Bias at the Bedside: A Comprehensive Review of Racial, Sexual, and Gender Minority Experiences and Provider Attitudes in Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

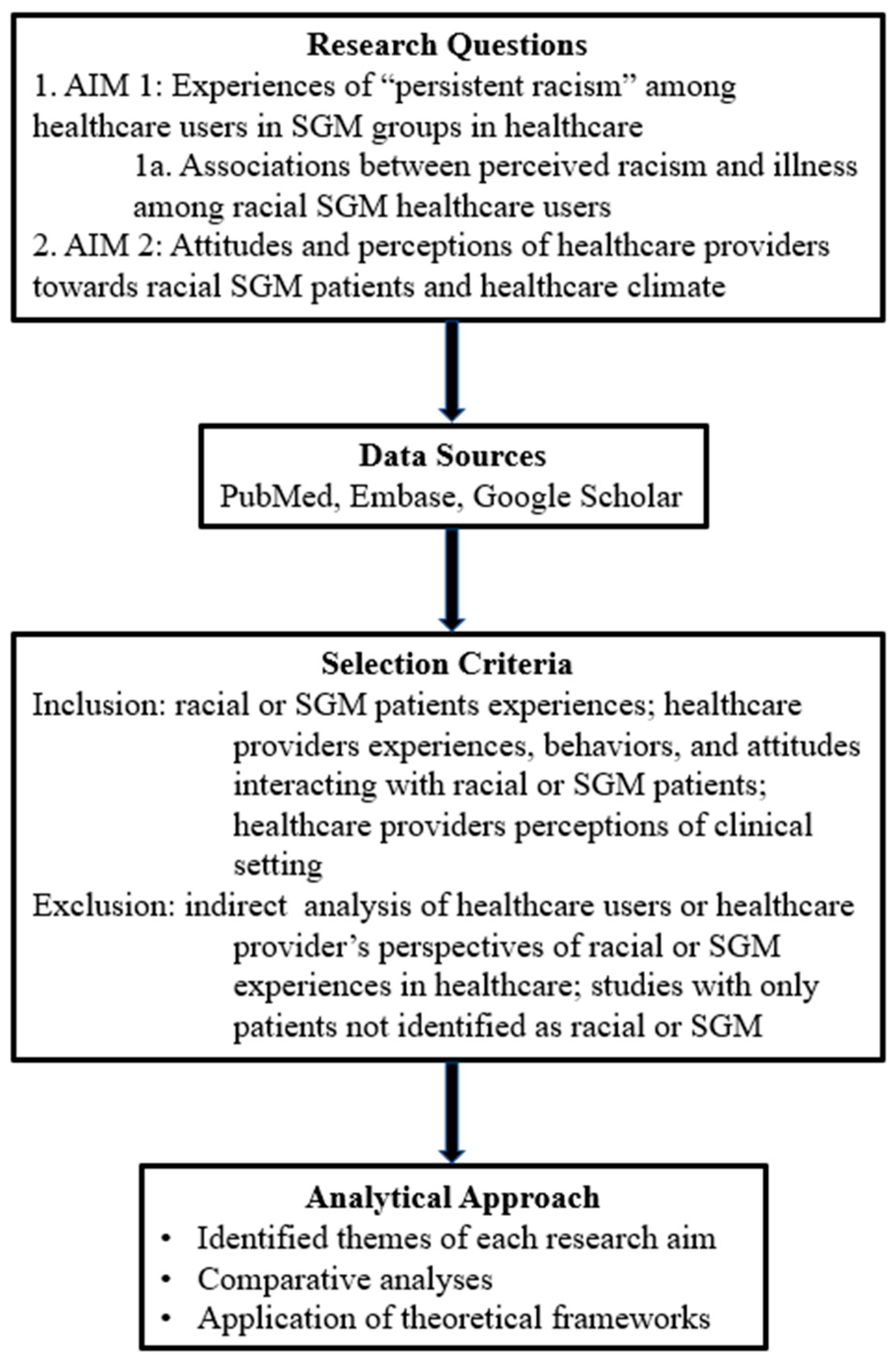

2. Methods

- What are the experiences of “persistent racism”, defined here as repeated and enduring experiences of discrimination embedded within healthcare interactions and institutional practices over time, among healthcare users in sexual minority groups in medical settings?

- What are the associations between perceived racism in healthcare settings and perception of illness among healthcare users at the intersections of race, gender identity, and sexual orientation?

