Acne Vulgaris and Intake of Selected Dietary Nutrients—A Summary of Information

Abstract

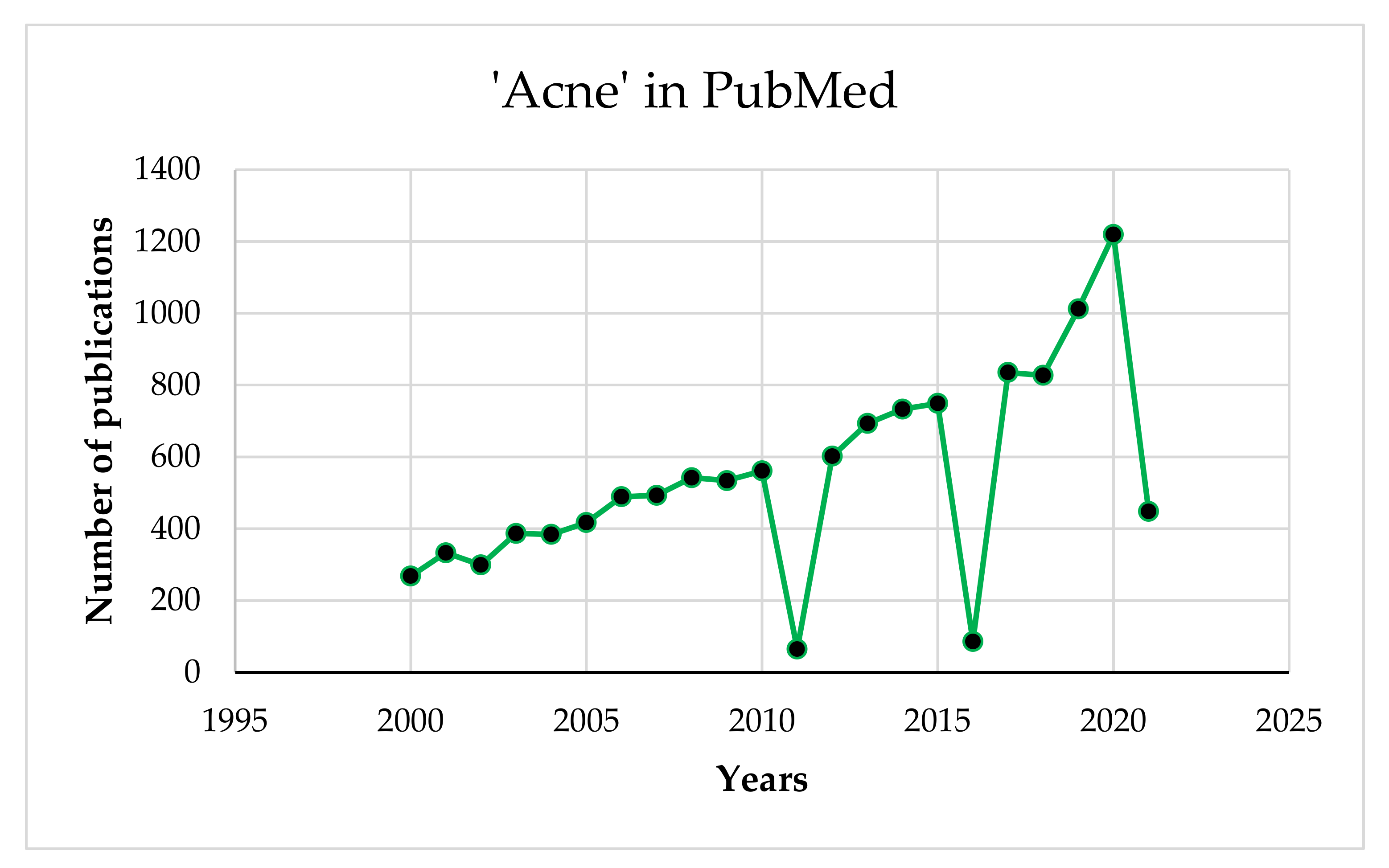

1. Introduction

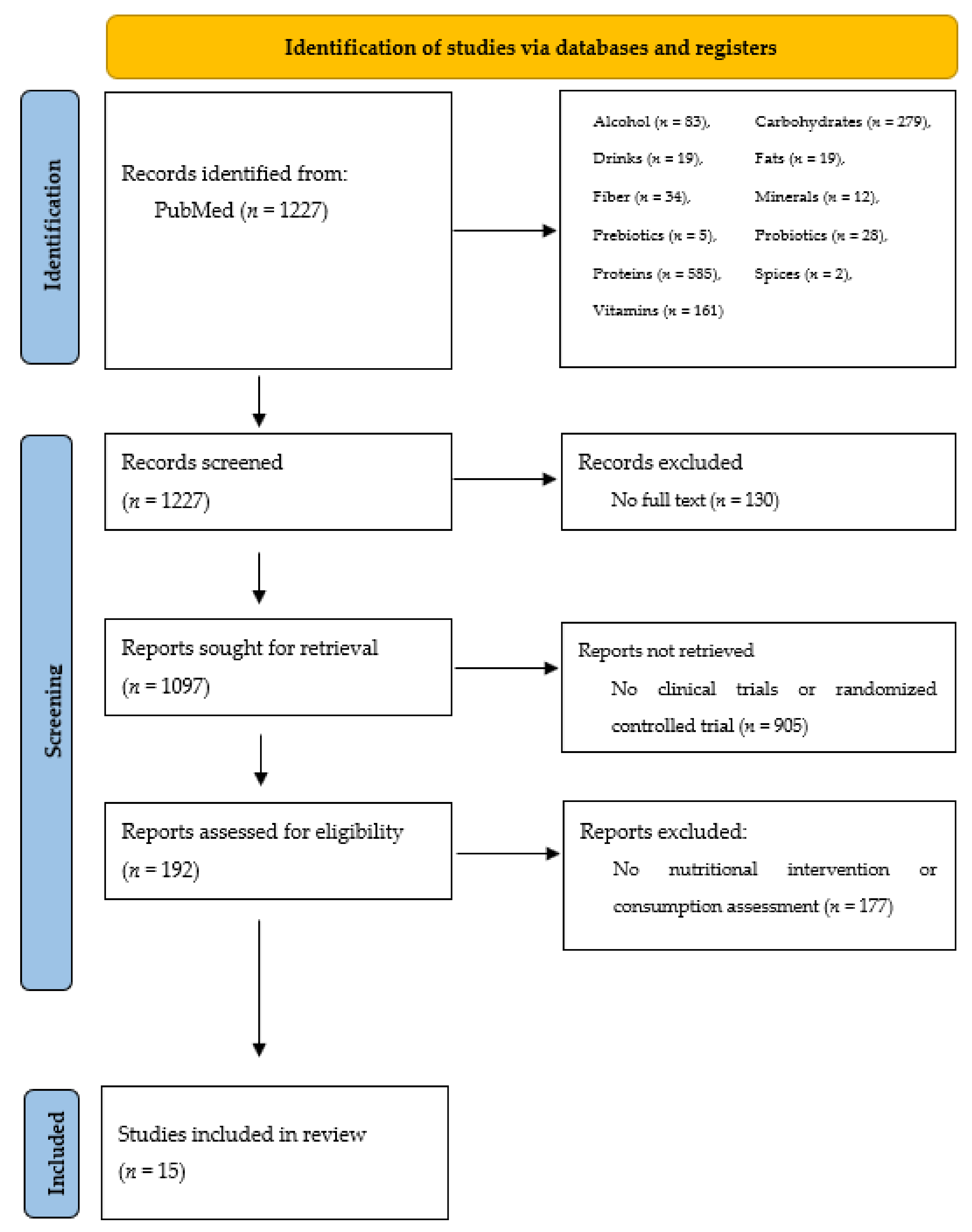

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Carbohydrates

4.2. Fibre

4.3. Proteins

4.4. Fats

4.5. Vitamins

4.6. Minerals

4.7. Probiotics and Prebiotics

4.8. Other Important Ingredients in the Diet

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Urbanowski, S.W.; Krajewska-Kułak, E. Dermatologia i wenerologia dla pielęgniarek. In Dermatology and Venereology for Nurses; CZELEJ: Lublin, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, Z.; Kaszuba, A. Dermatologia dla kosmetologów. In Dermatology for Cosmetologists; Urban & Partner: Wrocław, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Janda, K.; Chwiłkowska, M. Trądzik pospolity-etiologia, klasyfikacja, leczenie [Acne vulgaris-etiology, classification, treatment]. Rocz. Pomor. Akad. Med. Szczec. 2014, 60, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burris, J.; Shikany, J.M.; Rietkerk, W.; Woolf, K. A low glycemic index and glycemic load diet decreases insulin-like growth factor-1 among adults with moderate and severe acne: A short-duration, 2-week randomized controlled trial. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1874–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.; Chan, G.; Santos, J.; Dee, K.; Co, J.K. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to determine the efficacy and safety of lactoferrin with vitamin E and zinc as an oral therapy for mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Int. J. Dermatol. 2017, 56, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.K.; Ha, J.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.; Seo, Y.J.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, J.H.; Im, M. Comparison of vitamin D levels in patients with and without acne: A case-control study combined with a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabbrocini, G.; Cameli, N.; Lorenzi, S.; De Padova, M.P.; Marasca, C.; Izzo, R.; Monfrecola, G. A dietary supplement to reduce side effects of oral isotretinoin therapy in acne patients. G. Ital. Dermatol. Venereol. 2014, 149, 441–445. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.Y.; Kwon, H.H.; Hong, J.S.; Yoon, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Jang, M.Y.; Suh, D.H. Effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acid and gamma-linolenic acid on acne vulgaris: A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2014, 94, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, G.W.; Tse, J.E.; Guiha, I.; Rao, J. Prospective, randomized, open-label trial comparing the safety, efficacy, and tolerability of an acne treatment regimen with and without a probiotic supplement and minocycline in subjects with mild to moderate acne. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2013, 17, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalita, A.R.; Falcon, R.; Olansky, A.; Iannotta, P.; Akhavan, A.; Day, D.; Janiga, A.; Singri, P.; Kallal, J.E. Inflammatory acne management with a novel prescription dietary supplement. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012, 11, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H.H.; Yoon, J.Y.; Hong, J.S.; Jung, J.Y.; Park, M.S.; Suh, D.H. Clinical and histological effect of a low glycaemic load diet in treatment of acne in Korean patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2012, 92, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, E.A.; Trapp, S.; Frentzel, A.; Kirch, W.; Brantl, V. Efficacy and tolerability of oral lactoferrin supplementation in mild to moderate acne vulgaris: An exploratory study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2011, 27, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ko, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Kim, N.I.; Ha, W.K.; Cho, Y. Dietary effect of lactoferrin-enriched fermented milk on skin surface lipid and clinical improvement of acne vulgaris. Nutrition 2010, 26, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, R.C.; Lee, S.; Choi, J.Y.; Atkinson, F.S.; Stockmann, K.S.; Petocz, P.; Brand-Miller, J.C. Effect of the glycemic index of carbohydrates on Acne vulgaris. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.N.; Braue, A.; Varigos, G.A.; Mann, N.J. The effect of a low glycemic load diet on acne vulgaris and the fatty acid composition of skin surface triglycerides. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2008, 50, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.N.; Mann, N.J.; Braue, A.; Mäkeläinen, H.; Varigos, G.A. The effect of a high-protein, low glycemic-load diet versus a conventional, high glycemic-load diet on biochemical parameters associated with acne vulgaris: A randomized, investigator-masked, controlled trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 57, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.N.; Mann, N.J.; Braue, A.; Mäkeläinen, H.; Varigos, G.A. A low-glycemic-load diet improves symptoms in acne vulgaris patients: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 86, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, S.; Gün, D.; Demirçay, Z.; Sur, H. Vitamin E does not reduce the side-effects of isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. Int. J. Dermatol. 2005, 44, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.; Mann, N.; Mäkeläinem, H.; Roper, J.; Braue, A.; Varigos, G. A pilot study to determine the short-term effects of a low glycemic load diet on hormonal markers of acne: A nonrandomized, parallel, controlled feeding trial. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebamowo, C.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Danby, F.W.; Frazier, A.L.; Willett, W.C.; Holmes, M.D. High school dietary dairy intake and teenage acne. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2005, 52, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebamowo, C.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Berkey, C.S.; Danby, F.W.; Rocket, H.H.; Coldits, G.A.; Wilett, W.C.; Holmes, M.D. Milk consumption and acne in adolescent girls. Dermatol. Online 2006, 12, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Suppiah, T.S.S.; Sundram, T.K.M.; Tan, E.S.S.; Lee, C.K.; Bustami, N.A.; Tan, C.K. Acne vulgaris and its association with dietary intake: A Malaysian perspective. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 27, 1141–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Akpinar Kara, Y.A.; Ozdemir, D. Evaluation of food consumption in patients with acne vulgaris and its relationship with acne severity. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2019, 19, 2109–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonart, T. Acne and whey protein supplementation among bodybuilders. Dermatology 2012, 225, 256–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed Mohamed, A.; Salah Ahmed, E.M.; Abdel-Aziz, R.T.A.; Abdallah, H.H.E.; El-Hanafi, H.; Hussein, G.; Abbassi, M.M.; Borolossy, R.E. The impact of active vitamin D administration on the clinical outcomes of acne vulgaris. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 2020, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Moclair, B.; Hatcher, V.; Kaminetsky, J.; Mekas, M.; Chapas, A.; Capodice, J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of a novel pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement in subjects with mild to moderate facial acne. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 4, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozuguz, P.; Dogruk Kacar, S.; Ekiz, O.; Takci, Z.; Balta, I.; Kalkan, G. Evaluation of serum vitamins A and E and zinc levels according to the severity of acne vulgaris. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Anbari, H.H.; Sahib, A.S.; Abu Raghif, A.R. Effects of silymarin, N-acetylocysteine and selenium in the treatment of papulopustular acne. Oxid. Antioxid. Med. Sci. 2012, 1, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmayani, T.; Putra, I.B.; Jusuf, N.K. The effect of oral probiotic on the interleukin-10 serum levels of acne vulgaris. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 7, 3249–3252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dall’Oglio, F.; Milani, M.; Micali, G. Effects of oral supplementation with FOS and GOS prebiotics in women with adult acne: The “S.O. Sweet” study: A proof-of-concept pilot trial. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2018, 11, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jing, D.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Su, J.; et al. Daily intake of soft drinks and moderate-to-severe acne vulgaris in Chinese adolescents. J. Pediatr. 2019, 204, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Darouti, M.A.; Zeid, O.A.; Abdel Halim, D.M.; Hegazy, R.A.; Kadry, D.; Shehab, D.I.; Abdelhaliem, H.S.; Saleh, M.A. Salty and spicy food; are they involved in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris? A case controlled study. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2016, 15, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.H.; Hsu, C.H. Does supplementation with green tea extract improve acne in post-adolescent women? A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 2016, 25, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawęcki, J.; Hryniewiecki, L. Human Nutrition. Vol. I. Basics of Nutrition Science; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, B.C.; Schmitz, G. Role of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-1, hyperglycaemic food and milk consumption in the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, M.; Sajór, I.; Gugała-Mirosz, S.; Nagel, P. Czy wiesz, ile potrzebujesz węglowodanów? In Do You Know How Many Carbohydrates You Need? Instytut Żywności i Żywienia: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kunachowicz, H.; Przygoda, B.; Nadolna, I.; Iwanow, K. Tabele składu i wartości odżywczej żywności. In Food Composition and Nutrition Tables, 2nd ed.; PZWL: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zimecki, M.; Kruzel, M.L. Milk-derived proteins and peptides of potential therapeutic and nutritive value. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 2007, 6, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Piejko, L. Mleko, białka mleka a trądzik. Milk, milk proteins and acne. Pol. J. Cosmetol. 2018, 21, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Melnik, B.C. Linking diet to acne metabolomics, inflammation, and comedogenesis: An update. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarosz, M. Normy żywienia dla populacji Polski. In Nutrition Standards for the Polish Population; Instytut Żywności i Żywienia: Warszawa, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Picardo, M.; Ottaviani, M.; Camera, E.; Mastrofrancesco, A. Sebaceous gland lipids. Dermatoendocrinology 2009, 1, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojarowicz, H.; Woźniak, B. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their effect on the skin. Probl. Hig. Epidemiol. 2008, 89, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalska, H.; Sysa-Jędrzejowska, A.; Woźnicka, A. Role of diet in the aetiopathogenesis of acne. Przegl. Dermatol. 2018, 105, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cichosz, G.; Czeczot, H. Trans isomerism fatty acids in the human diet. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol. 2012, 45, 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Sorg, O.; Kuenzli, S.; Kaya, G.; Saurat, J.H. Proposed mechanism of action for retinoid derivatives in the treatment of skin aging. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2005, 4, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traikovich, S.S. Use of topical ascorbic acid and its effects on photodamaged skin topography. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1999, 125, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, P.K. Cosmetical vitamins: Vitamin C. In Cosmeceuticals. Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology, 2nd ed.; Draelos, Z.D., Dover, J.S., Alam, M., Eds.; Saunders Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D metabolism and function in the skin. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2011, 347, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balta, I.; Ozuguz, P. Vitamin B12—Induced acneiform eruption. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veraldi, S.; Benardon, S.; Diani, M.; Barbareschi, M. Acneiform eruptions caused by vitamin B12: A report of five cases and review of the literature. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Suh, D.H.; Kim, B.Y.; Min, S.U.; Lee, D.H.; Yoon, M.Y.; Kim, N.I.; Kye, Y.C.; Lee, E.S.; Ro, Y.S.; Kim, K.J. A multicenter epidemiological study of acne vulgaris in Korea. Int. J. Dermatol. 2011, 50, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | Type of Acne | Type of Study | Intervention/Measurement | Duration | Effect | Year [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 | moderate to severe AV | randomised controlled trial | -group 1: n = 34–participants with low GI and GL diet -group 2: n = 32–participants with usual eating diet | 2 weeks | -IGF-1 concentrations significantly decreased among the group with low GI and GL diets and control group -there were no significant differences in insulin, glucose, IGFBP-3 concentrations and insulin resistance | 2018 [5] |

