Understanding How Mental Health Influences IBD Outcomes: A Review of Potential Culprit Biological Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology of Anxiety and Depression in IBD and Associated Influence on Outcomes

3. Biological Mechanisms Linking Anxiety, Depression and IBD

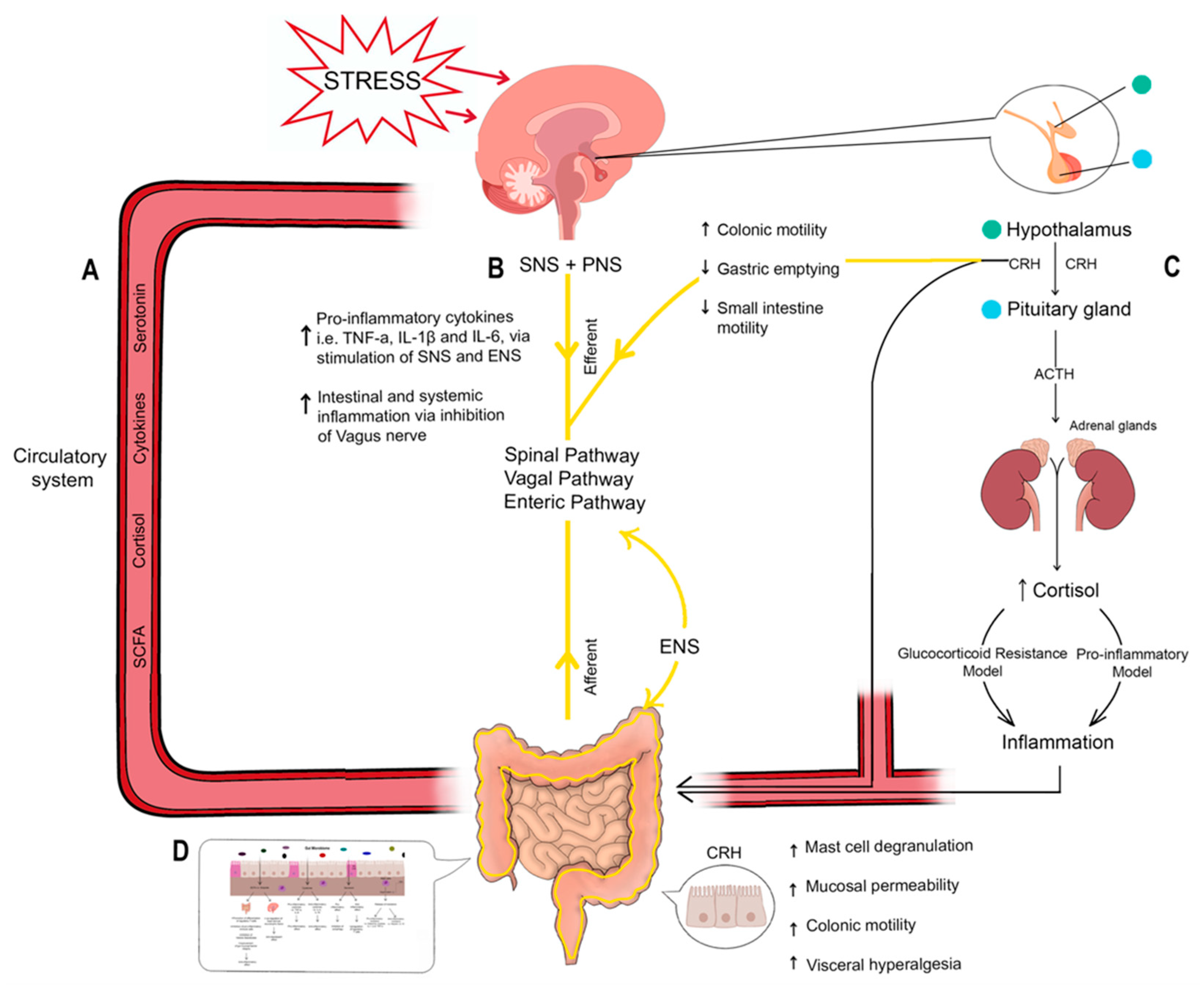

3.1. Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis and Cortisol

3.2. Corticotrophin Releasing Hormone and Mast-Cell Activation

3.3. Autonomic Nervous System

3.4. Immune System and Cytokines

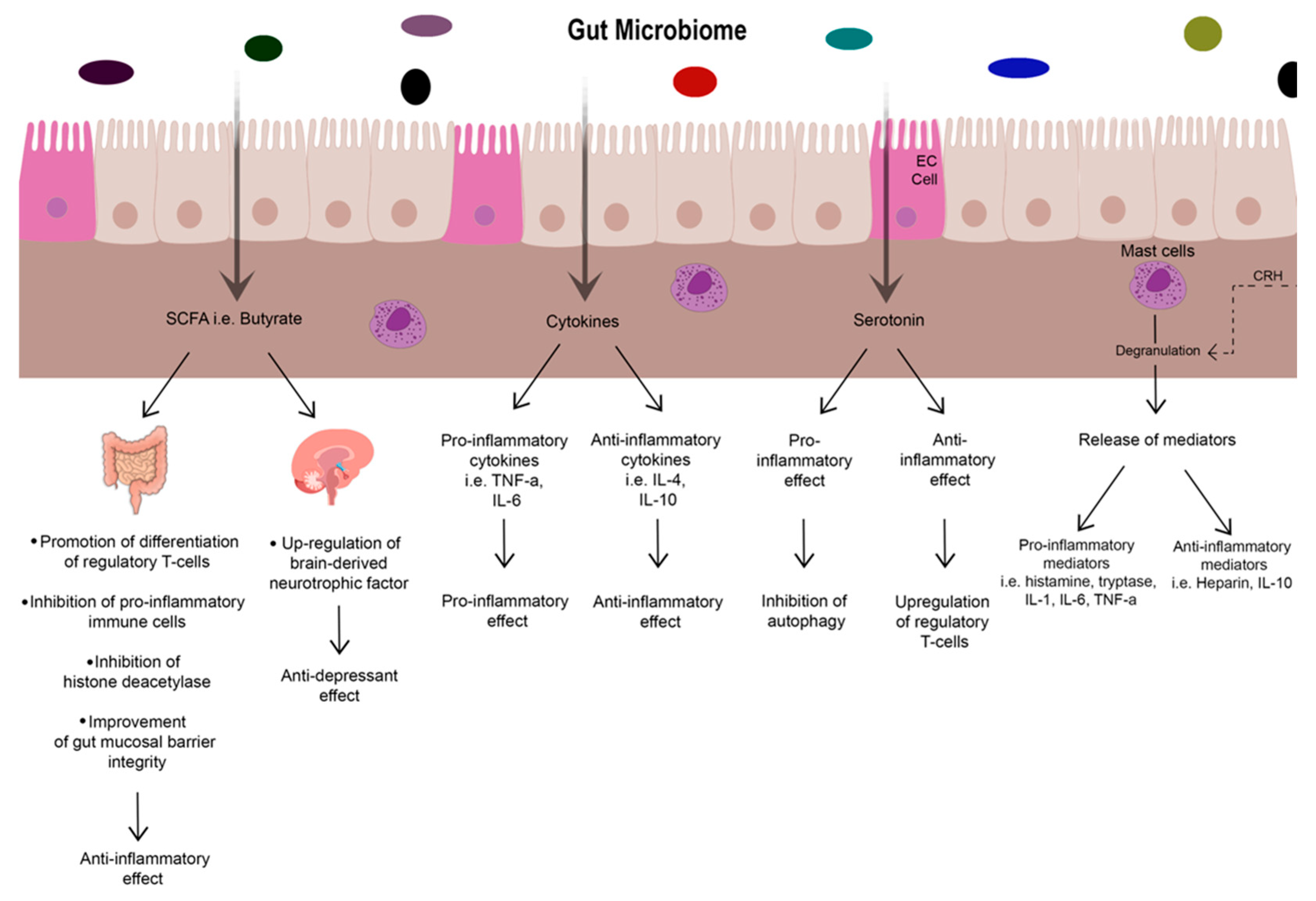

4. The Gut Microbiome

4.1. Neuromodulation, Serotonin and Vascular Barriers

4.2. Microbial Metabolites: Short Chain Fatty Acid (SCFAs)

|

Bacteria

(Genus/Species) |

Prevalence in

Anxiety/Depression |

Prevalence

in IBD | Association with IBD Activity and Anxiety/Depression | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Increased | Increased | Pathogenic strains are associated with increased activity of CD/UC Colibactin-producing E. coli associated with anxiety and depression-like behaviours | Pathogenic Strains, e.g., AIEC associated with worse IBD. |

| Faecalibacterium | Decreased | Decreased | F. prausnitzii—associated with reduced activity of CD/UC and reduction in anxiety-like and depression-like behaviour | Role in SCFA Production. Reduces serotonin degradation leading to increased levels of serotonin in the gut |

| Lactobacillus | Decreased | Variable 1 | Associated with reduced activity of UC-Pre and probiotic administration improved symptoms in UC Certain strains associated with anti-depressant and anxiolytic effects, e.g., L. plantarum 286 | Reduced pro-inflammatory mediators and cortisol. Role in serotonin Synthesis (1) Increased in active CD, but appears protective in UC |

