Abstract

Thin films of fluorinated chromium phthalocyanine were prepared using spin coating techniques and annealed at 100, 200, 300, and 400 °C. The prepared films were investigated using UV-Visible absorption spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and atomic force microscopy. The band gap characteristics were evaluated to study the difference electronic transitions between the prepared thin films under different annealing temperatures. Films were exposed to ammonia vapor in a concentration range of 40–100 ppm to demonstrate the gas sensing activity of prepared devices. Resistance versus voltage behavior was investigated upon the exposure of ammonia gas and the samples show an increase in the resistance towards the existence of ammonia molecules. The dependency of the sensors on time was studied to evaluate the response and recovery time, which were found to be 10 and 13 s respectively.

1. Introduction

Over the past few years, there has been an increasing demand for simple and effective methods to detect toxic odors that are produced by organic volatile compounds, due to their damaging effects on biological systems and the environment in general [1,2,3]. Among these hazardous gases, amines complexes are commonly used in agricultural, pharmaceutical, dye manufacturing, and food processing industries [4,5,6,7,8]. Ammonia (NH3) is a toxic gas present in large quantities of air, soil, and water. Exposure to low concentrations (25–150 ppm) of ammonia might lead to the irritation of human skin, eyes, and the respiratory tract. Moreover, exposure to high ammonia concentrations (>5000 ppm) severely affects human health and can eventually lead to death [9]. Therefore, the monitoring of ammonia in the gas phase is a very urgent problem in various applications, from industrial hygiene and environmental protection in chemical industry to clinical diagnostics, etc. [10]. Thus far, a huge variety of chemical sensors of ammonia have been proposed, including those based on inorganic, inorganic oxide/dioxide, and conducting polymers [11,12].

Phthalocyanines (Pcs) in general and their metallo-derivatives (MPcs), in particular, constitute a family of medium sized molecular organic p-type semiconductors. Pcs hold a great promise for the development of numerous applications, such as chemical sensors, fuel cells, solar cells, and optoelectronic devices [13,14,15]. Another advantage of MPcs is their process-ability in thin films structure, which means the possibility to deposit these compounds utilizing different ways, such as spin-coating, drop-casting, thermal evaporation, and Langmuir–Blodgett techniques [16,17]. The improvement of organic semiconductor devices relies on the quality of the metal–organic interfaces [18], in particular, on the efficiency of charge injection and on the mobility of the charge carriers [19]. Moreover, thin films of MPcs are promising for gas sensing applications, due to their high chemical and thermal stability and noticeable variations of both conductivity and optical properties upon sorption of analyte gases [11].

Phthalocyanines, both unsubstituted (H2Pc) and metal complexes (MPcs), are organic p-type semiconductors widely used as chemiresistive gas sensors. Moreover, thin films of MPcs are promising for gas sensing applications, due to their high chemical and thermal stability and noticeable variations of both conductivity and optical properties upon sorption of analyte gases [11]. It is worth mentioning that both the sensitivity and response of MPcs to various analytes were found to depend on the nature of the metal atom and substituents in the aromatic ring, as well as on the structure and molecular organization in the thin films [18]. Therefore, the peripheral substitution of the conjugated macrocycle of MPcs by electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups is an easy way to vary the sensitivity and selectivity of their films toward different analytes [19]. More specifically, the electron-withdrawing fluorine peripheral substituents alter the sensitivity of the MPc species toward reducing gases [13]. For instance, fluorinated zinc phthalocyanine turned out to be less sensitive to oxidizing gases (SO2 and NO2) and more sensitive to reducing gases (e.g., NH3 and H2) [20]. The current work focuses on the characterization of fluorinated chromium phthalocyanine thin films and their ability to detect ammonia gas as a resistance-based device.

