Atrazine Induces Reproductive Toxicity in an In Vitro Spermatogenesis (IVS) Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

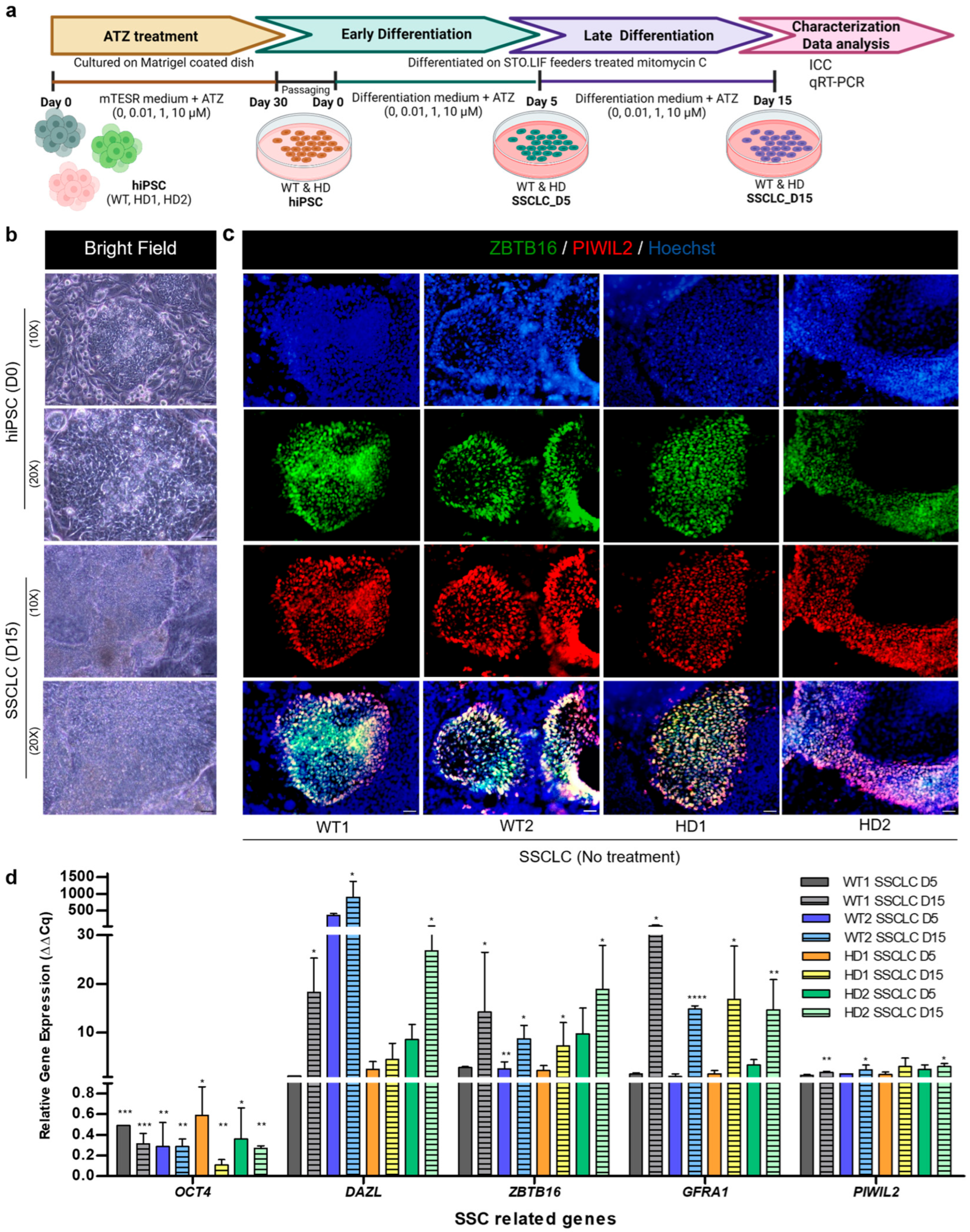

3.1. Directed Differentiation Confirmation of WT and HD-hiPSCs into SSCLCs In Vitro

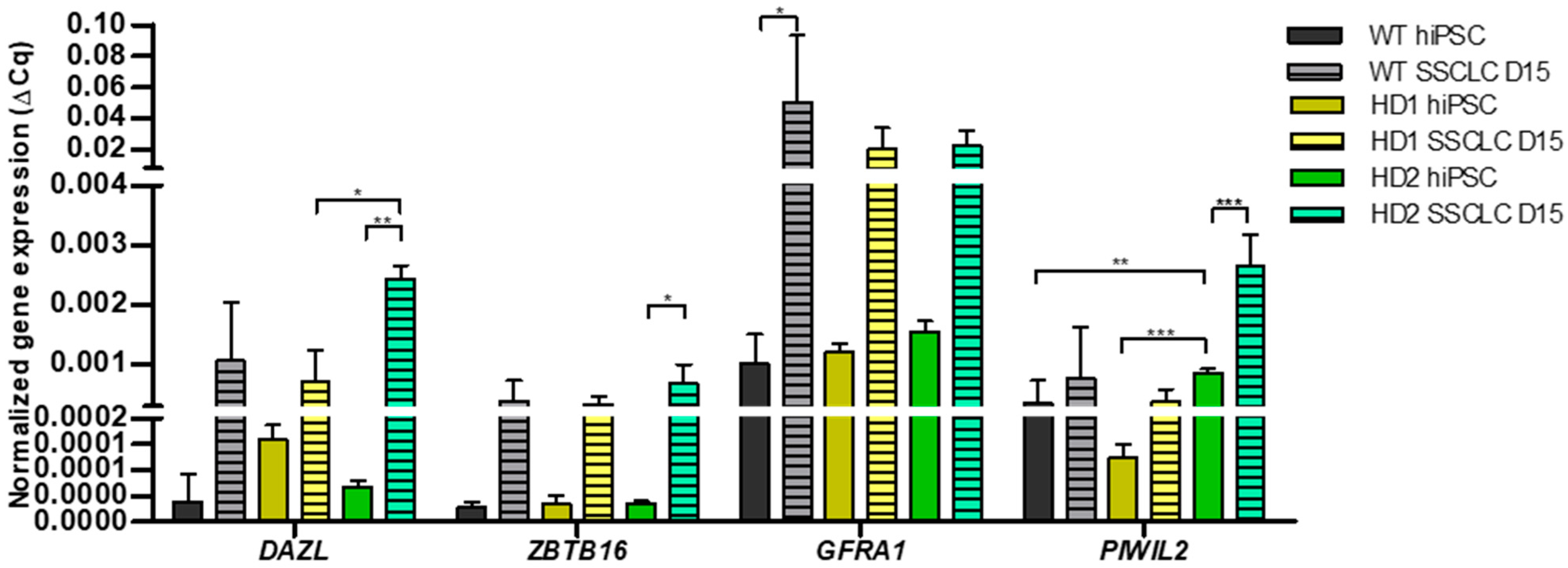