- What are the attitudes and perceptions of healthcare providers towards racial interaction or climate in healthcare?

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Scope

2.4. Analytical Approach

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Perceptions of Healthcare Users

3.1.1. Experiences of Discrimination and Stigma

3.1.2. Coping Mechanisms

3.1.3. Health Impacts

3.1.4. Communication Gaps

3.1.5. Intersectionality

3.2. Perceptions of Healthcare Providers

3.2.1. Implicit and Explicit Bias

3.2.2. Knowledge & Training Gaps

3.2.3. Attitudinal Variability

3.2.4. Communication & Behavior

3.2.5. Workplace Dynamics

3.3. Comparative Analysis

3.3.1. Convergence: Shared Recognition of Discrimination and Gaps in Care

3.3.2. Divergence: Perception Gaps in Frequency and Impact of Bias

3.3.3. Structural vs. Interpersonal Bias: Systemic Mistrust vs. Individual Framing

3.4. Policy and Practice Implications

3.5. Summary

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayhan, C.H.B.; Bilgin, H.; Uluman, O.T.; Sukut, O.; Yilmaz, S.; Buzlu, S. A Systematic Review of the Discrimination Against Sexual and Gender Minority in Health Care Settings. Int. J. Health Serv. Plan. Adm. Eval. 2020, 50, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feagin, J.; Bennefield, Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, E.; Dhingra, N. Health Care Inequities of Sexual and Gender Minority Patients. Dermatol. Clin. 2020, 38, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, M.A.; Futterman, L.A.; Lotz-Nigh, A.T.; Eteminan, S. The Dissectionality of Care in the U.S.: A Scoping Review in Healthcare of Implicit Bias, Perceived Discrimination, and Minority Stress Among Sexual and Gender Minorities. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2025, 54, 2005–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.H. Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Z.D.; Krieger, N.; Agénor, M.; Graves, J.; Linos, N.; Bassett, M.T. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017, 389, 1453–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, T.; Simmons, A. Intersectional structural stigma, community priorities, and opportunities for transgender health equity: Findings from TRANSforming the Carolinas. J. Law Med. Ethics 2022, 50, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, D.J.; Bokhour, B.G.; Cunningham, B.A.; Do, T.; Gordon, H.S.; Jones, D.M.; Pope, C.; Saha, S.; Gollust, S.E. Healthcare Providers’ Responses to Narrative Communication About Racial Healthcare Disparities. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradies, Y.; Truong, M.; Priest, N. A Systematic Review of the Extent and Measurement of Healthcare Provider Racism. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2014, 29, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, G.C.; Ford, C.L. Structural racism and health inequities: Old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011, 8, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, L.R.M.; Kressin, N.R.; Hanusa, B.H.; Ibrahim, S.A. Perceived racial discrimination in health care and its association with patients’ health care experiences. Med. Care 2011, 49, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabish, K.; Theeke, L.A. Health Impact of Stigma, Discrimination, Prejudice, and Bias Experienced by Transgender People: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.M.; Mottet, L.A.; Tanis, J.; Harrison, J.; Herman, J.L.; Keisling, M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- James, S.E.; Herman, J.L.; Rankin, S.; Keisling, M.; Mottet, L.; Anafi, M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey; National Center for Transgender Equality: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Seelman, K.L.; Colón-Diaz, M.J.P.; LeCroix, R.H.; Xavier-Brier, M.; Kattari, L. Transgender non-inclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: Connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgender Health 2017, 2, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 1267–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, G.R. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 110, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, W.J.; Chapman, M.V.; Lee, K.M.; Merino, Y.M.; Thomas, T.W.; Payne, B.K.; Eng, E.; Day, S.H.; Coyne-Beasley, T. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e60–e76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- FitzGerald, C.; Hurst, S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMC Med. Ethics 2017, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.N.; Kaatz, A.; Carnes, M. Physicians and implicit bias: How doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2013, 28, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ryn, M.; Hardeman, R.; Phelan, S.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Dovidio, J.F.; Herrin, J.; Burke, S.E.; Nelson, D.B.; Perry, S.; Yeazel, M.; et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: A Medical Student CHANGES Study Report. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1748–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, I.V.; Steiner, J.F.; Fairclough, D.L.; Hanratty, R.; Price, D.W.; Hirsh, H.K.; Wright, L.A.; Bronsert, M.; Karimkhani, E.; Magid, D.J.; et al. Clinicians’ Implicit Ethnic/Racial Bias and Perceptions of Care Among Black and Latino Patients. Ann. Fam. Med. 2013, 11, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maina, I.W.; Belton, T.D.; Ginzberg, S.; Singh, A.; Johnson, T.J. A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 199, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelin, J.R.; Siraj, D.S.; Victor, R.; Kotadia, S.; Maldonado, Y.A. The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, S62–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smedley, B.D.; Stith, A.Y.; Nelson, A.R. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, C.; Boehmer, U.; Jesdale, B.M. Perceptions of patient-provider communications with healthcare providers among sexual and gender minority individuals in the United States. Patient Educ. Couns. 2024, 127, 108347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apodaca, C.; Casanova-Perez, R.; Bascom, E.; Mohanraj, D.; Lane, C.; Vidyarthi, D.; Beneteau, E.; Sabin, J.; Pratt, W.; Weibel, N.; et al. Maybe they had a bad day: How LGBTQ and BIPOC patients react to bias in healthcare and struggle to speak out. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. JAMIA 2022, 29, 2075–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Hughto, J.M.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiwara, N.; Slatcher, R.B.; Eggly, S.; Penner, L.A. Physician Racial Bias and Word Use during Racially Discordant Medical Interactions. Health Commun. 2017, 32, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cruciani, G.; Quintigliano, M.; Mezzalira, S.; Scandurra, C.; Carone, N. Attitudes and knowledge of mental health practitioners towards LGBTQ+ patients: A mixed-method systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2024, 113, 102488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.D. Examining the Unconscious Racial Biases and Attitudes of Physicians, Nurses, and the Public: Implications for Future Health Care Education and Practice. Health Equity 2022, 6, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagkozidis, I.; Haidich, A.B.; Athanasiadis, L.; Dardavesis, T.; Tsimtsiou, Z. Qualitative Insights Into Healthcare Professionals’ Perceived Barriers in Providing Equitable and Patient-Centered Care to Members of the LGBTQI+ Community in Greece. Health Promot. Pract. 2025, 26, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 35, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.; Mohammed, S.A. Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. Am. Behav. Sci. 2013, 57, 1152–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiner, B. An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychol. Rev. 1985, 92, 548–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heider, F. The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Penner, L.A.; Albrecht, T.L.; Norton, W.E.; Gaertner, S.L.; Shelton, J.N. Implicit racial bias in health care: How it affects patient–provider communication and health outcomes. Am. Psychol. 2017, 72, 741–752. [Google Scholar]

