Nurse’s Role from Medical Students’ Perspective during Their Interprofessional Clinical Practice: Evidence from Lithuania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

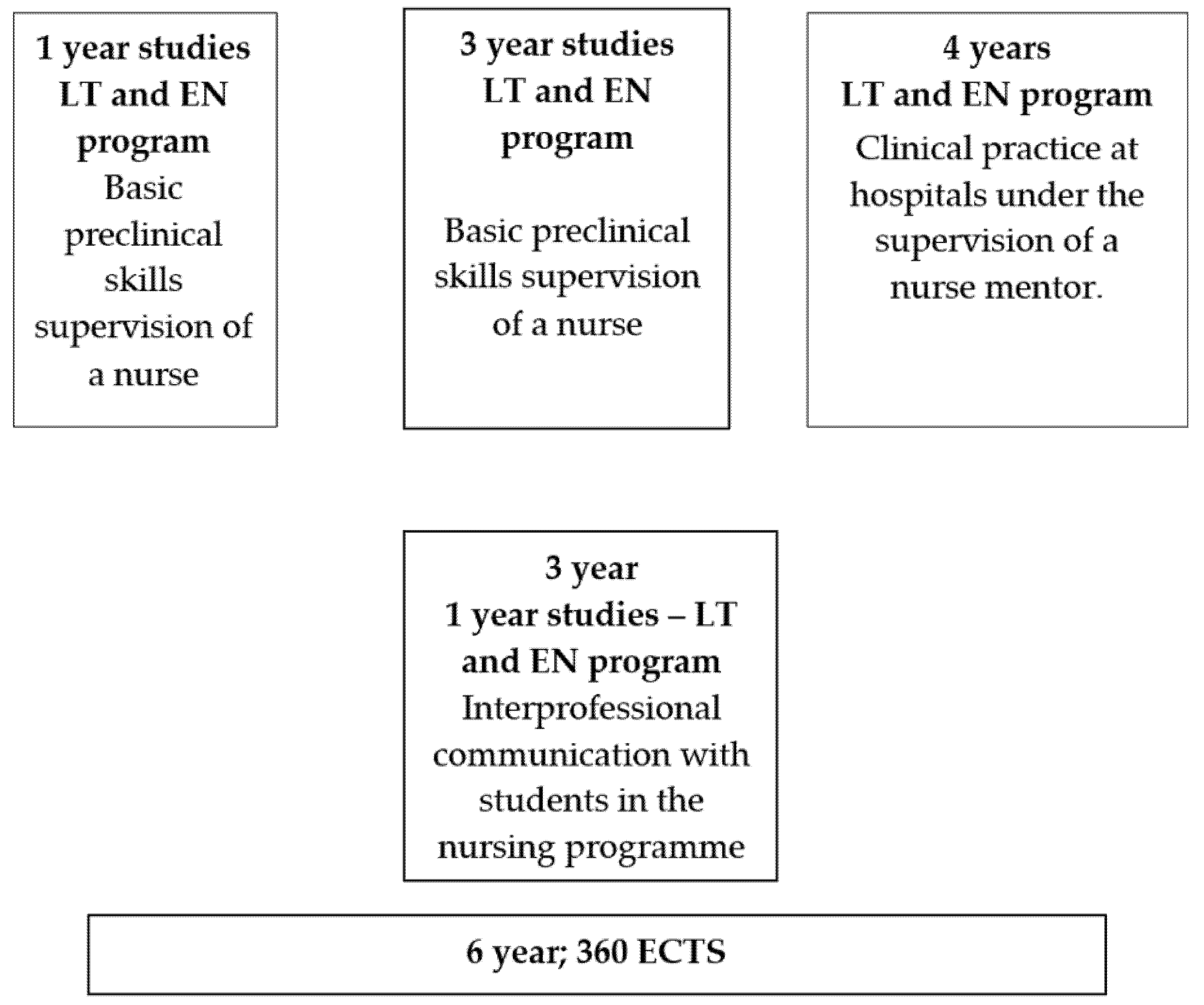

2.2. Medical Programme Description

2.3. Participants

2.4. Settings

2.5. Questionnaire Instrument

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Medical Students’ Attitudes of the Nurse’s Role

