Inflammation-Related Parameters in Lung Cancer Patients Followed in the Intensive Care Unit

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Patients and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent for Publication

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diem, S.; Schmid, S.; Krapf, M.; Flatz, L.; Born, D.; Jochum, W.; Templeton, A.J.; Früh, M. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer 2017, 111, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandaliya, H.; Jones, M.; Oldmeadow, C.; Nordman, I.I.C. Prognostic biomarkers in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NLR), lymphocyte to monocyte ratio (LMR), platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI). Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2019, 8, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Cancer Control Status and APACHE II Score Are Prognostic Factors for Critically Ill Patients with Cancer and Sepsis—ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929664618305965 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Lin, Y.-C.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Huang, C.-C.; Hsu, K.-H.; Wang, S.-W.; Tsao, T.C.-Y.; Lin, M.-C. Outcome of lung cancer patients with acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Respir. Med. 2004, 98, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussat, S.; El’Rini, T.; Dubiez, A.; Depierre, A.; Barale, F.; Capellier, G. Predictive factors of death in primary lung cancer patients on admission to the intensive care unit. Intensiv. Care Med. 2000, 26, 1811–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, J.; Kervarrec, T.; Touzé, A.; Avenel-Audran, M.; Beneton, N.; Esteve, E.; Hainaut, E.W.; Aubin, F.; Machet, L.; Samimi, M. A high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a potential marker of mortality in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: A retrospective study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, 712–721.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prognostic Role of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio in Solid Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/jnci/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/jnci/dju124 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Hu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W. Clinical utility of the modified Glasgow prognostic score in lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, J.-H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Q.-Q.; Zhang, K.-P.; Tang, M.; Ge, Y.-Z.; Li, W.; Xu, H.-X.; Guo, Z.-Q.; et al. Relationship Between Prognostic Nutritional Index and Mortality in Overweight or Obese Patients with Cancer: A Multicenter Observational Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 3921–3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.; Fontes, F.; Dantas, J.; Gadelha, D.; Cariello, P.; Nardes, F.; Amorim, C.; Toscano, L.; Rocco, J.R. Performance of six severity-of-illness scores in cancer patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit: A prospective observational study. Crit. Care 2004, 8, R194–R203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winther-Larsen, A.; Aggerholm-Pedersen, N.; Sandfeld-Paulsen, B. Inflammation-scores as prognostic markers of overall survival in lung cancer: A register-based study of 6210 Danish lung cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, L. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index in Patients with Cervical Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Luo, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, R.; Li, L.; Zhang, C. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia and prognosis in lung cancer patients after surgery: A retrospective study. Medicine 2021, 100, e25295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bao, J.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Jin, M.-X. Prognostic nutritional index as a prognostic factor in lung cancer patients receiving chemotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 5636–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitahara, H.; Shoji, F.; Akamine, T.; Kinoshita, F.; Haratake, N.; Takenaka, T.; Tagawa, T.; Sonoda, T.; Shimokawa, M.; Maehara, Y.; et al. Preoperative prognostic nutritional index level is associated with tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte status in patients with surgically resected lung squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2021, 60, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moemen, M.E. Prognostic categorization of intensive care septic patients. World J. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 1, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoring System for Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes and Its Prognostic Value for Gastric Cancer. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00071 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- The Role of the Systemic Inflammatory Response in Predicting Outcomes in Patients with Operable Cancer: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-16955-5 (accessed on 18 January 2022).

