Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice: An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Best Practice Spotlight Organization (BPSO®) Program

1.2. The BPSO Program in Australia

- Establishing dynamic, long-term partnerships (international and local) that focus on patient care via knowledge-based nursing/midwifery practice;

- Identification of effective strategies for system-wide disseminating of best practice guidelines (BPG) implementation;

- Demonstrate creative strategies for successfully implementing nursing and midwifery best practice guidelines (BPGs) at both individual and organizational levels;

- Inaugurate effective evaluation protocols using structural, process and outcome indicators;

- Ensure sustainability and long-term integration of the program by creating attitudinal change among staff and therefore positively changing the culture of the organization.

1.3. Evaluation of the Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of the Research

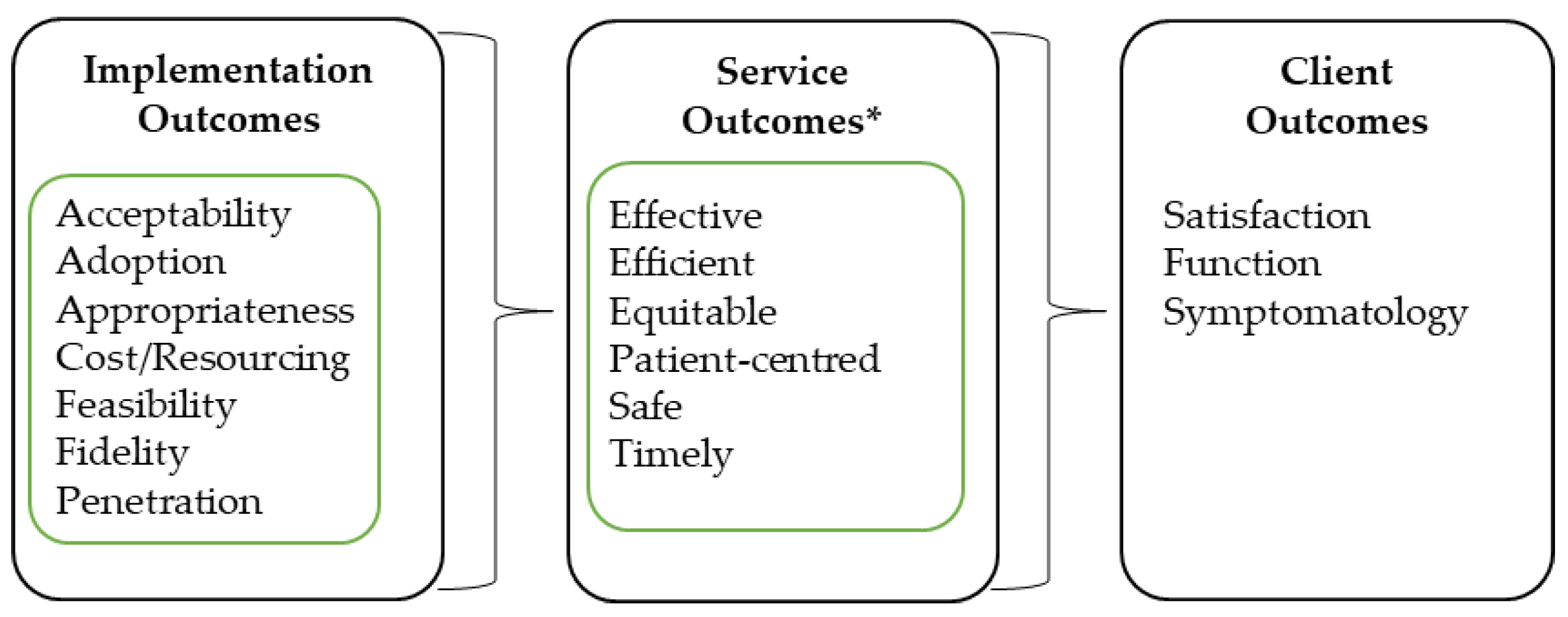

2.2. Conceptual Framework

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection Tools

2.4.1. Routinely Collected BPSO Program Evaluation and Reporting Data

2.4.2. Review of Key Documentation

2.4.3. Interviews and Focus Groups

2.4.4. Questionnaire

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.1.1. Interview Participants

