1. Introduction

Population growth-induced food security and nutritional challenges are among the significant problems in many countries [

1]. Under such a scenario, the supply of nutritious food has been considered a major global issue, especially for the economically weaker section of the population [

2]. In 2023, approximately 713 to 757 million people, or one in eleven, experienced hunger globally. As per the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 2.5 billion adults and 149 million children under the age of 5 in 2022 experienced malnutrition [

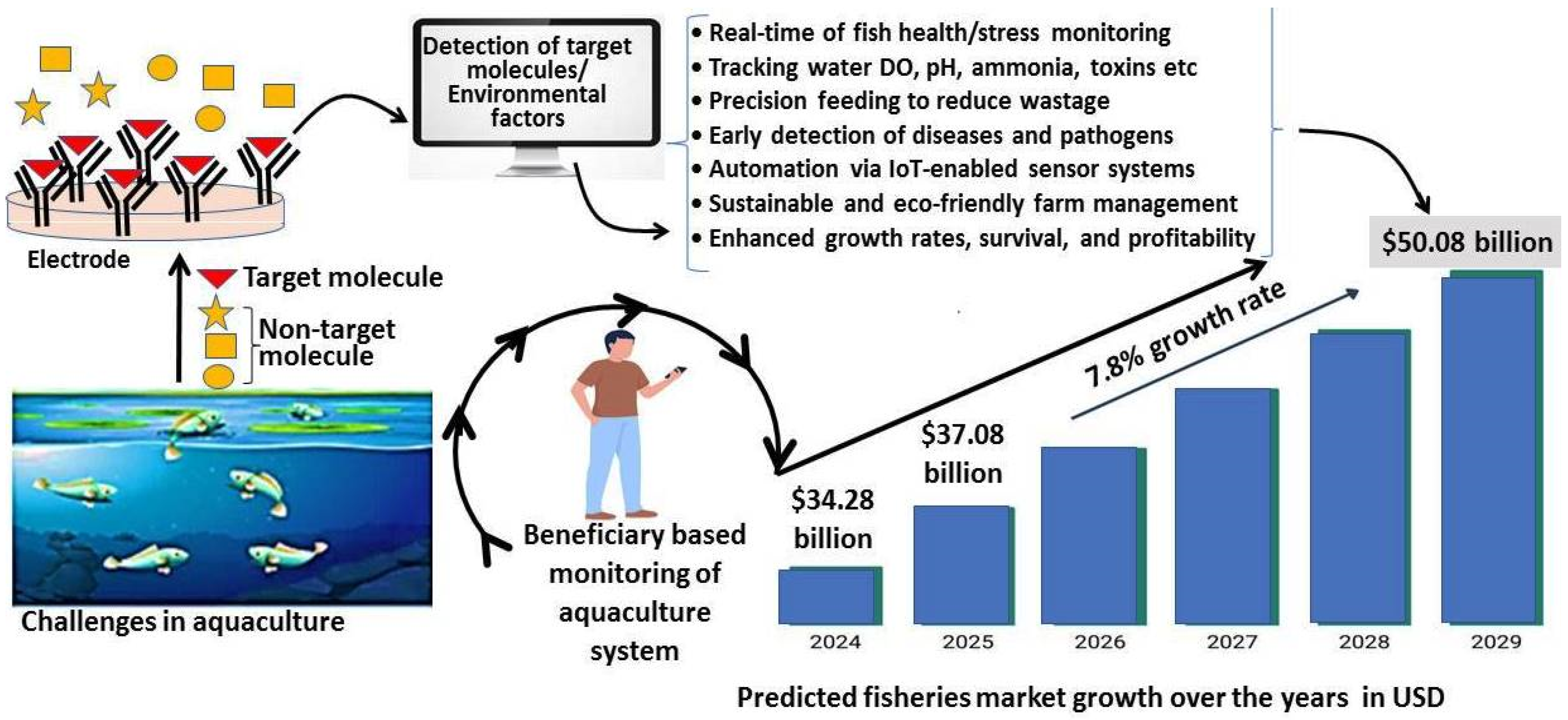

3]. This marks the beginning of the blue revolution in aquaculture worldwide, as fish meat is considered an accessible and affordable source of food for economically weaker sections of the population. Therefore, the use of modern technology, such as bio(sensors), to meet the challenges observed in the aquaculture sector to increase production is required [

3].

The use of modern technology in aquaculture, including biosensors, over the last few decades, could be a reason for the enhanced production [

4,

5]. The UN’s latest edition of The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA), published in 2024, states a 4.4% global expansion of fisheries and aquaculture, accounting for 223.3 million tonnes, from 2022 to 2024 [

3]. The recent production of aquatic animals amounts to an astonishing value of 185.4 million tonnes, compared to 37.8 million tonnes of algal species [

6]. This was predicted to meet the demand for digestible fish protein, addressing global food scarcity among economically weaker sections [

7]. Global aquaculture production has increased threefold in response to current demands over the last twenty-five years. It has surpassed any other food industry and has successfully established itself as a massive international industry, constantly growing in leaps and bounds [

8,

9]. Asia became the leading player in the aquaculture industry, accounting for more than 91% of the total production in 2017, with an annual growth rate of 5.89%. The second position was occupied by the American continent with a yearly increase in the rate of 5.45% per annum in this industry, followed by Europe, accounting for 2.7% of global production at an increase rate of 2.7% per annum, and lastly the African continent, although producing 2% of the worldwide output but a higher rate of increase at 9.81% per year since 2000 [

10]. The most significant factors contributing to the massive expansion of the aquaculture industry are the rise in global demand for fish consumption and the adoption of modern technologies, including biosensors [

11]. For example, various problems, including toxicity form aminophenol in

Labeo rohita fingerlings [

12] and meloxicam in

Cyprinus carpio [

13], have already been proven to decrease fish farming production. Early detection can be used to adopt the appropriate measures utilizing modern technology against infections, diseases, pollution, and toxicity. The adoption of such technology in fish farming has led to its double expansion over the last 50 years, supassing meat and pork consumption by a significant margin [

3,

14,

15]. The fish food industry is dominated by inland freshwater fish farming, which accounted for approximately 62% of the global live-weight volume and three-fourths of the global edible-weight volume in 2020 [

3,

9]. Although the most significant contributors to this industry are inland fishes, it also includes other marine organisms, ranging from the tiny unicellular

Chlorella algae [

16] to Atlantic salmon (

Salmo salar) [

3].

