditions and pH on Chlorine Loss in Electrolyzed Oxidizing (EO) Water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parcells, J.P.; Mileski, J.P.; Gnagy, F.T.; Haragan, A.F.; Mileski, W.J. Using Antimicrobial Solution for Irrigation in Appendicitis to Lower Surgical Site Infection Rates. Am. J. Surg. 2009, 198, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shaqsi, S.; Al-Bulushi, T. Cutaneous Scar Prevention and Management: Overview of Current Therapies. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2016, 16, e3–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, G.; Lee, J.; Ryu, J.; Oh, E.; Kim, H.; Kwak, S.; Hur, K.; Chung, H. MicroRNA-365a/b-3p as a Potential Biomarker for Hypertrophic Scars. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W. Management of Keloid Scars: Noninvasive and Invasive Treatments. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2021, 48, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekeres, G.M.; Voiţă-Mekereş, F.; Tudoran, C.; Buhaş, C.L.; Tudoran, M.; Racoviţă, M.; Voiţă, N.C.; Pop, N.O.; Marian, M. Predictors for Estimating Scars’ Internalization in Victims with Post-Traumatic Scars versus Patients with Postsurgical Scars. Healthcare 2022, 10, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeh, N.; Bharatha, A.; Gaur, U.; Forde, A.L. Keloids: Current and Emerging Therapies. Scars Burn. Heal. 2020, 6, 2059513120940499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustoe, T.A. International Scar Classification in 2019. In Textbook on Scar Management; Téot, L., Mustoe, T.A., Middelkoop, E., Gauglitz, G.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herruzo, R.; Fondo Alvarez, E.; Herruzo, I.; Garrido-Estepa, M.; Santiso Casanova, E.; Cerame Perez, S. Hypochlorous Acid in a Double Formulation (Liquid plus Gel) Is a Key Prognostic Factor for Healing and Absence of Infection in Chronic Ulcers. A Nonrandomized Concurrent Treatment Study. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.H.; Andriessen, A.; Bhatia, A.C.; Bitter, P.; Chilukuri, S.; Cohen, J.L.; Robb, C.W. Topical Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid: The Future Gold Standard for Wound Care and Scar Management in Dermatologic and Plastic Surgery Procedures. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2020, 19, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabello, F.B.; Souza, C.D.; Júnior, J.A.F. Update on Hypertrophic Scar Treatment. Clinics 2014, 69, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, F.B.; Asfaw, T.B.; Tadesse, M.G.; Gonfa, Y.H.; Bachheti, R.K. In Silico Studies as Support for Natural Products Research. Medinformatics 2024, 2, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidelix, A.; Akingbade, T.; Jangra, J.; Olabuntu, B.; Adeyemo, O.; Akingbade, J. In Silico Study and Validation of Natural Compounds Derived from Macleaya cordata as a Potent Inhibitor for BTK. Medinformatics 2025, 2, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stough, D. Topical Stabilized Super-Oxidized Hypochlorous Acid for Wound Healing in Hair Restoration Surgery: A Real-Time Usage-Controlled Trial Evaluating Safety, Efficacy, and Tolerability. J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD 2023, 22, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burian, E.A.; Sabah, L.; Kirketerp-Møller, K.; Ibstedt, E.; Fazli, M.M.; Gundersen, G. The Safety and Antimicrobial Properties of Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid in Acetic Acid Buffer for the Treatment of Acute Wounds-a Human Pilot Study and In Vitro Data. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2023, 22, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkon, J.B.; Cherry, G.W.; Wilson, J.M.; Hughes, M.A. Evaluation of Hypochlorous Acid Washes in the Treatment of Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers. J. Wound Care 2006, 15, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niezgoda, J.A.; Sordi, P.J.; Hermans, M.H.E. Evaluation of Vashe Wound Therapy in the Clinical Management of Patients with Chronic Wounds. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2010, 23, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliasson, B.; Fagerdahl, A.-M.; Jönsson, A.; Apelqvist, J. Debriding Effect of Amino Acid-Buffered Hypochlorite on Hard-to-Heal Wounds Covered by Devitalised Tissue: Pilot Study. J. Wound Care 2021, 30, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serena, T.E.; Serena, L.; Al-Jalodi, O.; Patel, K.; Breisinger, K. The Efficacy of Sodium Hypochlorite Antiseptic: A Double-Blind, Randomised Controlled Pilot Study. J. Wound Care 2022, 31 (Suppl. S2), S32–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, J. A Comparison of an Antimicrobial Wound Cleanser to Normal Saline in Reduction of Bioburden and Its Effect on Wound Healing. Ostomy. Wound Manag. 2004, 50, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Assadian, O.; Kammerlander, G.; Geyrhofer, C.; Luch, G.; Doppler, S.; Tuchmann, F.; Eberlein, T.; Leaper, D. Use of Wet-to-Moist Cleansing with Different Irrigation Solutions to Reduce Bacterial Bioburden in Chronic Wounds. J. Wound Care 2018, 27 (Suppl. S10), S10–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, E.; Pittarello, M. Hard-to-Heal Ulcers Treated with Hypochlorous Acid Oxidising Solution and Standard of Care: A 32-Week Follow-Up. J. Wound Care 2021, 30, 840–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd, A.R.R.; Ghani, M.K.; Awang, R.R.; Su Min, J.O.; Dimon, M.Z. Dermacyn Irrigation in Reducing Infection of a Median Sternotomy Wound. Heart Surg. Forum 2010, 13, E228–E232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Paola, L.; Brocco, E.; Senesi, A.; Merico, M.; Vido, D.; Assaloni, R.; DaRos, R. Feature: Super-Oxidized Solution (SOS) Therapy for Infected Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Wounds 2006, 18, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-De Jesús, F.R.; Ramos-De la Medina, A.; Remes-Troche, J.M.; Armstrong, D.G.; Wu, S.C.; Lázaro Martínez, J.L.; Beneit-Montesinos, J.V. Efficacy and Safety of Neutral pH Superoxidised Solution in Severe Diabetic Foot Infections. Int. Wound J. 2007, 4, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaggesi, A.; Goretti, C.; Mazzurco, S.; Tascini, C.; Leonildi, A.; Rizzo, L.; Tedeschi, A.; Gemignani, G.; Menichetti, F.; Del Prato, S. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Examine the Efficacy and Safety of a New Super-Oxidized Solution for the Management of Wide Postsurgical Lesions of the Diabetic Foot. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2010, 9, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, F.-Q.; Hu, Q.; Yang, F.; Hu, N.; Luo, X.N.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, N.; Li, N. Study on the Effect of Chlorogenic Acid on the Antimicrobial Effect, Physical Properties and Model Accuracy of Alginate Impression Materials. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia Shi Zhe, G.; Green, A.; Fong, Y.T.; Lee, H.Y.; Ho, S.F. Rare Case of Type I Hypersensitivity Reaction to Sodium Hypochlorite Solution in a Healthcare Setting. BMJ Case Rep. 2016, 2016, bcr2016217228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shadmehr, E.; Davoudi, A.; Sarmast, N.D.; Saatchi, M. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Efficacy of Calcium Hypochlorite as an Endodontic Irrigant on a Mixed-Culture Biofilm: An Ex Vivo Study. Iran. Endod. J. 2019, 14, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilvinaite, G.; Zongolaviciute, R.; Drukteinis, S.; Bukelskiene, V.; Cotti, E. Cytotoxicity and Efficacy in Debris and Smear Layer Removal of HOCl-Based Irrigating Solution: An In Vitro Study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, X.; Hassan, R.; Mohamad, S.; Shahidan, W.N.S. Efficacy of Oxy-Ionic Solutions With Varying pH Levels Against Streptococcus Mutans In Vitro. Cureus 2024, 16, e61025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolvos, T. The Use of Negative Pressure Wound Therapy with an Automated, Volumetric Fluid Administration: An Advancement in Wound Care. Wounds Compend. Clin. Res. Pract. 2013, 25, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X.; Nie, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Yi, Y. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Accelerate Diabetic Wound Healing by Suppressing the Expression of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2022, 23, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D. Extracellular Vesicles from Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Promote Diabetic Wound Healing via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR-HIF-1α Signaling Pathway. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Dhar, S.; De, A.; Godse, K.; Shankar, D.S.K.; Zawar, V.; Girdhar, M.; Shah, B. Use of Bleach Baths for Atopic Dermatitis: An Indian Perspective. Indian J. Dermatol. 2022, 67, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuyama, T.; Martel, B.C.; Linder, K.E.; Ehling, S.; Ganchingco, J.R.; Bäumer, W. Hypochlorous Acid Is Antipruritic and Anti-inflammatory in a Mouse Model of Atopic Dermatitis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2018, 48, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorostkar, A.; Ghahartars, M.; Namazi, M.R.; Todarbary, N.; Hadibarhaghtalab, M.; Rezaee, M. Sodium Hypochlorite 0.005% Versus Placebo in the Treatment of Mild to Moderate Acne: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, 2021046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, S.; Bhattacharya, T.; Asztalos, M.; Bohaty, B.; Durham, K.C.; West, D.P.; Hebert, A.A.; Paller, A.S. Sodium Hypochlorite Body Wash in the Management of Staphylococcus aureus—Colonized Moderate-to-severe Atopic Dermatitis in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 442–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hon, K.L.; Tsang, Y.C.K.; Lee, V.W.Y.; Pong, N.H.; Ha, G.; Lee, S.T.; Chow, C.M.; Leung, T.F. Efficacy of Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) Baths to Reduce Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Childhood Onset Moderate-to-Severe Eczema: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Cross-over Trial. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2016, 27, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaa, L.; Pernica, J.M.; Couban, R.J.; Tackett, K.J.; Burkhart, C.N.; Leins, L.; Smart, J.; Garcia-Romero, M.T.; Elizalde-Jiménez, I.G.; Herd, M.; et al. Bleach Baths for Atopic Dermatitis. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022, 128, 660–668.E9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; Shaw, R.E.; Cockerell, C.J.; Hand, S.; Ghali, F.E. Novel Sodium Hypochlorite Cleanser Shows Clinical Response and Excellent Acceptability in the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 30, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Ng, T.G.; Baba, R. Efficacy and Safety of Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) Baths in Patients with Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis in Malaysia. J. Dermatol. 2013, 40, 874–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asch, S.; Vork, D.L.; Joseph, J.; Major-Elechi, B.; Tollefson, M.M. Comparison of Bleach, Acetic Acid, and Other Topical Anti-Infective Treatments in Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis: A Retrospective Cohort Study on Antibiotic Exposure. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.T.; Abrams, M.; Tlougan, B.; Rademaker, A.; Paller, A.S. Treatment of Staphylococcus aureus Colonization in Atopic Dermatitis Decreases Disease Severity. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e808–e814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.E.; Schaffer, J.V.; Orlow, S.J.; Gao, Z.; Li, H.; Alekseyenko, A.V.; Blaser, M.J. Cutaneous Microbiome Effects of Fluticasone Propionate Cream and Adjunctive Bleach Baths in Childhood Atopic Dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 481–493.E8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, A.; Perez-Nazario, N.; Knowlden, S.A.; Chinchilli, E.; Grier, A.; Paller, A.; Gill, S.R.; De Benedetto, A.; Yoshida, T.; Beck, L.A. Bleach Baths Enhance Skin Barrier, Reduce Itch but Do Not Normalize Skin Dysbiosis in Atopic Dermatitis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Mitch, W.A. Drinking Water Disinfection Byproducts (DBPs) and Human Health Effects: Multidisciplinary Challenges and Opportunities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, C.M. Invited Perspective: Drinking Water Disinfection By-Products and Cancer-A Historical Perspective. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandova, J.; Snell, J.; Hua, A.; Dickinson, S.; Fimbres, J.; Wondrak, G.T. Topical hypochlorous acid (HOCl) blocks inflammatory gene expression and tumorigenic progression in UV-exposed SKH-1 high risk mouse skin. Redox Biol. 2021, 45, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ye, T.; Ye, C.; Wan, C.; Yuan, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Jiang, F.; Lovell, J.F.; Jin, H.; et al. Secretions from hypochlorous acid-treated tumor cells delivered in a melittin hydrogel potentiate cancer immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 9, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampiaw, R.E.; Yaqub, M.; Wontae, L. Electrolyzed water as a disinfectant: A systematic review of factors affecting the production and efficiency of hypochlorous acid. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 43, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafaurie, G.I.; Zaror, C.; Díaz-Báez, D.; Castillo, D.M.; De Ávila, J.; Trujillo, T.G.; Calderón-Mendoza, J. Evaluation of Substantivity of Hypochlorous Acid as an Antiplaque Agent: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2018, 16, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbargere Nagraj, S.; Eachempati, P.; Paisi, M.; Nasser, M.; Sivaramakrishnan, G.; Verbeek, J.H. Interventions to reduce contaminated aerosols produced during dental procedures for preventing infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 10, CD013686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, P.; Freitag, M.; Heidel, F.H.; Kocher, T.; Kramer, A. Antiseptic Efficacy of Two Mouth Rinses in the Oral Cavity to Identify a Suitable Rinsing Solution in Radiation- or Chemotherapy Induced Mucositis. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulin, C.; Magunacelaya-Barria, M.; Dahlén, G.; Kvist, T. Immediate Clinical and Microbiological Evaluation of the Effectiveness of 0.5% versus 3% Sodium Hypochlorite in Root Canal Treatment: A Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. Endod. J. 2020, 53, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouli, M.M.; Al Nesser, S.F.; Bshara, N.G.; AlMidani, A.N.; Comisi, J.C. Comparing the Efficacies of Two Chemo-Mechanical Caries Removal Agents (2.25% Sodium Hypochlorite Gel and Brix 3000), in Caries Removal and Patient Cooperation: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Dent. 2020, 93, 103280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkoutly, M.; Alnour, A.; Abu Hasna, A.; Nam, O.H.; Al Kurdi, S.; Bshara, N. Treatment Outcomes of Pulpotomy in Primary Molars Utilizing 2.25% Sodium Hypochlorite Gel: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Ramaglia, L.; Isola, G.; Blasi, A.; Salvi, G.E.; Sculean, A. Changes in Clinical Parameters Following Adjunctive Local Sodium Hypochlorite Gel in Minimally Invasive Nonsurgical Therapy (MINST) of Periodontal Pockets: A 6-Month Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 5331–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzarro, S.; Van der Velden, U.; Loos, B.G. Local Disinfection with Sodium Hypochlorite as Adjunct to Basic Periodontal Therapy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2016, 43, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrand Rudin, A.; Dahlstrand Rudin, A.; Ulin, C.; Kvist, T. The Use of 0.5% or 3% NaOCl for Irrigation during Root Canal Treatment Results in Similar Clinical Outcome: A 6-Year Follow-up of a Quasi-Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. Endod. J. 2024, 57, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.P.; Gupta, M.; Ahmed, H.; Tongya, R.; Sharma, D.; Chugh, B. Evaluation and Comparison between Formocresol and Sodium Hypochlorite as Pulpotomy Medicament: A Randomized Study. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2017, 18, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Cohen, C.L.; Galván, M.; Alonaizan, F.A.; Rich, S.K.; Slots, J. Gingival Bleeding on Probing: Relationship to Change in Periodontal Pocket Depth and Effect of Sodium Hypochlorite Oral Rinse. J. Periodontal Res. 2015, 50, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nardo, R.; Chiappe, V.; Gómez, M.; Romanelli, H.; Slots, J. Effects of 0.05% Sodium Hypochlorite Oral Rinse on Supragingival Biofilm and Gingival Inflammation. Int. Dent. J. 2012, 62, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galván, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Cohen, C.L.; Alonaizan, F.A.; Chen, C.T.-L.; Rich, S.K.; Slots, J. Periodontal Effects of 0.25% Sodium Hypochlorite Twice-Weekly Oral Rinse. A Pilot Study. J. Periodontal Res. 2014, 49, 696–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello-Gómez, A.; Navarro-Suárez, S.; Diosdado-Cano, J.M.; Azcárate-Velazquez, F.; Bargiela-Pérez, P.; Serrera-Figallo, M.A.; Torres-Lagares, D.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, J.L. Postoperative Effects on Lower Third Molars of Using Mouthwashes with Super-Oxidized Solution versus 0.2% Chlorhexidine Gel: A Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e716–e722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.Q.; Topilow, N.; Rong, A.; Persad, P.J.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, J.H.; Anagnostopoulos, A.G.; Lee, W.W. Comparison of Skin Antiseptic Agents and the Role of 0.01% Hypochlorous Acid. Aesthet. Surg. J. 2021, 41, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ş.; İlgin, V.E. Comparison of Antiseptics Containing Povidone-Iodine and Hypochlorous Acid Active Substances in Preventing Central Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infection in Intensive Care Units: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. DCCN 2025, 44, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccia, M.; Chakrokh, R.; Molinazzi, D.; Zanni, A.; Farruggia, P.; Sandri, F. Skin Antisepsis with 0.05% Sodium Hypochlorite before Central Venous Catheter Insertion in Neonates: A 2-Year Single-Center Experience. Am. J. Infect. Control 2018, 46, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.L.; Forbes, A.; Hammerman, W.A.; Lamberth, L.; Hulten, K.G.; Minard, C.G.; Mason, E.O. Randomized Trial of “Bleach Baths” plus Routine Hygienic Measures vs. Routine Hygienic Measures Alone for Prevention of Recurrent Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2014, 58, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.A.; Macias, J.H.; Macias, A.E.; Rodríguez, E.; Muñoz, J.M.; Mosqueda, J.L.; Ponce de Leon, S. Povidone-Iodine against Sodium Hypochlorite as Skin Antiseptics in Volunteers. Am. J. Infect. Control 2010, 38, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macias, J.H.; Arreguin, V.; Munoz, J.M.; Alvarez, J.A.; Mosqueda, J.L.; Macias, A.E. Chlorhexidine Is a Better Antiseptic than Povidone Iodine and Sodium Hypochlorite Because of Its Substantive Effect. Am. J. Infect. Control 2013, 41, 634–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S.A.; Camins, B.C.; Eisenstein, K.A.; Fritz, J.M.; Epplin, E.K.; Burnham, C.A.; Dukes, J.; Storch, G.A. Effectiveness of Measures to Eradicate Staphylococcus aureus Carriage in Patients with Community-Associated Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections: A Randomized Trial. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Fan, P.; Chu, J.; Yang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guo, C. A Contrast Study of Dermacyn on Enterocoely Irrigate to Control Intraoperative Infection. Minerva Chir. 2017, 72, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinç Gül, S.N.; Dilsiz, A.; Sağlık, İ.; Aydın, N.N. Effect of Oral Antiseptics on the Viral Load of SARS-CoV-2: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Dent. Med. Probl. 2022, 59, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panatto, D.; Orsi, A.; Bruzzone, B.; Ricucci, V.; Fedele, G.; Reiner, G.; Giarratana, N.; Domnich, A.; Icardi, G.; STX Study Group. Efficacy of the Sentinox Spray in Reducing Viral Load in Mild COVID-19 and Its Virucidal Activity against Other Respiratory Viruses: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial and an In Vitro Study. Viruses 2022, 14, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onghanseng, N.; Ng, S.M.; Halim, M.S.; Nguyen, Q.D. Oral Antibiotics for Chronic Blepharitis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 6, CD013697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertone, C.; Mollicone, A.; Russo, S.; Sasso, P.; Fasciani, R.; Riccardi, C.; Lizzano, M.; Ali Working Group, T. The Role of Hypochlorous Acid in the Management of Eye Infections: A Case Series. Drugs Context 2022, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklar, B.A.; Gervasio, K.A.; Leng, S.; Ghosh, A.; Chari, A.; Wu, A.Y. Management and Outcomes of Proteasome Inhibitor Associated Chalazia and Blepharitis: A Case Series. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, P.; Fam, A.; Tomar, A.; Garg, G.; Chin, K. COVID-19 Prophylaxis in Ophthalmology. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferček, I.; Ozretić, P.; Tambić-Andrašević, A.; Trajanoski, S.; Ćesić, D.; Jelić, M.; Geber, G.; Žaja, O.; Paić, J.; Lugović-Mihić, L.; et al. Comparison of the Skin Microbiota in the Periocular Region between Patients with Inflammatory Skin Diseases and Healthy Participants: A Preliminary Study. Life 2024, 14, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroman, D.; Mintun, K.; Epstein, A.; Brimer, C.; Patel, C.; Branch, J.; Najafi-Tagol, K. Reduction in Bacterial Load Using Hypochlorous Acid Hygiene Solution on Ocular Skin. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Wu, B.-C.; Cheng, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.-P.; Zhao, H.; Zeng, H.-M.; Qi, D.-F.; Ma, Z.-Y.; Li, J.-G.; et al. The Microbiome of Meibomian Gland Secretions from Patients with Internal Hordeolum Treated with Hypochlorous Acid Eyelid Wipes. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 7550090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bassiri, M.; Najafi, R.; Najafi, K.; Yang, J.; Khosrovi, B.; Hwong, W.; Barati, E.; Belisle, B.; Celeri, C.; et al. Hypochlorous Acid as a Potential Wound Care Agent: Part I. Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid: A Component of the Inorganic Armamentarium of Innate Immunity. J. Burns Wounds 2007, 6, e5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Liang, M.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.; Kuang, G. Hypochlorous Acid Can Be the Novel Option for the Meibomian Gland Dysfunction Dry Eye through Ultrasonic Atomization. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 8631038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tian, R.; Shi, C.; Wang, A. The Potential Effectiveness of an Ancient Chinese Herbal Formula Yupingfengsan for the Prevention of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Medinformatics 2024, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mencucci, R.; Morelli, A.; Favuzza, E.; Galano, A.; Roszkowska, A.M.; Cennamo, M. Hypochlorous Acid Hygiene Solution in Patients Affected by Blepharitis: A Prospective Randomised Study. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2023, 8, e001209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.; Giugliano, A.V.; Cesarano, I.; Di Perna, L.; Picardi, C. Conservative management of paediatric dacryocystitis: A collection of clinical experiences highlighting effectiveness and parental satisfaction. Drugs Context. 2025, 14, 2025-1-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bakacs, T. Healing of Severe Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus Within a Few Days: An Autobiographical Case Report. Cureus 2021, 13, e20303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-Y.; Tsai, H.-C.; Lee, S.S.-J.; Chen, Y.-S. Orbital Apex Syndrome: An Unusual Complication of Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostopoulos, A.G.; Rong, A.; Miller, D.; Tran, A.Q.; Head, T.; Lee, M.C.; Lee, W.W. 0.01% Hypochlorous Acid as an Alternative Skin Antiseptic: An In Vitro Comparison. Dermatol. Surg. 2018, 44, 1489–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fam, A.; Finger, P.; Tomar, A.; Garg, G.; Chin, K. Hypochlorous Acid Antiseptic Washout Improves Patient Comfort after Intravitreal Injection: A Patient Reported Outcomes Study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 68, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Auclin, F.; Rat, P.; Tuil, E.; Boureau-Andrieux, C.; Morel, C.; Laplace, O.; Cambourieu, C.; Limon, S.; Nordmann, J.P.; Laroche, L.; et al. Clinical evaluation of the ocular safety of Amukine 0.06% solution for local application versus povidone iodine (Bétadine) 5% solution for ocular irrigation) in preoperative antisepsis. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2002, 25, 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Inthavong, K.; Ge, Q.; Se, C.M.K.; Yang, W.; Tu, J.Y. Simulation of Sprayed Particle Deposition in a Human Nasal Cavity Including a Nasal Spray Device. J. Aerosol Sci. 2011, 42, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, T.; Elsherif, H.S.; Zulianello, L.; Plouin-Gaudon, I.; Landis, B.N.; Lacroix, J.S. Nasal Lavage with Sodium Hypochlorite Solution in Staphylococcus aureus Persistent Rhinosinusitis. Rhinology 2008, 46, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Inthavong, K.; Tian, Z.F.; Tu, J.Y.; Yang, W.; Xue, C. Optimising Nasal Spray Parameters for Efficient Drug Delivery Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Comput. Biol. Med. 2008, 38, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, J.S. Toward Personalized Nasal Surgery Using Computational Fluid Dynamics. Arch. Facial Plast. Surg. 2011, 13, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, J.A.; Funk, L.M.; Fountain, R.; Sedman, R. Quantifying the Distribution of Inhalation Exposure in Human Populations: Distribution of Minute Volumes in Adults and Children. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996, 104, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.J.; Min, H.J.; Chung, H.J.; Park, D.Y.; Seong, S.Y.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, C.H. Improved Outcomes after Low-Concentration Hypochlorous Acid Nasal Irrigation in Pediatric Chronic Sinusitis. Laryngoscope 2016, 126, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.S.; Kim, B.H.; Kang, S.H.; Lim, D.J. Low-Concentration Hypochlorous Acid Nasal Irrigation for Chronic Sinonasal Symptoms: A Prospective Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.S.; Liang, K.L. Effect of Hypochlorous Acid Nasal Spray as an Adjuvant Therapy after Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2022, 43, 103264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, H.J.; Bae, M.R.; Choi, W.R.; Jang, Y.J. Hypochlorous Acid Versus Saline Nasal Irrigation in Allergic Rhinitis: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2022, 36, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, L.A.; Hussain, A.; Barbhuiya, P.A.; Zaman, S.; Laskar, A.M.; Pathak, M.P.; Dutta, P.P.; Sen, S. Herbal Medicine for the Management of Wounds: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2025, 25, e18715265320593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedillo-Cortezano, M.; Martinez-Cuevas, L.R.; López, J.A.M.; Barrera López, I.L.; Escutia-Perez, S.; Petricevich, V.L. Use of Medicinal Plants in the Process of Wound Healing: A Literature Review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morguette, A.E.B.; Bartolomeu-Gonçalves, G.; Andriani, G.M.; Bertoncini, G.E.S.; Castro, I.M.d.; Spoladori, L.F.d.A.; Bertão, A.M.S.; Tavares, E.R.; Yamauchi, L.M.; Yamada-Ogatta, S.F. The Antibacterial and Wound Healing Properties of Natural Products: A Review on Plant Species with Therapeutic Potential against Staphylococcus aureus Wound Infections. Plants 2023, 12, 2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deyno, S.; Mtewa, A.G.; Abebe, A.; Hymete, A.; Makonnen, E.; Bazira, J.; Alele, P.E. Essential oils as topical anti-infective agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2019, 47, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belete, B.B.; Ozkan, J.; Kalaiselvan, P.; Willcox, M. Clinical Potential of Essential Oils: Cytotoxicity, Selectivity Index, and Efficacy for Combating Gram-Positive ESKAPE Pathogens. Molecules 2025, 30, 3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robson, M.C.; Payne, W.G.; Ko, F.; Mentis, M.; Donati, G.; Shafii, S.M.; Culverhouse, S.; Wang, L.; Khosrovi, B.; Najafi, R.; et al. Hypochlorous Acid as a Potential Wound Care Agent: Part II. Stabilized Hypochlorous Acid: Its Role in Decreasing Tissue Bacterial Bioburden and Overcoming the Inhibition of Infection on Wound Healing. J. Burns Wounds 2007, 6, e6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sakarya, S.; Gunay, N.; Karakulak, M.; Ozturk, B.; Ertugrul, B. Hypochlorous Acid: An Ideal Wound Care Agent With Powerful Microbicidal, Antibiofilm, And Wound Healing Potency. Wounds 2014, 26, 342–350. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo-Soledad, A.; Smesrud, L.; Bandaru, S.R.S.; Hernandez, D.; Mehare, M.; Mahmoud, S.; Matange, V.; Rao, B.N.C.; Balcom, P.; Omole, D.O.; et al. Low-Cost, Local Production of A Safe and Effective Disinfectant for Resource-Constrained Communities. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Ma, S.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, J. Current Progress, Opportunities and Challenges of Developing Green Disinfectants for the Remediation of Disinfectant Emerging Contaminants. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 42, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessi, A.; Marghella, G.; Bruni, S.; Ubaldini, A.; Tamburini, E. HClO as a Disinfectant: Assessment of Chemical Sustainability Aspects by a Morphological Study. Chemistry 2025, 7, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamatsu, Y.; Ikeda, H.; Nagamatsu, H. Long-Term Storage Stability of Neutral Electrolyzed Water by Two-Stage Electrolysis: Optimal Storage Conditions for Intraoral Use. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.K.; Hiorth, M.; Rongved, P. A novel and stable formulation of powdered high-assay calcium hypochlorite as a solid precursor of the antimicrobial compound hypochlorous acid: A preformulation study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 113, 107292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, E.J.; Mallow, P.J.; Noble, A.J.; Foster, K. Cost Analysis of Pure Hypochlorous Acid Preserved Wound Cleanser versus Mafenide for the Irrigation of Burn Wounds. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2024, 16, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, R.; Ahmed, S. Exploring the Efficacy of Hypochlorous Acid as a Cost Effective Environmental Decontaminant in Dentistry: A Scoping Review. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2025, 28, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | Participants (Number, Diagnosis) | Results/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Valdová, V., 2025 [38] | 237 patients with acute and chronic wounds | DebriEcaSan Alfa (neutral electrolyzed water solution) is a safe and effective adjunct in the treatment of acute/chronic wounds, demonstrating significant improvements in wound healing parameters. |