| Clostridioides | Variable | Variable | C. butyricum—associated with reduced activity of UC C. leptum reduction is associated with increased depression severity C. difficile is associated with depression/anxiety-like behaviours. | C. butyricum—associated with SCFA production and increased serotonin |

| Bacteroidetes | Variable 2 | Decreased | B. vulgatus—Associated with reduced activity of both CD/UC + anxiety/depression | (2) Conflicting effects between disease groups. |

| Bifidobacterium | Decreased | Decreased | B. longum—associated with reduced activity of both CD/UC and lower depression scores. | Role in SCFA Production, Tryptophan metabolism |

| Roseburia | Variable | Decreased | Associated with reduced activity of both CD/UC Depletion of Roseburia is associated with MDD | SCFA Production Conflicting research in MDD. May be involved in serotonin expression. |

4.3. Escherichia coli (E. coli)

4.4. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (F. prausnitzii)

4.5. Lactobacillus

4.6. Clostridioides

4.7. Bacteroidetes

4.8. Bifidobacterium

4.9. Roseburia

4.10. Fusobacterium nucleatum (F. nucleatum)

4.11. Diversity

5. Discussion

- High quality longitudinal cohort studies to explore the temporal association of anxiety and depression, and incidence and progression of IBD. Studies that can categorise severity of anxiety and depression would help to identify a dose effect.

- Further data describing different antidepressant classes used in UC and CD with co-morbid anxiety and depression, and their effects on IBD outcomes.

- The role of serotonergic microbiota in the development and progression of IBD and whether this represents a potential therapeutic opportunity [90].

- Further research verifying whether a causal relationship exists between gut microbiome alterations, at a genus or species’ level, and new onset of IBD.