Although the above data explain the ever-evolving and flourishing aquaculture industry, which has thrived for centuries, it faces numerous challenges in detecting and managing problems at various levels, including environmental issues, seed production, supply chain management, pollution, disease outbreaks, and mismanagement of coastal areas [

17,

18]. Aquatic flora and fauna face alarming threats from human interventions, including oil spills, ocean warming, overexploitation, eutrophication, and the introduction of invasive species [

19]. Advances in modern technology have introduced biosensors as promising tools for the early detection and timely management of crises detected in aquatic systems. Biosensors are analytical devices that detect chemical reactions between analytes and bioreceptors, with a transducer converting the bio-recognition signal into a measurable value [

20]. Recent developments include point-of-care biosensors, which enable the immediate application of remedial measures at the site to minimize contamination following human intervention [

21,

22]. Biosensors offer early, continuous, and real-time monitoring of environmental parameters, facilitating the detection of stress or disease in aquatic organisms [

23]. Conventional methods often fail to provide timely data acquisition, which is essential for effective fish farm management. Although most biosensors in biomedical sciences are primarily developed for clinical applications, such as in cancer and organ disorder detection [

24,

25], their use in fish farms has been limited to areas like disease detection and quality control [

26,

27]. Therefore, it was hypothesized that a comprehensive, updated review focusing specifically on biosensors used in fish aquaculture could help clarify their significance in the sector. This article examines advancements in the application of biosensor technologies in aquaculture, focusing on pathogen detection, informed decision-making, optimized feeding strategies, enhanced animal welfare, and sustainable aquaculture practices. It also critically examines existing limitations, emphasizing the potential of biosensor adoption to revolutionize the aquaculture industry.

2. Search Strategy

To review the topic of biosensors in fish aquaculture, a literature survey was conducted primarily in electronic databases. Major scientific electronic databases, including PubMed, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, Agricola, Google Scholar, and Scopus, were searched using relevant keywords. The keywords were mainly focused on fish and fisheries, with an addendum of words such as “challenges,” “disease,” “sensor,” “biosensor,” “marine water,” and “fresh water.” The published articles in the search results were only included in the study. Articles that merely contained any of the relevant terms but were out of the scope of the topic were excluded. Similarly, articles published in languages other than English were also excluded from the review. Articles that fell under the scope of the current review were included in the review, irrespective of the journal, book, chapter, religion, author, region, race, or country of publication. Authentic websites, such as those of the FAO and WHO, were also considered for the current review to gather information, facts, and figures about biosensors and aquaculture production in fish farming.

3. Current Status in Aquaculture

In 1987, 10 million tonnes of farmed fish and shellfish were cultivated, a figure that increased threefold to 29 million tonnes by 1997, alongside approximately 300 farmed species. It further increased to 80 million tonnes in 2017, which included 425 farmed species [

3,

10]. About 31.8 million tonnes of aquatic plants, 17.4 million tonnes of mollusks, and 8.4 million tonnes of crustaceans were produced, accounting for 28.4%, 15.4%, and 7.5% of the total aquaculture production, respectively. About 422,124 tonnes of the smaller marine and freshwater invertebrates were also produced [

10]. Aquaculture provides 43% of the world’s aquatic fauna for human food consumption. It is expected that it will grow to address the future demand of the expanding population. Over the past 50 years, global aquaculture has experienced tremendous growth, increasing from approximately 52.5 million tonnes in 2008. The production was highest in Asia, accounting for 89% by volume and 79% by value [

28] (

Figure 1). The major product of the aquaculture industry is animal protein, which plays a crucial role in combating nutritional deficiencies and disorders. Edible products from the fisheries industry not only supply high-quality proteins but also essential vitamins, micronutrients, and minerals. For approximately 950 million people, fish remain the primary source of protein [

29]. In Asia, aquaculture generates significant economic returns annually, being USD 471.66 billion by China alone in 2024. Japan alone imports an estimated 5400–10,000 tonnes of jellyfish products each year. At the same time, aquaculture practices have expanded to countries such as Namibia, Australia, the USA, and the UK to meet the rising demand [

30].

In India, aquaculture exhibits an annual growth rate of approximately 7%, with catfish species accounting for 90% of total aquaculture production [

31]. Globally, aquaculture production reached 214 million tonnes in 2020, reflecting a 0.2% increase from 2019 but a 0.6% decrease compared to 2018, primarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic [

32]. Of this, aquatic animals for human consumption accounted for approximately 157 million tonnes. The total production from aquaculture comprised 87.5 million tonnes of aquatic animals intended for food. Other products include 35.1 million tonnes of seaweed and algae used for both food and non-food purposes, as well as 700 tonnes of shells and pearls designated for ornamental purposes. The rapid expansion of aquaculture, while addressing global nutritional demands, has also exposed the sector to emerging environmental and biological vulnerabilities [

1]. These challenges underscore the critical need for adaptive strategies and resilience-building measures within aquaculture systems [

4,

5,

11].

4. Challenges Associated with Aquaculture

The rapidly expanding aquaculture industry, with its rising demand for fishery products, poses numerous challenges; therefore, it requires attention to sustain production. Among the major threats, climate change is particularly significant [

33,

34]. Finfish and shellfish are directly impacted through unpredictable alterations in their physiological traits, while shifts in primary and secondary productivity indirectly affect their health and ecosystem structure [

33,

34,

35]. Rising sea levels and inland temperature fluctuations disrupt critical coastal ecosystems, such as mangroves and salt marshes, which lead to a decline in fish abundance and seed stock availability [

36].