4. Discussion

4.1. Breadth of Professional Outlook

4.2. Professional Image of Nurse and Professional Interdependence

5. Conclusions

5.1. Implication for Education and Practice

5.2. List of Abbreviations

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reeves, S.; Pelone, F.; Harrison, R.; Goldman, J.; Zwarenstein, M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, CD000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg-Martinell, A.; Hult, H.; Henriksson, P.; Kiessling, A. Possibilities for interprofessional learning at a Swedish acute healthcare ward not dedicated to interprofessional education: An ethnographic study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, H.G.J.; Teunissen, P.W.; Favier, R.P.; Rietbroek, N.J.; Theyse, L.F.; Brommer, H.; Haarhuis, J.C.; Van Beukelen, P.; Van Der Vleuten, C.P.; Jaarsma, D.A. Programmatic assessment of competency-based workplace learning: When theory meets practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.K.; Rivera, J.; Rotter, N.; Green, E.; Kools, S. Interprofessional education in the clinical setting: A qualitative look at the preceptor’s perspective in training advanced practice nursing students. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 21, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, N.; Salmon, N.; Clifford, A.M. ‘It benefits patient care’: The value of practice-based IPE in healthcare curriculums. BMC Med Educ. 2020, 20, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, M.; Senior, E. The experiences of students in interprofessional learning. Br. J. Nurs. 2017, 26, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peduzzi, M.; Aguiar, C.; Lima, A.M.; Montanari, P.M.; Leonello, V.M.; Oliveira, M.R. Expansion of the interprofessional clinical practice of Primary Care nurses. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2019, 72 (Suppl. 1), 114–121, (In English and Portuguese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, K.; Rajupadhya, R.; Gongal, R.; Manca, T.; Ross, S.; Nichols, D. A clinical nursing rotation transforms medical students’ interprofessional attitudes. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0197161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mickan, S.M. Evaluating the effectiveness of health care teams. Aust. Health Rev. 2005, 29, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raurell-Torreda, M.; Rascon-Hernan, C.; Malagon-Aguilera, C.; Bonmatí-Tomas, A.; Bosch-Farre, C.; Gelabert-Vilella, S.; Romero-Collado, A. Effectiveness of a training intervention to improve communication between/awareness of team roles: A randomized clinical trial. J. Prof. Nurs. 2021, 37, 479–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadolski, G.J.; Bell, M.A.; Brewer, B.B.; Frankel, R.M.; Cushing, H.E.; Brokaw, J.J. Evaluating the quality of interaction between medical students and nurses in a large teaching hospital. BMC Med. Educ. 2006, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.B.; Miner, D.C.; Rivlin, L. ‘It depends’: Medical residents’ perspectives on working with nurses. Am. J. Nurs. 2009, 109, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, S.; Boet, S.; Zierler, B.; Kitto, S. Interprofessional Education and Practice Guide No.3: Evaluating interprofessional education. J. Interprof. Care 2015, 29, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treston, C. COVID-19 in the Year of the Nurse. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2020, 31, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, S. The role perception questionnaire (RPQ): A tool for assessing undergraduate students’ perceptions of the role of other professions. J. Interprof. Care 2004, 18, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, V.M.; Schocksnider, J. Leaders: Are you ready for change? The clinical nurse as care coordinator in the new health care system. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2014, 38, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Valizadeh, L.; Khajehgoodar, M. Assessment of nurse–patient communication and patient satisfaction from nursing care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeghebo, L. The image of nursing as perceived by nurses. Nurse Educ. Today 2012, 32, e49–e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oandasan, R.; Baker, K.; Barker, C.; Bosco, D.; D’Amour, L.; Jones, S.; Kimpton, S.; Lemieux-Charles, L.; Nasmith, L.; Rodriguez, L.S.M.; et al. Teamwork in Health Care: Promoting Effective Teamwork in Health Care in Canada: Policy Synthesis and Recommendations; Canadian Health Services Research Foundation: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Homeyer, S.; Hoffmann, W.; Hingst, P.; Oppermann, R.F.; Dreier-Wolfgramm, A. Effects of interprofessional education for medical and nursing students: Enablers, barriers and expectations for optimizing future interprofessional collaboration—A qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2018, 17, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aase, I.; Hansen, B.S.; Aase, K. Norwegian nursing and medical students’ perception of interprofessional teamwork: A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2014, 14, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, C.L.F.; Ket, J.C.F.; Croiset, G.; Kusurkar, R.A. Perceptions of residents, medical and nursing students about Interprofessional education: A systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative literature. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varpio, L.; Bidlake, E.; Casimiro, L.; Hall, P.; Kuziemsky, C.; Brajtman, S.; Humphrey-Murto, S. Resident experiences of informal education: How often, from whom, about what and how. Med. Educ. 2014, 48, 1220–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doja, A.; Venegas, L.C.; Clarkin, C.; Scowcroft, K.; Ashton, G.; Hopkins, L.; Bould, M.D.; Writer, H.; Posner, G. Varying perceptions of the role of “nurse as teacher” for medical trainees: A qualitative study. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2021, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mthiyane, G.N.; Habedi, D.S. The experiences of nurse educators in implementing evidence-based practice in teaching and learning. Health SA Gesondheid. 2018, 23, a1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaman, K.; Saunders, R.; Dugmore, H.; Tobin, C.; Singer, R.; Lake, F. Shifts in nursing and medical students’ attitudes, beliefs and behaviours about interprofessional work: An interprofessional placement in ambulatory care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3123–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burford, B.; Greig, P.; Kelleher, M.; Merriman, C.; Platt, A.; Richards, E.; Davidson, N.; Vance, G. Effects of a single interprofessional simulation session on medical and nursing students’ attitudes toward interprofessional learning and professional identity: A questionnaire study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, C.; Smith, L.; Bradshaw, M.; Hardcastle, W. Facilitating interprofessional learning for medical and nursing students in clinical practice. Learn. Health Soc. Care 2002, 1, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, M.M.; Aiken, M.R. Supporting Effective Collaboration: Using a Rearview Mirror to Look Forward. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2016, 26, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stepney, P.; Callwood, I.; Ning, F.; Downing, K. Learning to collaborate: A study of nursing students’ experience of inter-professional education at one UK university. Educ. Stud. 2011, 37, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Mean Score | LT | EN | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Lower Quartile, Upper Median Quartile | |||||