- There is a need for external validation of single-population study findings.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirsner, J.B. Historical Origins of Current IBD Concepts. World J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 7, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracie, D.J.; Guthrie, E.A.; Hamlin, P.J.; Ford, A.C. Bi-Directionality of Brain-Gut Interactions in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 1635–1646.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xu, Z.; Noordam, R.; van Heemst, D.; Li-Gao, R. Depression and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Bidirectional Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. J. Crohns Colitis 2022, 16, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Bernstein, C.N. Environmental Risk Factors for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. UEG J. 2022, 10, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuret, A.E.; Tunnell, N.; Roque, A. Anxiety Disorders and Medical Comorbidity: Treatment Implications. In Anxiety Disorders; Kim, Y.-K., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 1191, pp. 237–261. ISBN 978-981-329-704-3. [Google Scholar]

- Țenea-Cojan, Ș.-T.; Dinescu, V.-C.; Gheorman, V.; Dragne, I.-G.; Gheorman, V.; Forțofoiu, M.-C.; Fortofoiu, M.; Dobrinescu, A.G. Exploring Multidisciplinary Approaches to Comorbid Psychiatric and Medical Disorders: A Scoping Review. Life 2025, 15, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-89042-575-6. [Google Scholar]

- Otte, C.; Gold, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.; Pariante, C.M.; Etkin, A.; Fava, M.; Mohr, D.C.; Schatzberg, A.F. Major Depressive Disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisgaard, T.H.; Allin, K.H.; Elmahdi, R.; Jess, T. The Bidirectional Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Anxiety or Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2023, 83, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovani, D.; Armuzzi, A.; Bonovas, S. Association of Depression with Incident Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, G.E.; Moise, N.; Mohr, D.C. Management of Depression in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remes, O.; Brayne, C.; van der Linde, R.; Lafortune, L. A Systematic Review of Reviews on the Prevalence of Anxiety Disorders in Adult Populations. Brain Behav. 2016, 6, e00497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.R.; Ediger, J.P.; Graff, L.A.; Greenfeld, J.M.; Clara, I.; Lix, L.; Rawsthorne, P.; Miller, N.; Rogala, L.; McPhail, C.M.; et al. The Manitoba IBD Cohort Study: A Population-Based Study of the Prevalence of Lifetime and 12-Month Anxiety and Mood Disorders. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1989–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Y.; Li, H.; Dai, G.; Zhang, X.; Ju, W. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Impact of Depression on Prognosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 1476–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Chen, P.; Liang, C.; Zhang, Y. Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression Associated with Steroid Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1029467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairbrass, K.M.; Lovatt, J.; Barberio, B.; Yuan, Y.; Gracie, D.J.; Ford, A.C. Bidirectional Brain-Gut Axis Effects Influence Mood and Prognosis in IBD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut 2022, 71, 1773–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Tang, Y.; Lei, N.; Luo, Y.; Chen, P.; Liang, C.; Duan, S.; Zhang, Y. Symptoms of Anxiety/Depression Is Associated with More Aggressive Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, G.W.; Gordon, M.; Sinopolou, V.; Radford, S.J.; Darie, A.-M.; Vuyyuru, S.K.; Alrubaiy, L.; Arebi, N.; Blackwell, J.; Butler, T.D.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines on Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Adults: 2025. Gut 2025, 74, s1–s101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lores, T.; Goess, C.; Mikocka-Walus, A.; Collins, K.L.; Burke, A.L.J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Delfabbro, P.; Andrews, J.M. Integrated Psychological Care Is Needed, Welcomed and Effective in Ambulatory Inflammatory Bowel Disease Management: Evaluation of a New Initiative. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2019, 13, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolkis, A.D.; Vallerand, I.A.; Shaheen, A.-A.; Lowerison, M.W.; Swain, M.G.; Barnabe, C.; Patten, S.B.; Kaplan, G.G. Depression Increases the Risk of Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Which May Be Mitigated by the Use of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Depression. Gut 2019, 68, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, J.J.; Beattie, R.M. Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Recent Developments. Arch. Dis. Child. 2024, 109, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppas, S.; Pansieri, C.; Piovani, D.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Tsantes, A.G.; Brunetta, E.; Tsantes, A.E.; Bonovas, S. The Brain-Gut Axis: Psychological Functioning and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abautret-Daly, Á.; Dempsey, E.; Parra-Blanco, A.; Medina, C.; Harkin, A. Gut–Brain Actions Underlying Comorbid Anxiety and Depression Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2018, 30, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.M. Interrogating the Gut-Brain Axis in the Context of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Translational Approach. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, L.; Xie, R.; Wang, B.; Jiang, K.; Cao, H. Stress Triggers Flare of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children and Adults. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariante, C.M.; Miller, A.H. Glucocorticoid Receptors in Major Depression: Relevance to Pathophysiology and Treatment. Biol. Psychiatry 2001, 49, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faravelli, C.; Sauro, C.L.; Godini, L.; Lelli, L.; Benni, L.; Pietrini, F.; Lazzeretti, L.; Talamba, G.A.; Fioravanti, G.; Ricca, V. Childhood Stressful Events, HPA Axis and Anxiety Disorders. World J. Psychiatry 2012, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gądek-Michalska, A.; Tadeusz, J.; Rachwalska, P.; Bugajski, J. Cytokines, Prostaglandins and Nitric Oxide in the Regulation of Stress-Response Systems. Pharmacol. Rep. 2013, 65, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, P.W.; Machado-Vieira, R.; Pavlatou, M.G. Clinical and Biochemical Manifestations of Depression: Relation to the Neurobiology of Stress. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015, 581976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amasi-Hartoonian, N.; Sforzini, L.; Cattaneo, A.; Pariante, C.M. Cause or Consequence? Understanding the Role of Cortisol in the Increased Inflammation Observed in Depression. Curr. Opin. Endocr. Metab. Res. 2022, 24, 100356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattsand, R.; Linden, M. Cytokine Modulation by Glucocorticoids: Mechanisms and Actions in Cellular Studies. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1996, 10, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberts, S. The Glucocorticoid Insensitivity Syndrome. Horm. Res. 1996, 45, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariante, C.M.; Lightman, S.L. The HPA Axis in Major Depression: Classical Theories and New Developments. Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, K.M.; Blank, N.; Alvarez, Y.; Thum, K.; Lundgren, P.; Litichevskiy, L.; Sleeman, M.; Bahnsen, K.; Kim, J.; Kardo, S.; et al. The Enteric Nervous System Relays Psychological Stress to Intestinal Inflammation. Cell 2023, 186, 2823–2838.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stengel, A.; Taché, Y. Corticotropin-Releasing Factor Signaling and Visceral Response to Stress. Exp. Biol. Med. 2010, 235, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Fleur, S.E.; Wick, E.C.; Idumalla, P.S.; Grady, E.F.; Bhargava, A. Role of Peripheral Corticotropin-Releasing Factor and Urocortin II in Intestinal Inflammation and Motility in Terminal Ileum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 7647–7652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahito, Y.; Sano, H.; Kawata, M.; Yuri, K.; Mukai, S.; Yamamura, Y.; Kato, H.; Chrousos, G.P.; Wilder, R.L.; Kondo, M. Local Secretion of Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone by Enterochromaffin Cells in Human Colon. Gastroenterology 1994, 106, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tache, Y.; Larauche, M.; Yuan, P.-Q.; Million, M. Brain and Gut CRF Signaling: Biological Actions and Role in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanuytsel, T.; van Wanrooy, S.; Vanheel, H.; Vanormelingen, C.; Verschueren, S.; Houben, E.; Rasoel, S.S.; Tόth, J.; Holvoet, L.; Farré, R.; et al. Psychological Stress and Corticotropin-Releasing Hormone Increase Intestinal Permeability in Humans by a Mast Cell-Dependent Mechanism. Gut 2014, 63, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tache, Y.; Perdue, M. Role of Peripheral CRF Signalling Pathways in Stress-related Alterations of Gut Motility and Mucosal Function. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2004, 16, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, T.; Dalziel, J.; Coad, J.; Roy, N.; Butts, C.; Gopal, P. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis and Resilience to Developing Anxiety or Depression under Stress. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, D.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vanuytsel, T.; Verbeke, K. Psychosocial Stress-Induced Intestinal Permeability in Healthy Humans: What Is the Evidence? Neurobiol. Stress 2023, 27, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karban, A.; Eliakim, R. Effect of Smoking on Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Is It Disease or Organ Specific? World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 2150–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, E.L.; Rivier, J.E.; Moeser, A.J. CRF Induces Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Injury via the Release of Mast Cell Proteases and TNF-α. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallon, C.; Persborn, M.; Jönsson, M.; Wang, A.; Phan, V.; Lampinen, M.; Vicario, M.; Santos, J.; Sherman, P.M.; Carlson, M.; et al. Eosinophils Express Muscarinic Receptors and Corticotropin-Releasing Factor to Disrupt the Mucosal Barrier in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1597–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.-H. Key Role of Mast Cells and Their Major Secretory Products in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorak, A.M.; Monahan, R.A.; Osage, J.E.; Dickersin, G.R. Crohn’s Disease: Transmission Electron Microscopic Studies: II. Immunologic Inflammatory Response. Alterations of Mast Cells, Basophils, Eosinophils, and the Microvasculature. Hum. Pathol. 1980, 11, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, G.; Green, F.; Fox, H.; Mani, V.; Turnberg, L. Mast Cells and Immunoglobulin E in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 1975, 16, 861–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljameeli, A.M.; Alsuwayt, B.; Bharati, D.; Gohri, V.; Mohite, P.; Singh, S.; Chidrawar, V. Chloride Channels and Mast Cell Function: Pioneering New Frontiers in IBD Therapy. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2025, 480, 3951–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chichlowski, M.; Westwood, G.S.; Abraham, S.N.; Hale, L.P. Role of Mast Cells in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Inflammation-Associated Colorectal Neoplasia in IL-10-Deficient Mice. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, C.-L.; He, J.; Liu, S.-D. Causal Associations Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Anxiety: A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5872–5881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions Between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Gershon, M.D. The Bowel and beyond: The Enteric Nervous System in Neurological Disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.; Campisi, J.; Sharkey, C.; Kennedy, S.; Nickerson, M.; Greenwood, B.; Fleshner, M. Catecholamines Mediate Stress-Induced Increases in Peripheral and Central Inflammatory Cytokines. Neuroscience 2005, 135, 1295–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, J.B. Enteric Nervous System. In Encyclopedia of Neuroscience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 1122–1125. ISBN 3-540-29678-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Mawe, G.M. The Enteric Nervous System. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1487–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, R.K.; Hirano, I. The Enteric Nervous System. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershon, M.D. The Enteric Nervous System. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1981, 4, 227–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, E.; Kim, Y.-K. Stress, the Autonomic Nervous System, and the Immune-Kynurenine Pathway in the Etiology of Depression. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiet, T.; Rutgeerts, P.; Ferrante, M.; Van Assche, G.; Vermeire, S. Targeting TNF-α for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2014, 14, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targan, S.R.; Hanauer, S.B.; Van Deventer, S.J.H.; Mayer, L.; Present, D.H.; Braakman, T.; DeWoody, K.L.; Schaible, T.F.; Rutgeerts, P.J. A Short-Term Study of Chimeric Monoclonal Antibody cA2 to Tumor Necrosis Factor α for Crohn’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurath, M.F. Cytokines in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, H.; Gould, R.L.; Abrol, E.; Howard, R. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Peripheral Inflammatory Cytokines and Generalised Anxiety Disorder. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowlati, Y.; Herrmann, N.; Swardfager, W.; Liu, H.; Sham, L.; Reim, E.K.; Lanctôt, K.L. A Meta-Analysis of Cytokines in Major Depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, M.M.; Ferreira, T.B.; Pacheco, P.A.; Barros, P.O.; Almeida, C.R.; Araújo-Lima, C.F.; Silva-Filho, R.G.; Hygino, J.; Andrade, R.M.; Linhares, U.C. Enhanced Th17 Phenotype in Individuals with Generalized Anxiety Disorder. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010, 229, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, R.; Garner, M.; Holmes, C.; Osmond, C.; Teeling, J.; Lau, L.; Baldwin, D.S. Peripheral Inflammatory Cytokines and Immune Balance in Generalised Anxiety Disorder: Case-Controlled Study. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017, 62, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halfvarson, J.; Brislawn, C.J.; Lamendella, R.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Walters, W.A.; Bramer, L.M.; D’Amato, M.; Bonfiglio, F.; McDonald, D.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Dynamics of the Human Gut Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, H.; Pigneur, B.; Watterlot, L.; Lakhdari, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Gratadoux, J.-J.; Blugeon, S.; Bridonneau, C.; Furet, J.-P.; Corthier, G.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Is an Anti-Inflammatory Commensal Bacterium Identified by Gut Microbiota Analysis of Crohn Disease Patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 16731–16736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willing, B.; Halfvarson, J.; Dicksved, J.; Rosenquist, M.; Järnerot, G.; Engstrand, L.; Tysk, C.; Jansson, J.K. Twin Studies Reveal Specific Imbalances in the Mucosa-Associated Microbiota of Patients with Ileal Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willing, B.P.; Dicksved, J.; Halfvarson, J.; Andersson, A.F.; Lucio, M.; Zheng, Z.; Järnerot, G.; Tysk, C.; Jansson, J.K.; Engstrand, L. A Pyrosequencing Study in Twins Shows That Gastrointestinal Microbial Profiles Vary with Inflammatory Bowel Disease Phenotypes. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 1844–1854.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karen, C.; Shyu, D.J.H.; Rajan, K.E. Lactobacillus paracasei Supplementation Prevents Early Life Stress-Induced Anxiety and Depressive-Like Behavior in Maternal Separation Model-Possible Involvement of Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Differential Regulation of MicroRNA124a/132 and Glutamate Receptors. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 719933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenbergen, L.; Sellaro, R.; van Hemert, S.; Bosch, J.A.; Colzato, L.S. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Test the Effect of Multispecies Probiotics on Cognitive Reactivity to Sad Mood. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qi, N.; Zeng, Y.; Bao, M.; Chen, Y.; Liao, J.; Wei, L.; Cao, D.; Huang, S.; Luo, Q.; et al. The Endogenous Alterations of the Gut Microbiota and Feces Metabolites Alleviate Oxidative Damage in the Brain of LanCL1 Knockout Mice. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 557342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, J.; Tong, Y.; Wang, P. Crocetin Ameliorates Chronic Restraint Stress-Induced Depression-like Behaviors in Mice by Regulating MEK/ERK Pathways and Gut Microbiota. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 268, 113608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.A. Dysbiosis. In The Microbiota in Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Ling, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Mao, H.; Ma, Z.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, W.; Tan, Z.; Shi, J.; et al. Altered Fecal Microbiota Composition in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 48, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Littman, D.R. The Microbiota in Adaptive Immune Homeostasis and Disease. Nature 2016, 535, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmela, C.; Chevarin, C.; Xu, Z.; Torres, J.; Sevrin, G.; Hirten, R.; Barnich, N.; Ng, S.C.; Colombel, J.-F. Adherent-Invasive Escherichia coli in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gut 2018, 67, 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.A.; Barnich, N.; Sauvanet, P.; Darcha, C.; Gelot, A.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A. Crohn’s Disease-Associated Escherichia coli LF82 Aggravates Colitis in Injured Mouse Colon via Signaling by Flagellin. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2008, 14, 1051–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.; Wang, H.; Grondin, J.; Banskota, S.; Marshall, J.K.; Khan, I.I.; Chauhan, U.; Cote, F.; Kwon, Y.H.; Philpott, D.; et al. Disruption of Autophagy by Increased 5-HT Alters Gut Microbiota and Enhances Susceptibility to Experimental Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabi6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, W.; Guan, J.; Cui, J.; Shi, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y. Latest Updates on the Serotonergic System in Depression and Anxiety. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1124112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M.; Gray, J.A.; Roth, B.L. The Expanded Biology of Serotonin. Annu. Rev. Med. 2009, 60, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Gao, L.; Chen, P.; Feng, D.; Jiang, Y.; Chang, Y.; Jin, J.; Chu, F.-F.; Gao, Q. Serotonin-Exacerbated DSS-Induced Colitis Is Associated with Increase in MMP-3 and MMP-9 Expression in the Mouse Colon. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 5359768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.H.; Wang, H.; Denou, E.; Ghia, J.-E.; Rossi, L.; Fontes, M.E.; Bernier, S.P.; Shajib, M.S.; Banskota, S.; Collins, S.M.; et al. Modulation of Gut Microbiota Composition by Serotonin Signaling Influences Intestinal Immune Response and Susceptibility to Colitis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 7, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghia, J.; Li, N.; Wang, H.; Collins, M.; Deng, Y.; El–Sharkawy, R.T.; Côté, F.; Mallet, J.; Khan, W.I. Serotonin Has a Key Role in Pathogenesis of Experimental Colitis. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, J.A.; Khan, W.I. Emerging Roles of Gut Serotonin in Regulation of Immune Response, Microbiota Composition and Intestinal Inflammation. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2024, 7, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuboi, K.; Nishitani, M.; Takakura, A.; Imai, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Kawashima, H. Autophagy Protects against Colitis by the Maintenance of Normal Gut Microflora and Secretion of Mucus*. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20511–20526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, T.; Fujita, N.; Jang, M.H.; Uematsu, S.; Yang, B.-G.; Satoh, T.; Omori, H.; Noda, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Komatsu, M.; et al. Loss of the Autophagy Protein Atg16L1 Enhances Endotoxin-Induced IL-1β Production. Nature 2008, 456, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, S.; Grondin, J.; Banskota, S.; Khan, W.I. Autophagy: Roles in Intestinal Mucosal Homeostasis and Inflammation. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanidad, K.Z.; Rager, S.L.; Carrow, H.C.; Ananthanarayanan, A.; Callaghan, R.; Hart, L.R.; Li, T.; Ravisankar, P.; Brown, J.A.; Amir, M.; et al. Gut Bacteria–Derived Serotonin Promotes Immune Tolerance in Early Life. Sci. Immunol. 