Effects of climate change on aquaculture are attributed to geography, climate zone, economics, farming methods, and the species cultivated [

35,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Elevated temperature impairs the growth and development of aquatic animals, and prolonged thermal stress affects their endocrine and osmoregulatory systems [

44]. Changes observed in sea surface temperature trigger algal blooms that deplete dissolved O

2 and reduce reef fishery productivity through coral bleaching [

36]. The early detection of temperature patterns may mitigate such threats, at least in artisanal aquatic sectors, when fish are cultured in open seas. Additionally, an increase in atmospheric CO

2 levels leads to ocean acidification, resulting in a reduction in carbonate availability, which is crucial for the skeletal development of shell-forming organisms. As a result, it increases their vulnerability to predation and reduces their productivity [

41,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

Ocean acidification also increases production costs, forcing large producers to rely on hatcheries more frequently [

44]. Furthermore, global warming alters precipitation patterns, and excessive rainfall causes floods that introduce invasive species into aquaculture systems. It degrades water quality and increases predation risks [

44]. Conversely, drought intensifies stress on aquatic organisms. This leads to stock losses, elevated maintenance costs, and a reduction in overall production capacity [

36]. Rising sea levels, along with natural phenomena such as storms and cyclones, can exacerbate salinity intrusion. It poses a significant threat to aquaculture [

50]. Human activities, including coastal aquaculture operations, such as shrimp farming, also contribute to salinity intrusion, which has adverse effects on aquatic flora and fauna [

50,

51]. Ammonia toxicity, with LC50 concentrations ranging from 0.3 to 0.9 mg/L for cold-water fish, 0.7 to 3.0 mg/L for warm-water fish, 0.6 to 1.7 mg/L for marine fish, and 0.7 to 3.0 mg/L for marine shrimp, raises significant concerns in aquaculture [

52]. Ammonia levels are inversely related to dissolved O

2 levels, and their imbalance can lead to water eutrophication [

52]. Parasitic, bacterial, viral, and fungal infections also heavily impact aquaculture, leading to severe fish health conditions, such as pancreatic necrosis in salmonids [

53] and fin rot. In turn, it can cause severe tissue damage in Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout [

54].

Another critical but less attended issue is the need for sex control to stabilize mating systems, maintain fish quality, and prevent precocious maturation. Altogether or alone, these can reduce feeding rates and hinder growth [

55]. Production of mono-sex populations is desirable in species such as Nile tilapia, as males exhibit faster growth and better feed conversion efficiency compared to females [

56]. Stress is a significant factor that affects aquaculture, particularly in farmed fish, and induces adverse effects on growth, reproduction, immune function, and disease susceptibility [

57,

58]. Diet plays a crucial role in modulating stress sensitivity [

59], while feed quality, feeding rate, reproductive frequency, and male-to-female ratio are important for optimal growth and development [

60]. The use of advanced technology to address the aforementioned issues is believed to be essential for enhancing productivity in the aquaculture sector [

4,

5,

11]. Additionally, handling and transport are major stressors that indicate the need for stress-minimizing water quality management and oxygen maintenance during these processes [

61]. Many aquaculturists who lack resources and knowledge on pond preparation under climate change and the above-mentioned conditions bear huge losses [

36]. In such cases, the importance of early prediction of environmental or disease challenges and educating farmers on the use of modern technologies, including (bio)sensors, is crucial. Various obstacles to aquaculture are listed in

Table 1 and illustrated in

Figure 2. Given these operational challenges, the need for real-time monitoring and quality assessment technologies has become increasingly crucial in aquaculture systems.

Table 1.

Challenges to aquaculture and their effects.

Table 1.

Challenges to aquaculture and their effects.

| Challenges | Effects | References |

|---|

| Climate Change | Alters physical and physiological aspects of finfish and shellfish; changes in primary and secondary productivity; ecosystem structure alterations. | [33,34,35] |

| Sea-Level Rise and Inland Temperature Changes | Damages coastal ecosystems, mangroves, and salt marshes; reduces fish abundance and distribution. | [36] |

| Geographical and Climatic Variations | Varying impacts on aquaculture based on location, climate zones, economy, production systems, and species. | [35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Rising Temperatures | Affects growth and development of aquatic animals; impacts endocrine and osmoregulatory systems; leads to algal blooms, reducing dissolved oxygen; coral bleaching affects reef fisheries. | [36,44] |

| Ocean Acidification | Decline in pH-affecting shell-forming organisms like shrimps, mussels, oysters, and corals; increased vulnerability to predation; higher production costs due to reliance on hatcheries. | [41,44,45,46,47,48,49] |

| Changes in Precipitation Patterns | Increased rainfall, causing floods and introducing invasive species; droughts leading to water stress, stock loss, and higher maintenance costs. | [36,44] |

| Sea-Level Rise and Natural Phenomena | Salinity intrusions threatening aquaculture; anthropogenic activities, like shrimp farming, exacerbate salinity intrusion, affecting aquatic flora and fauna. | [50,51,62] |

| Ammonia Toxicity | Harmful effects on aquatic life; inverse relationship with dissolved oxygen; eutrophication due to imbalance in ammonia and nitrate levels. | [52,63,64] |

| Disease Outbreaks | Parasitic, bacterial, viral, and fungal diseases cause significant harm; examples include pancreatic necrosis in salmonids and fin rot in Atlantic salmon and rainbow trout. | [65,66,67,68] |

| Need for Sex Control | Ensures stability of mating systems; prevents precocious maturation; desire for mono-sex populations for better growth rates, e.g., male Nile tilapia grow faster. | [55,56] |

| Stress Factors | Negatively impacts growth, reproduction, and immune function; influenced by diet, handling, and transport; poor water quality and oxygen levels exacerbate stress. | [60,69,70] |

| Lack of Education and Awareness | Aqua culturists, who are often poor, are inadequately prepared to adapt to changes, making them vulnerable to impacts on fish resources. | [36] |

Figure 2.

Challenges associated with aquaculture (modified after Sarkar et al. [

71]).

Figure 2.

Challenges associated with aquaculture (modified after Sarkar et al. [

71]).