3.1.2. Focus Group Participants

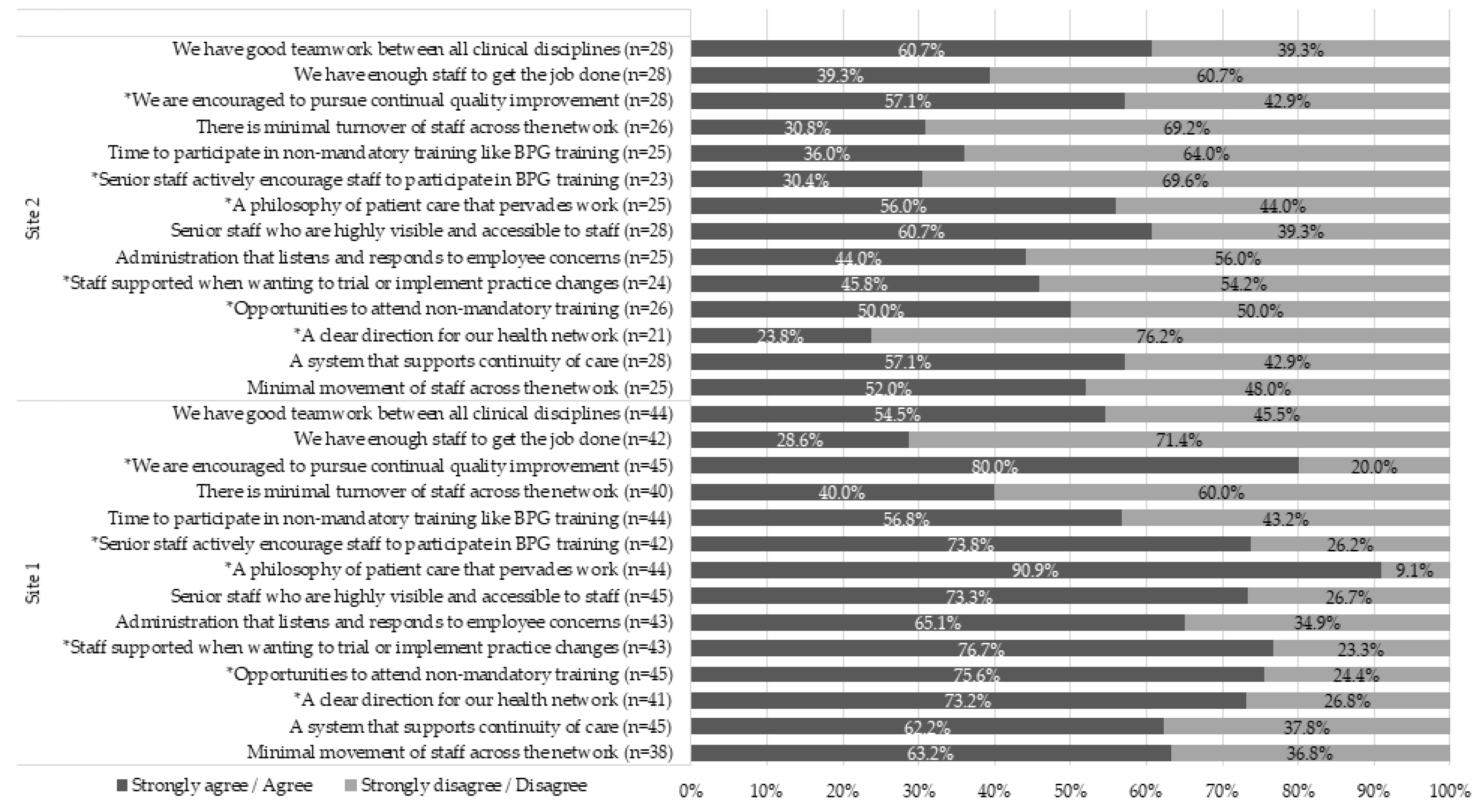

3.1.3. Questionnaire Participants

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators to Effective Implementation of the BPSO Program in a Complex Health Care System