2. Materials and Methods

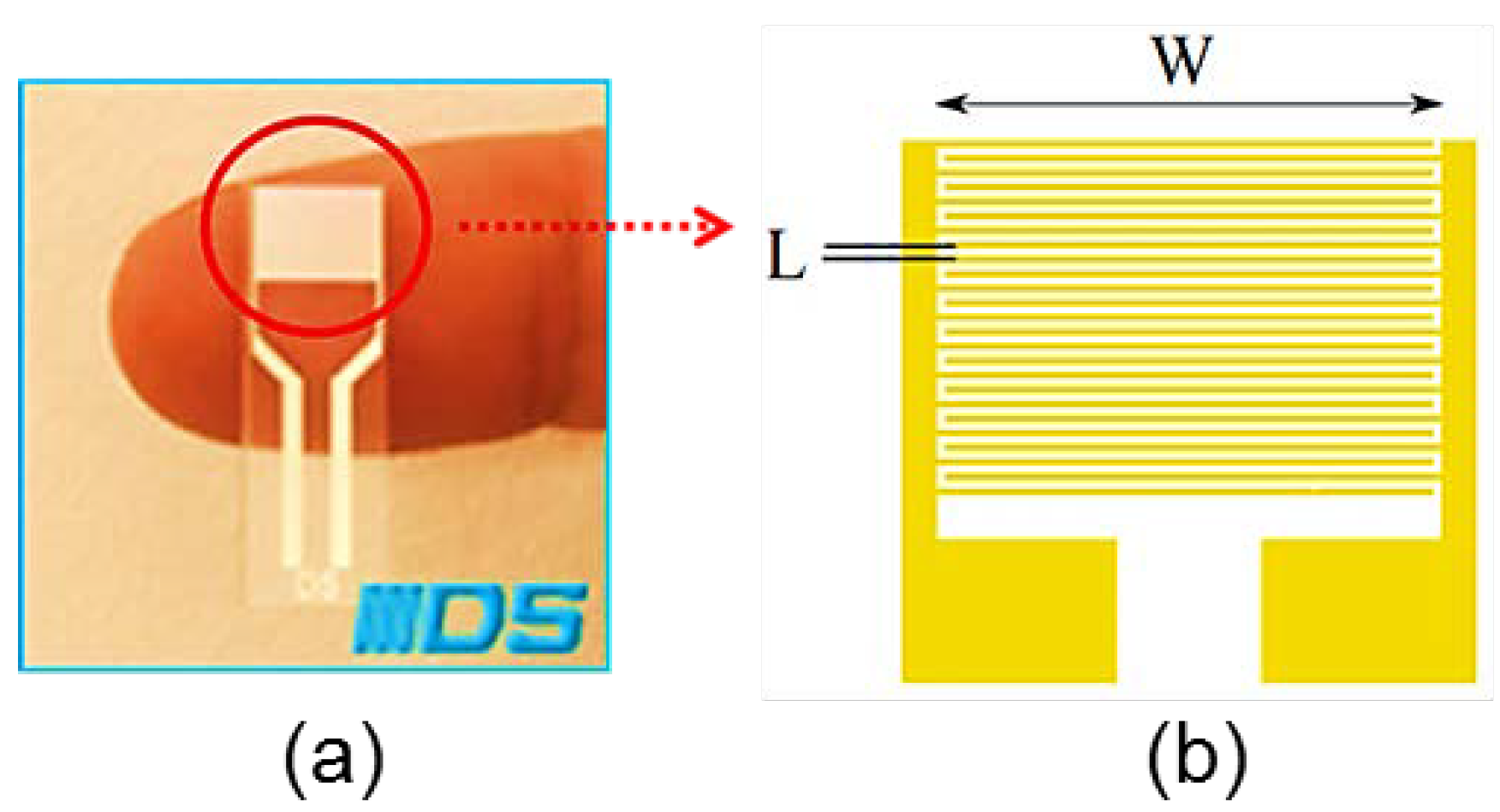

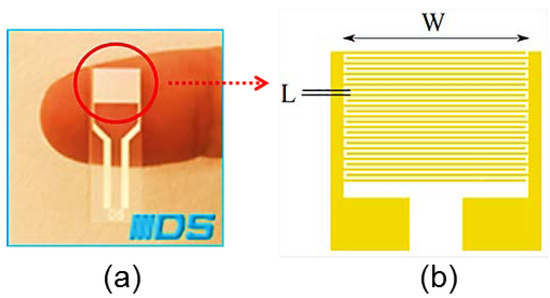

Thin films of fluorinated chromium phthalocyanine (FCrPc) were prepared as active thin films for sensor applications; FCrPc was synthesized according to a published technique [21]. FCrPc was dissolved in trifluoroacetic-acid (TFA) in the concentration of 1 mg mL−1. The mixture was sonicated for 15 min and then filtered to obtain a homogenous solution. Thin films of FCrPc were prepared via spin coating; thin films were annealed at 100, 200, 300, and 400 °C. Spun films were deposited onto glass slides (supplied by Sigma Aldrich, Hamburg, Germany, plain, size 25 × 75 mm) for UV-Vis absorption studies, while Si substrates (n-type semiconductor, orientation (100) supplied by Wafer World, West Palm Beach, FL, USA) were used for Atomic Force Microscope (AFM) measurements and commercial interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) from Drop-sense company were used for the electrical and sensor measurements. The dimensions of the IDEs are the following: W is the overlapping distance between the fingers (7 mm), n is the number of fingers (250) and L is the space between electrodes (5 μm), as demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

(a) Interdigitated electrodes (IDE) and (b) sketch diagram of the IDE.

3. Characterization Techniques

The prepared thin films were examined using different techniques, such as UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy, Raman spectra, an atomic force microscope (AFM), and other electrical measurements. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Varian 50-scan UV–visible) in the range of 190–1100 nm was used to measure the absorption spectra. Raman spectra were recorded with a Triplemate, SPEX spectrometer equipped with a Charge Coupled Device CCD detector in back-scattering geometry. The 488 nm, 40 mW line of Ar-laser was used for the spectral excitation. The morphologies of synthesized thin films were determined by a Nanoscope IIIa multimode atomic force microscope (Bruker-AFM). The electrical characteristics and the time dependency results were measured using LabVIEW software interfaced with 2400 Kiethley Sourcemeter.