5. Biosensors

Since ancient times, humans have conducted bioanalysis using their senses, and the evolution of biosensors has advanced as an integrative tool for quality control, food safety, environmental impact assessment, and applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry [

72]. A biosensor typically integrates biological recognition components (bio-receptors) with a transducer system to efficiently detect specific compounds or conditions, offering rapid, low-cost, on-site detection compared to conventional, time-consuming methods [

72]. A standard biosensor comprises an analyte of interest; bioreceptors, such as enzymes, cells, aptamers, DNA, or antibodies that generate signals upon recognition; and a transducer that translates these signals in proportion to the analyte–bioreceptor interactions [

20]. Electrical components then convert the signal into a digital output, which is displayed on devices, such as Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) screens, computers, or printers in various forms, including numeric, graphic, tabular, or image formats [

20] (

Figure 3).

5.1. Types of Biosensors Used in Pisciculture

The performance and application of biosensors are highly influenced by the design and functionality of their transducer modules. Accordingly, biosensors are classified into various types based on the nature of the transducer used (

Table 2). Recent advancements in sensor technology have significantly enhanced detection accuracy, sensitivity, and operational stability, driving broader adoption across multiple domains, including aquaculture.

5.2. Mode of Detection

Various operation modules for specific types of biosensors are employed in aquaculture to address several challenges. Integrating specialized biosensor systems has enabled real-time monitoring of critical aquatic parameters that contribute to the sustainable management of aquaculture practices.

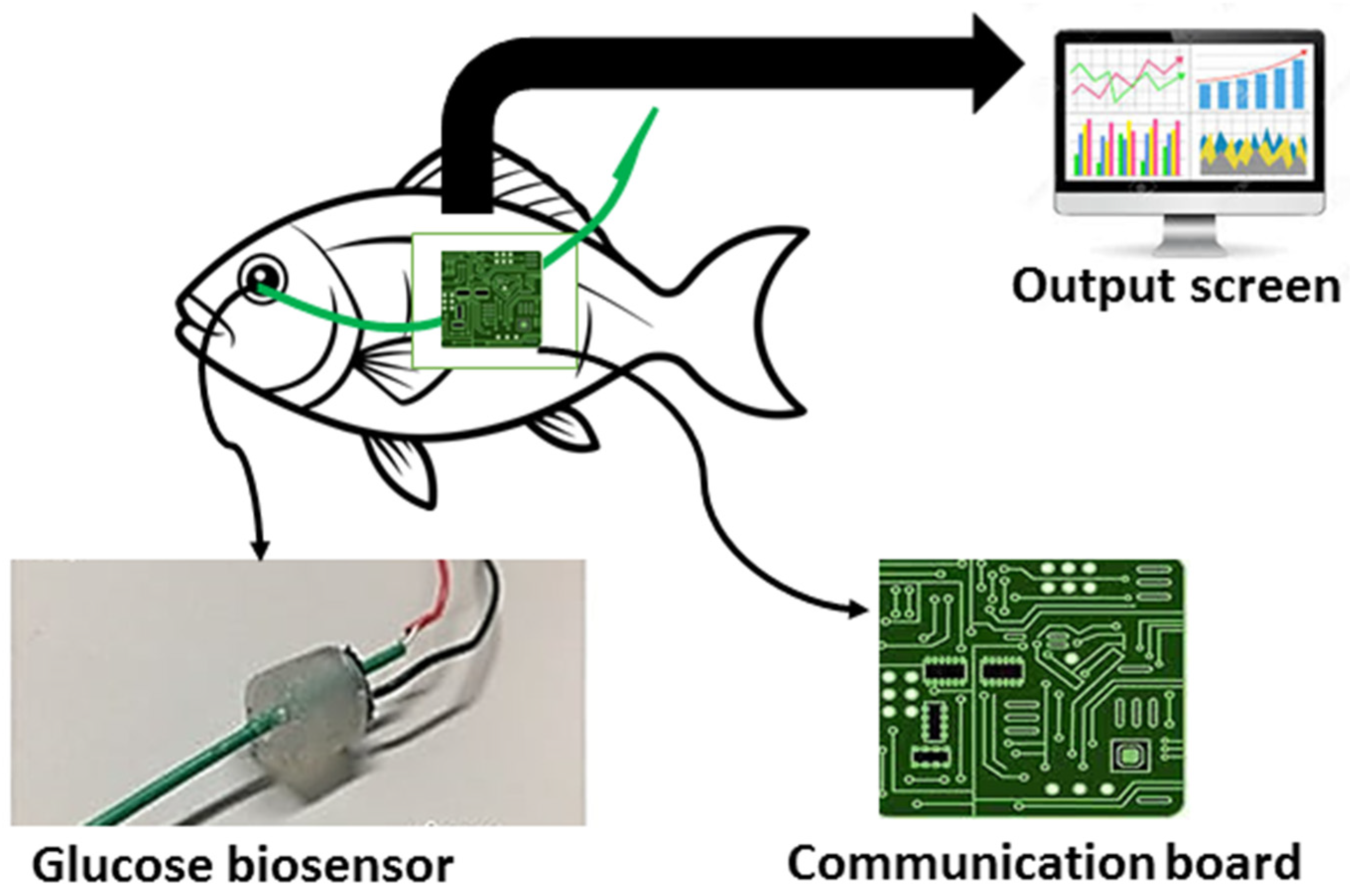

5.2.1. Wireless Sensor Network

Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs) have emerged as an alternative to conventional cable networks in aquaculture. These address challenges such as complexity, maintenance, and limitations on expansion [

83]. In 2011, researchers at Jiangsu University developed a WSN system capable of real-time measurement of six to seven water quality parameters, including dissolved O

2, pH, and temperature [

84]. The WSN operates according to the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) 802.15.4 standard, comprising sensor nodes, routing nodes, and a gateway node [

85]. A simplified model consists of three components: the WSN Unit (with sensor, routing, and gateway nodes placed in the fish pond), a monitoring unit (data and web servers), and a client network [

83]. Sensor nodes gather environmental data, routing nodes that optimize the transmission path to the gateway, and the collected information is processed by servers and relayed via the internet to authorized clients [

83] (

Figure 4). Recent advancements in nanotechnology have further enhanced the sensitivity and functionality of biosensing systems integrated into such networks, particularly through the application of nanoparticles. These developments introduce a new dimension to real-time aquatic monitoring, enabling the early detection of biological and chemical changes. In aquaculture, both environmental changes and changes induced by such changes in fish make them vulnerable to infection and death. For example, cold susceptibility of Nile tilapia (

Oreochromis niloticus) or high temperature-induced infection of reovirus in grass carp (

Ctenopharyngodon idella) [

86,

87]. Therefore, real-time monitoring of water parameters using WSN biosensors in aquaculture, combined with a client information alert system, is beneficial.