- Nøst, T.H.; Alcala, K.; Urbarova, I.; Byrne, K.S.; Guida, F.; Sandanger, T.M.; Johansson, M. Systemic inflammation markers and cancer incidence in the UK Biobank. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Horio, H.; Hato, T.; Harada, M.; Matsutani, N.; Morita, S.; Kawamura, M. Prognostic Significance of Preoperative Neutrophil–Lymphocyte Ratios in Patients with Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer After Complete Resection. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 1324–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahçeci, A.; Sedef, A.K.; Işik, D. The prognostic values of prognostic nutritional index in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2021, 33, e534–e540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréjak, C.; Terzi, N.; Thielen, S.; Bergot, E.; Zalcman, G.; Charbonneau, P.; Jounieaux, V. Admission of advanced lung cancer patients to intensive care unit: A retrospective study of 76 patients. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groeger, J.S.; Lemeshow, S.; Price, K.; Nierman, D.M.; White, P.; Klar, J.; Granovsky, S.; Horak, D.; Kish, S.K. Multicenter outcome study of cancer patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A probability of mortality model. J. Clin. Oncol. 1998, 16, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azoulay, E.; Moreau, D.; Alberti, C.; Leleu, G.; Adrie, C.; Barboteu, M.; Cottu, P.; Levy, V.; Le Gall, J.-R.; Schlemmer, B. Predictors of short-term mortality in critically ill patients with solid malignancies. Intensiv. Care Med. 2000, 26, 1817–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.; Darmon, M.; Salluh, J.I.; Ferreira, C.G.; Thiéry, G.; Schlemmer, B.; Spector, N.; Azoulay, É. Prognosis of Lung Cancer Patients with Life-Threatening Complications. Chest 2007, 131, 840–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.A.; Hayes, R.B.; Goparaju, C.; Reid, C.; Pass, H.I.; Ahn, J. The microbiome in lung cancer tissue and recurrence-free survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2019, 28, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.; Macía, I.; Navarro-Martin, A.; Déniz, C.; Rivas, F.; Ureña, A.; Masuet-Aumatell, C.; Moreno, C.; Nadal, E.; Escobar, I. Prognostic value of the preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio for survival after lung cancer surgery. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Ma, G.; Wu, Q.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio among Asian lung cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 110606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, D.; Xu, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-W.; Che, G.-W. Prognostic Value of Pretreatment Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Meta-Analysis. Oncol. Res. Treat. 2019, 42, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutandyo, N.; Jayusman, A.M.; Widjaja, L.; Dwijayanti, F.; Imelda, P.; Hanafi, A.R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as mortality predictor of advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with COVID-19 in Indonesia. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 3868–3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unal, D.; Eroglu, C.; Kurtul, N.; Oguz, A.; Tasdemir, A. Are Neutrophil/Lymphocyte and Platelet/Lymphocyte Rates in Patients with Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Associated with Treatment Response and Prognosis? Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 5237–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hu, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Q. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicted Overall Survival and Radiosensitivity in Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Future Oncol. 2020, 16, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Cai, S.; Zhang, F.; Shao, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tan, F.; Gao, S.; He, J. Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) is useful to predict survival outcomes in patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac. Cancer 2019, 10, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, P.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Che, G. Prognostic value of the pretreatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardi, R.; Santoni, M.; Rinaldi, S.; Bower, M.; Tiberi, M.; Morgese, F.; Caramanti, M.; Savini, A.; Ferrini, C.; Torniai, M.; et al. Pre-treatment systemic immune-inflammation represents a prognostic factor in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2019, 7, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osugi, J.; Muto, S.; Matsumura, Y.; Higuchi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Gotoh, M. Prognostic impact of the high-sensitivity modified Glasgow prognostic score in patients with resectable non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2016, 12, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grose, D.; Devereux, G.; Brown, L.; Jones, R.; Sharma, D.; Selby, C.; Morrison, D.S.; Docherty, K.; McIntosh, D.; McElhinney, P.; et al. Simple and Objective Prediction of Survival in Patients with Lung Cancer: Staging the Host Systemic Inflammatory Response. Lung Cancer Int. 2014, 2014, 731925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 229) | Exitus (n = 135) | Discharged (n = 94) | p | |

| Age | 66.17 ± 11.89 | 66.80 ± 12.20 | 65.27 ± 11.44 | 0.338 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 163 (71.18%) | 94 (69.63%) | 69 (73.40%) | 0.535 |

| Female | 66 (28.82%) | 41 (30.37%) | 25 (26.60%) | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Small cell lung cancer | 46 (20.09%) | 30 (22.22%) | 16 (17.02%) | 0.424 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | 183 (79.91%) | 105 (77.78%) | 78 (82.98%) | |

| Comorbidities | 127 (55.46%) | 69 (51.11%) | 58 (61.70%) | 0.113 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (18.34%) | 22 (16.30%) | 20 (21.28%) | 0.433 |

