Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital, Malaysia

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Pandemic is not a word to use lightly or carelessly. It is a word that, if misused, can cause unreasonable fear, or unjustified acceptance that the fight is over, leading to unnecessary suffering and death.”[1]

1.1. University Malaya Medical Centre as the COVID-19 Healthcare Provider

1.2. Remote Psychological First Aid for Frontliners

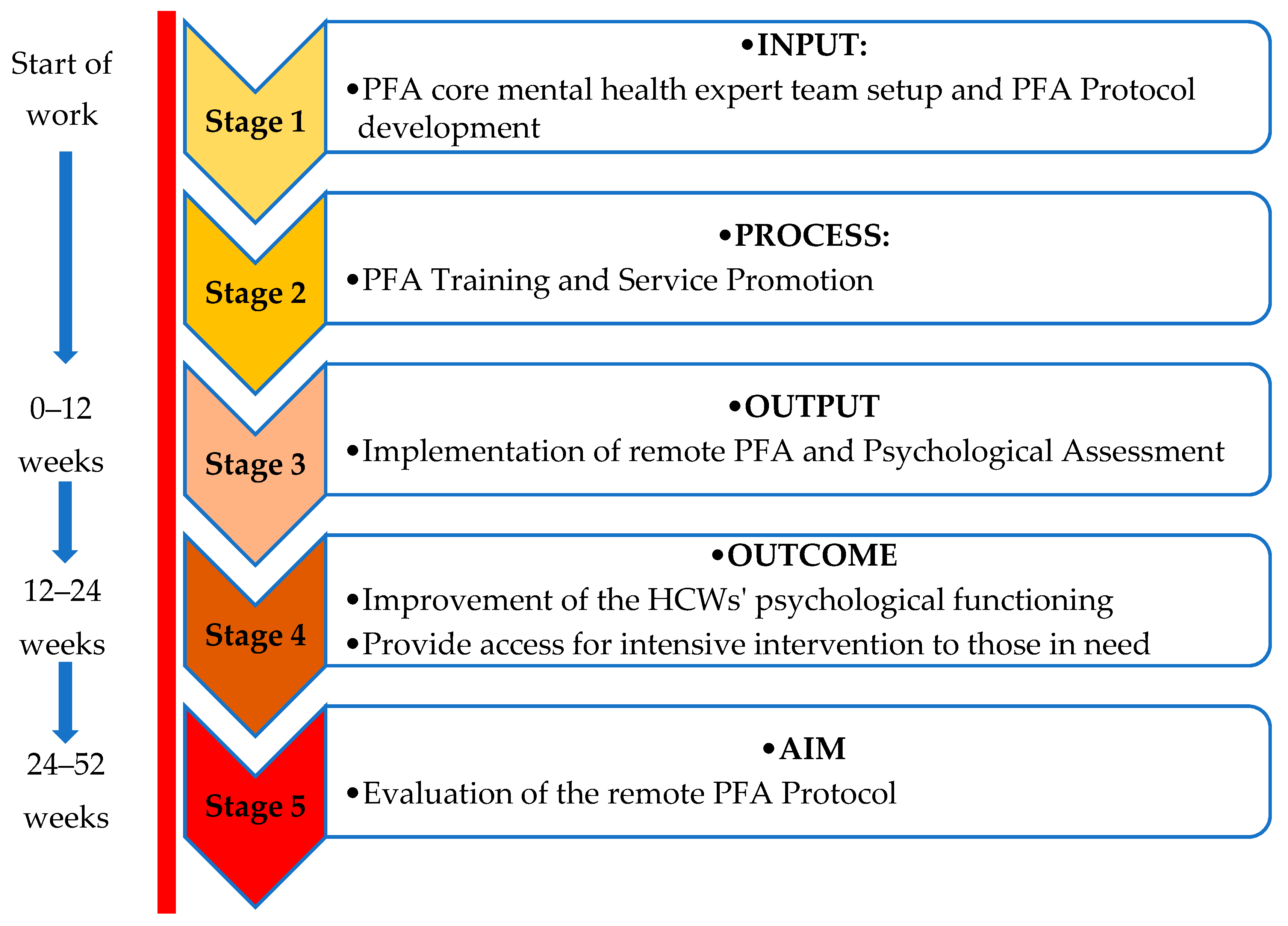

1.3. Stepwise Remote PFA Framework for SMART Output, Outcome, and Aim

- i.