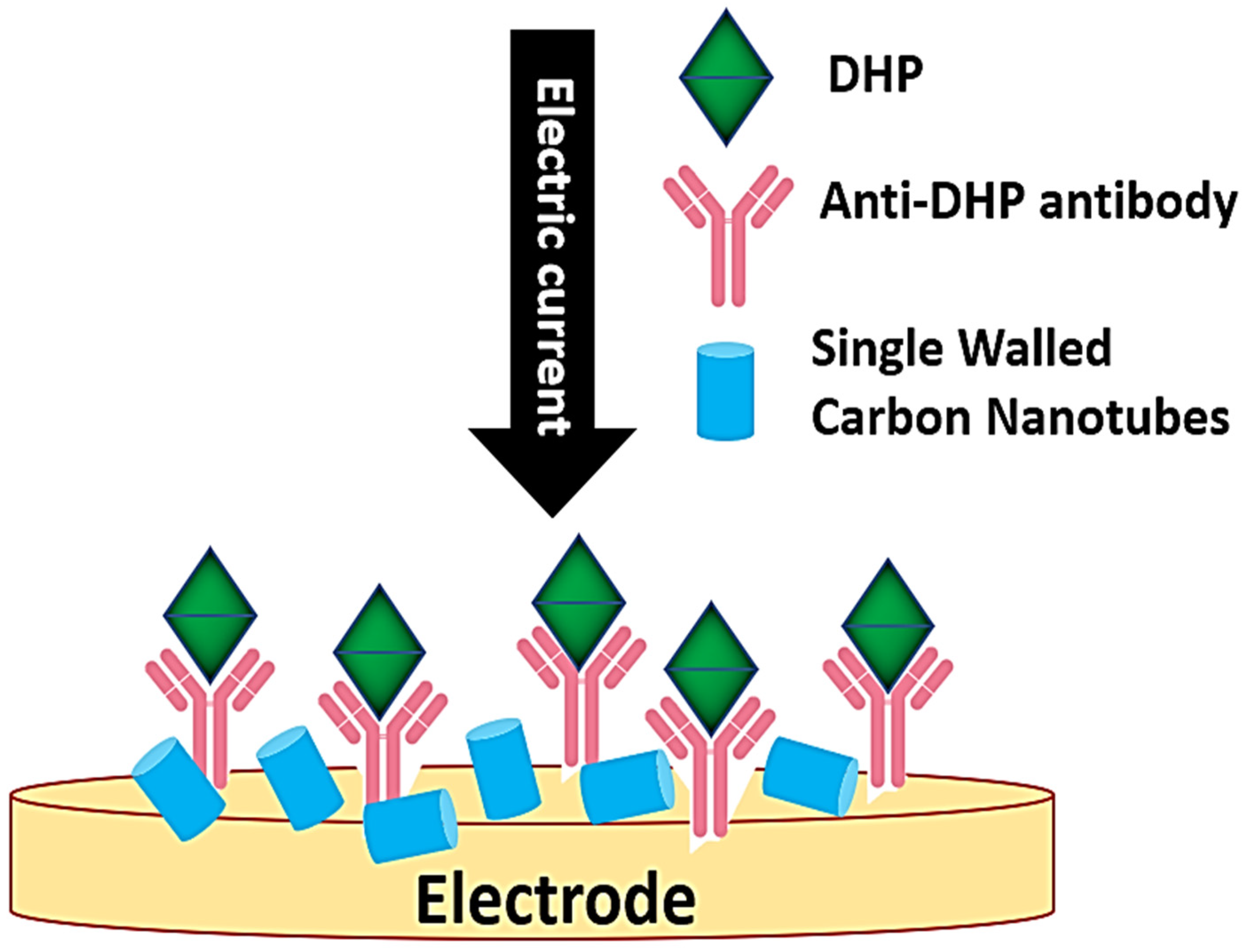

5.2.2. Nanoparticle Biosensor

Nanoparticles ranging in size from 10 to 500 nm possess a spherical, polymeric structure that offers a high surface-area-to-volume ratio. It enables their applications across fields, including in the aquaculture sector [

88]. They aid in disease detection, drug delivery, and the management of water quality. Designed nanosensors/-particles (diaminonaphthalene/Remazol Blue R-capped zinc oxide and carbon nanotubes) can help to detect hormones such as epinephrine in biological fluids [

89,

90]. Metal nanoparticles such as gold, silver, and platinum serve as ideal core materials due to their excellent conductivity and catalytic properties [

91,

92]. Interestingly, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) appear ruby red rather than gold, and their size inversely influences enzyme stability and biosensor sensitivity [

93]. Un-aggregated particles are ruby red, and their color varies with aggregation, whereas aggregated particles exhibit blue to black hues depending on the degree of aggregation [

94,

95,

96]. AuNPs efficiently adsorb biomolecules to form recognition complexes, which is essential in aquaculture applications for water quality monitoring and disease detection [

97]. These nanoparticles are coated with bio-recognition materials, such as DNA, RNA, enzymes, or antibodies, which interact with target analytes, enabling detection through fluorescence, colorimetric, or electrochemical methods (

Figure 5).

AuNPs have shown promising results in disease diagnostics [

22,

98]. For example, a fiber-optic SPR biosensor was developed to detect nervous necrosis virus (NNV) early in infection by targeting viral coat proteins with AuNPs [

22]. Shrimps are sensitive to the pathogen white spot syndrome virus (WSSV), which is characterized by calcium deposition and lethargy. It is identified using AuNPs functionalized with anti-WSSV antibodies via self-assembled alkanethiol monolayers [

99]. Integrating AuNPs with optical sensing platforms, such as SPR biosensors, has significantly enhanced the sensitivity and specificity of aquatic disease diagnostics. These advances underline the critical role of SPR-based approaches in real-time monitoring of aquatic pathogens. Since the above methods provide quick results under extreme conditions, such as the rapid detection of viral disease outbreaks in fish, they enable for the adoption of timely and appropriate measures [

100,

101].