| 1 | Role is clear and transparent to other professionals vs. Uncertainty among other professionals about what the role involves | 2.98 | 2 (1–4) | 4 (2–6) | <0.001 |

| 2 | Exudes a high degree of professionalism vs. Does not appear to consider his or her professional image | 3.16 | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–5) | 0.015 |

| 3 | Has a broad range of life experience vs. has little practical life experience | 3.19 | 2 (2–5) | 3 (3–5) | <0.05 |

| 4 | Seeks a high degree of involvement with patients vs. Maintains a low degree of involvement with patients | 3.38 | 3 (1.25–5) | 5 (3–6) | <0.001 |

| 5 | Has a health education role vs. Role is unrelated to health education | 3.57 | 3 (1.75–5) | 4 (2–5) | 0.137 |

| 6 | Able to work with a wide spectrum of patient/client types vs. Able to work with only a narrow range of patient/client types | 3.90 | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2.5–6) | 0.039 |

| 7 | Communicates with many professionals vs. Communicates with few other professionals | 4.15 | 3 (2–6) | 5 (2–6) | 0.089 |

| 8 | Cares for the patient’s general wellbeing vs. Cares for the patient only in relation to his or her specific professional context | 4.43 | 5 (3–6) | 5 (3–6) | 0.166 |

| 9 | Builds a deep relationship with the patient vs. Has a more superficial relationship with the patient | 4.49 | 3 (2–5) | 5 (4–7) | <0.001 |

| 10 | Works effectively in a team vs. Works more effectively alone | 4.50 | 4 (2–6) | 5 (3–7) | 0.002 |

| 11 | Has an objective, medical perspective vs. Has a subjective, social perspective | 4.63 | 5 (3–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.289 |

| 12 | Requires a high level of technical skill vs. Requires a high level of intellectual skill | 4.72 | 5 (3–5) | 5 (3–6) | 0.123 |

| 13 | Has the ability to refer a patient to another professional vs. Works with the patient within his or her own professional field of knowledge | 4.90 | 4 (2–6) | 6 (4–8) | <0.001 |

| 14 | Possesses good interpersonal skills with an individual patient vs. Demonstrates good interpersonal skills within a group situation | 5.08 | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–7) | 0.167 |

| 15 | Medical focus of the work vs. Social focus of the work | 5.28 | 5 (4–6) | 5 (4–6) | 0.72 |