| Hypertension | 54 (23.58%) | 31 (22.96%) | 23 (24.47%) | 0.916 |

| Ischemic heart diseases | 29 (12.66%) | 14 (10.37%) | 15 (15.96%) | 0.294 |

| COPD | 39 (17.03%) | 18 (13.33%) | 21 (22.34%) | 0.108 |

| Hypothyroidism | 5 (2.18%) | 2 (1.48%) | 3 (3.19%) | 0.403 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 32 (13.97%) | 16 (11.85%) | 16 (17.02%) | 0.360 |

| Chronic renal failure | 8 (3.49%) | 5 (3.70%) | 3 (3.19%) | 1.000 |

| Congestive heart failure | 9 (3.93%) | 4 (2.96%) | 5 (5.32%) | 0.493 |

| Others | 4 (1.75%) | 2 (1.48%) | 2 (2.13%) | 1.000 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| None | 36 (16.90%) | 15 (11.81%) | 21 (24.42%) | 0.035 |

| <2 weeks | 50 (23.47%) | 29 (22.83%) | 21 (24.42%) | |

| 2–4 weeks | 33 (15.49%) | 25 (19.69%) | 8 (9.30%) | |

| >4 weeks | 94 (44.13%) | 58 (45.67%) | 36 (41.86%) | |

| Malignancy status | ||||

| Controlled/Remission | 30 (15.08%) | 12 (10.00%) | 18 (22.78%) | <0.001 |

| Newly diagnosed | 46 (23.12%) | 20 (16.67%) | 26 (32.91%) | |

| Recurrence/Progression | 123 (61.81%) | 88 (73.33%) | 35 (44.30%) | |

| Stage | ||||

| Stage I | 4 (1.97%) | 1 (0.81%) | 3 (3.75%) | 0.089 |

| Stage II | 4 (1.97%) | 1 (0.81%) | 3 (3.75%) | |

| Stage III | 8 (3.94%) | 3 (2.44%) | 5 (6.25%) | |

| Stage IV | 187 (92.12%) | 118 (95.93%) | 69 (86.25%) | |

| Reason of ICU admission | ||||

| Respiratory problems | 131 (57.21%) | 86 (63.70%) | 45 (47.87%) | <0.001 |

| Neurological problems | 21 (9.17%) | 10 (7.41%) | 11 (11.70%) | |

| Sepsis | 28 (12.23%) | 22 (16.30%) | 6 (6.38%) | |

| Postoperative | 29 (12.66%) | 3 (2.22%) | 26 (27.66%) | |

| GI bleeding | 6 (2.62%) | 5 (3.70%) | 1 (1.06%) | |

| Cardiac problems | 5 (2.18%) | 2 (1.48%) | 3 (3.19%) | |

| Others | 9 (3.93%) | 7 (5.19%) | 2 (2.13%) | |

| Length of stay in ICU | 5 (2–9) | 5 (2–11) | 4 (2–8) | 0.307 |

| MV | 196 (85.59%) | 131 (97.04%) | 65 (69.15%) | <0.001 |

| Invasive MV | 136 (59.39%) | 105 (77.78%) | 31 (32.98%) | <0.001 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.54 ± 2.05 | 10.07 ± 1.92 | 11.21 ± 2.05 | <0.001 |

| Platelet (×1000) | 191 (104–302) | 164 (69–293) | 220 (150–312) | 0.007 |

| WBC (×103/µL) | 11,100 (6920–17,230) | 11,480 (5670–18,830) | 10,970 (7220–15,550) | 0.656 |

| Neutrophil | 9410 (5350–14,900) | 9840 (5050–15,690) | 8680 (5510–13,430) | 0.332 |

| Lymphocyte | 730 (340–1230) | 620 (310–1100) | 810 (340–1550) | 0.017 |

| Eosinophil | 10 (0–30) | 0 (0–20) | 10 (0–60) | 0.002 |

| Monocyte | 560 (230–980) | 520 (190–890) | 585 (270–1000) | 0.353 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 120.6 (49.6–235.8) | 140.07 (61.74–284.58) | 109.63 (33.11–166.48) | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.91 ± 0.59 | 2.82 ± 0.57 | 3.05 ± 0.60 | 0.004 |