3.2. Comparison of SSC Related Gene Expression Between WT and HD-hiPSCs at Day 15

3.3. Atrazine Exposure Alters Pluripotency in Human iPSCs

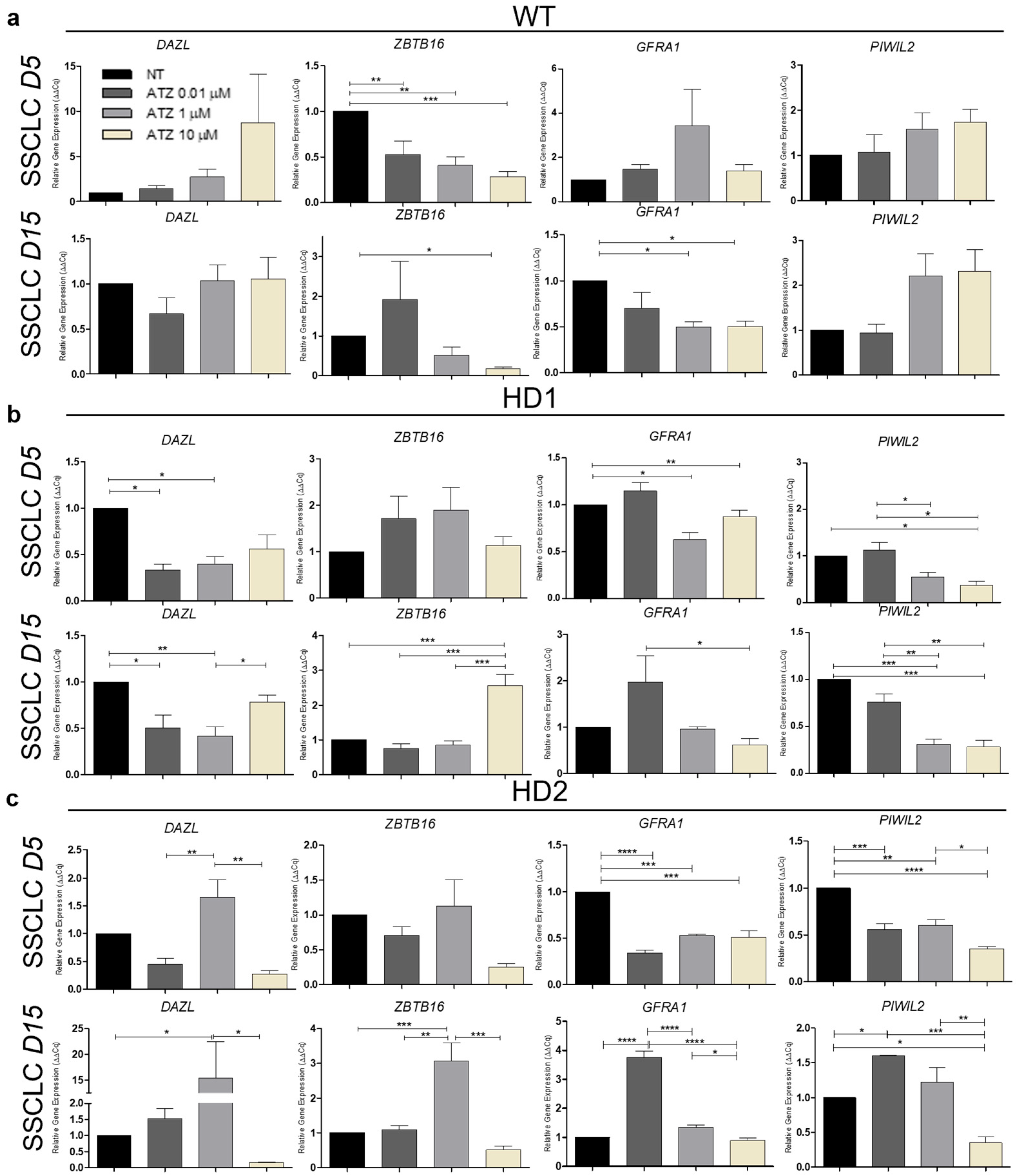

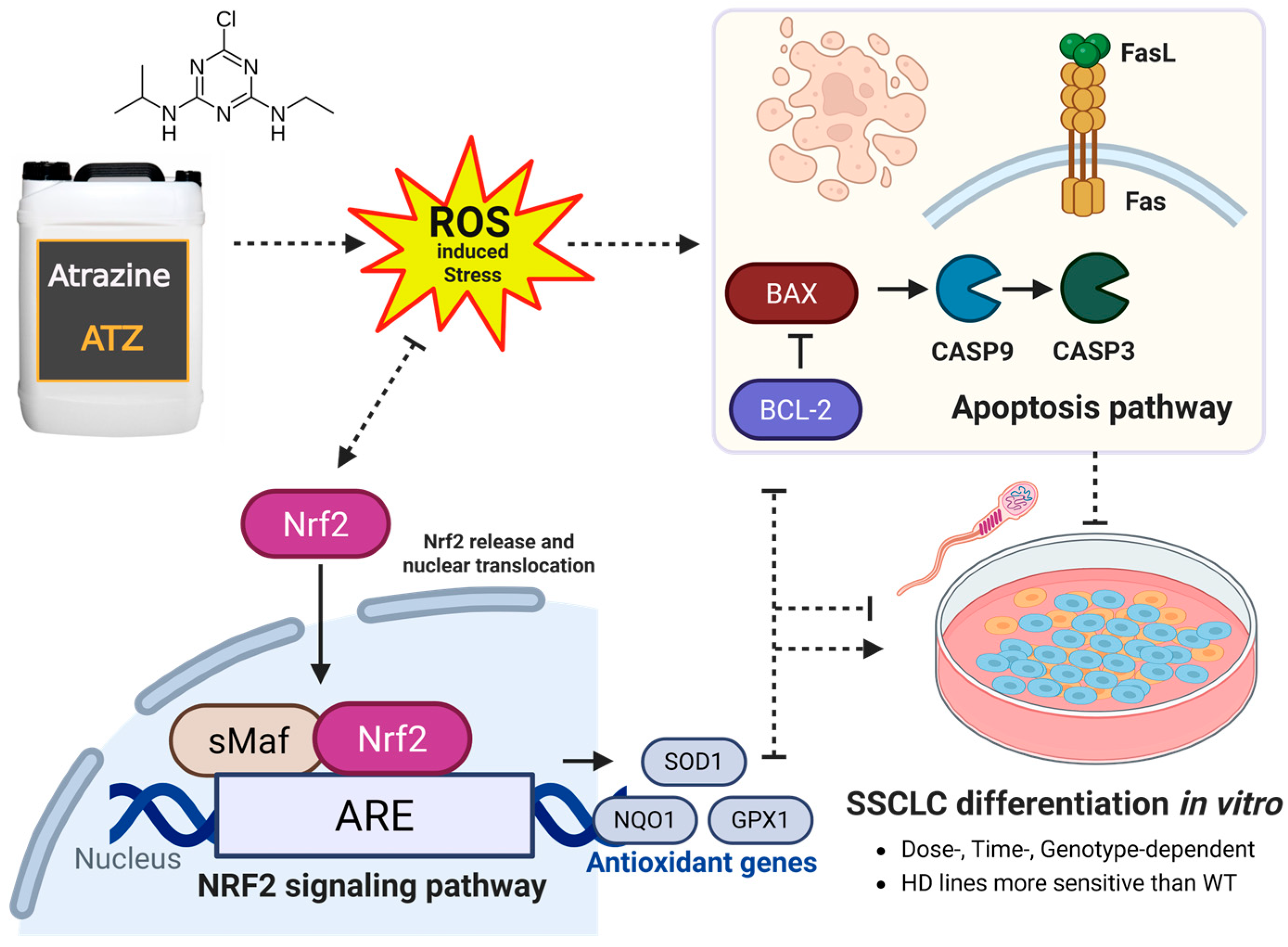

3.4. The Impact of Atrazine on Human Spermatogenesis In Vitro

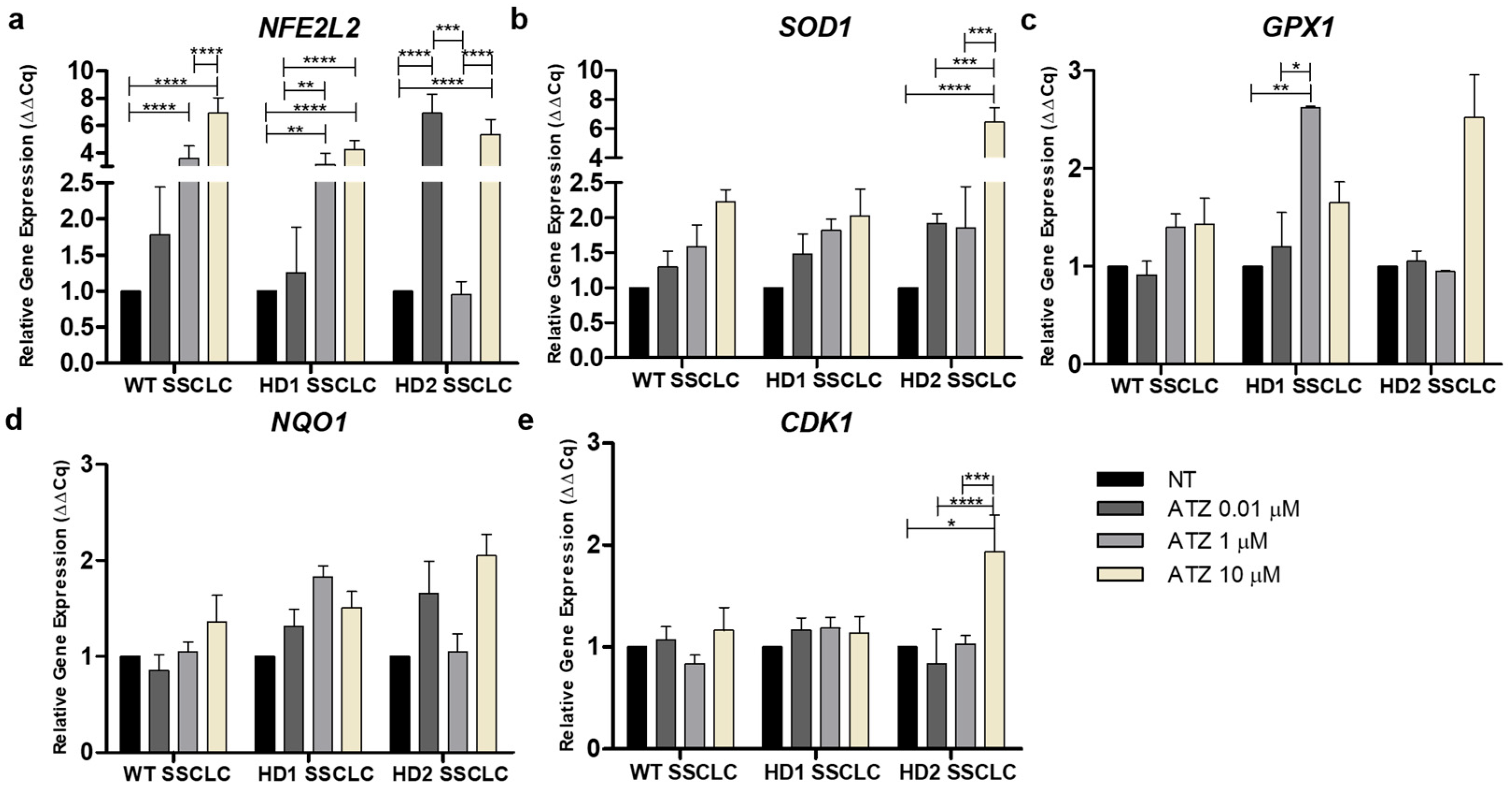

3.5. Atrazine Impacts the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway During In Vitro Spermatogenesis

3.6. Atrazine Alters the Expression of Apoptotic Markers During In Vitro Spermatogenesis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATZ | Atrazine |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| HD | Huntington’s disease |

| hiPSC | Human induced pluripotent stem cell |

| IVS | In vitro spermatogenesis |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 signaling pathway |

| NFE2L2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 gene |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SSC | Spermatogonial stem cell |