4. Results and Discussion

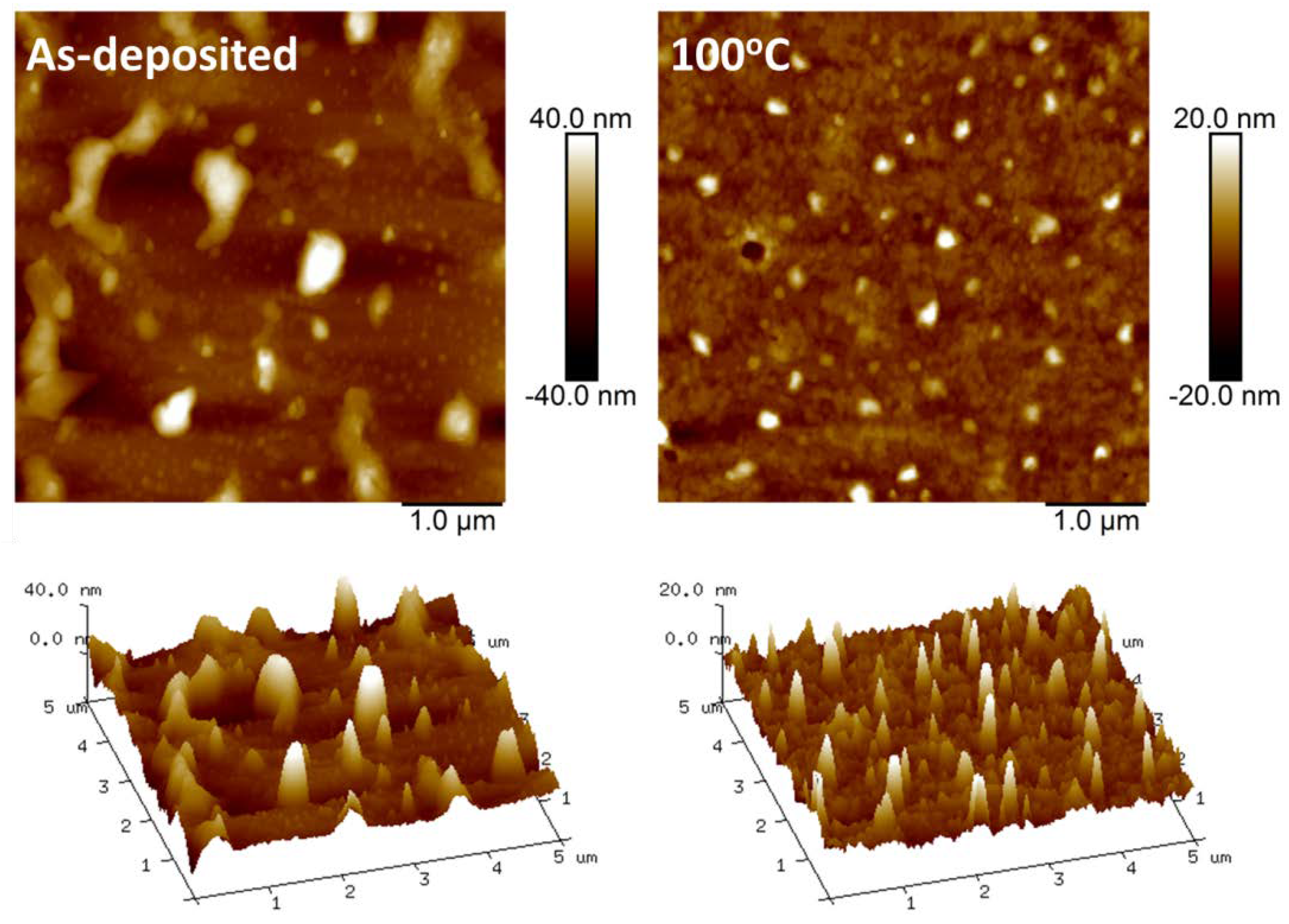

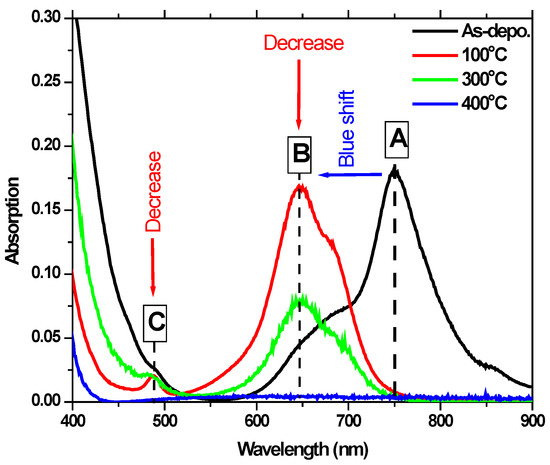

4.1. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

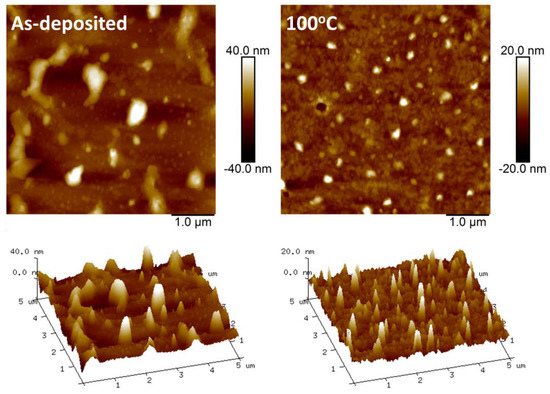

AFM measurements in tapping mode were performed on all samples in this study. Figure 1 shows the typical aggregation features of phthalocyanine thin film. Phthalocyanine and almost all organic dyes tend to make very dense aggregations in the solid state. These aggregates are represented as a coplanar association of rings which develope from monomer to dimer and higher order complexes. They are driven by π–π interaction and van der Waals forces [22].

It can clearly be seen that the surface of FCrPc as deposited thin film (Figure 2) is less homogeneous than that of heat-treated films and that the surface roughness has decreased significantly after annealing (Ra = 6.8, 5.5, 3.1 and 1.7 nm for the as deposited, and heated to 100, 300 and 400 °C respectively). This suggests that heating above the transition temperature of metallo-phthalocyanine would rearrange the molecules on the substrate surface and break the hindrance of large bundles upon deposition—as the samples were spun from their volatile solutions. It was shown earlier that the spin-coating method provides a simple and convenient procedure for preparing ordered films of the phthalocyanines which can be heated to form thin liquid-crystalline films [23,24].

Figure 2.

Atomic force microscope (AFM) images of fluorinated chromium phthalocyanine (FCrPc) deposited and treated with different temperatures.