| 16 | Demonstrates a sense of humour when undertaking his or her role vs. Demonstrates a serious attitude when undertaking his or her role | 5.55 | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 0.76 |

| 17 | Works autonomously vs. Works with direction or supervision by another professional | 6.02 | 6 (5–8) | 6 (5–8) | 0.452 |

| 18 | Has a specific role that involves little collaboration with others vs. Engages in considerable collaboration with others | 8.53 | 10 (9–10) | 8 (6–9) | <0.001 |

| Item | Breadth of Professional Outlook | Projected Professional Image | Possesses Skills for a Wide Professional Scope | Degree of Professional Interdependence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | ||

| 1 | Communicates with many professionals vs. Communicates with few other professionals | 0.791 | |||

| 2 | Builds a deep relationship with the patient vs. Has a more superficial relationship with the patient | 0.719 | |||

| 3 | Able to work with a broad spectrum of patient/client types vs. Able to work with only a narrow range of patient/client types | 0.718 | |||

| 4 | Works effectively in a team vs. Works more effectively alone | 0.632 | |||

| 5 | Has a health education role vs. Role is unrelated to health education | 0.602 | |||

| 6 | Has the ability to refer a patient to another professional vs. Works with the patient within his or her own professional field of knowledge | 0.546 | |||

| 7 | Requires a high level of technical skill vs. Requires a high level of intellectual skill | 0.506 | |||

| 8 | Possesses good interpersonal skills with an individual patient vs. Demonstrates good interpersonal skills within a group situation | 0.491 | |||

| 9 | Role is clear and transparent to other professionals vs. Uncertainty among other professionals about what the role involves | 0.857 | |||

| 10 | Has a broad range of life experience vs. Has little practical life experience | 0.835 | |||

| 11 | Seeks out a high degree of involvement with the patient vs. Maintains a low degree of involvement with the patient | 0.703 | |||

| 12 | Exudes a high degree of professionalism vs. Does not appear to consider his or her professional image | 0.689 | |||

| 13 | Cares for the patient’s general wellbeing vs. Cares for the patient only in relation to his or her specific professional context | 0.497 | |||

| 14 | Demonstrates a sense of humour when undertaking his or her role vs. Demonstrates a serious attitude when undertaking his or her role | 0.684 | |||

| 15 | Medical focus of the work vs. Social focus of the work | 0.612 | |||

| 16 | Has an objective, medical perspective vs. Has a subjective, social perspective | 0.529 | |||

| 17 | Has a specific role that involves little collaboration with others vs. Engages in considerable collaboration with others | 0.718 | |||

| 18 | Works autonomously vs. Works with direction or supervision by another professional | 0.657 | |||

| Factors | Mean Score/SD | LT | EN | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breadth of Professional Outlook | 4.375 (3.375–5.375) | 3.875 | 4.898 | <0.001 |

| Projected Professional Image | 3.45 (2.5–4.8) | 2.8 | 4.29 | <0.001 |

| Possesses Skills for a Wide Professional Scope | 3.45 (2.5–4.8; 3.81) | 5.0 | 5.19 | 0.656 |

| Degree of Professional Interdependence | 7.5 (6–8.5) | 7.5 | 6.79 | <0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blaževičienė, A.; Vanckavičienė, A.; Paukštaitiene, R.; Baranauskaitė, A. Nurse’s Role from Medical Students’ Perspective during Their Interprofessional Clinical Practice: Evidence from Lithuania. Healthcare 2021, 9, 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080963

Blaževičienė A, Vanckavičienė A, Paukštaitiene R, Baranauskaitė A. Nurse’s Role from Medical Students’ Perspective during Their Interprofessional Clinical Practice: Evidence from Lithuania. Healthcare. 2021; 9(8):963. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080963

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlaževičienė, Aurelija, Aurika Vanckavičienė, Renata Paukštaitiene, and Asta Baranauskaitė. 2021. "Nurse’s Role from Medical Students’ Perspective during Their Interprofessional Clinical Practice: Evidence from Lithuania" Healthcare 9, no. 8: 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080963

APA StyleBlaževičienė, A., Vanckavičienė, A., Paukštaitiene, R., & Baranauskaitė, A. (2021). Nurse’s Role from Medical Students’ Perspective during Their Interprofessional Clinical Practice: Evidence from Lithuania. Healthcare, 9(8), 963. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9080963