| SSCLC | Spermatogonial stem cell-like cell |

| TNR | Trinucleotide repeat |

References

- Mathur, P.P.; D’Cruz, S.C. The effect of environmental contaminants on testicular function. Asian J. Androl. 2011, 13, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinsky, J.L.; Hopenhayn, C.; Golla, V.; Browning, S.; Bush, H.M. Atrazine exposure in public drinking water and preterm birth. Public Health Rep. 2012, 127, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirbisky, S.E.; Weber, G.J.; Sepúlveda, M.S.; Lin, T.L.; Jannasch, A.S.; Freeman, J.L. An embryonic atrazine exposure results in reproductive dysfunction in adult zebrafish and morphological alterations in their offspring. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Meta-analysis and experimental validation identified atrazine as a toxicant in the male reproductive system. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 37482–37497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommery, J.; Mathieu, M.; Mathieu, D.; Lhermitte, M. Atrazine in Plasma and Tissue Following Atrazine-Aminotriazole-Ethylene Glycol-Formaldehyde Poisoning. J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 1993, 31, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Public Health Statement for Atrazine; ATSDR: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. Available online: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/TSP/PHS/PHS.aspx?phsid=336&toxid=59 (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Wang, A.; Hu, X.; Wan, Y.; Mahai, G.; Jiang, Y.; Huo, W.; Zhao, X.; Liang, G.; He, Z.; Xia, W.; et al. A Nationwide Study of the Occurrence and Distribution of Atrazine and Its Degradates in Tap Water and Groundwater in China: Assessment of Human Exposure Potential. Chemosphere 2020, 252, 126533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes-Andrade, D.; Guerra-Carvalho, B.; Carrageta, D.F.; Bernardino, R.L.; Braga, P.C.; Oliveira, P.F.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Alves, M.G. Exposure to Toxicologically Relevant Atrazine Concentrations Impairs the Glycolytic Function of Mouse Sertoli Cells through the Downregulation of Lactate Dehydrogenase. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2024, 486, 116929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, X.N.; Xiang, L.R.; Qin, L.; Lin, J.; Li, J.L. Atrazine triggers hepatic oxidative stress and apoptosis in quails (Coturnix c. coturnix) via blocking Nrf2-mediated defense response. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 137, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, H.S.; Qin, L.; Li, X.N.; Zhang, C.; Xia, J.; Li, J.L. Atrazine triggers mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in quail (Coturnix c. coturnix) cerebrum via activating xenobiotic-sensing nuclear receptors and modulating cytochrome P450 systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 6402–6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotimi, D.E.; Ojo, O.A.; Adeyemi, O.S. Atrazine exposure caused oxidative stress in male rats and inhibited brain-pituitary-testicular functions. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2024, 38, e23579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotimi, D.E.; Ojo, O.A.; Olaolu, T.D.; Adeyemi, O.S. Exploring Nrf2 as a therapeutic target in testicular dysfunction. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 390, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gely-Pernot, A.; Saci, S.; Kernanec, P.-Y.; Hao, C.; Giton, F.; Kervarrec, C.; Tevosian, S.; Mazaud-Guittot, S.; Smagulova, F. Embryonic exposure to the widely-used herbicide atrazine disrupts meiosis and normal follicle formation in female mice. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, S.; Chen, M.; Zhao, F.; Xu, S. Atrazine exposure triggers common carp neutrophil apoptosis via the CYP450s/ROS pathway. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 84, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Yang, J.; Ning, J.; Wang, M.; Song, Q. Atrazine triggers DNA damage response and induces DNA double-strand breaks in MCF-10A cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 14353–14368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, S.H. Semen quality in fertile US men in relation to geographical area and pesticide exposure. Int. J. Androl. 