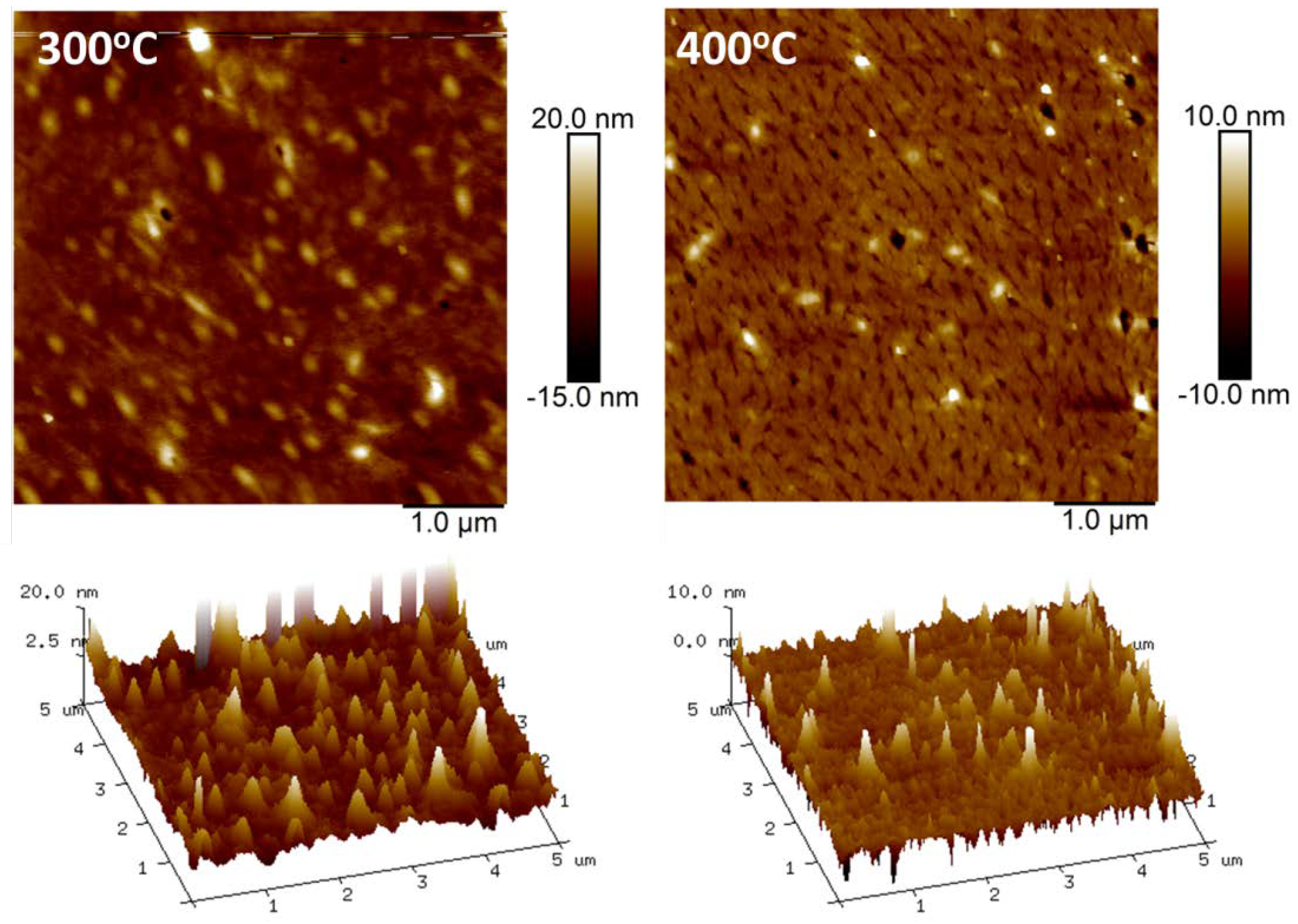

4.2. UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy

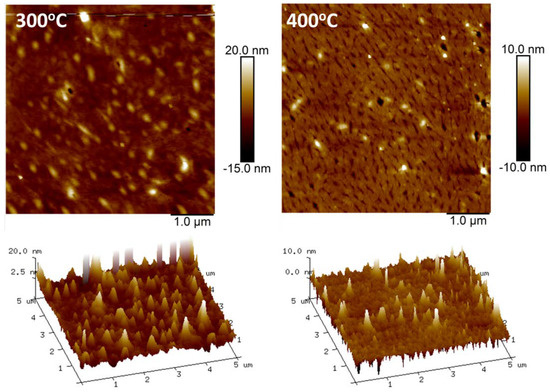

UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded on a Varian 50 scan UV-Visible spectrophotometer. The electronic absorption spectra of the films of FCrPc before and after heating are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Absorption spectra of FCrPc deposited and treated with different temperatures.

The Q-band structure is more complex than that observed in the as deposited films where a single main band is assigned to the doubly degenerate transition a1u-eg. In the optical spectra of heated FCrPc thin films the main absorption bands are broadened through exciton coupling effects, which also lead to shifts in the band positions. These are dependent upon molecular packing [25]. The spectra of the films after heating are blue shifted, relative to the spectra of the monomers. From these spectral changes, it can be deduced that on passing from crystal to mesophase, changes into parallel (face-to-face) dimer stacking are observed. This type of re-organization is analogous to that undergone by the octaalkyl analogues upon transition from the crystal phase to the hexagonal discotic mesophase [26,27].

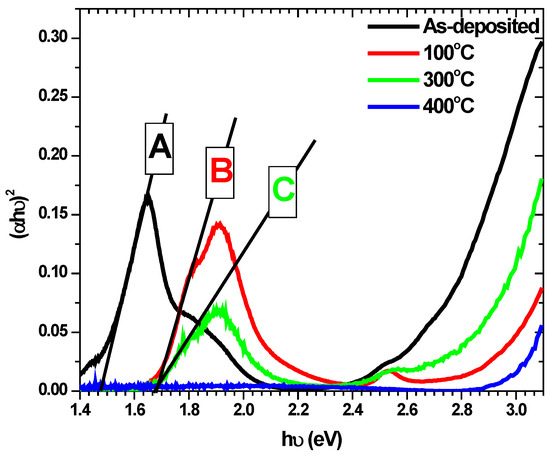

4.3. Band Gap Determination

The absorption coefficient (α) for a semiconductor can be estimated using the following equation [28]:

where T is the transmittance and d is the film thickness. The optical band-gap is related to the absorption coefficient (α) and photon energy (hν) and can be calculated using the following relation [29]:

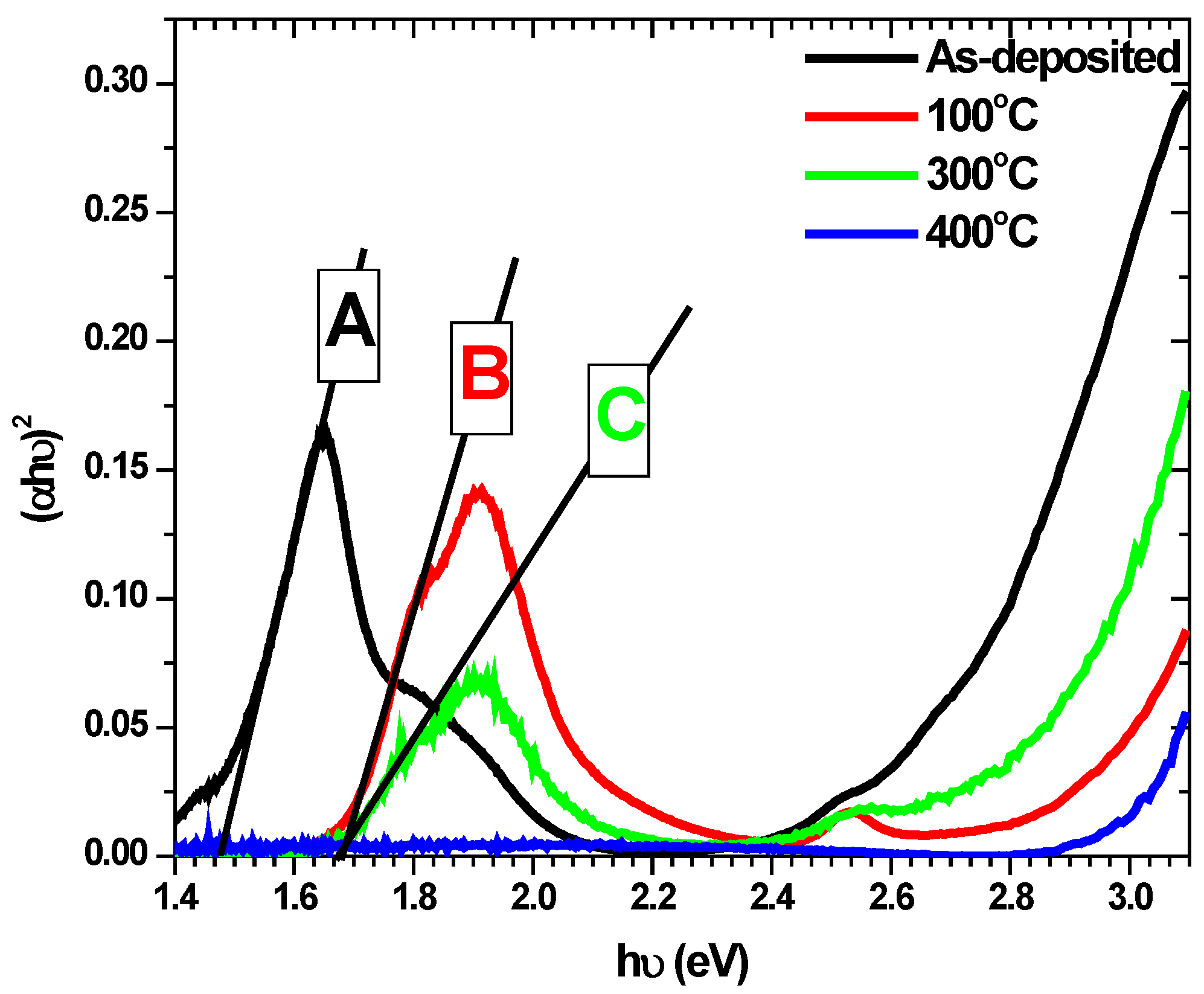

where A is a constant, is the absorption coefficient, h is Plank’s constant, and ν is the frequency. The index n identifies the type of electronic transition between the energy bands; the values of ½ and 2 are related to direct and indirect transitions respectively [30]. The optical band gap is evaluated from the plot of (αhν)2 as a function of photon energy (hν) and then by extrapolating the linear regions of the plots to zero absorption [30] as shown in Figure 4. The band gaps revealed a clear blueshift upon annealing the thin films from 1.49 eV in the as deposited FCrPc to 1.6 eV in the FCRPc thin films treated at 100 and 300 °C. The films’ growth upon annealing treatment changes the carrier concentration and this change is strictly affected Eg [31].

Figure 4.

Plot of (αhν)2 versus photon energy (hν) of FCrPc deposited and treated with different temperatures.

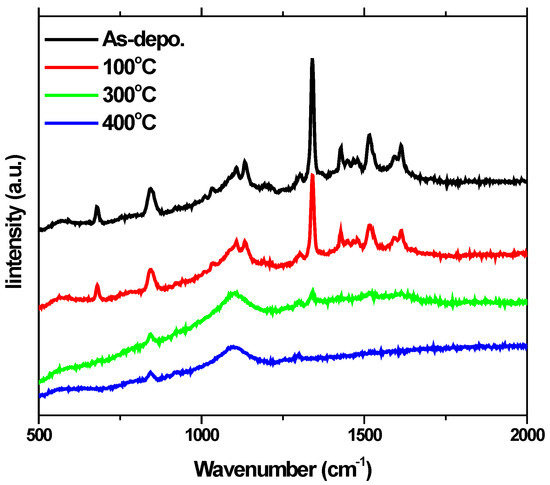

4.4. Raman Spectra

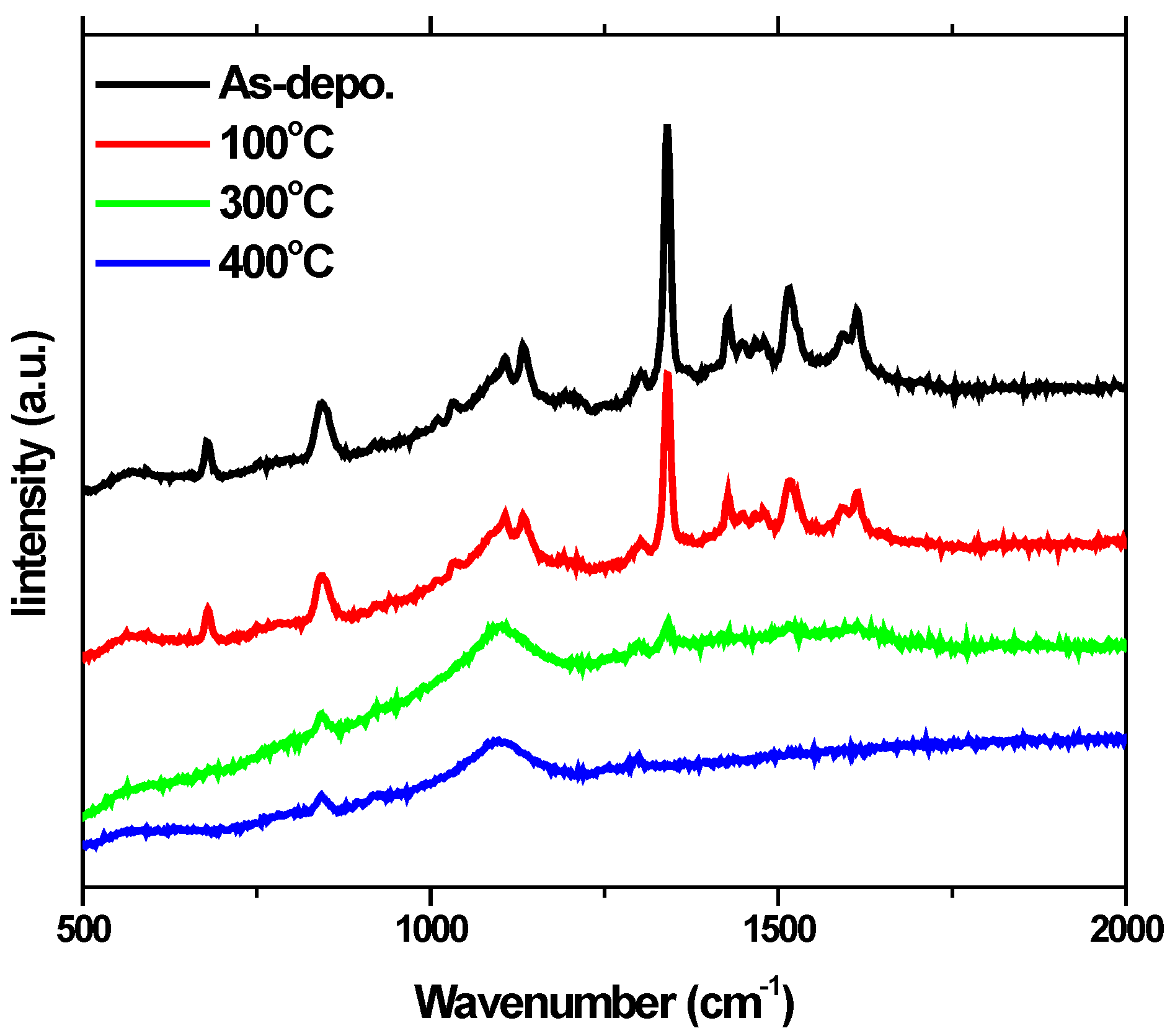

The Raman spectra of FCrPc thin films deposited on quartz substrates in parallel (ii) and cross (ij) polarizations are shown in Figure 5. It has already been shown that there are intensive bands belonging to organic substituents in the range 1300 cm−1 in Raman spectra of substituted phthalocyanines, due to the resonance character of the Raman spectra excited by the lasers of the visible region [32]. After heating above 300 °C, this band has disappeared, due to the disappearance of the stretching vibration of the Pc macrocycle.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra of FCrPc deposited and treated with different temperatures.