- Braveman, P.; Arkin, E.; Orleans, T.; Proctor, D.; Plough, A. What is health equity? And what difference does a definition make? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campodarve, A.; Täuber, S.; Gutierrez, B. Experiences of Discrimination and LGBTQ+ Healthcare Avoidance: A Social Psychology Study from the Perspective of Patients and Healthcare Professionals. Tijdschr. Voor Genderstudies 2025, 28, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamen, C.S.; Alpert, A.; Margolies, L.; Griggs, J.J.; Darbes, L.; Smith-Stoner, M.; Lytle, M.; Poteat, T.; NFN Scout; Norton, S.A. “Treat us with dignity”: A qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 2525–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.S.W.; Leung, L.M.; Wong, F.K.C.; Ho, J.M.C.; Tam, H.L.; Tang, P.M.K.; Yan, E. Needs and experiences of cancer care in patients’ perspectives among the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer community: A systematic review. Soc. Work Health Care 2023, 62, 263–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, C.; Stein, G.L.; Rosa, W.E.; Acquaviva, K.D.; Godfrey, D.; Woody, I.; Maingi, S.; gonzález-rivera, c.; Candrian, C.; O’Mahony, S.; et al. Discriminatory health care reported by seriously ill LGBTQ+ persons and partners: Project Respect. Palliat. Support. Care 2025, 23, e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanova-Perez, R.; Apodaca, C.; Bascom, E.; Mohanraj, D.; Lane, C.; Vidyarthi, D.; Beneteau, E.; Sabin, J.; Pratt, W.; Weibel, N.; et al. Broken down by bias: Healthcare biases experienced by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ patients. In Proceedings of the AMIA 2021 Annual Symposium Proceedings, AMIA Symposium, San Diego, CA, USA, 30 October–3 November 2021; pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, V.M.; Rice, J.B.; Schmitz, K.H. Mixed-methods health services research: Integrating surveys and qualitative inquiry. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 55, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C.M.; Ark, T.K.; Fisher, M.R.; Marantz, P.R.; Burgess, D.J.; Milan, F.; Samuel, M.T.; Lypson, M.L.; Rodriguez, C.J.; Kalet, A.L. Racial Implicit Bias and Communication Among Physicians in a Simulated Environment. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e242181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.M.; Moulder, R.; Harper, F.W.K.; Manojlovich, M.; Ramseyer, F.T.; Penner, L.A.; Albrecht, T.L.; Boker, S.; Bagautdinova, D.; Eggly, S. The Influence of Patient and Physician Race-Related Attitudes and Perceptions on Nonverbal Synchrony in Oncology Treatment Interactions Between Black Patients and Non-Black Physicians. Cancer Control. 2025, 32, 10732748251375517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.A.; Roter, D.L.; Carson, K.A.; Beach, M.C.; Sabin, J.A.; Greenwald, A.G.; Inui, T.S. The associations between clinicians’ implicit attitudes toward race and medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.D.; Jewell, J.; Sherman, A.D.F.; Balthazar, M.S.; Murray, S.B.; Bosse, J.D. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer People’s Experiences of Stigma Across the Spectrum of Inpatient Psychiatric Care: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2025, 34, e13455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalı, Ö.C.; Baba, İ.; Bayrakcı, F.; Değerli, D.; Erden, A.; Peker, M.S.; Perk, F.G.; Sipahi, İ.S.; Şenoğlu, E.; Yılmaz, S.; et al. Experience of sexual and gender minority youth when accessing health care in Turkey. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2021, 33, 445–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, R.J.; Derlega, V.J.; Clarke, E.G.; Kuang, J.C.; Jacobs, A.M. Stress, coping, and health in sexual minorities. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2017, 87, 386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal, K.; Bhatia, R.; Greene, G.J. Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences Within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults. LGBT Health 2016, 3, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I.; Kim, H.-J.; Shiu, C.; Goldsen, J.; Emlet, C.A. Successful aging among LGBTQ older adults. Gerontologist 2017, 57, S95–S107. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G. Stigma is a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, J.L.; King, D.; Carswell, J.M.; Keuroghlian, A.S. Pubertal suppression for transgender youth and risk of suicidal ideation. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.M.; Deno, M.L.; Kintzer, E.; Marantz, P.R.; Lypson, M.L.; McKee, M.D. Patient perspectives on racial and ethnic implicit bias in clinical encounters: Implications for curriculum development. Patient Educ. Couns. 2018, 101, 1669–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.R.; Carney, D.R.; Pallin, D.J.; Ngo, L.H.; Raymond, K.L.; Iezzoni, L.I.; Banaji, M.R. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, J.A.; Rivara, F.P.; Greenwald, A.G. Physicians’ implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med. Care 2008, 46, 678–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, P.; Ruzycki, S.M.; Hernandez, S.; Carbert, A.; Holroyd-Leduc, J.; Ahmed, S.; Barnabe, C. Prevalence and characteristics of anti-Indigenous bias among Albertan physicians: A cross-sectional survey and framework analysis. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e063178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, B.; Smylie, J. First Peoples, Second-Class Treatment: The Role of Racism in the Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples in Canada; Wellesley Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, E.A.; Tolle, S.; Suedbeck, J.R. Color-blind racial attitudes in practicing dental hygienists. J. Dent. Hyg. Online 2022, 96, 25–34. Available online: https://www.ezproxy.library.unlv.edu/login?qurl=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.proquest.com%2Fscholarly-journals%2Fcolor-blind-racial-attitudes-practicing-dental%2Fdocview%2F2754553965%2Fse-2%3Faccountid%3D3611 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Metzl, J.M.; Hansen, H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 103, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhab, A.; Radjack, R.; Moro, M.R.; Lambert, M. Racial biases in clinical practice and medical education: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obedin-Maliver, J.; Goldsmith, E.S.; Stewart, L.; White, W.; Tran, E.; Brenman, S.; Wells, M.; Fetterman, D.M.; Garcia, G.; Lunn, M.R. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-related content in undergraduate medical education. JAMA 2011, 306, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, A.H.; Schneider, E.B.; Sriram, N.; Dossick, D.S.; Scott, V.K.; Swoboda, S.M.; Losonczy, L.; Haut, E.R.; Efron, D.T.; Pronovost, P.J.; et al. Unconscious Race and Social Class Bias Among Acute Care Surgical Clinicians and Clinical Treatment Decisions. JAMA Surg. 2015, 150, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabin, J.A.; Riskind, R.G.; Nosek, B.A. Health Care Providers’ Implicit and Explicit Attitudes Toward Lesbian Women and Gay Men. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.R.; Lawrence, J.A.; Davis, B.A. Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trawalter, S.; Driskell, S.; Davidson, M.N. From anxious to empathetic: Intergroup anxiety, empathy, and perspective-taking in medical interactions. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2020, 14, e12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, E.; Konrad, C.M.; Khan-Gökkaya, S.; Molwitz, I.; Nawabi, J.; Yamamura, J.; Hamm, B.; Keller, S. Foreign Healthcare Professionals in Germany: A Questionnaire Survey Evaluating Discrimination Experiences and Equal Treatment at Two Large University Hospitals. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.A.; Elliott, L.; Catton, H. Racism and discrimination in the nursing workforce: A global call to action. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2023, 70, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Costa, I.; Truong, M.; Russell, L.; Adams, K. Employee perceptions of race and racism in an Australian hospital. Soc. Sci. Med. 2023, 339, 116364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.M.H.; Ramirez, X.R.; Watkins, D.N.; Sbrilli, M.D.; Lee, B.A.; Hsieh, W.J.; Wong, A.; Worthington, V.K.; Tabb, K.M. Impact of Racial Bias on Providers’ Empathic Communication Behaviors with Women of Color in Postpartum Checkup. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meidert, U.; Dönnges, G.; Bucher, T.; Wieber, F.; Gerber-Grote, A. Unconscious bias among health professionals: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalmant, K.E.; Ettinger, A.K. The Racial Disparities in Maternal Mortality and Impact of Structural Racism and Implicit Racial Bias on Pregnant Black Women: A Review of the Literature. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024, 11, 3658–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, P.G.; Forscher, P.S.; Austin, A.J.; Cox, W.T.L. Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnes, M.; Devine, P.G.; Isaac, C.; Manwell, L.B.; Ford, C.E.; Byars-Winston, A.; Fine, E.; Sheridan, J. Promoting institutional change through bias literacy. J. Divers. High. Educ. 2015, 8, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, J.; Moskowitz, G.B. Non-conscious bias in medical decision making: What can be done to reduce it? Med. Educ. 2011, 45, 768–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardeman, R.R.; Medina, E.M.; Kozhimannil, K.B. Structural racism and supporting Black lives—The role of health professionals. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 375, 2113–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theory | Level of Analysis | Core Constructs | Application in Review |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minority Stress Theory [5] | Individual/ interpersonal | Chronic stigma leading to stress and health outcomes | Explain patient avoidance, coping, and mistrust |