2006, 29, 62–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shu, L.; Chen, L.; Sun, L.; Qian, H.; Liu, W.; Fu, Z. Oxidative stress response and gene expression with atrazine exposure in adult female zebrafish (Danio rerio). Chemosphere 2010, 78, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinfo, N.S.; Hotchkiss, M.G.; Buckalew, A.R.; Zorrilla, L.M.; Cooper, R.L.; Laws, S.C. Understanding the effects of atrazine on steroidogenesis in rat granulosa and H295R adrenal cortical carcinoma cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 31, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarikwu, S.O.; Costa, G.M.J.; de Lima E Martins Lara, N.; Lacerda, S.M.S.N.; de França, L.R. Atrazine impairs testicular function in BalB/c mice by affecting Leydig cells. Toxicology 2021, 455, 152761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Ni, C.; Dong, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, S.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Huang, T.; Lian, Q.; Ge, R.-S. In Utero Exposure to Atrazine Disrupts Rat Fetal Testis Development. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saalfeld, G.Q.; Varela Junior, A.S.; Castro, T.; Pires, D.M.; Pereira, J.R.; Pereira, F.A.; Corcini, C.D.; Colares, E.P. Atrazine Exposure in Gestation and Breastfeeding Affects Calomys laucha Sperm Cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 34953–34963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, L.; Dong, Z.; Li, L.; Guo, Q.; Jia, Q.; Xie, L.; Bo, C.; Liu, Y.; Qu, B.; Li, X.; et al. Gene expression profiles in testis of developing male Xenopus laevis damaged by chronic exposure of atrazine. Chemosphere 2016, 159, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Liu, A.; Zhu, W. Toxic Effects of Atrazine on Reproductive and Immune Systems in Animal Models. Reprod. Syst. Sex. Disord. Curr. Res. 2025, 6, 1000208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, F.E.A.; Varela Junior, A.S.; Corcini, C.D.; Acosta, I.B.; Caldas, S.S.; Primel, E.G.; Zanette, J. The herbicide atrazine affects sperm quality and the expression of antioxidant and spermatogenesis genes in zebrafish testes. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 206–207, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, T.V.; Martin, P.A.; Struger, J.; Sherry, J.; Marvin, C.H.; McMaster, M.E.; Clarence, S.; Tetreault, G. Potential endocrine disruption of sexual development in free ranging male northern leopard frogs (Rana pipiens) and green frogs (Rana clamitans) from areas of intensive row crop agriculture. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 88, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradling, A.; Fuller, M.T.; Braun, R.E.; Yoshida, S. Germline stem cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a002642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.K.; Easley, C.A. Recent Developments in In Vitro Spermatogenesis and Future Directions. Reprod. Med. 2023, 4, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudou, F.; Humbert, S. The Biology of Huntingtin. Neuron 2016, 89, 910–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clever, F.; Cho, I.K.; Yang, J.; Chan, A.W.S. Progressive polyglutamine repeat expansion in peripheral blood cells and sperm of transgenic Huntington’s disease monkeys. J. Huntingtons Dis. 2019, 8, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Sanjana; Singh, N.; Singh, B.; Alam, P. Role of natural products in alleviation of Huntington’s disease: An overview. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 151, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novati, A.; Nguyen, H.P.; Schulze-Hentrich, J. Environmental stimulation in Huntington disease patients and animal models. Neurobiol. Dis. 2022, 171, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.N.; Yu, Y.V.; Gundemir, S.; Jo, C.; Cui, M.; Tieu, K.; Johnson, G.V.W. Impaired mitochondrial dynamics and Nrf2 signaling contribute to compromised responses to oxidative stress in striatal cells expressing full-length mutant huntingtin. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e57932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, N.; Lin, Y.; Santillan, B.A.; Yotnda, P.; Wilson, J.H. Environmental stress induces trinucleotide repeat mutagenesis in human cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3764–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calluori, S.; Stark, R.; Pearson, B.L. Gene–Environment Interactions in Repeat Expansion Diseases: Mechanisms of Environmentally Induced Repeat Instability. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, C.A., IV; Phillips, B.T.; McGuire, M.M.; Barringer, J.M.; Valli, H.; Hermann, B.P.; Simerly, C.R.; Rajkovic, A.; Miki, T.; Orwig, K.E.; et al. Direct differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into haploid spermatogenic cells. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, C.A., IV; Bradner, J.M.; Moser, A.; Rickman, C.A.; McEachin, Z.T.; Merritt, M.M.; Hansen, J.M.; Caudle, W.M. Assessing reproductive toxicity of two environmental toxicants with a novel In Vitro human spermatogenic model. Stem Cell Res. 2015, 14, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.K.; Easley, C.A., IV; Chan, A.W.S. Suppression of trinucleotide repeat expansion in spermatogenic cells in Huntington’s disease. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2022, 39, 2413–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Ye, S.; Liang, D.; Wang, P.; Fu, J.; Ma, Q.; Kong, R.; Shi, L.; Gong, X.; Chen, W.; et al. In Vitro Modeling of Human Germ Cell Development Using Pluripotent Stem Cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2018, 10, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unhavaithaya, Y.; Hao, Y.; Beyret, E.; Yin, H.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; Nakano, T.; Lin, H. MILI, a PIWI-interacting RNA-binding protein, is required for germ line stem cell self-renewal and appears to positively regulate translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 6507–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, M.; Zigo, M.; Kerns, K.; Cho, I.K.; Easley IV, C.A.; Sutovsky, P. Spermatozoan Metabolism as a Non-Traditional Model for the Study of Huntington’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragatsis, I.; Levine, M.S.; Zeitlin, S. Inactivation of Hdh in the brain and testis results in progressive neurodegeneration and sterility in mice. Nat. Genet. 2000, 26, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yefimova, M.G.; Béré, E.; Cantereau-Becq, A.; Harnois, T.; Meunier, A.-C.; Messaddeq, N.; Becq, F.; Trottier, Y.; Bourmeyster, N. Myelinosomes act as natural secretory organelles in Sertoli cells to prevent accumulation of aggregate-prone mutant Huntingtin and CFTR. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 4170–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, J.M.; Murphy, Z.; Selva, D.M.; Hamidizadeh, R.; Pearson, J.; Petersén, A.; Björkqvist, M.; Muir, C.; Mackenzie, I.R.; Hammond, G.L.; et al. Testicular degeneration in Huntington disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 26, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.; Hu, W.; Wen, Y.; Ding, X.; Ma, X.; Yan, W.; Xia, Y. Evaluation of atrazine neurodevelopment toxicity In Vitro—Application of hESC-based neural differentiation model. Reprod. Toxicol. 2021, 103, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Lin, L.; Sánchez, O.F.; Bryan, C.; Freeman, J.L.; Yuan, C. Pre-differentiation exposure to low-dose of atrazine results in persistent phenotypic changes in human neuronal cell lines. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 271, 116379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olejnik, A.M.; Marecik, R.; Białas, W.; Cyplik, P.; Grajek, W. In Vitro Studies on Atrazine Effects on Human Intestinal Cells. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2010, 213, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, T.B.; Anderson, L.L.; Beasley, V.R.; de Solla, S.R.; Iguchi, T.; Ingraham, H.; Kestemont, P.; Kniewald, J.; Kniewald, Z.; Langlois, V.S.; et al. Demasculinization and feminization of male gonads by atrazine: Consistent effects across vertebrate classes. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 127, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, X.; Gong, X.; Yuan, C. Effects of Atrazine on the proliferation and cytotoxicity of murine lymphocytes. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 232, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempfling, A.L.; Lim, S.L.; Adelson, D.L.; Evans, J.; O’Connor, A.E.; Qu, Z.P.; Kliesch, S.; Weidner, W.; O’Bryan, M.K.; Bergmann, M. Expression patterns of HENMT1 and PIWIL1 in human testis: Implications for transposon expression. Reproduction 2017, 154, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, S.; Xie, C.; Tang, T.-S.; Guo, C. Germline deletion of huntingtin causes male infertility and arrested spermiogenesis in mice. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midic, U.; Vincent, K.A.; VandeVoort, C.A.; Latham, K.E. Effects of long-term endocrine disrupting compound exposure on Macaca mulatta embryonic stem cells. Reprod. Toxicol. 