| 168 | mild to moderate AV | randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | -group A (n = 82): capsules containing lactoferrin (100 mg), vitamin E (11 IU, as alpha-tocopherol), and zinc (5 mg, as zinc gluconate), capsule twice a day -group B (n = 82): placebo, capsules containing starch, capsule twice a day | 12 weeks | -in the lactoferrin group, compared to the control: significant reduction in the total number of lesions (already after 2 weeks, with a maximum: at week 10), reduction in comedones and inflammatory changes (at week 10), sebum (improvement by week 12) | 2017 [6] |

| 160 | nd | case-control study with a randomised controlled trial | n = 80 patients n = 80 healthy controls 1st stage: 25 (OH) D deficiency in 48.8% of AV patients, but only 22.5% of healthy controls 2nd stage: supplementation of 1000 IU of cholecalciferol/day | 2 months | -deficiency of vitamin D was more frequent in patents with AV, oral vitamin D supplementation significantly improved AV inflammation | 2016 [7] |

| 48 | nodular acne | randomised controlled trial | n = 24 patients received isotretinoin therapy (20–30 mg/day) and dietary supplement (gamma linolenic acid, vitamin E, vitamin C, beta-carotene, coenzyme Q10 and Vitis vitifera, twice a day) n = 24 patients received only isotretinoin (20–30 mg/day) | 6 months | -patients using a dietary supplement with antioxidant properties had fewer side effects resulting from the use of isotretinoin, less redness and dryness and a better degree of hydration | 2014 [8] |

| 45 | mild to moderate AV | randomised controlled trial | -group I: 2000 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid) -group II: borage oil containing 400 mg γ-linoleic acid),III: a control group | 10 weeks | -subjective assessment of improvement -reduction in inflammation and non-inflammatory acne lesions | 2014 [9] |

| 45 | mild to moderate AV | prospective, randomised, open-label trial | -group A: probiotic -group B: minocycline -group C: probiotic and minocycline | 12 weeks | -a significant improvement in the total number of lesions 4 weeks after the start of treatment in all groups -after 8 and 12 weeks, group C had a significant decrease in the total number of lesions compared to groups A and B | 2013 [10] |

| 235 | inflammatory AV | multi-centre, open-label, prospective study | -addition of 1 to 4 tablets NicAzel (nicotinamide, azelaic acid, zinc, pyridoxine, copper, folic acid) to the current acne treatment regimen | 8 weeks | -visible reduction in inflammatory changes (88% of patients), and 81% of patients rated skin appearance as moderate or much better | 2012 [11] |

| 32 | mild to moderate AV | randomised, controlled trial | n = 17–low-glycaemic-load diet n = 15–control group | 10 weeks | -significant clinical improvement in the number of non-inflammatory and inflammatory AV lesions (in the low-glycaemic index group) | 2012 [12] |

