Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Corn Oil Based on the Phenolic Compounds Profile Obtained by UHPLC-MS/MS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Solvents and Analytical Standards

2.2. Oil Samples

2.3. Extraction of Polar Fraction of Oil Samples

2.4. UHPLC-HRMS Analysis of Phenolic Compounds in Oil Samples

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Vegetable Oils by UHPLC-HRMS

3.2. Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Vegetable Oils

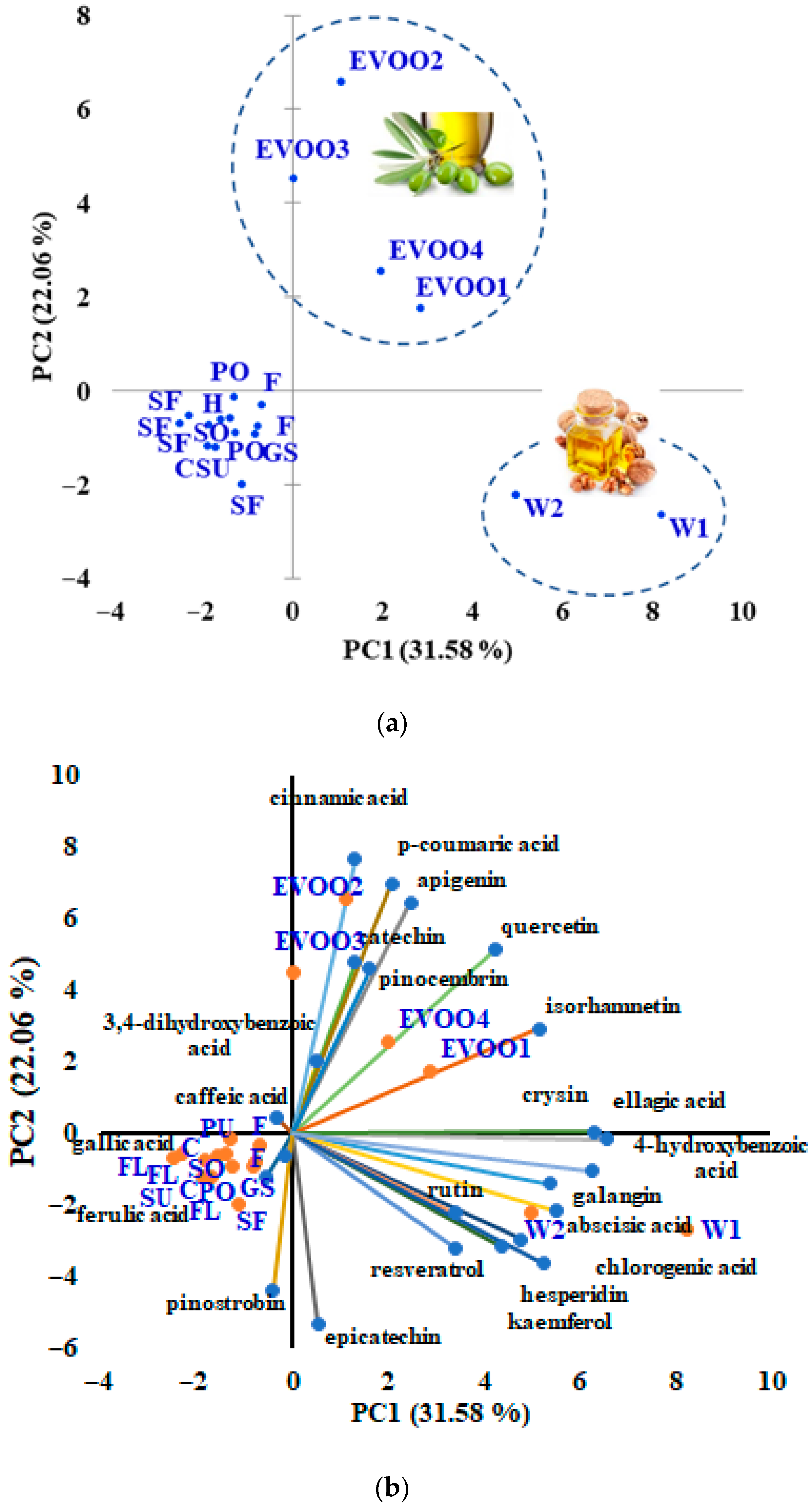

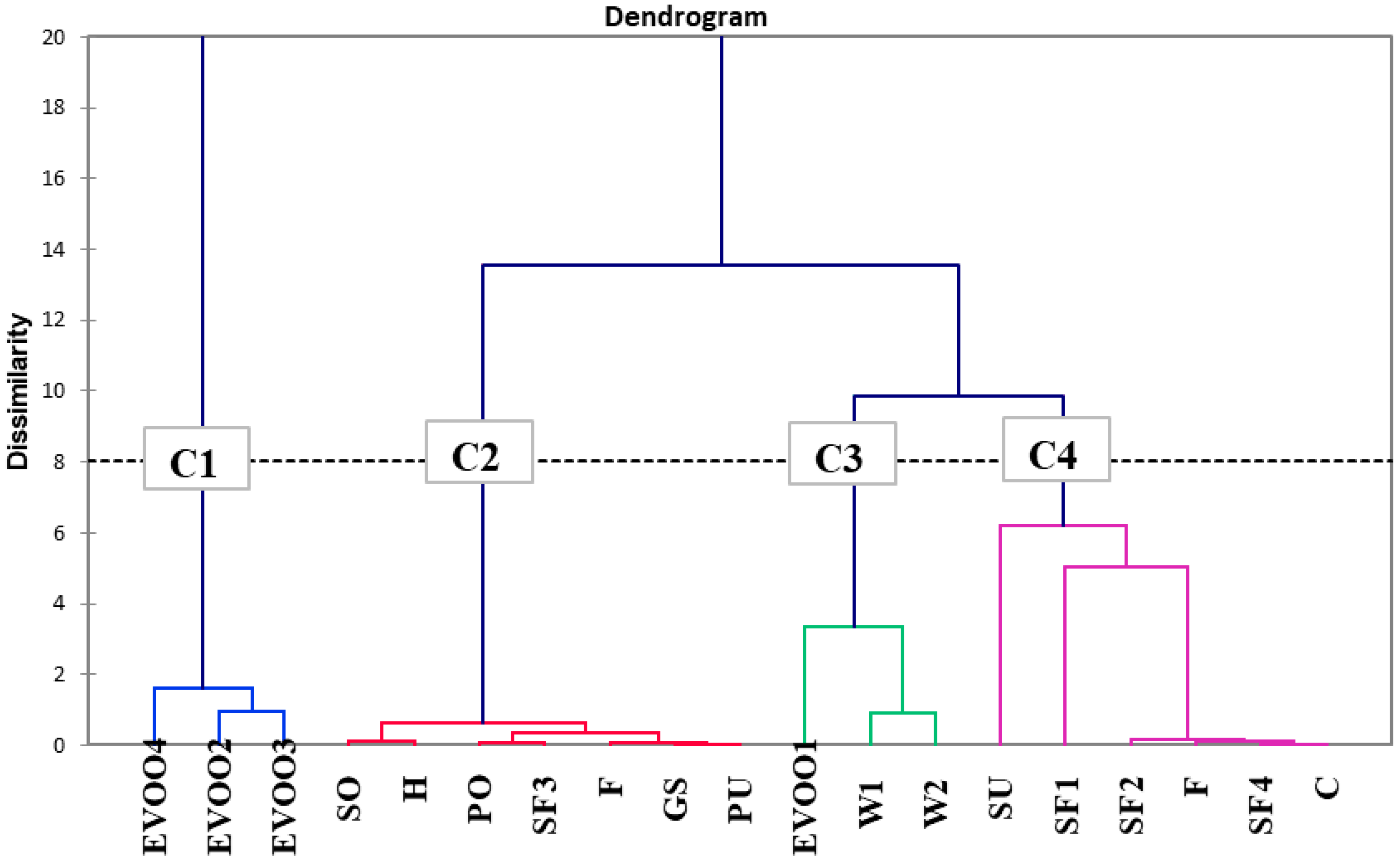

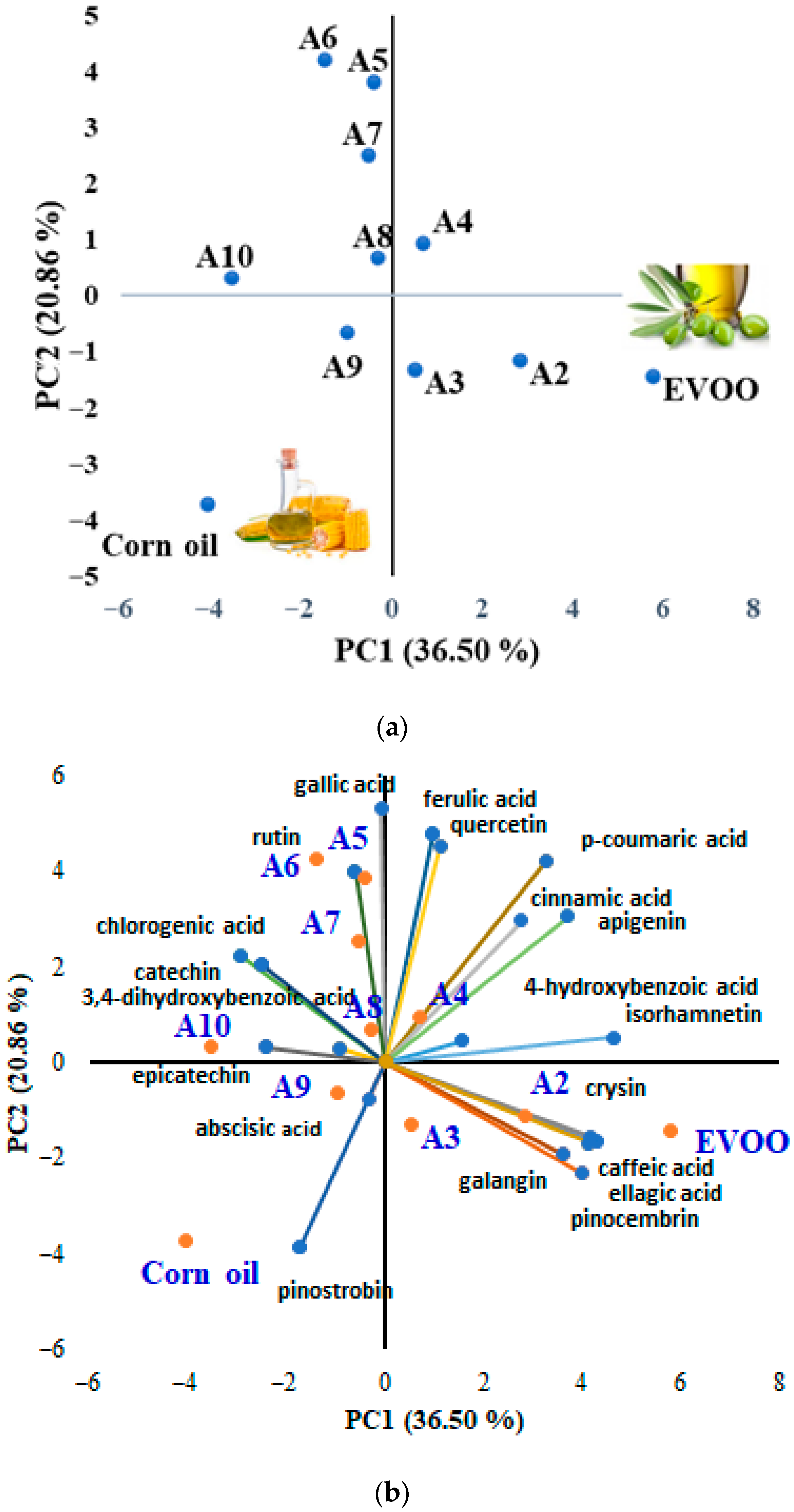

3.3. Discrimination of Vegetable Oils Based on Targeted and Untargeted HRMS Analysis of Phenolic Compounds

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zio, S.; Tarnagda, B.; Sankara, S.; Tapsoba, F.; Zongo, C.; Savadogo, A. Nutritional and Therapeutic Interest of Most Widely Produced and Consumed Plant Oils by Human: A Review. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashempour-Baltork, F.; Vali Zade, S.; Mazaheri, Y.; Mirza Alizadeh, A.; Rastegar, H.; Abdian, Z.; Torbati, M.; Azadmard Damirchi, S. Recent Methods in Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration: State-of-the-Art. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Sacanella, E.; Tahiri, I.; Casas, R. Mediterranean Diet and Role of Olive Oil. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 205–214. ISBN 978-0-12-819528-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Carretero, A.; Menéndez-Menéndez, J.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Polyphenols in Olive Oil. In Olives and Olive Oil in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 167–175. ISBN 978-0-12-374420-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovska Petkoska, A.; Trajkovska-Broach, A. Health Benefits of Extra Virgin Olive Oil. In Olive Oil—New Perspectives and Applications; Akram, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; ISBN 978-1-83968-414-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritsakis, A. Extra Virgin Olive Oil Composition and Its Bioactive Phenolic Compounds. Nov. Tech. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 654–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.C.; Mszar, R.; Ostfeld, R.J.; Ferrucci, L.M.; Mucci, L.A.; Giovannucci, E.; Loeb, S. Diet and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. CardioOnc. 2025, 7, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, G. Polyphenols: Potent Protectors against Chronic Diseases. Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorzynik-Debicka, M.; Przychodzen, P.; Cappello, F.; Kuban-Jankowska, A.; Marino Gammazza, A.; Knap, N.; Wozniak, M.; Gorska-Ponikowska, M. Potential Health Benefits of Olive Oil and Plant Polyphenols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedan, V.; Popp, M.; Rohn, S.; Nyfeler, M.; Bongartz, A. Characterization of Phenolic Compounds and Their Contribution to Sensory Properties of Olive Oil. Molecules 2019, 24, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inarejos-García, A.M.; Santacatterina, M.; Salvador, M.D.; Fregapane, G.; Gómez-Alonso, S. PDO Virgin Olive Oil Quality—Minor Components and Organoleptic Evaluation. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 2138–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montaña, E.J.; Brignot, H.; Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; Thomas-Danguin, T.; Morales, M.T. Phenols and Saliva Effect on Virgin Olive Oil Aroma Release: A Chemical and Sensory Approach. Food Chem. 2024, 437, 137855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caponio, F.; Gomes, T.; Pasqualone, A. Phenolic Compounds in Virgin Olive Oils: Influence of the Degree of Olive Ripeness on Organoleptic Characteristics and Shelf-Life. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 212, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.S.; Schmiele, M. From Olive to Olive Oil: A General Approach. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e32210313408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, F.; Ceccarini, M.R.; Bistarelli, S.; Galli, F.; Cossignani, L.; Bartolini, D.; Ianni, F. Impact of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Storage Conditions on Phenolic Content and Wound-Healing Properties. Foods 2025, 14, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, M.L.; Becerra, M.; Sayago, A.; Beltrán, M.; Beltrán, R. Comparison of Different Extraction Methods to Determine Phenolic Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil. Food Anal. Methods 2013, 6, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncirik, K.; Fritsche, S. Comparability and Reliability of Different Techniques for the Determination of Phenolic Compounds in Virgin Olive Oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2004, 106, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geana, E.-I.; Ciucure, C.T.; Apetrei, I.M.