Clinical Use of an Order Protocol for Distress in Pediatric Palliative Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Details of the OPD

2.2. Outcomes

2.3. Data Management

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

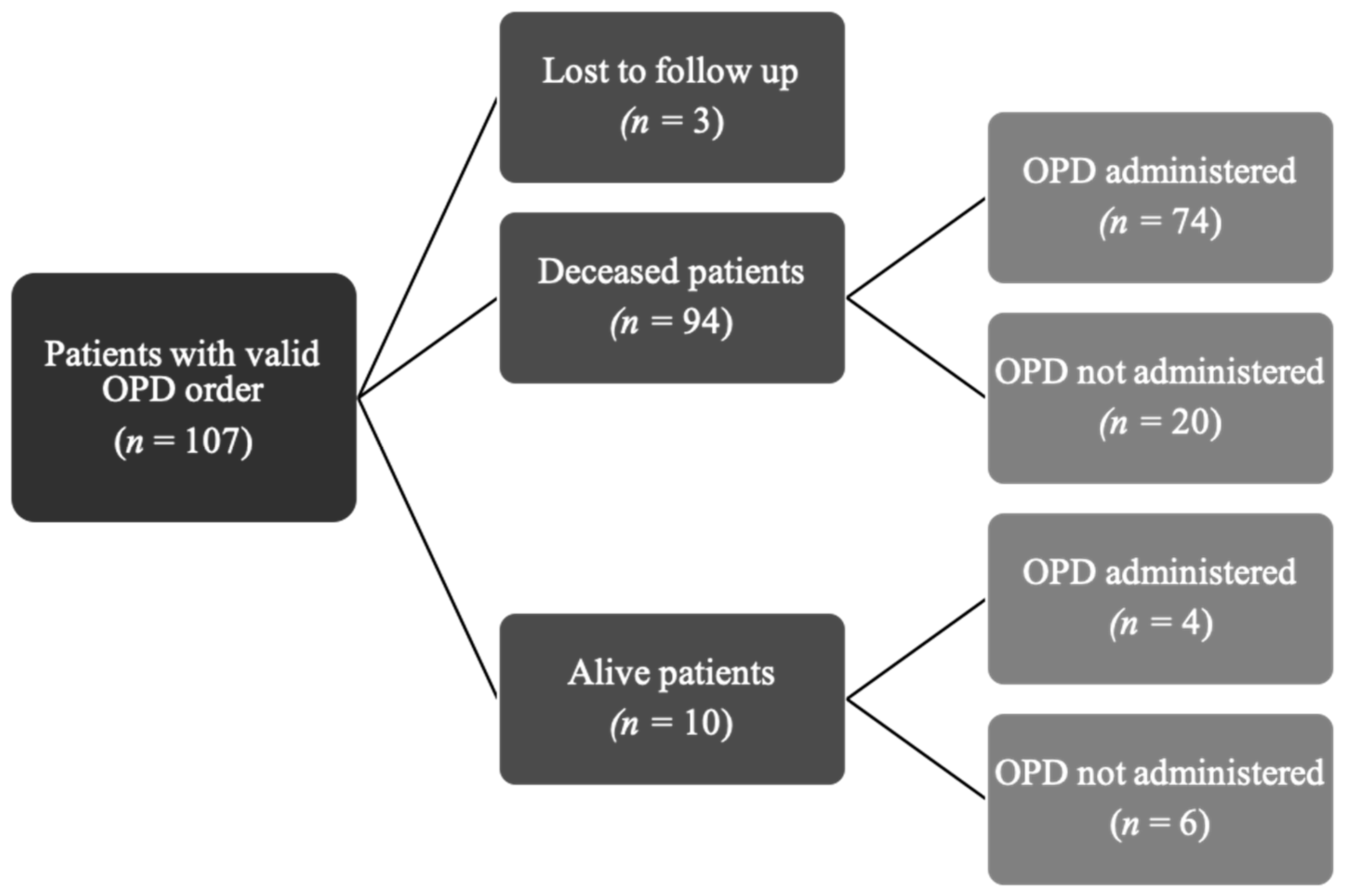

3.1. Patients’ Characteristics

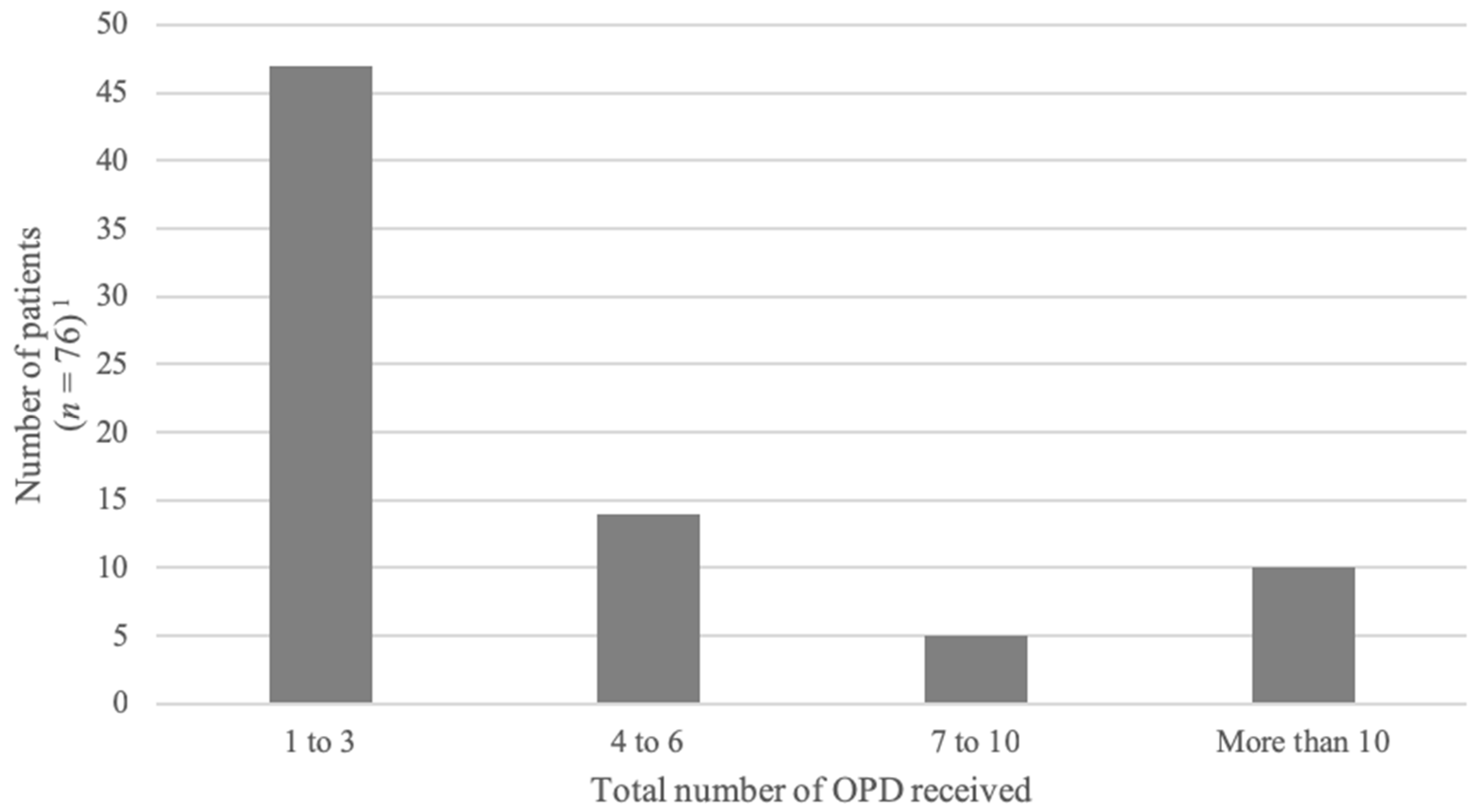

3.2. OPD Characteristics and Administration

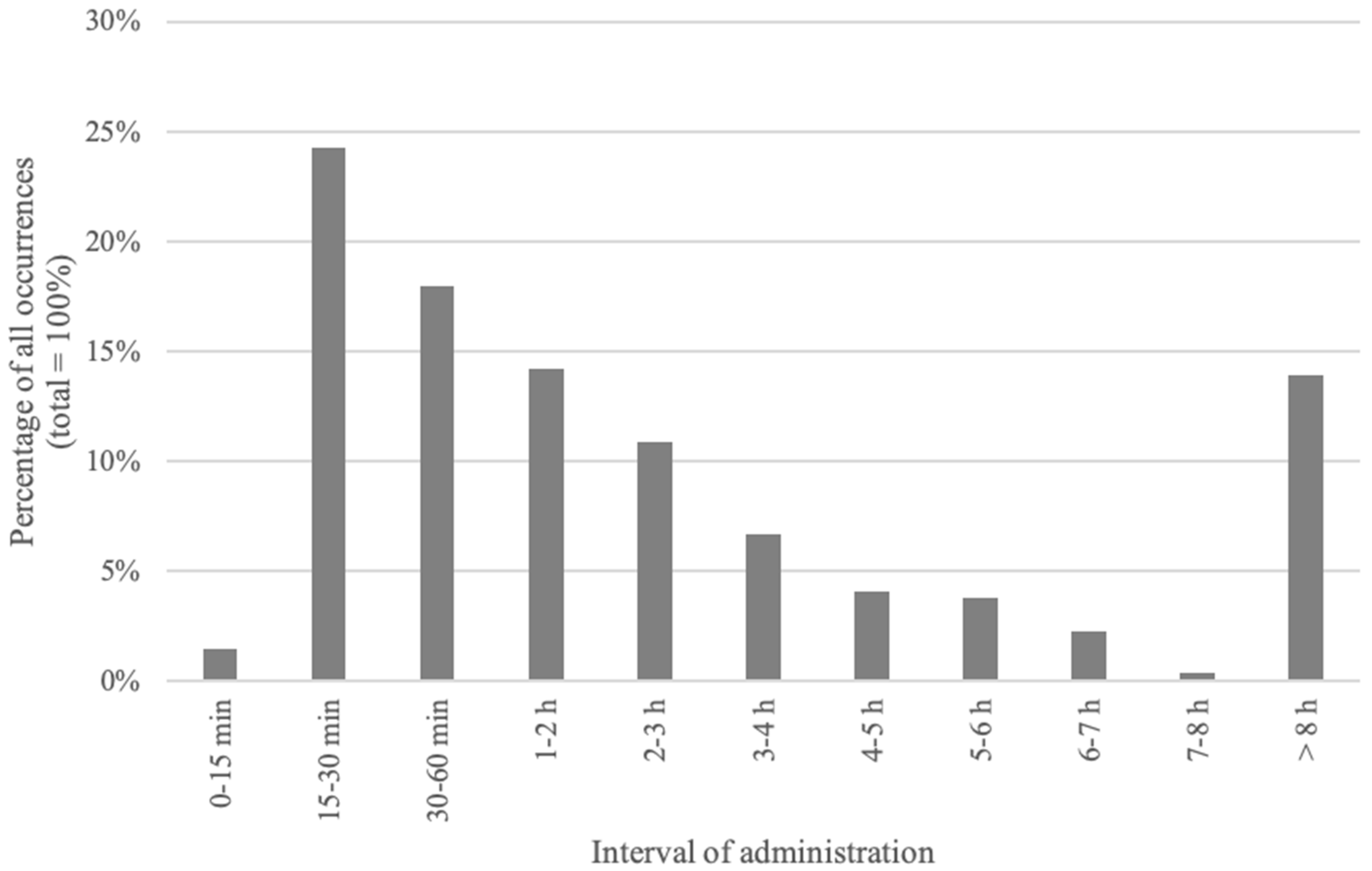

3.3. Intervals

3.4. Effectiveness of the OPD for Symptom Management

3.5. Safety of OPD Administration

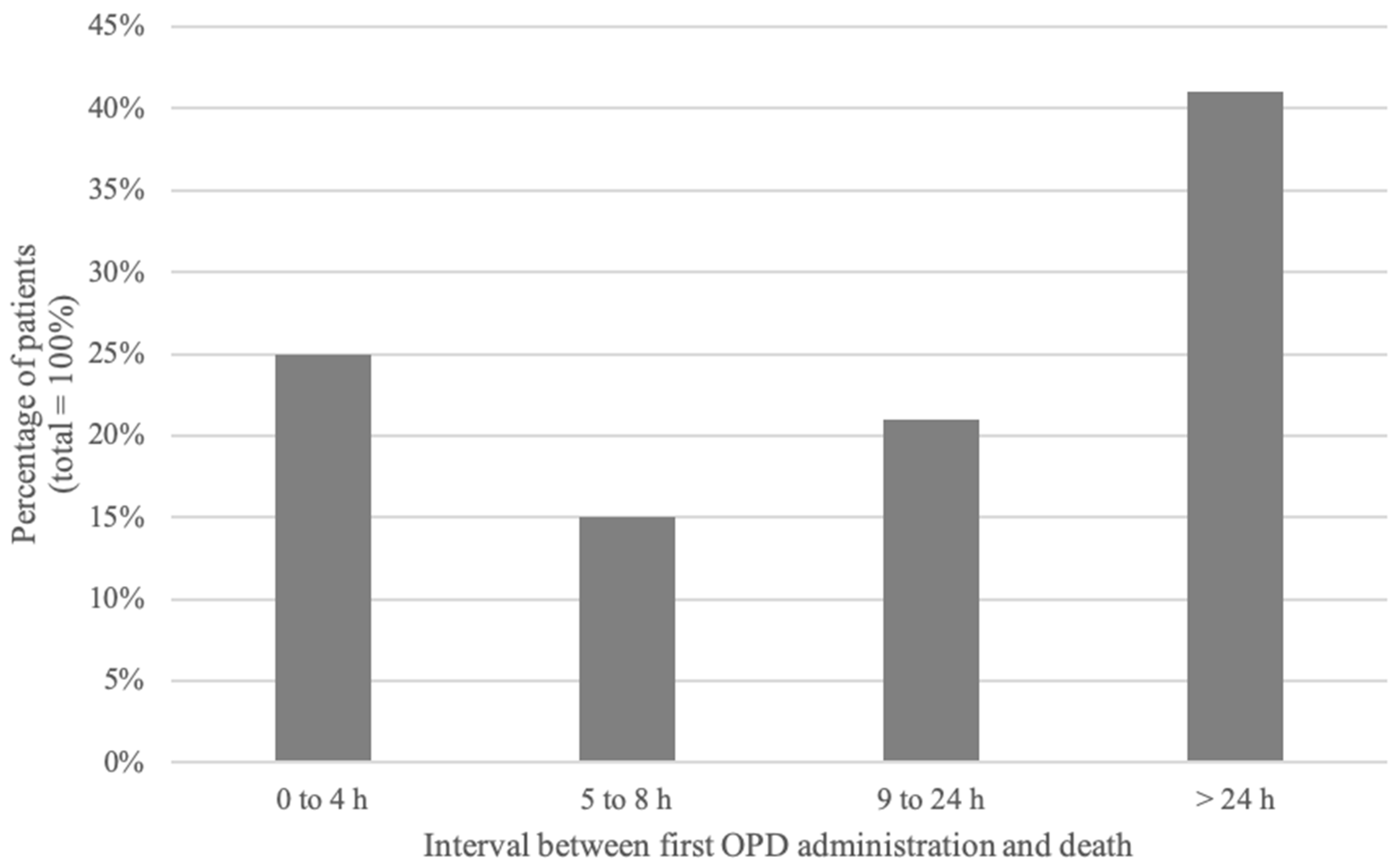

3.5.1. Interval between OPD Administration and Death

3.5.2. Clinical Evolution after OPD Administration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolfe, J.; Grier, H.E.; Klar, N.; Levin, S.B.; Ellenbogen, J.M.; Salem-Schatz, S.; Emanuel, E.J.; Weeks, J.C. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drake, R.; Frost, J.; Collins, J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2003, 26, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.; Burghen, E.; Srivastava, D.K.; Okuma, J.; Anderson, L.; Powell, B.; Furman, W.L.; Hinds, P.S. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e1301–e1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, R.; Siden, H.; Cadell, S.; Davies, B.; Andrews, G.; Feichtinger, L.; Singh, M. Charting the territory: Symptoms and functional assessment in children with progressive, non-curable conditions. Arch. Dis. Child. 