Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Insights on the Disease Biology and Impact on Leukemic Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Conventional and Molecular Cytogenetic Analysis

3. Results

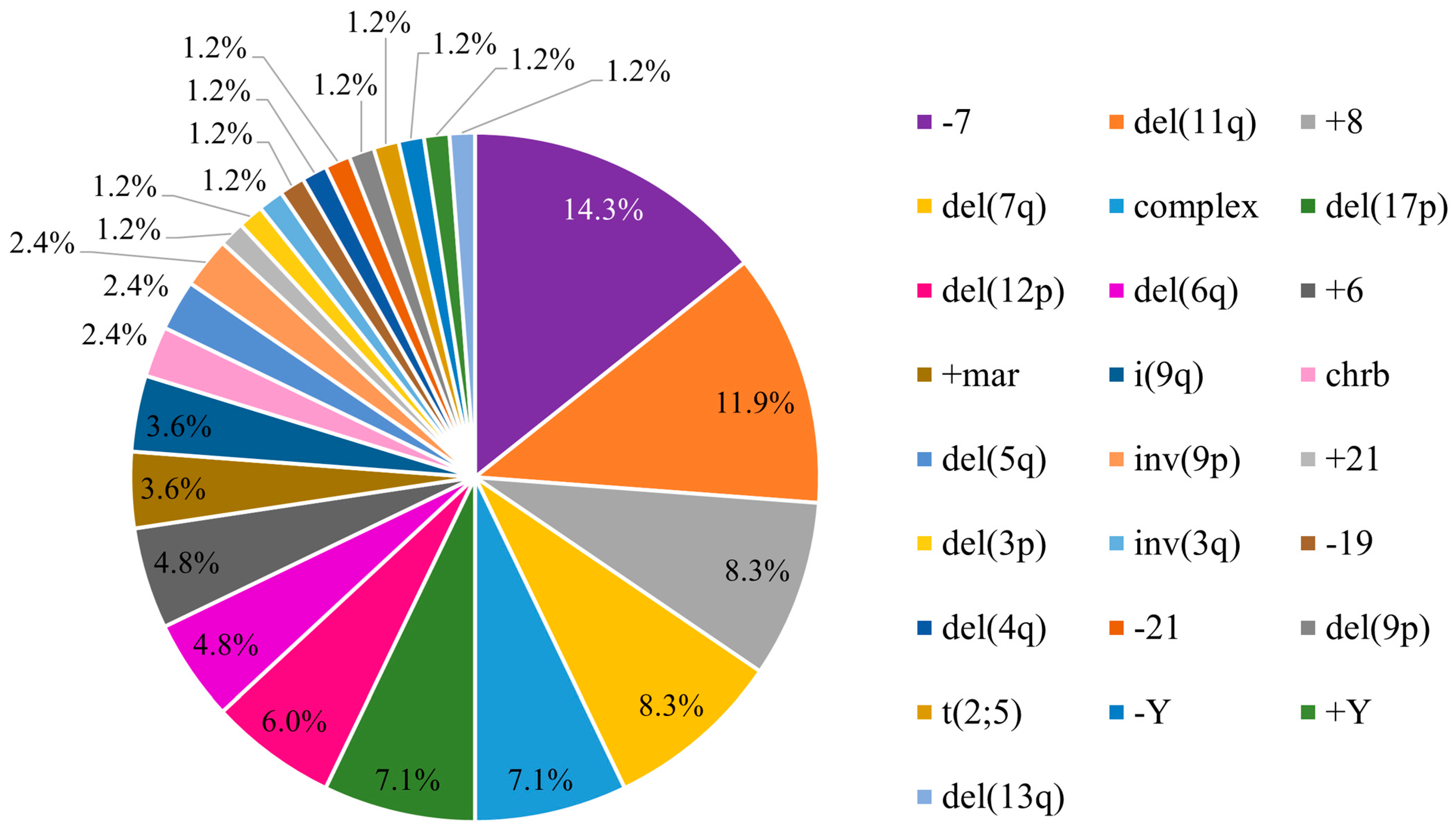

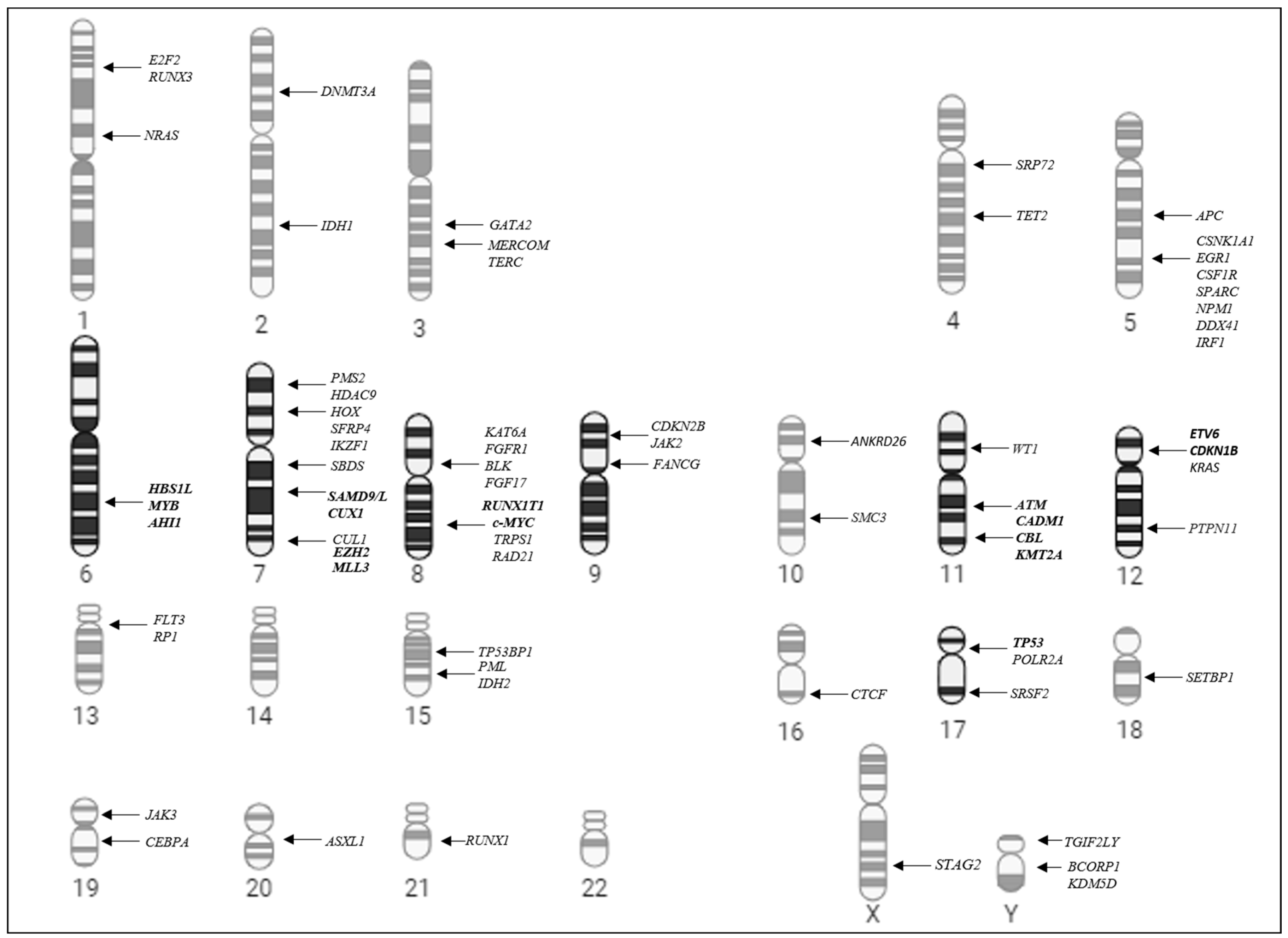

3.1. Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome

3.2. Distribution of the Chromosomal Pattern of pMDS Patients According to Subtypes

3.3. Cytogenetic Risk Groups According to IPSS-R

3.4. Association Between the Chromosomal Pattern and Evolution from pMDS to AML

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudelius, M.; Weinberg, O.K.; Niemeyer, C.M.; Shimamura, A.; Calvo, K.R. The International Consensus Classification (ICC) of hematologic neoplasms with germline predisposition, pediatric myelodysplastic syndrome, and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Virchows Arch. 2023, 482, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-C.; Geyer, J.T. Pediatric Hematopathology in the Era of Advanced Molecular Diagnostics: What We Know and How We Can Apply the Updated Classifications. Pathobiology 2024, 91, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arber, D.A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Borowitz, M.J.; Calvo, K.R.; Kvasnicka, H.-M.; Wang, S.A.; Bagg, A.; Barbui, T.; Branford, S.; et al. International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: Integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 2022, 140, 1200–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.; Hammad, M.; Hafez, H.; Salem, S.; Soliman, S.; Ghazal, S.; Hassanain, O.; El-Haddad, A. Outcome and factors affecting survival of childhood myelodysplastic syndrome; single centre experience. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. J. 2019, 4, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovatel, V.L.; da Silva, B.F.; Rodrigues, E.F.; da Rosa Borges, M.L.R.; de Cássia Barbosa Tavares, R.; Bueno, A.P.S.; da Costa, E.S.; de Jesus Marques Salles, T.; de Souza Fernandez, T. Association between Leukemic Evolution and Uncommon Chromosomal Alterations in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 16, e2024003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, K.; Manabe, A.; Taketani, T.; Kikuchi, A.; Nakahata, T.; Hayashi, Y. Cytogenetics and clinical features of pediatric myelodysplastic syndrome in Japan. Int. J. Hematol. 2014, 100, 478–484, Erratum in Int. J. Hematol. 2015, 102, 249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-015-1834-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panani, A.D.; Roussos, C. Cytogenetic aspects of adult primary myelodysplastic syndromes: Clinical implications. Cancer Lett. 2006, 235, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, H.; Nagamachi, A.; Inaba, T. −7/7q− syndrome in myeloid-lineage hematopoietic malignancies: Attempts to understand this complex disease entity. Oncogene 2015, 34, 2413–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasle, H. Myelodysplastic and myeloproliferative disorders of childhood. Hematology. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2016, 2016, 598–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarski, M.W.; Sahoo, S.S.; Niemeyer, C.M. Monosomy 7 in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Hematol. Oncol Clin. N. Am. 2018, 32, 729–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, E.; Takahashi, K.; Wang, X.; Cornelison, A.M.; Abruzzo, L.; Kadia, T.; Borthakur, G.; Estrov, Z.; O’BRien, S.; Mallo, M.; et al. Acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with IPSS defined lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome is associated with poor prognosis and transformation to acute myelogenous leukemia. Am. J. Hematol. 2013, 88, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, P.; Cox, C.; LeBeau, M.M.; Fenaux, P.; Morel, P.; Sanz, G.; Sanz, M.; Vallespi, T.; Hamblin, T.; Oscier, D.; et al. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 1997, 89, 2079–2088, Erratum in Blood 1998, 91, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, D.C.; de Souza Fernandez, C.; Camargo, A.; Apa, A.G.; da Costa, E.S.; Bouzas, L.F.; Abdelhay, E.; de Souza Fernandez, T. Cytogenetic as an important tool for diagnosis and prognosis for patients with hypocellular primary myelodysplastic syndrome. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 542395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, P.L.; Tuechler, H.; Schanz, J.; Sanz, G.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Solé, F.; Bennett, J.M.; Bowen, D.; Fenaux, P.; Dreyfus, F.; et al. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 2012, 120, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, V.; Hirabayashi, S.; Karow, A.; Wehrle, J.; Kozyra, E.J.; Nienhold, R.; Ruzaike, G.; Lebrecht, D.; Yoshimi, A.; Niewisch, M.; et al. Mutational landscape in children with myelodysplastic syndromes is distinct from adults: Specific somatic drivers and novel germline variants. Leukemia 2017, 31, 759–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, S.; Kato, M.; Watanabe, K.; Ishimaru, S.; Hasegawa, D.; Noguchi, M.; Hama, A.; Sato, M.; Koike, T.; Iwasaki, F.; et al. Prognostic value of the revised International Prognostic Scoring System five-group cytogenetic abnormality classification for the outcome prediction of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric myelodysplastic syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2021, 56, 3016–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein-Peterson, Z.D.; Spitzer, B.; Derkach, A.; Arango, J.E.; McCarter, J.G.; Medina-Martínez, J.S.; McGovern, E.; Farnoud, N.R.; Levine, R.L.; Tallman, M.S. De Novo myelodysplastic syndromes in patients 20–50 years old are enriched for adverse risk features. Leuk. Res. 2022, 117, 106857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Fernandez, T.; Alvarenga, T.F.; de Kós, E.A.A.; Lovatel, V.L.; de Cássia Tavares, R.; da Costa, E.S.; de Souza Fernandez, C.; Abdelhay, E. Aberrant Expression of EZH2 in Pediatric Patients with Myelodysplastic Syndrome: A Potential Biomarker of Leukemic Evolution. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3176565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göhring, G.; Michalova, K.; Beverloo, H.B.; Betts, D.; Harbott, J.; Haas, O.A.; Kerndrup, G.; Sainati, L.; Bergstraesser, E.; Hasle, H.; et al. Complex karyotype newly defined: The strongest prognostic factor in advanced childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 2010, 116, 3766–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan-Jordan, J.; Hastings, R.J.; Moore, S. (Eds.) ISCN 2020: An International System for Human Cytogenomic Nomenclature; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, H.; Manabe, A.; Kojima, S.; Tsuchida, M.; Hayashi, Y.; Ikuta, K.; Okamura, J.; Koike, K.; Ohara, A.; Ishii, E.; et al. Myelodysplastic syndrome in childhood: A retrospective study of 189 patients in Japan. Leukemia 2001, 15, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, J.R.; Ma, J.; Lamprecht, T.; Walsh, M.; Wang, S.; Bryant, V.; Song, G.; Wu, G.; Easton, J.; Kesserwan, C.; et al. The genomic landscape of pediatric myelodysplastic syndromes. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanz, J.; Tüchler, H.; Solé, F.; Mallo, M.; Luño, E.; Cervera, J.; Granada, I.; Hildebrandt, B.; Slovak, M.L.; Ohyashiki, K.; et al. New comprehensive cytogenetic scoring system for primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia after MDS derived from an international database merge. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasle, H.; Baumann, I.; Bergsträsser, E.; Fenu, S.; Fischer, A.; Kardos, G.; Kerndrup, G.; Locatelli, F.; Rogge, T.; Schultz, K.R.; et al. The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) for childhood myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML). Leukemia 2004, 18, 2008–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.; Tuechler, H.; Greenberg, P.L.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Ossa, J.E.A.; Nannya, Y.; Devlin, S.M.; Creignou, M.; Pinel, P.; Monnier, L.; et al. Molecular International Prognostic Scoring System for Myelodysplastic Syndromes. NEJM Evid. 2022, 1, EVIDoa2200008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galaverna, F.; Ruggeri, A.; Locatelli, F. Myelodysplastic syndromes in children. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2018, 30, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, K.; Onozawa, M.; Miyashita, N.; Yokohata, E.; Yoshida, M.; Kanaya, M.; Kosugi-Kanaya, M.; Takemura, R.; Takahashi, S.; Sugita, J.; et al. Cytogenetically Unrelated Clones in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Showing Different Responses to Chemotherapy. Case Rep. Hematol. 