2016, 65, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, G. How Sox2 maintains neural stem cell identity. Biochem. J. 2013, 450, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Wang, Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Lalli, M.A.; Kosik, K.S. Nrf2, a regulator of the proteasome, controls self-renewal and pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 2014, 32, 2616–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, K.; Lai, R.; Kundu, R.; Srivastava, S.; Ramalingam, S.; Das, P.; Sethi, G. Oxidative stress induces the acquisition of cancer stem-like phenotype in breast cancer detectable by using a SOX2 regulatory region-2 (SRR2) reporter. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 43620–43634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gopal, K.; Wu, C.; Alshareef, A.; Chow, A.; Wu, F.; Wang, P.; Ye, X.; Bigras, G.; Lai, R. Phosphorylation of SOX2 at Threonine 116 is a potential marker to identify a subset of breast cancer cells with high tumorigenicity and stem-like features. Cancers 2018, 10, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, B.D.O.; Wuebben, E.L.; Rizzino, A. Sox2 Expression is Regulated by a Negative Feedback Loop in Embryonic Stem Cells That Involves AKT Signaling and FoxO1. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Göhner, C.; San Martin, S.; Vattai, A.; Hutter, S.; Parraga, M.; Jeschke, U.; Schleussner, E.; Markert, U.R.; Fitzgerald, J.S. Unique trophoblast stem cell- and pluripotency marker staining patterns depending on gestational age and placenta-associated pregnancy complications. Cell Adh. Migr. 2016, 10, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, J.; Wang, S.; Hong, Y.; Wu, S.; Wei, G. Exploring the toxicological mechanisms of atrazine in prostate cancer by network toxicology and molecular docking. Reprod. Toxicol. 2025, 137, 109001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Tian, Y.; Du, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Li, N.; Liu, W.; Liang, Z.; Zhao, L. Atrazine promotes RM1 prostate cancer cell proliferation by activating STAT3 signaling. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 2166–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarikwu, S.O.; Adesiyan, A.C.; Oyeloja, T.O.; Oyeyemi, M.O.; Farombi, E.O. Changes in sperm characteristics and induction of oxidative stress in the testis and epididymis of experimental rats by a herbicide, atrazine. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 58, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Qin, L.; Dou, D.-C.; Li, X.-N.; Ge, J.; Li, J.-L. Atrazine Induced Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Quail (Coturnix c. coturnix) Kidney via Modulating Nrf2 Signaling Pathway. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarikwu, S.O.; Farombi, E.O. Atrazine induces apoptosis of SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells via the regulation of Bax/Bcl-2 ratio and caspase-3-dependent pathway. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 118, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.; Liu, W.; Xia, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhao, S. Atrazine Promoted Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells Proliferation and Metastasis by Inducing Low Dose Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, e2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Roman, S.D. Antioxidant systems and oxidative stress in the testes. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2008, 1, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J.; Drevet, J.R.; Moazamian, A.; Gharagozloo, P. Male infertility and oxidative stress: A focus on the underlying mechanisms. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, R.J. The global decline in human fertility: The post-transition trap hypothesis. Life 2024, 14, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chaiyakit, M.; Parnpai, R.; Cho, I.K. Atrazine Induces Reproductive Toxicity in an In Vitro Spermatogenesis (IVS) Model. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122917

Chaiyakit M, Parnpai R, Cho IK. Atrazine Induces Reproductive Toxicity in an In Vitro Spermatogenesis (IVS) Model. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122917

Chicago/Turabian StyleChaiyakit, Monsikan, Rangsun Parnpai, and In K. Cho. 2025. "Atrazine Induces Reproductive Toxicity in an In Vitro Spermatogenesis (IVS) Model" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122917

APA StyleChaiyakit, M., Parnpai, R., & Cho, I. K. (2025). Atrazine Induces Reproductive Toxicity in an In Vitro Spermatogenesis (IVS) Model. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122917