3.3. Impact on Service Delivery of the BPSO Program

4. Discussion

4.1. Facilitators and Barriers to Implementation and Impact on Service Delivery

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.3. Implications for Implementation Evaluation

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. The 2017 Update, Global Health Workforce Statistics; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government Department of Health. Health Workforce Data. 2017. Available online: https://hwd.health.gov.au/summary.html (accessed on 30 August 2019).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Nursing and Midwifery Workforce 2015; Cat. No. WEB 141; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Crettenden, I.F.; McCarty, M.V.; Fenech, B.J.; Heywood, T.; Taitz, M.C.; Tudman, S. How evidence-based workforce planning in Australia is informing policy development in the retention and distribution of the health workforce. Hum. Resour. Health 2014, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards, 2nd ed.; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, T.; Bennett, S.; del Mar, C. Evidence-Based Practice across the Health Professions-E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, S.E.; Glasziou, P.; Richardson, W.S.; Haynes, R.B. Evidence-Based Medicine E-Book: How to Practice and Teach EBM; Elsevier Health Sciences: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Gallagher-Ford, L.; Zellefrow, C.; Tucker, S.; Thomas, B.; Sinnott, L.T.; Tan, A. The first US study on nurses’ evidence-based practice competencies indicates major deficits that threaten healthcare quality, safety, and patient outcomes. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2018, 15, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, H.; Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. The state of readiness for evidence-based practice among nurses: An. integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 56, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Perillo, S.; Brown, T. What are the factors of organisational culture in health care settings that act as barriers to the implementation of evidence-based practice? A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e34–e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, K.S.; Davies, B.; Ploeg, J. Sustaining guideline implementation: A multisite perspective on activities, challenges and supports. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 4413–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bick, D.; Graham, I.D. Evaluating the Impact of Implementing Evidence-Based Practice; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Gallagher-Ford, L.; Long, L.E.; Fineout-Overholt, E. The establishment of evidence-based practice competencies for practicing registered nurses and advanced practice nurses in real-world clinical settings: Proficiencies to improve healthcare quality, reliability, patient outcomes, and costs. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2014, 11, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grol, R.; Dalhuijsen, J.; Thomas, S.; Rutten, G.; Mokkink, H. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: Observational study. Bmj 1998, 317, 858–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Best Practice Spotlight Organizations 2018. Available online: http://rnao.ca/bpg/bpso (accessed on 20 November 2018).

- Grinspun, D.; Virani, T.; Bajnok, I. Nursing best practice guidelines: The RNAO project. Hosp. Q. 2001, 4, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploeg, J.; Skelly, J.; Rowan, M.; Edwards, N.; Davies, B.; Grinspun, D.; Bajnok, R.N.I.; Downey, A. The role of nursing best practice champions in diffusing practice guidelines: A mixed methods study. Worldviews Evid. Based Nurs. 2010, 7, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virani, T.; Grinspun, D. RNAO’s best practice guidelines program: Progress report on a phenomenal journey. Adv. Ski. Wound Care 2007, 20, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchanan, D.; Fitzgerald, L.; Ketley, D.; Gollop, R.; Jones, J.L.; Lamont, S.S.; Neath, A.; Whitby, E. No going back: A review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2005, 7, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, D.A.; Fitzgerald, L.; Ketley, D. The Sustainability and Spread of Organizational Change: Modernizing Healthcare; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Robert, G.; Macfarlane, F.; Bate, P.; Kyriakidou, O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004, 82, 581–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; Griffey, R.; Hensley, M. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.K.; Landsverk, J.; Aarons, G.; Chambers, D.; Glisson, C.; Mittman, B. Implementation research in mental health services: An emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2009, 36, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; Institute of Medicine Staff. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbooks in Psychology; Cooper, H., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, L.; Athanasiou, T.; Russ, S. Implementation science: A neglected opportunity to accelerate improvements in the safety and quality of surgical care. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 1104–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokke, K.; Olsen, N.R.; Espehaug, B.; Nortvedt, M.W. Evidence based practice beliefs and implementation among nurses: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2014, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. Person-and Family-Centred Care; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grinspun, D.; Bajnok, I. Transforming Nursing through Knowledge; Sigma Theta Tau: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Keeping Patients Safe: Institute of Medicine Looks at Transforming Nurses’ Work Environment; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B.; Edwards, N.; Ploeg, J.; Virani, T. Insights about the process and impact of implementing nursing guidelines on delivery of care in hospitals and community settings. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, K.S.; Downey, A.; Davies, B.; Bajnok, I.; Waggott, M. Using the NHS sustainability framework to understand the activities and resource implications of Canadian nursing guideline early adopters. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twigg, D.E.; Pugh, J.D.; Gelder, L.; Myers, H. Foundations of a nursing-sensitive outcome indicator suite for monitoring public patient safety in Western Australia. Collegian 2016, 23, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, D.E.; Duffield, C.; Evans, G. The critical role of nurses to the successful implementation of the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. Aust. Health Rev. 2013, 37, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Headline | Site 1 | Site 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Patient population | Women and Children under 18 years | People living with mental health issues |