- to provide PFA training to mental health experts (psychiatrist, psychologist, counsellor) as PFA providers based on COVID-19 PFA guidelines;

- ii.

- to provide early remote PFA to consenting frontliners via telepsychiatry;

- iii.

- to encourage healthcare workers to get psychological help through online promotion and awareness campaigns and to minimize stigma;

- iv.

- to measure quantitatively the level of depression, anxiety, distress, and burnout in frontliners through online assessment while maintaining confidentiality;

- v.

- to provide access to more intensive intervention for those who require it;

- vi.

- to review and evaluate the protocol within a stipulated time frame.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Development for Remote PFA: Stepwise Process Implementation and Expected Immediate, Intermediate, and Long-Term Goals

2.1.1. Stage 1: Input—PFA Core Mental Health Expert Team Set-Up and Remote PFA Protocol Development

- Identification of the needs of the HCWs: All identified HCWs who consented to the remote PFA are assessed to make sure that they have access to the WhatsApp mobile application for referral to be made to the PFA Provider and for on-line psychological screening (pre- and post-PFA). Any issues regarding accessibility to the service will be managed by the Task Force sub-committee.

- Identification of the needs of the PFA providers: The hospital provides a mobile phone for the PFA provider on duty. WhatsApp messages will be used for initial communications by the provider to introduce the protocol and develop an interaction with the HCW. Once the rapport is established, the mode of communication will be through phone calls that can be either a one-off call or follow-up calls, depending on the HCW’s needs.

- Sufficient number of mental health experts as PFA providers: A total of 14 psychiatrists, 6 psychologists, and a counsellor agreed to participate, allowing a daily schedule of interventions for 12 weeks.

- Identification of PFA trainers and sessions: three PFA trained mental health experts were identified who were responsible for half-a-day training.

- Realistic time frame: The hospital management orders the rescheduling of psychiatrist, psychologist, and counsellor ambulatory services for 12 weeks, which allows the PFA providers to focus on the PFA services within the stipulated time frame.

- Identification of the measurement tool: The team agreed on the use of the DASS-21 (Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale) and CBI (Copenhagen Burnout Inventory) as the psychological assessment tools pre- and post-PFA.

2.1.2. Stage 2: Process—Intensive Remote PFA Training and Service Promotion

- The use of WhatsApp mainly for seeking immediate clarification and permission to initiate the session immediately after referral from the CDCU;

- The use of phone calls as a means of conducting and terminating a session;

- The need of the PFA provider to develop the skill of empathic and reflective listening during conversations via phone calls, especially when dealing with acutely distressed, angry, or confused HCWs.

- Maintaining personal and verbal conduct throughout the sessions since both the provider and the HCW may have to overcome own difficulties, such as possible tensions which require the provider to stay calm, despite her/his own fear of COVID-19.

- Understanding the aim of PFA, which is to promote safety, calm, hope, and connectedness, in contrast to debriefing [13].

- Introduction of the eight-core actions of PFA as part of the “Look, Listen, Link” principle, adapted from the conventional face-to-face PFA [11]). These elements of the PFA are introduced as an overview of the PFA core actions to enhance knowledge and highlight the practical aspects of these PFA principles prior to implementation during the COVID-19 outbreak (Table 1).

2.1.3. Stage 3: Output—Implementation of Remote PFA, Psychological Assessment of the Frontliners

- Specific output: The PFA providers can provide telepsychiatry interventions confidently and responsibly within 24 h of receiving referral via WhatsApp. The HCWs that fulfil the criteria for referral to PFA providers consented to the intervention and undergo a mental health screening using DASS-21 and CBI.

- Measurable output: The level of depression, anxiety, distress, and burnout of the HCWs are measured immediately upon referral via the online form and 2 weeks after PFA completion.

- Attainable output: Each HCW is distributed by the CDCU manager in a 1:1:1 ratio among the psychiatrists, psychologists, and counselors.

- Relevant and realistic timeframe output: The remote PFA intervention is still relevant due to the protracted nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. The establishment of a short-term goal within 12 weeks is practical and realistic.

2.1.4. Stage 4: Outcome—Improvement of the HCWs’ Psychological Functioning and Accessibility to Intensive Interventions for Severe Cases

- Specific outcome: All HCWs who consented to the remote PFA intervention are attended to by mental health experts (PFA providers) via WhatsApp and phone calls. All HCWs with severe psychological and social needs are referred to relevant experts.

