Co-Creating a Digital Resource to Support Smartwatch Use in COPD Self-Management: An Inclusive and Pragmatic Participatory Approach

Highlights

- A co-created digital resource (website and video) was developed with people with COPD, carers, and healthcare practitioners to support smartwatch use for COPD self-management.

- Participants identified key needs, including understanding smartwatch features, interpreting health data, and accessing relatable, practical guidance.

- The resource offers tailored support for both patients and practitioners, with potential to enhance everyday use of wearable technologies in COPD care.

- The innovative, rigorous, and inclusive co-creation process ensured the resource was relevant, acceptable, and grounded in lived experience.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Theoretical Framework

2.2. Recruitment and Participants

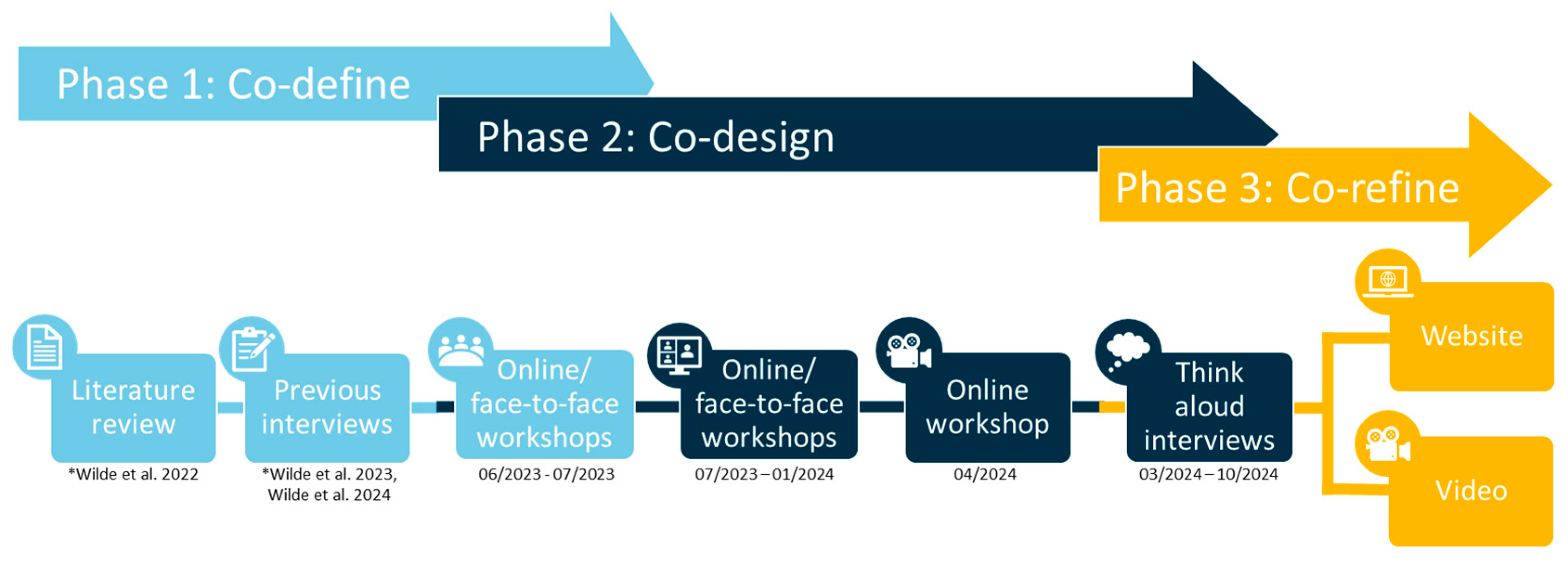

2.3. Co-Creation and Data Collection Phases

2.3.1. Phase 1: Co-Define

- Workshop 1 (06/2023) was conducted online using Zoom Whiteboard, allowing participants to express ideas visually and verbally (see Supplementary Materials S1).

- Workshop 2 (07/2023) was held face-to-face at a local pulmonary rehabilitation programme using paper-based tools (see Supplementary Materials S2).

2.3.2. Phase 2: Co-Design

- Workshop 3 (07/2023) was conducted online using Zoom Whiteboard to prioritise content and format (see Supplementary Materials S3).

- Workshop 4 (01/2024) was held face-to-face and focused on developing content specifically for healthcare practitioners. Participants reviewed a printed version of the draft website and provided feedback on what information would be most useful in clinical settings.