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Apetrei, C. Discrimination of Olive Oil and Extra-Virgin Olive Oil from Other Vegetable Oils by Targeted and Untargeted HRMS Profiling of Phenolic and Triterpenic Compounds Combined with Chemometrics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, F.; Wang, W. Profiling of Phenolic Compounds in Domestic and Imported Extra Virgin Olive Oils in China by High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Electrochemical Detection. LWT 2023, 174, 114424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounegru, A.V.; Apetrei, C. Evaluation of Olive Oil Quality with Electrochemical Sensors and Biosensors: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagözlü, M.; Adun, P.; Ozsoz, M.; Aşır, S. Detection of Adulteration in Cold-pressed Olive Oil by Voltammetric Analysis of Alpha-tocopherol on Single-use Pencil Graphite Electrode. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 1781–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.H.; Hussain, R.O.; Shaheed, D.S.; AbuKhader, M.; Khan, S.A. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis and in Vitro Biological Studies on Fixed Oil Isolated from the Waste Pits of Two Varieties of Olea europaea L. Oilseeds Crops Lipids 2019, 26, 28. Oilseeds Crops Lipids 2019, 26, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caño-Carrillo, I.; Gilbert-López, B.; Ruiz-Samblás, C.; Molina-Díaz, A.; García-Reyes, J.F. Virgin Olive Oil Authenticity Assays in a Single Run Using Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 17319–17328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, X.; N’Diaye, K.; Harkaoui, S.E.; Willenberg, I.; Ma, F.; Zhang, L.; Li, P.; Matthäus, B. Authentication of Virgin Olive Oil Based on Untargeted Metabolomics and Chemical Markers. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2025, 127, e202400126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, G.; Lorenzo, J.M. Plant Source: Vegetable Oils. In Food Lipids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 69–85. ISBN 978-0-12-823371-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailer, R.J. Authenticity and quality of extra virgin olive oil: Future directions for analytical techniques. Acta Hortic. 2014, 1057, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abamba Omwange, K.; Al Riza, D.F.; Saito, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Ogawa, Y.; Shiraga, K.; Giametta, F.; Kondo, N. Potential of Front Face Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Fluorescence Imaging in Discriminating Adulterated Extra-Virgin Olive Oil with Virgin Olive Oil. Food Control 2021, 124, 107906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaroual, H.; El Hadrami, E.M.; Farah, A.; Ez Zoubi, Y.; Chénè, C.; Karoui, R. Detection and Quantification of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration by Other Grades of Olive Oil Using Front-Face Fluorescence Spectroscopy and Different Multivariate Analysis Techniques. Food Chem. 2025, 479, 143736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Castellón, J.; López-Yerena, A.; Domínguez-López, I.; Siscart-Serra, A.; Fraga, N.; Sámano, S.; López-Sabater, C.