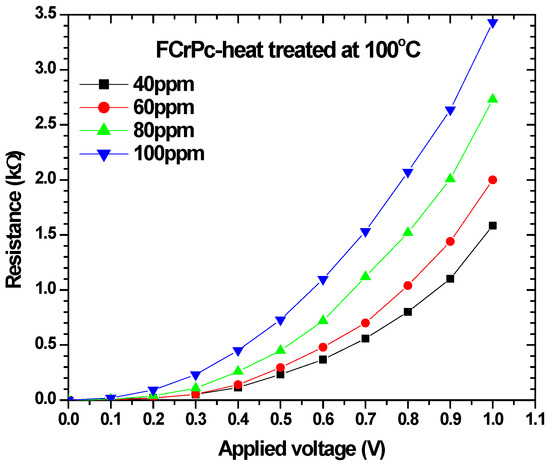

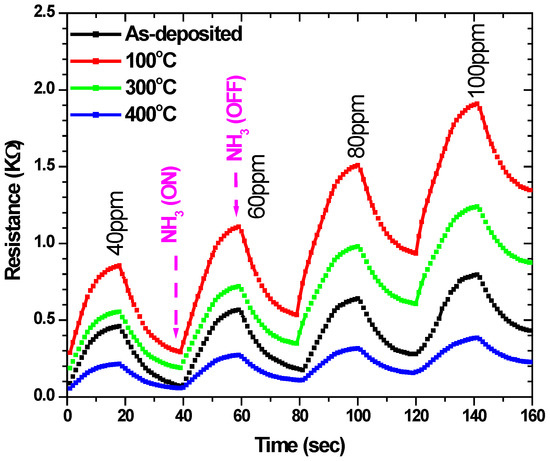

4.5. FCrPc Films Interaction with Amonia Gas

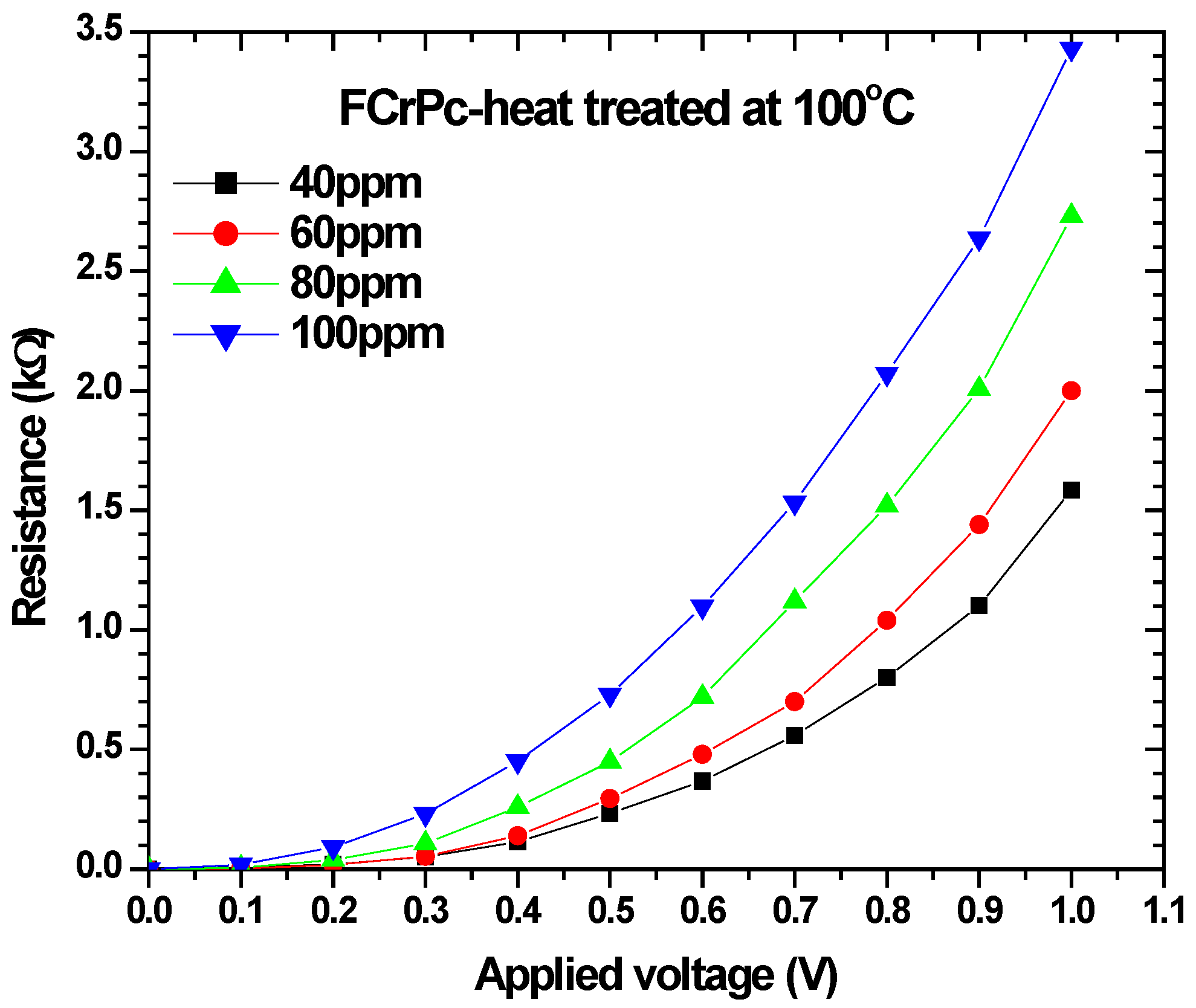

FCrPc thin films have been deposited on interdigitated electrodes (IDE) to study the voltage-resistance characteristics (V-R) and the time dependent resistance in a fresh and contaminated air ambient to demonstrate the sensor activity of the studied material. All films have been exposed to concentrated NH3 gas to demonstrate the best annealing temperature. Samples heated to 100 °C showed better sensitivity towards the ammonia gas. This could be due to the higher surface area for the rougher films. Figure 6 represents the V-R curves of FCrPc thin film heated at 100 °C in the NH3 concentrations ranging from 40 to 100 ppm. We observe that the interaction of prepared samples with ammonia gas results in an increase of resistance, which could be due to the reductive nature of ammonia towards strong donors.