| Burian, E.A., 2022 [41] | 20 healthy participants | Stabilized HOCl solution showed significant antimicrobial activity and accelerated wound healing, supporting its potential as an effective treatment for acute wounds. |

| Hiebert, J.M., 2016 [43] | 17 adult patients with chronic open wounds | Ultrasound-assisted debridement with HOCl irrigation was more effective than saline in reducing bacterial regrowth in chronic open wounds. |

| Fazli, M.M., 2024 [44] | 20 patients with chronic leg wounds in the first phase, 8 patients in the second pha | The SoftOx Biofilm Eradicator (composed of HOCl and acetic acid) was safe and well-tolerated by patients with chronic leg wounds. It showed promising, immediate antimicrobial effects and dose-dependent trends toward wound size reduction |

| Herruzo, R., 2023 [55] | 220 patients with 346 chronic ulcers of various etiologies | Combined treatment with liquid and gel formulations of HOCl significantly improved healing outcomes in chronic ulcers and reduced the risk of infection. |

| Stough D., 2023 [60] | 35 hair restoration surgery patients | Topical stabilized HOCl spray significantly reduced erythema and pruritus (with high patient compliance with treatment), and no tissue necrosis, supporting its valuableness in wound healing and postoperative care for hair restoration surgery. |

| Burian, E.A., 2023 [61] | 12 split-skin graft transplantation patients | Stabilized HOCl in acetic buffer (HOCl + buffer) was well tolerated and showed promising wound healing, and had antimicrobial effects on, acute wounds, despite transient pain during treatment. |

| Selkon, J.B., 2006 [62] | 30 patients with chronic venous leg ulcers | HOCl washes are an effective adjunctive therapy for chronic venous leg ulcers, enhancing healing and providing rapid pain relief. |

| Niezgoda, J.A., 2010 [63] | 31 patients with venous or mixed venous/arterial leg ulcers | Vashe Wound Therapy significantly improved healing outcomes in patients with chronic leg ulcers, with 86% of lesions healed and a 47% reduction in size of non-healed wounds; it completely eliminated wound odor and resolved patient-reported pain. |

| Eliasson, B., 2021 [64] | 57 patients with a lower extremity ulcer covered with devitalized tissue | Amino acid–buffered hypochlorite is effective and well-tolerated in treating hard-to-heal lower extremity ulcers. It reduces devitalized tissue, promoting wound healing and improving overall wound condition. |

| Serena, T.E., 2022 [65] | 16 patients with hard-to-heal ulcers | Patients treated with NaOCl showed greater reductions in wound size and bacterial load compared to normal saline. |

| Lindfors J., 2004 [66] | 11 patients with 18 wounds | Wounds treated with NaOCl cleanser consistently showed a reduction in bioburden and wound size compared to those treated with normal saline. |

| Assadian, O., 2018 [67] | 260 patients with 299 chronic wounds | Wound irrigation with antiseptic solutions, particularly those containing hypochlorite/HOCl or agents like polihexanide, octenidine, or povidone-iodine, significantly reduced bacterial burden compared to saline. |

| Ricci, E., 2021 [68] | 31 patients with hard-to-heal ulcers | Long-term use of HOCl oxidizing solution in combination with standard care was effective in promoting healing and improving wound conditions in patients with hard-to-heal ulcers. |

| Mohd, A.R., 2010 [69] | 178 patients who underwent sternotomy | Dermacyn was safe and more effective as a wound-irrigation agent than povidone-iodine for preventing sternotomy wound infections. |

| Dalla Paola, L., 2006 [70] | 218 patients with diabetic foot lesions | Super-oxidized solution is more effective and safer than povidone-iodine in treating infected diabetic foot lesions. It reduced bacterial load and accelerated healing time. |

| Martínez-De Jesús, F.R., 2007 [71] | 45 patients with infected diabetic foot ulcerations | Neutral pH superoxidised aqueous solution is more effective and less toxic than conventional disinfectants in managing infected diabetic foot ulcers; it improves infection control, reduces odor and erythema, and promotes wound healing. |

| Piaggesi, A., 2010 [72] | 40 patients with postsurgical infected diabetic foot lesions | Dermacyn® Wound Care is more effective than povidone iodine in promoting healing of wide postsurgical lesions in infected diabetic foot. |

| Author, Year | Participants (Number, Diagnosis) | Results/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Majewski, S., 2019 [84] | 50 children with moderate to severe AD and S. aureus skin colonization | Daily use of a 0.006% NaOCl body wash improved all outcome measures for S. aureus colonized AD in infants, children, and adolescents. |

| Hon, K.L., 2016 [85] | 40 patients with moderate to severe AD | A regime of diluted bleach baths (4–2 times weekly) did not show superiority over water baths in terms of reducing S. aureus colonization or significantly improving AD severity. |

| Ryan, C., 2013 [87] | 18 children with moderate to severe AD | Treatment with a cleansing body wash containing NaOCl led to a significant reduction in AD severity (scores IGA and BSA); the body wash was easier to use than traditional bleach baths. |