| BPSO pre-designate period | March 2016–March 2019 | March 2016–March 2019 |

| BPGs selected for the site (in order of implementation) | Person and Family Centered Care (PFCC) Care transitions Woman’s abuse | Alternative approaches to the use of restraint Assessment and care of adults at risk for suicidal ideation and behavior PFCC |

| Stakeholder Group | Invited for Interview | Interviewed | Focus Group Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Site 2 | 6 | 5 | 4 |

| Host organization for the BPSO | 3 | 2 | NA |

| Office of Chief Nurse/Midwife | 1 | 0 | NA |

| Implementation Outcome Domain | Facilitators with Respect to the Implementation Outcome Domain | Barriers with Respect to the Implementation Outcome Domain |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | Acceptability was positively impacted by: • BPGs being context independent, which made their adoption flexible and adaptable to the system context • Conducting training surveys to understand how participants perceived the training and modifying or course-correcting where required | Acceptability was negatively impacted by: • The language of the BPSO program, which added new terms and acronyms to learn in an environment that was already flooded. • Differing levels of “buy-in” from the executive leadership. • Disrupted leadership at multiple levels, which had the potential to disrupt the program implementation. • Complexity and sensitivity of the topic (e.g., woman’s abuse), which required extensive consultation and negotiation prior to roll-out. |

| Adoption | Adoption was positively impacted by: • Having staff and consumer representation throughout the program. Consumer representation was noted as a strong facilitator in this aspect. • Monitoring and benchmarking progress of the program KPIs. • Having Champions training targets, with a strategy to meet the target. | Adoption was negatively impacted by: • The BPSO program being nursing-driven and therefore not perceived as having multidisciplinary application, which made it difficult to engage with other clinicians. • Poor documentation and/or tracking of progress and KPIs including Champions training targets. • Time required in planning a BPG meant that the roll-out time (e.g., time to train sufficient number of Champions) was limited. |

| Appropriateness | Appropriateness was positively impacted by: • Choosing the correct BPGs to align with the strategic directions of the organization • Having a communication plan to support the BPSO program and including it in induction and education allowed staff to understand how it benefited the organization, their roles and their patients/clients | Appropriateness was negatively impacted by: • Lack of promotion and visibility of trained champions, the work they do, how it stemmed from the BPSO program and of the BPSO program as a whole, which affected people’s perceptions of whether it was useful, important or necessary endeavor to support. |

| Cost/resources | Cost/resources was positively impacted by: • Externally sourced funding attached a budget line to the program and protected the core requirements to deliver on the program. • Utilizing internal resourcing, partnerships, and activities to optimize efficient delivery of the program within the local context. • Having initial resources to fund the program, which was perceived as essential for its viability and legitimacy. | Cost/resources was negatively impacted by: • Lack of inflexibility to internal annual accounting requirements (end of financial year acquittal), which placed unnecessary levels of budget planning and negotiation to justify use of resources across the three years, so as not to lose the committed funds. |