Figure 6.

Resistance versus Applied Voltage (R-V) characteristics of FCrPc deposited and treated at 100 °C with different NH3 concentrations.

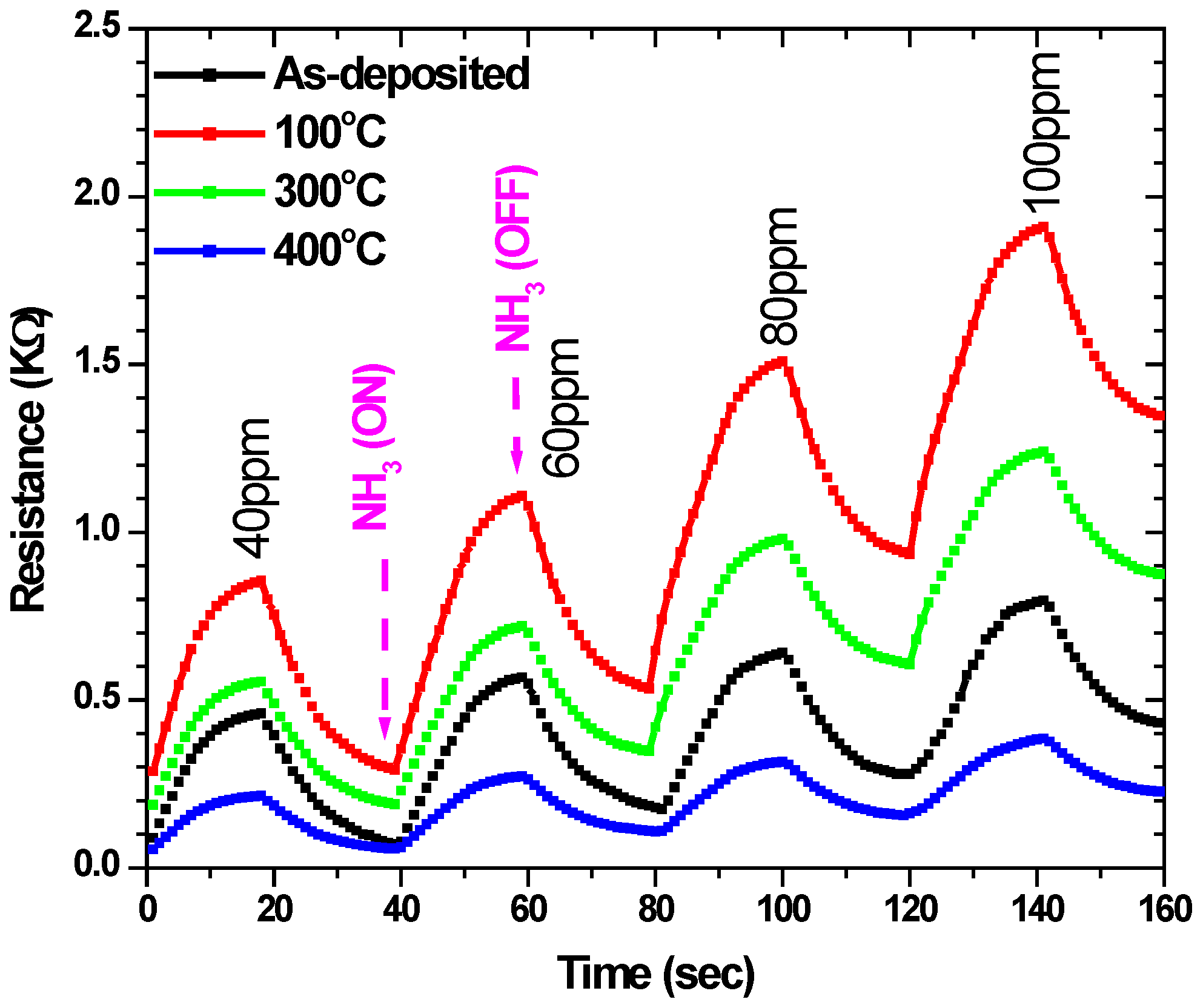

A common model is based on the fact that phthalocyanine thin films consist of a large number of grains which are in contact at their boundaries. The electrical behavior is governed by the formation of potential barriers at the interface of adjacent grains, caused by charge trapping at the interface. The size of this barrier determines the conductance. When exposed to a chemically reducing gas, like ammonia, electrons withdraw, leading to an increase in the resistance [33]. The time dependency of the FCrPc device showed a reasonable stability in regard to time, upon the exposure of ammonia gas (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Time dependency of FCrPc films upon exposure to ammonia at concentrations ranging from 40 to 100 ppm.

The response and recovery time, which are defined as the time it takes to reach 80% of the steady state and the time required to reach 80% of the base line respectively, were found to be 10 and 13 s. The prepared samples were found to be reproducible and the performance due to contaminations was the same after 30 days of preparation.

5. Conclusions

FCrPc solution in TFA was spun onto glass, silicon, interdigitated electrodes, and films that were heat treated at different annealing temperatures. The roughness of the films decreased significantly at higher temperatures due to the de-bundling effect. In the optical spectra, the main absorption bands are broadened after heating through exciton coupling effects which also lead to shifts in the band positions. The sensitivity of the thin films towards ammonia vapor has increased with the rise of annealing temperatures and the response and recovery time of the sensor has found to be 10 and 13 s respectively.