| Wong, S., 2013 [88] | 36 patients (aged 2–30 years old) with moderate to severe AD | AD patients who took diluted bleach baths showed significant reductions in AD severity (EASI scores) and Staphylococcus aureus density, indicating clinical improvement. |

| Asch, S., 2019 [89] | 753 children with AD | Diluted bleach baths or topical diluted acetic acid were not associated with decreased systemic antibiotic exposure for AD superinfections in the treatment of pediatric AD. |

| Huang, J.T., 2009 [90] | 31 pediatric patients with moderate to severe AD and secondary bacterial infections | Chronic use of diluted bleach baths with intermittent intranasal application of mupirocin ointment decreased clinical AD severity in patients with clinical signs of secondary bacterial infections. |

| Stolarczyk, A., 2023 [92] | 15 adults with AD and 5 healthy controls | Bleach baths improved AD severity, patient-reported pruritus, sleep quality, and physiological measures of skin barrier function in adults with AD, but they had no effect on qualitative or quantitative measures of cutaneous S. aureus. |

| Gonzalez, M.E., 2016 [93] | 21 children with AD and 14 healthy controls | Both treatment groups (topical corticosteroids alone and corticosteroids plus bleach baths) saw significantly improved AD severity and restored microbial diversity on lesional skin, with no added clinical/microbiologic benefit observed from bleach baths. |

| Author, Year | Participants (Number, Diagnosis) | Results/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Lin, Y.C., 2023 [12] | 53 patients with periodontal disease, 30 healthy controls | 100 ppm HOCl mouthwash significantly reduced total salivary bacterial count and the abundance of Staphylococcus aureus in patients with periodontal disease. |

| Lafaurie, G.I., 2018 [98] | 75 healthy participants | HOCl mouthwash temporarily reduced bacterial counts in saliva but showed no lasting substantivity, with levels returning to baseline within one hour. |

| Zwicker, P., 2023 [100] | 20 orally healthy participants | Both Granudacyn® and Octenidol® mouth rinses significantly reduced bacterial counts on the buccal mucosa and in saliva. Octenidine was more potent, but its cytotoxicity makes Granudacyn® a safer option for patients with sensitive oral mucosa during cancer therapy. |

| Ulin, C., 2020 [101] | 298 patients with endodontic diagnoses and root canal treatment | Increasing NaOCl concentration for irrigation during root canal preparation from 0.5% to 3% did not significantly affect the number of positive bacterial cultures or the frequency/intensity of postoperative pain. Patients treated with 3% NaOCl experienced a significantly higher postoperative swelling incidence. |

| Alkhouli, M.M., 2020 [102] | 32 children with proximal caries of primary maxillary molars | CMCR agents like Brix 3000 and 2.25% NaOCl gel effectively removed carious dentine in primary teeth. Although conventional rotary treatment was faster, it caused significantly more pain. |

| Karkoutly, M., 2025 [103] | 24 children with 48 carious first primary molars | The use of 2.25% NaOCl gel in pulpotomy of primary molars improved odontoblastic integrity, dentin bridge formation, and overall treatment outcomes without increasing adverse effects. |

| Iorio-Siciliano, V., 2021 [104] | 40 untreated patients with severe/advanced periodontitis | Adjunctive use of NaOCl gel may enhance the effectiveness of MINST of periodontal pockets. |

| Bizzarro, S., 2016 [105] | 110 patients with chronic periodontitis | Local disinfection with NaOCl, with or without systemic antimicrobials, did not provide additional long-term clinical or microbiological benefits compared to basic periodontal therapy alone. |

| Dahlstrand Rudin, A., 2024 [106] | 298 patients who underwent root canal treatment | Root canal irrigation with either 0.5% or 3% NaOCl showed comparable long-term clinical outcomes after 5–7 years, with no significant differences in tooth survival, retreatment, or apical periodontitis. |

| Chauhan, S.P., 2017 [107] | 40 children with carious primary molars who underwent pulpotomy | Both FC and 5% NaOCl showed high clinical success rates at 3 and 6 months, with slightly lower radiographic success for NaOCl; NaOCl is an effective alternative as a pulpotomy medicament for primary molars. |

| Gonzalez, S., 2015 [108] | 12 patients with periodontitis | Twice-weekly oral rinsing with 0.25% NaOCl significantly reduced bleeding on probing, even in deep unscaled pockets (persistent gingival bleeding on probing was associated with a higher risk of periodontal breakdown). |

| De Nardo, R., 2012 [109] | 40 healthy participants | 0.05% NaOCl mouth rinse significantly reduced supragingival biofilm, gingival inflammation, and bleeding on probing (compared to water); extrinsic brown tooth staining was observed in all participants using NaOCl |

| Galván, M., 2014 [110] | 30 patients with periodontitis | Twice-weekly rinsing with 0.25% NaOCl, compared with water, significantly reduced dental plaque and gingival bleeding |

| Coello-Gómez, A., 2018 [111] | 20 patients with symmetrically impacted bilateral lower third molars | Both super-oxidized solution and 0.2% chlorhexidine gel mouthwashes enhanced postoperative recovery after lower third molar extractions. |

| Author, Year | Participants (Number, Diagnosis) | Results/Conclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Parcells, J.P., 2009 [48] | 1063 patients who underwent appendectomy | Abdominal irrigation with an imipenem 1 mg/mL antibiotic solution significantly reduced postoperative surgical site infections compared to normal saline and Dakin’s solution (NaOCl). |

| Tran, A.Q., 2021 [112] | 21 adults | Chlorhexidine gluconate as a skin antiseptic agent showed less bacterial growth, while HOCl, isopropyl alcohol, and povidone iodine showed no significant differences in bactericidal effects. |

| Yılmaz, Ş., 2025 [113] | 60 patients in intensive care units | Catheter dressings with HOCl significantly reduced the incidence of central venous catheter-related bloodstream infections and signs of infection at the catheter exit site compared to povidone-iodine dressings. |