| Feasibility | Feasibility was positively impacted by: • Having the organization in a position with clear strategies as to where it was heading and knowing how the guidelines would fit with the strategies. • Having organizational executive leadership and support, a designated BPSO site lead, and the Australian host (ANMF (SA Branch)) support (all perceived as critical elements). | Feasibility was negatively impacted by: • Releasing staff for champions training. This may have been as a result of timing of training sessions or reported as a result of insufficient backfill or staff levels on the day. This had implications for achieving 15% coverage across all areas. • Mixed levels of support and uptake of the program including champions training by executive, clinical staff, and consumer input. • High levels of staff and management turnover (churn), and challenges with overall staffing numbers. |

| Fidelity | Fidelity was positively impacted by: • The relatively prescribed approach of the BPSO program and its KPIs. Examples of fidelity measures include: establishment of the BPSO steering committee; identification of non-compliance with evidence based best practice (gap analysis); utilization of BPGs to inform practice, training and recruitment of Champions; and BPG implementation reporting and evaluation (action plan). | Fidelity was negatively impacted by: • Having ‘noise’ of other training programs or other initiatives that were very similar to the objectives of the selected BPGs, which then made it difficult for site leads to either work with those other initiatives to align the training with the BPG and meet their KPIs • Poor maintenance and lack of commitment of expected tasks associated with the BPSO program impacted on the quality of much of the planning work required for successful execution. |

| Penetration | Penetration was positively impacted by: • Having an executive sponsor for the program. This was noted as critical because executive support was critical to reminding people of the program and keeps it on the organization’s agenda at a broad level. • Having a BPSO program KPI of engaging a critical mass of 15% of nursing and midwifery staff in clinical settings as champions where guidelines are being implemented. • Establishing a champions and super champions network with meetings occurring monthly and quarterly, respectively. | Penetration was negatively impacted by: • Turnover and movement of staff within the network, which meant that trained Champions were lost and therefore impacted momentum and consistency, as well as BPSO KPIs. • Maintaining an active network of champions or super champions. |

| Sustainability | Sustainability was positively impacted by: • Establishing the right governance and BPSO steering committee membership, which was perceived to also ensure long-term sustainability beyond the pre-designate period. • Situating the BPSO program within a clinical unit that is agile, guided by transformational leadership, has capacity to provide long-term commitment to the program and can serve as program ambassadors. • Having a sustainability plan inclusive of strategies related to maintenance, program growth, risk management, embedding BPSO related work into everyday practice, and aligning the program’s KPIs with those of the organization. | Sustainability was negatively impacted by: • Turnover in executive and senior staff impacted on continuity of commitment and championing of the program at executive level discussion. • Not having a sustainability plan with a component focused on embedding and aligning the work with everyday practice. • Not aligning BPSO program KPIs to organizational KPIs related to safety and quality, education or practice improvement. |

| Service Outcome Domain | Notes on Impact on Service Outcome |

|---|---|

| Effective | • Effectiveness of the program was assessed against the BPGs and the affiliated studies and audits. Their use in practice was demonstrated in practice changes such as the Person Centered KPI Project (various wards), woman screening, consumer feedback survey, and care transitions bedside handover consumer survey. • BPSO nursing indicators were well-defined for readily measurable clinical events such as falls or restraint usage, however for some BPGs there were no measurable indicators to report against; consequently, these had to be defined and worked out by the site. |

| Efficient | • Facilitator of efficiency was inferred from the strategic selection of BPGs that aligned with relevant works and committees such as the NSQHS standards and Consumer and Community Engagement Strategy. • Progress and performance reporting and the data systems used were not lean and involved various data collection methods, duplicative data entry, and support from multiple stakeholders to provide the necessary data. • Efficiency through cost saving associated with initiatives associated with the BPSO program were reported. For example, the chaperone program has reduced reliance on agency and security guard use, both of which are a more expensive workforce to maintain. |