- Measurable outcome: The data collected from the CDCU on HCWs’ DASS-21 and CBI are analyzed quantitatively for the psychological impact of COVID-19 before and after the intervention. The level of psychological distress and/or burnout will improve between 30% to 50%. (At the time of writing, the process is still ongoing).

- Attainable outcome: The number of mental health experts (psychiatrists, psychologists, and counsellors) to provide psychosocial crisis interventions for HCWs is adequate and is supported by the organization top management.

- Relevant and realistic timeframe outcome: A period of 12 weeks is considered realistic to achieve all the objectives successfully, and due to the protracted nature of COVID-19, the remote PFA may remain relevant up to 24 weeks.

2.1.5. Stage 5: Aim—Evaluation of the Remote PFA Protocol

- Specific aim: Every stages of the protocol is evaluated by experts from Psychological Medicine, Occupational Safety and Environmental Health, Public Health, Nursing, as well as administrative representatives from UMMC with regard to the work process, data management, and preparedness of the mental health experts (PFA providers and trainers).

- Measurable aim: Validated tools are identified by experts in epidemiology and industrial and organization psychologists to specifically assess the work-related distress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Attainable aim: Virtual psychological interventions within the boundaries of medical ethics and hospital policy are developed by information technology experts, mental health experts, legal advisors, and representatives of stakeholders identified by UMMC.

- Relevant and realistic timeframe aim: An action plan that includes a feasibility study of remote psychological crisis interventions using a virtual technology protocol may further improve the training and service delivery within the next two to four years.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 -March 2020. Available online: www.who.int/COVID-19/information (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Majlis Keselamatan Negara. Perintah Kawalan Pergerakan (Movement Control Order): Kuatkuasa Undang-undang. Available online: https://www.mkn.gov.my/web/ms/covid-19/ (accessed on 19 March 2020).

- Santos, J. Refections on the impact of “fatten the curve” on interdependent workforce sectors. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.P.; Sam, I.C. Behavioral responses to the influenza A (H1N1) outbreak in Malaysia. J. Behav. Med. 2011, 34, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.; Haque, S.; Neto, F.; Myers, L.B. Initial psychological responses to Influenza A, H1N1 (swine flu). BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoji, K.; Lesnierowska, M.; Smoktunowicz, E.; Bock, J.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, B.C. What comes first, job burnout or secondary traumatic stress? Findings from two longitudinal studies from the U.S. and Poland. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; McGoogan, J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 90,000 HCW Infected with COVID-19: ICN. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/90-000-healthcare-workers-infected-with-covid-19-icn/1831765 (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control during Health Care When COVID-19 Is Suspected. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125 (accessed on 7 May 2020).

- World Health Organization; War Trauma Foundation; World Vision International. Psychological First Aid: Guide for Field Workers; WHO: Geneva, Sweden; Available online: https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/guide_field_workers/en/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Forbes, D.; Lewis, V.; Varker, T.; Phelps, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Wade, D.J.; Ruzek, J.I.; Watson, P.; Bryant, R.A.; Creamer, M. Psychological First Aid Following Trauma: Implementation and Evaluation Framework for High-Risk Organizations. Psychiatry 2011, 74, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, W. Recommended psychological crisis intervention response to the 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia outbreak in China: A model of West China Hospital. Precis. Clin. Med. 2020, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remote Psychological First Aid during a COVID-19 Outbreak, Final Guidance Notes. Available online: https://pscentre.org/?resource=remote-psychological-first-aid-during-the-covid-19-outbreak-interim-guidance-march-2020 (accessed on 20 April 2020).