Figure 5.

Mechanism of working of the nanoparticle biosensor (modified after Hegde et al., [

102]. Curved arrow indicated antigens form the samples containing viral or bacterial infection while straight arrows indicate the forward steps.

Figure 5.

Mechanism of working of the nanoparticle biosensor (modified after Hegde et al., [

102]. Curved arrow indicated antigens form the samples containing viral or bacterial infection while straight arrows indicate the forward steps.

5.2.3. Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

The SPR biosensors are optical instruments that detect changes in refractive angles during specific analyte binding events [

103]. These sensors play a crucial role in aquaculture by detecting pathogens and toxins that are harmful to aquatic life. The Kretschmann configuration is the most widely used model that includes a dielectric-metal interface with a prism attached to a metal layer in an inverted position [

104]. When plane-polarized light exceeds the critical incident angle, total internal reflection occurs, and it transfers energy to excite surface electrons (typically on gold), producing surface plasmon waves. Noble metals such as gold, silver, platinum, and palladium enhance optical absorption properties [

105]. The plasmonic band, detected in the visible to near-infrared regions [

106], shifts with analyte binding and is monitored by changes in resonance angles. Finally, it provides a highly sensitive method for analyte detection [

107] (

Figure 6).

SPR technology is increasingly applied in aquaculture for water quality monitoring. Excess nitrogenous compounds from uneaten feed, fertilizer leaching, and fish waste can induce toxicity risks, particularly due to the ammonia load [

108]. An SPR biosensor using nitrate reductase from

Aspergillus niger and glutamine synthetase from

Escherichia coli on gold nanoparticles was developed to measure nitrate (NO

3−) and ammonium (NH

4+) concentrations, offering an effective tool for water analysis [

109]. Aquaculture intensification often degrades water quality, which leads to stress-related health issues in fish, and is influenced by factors such as pH, water flow, and temperature [

110]. Prolonged exposure to poor water conditions elevates cortisol, urea, and creatinine levels beyond normal physiological ranges [

111]. Addressing such issues, a polymer optical fiber coated with gold/platinum nanoparticles and anti-cortisol antibodies has been developed for direct cortisol monitoring in water bodies [

112], which is proposed to enhance fish health surveillance. Therefore, the use of SPR-based technology for detecting toxins, such as tetrodotoxin, in water bodies or for detecting diseases by measuring pathogen products, is recommended in aquaculture [

113]. In addition to water quality monitoring, biosensor innovations have expanded into pathogen detection, enabling early disease diagnosis in aquaculture systems. One such advancement involves cantilever-based biosensors, which offer remarkable sensitivity for detecting biological targets.

