REDD1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Under Hypoxia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tissues and Cell Lines

2.2. Regents and Antibodies

2.3. Immunocytochemistry

2.4. Cell Transfection

2.5. Cell Proliferation Assay

2.6. Cell Apoptosis Assay

2.7. Cell Migration Assay

2.8. Colony Formation Assay

2.9. Western Blot Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. REDD1 Is Upregulated in Lung Adenocarcinoma

3.2. REDD1 Downregulation Suppresses Proliferation of LUAD Cells Under Hypoxia

3.3. Silencing of REDD1 Promotes A549 and H1299 Cell Apoptosis Under Hypoxia

3.4. Cell Migration and Colony Formation Are Suppressed After REDD1 Knockdown Under Hypoxia

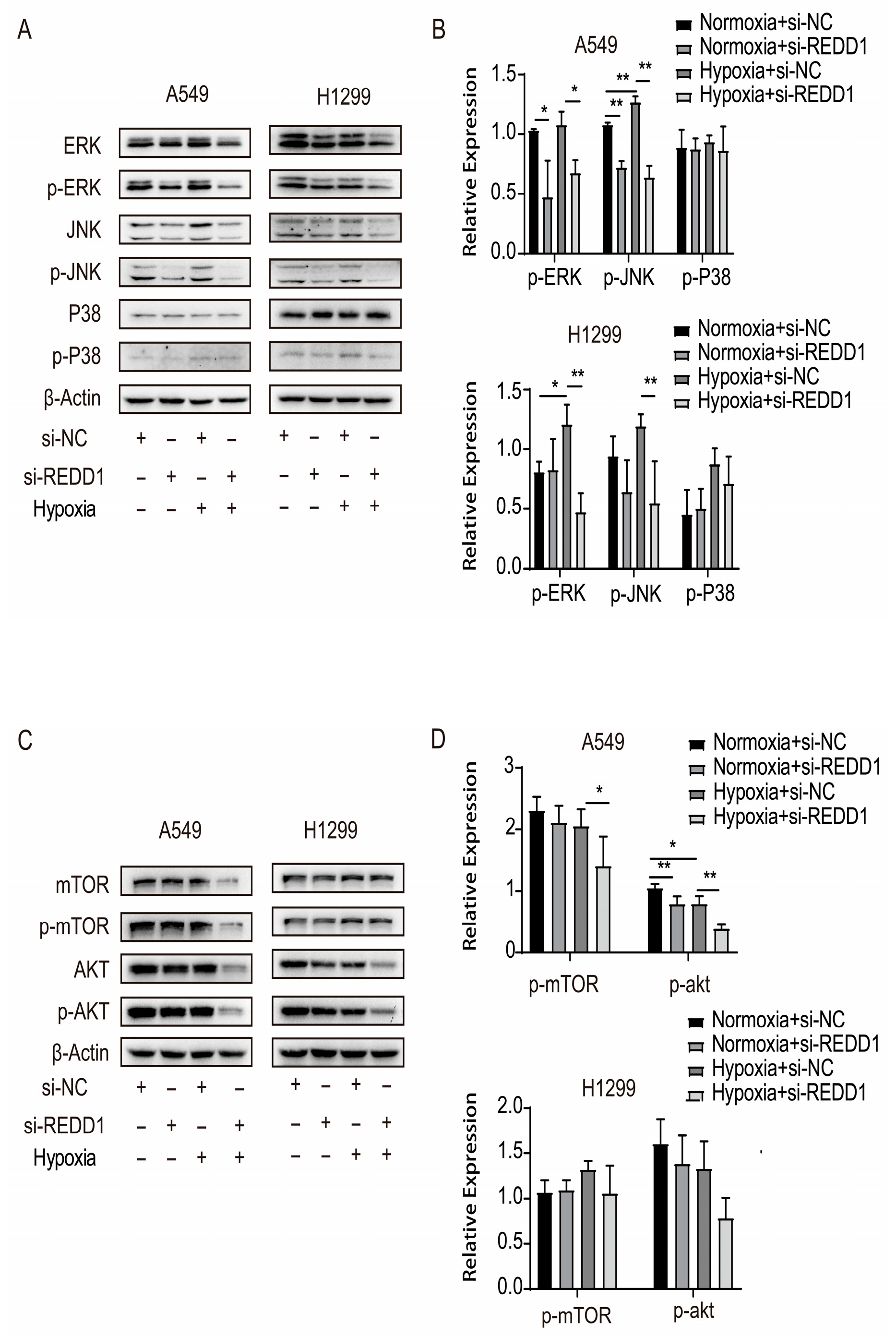

3.5. Variation in Signaling Cascade Protein Expression After REDD1 Knockdown

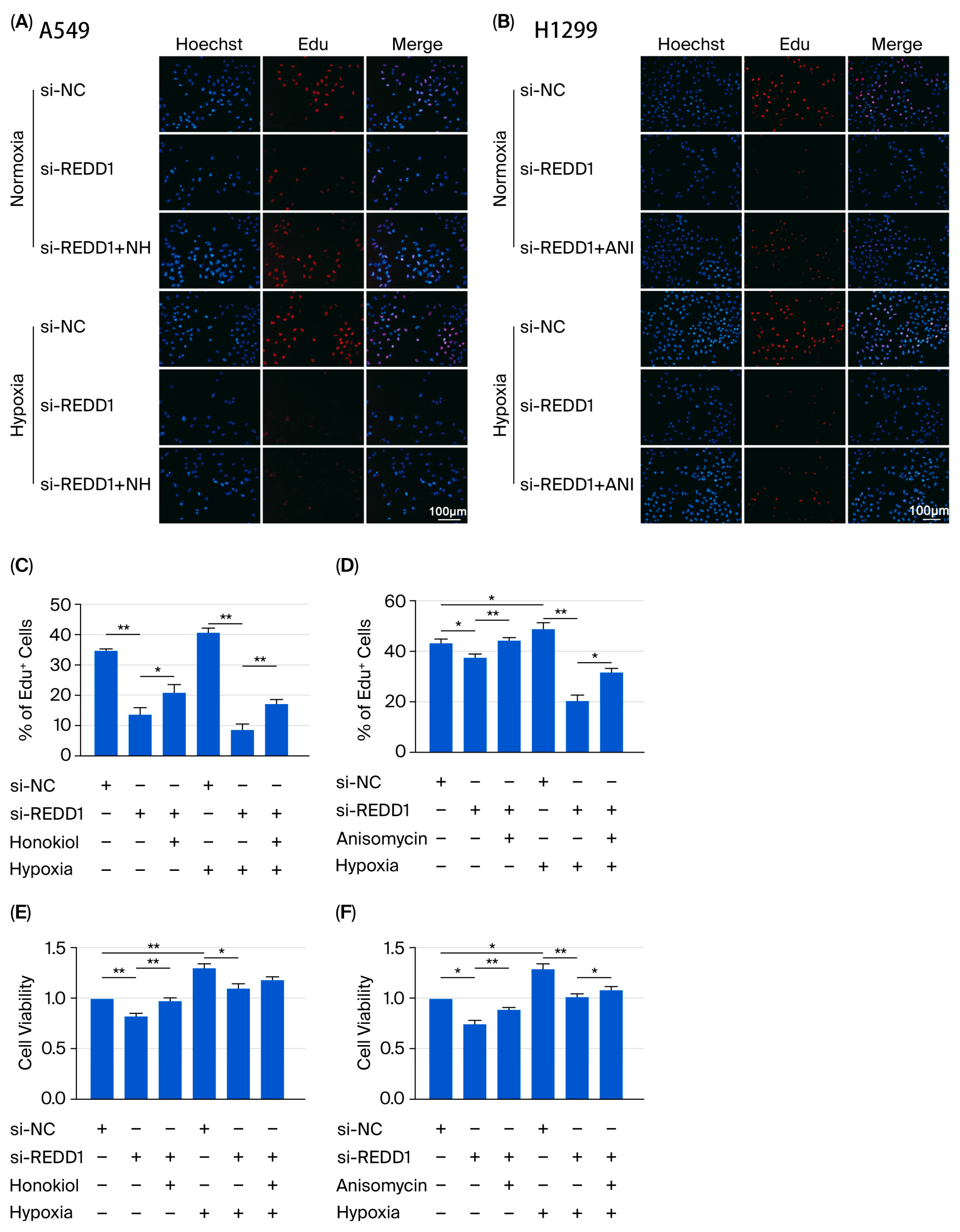

3.6. REDD1 Regulates LUAD Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation Via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling Under Hypoxia