- Workshop 5 (04/2024) gathered feedback on a draft version of the video component.

2.3.3. Phase 3: Co-Refine

- Participants were given the option to either view a screen-shared version of the draft or edit a live Word document themselves. Three chose the screen-share option, which was used consistently thereafter. The researcher used tracked changes to make edits and document iterative updates ready for the next participant. A table of changes was maintained to ensure transparency.

- During interviews, participants navigated the website prototype, developed (by LW) using WordPress (Automattic Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), while sharing their screen. This allowed the researcher to observe user journeys and gather feedback on layout, language, and usability.

- In some cases, the researcher made live edits in WordPress to demonstrate changes and gather immediate reactions.

- Participants were also offered the option to test the website independently and provide feedback via email.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Reflexivity

2.6. Ethical Approval and Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Development Phases and Analysis

3.2.1. Phase 1: Co-Define—Identifying Needs and Priorities

We need to be informed on what these devices can actually do so that we can appropriately advise.(P1, Workshop 1)

I think you need to do something that would be creating some education materials for healthcare professionals, so that they can become aware of what wearables can do and how they might help.(P5, Workshop 1)

So, I suppose it’s giving them the knowledge isn’t it… Then you don’t want them to worry if [oxygen saturation] is just from your finger, some of them all look at their watch and they’ll panic like “Oh my God, it’s below 90. Ohh I’m not OK” and like instantly panic. And actually with their condition it’s not uncommon that it’s below.(P14, Workshop 2)

When you’ve got people’s experiences, it makes you feel a little bit more comfortable that you’re not out there on your own.(P9, Workshop 3)

It’s just a bit more time, isn’t it? Because you would spend more time with people going through it really…(P15, Workshop 2)

I think conversation is the most important thing, isn’t it?(P14, Workshop 2)

3.2.2. Phase 2: Co-Design—Shaping the Format and Content

I think the leaflet is probably … the last thing you need.(P14, Workshop 2)

I feel like this type of information could still be on the Asthma and Lung UK website … then it’s in that category of general information for everyone.(P3, Workshop 3)

Video’s the way forward with this…(P4, Workshop 3)

I would prefer an app … it’s more accessible if it’s on my phone… If I needed to know how to use something to do with my wearable and I’m out, then it’s much more accessible.(P5, Workshop 3)

Start with the patient side … then build the practitioner bit around it.(P14, Workshop 3)

3.2.3. Phase 3: Co-Refine—Iterative Testing and Feedback

Maybe even having bold on the specific sentence within the paragraph that is the actual point.(P3)

I wonder if we could change the photo here for an inhaler…(P33)

That’s [navigation] really easy. Even just like the drop-down boxes, they come down so easy and so quick … Everything so well laid out and so easy.(P18)

Yeah, but then I suppose at the same time, you could also link them that to that, that page, the patient page.(P14)

I think it’s worth adding as well their heart rate … Well, it’s just heart rate monitoring.(P2)

Yeah, yeah. Knowledge that you may plateau at the same level so, you know, sometimes maintaining is a win. Yeah, that’s probably what I would put there …(P20)

It’s useful to put it in there. Maybe if you can’t handle your step goal in one go to do two sessions, one in the morning and one in the evening, or break it down into bite sized chunks.(P4)

How? What can smartwatches do to help with COPD management? I wonder whether about using the word ‘you’ in there. Actually, ‘how’ can smartwatches help ‘you’ manage your COPD, so it becomes a bit more direct?(P20)

OK, I wouldn’t call it ‘breathing exercises’. I will tell you why. But but that’s me that I’m very particular about this because we are not exercising anything. If they are like breathing techniques, I will call it, and perhaps not all are effective, not all are actually good, but it’s like you could mention one technique which got some evidence is called pursed breathing.(P33)