| 43 | mild to moderate | exploratory study | 100 mg of lactoferrin-enriched (80%) whey milk protein powder, twice a day | 8 weeks | -reduction in inflammatory lesions (20.2%), non-inflammatory lesions (23.5%) and total lesions (22.5%), reduction in total lesion count (76.9%) | 2011 [13] |

| 36 | mild to moderate | double-blind, placebo-controlled study | n = 18–lactoferrin group (200 mg daily) n = 18–placebo group | 12 weeks | -a significant reduction in acne severity (by 20.3%), number of inflammatory lesions (by 38.6%) and total lesions (by 23.1%) compared to the placebo group | 2010 [14] |

| 58 | 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), or 3 (severe) | controlled clinical trial | n = 23–low glycaemic index n = 20–high glycaemic index | 8 weeks | -improvement in the appearance of the skin (but not statistically significant), change in insulin sensitivity (but not statistically significant) | 2010 [15] |

| 31 | mild to moderate AV | dietary intervention trial | n = 16, LGL group n = 15–control group | 12 weeks | -increases in the ratio of saturated to monounsaturated fatty acids of skin surface triglycerides compared to controls | 2008 [16] |

| 43 | mild to moderate | randomised, investigator-masked, controlled trial | n = 23–LGL group, n = 20–control group | 12 weeks | -decrease in the total number of lesions, body weight, free androgen index and increase in insulin-like growth factor-1 binding protein compared to the control group | 2007 [17] |

| 43 | mild to moderate | non-randomised, parallel, controlled feeding trial | n = 23, patients: LGL diet (25% energy from proteins, 45% energy from carbohydrates) n = 20, control group: diet rich with carbohydrates, but without reference to the glycaemic index | 12 weeks | -decrease in the total number of lesions, decrease in body weight and body mass index, greater improvement in insulin sensitivity-compared to the control group | 2007 [18] |

| 82 | severe AV, moderate AV unresponsive to conventional therapy, scarring AV, and AV causing psychological disorder | investigator-blinded, randomised study | group 1: isotretinoin (1 mg/kg/day) group 2: isotretinoin (1 mg/kg/day) and vitamin E (800 IU/day) | 16 weeks | -vitamin E did not reduce the side effects associated with the use of isotretinoin | 2005 [19] |

| n | Type of Study | Intervention/Measurement/Methods | Duration | Effect | Year [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | |||||

| 12 | randomised, controlled trial | low glycaemic load diet (LGL) or high glycaemic load diet (HGL) | 12 weeks | -changes in the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR): −0.57 for LGL vs. 0.14 for HGL -changes in sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG): SHBG levels decreased significantly from baseline in the HGL group -changes in binding proteins (IGFBP-I and IGFBP-3): IGFBP-I and IGFBP-3 levels increased in the LGL group | 2008 [20] |

| Proteins | |||||

| 47,355 | prospective cohort study | assessment of the association of milk consumption with the occurrence of AV | questionnaires on high school diet | a positive relationship between the consumption of whole and skimmed milk and the incidence of AV | 2005 [21] |

| 6094 | prospective cohort study | association of correlation between drinking milk and AV | nd | -positive association between the intake of milk and AV | 2006 [22] |

| 114 | case-control study | intake assessment–food intake questionnaire n = 57 patients n = 57 control group | nd | -milk and chocolate consumption were significantly higher in patients with AV | 2018 [23] |

| 106 | case-control study | dietary intake of milk and dairy products along with carbohydrate/ fat/protein ratios n = 53 patients n = 53 control group | 3 day (2 weekdays and 1 weekend day) consumption record | -statistically higher consumption of cheese in people with AV | 2019 [24] |

| 5 | case report | developing AV after the consumption of whey protein | 5.6 ± 1.8 months | -milk and dairy products were enhancers of insulin/insulin-like growth factor 1 signalling and AV aggravation | 2012 [25] |

| Vitamins | |||||

| 200 | prospective, randomised, controlled and open label trial | investigated the serum level of 25-hydroxy vitamin D in AV patients and assessment of the efficacy and safety of active vitamin D in management of AV n = 100 patients n = 100 control group | 3 months | -serum levels of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D were lower in AV patients than in healthy controls -AV patients were more likely to have a vitamin D deficiency than healthy people | 2020 [26] |

