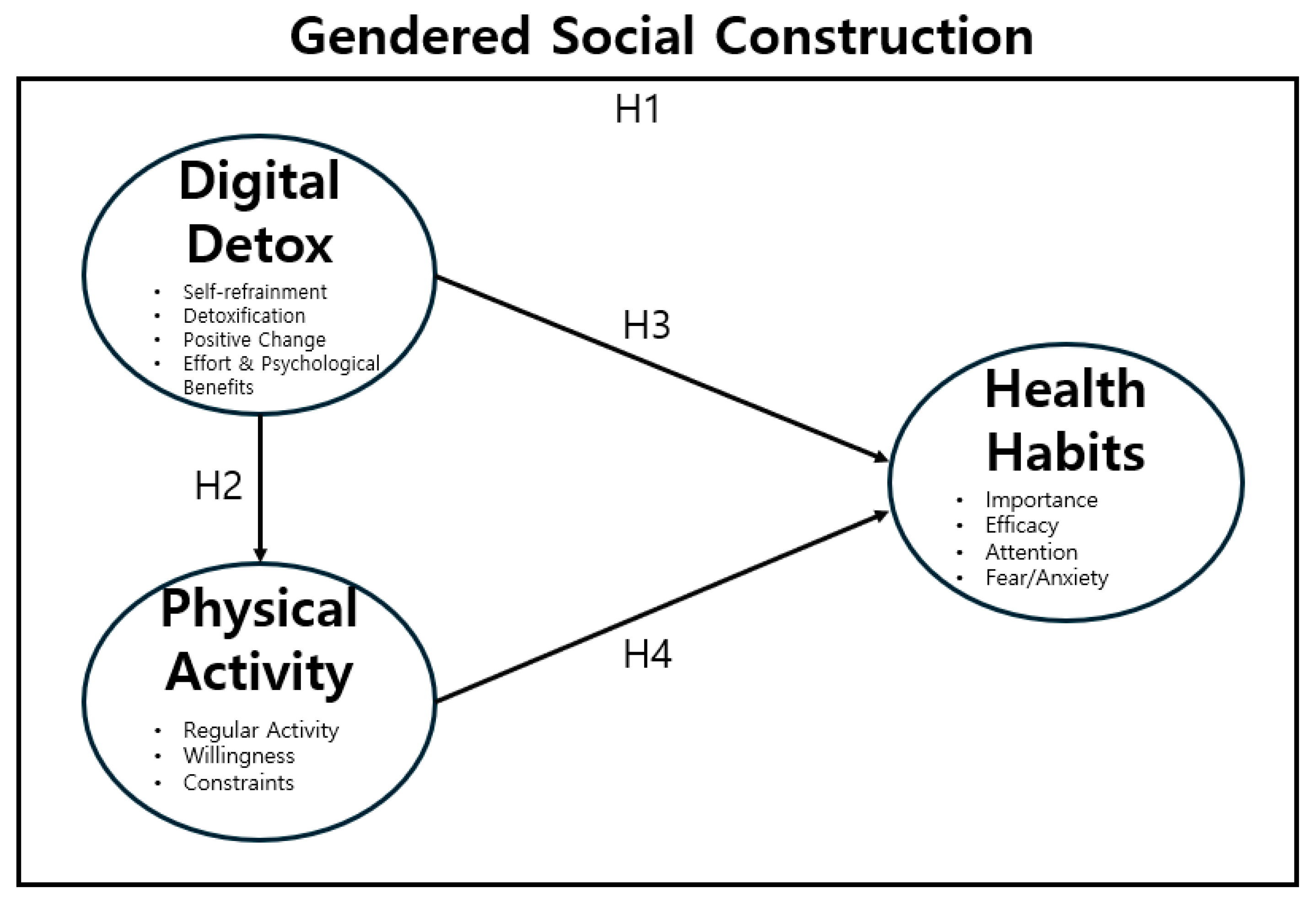

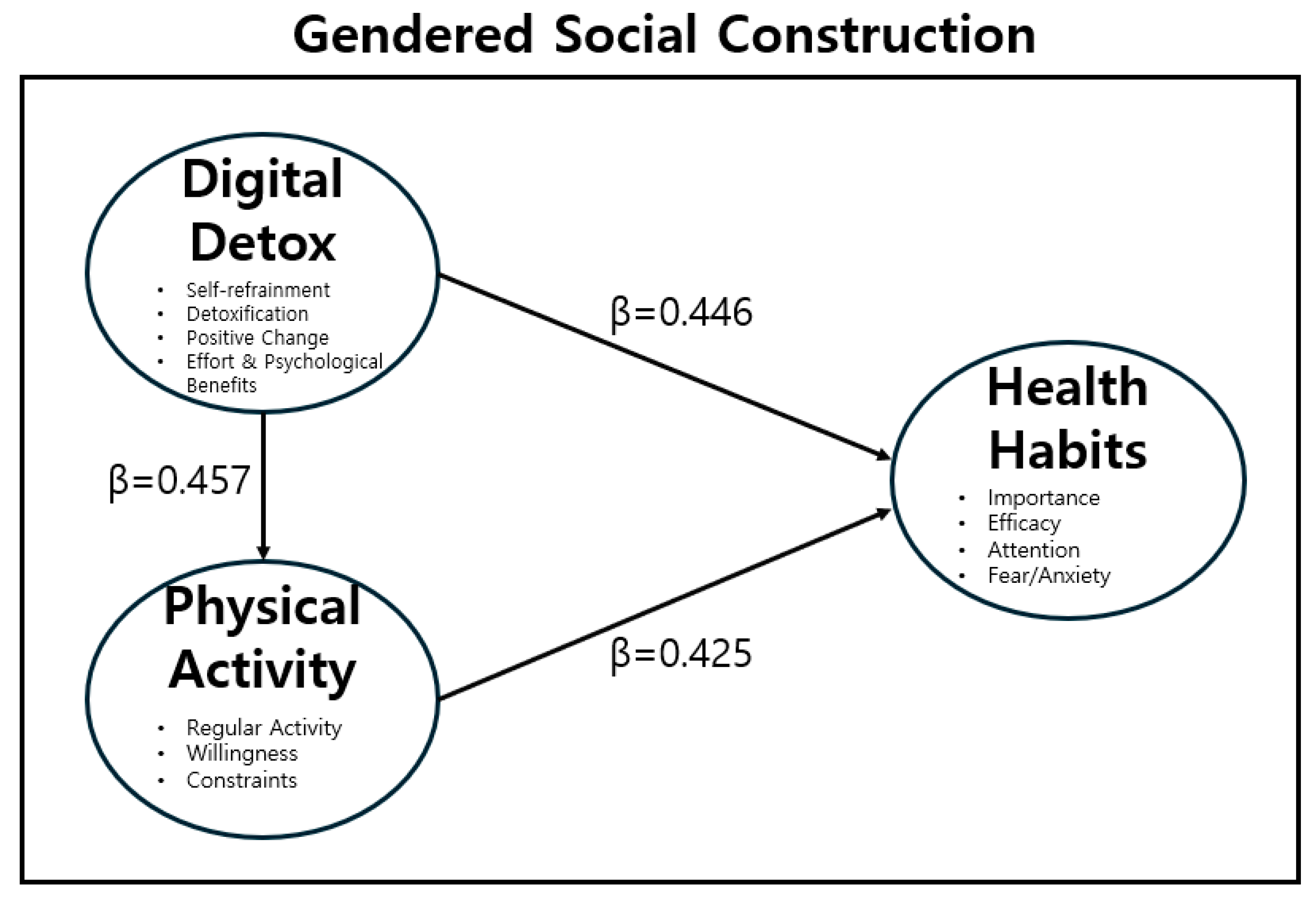

This study examined gender differences in digital detox and physical activity to explore ways of improving health habits among adolescents and to provide foundational data for designing effective health promotion programs. To achieve this, an online survey was conducted in February 2025 with 652 Korean adolescents. Based on the results derived from this process, the discussion is presented in two parts: first, an interpretation of the findings, and second, the practical implications of this study.

4.1. Interpretation of the Findings

This study analyzed gender differences across three domains—digital detox, physical activity, and health habit improvement—and found results that both align with prior research and offer new insights.

First, in the domain of digital detox, female students scored significantly higher on the “Positive Change” factor than their male counterparts. This result suggests that female adolescents may be more attuned to the negative effects of digital device use and more inclined to engage in self-regulation and detox practices. This finding supports Salepaki et al. (2025) [

25], who reported that although women experienced greater psychological resistance to distancing themselves from mobile devices, they also demonstrated heightened awareness of the need for digital detoxification. In essence, female students appeared more likely to practice detox behaviors through self-discipline and reflexivity in digital environments. However, the absence of gender differences in factors such as “Self-refrainment”, “Detoxification”, and “Effort & Psychological Benefits” points to a possible gap between awareness and actual behavior. This suggests that digital detox is influenced not only by individual willpower but also by broader social factors, including peer culture, academic pressure, and social media identity management.