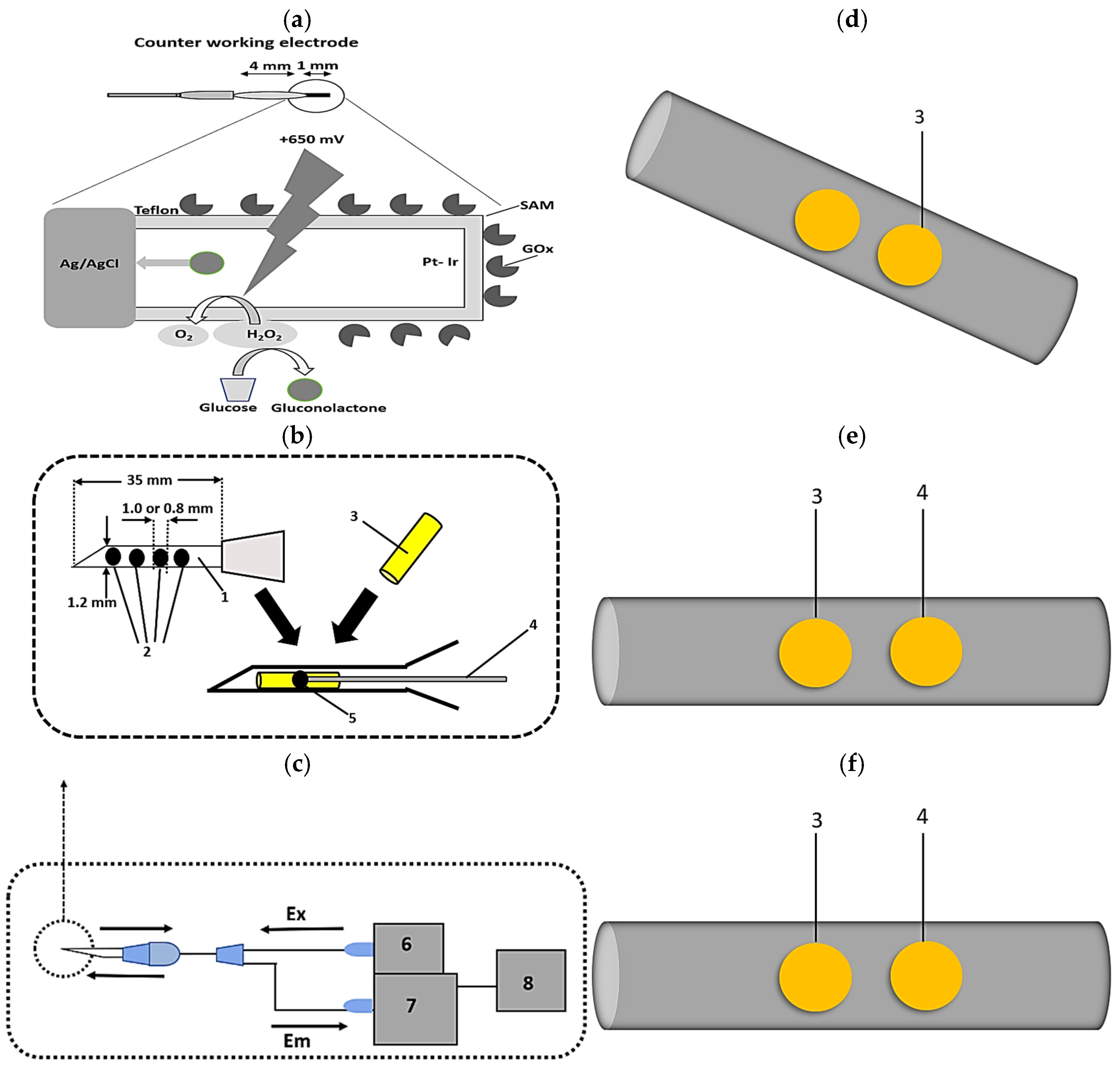

5.2.4. Microcantilever Biosensor

A cantilever is a structure fixed at one end and free at the other, similar to a diving board [

115]. Micro-cantilevers are a relatively recent innovation in aquaculture and have been utilized for disease detection in fish. It offers exceptional sensitivity and low detection limits, making it a valuable tool in aquaculture [

116]. These biosensors integrate microcantilevers with dynamic force microscopy (DFM) within an atomic force microscope (AFM), which detects shifts in resonance frequency upon binding of the target analyte [

117]. The piezoelectric actuator detects mass loading, resulting in a decrease in the resonance frequency [

118]. A study from Thailand demonstrated the first cantilever-based cholera detection, where a gold-coated microcantilever functionalized with antibodies specific to

Vibrio cholerae O1 showed a decrease in resonance frequency proportional to the bacterial concentration [

119].

Resonance frequency changes are measured via the optical beam deflection method, where a photodetector monitors a laser reflected from the cantilever, and the resulting photocurrents are processed through a data acquisition system [

120]. The differential displacement between a reference and measurement cantilever determines the presence and concentration of analytes, as evidenced by a bending signal that is lower than the base signal (

Figure 7). Overall, cantilever-based biosensors offer a promising approach for the early detection of waterborne pathogens, which helps to prevent disease outbreaks in aquaculture farms and artisanal fish farming. Despite their advantages, cantilever sensors can be limited by environmental disturbances, highlighting the need for alternative high-sensitivity detection platforms. Consequently, other biosensing technologies have been explored to further enhance diagnostic accuracy. Undoubtedly, ultrasensitive and rapid detection systems in microcantilever biosensors expand their diverse application fields, including aquaculture, to reduce the risk of contamination, particularly during disease outbreaks. Detection of

V. cholerae in water samples using DFM is a notable example in the aquaculture industry [

119]. Detection of the bacterium

Escherichia coli using a V-shaped microcantilever sensor from water samples is another example [

121]. Similarly, the detection of a 1 pg/mL level of okadaic acid is also achieved using an aptamer-based microcantilever-array biosensor. The measurement of glucose levels in bio-samples using an integration of glucose aptamer, glucose oxidase, and horseradish peroxidase enzymes with the substrate 2,2′-biazobis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) is also noted at a sensitivity level of 0.013 mM [

122].

5.2.5. Quartz Crystal Microbalance Biosensor

Traditional detection methods, such as microscopy, ELISA, and PCR, are often tedious, time-consuming, and prone to yielding false positive results in samples. Consequently, the development of biosensors has provided a more sensitive, efficient, and point-of-care alternative for analyte detection [

123]. Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) biosensors offer a low detection limit and high specificity that minimizes false positive results on one hand and limits the risk of biosensor damage on the other [

124,

125]. The QCM operates on the principle of piezoelectricity. It utilizes gold-coated quartz electrodes to detect changes in mass through shifts in resonance frequency, which facilitates analyte recognition [

126]. The QCM with Dissipation Monitoring (QCM-D) system is an advancement of this technology. It measures both frequency changes and energy dissipation during analyte binding and removal, thereby enhancing analytical capabilities [

127].

In QCM-D, a specific recognition material is immobilized on the quartz surface to selectively bind target analytes. It causes a mass increase coupled with a decrease in frequency. To further enhance the detection limit, nanoparticles can be attached to secondary antibodies without modification [

128] or used directly to increase the detectable mass [

129,

130]. This multi-phase detection mechanism comprises initial antibody immobilization (highest frequency), analyte binding (reduced frequency), secondary antibody–nanoparticle conjugation (further decrease in frequency), and regeneration upon removal of bound entities (

Figure 8). However, coatings of antibodies and nucleic acids are prone to denaturation when exposed to environmental fluctuations, which limits their stability. To overcome this issue, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) have been introduced as synthetic alternatives to biological recognition elements. MIPs provide enhanced stability against pH, temperature, and ionic changes, which help maintain the integrity of the QCM-D biosensing system [

131]. While QCM-D leverages mechanical responses to detect biomolecular interactions, electrochemical biosensors translate biochemical events into electrical signals, which offer complementary approaches for sensitive detection. These platforms continue to evolve by incorporating innovative materials and transduction strategies that broaden their applications in diagnostics and environmental monitoring. The detection of

Vibrio harveyi bacterial pathogens in shrimp farms [

132] and

Aeromonas hydrophila bacterial pathogens in fish farms using QCM has already been documented.