2016, 2016, 2373902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellagatti, A.; Boultwood, J. The molecular pathogenesis of the myelodysplastic syndromes. Eur. J. Haematol. 2015, 95, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boultwood, J. CUX1 in leukemia: Dosage matters. Blood 2013, 121, 869–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, T.; Honda, H.; Matsui, H. The enigma of monosomy 7. Blood 2018, 131, 2891–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammenga, J. Of gains and losses: SAMD9/SAMD9L and monosomy 7 in myelodysplastic syndrome. Exp. Hematol. 2024, 134, 104217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saumell, S.; Solé, F.; Arenillas, L.; Montoro, J.; Valcárcel, D.; Pedro, C.; Sanzo, C.; Luño, E.; Giménez, T.; Arnan, M.; et al. Trisomy 8, a Cytogenetic Abnormality in Myelodysplastic Syndromes, Is Constitutional or Not? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, S.; Spassov, B.; Nikolova, V.; Christov, I.; Tzvetkov, N.; Simeonova, M. Is Amplification of cMYC, MLL and RUNX1 Genes in AML and MDS Patients with Trisomy 8, 11 and 21 a Factor for a Clonal Evolution in the Karyotype? Cytol. Genet. 2015, 49, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, L.; Jiang, L.; Luo, Y.; Lin, P.; Yang, W.; Ren, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhou, X.; Mei, C.; et al. Clinical significance of cytogenetic and molecular genetic abnormalities in 634 Chinese patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 1759–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toribio-Castelló, S.; Castaño, S.; Villaverde-Ramiro, Á.; Such, E.; Arnán, M.; Solé, F.; Díaz-Beyá, M.; Díez-Campelo, M.; del Rey, M.; González, T.; et al. Mutational Profile Enables the Identification of a High-Risk Subgroup in Myelodysplastic Syndromes with Isolated Trisomy 8. Cancers 2023, 15, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtaneva, K.; Wright, F.A.; Tanner, S.M.; Yuan, B.; Lemon, W.J.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Bloomfield, C.D.; de la Chapelle, A.; Krahe, R. Expression profiling reveals fundamental biological differences in acute myeloid leukemia with isolated trisomy 8 and normal cytogenetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, T.D.S.; Silva, M.L.M.; De Souza, J.; De Paula, M.T.M.; Abdelhay, E. C-MYC amplification in a case of progression from MDS to AML (M2). Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1996, 86, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafage-Pochitaloff, M.; Gerby, B.; Baccini, V.; Largeaud, L.; Fregona, V.; Prade, N.; Juvin, P.