Second, male students reported significantly higher levels of regular physical activity and willingness to engage in such activities compared to female students. These findings are consistent with previous research [

26,

27], highlighting how adolescent physical activity levels are shaped by gender-based cultural expectations, school-based opportunities, and body image-related social norms [

28]. Lower participation among female adolescents cannot be attributed solely to biological differences; rather, it may reflect the influence of gendered embodiment. For instance, social norms that frame high activity levels as “unfeminine” may diminish female students’ self-efficacy and willingness to participate in physical activity. Thus, gender disparities in adolescent physical activity should be understood within structural contexts—such as the gendered organization of physical education, expectations from peers and teachers, and internalized body image concerns.

Third, in the domain of health habit improvement, male students exhibited higher levels of health efficacy, fear, and anxiety, while no significant gender differences emerged in health importance and attention. This suggests that male adolescents may be more responsive to health-related risks in terms of efficacy and concern, whereas everyday attentiveness and general health awareness appear gender-neutral. However, as previous studies have noted [

28,

29], gender differences in health behavior vary depending on the specific subdimensions examined. Research on positive health behaviors (e.g., nutrition, exercise, self-care) often finds higher engagement among females, while studies on health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking) report higher prevalence among males.

These complexities indicate that a single behavioral index cannot capture adolescent health practices and must be interpreted within sociocultural, emotional, and perceptual contexts. This study emphasized that adolescents’ approaches to health in a digital environment are constructed differently according to gender. These differences call for a more nuanced analysis beyond binary gender distinctions, one that considers gender performativity and the positionality of adolescents as social actors. Future research should adopt a multilayered analytical approach, integrating additional contextual factors such as socioeconomic background, community resources, and family environment.

This study also examined the effects of four components of digital detox—“Self-refrainment”, “Detoxification”, “Positive Change”, and “Effort & Psychological Benefits”—on adolescents’ health habit improvement, specifically health importance, health efficacy, health attention, and health-related fear and anxiety. The findings suggest that digital detox is a multidimensional and, at times, conflicting form of social action.

First, “Detoxification” and “Positive Change” positively influenced adolescents’ perception of health importance, while “Effort & Psychological Benefits” had a negative effect. This partially aligns with Chotpitayasunondh & Douglas [

30], who found that voluntary digital media regulation enhances self-awareness and attention to health. Successfully limiting digital use may prompt cognitive reflection, leading to a reconfiguration of health values. However, the negative impact of “Effort & Psychological Benefits” aligns with Nasir et al. (2025) [

31], who noted that detoxing can cause isolation, anxiety, and fear of missing out, leading to emotional exhaustion. Thus, disconnecting from digital devices may instill fear of losing social ties, weakening or defensively reshaping health perceptions.

Second, “Detoxification” and “Effort & Psychological Benefits” positively influenced adolescents’ health efficacy. This supports Radke et al. (2022) [

10], who demonstrated that reducing smartphone use enhances self-control and self-efficacy, reinforcing self-directed health behaviors. Emotional experiences tied to “Effort & Psychological Benefits” also promoted efficacy, suggesting that emotion-driven self-regulation motivates healthy behaviors. This highlights the importance of emotional motivation over mere suppression or instruction in promoting healthy practices. However, “Self-refrainment” and “Positive Change” did not significantly affect efficacy, diverging from Gökçearslan et al. (2016) [

32], who linked self-control over smartphone use with self-efficacy. In this study, voluntary restraint alone did not yield a sense of efficacy, suggesting that contextual support and structured routines are more vital than restraint itself.

Third, regarding “Health Attention”, “Self-refrainment”, “Positive Change”, and “Effort and Psychological Benefits” demonstrated positive effects, whereas “Detoxification” had no significant impact. This finding aligns with Coyne & Woodruff (2023) [

33], who found that digital detox fostered internal awareness, improved bodily perception, and heightened sensitivity to daily routine changes. The lack of significance for “Detoxification” suggests that structural digital restrictions alone may not be sufficient to shift health awareness. Instead, emotional internalization and self-subjectivation are more effective in motivating adolescent health behaviors than mechanical restriction.