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Pérez, M. Extra Virgin Olive Oil: A Comprehensive Review of Efforts to Ensure Its Authenticity, Traceability, and Safety. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe 2022, 21, 2639–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanou, E.; Bekogianni, M.; Stamatoukos, T.; Couris, S. Detection of Adulteration of Extra Virgin Olive Oil via Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy and Ultraviolet-Visible-Near-Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy: A Comparative Study. Foods 2025, 14, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadei, E.; Valli, E.; Panni, F.; Donarski, J.; Farrús Gubern, J.; Lucci, P.; Conte, L.; Lacoste, F.; Maquet, A.; Brereton, P.; et al. Emerging Trends in Olive Oil Fraud and Possible Countermeasures. Food Control 2021, 124, 107902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, W.; Kuo, C.; Hsu, Y.; Lai, C. Determination of Adulteration, Geographical Origins, and Species of Food by Mass Spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, 42, 2273–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajoub, A.; Medina-Rodríguez, S.; Gómez-Romero, M.; Ajal, E.A.; Bagur-González, M.G.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A.; Carrasco-Pancorbo, A. Assessing the Varietal Origin of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Using Liquid Chromatography Fingerprints of Phenolic Compound, Data Fusion and Chemometrics. Food Chem. 2017, 215, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Ferro, M.D.; Cavaco, I.; Liang, Y. Detection and Identification of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration by GC-MS Combined with Chemometrics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3693–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Torre-Carbot, K.; Jauregui, O.; Gimeno, E.; Castellote, A.I.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; López-Sabater, M.C. Characterization and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds in Olive Oils by Solid-Phase Extraction, HPLC-DAD, and HPLC-MS/MS. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 4331–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Beltrán, C.H.; Jiménez-Carvelo, A.M.; Martín-Torres, S.; Ortega-Gavilán, F.; Cuadros-Rodríguez, L. Instrument-Agnostic Multivariate Models from Normal Phase Liquid Chromatographic Fingerprinting. A Case Study: Authentication Olive Oil. Food Control 2022, 137, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Morabit, Y.; El Maadoudi, M.; Alahlah, N.; Salhi, A.; Elyoussfi, A.; Amhamdi, H.; Ahari, M. Charting a Decade of Olive Oil Authentication: A Bibliometric Survey of Spectroscopy and Chemometrics (2014–2024). Microchem. J. 2025, 216, 114493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouri, E.; Revelou, P.-K.; Kanakis, C.; Daferera, D.; Pappas, C.S.; Tarantilis, P.A. Authentication of the Botanical and Geographical Origin and Detection of Adulteration of Olive Oil Using Gas Chromatography, Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy Techniques: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malavi, D.; Raes, K.; Van Haute, S. Integrating Near-Infrared Hyperspectral Imaging with Machine Learning and Feature Selection: Detecting Adulteration of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil with Lower-Grade Olive Oils and Hazelnut Oil. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2024, 9, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apetrei, I.M.; Apetrei, C. Detection of Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration Using a Voltammetric E-Tongue. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 108, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlak, İ.H.; Milli, M.; Milli, N.S. Machine Learning–Based Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration Using BME688 Gas Sensor Matrix. Food Anal. Methods 2025, 18, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, N.; Marx, Í.M.G.; Casal, S.; Dias, L.G.; Veloso, A.C.A.; Pereira, J.A.; Peres, A.M. Application of an Electronic Tongue as a Single-Run Tool for Olive Oils’ Physicochemical and Sensory Simultaneous Assessment. Talanta 2019, 197, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamara, M.R.; Hafifah, C.N.; Julian, T.; Lelono, D.; Roto, R.; Triyana, K. Development of Potentiometric Electronic Tongue to Identify Adulteration of Olive Pomace Oil in Extra Virgin Olive Oil. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Theoretical and Applied Physics: The Spirit of Research and Collaboration Facing the COVID-19 Pandemic, Surabaya, Indonesia, 27–28 October 2021; p. 040005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonetti, F.; Martelli, F.; Resta, G. Artificial Neural Networks Applied to Olive Oil Production and Characterization: A Systematic Review. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2025, 26, 200525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonico, M.; Grasso, S.; Genova, F.; Zompanti, A.; Parente, F.; Pennazza, G. Unmasking of Olive Oil Adulteration Via a Multi-Sensor Platform. Sensors 2015, 15, 21660–21672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R.; Díaz, F.; Melo, L. Portable MOS Electronic Nose Screening of Virgin Olive Oils with HS-SPME-GC–MS Corroboration: Classification and Estimation of Sunflower-Oil Adulteration. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, H.; Kahfi, J.; Dutta, A.; Jaremko, M.; Emwas, A.-H. The Detection of Adulteration of Olive Oil with Various Vegetable Oils—A Case Study Using High-Resolution 700 MHz NMR Spectroscopy Coupled with Multivariate Data Analysis. Food Control 2024, 166, 110679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraipandian, S.; Petersen, J.C.; Lassen, M. Authenticity and Concentration Analysis of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Using Spontaneous Raman Spectroscopy and Multivariate Data Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.C.; Liong, C.-Y.; Jemain, A.A. Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) for Classification of High-Dimensional (HD) Data: A Review of Contemporary Practice Strategies and Knowledge Gaps. Analyst 2018, 143, 3526–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, H.S.; Li, X.; De Pra, M.; Lovejoy, K.S.; Steiner, F.; Acworth, I.N.; Wang, S.C. A Rapid Method for the Detection of Extra Virgin Olive Oil Adulteration Using UHPLC-CAD Profiling of Triacylglycerols and PCA. Food Control 2020, 107, 106773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Gao, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L. Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Vegetable Oils by Ultra-performance Convergence Chromatography-quadrupole Time-of-flight Mass Spectrometry (UPC2-QTOF MS) Coupled with Multivariate Data Analysis Based on the Differences of Triacylglycerol Compositions. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3759–3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Yang, D.; Mao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, L.; Yang, X.; Li, P. Accurate Quantification of TAGs to Identify Adulteration of Edible Oils by Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Quadrupole-Time of Flight-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carranco, N.; Farrés-Cebrián, M.; Saurina, J.; Núñez, O. Authentication and Quantitation of Fraud in Extra Virgin Olive Oils Based on HPLC-UV Fingerprinting and Multivariate Calibration. Foods 2018, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | C (g) | EVOO (g) | c% |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVOO | 0 | 20 | 0 |