-Y.; Jamrog, L.A.; Bories, P.; Hébrard, S.; et al. The CADM1 tumor suppressor gene is a major candidate gene in MDS with deletion of the long arm of chromosome 11. Blood Adv. 2022, 6, 386–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Burmeister, T.; Gröger, D.; Tsaur, G.; Fechina, L.; Renneville, A.; Sutton, R.; Venn, N.C.; Emerenciano, M.; Pombo-de-Oliveira, M.S.; et al. The MLL recombinome of acute leukemias in 2017. Leukemia 2018, 32, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahjahani, M.; Hadad, E.H.; Azizidoost, S.; Nezhad, K.C.; Shahrabi, S. Complex karyotype in myelodysplastic syndromes: Diagnostic procedure and prognostic susceptibility. Oncol. Rev. 2019, 13, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynt, E.; Bisht, K.; Sridharan, V.; Ortiz, M.; Towfic, F.; Thakurta, A. Prognosis, Biology, and Targeting of TP53 Dysregulation in Multiple Myeloma. Cells 2020, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharry, S.E.; Walker, C.J.; Liyanarachchi, S.; Mehta, S.; Patel, M.; Bainazar, M.A.; Huang, X.; Lankenau, M.A.; Hoag, K.W.; Ranganathan, P.; et al. Dissection of the Major Hematopoietic Quantitative Trait Locus in Chromosome 6q23.3 Identifies miR-3662 as a Player in Hematopoiesis and Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborelli, M.; Tibiletti, M.; Martin, V.; Pozzi, B.; Bertoni, F.; Capella, C. Chromosome band 6q deletion pattern in malignant lymphomas. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2006, 165, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Kwon, M.-J.; Lee, S.-T.; Woo, H.-Y.; Park, H.; Kim, S.-H. Analysis of acute myeloid leukemia in Korean patients with sole trisomy 6. Ann. Lab. Med. 2014, 34, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.N.; Varterasian, M.L.; Dobin, S.M.; McConnell, T.S.; Wolman, S.R.; Rankin, C.; Willman, C.L.; Head, D.R.; Slovak, M.L. Trisomy 6 as a primary karyotypic aberration in hematologic disorders. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1998, 106, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braulke, F.; Müller-Thomas, C.; Götze, K.; Platzbecker, U.; Germing, U.; Hofmann, W.; Giagounidis, A.A.N.; Lübbert, M.; Greenberg, P.L.; Bennett, J.M.; et al. Frequency of del(12p) is commonly underestimated in myelodysplastic syndromes: Results from a German diagnostic study in comparison with an international control group. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 2015, 54, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olney, H.J.; Le Beau, M.M. Myelodysplastic syndromes. In Myelodysplastic Syndromes; Heim, S., Mitelman, F., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovatel, V.L.; Ferreira, G.M.; da Silva, B.F.; de Souza Torres, R.; de Cássia Barbosa da Silva Tavares, R.; Bueno, A.P.S.; Abdelhay, E.; de Souza Fernandez, T. Identification of Genetic Variants Using Next-Generation Sequencing in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: From Disease Biology to Clinical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| MDS | 193 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 114 (59%) |