No, it’s it’s good. It’s good, I think it’s. I think it’s a good start. You know, it’s to start the conversation as well between the healthcare professionals and patients. And you know and give the information because it’s like it may be easier for healthcare professionals to to, you know, to give to have a place to go to, to start these conversations.(P33)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| HCP | Healthcare Practitioner |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- World Health Organization. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-%28copd%29 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Snell, N.; Strachan, D.; Hubbard, R.; Gibson, J.; Gruffydd-Jones, K.; Jarrold, I. S32 Epidemiology of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in the Uk: Findings from the British Lung Foundation’s ‘Respiratory Health of the Nation’ Project. Thorax 2016, 71, A20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canali, S.; Ferretti, A.; Schiaffonati, V.; Blasimme, A. Wearable Technologies for Healthy Ageing: Prospects, Challenges, and Ethical Considerations. J. Frailty Aging 2024, 13, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Mahmoud, A.; Massoomi, M.R. A Clinician’s Guide to Smartwatch “Interrogation”. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2022, 24, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutu, F.-A.; Iorio, O.C.; Ross, B.A. Remote Patient Monitoring Strategies and Wearable Technology in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1236598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, C.; McCann, M.; Brady, A.M. Computer and Mobile Technology Interventions for Self-management in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2020, CD011425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.J.; Althobiani, M.A.; Saigal, A.; Ogbonnaya, C.E.; Hurst, J.R.; Mandal, S. Wearable Technology Interventions in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpershoek, Y.J.G.; Vervoort, S.; Trappenburg, J.C.A.; Schuurmans, M.J. Perceptions of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Their Health Care Providers towards Using mHealth for Self-Management of Exacerbations: A Qualitative Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, B.; Nilsson, C.; Zotterman, D.; Söderberg, S.; Skär, L. Using Information and Communication Technology in Home Care for Communication between Patients, Family Members, and Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Telemed. Appl. 2013, 2013, 461829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasella, F.; Morgan, H.M. “Sometimes I Don’t Have a Pulse … and I’m Still Alive!” Interviews with Healthcare Professionals to Explore Their Experiences of and Views on Population-Based Digital Health Technologies. Digit. Health 2021, 7, 20552076211018366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, L.J.; Sewell, L.; Percy, C.; Ward, G.; Clark, C. What Are the Experiences of People with COPD Using Activity Monitors?: A Qualitative Scoping Review. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2022, 19, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.M.; Apps, L.D.; Harrison, S.L.; Johnson-Warrington, V.L.; Hudson, N.; Singh, S.J. Important, Misunderstood, and Challenging: A Qualitative Study of Nurses’ and Allied Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Implementing Self-Management for Patients with COPD. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2015, 10, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, K.; Arnold, J.; Maher, C. The Wearable Activity Tracker Checklist for Healthcare (WATCH): A 12-Point Guide for the Implementation of Wearable Activity Trackers in Healthcare. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaptain, R.J.; Helle, T.; Larsen, S.M. Everyday Technology and Assistive Technology Supporting Everyday Life Activities in Adults Living with COPD—A Narrative Literature Review. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2025, 20, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, L.J.; Percy, C.; Ward, G.; Clark, C.; Wark, P.A.; Sewell, L. The Experiences of People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Using Activity Monitors in Everyday Life: An Interpretative Phenomenological Study. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 5479–5489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.C.; Ginsburg, S.; Son, T.; Gershon, A.S. Using Wearables and Self-Management Apps in Patients with COPD: A Qualitative Study. ERJ Open Res. 2019, 5, 00036–02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.C.; de Lara, E.; Liaqat, D.; Liaqat, S.; Chen, J.L.; Son, T.; Gershon, A.S. Feasibility of a Wearable Self-Management Application for Patients with COPD at Home: A Pilot Study. BMC Med. Inf. Decis. Mak. 2024, 24, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillol, T.; Strik, M.; Ramirez, F.D.; Abu-Alrub, S.; Marchand, H.; Buliard, S.; Welte, N.; Ploux, S.; Haïssaguerre, M.; Bordachar, P. Accuracy of a Smartwatch-Derived ECG for Diagnosing Bradyarrhythmias, Tachyarrhythmias, and Cardiac Ischemia. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2021, 14, e009260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Exworthy, M. Wearing the Future-Wearables to Empower Users to Take Greater Responsibility for Their Health and Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022, 10, e35684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, L.J.; Percy, C.; Clark, C.; Ward, G.; Wark, P.A.; Sewell, L. Views and Experiences of Healthcare Practitioners Supporting People with COPD Who Have Used Activity Monitors: “More than Just Steps”. Respir. Med. 2023, 218, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabeidi, F.; Aljawad, H.M.; Alswaied, K.A.; Alanazi, R.N.; Aljabri, M.S.; Jaafari, A.A.; Alanazi, A.J.; Alhomod, K.A.; Alhamed, A.A.; Alhizan, K.A.; et al. Interventions Utilizing Smartwatches in Healthcare: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 8, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, G.; Magee, P. Co-Creation Solutions and the Three Co’s Framework for Applying Co-Creation. Health Educ. 2024, 124, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, G.; Holliday, N.; Sandhu, H.; Eftekhari, H.; Bruce, J.; Timms, E.; Ablett, L.; Kavi, L.; Simmonds, J.; Evans, R.; et al. Co-Creation of a Complex, Multicomponent Rehabilitation Intervention and Feasibility Trial Protocol for the PostUraL Tachycardia Syndrome Exercise (PULSE) Study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2023, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Cardon, G.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Verloigne, M.; Chastin, S.F.M.; on behalf of the GrandStand, S.S. and T.G. on the M.R.G. Framework, Principles and Recommendations for Utilising Participatory Methodologies in the Co-Creation and Evaluation of Public Health Interventions. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2019, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Haak, M.J.; de Jong, M.D.T.; Schellens, P.J. Evaluation of an Informational Web Site: Three Variants of the Think-Aloud Method Compared. Tech. Commun. 2007, 54, 58–71. [Google Scholar]