Author Contributions

H.A.B. contributed in evaluating, measuring and writing most of the manuscript. B.Y.K. has contributed in the preparation and characterization of the thin films as well as part of writing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Materials and Engineering Research Institute, Sheffield Hallam University for helping in the AFM, electrical and sensing measurements.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lee, H.; Jatoi, A.W.; Kyohei, Y.; Kim, K.O.; Song, K.H.; Lee, J.; Zhu, C.; Tsuiki, H.; Kim, I.S. Deodorant activity of phthalocyanine complex nanofiber. Text. Res. J. 2018, 88, 630–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomo, G.; Nwaji, N.; Nyokong, T. Low symmetric metallophthalocyanine modified electrode via click chemistry for simultaneous detection of heavy metals. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2018, 813, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lucena, N.C.; Miyazaki, C.M.; Shimizu, F.M.; Constantino, C.J.; Ferreira, M. Layer-by-layer composite film of nickel phthalocyanine and montmorillonite clay for synergistic effect on electrochemical detection of dopamine. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 436, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banimuslem, H.; Hassan, A.; Basova, T.; Yushina, I.; Durmuş, M.; Tuncel, S.; Esenpınar, A.A.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Copper phthalocyanine functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes: Thin film deposition and sensing properties. Key Eng. Mater. 2014, 605, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banimuslem, H.; Hassan, A.; Basova, T.; Gülmez, A.D.; Tuncel, S.; Durmus, M.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Copper phthalocyanine/single walled carbon nanotubes hybrid thin films for pentachlorophenol detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 990–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.; Hassan, A.; Yuksel, F.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Optical detection of pentachlorophenol in water using thin films of octa-tosylamido substituted zinc phthalocyanine. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2010, 150, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, A.K.; Tardy, J.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Bessueille, F.; Jaffrezic-Renault, N.; Lemiti, M. Trimethylamine biosensor based on pentacene enzymatic organic field effect transistor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 263302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.; Zhan, F.; Jiang, H.; Xing, Z.; Fang, C. Facile production of self-assembly hierarchical dumbbell-like COOH nanostructures and their room-temperature CO-gas-sensing properties. Cryst. Growth Des. 2008, 8, 3497–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryer, J.E. Helth effect of ammonia. Plant. Oper. Prog. 1991, 10, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmer, B.; Olthuis, W.; Van den Breg, A. Ammonia sensors and their applications—A review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2005, 107, 666–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Gu, C.; Yu, K.; Mrng, F.; Liu, J. A novel highly sensitive gas ionization sensor for ammonia detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2009, 150, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, G.; Yu, J.; Chen, X. Fabrication and gas sensitivity of polyaniline-titanium dioxide nanocomposite thin film. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2007, 125, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, M.; Eckern, U.; Romero, A.; Schwingenschlogl, U. Electronic transport properties of (fluorinated) metal phthalocyanine. New J. Phys. 2016, 18, 013003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, M. Green approaches to highly selective processes: Reactions of dimethyl carbonate over both zeolites and base catalysts. Pure Appl. Chem. 2007, 79, 1855–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Joshi, N.; Samanta, S.; Singh, A.; Debnath, A.K.; Chauhan, A.K.; Roy, M.; Prasad, R.; Roy, K.; Chehimi, M.M.; et al. Room temperature detection of H2S by flexible gold–cobalt phthalocyanine heterojunction thin films. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 206, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banimuslem, H.; Hassan, A.; Basova, T.; Esenpınar, A.A.; Tuncel, S.; Durmuş, M.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Dye-modified carbon nanotubes for the optical detection of amines vapours. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 207, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banimuslem, H.; Hassan, A.; Basova, T.; Durmus, M.; Tuncel, S.; Esenpınar, A.A.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Copper Phthalocyanine Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: Thin Films for Optical Detection. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 15, 2157–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, A.; Barger, W. Phthalocyanine films in chemical sensors. In Phthalocyanine Properties and Applications; Leznoff, A., Ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 1989; pp. 341–392. [Google Scholar]

- Miyata, T.; Kawaguchi, S.; Ishii, M.; Minami, T. High sensitivity chlorine gas sensors using Cu phthalocyanine thin films. Thin Solid Films 2003, 425, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohrer, F.I.; Colesniuc, C.N.; Park, J.; Schuller, I.K.; Kummel, A.C.; Trogler, W.C. Selective detection of vapor phase hydrogen peroxide with phthalocyanine chemiresistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 3712–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evyapan, M.; Kadem, B.; Basova, T.V.; Yushina, I.V.; Hassan, A.K. Study of the sensor response of spun metal phthalocyanine films to volatile organic vapors using surface plasmon resonance. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Chen, Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.; Blau, W.; Zhu, J. Preparation and optical limiting properties of multiwalled carbon nanotubes with -conjugated metal-free phthalocyanine moieties. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 13029–13035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.; Koltsov, E.; Gurek, A.; Atilla, D.; Ahsen, V.; Hassan, A. Investigation of liquid crystalline behavior of copper oktakisalkylthiophthalocyanine and its film properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2008, 28, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.; Durmus, M.; Ahsen, V.; Hassan, A. Effect of interface on the orientation of the liquid crystalline nickel phthalocyanine films. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 19251–19257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, B.; Li, H.; McKeown, N. The control of molecular self-association in spin-coated films of substituted phthalocyanines. J. Mater. Chem. 2000, 10, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatsusaka, K.; Ohta, K.; Yamamoto, I.; Shirai, H. Discotic liquid crystals of transition metal complexes, part 30: Spontaneous uniform homeotropic alignment of octakis(dialkoxyphenoxy)phthalocyaninatocopper(II) complexes. J. Mater. Chem. 2001, 11, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.; Gurek, A.; Ahsen, V. Investigation of liquid-crystalline behavior of nickel octakisalkylthiophtahlocyanines and orientation of their films. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2002, 22, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.W.; Jeon, D.W.; Sahoo, T.; Kim, M.; Baek, J.H.; Hoffman, J.L.; Kim, N.S.; Lee, I.H. Effect of annealing temperature on optical band-gap of amorphous indium zinc oxide film. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 10062–10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadem, B.; Hassan, A.; Cranton, W. Efficient P3HT: PCBM bulk heterojunction organic solar cells; effect of post deposition thermal treatment. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 7038–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Sagar, P.; Mehra, R.M. Band gap widening and narrowing in moderately and heavily doped n-ZnO films. Solid-State Electron. 2006, 50, 1420–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burstein, E. Anomalous optical absorption limit in InSb. Phys. Rev. 1954, 93, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basova, T.V.; Kolesov, B.A.; Gürek, A.G.; Ahsen, V. Raman polarization study of the film orientation of liquid crystalline NiPc. Thin Solid Films 2001, 385, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, R.; Lal, P.; Dwivedi, R. Sensing mechanism in tin oxide-based thick film gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B 1994, 21, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).