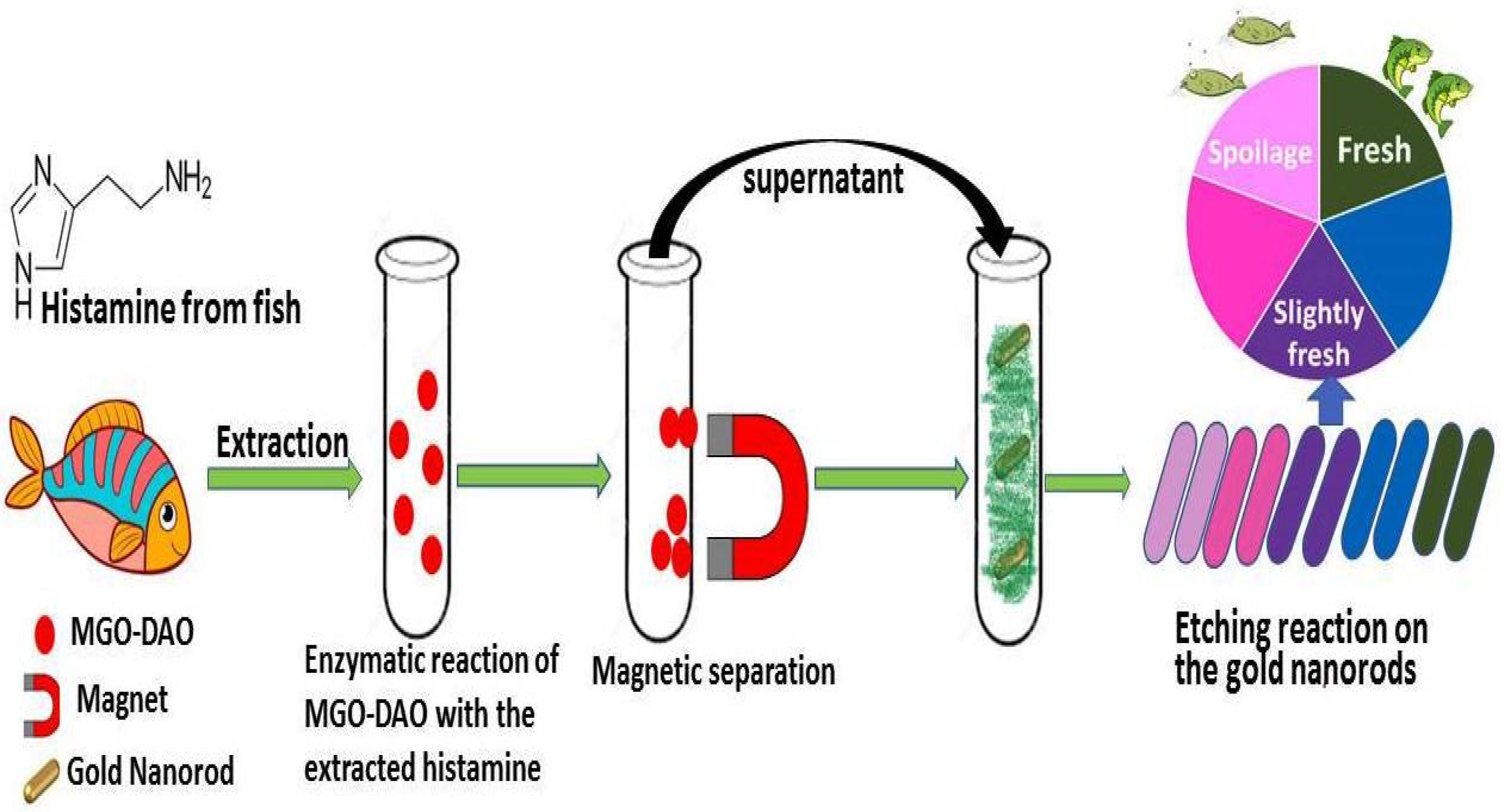

5.2.6. Electrochemical Biosensor

Electrochemical biosensors incorporate biological compounds such as nucleic acids, antibodies, and enzymes, coupled with various types of transducers that define the specific biosensor category (

Table 3). They offer high specificity, robustness, ultra-high sensitivity, low detection limits, and suitability for point-of-care diagnostics [

134]. For example, potentiometric biosensors measure the potential difference between a working and a reference electrode. The biorecognition material coated on the working electrode facilitates the selective detection of the analyte compared to the reference [

135]. Similarly, amperometric biosensors detect current changes in response to an applied potential. Its surface is coated with a redox-active analyte that undergoes oxidation or reduction, and the resulting electric current, which is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte, is measured [

136]. Conductometric biosensors monitor variations in electrical conductivity arising from the interaction between the biorecognition element and the target analyte [

137]. Together, these approaches demonstrate the versatility and effectiveness of electrochemical reactions in biosensing applications [

138]. For example, applications of electrochemical biosensors have been noted to detect NH

4+ at a concentration of 0.65 μM using nanoparticle/polymethylene [

139], and the measurement of xanthine with 97% accuracy, at a concentration of 47.96 nM, serving as an indicator of spoilage in stored fish, even after 30 days [

140]. Therefore, the application of biosensors in aquaculture, specifically in fish farms, can enhance productivity by mitigating the associated on-field problems.

In summary, biosensors have the potential to mitigate several risks in the aquaculture sector, ranging from early, rapid, and real-time detection to auto-predicting solutions when integrated with AI- or IoT-based tools. They can be used for routine analysis at a cost-effective rate. Optical sensors can also be used for early, quick, and real-time monitoring of aquaculture systems with high precision in a non-invasive mode. While QCM biosensors offer superior mass sensitivity for detecting pathogen loads at the molecular level, they can be costly. Therefore, the choice to use specific biosensors can depend on the requirements (

Table 3).

7. Conclusions and Prospective

The pressing global challenges of food security and malnutrition necessitate a significant increase in fish farming, surpassing the currently observed rate. Detection and management of the difficulties observed in fish farms would be beneficial in achieving the above goal in a sustainable manner. Sensor-based technology is used to detect such challenges, including environmental changes, disease detection and outbreak, growth assessment, production efficiency, and reproductive success. The application of contemporary technology, including biosensors, throughout various phases of fish culture has proven beneficial in addressing numerous prevalent challenges in the field. The potential to revolutionize the fishery industry by implementing biosensor technology represents a crucial advancement in addressing its various challenges. Despite the advancement of biosensor technology in aquaculture farms, the commercialization of multiple techniques and tools is still under investigation. The commercialization and production of miniatures of such techniques at a micro-level such as for brood stock management, need to be achieved. Most portable devices require integration with automated AI-based algorithms to provide a need-based interface control system for farmers. Remote management of aquaculture challenges, utilizing biosensors, remains to be addressed with AI- and IoT-based tools. A broad focus needs to be given to the development of such biosensors for both artisanal and large-scale fish farming sectors.