2024, 9, eadj4775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braniste, V.; Al-Asmakh, M.; Kowal, C.; Anuar, F.; Abbaspour, A.; Tóth, M.; Korecka, A.; Bakocevic, N.; Ng, L.G.; Kundu, P.; et al. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 263ra158, Erratum in: Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 266er7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scalise, A.A.; Kakogiannos, N.; Zanardi, F.; Iannelli, F.; Giannotta, M. The Blood–Brain and Gut–Vascular Barriers: From the Perspective of Claudins. Tissue Barriers 2021, 9, 1926190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tommaso, N.D.; Santopaolo, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Ponziani, F.R. The Gut–Vascular Barrier as a New Protagonist in Intestinal and Extraintestinal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitali, R.; Stronati, L.; Negroni, A.; Di Nardo, G.; Pierdomenico, M.; Del Giudice, E.; Rossi, P.; Cucchiara, S. Fecal HMGB1 Is a Novel Marker of Intestinal Mucosal Inflammation in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 2029–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.; Kim, S.J.; Howe, C.; Lee, S.; Her, J.Y.; Patel, M.; Kim, G.; Lee, J.; Im, E.; Rhee, S.H. Chronic Intestinal Inflammation Suppresses Brain Activity by Inducing Neuroinflammation in Mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2022, 192, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheline, Y.I.; Sanghavi, M.; Mintun, M.A.; Gado, M.H. Depression duration but not age predicts hippocampal volume loss in medically healthy women with recurrent major depression. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 5034–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Videbech, P.; Ravnkilde, B. Hippocampal Volume and Depression: A Meta-Analysis of MRI Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 1957–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strandwitz, P. Neurotransmitter Modulation by the Gut Microbiota. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopman, N.; Katsavelis, D.; Hove, A.S.T.; Brul, S.; de Jonge, W.J.; Seppen, J. The Multifaceted Role of Serotonin in Intestinal Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Delgado, S.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Trejo-Vazquez, F.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Interplay Between Serotonin, Immune Response, and Intestinal Dysbiosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigstad, C.S.; Salmonson, C.E.; Rainey, J.F.; Szurszewski, J.H.; Linden, D.R.; Sonnenburg, J.L.; Farrugia, G.; Kashyap, P.C. Gut Microbes Promote Colonic Serotonin Production through an Effect of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Enterochromaffin Cells. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 1395–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Sung, Y.-B.; Chung, S.-Y.; Kwon, M.-S. Possible Additional Antidepressant-like Mechanism of Sodium Butyrate: Targeting the Hippocampus. Neuropharmacology 2014, 81, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouna, S.; Gonçalvès, D.; Barnich, N.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A.; Hofman, P.; Vouret-Craviari, V. Crohn Disease-Associated Escherichia coli Promote Gastrointestinal Inflammatory Disorders by Activation of HIF-Dependent Responses. Gut Microbes 2011, 2, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.-M.; Lee, K.-E.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Immobilization Stress-Induced Escherichia coli Causes Anxiety by Inducing NF-κB Activation through Gut Microbiota Disturbance. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Chang, E.B. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and the Microbiome: Searching the Crime Scene for Clues. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leylabadlo, H.E.; Ghotaslou, R.; Feizabadi, M.M.; Farajnia, S.; Moaddab, S.Y.; Ganbarov, K.; Khodadadi, E.; Tanomand, A.; Sheykhsaran, E.; Yousefi, B.; et al. The Critical Role of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in Human Health: An Overview. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 149, 104344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Bai, J.; Wu, D.; Yu, S.; Qiang, X.; Bai, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, Z. Association Between Fecal Microbiota and Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Severity and Early Treatment Response. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 259, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondepierre, F.; Meynier, M.; Gagniere, J.; Deneuvy, V.; Deneuvy, A.; Roche, G.; Baudu, E.; Pereira, B.; Bonnet, R.; Barnich, N.; et al. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence of the Association of Colibactin-Producing Escherichia coli with Anxiety and Depression in Colon Cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 2817–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Siles, M.; Duncan, S.H.; Garcia-Gil, L.J.; Martinez-Medina, M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: From Microbiology to Diagnostics and Prognostics. ISME J. 2017, 11, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miquel, S.; Martín, R.; Rossi, O.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.; Chatel, J.; Sokol, H.; Thomas, M.; Wells, J.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Human Intestinal Health. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, M.S.; Rasoulpour, R.J.; Yin, L.; Hubbard, A.K.; Rosenberg, D.W.; Giardina, C. The Luminal Short-Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate Modulates NF-κB Activity in a Human Colonic Epithelial Cell Line. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.; Willing, B.; Lucio, M.; Fekete, A.; Dicksved, J.; Halfvarson, J.; Tysk, C.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P. Metabolomics Reveals Metabolic Biomarkers of Crohn’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol, H.; Seksik, P.; Furet, J.P.; Firmesse, O.; Nion-Larmurier, I.; Beaugerie, L.; Cosnes, J.; Corthier, G.; Marteau, P.; Doré, J. Low Counts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in Colitis Microbiota. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2009, 15, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klampfer, L.; Huang, J.; Sasazuki, T.; Shirasawa, S.; Augenlicht, L. Inhibition of Interferon Gamma Signaling by the Short Chain Fatty Acid Butyrate. Mol. Cancer Res. 2003, 1, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De la Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuthpongtorn, C.; Chan, A.A.; Ma, W.; Wang, F.; Nguyen, L.H.; Wang, D.D.; Okereke, O.I.; Huttenhower, C.; Chan, A.T.; Mehta, R.S. F. prausnitzii Potentially Modulates the Association Between Citrus Intake and Depression. Microbiome 2024, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Miquel, S.; Chain, F.; Natividad, J.M.; Jury, J.; Lu, J.; Sokol, H.; Theodorou, V.; Bercik, P.; Verdu, E.F.; et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii Prevents Physiological Damages in a Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation Murine Model. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Wang, W.; Guo, R.; Liu, H. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (ATCC 27766) Has Preventive and Therapeutic Effects on Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Depression-like and Anxiety-like Behavior in Rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 104, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-S.; Shin, G.-E.; Cheong, Y.; Shin, J.-H.; Shin, D.-M.; Chun, W.Y. Experiencing Social Exclusion Changes Gut Microbiota Composition. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganji-Arjenaki, M.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. Probiotics Are a Good Choice in Remission of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Meta Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Cell Physiol. 2018, 233, 2091–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeney, D.D.; Gareau, M.G.; Marco, M.L. Intestinal Lactobacillus in Health and Disease, a Driver or Just along for the Ride? Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2018, 49, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Zhou, R.; Wang, X.; Song, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, G.; Xia, B. Increased Proportions of Bifidobacterium and the Lactobacillus Group and Loss of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J.D.; Chen, E.Z.; Baldassano, R.N.; Otley, A.R.; Griffiths, A.M.; Lee, D.; Bittinger, K.; Bailey, A.; Friedman, E.S.; Hoffmann, C.; et al. Inflammation, Antibiotics, and Diet as Environmental Stressors of the Gut Microbiome in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-M.; Wu, C.-C.; Huang, C.-L.; Chang, M.-Y.; Cheng, S.-H.; Lin, C.-T.; Tsai, Y.-C. Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 Promotes Intestinal Motility, Mucin Production, and Serotonin Signaling in Mice. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2022, 14, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, B.; Duan, Z.; Xia, Z.; Ding, Y.; Chen, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Yang, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Active Ulcerative Colitis: Crosstalk of Gut Microbiota, Metabolomics and Proteomics. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1987779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Santos, T.; Silva, K.S.O.; Libarino-Santos, M.; Cata-Preta, E.G.; Reis, H.S.; Tamura, E.K.; de Oliveira-Lima, A.J.; Berro, L.F.; Uetanabaro, A.P.T.; Marinho, E.A.V. Effects of Chronic Treatment with New Strains of Lactobacillus plantarum on Cognitive, Anxiety- and Depressive-like Behaviors in Male Mice. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Peng, K.; Xiao, S.; Long, Y.; Yu, Q. The Role of Lactobacillus in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Actualities to Prospects. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, J.; Palagani, V.; Bozko, P. The Intestinal Microbiota Dysbiosis and Clostridium Difficile Infection: Is There a Relationship with Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitzan, O.; Elias, M.; Chazan, B.; Raz, R.; Saliba, W. Clostridium Difficile and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Role in Pathogenesis and Implications in Treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 7577–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, M.-K.; Ma, X.; Shin, J.-W.; Shin, Y.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Lactococcus Lactis and Bifidobacterium longum Attenuate Clostridioides difficile- or Clostridium symbiosum-Induced Colitis and Depression/Anxiety-like Behavior in Male Mice. Microbes Infect. 2025, 27, 105560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, N.; Matsuzaki, H.; Shimada, S. Characterization of Early Life Stress-Affected Gut Microbiota. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M.T.; Dowd, S.E.; Galley, J.D.; Hufnagle, A.R.; Allen, R.G.; Lyte, M. Exposure to a Social Stressor Alters the Structure of the Intestinal Microbiota: Implications for Stressor-Induced Immunomodulation. Brain Behav. Immun. 2011, 25, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Wang, F.; Hu, X.; Yang, C.; Xu, H.; Yao, Y.; Liu, J. Clostridium butyricum Attenuates Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress-Induced Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice via the Gut-Brain Axis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8415–8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Cope, J.L.; Nagy-Szakal, D.; Dowd, S.; Versalovic, J.; Hollister, E.B.; Kellermayer, R. Composition and Function of the Pediatric Colonic Mucosal Microbiome in Untreated Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.L.; Li, Q.; Minhajuddin, A.; Czysz, A.H.; Coughlin, L.A.; Hussain, S.K.; Koh, A.Y.; Trivedi, M.H. Reduced Anti-Inflammatory Gut Microbiota Are Associated with Depression and Anhedonia. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhi, F. Lower Level of Bacteroides in the Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 5828959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fan, Q.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Z.; Cai, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, J.; He, D.; Wang, G.; et al. Bacteroides Species Differentially Modulate Depression-like Behavior via Gut-Brain Metabolic Signaling. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 102, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Tan, X.; Wen, L.; Zhou, X.; Xie, P.; Olasunkanmi, O.I.; et al. Changes of Gut Microbiota Reflect the Severity of Major Depressive Disorder: A Cross Sectional Study. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Deng, M.; Shen, Z.; Nie, K.; Luo, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, K.; Chen, X.; et al. Bacteroides Vulgatus Alleviates Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis and Depression-like Behaviour by Facilitating Gut-Brain Axis Balance. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1287271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Wang, G.; Zheng, X.; Hao, H. Gut Microbial Metabolites of Aromatic Amino Acids as Signals in Host–Microbe Interplay. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 818–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xie, S.; Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, J.; Kishawy, A.T.Y.; Gu, L.; et al. Effects of 4-Hydroxyphenylacetic Acid, a Phenolic Acid Compound from Yucca schidigera Extract, on Immune Function and Intestinal Health in Meat Pigeons. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, X. Bifidobacterium longum: Protection against Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 8030297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Shi, L.; Ou, M.; Du, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, H. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Metabolomic Pathways in Modulating the Efficacy of SSRIs for Major Depressive Disorder. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Hua, Z.; Zou, X. Bifidobacterium longum Affects the Methylation Level of Forkhead Box P3 Promoter in 2, 4, 6-Trinitrobenzenesulphonic Acid Induced Colitis in Rats. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 110, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Peng, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Feng, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, T.; Yao, G.; Zhang, H.; He, Q. Both Viable Bifidobacterium longum Subsp. Infantis B8762 and Heat-Killed Cells Alleviate the Intestinal Inflammation of DSS-Induced IBD Rats. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0350923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, L.; Qian, W.; Zheng, F.; Hou, X. Bifidobacterium longum and VSL#3® Amelioration of TNBS-Induced Colitis Associated with Reduced HMGB1 and Epithelial Barrier Impairment. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019, 92, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Hall, G.B.; Ghajar, K.; Nardelli, A.; Bolino, C.; Lau, J.T.; Martin, F.-P.; Cominetti, O.; Welsh, C.; Rieder, A.; et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 Reduces Depression Scores and Alters Brain Activity: A Pilot Study in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 448–459.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, W.; Diao, J.; Sun, L.; Meng, M. Gut Microbiota Variations in Depression and Anxiety: A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2025, 25, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Pan, T.; Li, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Lu, W. Bifidobacterium longum Mediated Tryptophan Metabolism to Improve Atopic Dermatitis via the Gut-Skin Axis. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2044723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, F.-T.; Xia, K.; Gao, R.-Y.; Jiao, Y.-R.; Fang, M.; Chen, C.-Q. Impact of Terminal Ileal Microbiota Dysbiosis and Tryptophan Metabolism Alterations on Mental Disorders in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaus, S.; Schulte, B.; Al-Massad, N.; Thieme, F.; Schulte, D.M.; Bethge, J.; Rehman, A.; Tran, F.; Aden, K.; Häsler, R.; et al. Increased Tryptophan Metabolism Is Associated with Activity of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 1504–1516.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Du, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Lai, W.; Li, S.; Ye, Z.; Fu, W.; Li, S.; Li, X.-G.; et al. Association Between Metabolites in Tryptophan-Kynurenine Pathway and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarangelo, F.M.; Schwarcz, R. Restraint Stress During Pregnancy Rapidly Raises Kynurenic Acid Levels in Mouse Placenta and Fetal Brain. Dev. Neurosci. 2016, 38, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, K.; Ma, K.; Luo, W.; Shen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, M.; Tong, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X. Roseburia Intestinalis: A Beneficial Gut Organism from the Discoveries in Genus and Species. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 757718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Song, K.; Shen, Z.; Quan, Y.; Tan, B.; Luo, W.; Wu, S.; Tang, K.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. Roseburia Intestinalis Inhibits Interleukin-17 Excretion and Promotes Regulatory T Cells Differentiation in Colitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 7567–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Cheng, Y.; Ruan, G.; Fan, L.; Tian, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, D.; Wei, Y. New Pathway Ameliorating Ulcerative Colitis: Focus on Roseburia Intestinalis and the Gut–Brain Axis. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 17562848211004469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Bao, Z.; Gui, X.; Li, A.N.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.D. Clostridiales Are Predominant Microbes That Mediate Psychiatric Disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 130, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hong, X.L.; Sun, T.T.; Huang, X.W.; Wang, J.L.; Xiong, H. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Exacerbates Colitis by Damaging Epithelial Barriers and Inducing Aberrant Inflammation. J. Dig. Dis. 2020, 21, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, C.G.; Sperandio, V. Interplay Between the QseC and QseE Bacterial Adrenergic Sensor Kinases in Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2012, 80, 4344–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.T.; Clarke, M.B.; Yamamoto, K.; Rasko, D.A.; Sperandio, V. The QseC Adrenergic Signaling Cascade in Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). PLOS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, K.J.; Nemeroff, C.B. Role of Serotonergic and Noradrenergic Systems in the Pathophysiology of Depression and Anxiety Disorders. Depress. Anxiety 2000, 12 (Suppl. S1), 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, G.; Zeng, X.; Yue, H.; Zheng, Q.; Hu, Q.; Tian, Q.; Liang, L.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Z.; et al. The Norepinephrine-QseC Axis Aggravates F. Nucleatum-Associated Colitis Through Interkingdom Signaling. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Li, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, D.-D.; Wu, S.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.-J.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Anxiety, Depression, and Other Mental Disorders as Well as the Protective Effects of Dietary Components. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Xu, J.; Wu, D.; Chen, N.; Liu, Y. Gut Microbiota in Different Treatment Response Types of Crohn’s Disease Patients Treated with Biologics over a Long Disease Course. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.; Ding, B.; Feng, C.; Yin, S.; Zhang, T.; Qi, X.; Lv, H.; Guo, X.; Dong, K.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Prevotella and Klebsiella Proportions in Fecal Microbial Communities Are Potential Characteristic Parameters for Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malan-Müller, S.; Valles-Colomer, M.; Palomo, T.; Leza, J.C. The Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis in a Spanish Population in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Microbiota Composition Linked to Anxiety, Trauma, and Depression Profiles. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2162306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.; Gong, X.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Dong, Q. Involvement of Reduced Microbial Diversity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 6951091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdelbadiee, S.; Yoon, G.; Pearman, K.; Kumar, A.; Harvey, P.R. Understanding How Mental Health Influences IBD Outcomes: A Review of Potential Culprit Biological Mechanisms. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122916

Abdelbadiee S, Yoon G, Pearman K, Kumar A, Harvey PR. Understanding How Mental Health Influences IBD Outcomes: A Review of Potential Culprit Biological Mechanisms. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122916

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdelbadiee, Sherif, Giho Yoon, Kate Pearman, Aditi Kumar, and Philip R. Harvey. 2025. "Understanding How Mental Health Influences IBD Outcomes: A Review of Potential Culprit Biological Mechanisms" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122916

APA StyleAbdelbadiee, S., Yoon, G., Pearman, K., Kumar, A., & Harvey, P. R. (2025). Understanding How Mental Health Influences IBD Outcomes: A Review of Potential Culprit Biological Mechanisms. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2916. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122916