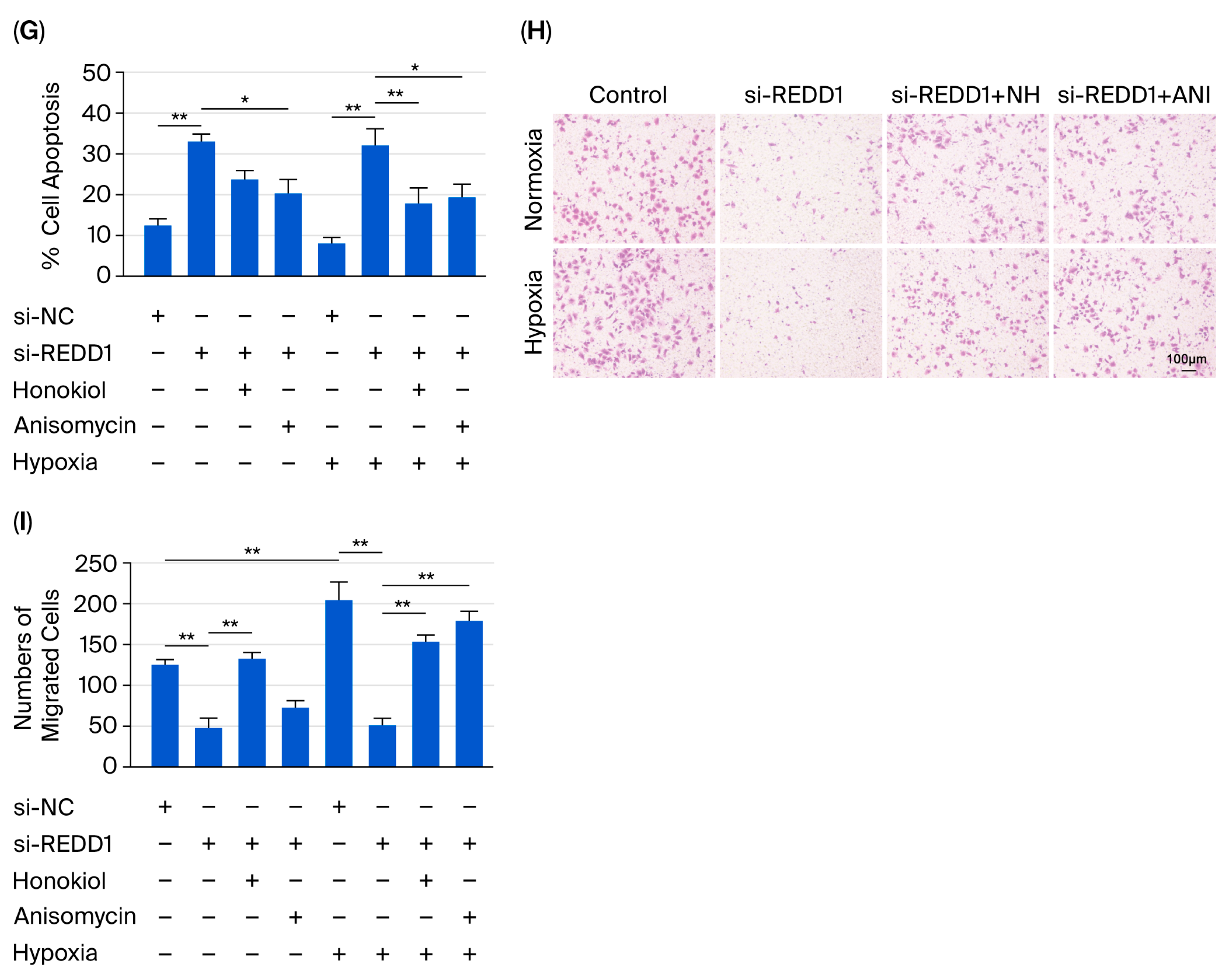

3.7. REDD1 Overexpression Regulates Cell Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation in Normoxic A549 and H1299 Cells