| 48 | randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | determination of the safety, tolerability and effectiveness of daily administration of an orally administered pantothenic acid-based dietary supplement in men and women with facial AV lesions n = 23 patients, n = 25 placebo group | 12 weeks | -reduction in total lesion count in the pantothenic acid group versus placebo -reduction in inflammatory lesions was significantly reduced -dermatology life quality index (DLQI) values were lower at week 12 in the pantothenic acid group versus placebo | 2014 [27] |

| Vitamins and Minerals | |||||

| 150 | observational study | evaluation of plasma levels of vitamin A, E and zinc in AV patients in relation to the severity of the disease n = 94 patients n = 56 control group | nd | -levels of vitamin E, vitamin A and zinc were lower among patients than in the control group -no statistically significant difference for plasma vitamin A levels between group 1 and 2 -vitamin E and zinc levels were significantly lower in group 2 than group 1 | 2014 [28] |

| Minerals | |||||

| 56 | randomised prospective clinical trial | group 1 (n = 14): silymarin (3 × 70 mg/day) group 2 (n = 14): N-acetylcysteine (2 × 600 mg/day) | 8 weeks | -silymarin, N-acetylcysteine and selenium with AV significantly reduced serum MDA, IL-8 levels and the number of inflammatory lesions | 2012 [29] |

| group 3 (n = 14): selenium (2 × 100 µg/day) | |||||

| Probiotics and Prebiotics | |||||

| 33 | pre-experimental clinical study | probiotics | 30 days | -oral probiotic trigger elevated IL-10 serum levels of AV | 2019 [30] |

| 12 | proof-of-concept pilot study | FOS (fructo-oligosaccharides) and GOS (galactooligosaccharodes | 3 months | -FOS/GOS supplementation in people with baseline insulin levels > 6 µUI/mL (n = 6) caused a significant reduction (from 7.8 to 4.3 µUI/mL) -concentration of C-peptide decreased from 2.1 to 1.6 ng/mL | 2018 [31] |

| Other Factors | |||||

| 8197 | epidemiologic investigation | association of soft drink consumption and intake of sugar from these drinks with prevalence of AV in adolescents | nd | -daily soft drink consumption increased the risk of moderate to severe AV in adolescents, mainly when sugar intake from this drink exceeded 100 g per day | 2019 [32] |

| 400 | case controlled study | relationship between dietary intake of salty and spicy foods and the onset, severity and duration of AV n = 200 patients, n = 200 control group | 24 h questionnaire | -patients with AV consumed higher daily amounts of sodium chloride (NaCl) than the control group -a negative correlation between the amount of NaCl in the diet of patients with AV was found -neither salty nor spicy food correlated with duration or severity of the disease | 2016 [33] |

| 80 | randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial | -effects of a decaffeinated green tea extract (GTE) upon women with post-adolescent AV -receiving 1500 mg per day of decaffeinated GTE or cellulose for placebo group for 4 weeks n = 40–GTE group n = 40–placebo group | 4 weeks | -statistically significant differences in inflammatory lesion counts distributed on the nose, periorally, and on the chin between the two groups -no significant differences between groups for total lesion counts -significant reductions in inflammatory lesions distributed on the forehead and cheek, and significant reductions in total lesion counts noticed in the GTE group -significant reductions in total cholesterol levels within the GTE group | 2016 [34] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Podgórska, A.; Puścion-Jakubik, A.; Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Gromkowska-Kępka, K.J.; Socha, K. Acne Vulgaris and Intake of Selected Dietary Nutrients—A Summary of Information. Healthcare 2021, 9, 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060668

Podgórska A, Puścion-Jakubik A, Markiewicz-Żukowska R, Gromkowska-Kępka KJ, Socha K. Acne Vulgaris and Intake of Selected Dietary Nutrients—A Summary of Information. Healthcare. 2021; 9(6):668. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060668

Chicago/Turabian StylePodgórska, Aleksandra, Anna Puścion-Jakubik, Renata Markiewicz-Żukowska, Krystyna Joanna Gromkowska-Kępka, and Katarzyna Socha. 2021. "Acne Vulgaris and Intake of Selected Dietary Nutrients—A Summary of Information" Healthcare 9, no. 6: 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060668

APA StylePodgórska, A., Puścion-Jakubik, A., Markiewicz-Żukowska, R., Gromkowska-Kępka, K. J., & Socha, K. (2021). Acne Vulgaris and Intake of Selected Dietary Nutrients—A Summary of Information. Healthcare, 9(6), 668. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060668