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bipp, T.; Kleingeld, A. Goal setting in practice: The effects of personality and perceptions of the goal setting process on job satisfaction and goal commitment. Pers. Rev. 2011, 40, 306–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiell, A. Health outcomes are about choices and values: An economic perspective on the health outcomes movement. Health Policy 1997, 39, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersh, D.; Worrall, L.; Howe, T.; Sherratt, S.; Bronwyn, D. SMARTER goal setting in aphasia rehabilitation. Aphasiology 2012, 26, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.P.; Crowe, T.P.; Oades, L.G.; Deane, F.P. Do goal-setting interventions improve the quality of goals in mental health services? Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2009, 32, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, J.; Mogensen, L.; Marsland, E. The development, content validity and inter-rater reliability of the SMART-Goal Evaluation Method: A standardised method for evaluating clinical goals. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2015, 62, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbeiwi, O. Why written objectives need to be really SMART. Br. J. Healthc. Manag. 2017, 23, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Watson, P.; Bell, C.C.; Bryant, R.A.; Brymer, M.J.; Friedman, M.J.; Friedman, M.; Gersons, B.P.R.; de Jong, J.T.V.M.; Layne, C.M.; et al. Five Essential Elements of Immediate and Mid–Term Mass Trauma Intervention: Empirical Evidence. Psychiatry 2007, 70, 283–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, R.; Ramli, R.; Abdullah, K.; Sarkarsi, R. Concurrent Validity of The Depression and Anxiety Components in The Bahasa Malaysia Version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (Dass). ASEAN J. Psychiatry 2014, 12, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, B.; Rizal, A.J.; Sabki, Z.A.; Sulaiman, A.H. Remote Psychological First Aid (rPFA) in the time of Covid-19: A preliminary report of the Malaysian experience. Asian J. Psychiatry 2020, 54, 102240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, T.S.; Borritz, M.; Villadsen, E.; Christensen, K.B. The Copenhagen Burnout Inventory: A new tool for the assessment of burnout. Work Stress 2005, 19, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manual on Mental Health and Psychosocial Response to Disaster in Community. Mental Health Unit, Non-Communicable Disease Section, Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.my/ (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Dückers, M.L.A. Five essential principles of post-disaster psychosocial care: Looking back and forward with Stevan Hobfoll. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol 2013, 4, 21914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogbeiwi, O. General Concepts of goals and goal-setting in healthcare: A narrative review. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Core Actions | Targeted Goals with Remote PFA |

|---|---|

| 1. Contact and Engagement | All HCWs who consented to the remote PFA intervention, are attended to by PFA providers via a WhatsApp phone call within 24 h of referral. PFA is offered once therapeutic alliance is formed, but if help is declined, respect the wish but explain that help is always available. |

| 2. Comfort and Safety | HCWs receive immediate emotional support that promotes sense of safety, comfort, and hope. |

| 3. Calm and Stabilization | HCWs is able to self-regulate her/his own emotions through breathing, relaxation techniques, and self-affirmative words during crises. |

| 4. Collect Information of Current Needs and Concerns | The immediate needs and concerns of the HCWs are identified, and remote PFA is applied accordingly. |

| 5. Care: Provide Practical Assistance | HCWs with severe psychological and social needs are referred to relevant experts. |

| 6. Connection with Social Supports | HCWs receive continuous support from colleagues and employers without being stigmatized or discriminated. |

| 7. Information on Coping | HCWs are able to develop positive coping skills which allow adaptive functioning and return to baseline occupational functioning. |

| 8. Linkage with Collaborative Services | HCWs are empowered to seek further assistance from other relevant agencies such as non-governmental organizations in the community for the continuity of care. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sulaiman, A.H.; Ahmad Sabki, Z.; Jaafa, M.J.; Francis, B.; Razali, K.A.; Juares Rizal, A.; Mokhtar, N.H.; Juhari, J.A.; Zainal, S.; Ng, C.G. Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital, Malaysia. Healthcare 2020, 8, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030228

Sulaiman AH, Ahmad Sabki Z, Jaafa MJ, Francis B, Razali KA, Juares Rizal A, Mokhtar NH, Juhari JA, Zainal S, Ng CG. Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital, Malaysia. Healthcare. 2020; 8(3):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030228

Chicago/Turabian StyleSulaiman, Ahmad Hatim, Zuraida Ahmad Sabki, Mohd Johari Jaafa, Benedict Francis, Khairul Arif Razali, Aliaa Juares Rizal, Nor Hazwani Mokhtar, Johan Arif Juhari, Suhaila Zainal, and Chong Guan Ng. 2020. "Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital, Malaysia" Healthcare 8, no. 3: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030228

APA StyleSulaiman, A. H., Ahmad Sabki, Z., Jaafa, M. J., Francis, B., Razali, K. A., Juares Rizal, A., Mokhtar, N. H., Juhari, J. A., Zainal, S., & Ng, C. G. (2020). Development of a Remote Psychological First Aid Protocol for Healthcare Workers Following the COVID-19 Pandemic in a University Teaching Hospital, Malaysia. Healthcare, 8(3), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030228