- Coventry University. COPD and Smartwatches Website Launch Event; Coventry University: Coventry, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- COPD and Smartwatches. Available online: https://copdandsmartwatches.coventry.domains/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Lundell, S.; Toots, A.; Sönnerfors, P.; Halvarsson, A.; Wadell, K. Participatory Methods in a Digital Setting: Experiences from the Co-Creation of an eHealth Tool for People with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2022, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellsdotter, A.; Andersson, S.; Berglund, M. Together for the Future—Development of a Digital Website to Support Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Self-Management: A Qualitative Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, ume 14, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-002092-4. [Google Scholar]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

|

|

| Participant Number *, Role (n = 21) | Co-Define | Co-Design | Co-Refine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workshop 1 (06/2023) | Workshop 2 (07/2023) | Workshop 3 (07/2023) | 1-1 Interviews | Workshop 4 (01/2024) | Workshop 5 (04/2024) | 1-1 Interviews | Feedback via Email | |

| 1, HCP | X | |||||||

| 2, HCP | 09/2023 | |||||||

| 3, Friend | X | X | 09/2023 | 08/2024 | X | |||

| 4, COPD | X | X | 10/2023 | X | 03/2024 | |||

| 5, COPD | X | X | ||||||

| 9, COPD | X | 11/2023 | X | 10/2024 | ||||

| 12, HCP | X | X | X | |||||

| 14, HCP | X | X | X | |||||

| 15, HCP | X | X | ||||||

| 16, HCP | X | X | X | |||||

| 18, HCP | 09/2024 | |||||||

| 21, COPD | 12/2023 | X | ||||||

| 22, HCP | 09/2024 | |||||||

| 24, HCP | X | 05/2024 | ||||||

| 26, Charity | 04/2024 | |||||||

| 27, Friend | 05/2024 | |||||||

| 28, HCP | 08/2024 | X | ||||||

| 32, Friend | X | |||||||

| 33, HCP | 10/2024 | |||||||

| 34, Researcher | X | |||||||

| 35, Researcher | X | |||||||

| Demographic | Age in years, Mean (Range) | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Friend, family or carer (n = 3) | 33.7 (31–38) | 1 female, 2 male |

| People with COPD (n = 4) | 60.5 (38–69) | 1 female, 2 male, 1 transgender |

| Healthcare practitioners (n = 11) | 41.9 (24–63) | 8 female, 3 male |

| Researchers (n = 2) | 38.5 (27–50) | 2 female |

| Charity representative (n = 1) | 67 | 1 male |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wilde, L.J.; Sewell, L.; Holliday, N. Co-Creating a Digital Resource to Support Smartwatch Use in COPD Self-Management: An Inclusive and Pragmatic Participatory Approach. Healthcare 2026, 14, 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010037

Wilde LJ, Sewell L, Holliday N. Co-Creating a Digital Resource to Support Smartwatch Use in COPD Self-Management: An Inclusive and Pragmatic Participatory Approach. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):37. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010037

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilde, Laura J., Louise Sewell, and Nikki Holliday. 2026. "Co-Creating a Digital Resource to Support Smartwatch Use in COPD Self-Management: An Inclusive and Pragmatic Participatory Approach" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010037

APA StyleWilde, L. J., Sewell, L., & Holliday, N. (2026). Co-Creating a Digital Resource to Support Smartwatch Use in COPD Self-Management: An Inclusive and Pragmatic Participatory Approach. Healthcare, 14(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010037