| A2 | 0.1 | 19.9 | 0.5 |

| A3 | 0.2 | 19.8 | 1 |

| A4 | 0.5 | 19.5 | 2.5 |

| A5 | 0.6 | 19.4 | 3 |

| A6 | 1 | 19 | 5 |

| A7 | 1.5 | 18.5 | 7.5 |

| A8 | 2 | 18 | 10 |

| A9 | 3.9 | 16 | 19.5 |

| A10 | 10 | 10 | 50 |

| C | 20 | 0 | 100 |

| # | Compound | Retention Time [min] | m/z [M − H]− | Mass Fragments | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Acids | |||||

| 1 | Gallic acid | 0.68 | 169.0133 | 125.0231 | 0.9837 |

| 2 | 3,4-dihidroxibenzoic acid | 1.59 | 153.0183 | 109.0281 | 0.9991 |

| 3 | p-hydroxybenzoic acid | 5.40 | 137.0232 | 93.0331 | 0.9996 |

| 4 | Chlorogenic acid | 7.55 | 353.0879 | 191.0553 | 0.9945 |

| 5 | Syringic acid | 8.03 | 197.0450 | 182.0212, 166.9976, 153.0547, 138.0311, 123.0075 | 0.9872 |

| 6 | Caffeic acid | 8.08 | 179.0338 | 135.044 | 0.9986 |

| 7 | p-coumaric acid | 8.59 | 163.0392 | 119.0489 | 0.9976 |

| 8 | Ferulic acid | 8.83 | 193.0500 | 178.0262, 134.0361 | 0.9989 |

| 9 | Ellagic acid | 9.66 | 300.9990 | 300.9990 | 0.9796 |

| 10 | Cinnamic acid | 10.45 | 147.0441 | 119.0489, 103.0387 | 0.9951 |

| 11 | Abscisic acid | 10.04 | 263.1288 | 179.9803, 191.9454 | 0.9995 |

| Flavonoids | |||||

| 12 | (+)-catechin | 7.57 | 289.0719 | 109.0282, 125.0232, 137.0232, 151.0390, 203.0708, 245.0817 | 0.9963 |

| 13 | (-)-epicatechin | 8.05 | 289.0719 | 109.0282, 125.0232, 137.0232, 151.0390, 203.0708, 245.0817 | 0.9949 |

| 14 | Quercetin | 10.74 | 301.0356 | 151.0226, 178.9977, 121.0282, 107.0125 | 0.9188 |

| 15 | Naringin | 9.25 | 579.1718 | 363.0721 | 0.9997 |

| 16 | Hesperidin | 9.37 | 609.1824 | 377.0876 | 0.9988 |

| 17 | Rutin | 9.43 | 609.1462 | 3345.0614 | 0.9965 |

| 18 | Kaempferol | 11.62 | 285.0406 | 151.0389, 117.0180 | 0.9916 |

| 19 | Isorhamnetin | 11.80 | 315.0512 | 300.0276 | 0.9637 |

| 20 | Apigenin | 11.86 | 269.0457 | 117.0333, 151.0027, 107.0126 | 0.9977 |

| 21 | Pinocembrin | 12.70 | 255.0663 | 213.0551, 151.0026, 107.0125 | 0.9897 |

| 22 | Chrysin | 13.52 | 253.0506 | 143.0491, 145.0284, 107.0125, 209.0603, 63.0226, 65.0019 | 0.9999 |

| 23 | Galangin | 13.77 | 269.0458 | 169.0650, 143.0491 | 0.9889 |

| 24 | Pinostrobin | 14.84 | 269.081 | 179.0554 | 0.9833 |

| Stilbenes | |||||

| 25 | t-Resveratrol | 9.55 | 227.0707 | 185.0813, 143.0337 | 0.9988 |

| Model | Analyzed Sample | Correctly Classified Samples/% | Misclassified Samples/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genuine EVOO/Adulterated EVOO | EVOO1 | 100 | 0 |

| EVOO2 | 100 | 0 | |

| EVOO3 | 100 | 0 | |

| EVOO4 | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 0.5% | 83.333 | 16.667 | |

| C/EVOO1 1% | 92.361 | 7.639 | |

| C/EVOO1 2.5% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 3% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 5% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 7.5% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 10% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 19.5% | 100 | 0 | |

| C/EVOO1 50% | 100 | 0 | |

| C | 100 | 0 | |

| W | 100 | 0 | |

| GS | 100 | 0 | |

| PU | 100 | 0 | |

| F | 100 | 0 | |

| SO | 100 | 0 | |

| SE | 100 | 0 | |

| H | 100 | 0 | |

| PO | 100 | 0 | |

| SF | 100 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geana, E.-I.; Apetrei, I.M.; Apetrei, C. Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Corn Oil Based on the Phenolic Compounds Profile Obtained by UHPLC-MS/MS. Chemosensors 2025, 13, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120408

Geana E-I, Apetrei IM, Apetrei C. Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Corn Oil Based on the Phenolic Compounds Profile Obtained by UHPLC-MS/MS. Chemosensors. 2025; 13(12):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120408

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeana, Elisabeta-Irina, Irina Mirela Apetrei, and Constantin Apetrei. 2025. "Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Corn Oil Based on the Phenolic Compounds Profile Obtained by UHPLC-MS/MS" Chemosensors 13, no. 12: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120408

APA StyleGeana, E.-I., Apetrei, I. M., & Apetrei, C. (2025). Detection of Olive Oil Adulteration with Corn Oil Based on the Phenolic Compounds Profile Obtained by UHPLC-MS/MS. Chemosensors, 13(12), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/chemosensors13120408