| LDH (U/L) | 405 (246–787) | 521 (311–1338) | 284.5 (212–443) | 0.009 |

| NLR | 12.38 (5.82–26.2) | 14.92 (6.79–28.00) | 9.85 (5.40–20.98) | 0.016 |

| PLR | 272.5 (125.6–537.9) | 267.19 (124.03–548.39) | 280.71 (142.05–504) | 0.808 |

| LMR | 1.37 (0.77–2.33) | 1.25 (0.64–2.50) | 1.46 (0.90–2.16) | 0.334 |

| SII (×1000) | 2166 (1017.5–5094.7) | 2128.3 (932.1–5703.1) | 2183.9 (1088.1–4430.2) | 0.907 |

| mGPS | ||||

| 0 | 12 (5.45%) | 1 (0.74%) | 11 (12.94%) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 36 (16.36%) | 19 (14.07%) | 17 (20.00%) | |

| 2 | 172 (78.18%) | 115 (85.19%) | 57 (67.06%) | |

| PNI | 33.55 ± 7.84 | 32.33 ± 7.18 | 35.54 ± 8.50 | 0.004 |

| APACHE score | 21.80 ± 8.84 | 25.03 ± 8.28 | 17.17 ± 7.49 | <0.001 |

| MPM II-Admission | 58 (43–80) | 71 (56–90) | 44.5 (30–55) | <0.001 |

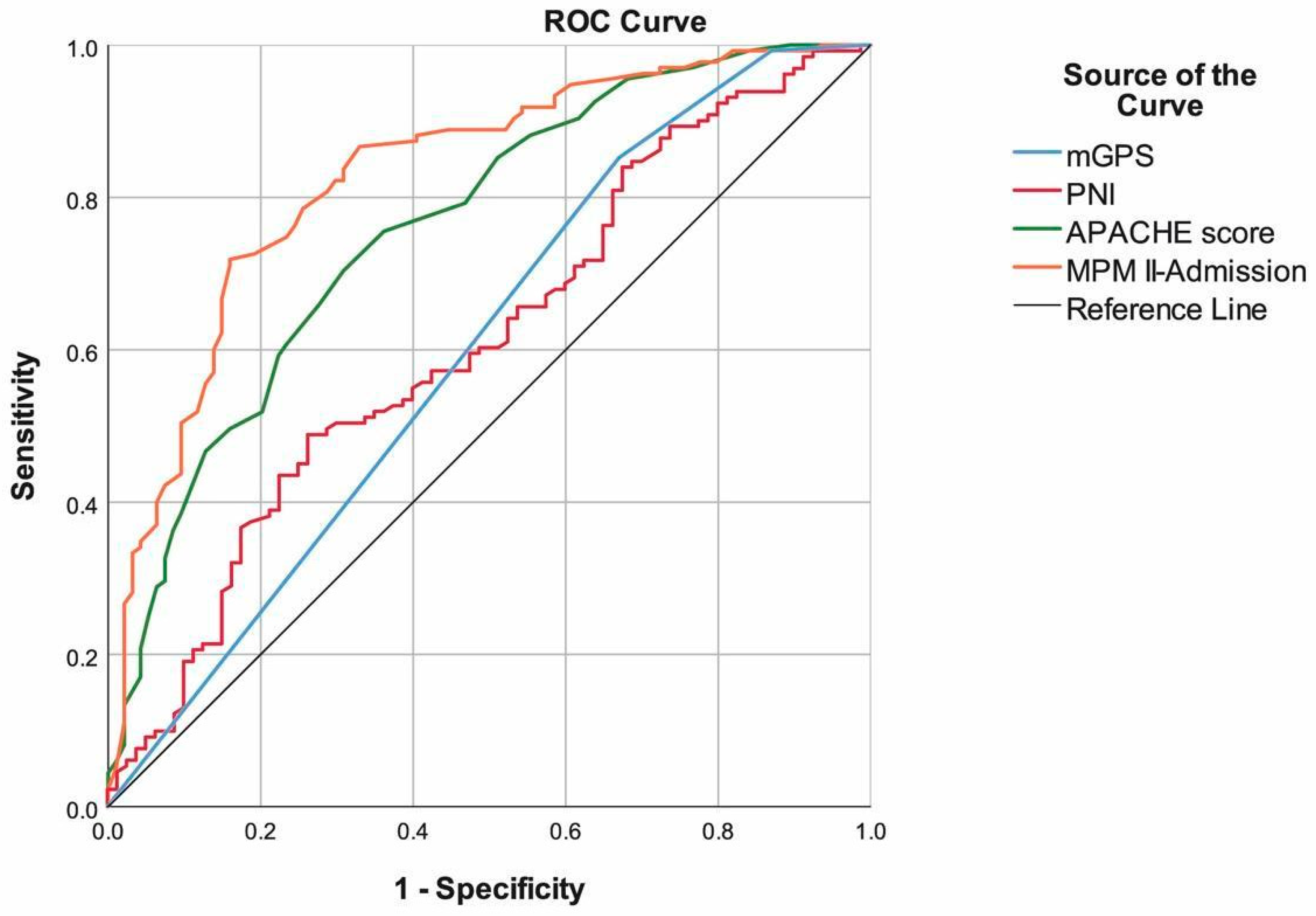

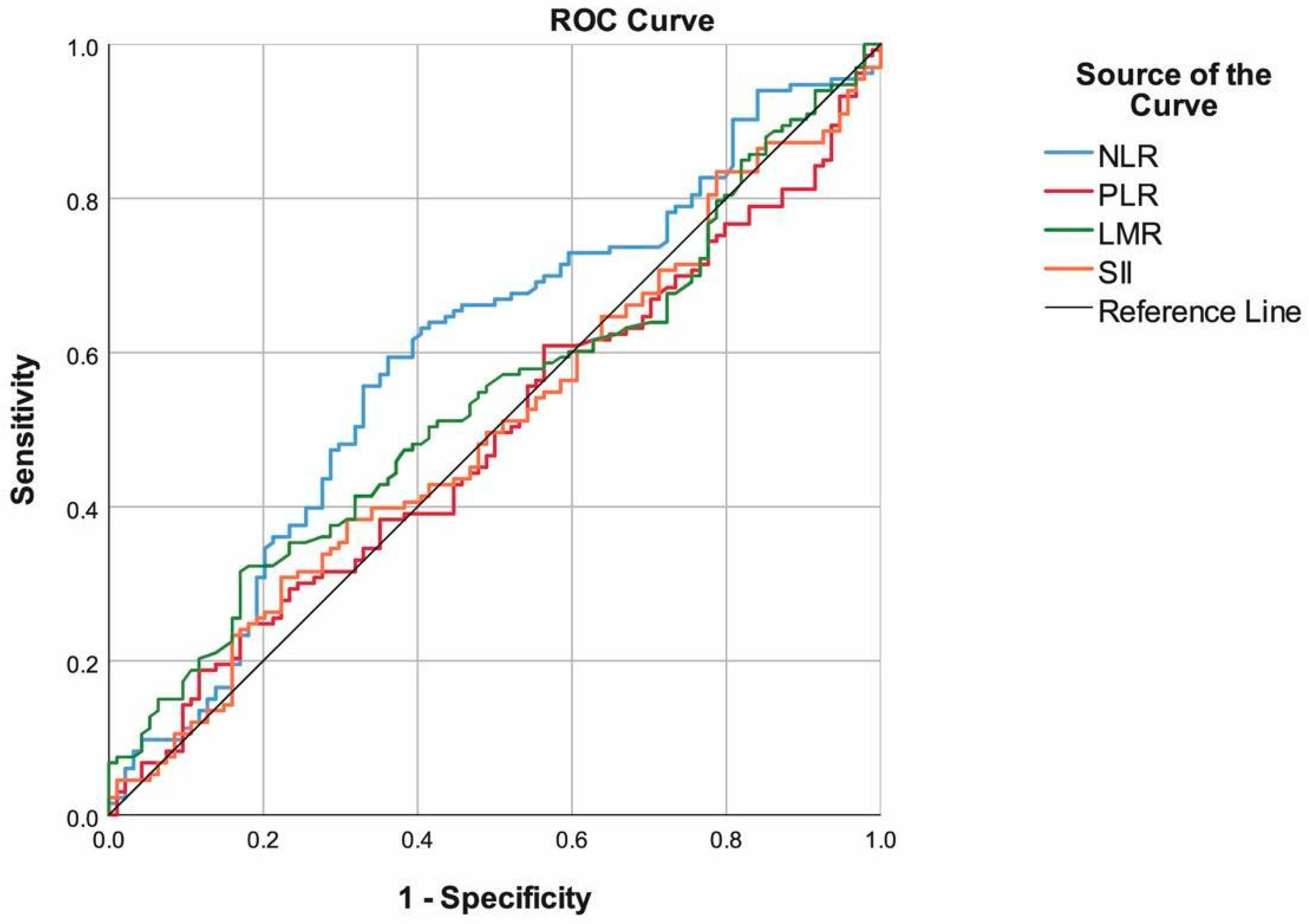

| Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | PPV | NPV | AUC (95.0% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR | ≥12.5 | 59.40% | 63.83% | 61.23% | 69.91% | 52.63% | 0.594 (0.519–0.670) | 0.016 |