Fourth, regarding fear and anxiety, “Effort & Psychological Benefits” had a positive effect, while “Detoxification” had a negative one. This reflects the ambivalence of digital detox: emotional and psychological gains may raise constructive health anxiety and vigilance, yet disconnection can also provoke excessive threat sensitivity or avoidance. This is consistent with Orben et al.’s (2022) [

34] theory of digital exclusion, which argues that disconnecting can deprive adolescents of access to information, health content, and online support, thereby amplifying negative health anxieties. In summary, digital detox can generate dual psychological states in adolescents who are deeply embedded in digital connection and information networks. It functions at the intersection of self-discipline and self-care in youth health practices. While this study’s findings broadly align with the existing literature, they also highlight the emotional tensions and negative reactions that may arise during detox. Therefore, future digital detox programs should foster autonomy, provide emotional support, and help adolescents restore social connections.

It is crucial to address the underlying debate regarding the application of digital detox models to the current generation. For today’s adolescents, digital media serve as an essential, non-negotiable tool for leisure, academic achievement, and social identity formation. Consequently, advocating for a reduction in screen time “at any cost” may be unrealistic and potentially harmful, as it risks imposing a lifestyle standard from previous, digitally unconnected generations onto youth whose environments are fundamentally saturated with technology.

This critical perspective suggests that the focus should shift from blanket reduction to fostering mindful and meaningful digital engagement. Instead of only focusing on the negative impacts of overuse, health promotion strategies must recognize digital media as a potential aid for desirable health behaviors. Specifically, digital platforms can be leveraged as crucial tools for health action, such as accessing reliable health information, using fitness tracker applications for regular physical activity, utilizing stress management apps, or participating in online psychological support groups. This enables adolescents to integrate digital tools into a balanced, self-directed healthy lifestyle.

Although certain predictors showed statistically significant associations with health anxiety, the overall explanatory power (R2) of the model for this outcome was notably low. This implies that other critical factors influencing adolescents’ health anxiety were not considered in the current model. Hence, caution should be exercised when interpreting these findings, and the observed effects should be considered statistically significant but small in substantive magnitude. Future studies should aim to identify and incorporate additional variables to enhance the explanatory capacity of the models. One possible reason for the low explanatory power is the multidimensional nature of health anxiety, which may not be sufficiently captured by behavioral variables such as digital detox or physical activity alone. For example, emotional regulation difficulties, underlying mental health issues, or social stressors (e.g., academic competition, peer surveillance, family instability) may play a larger role but were not included in this study’s framework. In addition, some predictors may have demonstrated weak or inconsistent effects due to their conditional influence. For instance, voluntary digital detox may enhance health perception in structured settings but fail to do so in socially disconnected environments, thereby diluting its average effect. Likewise, the impact of physical constraints may differ across individuals depending on how they interpret or internalize these experiences. These findings suggest the need for more contextualized models that incorporate psychological, environmental, and relational factors to better understand adolescent health anxiety. Future studies should consider integrating variables such as emotional well-being, perceived social support, and stress-coping strategies to enhance explanatory capacity.

Finally, this study analyzed how the three factors of physical activity—regular physical activity, willingness to engage, and physical constraints—affected adolescents’ health habit improvement. The results partially align with previous studies while revealing some noteworthy distinctions. Only willingness significantly influenced adolescents’ perception of health importance; actual behavior (regular activity) and constraints had no significant effect. This supports Dishman et al. (2004) [

35], who emphasized the centrality of intentional factors in shaping adolescent health values and autonomy. Adolescents appear to recognize the importance of health more through internal motivation and meaning-making than through the frequency of their activities, aligning with Ryan & Deci’s (2000) [

36] Self-Determination Theory, which posits that internal motivation and value internalization—rather than external performance—more strongly influence sustained engagement and attitudes toward health. In short, “Willingness to Act” serves as a key psychosocial resource that shapes perceptions of health importance, outweighing actual participation or external barriers.

Regarding health efficacy, both regular activity and willingness had positive effects, while constraints had a negative effect. These findings support Bandura’s (1997) [

37] Self-Efficacy Theory, which highlights enactive mastery—the actual performance of behavior—as fundamental to developing self-efficacy. Engaging in physical activity directly fosters a sense of control and self-management of health behaviors. Conversely, the negative impact of physical constraints is consistent with Sallis et al. (2000) [

20], who identified structural barriers, such as a lack of time, space, and social support, as major deterrents to adolescent activity. These obstacles can undermine self-efficacy, reinforcing a structuralist view that highlights how social and environmental contexts shape health behaviors beyond individual intent.