| Ciccia, M., 2018 [114] | 105 infants who underwent central venous catheter placement | No evidence of skin toxicity in neonates undergoing central venous catheter placement with 0.05% NaOCl for skin antisepsis. |

| Kaplan, S.L., 2014 [115] | 482 children treated for suspected S. aureus skin and soft tissue infection or invasive infection | Bleach baths combined with hygiene education showed a modest but non-significant reduction in recurrent MRSA skin and soft tissue infection compared to hygiene education alone, with no observed adverse effects. |

| Alvarez, J.A., 2010 [116] | 48 healthy participants | Both 10% povidone-iodine and 10% NaOCl significantly reduced bacterial counts compared to baseline controls (no significant difference in antiseptic efficacy was observed between the two agents). |

| Macias, J.H., 2013 [117] | 30 healthy participants | Chlorhexidine gluconate in isopropyl alcohol, NaOCl, and povidone-iodine showed comparable antiseptic efficacy for short-term procedures; only chlorhexidine showed a prolonged effect. |

| Fritz, S.A., 2011 [118] | 300 patients with community-onset skin and soft-tissue infection and S. aureus colonization | Diluted bleach baths combined with intranasal mupirocin and hygiene education showed the highest and most sustained reduction in S. aureus colonization. Persistent recurrence of skin and soft-tissue infection highlights the need to address additional risk factors beyond S. aureus colonization. |

| Liu, J., 2017 [119] | 212 patients with intestinal perforation who underwent opened surgical repair or partial intestinal resection | The use of Dermacyn for intraoperative peritoneal lavage effectively reduced the risk of infection due to its broad-spectrum bactericidal activity. |

| Sevinç Gül, S.N., 2022 [120] | 75 patients hospitalized in the COVID-19 ward | After gargling with HOCl or povidone-iodine, no significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2 viral load was seen, which suggests that antiseptic mouth rinses may not play a meaningful role in preventing viral transmission. |

| Panatto, D., 2022 [121] | 57 patients with mild COVID-19 | Sentinox spray may accelerate viral clearance in mild COVID-19 patients (which demonstrated a broad virucidal spectrum) and was safe and well tolerated in both clinical and in vitro settings. |

| Ophthalmology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Zhang, H., 2023 [34] | 67 patients with blepharitis | In patients with blepharitis topical 0.01% HOCl delivered via ultrasonic atomization is a safe and effective method for eyelid hygiene and provides improvements in ocular surface health and meibomian gland function. |

| Wang, H., 2023 [37] | 96 patients with fungal keratitis | The use of HOCl solution in patients with blepharitis and dry eye disease causes significant improvements in tear film stability, ocular surface symptoms, and reduction in bacterial load, with outcomes superior to those observed with hyaluronic acid wipes. |

| Yang, S., 2022 [128] | 8 patients with internal hordeolum | In patients with internal hordeolum, eyelid cleaning with HOCl wipes did not alter the overall biodiversity of meibomian gland secretions; the wipes reduced harmful bacterial pathogens while promoting beneficial symbiotic bacteria. |

| Mencucci, R., 2023 [132] | 48 patients with blepharitis and mild to moderate dry eye disease | The use of HOCl solution in patients with blepharitis and dry eye disease causes significant improvements in tear film stability, ocular surface symptoms, and reduction in bacterial load, with outcomes superior to those observed with hyaluronic acid wipes. |

| Otorhinolaryngology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Raza T., 2008 [140] | 22 patients with persistent rhinosinusitis (S. aureus infection symptomatic carriers | 0.05% NaOCl solution for nasal irrigation reduces symptoms, improves condition, and decreases airway resistance |

| Cho, H.J., 2016 [144] | 37 children with rhinosinusitis | Both HOCl and isotonic saline nasal irrigation significantly improved total symptom scores in pediatric chronic rhinosinusitis. X-ray findings showed greater improvement in the HOCl group. |

| Yu, M.S., 2017 [145] | 43 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis | Low-concentration HOCl nasal irrigation significantly improved chronic rhinosinusitis symptoms compared to saline irrigation (endoscopic scores and bacterial culture differences were not significant). |

| Jiang, R.S., 2022 [146] | 78 FESS patients with chronic rhinosinusitis | HOCl nasal spray demonstrated similar effectiveness to normal saline nasal irrigation in post-FESS care, resulting in significant improvement in endoscopic scores. |

| Kim, H.C., 2022 [147] | 139 patients with perennial allergic rhinitis | Low-concentration HOCl nasal irrigation significantly reduced allergic rhinitis symptoms (without causing adverse effects), but it did not provide additional symptom improvement compared to saline nasal irrigation. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Haralović, V.; Mokos, M.; Špoljar, S.; Dolački, L.; Šitum, M.; Lugović-Mihić, L. Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Insights and Experience in Dermatology, Surgery, Dentistry, Ophthalmology, Rhinology, and Other Specialties. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122921

Haralović V, Mokos M, Špoljar S, Dolački L, Šitum M, Lugović-Mihić L. Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Insights and Experience in Dermatology, Surgery, Dentistry, Ophthalmology, Rhinology, and Other Specialties. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122921

Chicago/Turabian StyleHaralović, Vanda, Mislav Mokos, Sanja Špoljar, Lorena Dolački, Mirna Šitum, and Liborija Lugović-Mihić. 2025. "Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Insights and Experience in Dermatology, Surgery, Dentistry, Ophthalmology, Rhinology, and Other Specialties" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122921

APA StyleHaralović, V., Mokos, M., Špoljar, S., Dolački, L., Šitum, M., & Lugović-Mihić, L. (2025). Hypochlorous Acid: Clinical Insights and Experience in Dermatology, Surgery, Dentistry, Ophthalmology, Rhinology, and Other Specialties. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2921. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122921