| PLR | ≥200 | 60.90% | 43.62% | 53.74% | 60.45% | 44.09% | 0.491 (0.415–0.566) | 0.808 |

| LMR | <1.01 | 41.35% | 68.09% | 52.42% | 64.71% | 45.07% | 0.538 (0.463–0.613) | 0.334 |

| SII | ≥3150 | 39.85% | 65.96% | 50.66% | 62.35% | 43.66% | 0.505 (0.429–0.580) | 0.907 |

| mGPS | 2 | 85.19% | 32.94% | 65.00% | 66.86% | 58.33% | 0.599 (0.520–0.678) | 0.013 |

| PNI | <31.1 | 48.85% | 73.75% | 58.29% | 75.29% | 46.83% | 0.611 (0.533–0.689) | 0.007 |

| APACHE score | ≥20 | 70.37% | 69.15% | 69.87% | 76.61% | 61.90% | 0.762 (0.699–0.824) | <0.001 |

| MPM II-Admission | ≥59 | 71.85% | 84.04% | 76.86% | 86.61% | 67.52% | 0.829 (0.775–0.884) | <0.001 |

| β Coefficient | Standard Error | p | Exp(β) | 95.0% CI for Exp(β) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recurrence/Progression | 1.880 | 0.503 | <0.001 | 6.553 | 2.446 | 17.553 |

| Postoperative admission | −3.452 | 1.095 | 0.002 | 0.032 | 0.004 | 0.271 |

| PNI (<31.1) | 0.940 | 0.472 | 0.047 | 2.559 | 1.014 | 6.455 |

| APACHE score (≥20) | 1.051 | 0.458 | 0.022 | 2.860 | 1.165 | 7.024 |

| MPM II-Admission (≥59) | 3.376 | 0.623 | <0.001 | 29.257 | 8.635 | 99.128 |

| (Constant) | −2.360 | 0.540 | <0.001 | 0.094 | ||

| Dependent Variable: Mortality; Nagelkerke R2 = 0.632; Correct prediction = 85.87% | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tunay, B.; Olmez, O.F.; Bilici, A.; Bayramgil, A.; Cavusoglu, G.D.; Oz, H. Inflammation-Related Parameters in Lung Cancer Patients Followed in the Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare 2026, 14, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010039

Tunay B, Olmez OF, Bilici A, Bayramgil A, Cavusoglu GD, Oz H. Inflammation-Related Parameters in Lung Cancer Patients Followed in the Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010039

Chicago/Turabian StyleTunay, Burcu, Omer Fatih Olmez, Ahmet Bilici, Ayberk Bayramgil, Gunes Dorukhan Cavusoglu, and Huseyin Oz. 2026. "Inflammation-Related Parameters in Lung Cancer Patients Followed in the Intensive Care Unit" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010039

APA StyleTunay, B., Olmez, O. F., Bilici, A., Bayramgil, A., Cavusoglu, G. D., & Oz, H. (2026). Inflammation-Related Parameters in Lung Cancer Patients Followed in the Intensive Care Unit. Healthcare, 14(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010039