| Female | 79 (41%) |

| Mean age (range) | 9 (3 months–18 years) |

| (0–2 years) | 34 (17.6%) |

| (3–11years) | 92 (47.7%) |

| (12–18 years) | 67 (34.7%) |

| Number of cytopenias | |

| 1 | 57 (29.5%) |

| 2 | 71 (36.8%) |

| 3 | 65 (33.7%) |

| MDS Subtypes | |

| RCC | 145 (66%) |

| MDS-EB | 48 (21.8%) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Normal | 109 (56.5%) |

| Abnormal | 84 (43.5%) |

| Evolution from MDS → AML | |

| No | 151 (78%) |

| Yes | 42 (22%) |

| Cytogenetic Risk IPSS-R | Frequency %/(Number of Patients) | Evolution MDS to AML |

|---|---|---|

| VERY GOOD | 5.7% (11/193) | 64% (7/11) |

| GOOD | 60.1% (116/193) | 6% (7/116) |

| INTERMEDIATE | 23.3% (45/193) | 33.3% (15/45) |

| POOR | 8.3% (16/193) | 56% (9/16) |

| VERY POOR | 2.6% (5/193) | 80% (4/5) |

| Karyotype | % MDS Evolution to AML | Odds Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| normal | 6.4% (7/109) | ||

| −7 | 50% (6/12) | 13.67 | 0.00030 |

| +8 | 57% (4/7) | 17.57 | 0.00138 |

| del(11q) | 70% (7/10) | 27.40 | <0.0001 |

| complex | 83% (5/6) | 39.58 | <0.0001 |

| del(7q) | 57% (4/7) | 17.57 | 0.00138 |

| del(12p) | 0% (0/5) | 0.06 | 0.0207 |

| del(17p) | 0% (0/6) | 0.05 | 0.0103 |

| del(6q) | 25% (1/4) | 5.86 | 0.258 |

| +6 | 25% (1/4) | 5.86 | 0.258 |

| +mar | 0% (0/3) | - | - |

| chrb | 0% (0/2) | - | - |

| del(5q) | 0% (0/2) | - | - |

| +21 | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

| i(9q) | 33% (1/3) | - | - |

| inv(9p) | 0% (0/2) | - | - |

| del(9p) | 0% (0/1) | - | - |

| del(3p) | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

| inv(3q) | 0% (0/1) | - | - |

| −19 | 0% (0/1) | - | - |

| del(4q) | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

| −21 | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

| t(2;15) | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

| −Y | 0% (0/1) | - | - |

| +Y | 0% (0/1) | - | - |

| del(13q) | 100% (1/1) | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

da Silva, B.F.; Lovatel, V.L.; Lima, G.F.; Rodrigues, G.M.G.; Borges, M.L.R.d.R.; Tavares, R.d.C.B.; Fonte, A.S.; Horn, P.R.C.B.; Ribeiro-Carvalho, M.d.M.; de Souza, M.H.F.O.; et al. Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Insights on the Disease Biology and Impact on Leukemic Evolution. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122923

da Silva BF, Lovatel VL, Lima GF, Rodrigues GMG, Borges MLRdR, Tavares RdCB, Fonte AS, Horn PRCB, Ribeiro-Carvalho MdM, de Souza MHFO, et al. Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Insights on the Disease Biology and Impact on Leukemic Evolution. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122923

Chicago/Turabian Styleda Silva, Beatriz Ferreira, Viviane Lamim Lovatel, Gabriela Farias Lima, Giulia Miceli Giglio Rodrigues, Maria Luiza Rocha da Rosa Borges, Rita de Cássia Barbosa Tavares, Amanda Suhett Fonte, Patricia Regina Cavalcanti Barbosa Horn, Marilza de Moura Ribeiro-Carvalho, Maria Helena Faria Ornellas de Souza, and et al. 2025. "Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Insights on the Disease Biology and Impact on Leukemic Evolution" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122923

APA Styleda Silva, B. F., Lovatel, V. L., Lima, G. F., Rodrigues, G. M. G., Borges, M. L. R. d. R., Tavares, R. d. C. B., Fonte, A. S., Horn, P. R. C. B., Ribeiro-Carvalho, M. d. M., de Souza, M. H. F. O., Bueno, A. P. S., Costa, E. S., Salles, T. d. J., & Fernandez, T. d. S. (2025). Cytogenetic Abnormalities in Pediatric Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Insights on the Disease Biology and Impact on Leukemic Evolution. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2923. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122923