2014, 99, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himelstein, B.P.; Hilden, J.M.; Boldt, A.M.; Weissman, D. Pediatric palliative care. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1752–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, R.; Bosma, H.; Johnston, M.F.; Cadell, S.; Davies, B.; Siden, H.; Straatman, L. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care: A Delphi study. J. Palliat. Care 2008, 24, 229–239. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J.N.; Levine, D.R.; Hinds, P.S.; Weaver, M.S.; Cunningham, M.J.; Johnson, L.; Anghelescu, D.; Mandrell, D.; Gibson, D.V.; Jones, B.; et al. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlahan, K.E.; Branowicki, P.A.; Mack, J.W.; Dinning, C.; McCabe, M. Can end of life care for the pediatric patient suffering with escalating and intractable symptoms be improved? J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 2006, 23, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.M. Palliation of dyspnea in pediatrics. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2012, 9, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorman, S.; Byrne, A.; Edwards, A. Which measurement scales should we use to measure breathlessness in palliative care? A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.A.; Clarke, N.E.; Donath, S.M.; McCarthy, M.; Anderson, V.A.; Wolfe, J. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer: An Australian perspective. Med. J. Aust. 2010, 192, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Namisango, E.; Bristowe, K.; Allsop, M.J.; Murtagh, F.E.M.; Abas, M.; Higginson, I.J.; Downing, J.; Harding, R. Symptoms and concerns among children and young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions: A systematic review highlighting meaningful health outcomes. Patient 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, K.A.; Nachreiner, D.; Patel, J.; Mayo, R.L.; Kearney, C.D. Impact of standardized palliative care order set on end-of-life care in a community teaching hospital. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, A.M.; Brown-Saltzman, K.; Barry, T.; Quan, R.J.; Wenger, N.S. Assessment of implementation of an order protocol for end-of-life symptom management. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bender, M.A.; Hurd, C.; Solvang, N.; Colagrossi, K.; Matsuwaka, D.; Curtis, J.R. A new generation of comfort care order sets: Aligning protocols with current principles. J. Palliat. Med. 2017, 20, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morita, T.; Tsunoda, J.; Inoue, S.; Chihara, S. Effects of high dose opioids and sedatives on survival in terminally ill cancer patients. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2001, 21, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navigante, A.H.; Cerchietti, L.C.; Castro, M.A.; Lutteral, M.A.; Cabalar, M.E. Midazolam as adjunct therapy to morphine in the