| Structural Racism Theory [2] | Institutional/ systemic | Policy and organizational inequity | Frames overall provider bias as systemic, not personal |

| Intersectionality [16] | Cross-level | Intersecting identities and compounding marginalization | Provides clarity to the cumulative disadvantage among SGM and racial minorities |

| Attribution Theory [36] | Cognitive/ psychological | Internal vs. external causal reasoning | Explains the perception gaps between providers and patients |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Carter, E.J.R.; Sagaribay, R.; Singh, A.; Evangelista, L.S.; Kuhls, D.A.; Pharr, J.R.; Batra, K. Bias at the Bedside: A Comprehensive Review of Racial, Sexual, and Gender Minority Experiences and Provider Attitudes in Healthcare. Healthcare 2026, 14, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010114

Carter EJR, Sagaribay R, Singh A, Evangelista LS, Kuhls DA, Pharr JR, Batra K. Bias at the Bedside: A Comprehensive Review of Racial, Sexual, and Gender Minority Experiences and Provider Attitudes in Healthcare. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010114

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarter, Emily J. R., Roberto Sagaribay, Aditi Singh, Lorraine S. Evangelista, Deborah A. Kuhls, Jennifer R. Pharr, and Kavita Batra. 2026. "Bias at the Bedside: A Comprehensive Review of Racial, Sexual, and Gender Minority Experiences and Provider Attitudes in Healthcare" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010114

APA StyleCarter, E. J. R., Sagaribay, R., Singh, A., Evangelista, L. S., Kuhls, D. A., Pharr, J. R., & Batra, K. (2026). Bias at the Bedside: A Comprehensive Review of Racial, Sexual, and Gender Minority Experiences and Provider Attitudes in Healthcare. Healthcare, 14(1), 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010114