| Equitable | • There was a deliberate approach reported to ensure equity across the program and the three BPGs. Examples of activities included: stakeholder engagement across culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) people, migrant health service and aboriginal health service, and health literacy work capacity building through workshops/online courses specifically designed for Aboriginal persons, i.e., Understanding and Managing Risk: Domestic and Aboriginal Family Violence Training 1st July 2016, Aboriginal Cultural Learning online course, Kaurna Cultural Tour, and Champions workshop with the Aboriginal Educator Development officer. Demonstration of stakeholder assessments for BPGs, i.e., CALD People; migrant health service and aboriginal health service. • Some initiatives implemented as part of the BPSO program may be inherently addressing equity of care. For example, the Maastricht interview training program reported as part of the PFCC BPG may be building staff capacity to engage with, and subsequently provide better care to, people who have auditory hallucinations. |

| Patient-centered | • Patient-centeredness was a core component of the three BPGs selected. The Consumer and Community engagement team were actively involved in all aspects of the PFCC BPG; from governance to workshop participation, to evaluation activities. Key projects included the Person Centered KPI Project and initiatives such as Shared Decision Making, the Health Literacy Fact sheet series, and Consumer Input and Feedback. Engagement and partnership across the network occurred at all levels with the Consumer and Community Engagement Division. • Consumer co-delivery of workshops, preparing and reviewing literature, involvement in designing, and evaluating data and engaging in multi-disciplinary conversation around how to improve the program was noted as a strength of the program. • Training and education around the Champion training included reflective exercises for staff that has been meaningful as documented in workshop evaluations. There were shifts, because of the BPSO program, around the way staff work with consumers especially around choice, option talk, and decision making. The BPSO program encouraged choice- and decision- based conversations with patients/clients, which was a deliverable for the PFCC BPG within the organization. |

| Safe | • BPG activities have been designed to align to safety and quality initiatives that meet the NSQHS standards. • A key element of the BPG Care Transitions and Woman Abuse has been safety. Integrating safety into these BPGs has included working with and actioning various activities through relevant committees. Training and resources generated have reflected the input of these committees regarding safety and quality. • One of the eight KPIs in the Person Centered KPI project was: Patient’s sense of safety whilst under the care of the nurse/midwife and was assessed by asking patients and observed practice. This outcome was approximately 90% (always) across five wards and 75% (always), and 18% (most of the time), for the other ward. Over the 2–3-year auditing cycle there was demonstrable improvements across several of the KPIs. • Training and funded projects under the suicide prevention BPG and alternative use of restraints BPG were centered around client safety, as well as person-centered care and human rights. |

| Timely | • An example of timeliness related to the care transitions BPG at Site 1. Identified gaps in practice and changes addressed as part of this BPG include; timeframe for handover, enabling timely discharge, and the development of the General Practice Liaison Unit (GPLU), which was developed to address communication from hospital to doctors in the community. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharplin, G.; Adelson, P.; Kennedy, K.; Williams, N.; Hewlett, R.; Wood, J.; Bonner, R.; Dabars, E.; Eckert, M. Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice: An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context. Healthcare 2019, 7, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040142

Sharplin G, Adelson P, Kennedy K, Williams N, Hewlett R, Wood J, Bonner R, Dabars E, Eckert M. Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice: An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context. Healthcare. 2019; 7(4):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040142

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharplin, Greg, Pam Adelson, Kate Kennedy, Nicola Williams, Roslyn Hewlett, Jackie Wood, Rob Bonner, Elizabeth Dabars, and Marion Eckert. 2019. "Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice: An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context" Healthcare 7, no. 4: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040142

APA StyleSharplin, G., Adelson, P., Kennedy, K., Williams, N., Hewlett, R., Wood, J., Bonner, R., Dabars, E., & Eckert, M. (2019). Establishing and Sustaining a Culture of Evidence-Based Practice: An Evaluation of Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing the Best Practice Spotlight Organization Program in the Australian Healthcare Context. Healthcare, 7(4), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7040142