alleviation of severe dyspnea perception in patients with advanced cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2006, 31, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercovitch, M.; Adunsky, A. Patterns of high-dose morphine use in a home-care hospice service: Should we be afraid of it? Cancer 2004, 101, 1473–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, K.E.; Quednau, I.; Klaschik, E. Is there a higher risk of respiratory depression in opioid-naive palliative care patients during symptomatic therapy of dyspnea with strong opioids? J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidet, G.; Daoust, L.; Duval, M.; Ducruet, T.; Toledano, B.; Humbert, N.; Gauvin, F. An order protocol for respiratory distress/acute pain crisis in pediatric palliative care patients: Medical and nursing staff perceptions. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walling, A.M.; Ettner, S.L.; Barry, T.; Yamamoto, M.C.; Wenger, N.S. Missed opportunities: Use of an end-of-life symptom management order protocol among inpatients dying expected deaths. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| OPD | Details |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | The OPD is recommended by the palliative care team when judged appropriate if (a) there is a possibility of respiratory distress, acute pain crisis or anxiety, and (b) resuscitation status has been discussed and excludes the use of chest compressions, defibrillation and endotracheal intubation in the setting of clinical worsening or cardiopulmonary arrest. |

| Discussion with family | There is a discussion between the physician and the patient’s parents (and patient when appropriate) to explain the OPD (indication, medication used, anticipated effects). The OPD is prescribed if parents (and patient when appropriate) agree with the protocol. |

| Prescription | After agreement from the family, OPD medications are prescribed by a physician according to recommended doses. OPD consists of (1) midazolam (0.1 mg/kg if naive or 0.15 mg/kg if already on benzodiazepines), with (2) morphine (0.1 mg/kg if naive or 10% to 20% of daily morphine dose) or hydromorphone (0.02 mg/kg if naive or 10% to 20% of daily dose), with or without (3) glycopyrrolate (0.004 mg/kg) or scopolamine (0.006 mg/kg). Prefilled syringes are kept in a locked cabinet on the care unit accessible by the patient’s bedside nurse. |

| OPD initiation | The bedside nurse can initiate the OPD whenever the patient presents severe respiratory distress, acute pain or anxiety that is not relieved by usual measures; the nurse must notify the physician as soon as the OPD is initiated. The medication is administered only if parents (or the patient when appropriate) agree with the use of the protocol. If the parents refuse, the nurse notifies the physician and waits before the initiating the OPD; all other relevant medication or comfort measures are maintained. |