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridelli, C.; Rossi, A.; Carbone, D.P.; Guarize, J.; Karachaliou, N.; Mok, T.; Petrella, F.; Spaggiari, L.; Rosell, R. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, F.R.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Mulshine, J.L.; Kwon, R.; Curran, W.J., Jr.; Wu, Y.L.; Paz-Ares, L. Lung cancer: Current therapies and new targeted treatments. Lancet 2017, 389, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Leighl, N.B.; Wu, Y.L.; Zhong, W.Z. Emerging therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Fan, S.; Wu, M.; Zuo, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, L.; Shen, Q.; Xu, P.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, Y.; et al. YTHDF1 links hypoxia adaptation and non-small cell lung cancer progression. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, S. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α/vascular endothelial growth factor signaling activation correlates with response to radiotherapy and its inhibition reduces hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in lung cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018, 119, 7707–7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.; Unger, E. Overcoming tumor hypoxia as a barrier to radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy in cancer treatment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 6049–6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Wei, M.; Zhao, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, G. Identification of a novel glycolysis-related gene signature that can predict the survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Cycle 2019, 18, 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marisa, L.; Svrcek, M.; Collura, A.; Becht, E.; Cervera, P.; Wanherdrick, K.; Buhard, O.; Goloudina, A.; Jonchère, V.; Selves, J.; et al. The Balance Between Cytotoxic T-cell Lymphocytes and Immune Checkpoint Expression in the Prognosis of Colon Tumors. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Sai, B.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, G.; Tang, J.; Xiang, J. Hypoxic BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs promote metastasis of lung cancer cells via STAT3-induced EMT. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe-Seyler, K.; Bossler, F.; Lohrey, C.; Bulkescher, J.; Rösl, F.; Jansen, L.; Mayer, A.; Vaupel, P.; Dürst, M.; Hoppe-Seyler, F. Induction of dormancy in hypoxic human papillomavirus-positive cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E990–E998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Oeck, S.; Zhang, G.J.; Schramm, A.; Glazer, P.M. Hypoxia Induces Resistance to EGFR Inhibitors in Lung Cancer Cells via Upregulation of FGFR1 and the MAPK Pathway. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 4655–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoshani, T.; Faerman, A.; Mett, I.; Zelin, E.; Tenne, T.; Gorodin, S.; Moshel, Y.; Elbaz, S.; Budanov, A.; Chajut, A.; et al. Identification of a novel hypoxia-inducible factor 1-responsive gene, RTP801, involved in apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 2283–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.S.; Steiner, J.L.; Rossetti, M.L.; Qiao, S.; Ellisen, L.W.; Govindarajan, S.S.; Eroshkin, A.M.; Williamson, D.L.; Coen, P.M. REDD1 induction regulates the skeletal muscle gene expression signature following acute aerobic exercise. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2017, 313, E737–E747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, T.; Zhu, F.; Deng, S.; Li, X.; He, Y. Regulatory roles of miR-22/Redd1-mediated mitochondrial ROS and cellular autophagy in ionizing radiation-induced BMSC injury. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, M.; Lee, J.; Kang, H. Hypoxia-induced regulation of mTOR signaling by miR-7 targeting REDD1. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 4523–4532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B.; Meng, J.; Zhu, H.; Du, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Yang, G. Overexpression of the recently identified oncogene REDD1 correlates with tumor progression and is an independent unfavorable prognostic factor for ovarian carcinoma. Diagn. Pathol. 2018, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Q.; Liu, J.; Cao, P.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Fan, X.; Liu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Xiong, W.; Li, J.; et al. Inhibition of REDD1 Sensitizes Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma to Paclitaxel by Inhibiting Autophagy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, J.A.; Rolfo, C.; Raez, L.E.; Prado, A.; Araujo, J.M.; Bravo, L.; Fajardo, W.; Morante, Z.D.; Aguilar, A.; Neciosup, S.P.; et al. In silico evaluation of DNA Damage Inducible Transcript 4 gene (DDIT4) as prognostic biomarker in several malignancies. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.O.; Hong, S.E.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, M.R.; Chang, Y.H.; Hong, Y.J.; Lee, J.K.; Park, I.C. Induction of HSP27 and HSP70 by constitutive overexpression of Redd1 confers resistance of lung cancer cells to ionizing radiation. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 41, 3119–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.M.; Woo, S.H.; Oh, S.T.; Hong, S.E.; Choe, T.B.; Ye, S.K.; Kim, E.K.; Seong, M.K.; Kim, H.A.; Noh, W.C.; et al. Melatonin enhances arsenic trioxide-induced cell death via sustained upregulation of Redd1 expression in breast cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 422, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Jia, Y.; Yang, J.; Du, K.; Luo, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, B. PCAT19 Regulates the Proliferation and Apoptosis of Lung Cancer Cells by Inhibiting miR-25-3p via Targeting the MAP2K4 Signal Axis. Dis. Markers 2022, 2022, 2442094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duma, N.; Santana-Davila, R.; Molina, J.R. Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Epidemiology, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 1623–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisenko, T.V.; Budkevich, I.N.; Zhivotovsky, B. Cell death-based treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbst, R.S.; Morgensztern, D.; Boshoff, C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature 2018, 553, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Yang, F.; Shao, C.; Wei, K.; Xie, M.; Shen, H.; Shu, Y. Role of hypoxia in cancer therapy by regulating the tumor microenvironment. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erler, J.T.; Cawthorne, C.J.; Williams, K.J.; Koritzinsky, M.; Wouters, B.G.; Wilson, C.; Miller, C.; Demonacos, C.; Stratford, I.J.; Dive, C. Hypoxia-mediated down-regulation of Bid and Bax in tumors occurs via hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent and -independent mechanisms and contributes to drug resistance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 2875–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schito, L.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors: Master Regulators of Cancer Progression. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 758–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, D.; Taniguchi, C.M. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) in the tumor microenvironment: Friend or foe? Sci. China Life Sci. 2017, 60, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhihua, Y.; Yulin, T.; Yibo, W.; Wei, D.; Yin, C.; Jiahao, X.; Runqiu, J.; Xuezhong, X. Hypoxia decreases macrophage glycolysis and M1 percentage by targeting microRNA-30c and mTOR in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2019, 110, 2368–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, K.; Yadav, S.S.; Katz, A.A.; Seger, R. The Nuclear Translocation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases: Molecular Mechanisms and Use as Novel Therapeutic Target. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.F.; Nebreda, A.R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.P.; Yang, C.; Mihailescu, M.L.; Moore, J.A.; Dai, W.; Barber, A.J.; Dennis, M.D. Deletion of the Akt/mTORC1 Repressor REDD1 Prevents Visual Dysfunction in a Rodent Model of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes 2018, 67, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; He, Y. REDD1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Under Hypoxia. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122918

Fang X, Wang X, Liu X, He Y. REDD1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Under Hypoxia. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122918

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Xiaoyu, Xuezhao Wang, Xiansheng Liu, and Yuanzhou He. 2025. "REDD1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Under Hypoxia" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122918

APA StyleFang, X., Wang, X., Liu, X., & He, Y. (2025). REDD1 Affects Proliferation, Apoptosis, Migration, and Colony Formation via p-ERK and p-JNK Signaling in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells Under Hypoxia. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2918. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122918