| Evaluation by the physician | Physicians are required to come to the patient’s bedside whenever the OPD is initiated to evaluate the cause of distress, adjust medication and provide support to the patient and family. |

| Repetition of the OPD | Nurses can repeat administration of the OPD every 15 min and up to two times, as necessary, until the physician arrives at the bedside. |

| Out of hospital providers | The medication can be used at home by community nurses or by parents (after evaluation and training by the palliative care team). Medications can be prepared by the hospital pharmacist or the patient’s local pharmacist. They are stored in a separate kit at home in prefilled, labeled syringes with a guide for utilization (to minimize dosing or administration errors). |

| Variables | Characteristics | Number of Patients (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 45 (43) |

| Female | 59 (57) | |

| Diagnosis | Cancer | 50 (48) |

| Cerebral tumor | 17 (16) | |

| Leukemia/lymphoma | 12 (12) | |

| Bone/muscle/tissue tumor | 14 (13) | |

| Neuroblastoma | 4 (4) | |

| Wilms/liver tumor | 3 (3) | |

| Neurologic disorders | 29 (28) | |

| Encephalopathy (incl. anoxic brain injury and seizure disorders) | 24 (23) | |

| Spinal muscular atrophy type 1 | 5 (5) | |

| Genetic disorders | 11 (11) | |

| Congenital syndrome | 9 (9) | |

| Inborn errors of metabolism | 2 (2) | |

| Cardiac disease | 9 (9) | |

| Congenital cardiopathy | 7 (7) | |

| Others | 2 (2) | |

| Pulmonary disease | 3 (3) | |

| Others | 2 (2) |

| Medication | Dose mg/kg Median (Range) | Number of OPD (%) |

| Benzodiazepine | ||

| Midazolam | 0.1 (0.03–0.4) | 344 (98) |

| Opioid | ||

| Morphine | 0.1 (0.04–0.6) | 261 (75) |

| Hydromorphone | 0.1 (0.02–0.35) | 83 (24) |

| Anticholinergic agent | ||

| Glycopyrrolate | 0.004 (0.003–0.005) | 89 (25) |

| Scopolamine | 0.006 (0.002–0.008) | 23 (7) |

| Place of ODP administration | Number of OPD (%) | |

| Sainte-Justine Hospital | 239 (68) | |

| Lighthouse Hospice | 74 (21) | |

| Marie-Enfant Rehabilitation Center | 25 (7) | |

| Home | 12 (3) | |

| Route of administration | Number of OPD (%) | |

| Subcutaneous | 184 (53) | |

| Intravenous | 166 (47) | |

| Person who administrated the OPD | Number of OPD (%) | |

| Nurse | 261 (75) | |

| Attending physician | 57 (16) | |

| Resident | 21 (6) | |

| Parents | 10 (3) | |

| Other—not specified | 1 (0.3) | |

| Indication stated for administration | Number of OPD (%) | |

| Respiratory distress | 310 (89) | |

| Pain crisis | 29 (8) | |

| Anxiety | 4 (1) | |

| Other | 4 (1) | |

| Unknown | 3 (1) | |

| Relief | Number of Episodes (%) |

|---|---|

| Relief and partial relief | 245 (90) |

| Effective relief | 185 (68) |

| Partial relief | 60 (22) |

| No relief | 28 (10) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marquis, M.-A.; Daoust, L.; Villeneuve, E.; Ducruet, T.; Humbert, N.; Gauvin, F. Clinical Use of an Order Protocol for Distress in Pediatric Palliative Care. Healthcare 2019, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010003

Marquis M-A, Daoust L, Villeneuve E, Ducruet T, Humbert N, Gauvin F. Clinical Use of an Order Protocol for Distress in Pediatric Palliative Care. Healthcare. 2019; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarquis, Marc-Antoine, Lysanne Daoust, Edith Villeneuve, Thierry Ducruet, Nago Humbert, and France Gauvin. 2019. "Clinical Use of an Order Protocol for Distress in Pediatric Palliative Care" Healthcare 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010003

APA StyleMarquis, M.-A., Daoust, L., Villeneuve, E., Ducruet, T., Humbert, N., & Gauvin, F. (2019). Clinical Use of an Order Protocol for Distress in Pediatric Palliative Care. Healthcare, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare7010003