In terms of health attention, all three factors—regular activity, willingness, and constraints—had positive effects, with willingness being the most influential. Interestingly, constraints also had a positive impact, partially diverging from prior research but aligning with Bélanger et al. (2011) [

38], who found a link between adolescent physical activity and health awareness, information-seeking, and self-monitoring. The unexpected positive role of constraints suggests that barriers may provoke reflection on one’s health, increasing awareness. Adolescents who are restricted from engaging in physical activity may become more conscious of their health status. This interpretation aligns with a social constructionist view, which sees health practices not simply as behaviors but as being shaped by social interactions and discourses around opportunity and limitation.

The most striking finding was that, for health-related fear and anxiety, only “Physical Constraints” had a significant positive effect; neither regular activity nor willingness demonstrated influence. This aligns with prior studies illustrating that negative experiences or limitations more strongly impact health-related anxiety. For example, Weems et al. (2010) [

39] found that adolescents with physical limitations displayed heightened health sensitivity and anxiety. Restrictions or experiences of being unwell can trigger emotional responses and awareness of health risks, echoing Beck’s (1992) [

40] Risk Society Theory, which frames health anxiety as socially constructed. In this light, high activity levels do not necessarily reduce anxiety; instead, constraints and interruptions may heighten awareness of health vulnerability and loss, intensifying anxiety.

In summary, this study revealed that adolescents’ health habits are shaped more by their perception, enactment, and interpretation of experiences—including constraints—than by the frequency of physical activity. Physical activity emerges not as a mere behavioral act but as a meaning-rich social practice intertwined with identity, emotion, and social context. Therefore, adolescent health promotion policies should move beyond encouraging activity alone. They should foster internal motivation, offer psychological support for overcoming constraints, and address structural barriers simultaneously.

4.2. Practical Implications of This Study

This study conducted a multilayered analysis of how adolescents’ digital detox practices and physical activity influenced health habit improvement, considering both gender- and factor-based differences. It offers the following practical implications.

First, the findings highlight the need for gender-sensitive health education and intervention strategies. Female students showed greater sensitivity to the negative effects of digital device use and a stronger awareness of the need for detoxification, while male students demonstrated higher participation and willingness in physical activity. These results suggest that adolescent health behaviors are shaped within gendered social contexts and require tailored interventions reflecting sex-specific motivations, constraints, and perceptions of health education and digital detox programs.

Second, the ambivalent effects of digital detox on health habits must be acknowledged. While factors such as “Detoxification” and “Positive Change” positively influenced health awareness and efficacy, “Effort & Psychological Benefits” negatively impacted perceptions due to emotional exhaustion, implying that digital detox strategies should not rely solely on restriction but must include emotional support and peer-based solidarity. Crucially, schools and communities should move beyond punitive restriction programs and instead implement comprehensive digital literacy education and health-oriented media utilization programs. These programs should teach mindful digital engagement, emphasizing how to leverage digital tools (e.g., fitness trackers, health apps) as aids to promote positive physical activity and mental wellness. This approach promotes autonomy, stimulates intrinsic motivation, and fosters collective engagement.

Third, this study confirms that the quality of physical activity experiences and willingness to participate are central to improving adolescents’ health habits. Notably, willingness had a stronger impact than frequency of activity, indicating that internal motivation and personal meaning are more influential than mere participation. Consequently, school physical education should prioritize self-determination and student choice by offering participatory, experiential activities that empower adolescents as active agents in their health practices.

Fourth, the ambivalent role of perceived constraints should be recognized, with support offered to help adolescents transform them into proactive practices. While physical constraints may lower self-efficacy and increase anxiety, they can also enhance self-reflection and health awareness. Thus, rather than promoting exercise alone, schools should implement psychological support, improve environmental conditions, and adopt socially responsive physical education approaches for students facing limitations.

Fifth, the findings provide a crucial basis for developing data-driven, customized intervention strategies tailored according to gender and behavioral factors. Given that digital detox and physical activity were found to operate independently (i.e., the path between them was not significant), policy efforts should focus on separate, targeted support. Specifically, for female adolescents, programs should address the gap between their high awareness of the need for digital detox and their actual practice; strategies must focus on group-based detox activities that provide social and emotional support to mitigate the fear of missing out (FoMO) and isolation, while promoting autonomy in self-regulation. Conversely, for male adolescents, whose engagement in physical activity is higher, interventions should aim to consolidate this activity into greater health efficacy; this can be achieved through achievement-based activities and structured performance goals that reinforce their sense of control over their health behaviors.

This study examined how digital detox and physical activity influence adolescents’ health habits, with attention to gender differences and sociocultural contexts. While the findings are meaningful, several limitations should be noted, and future research directions are suggested accordingly. First, the use of quota sampling without an a priori power analysis limits the representativeness and generalizability of the findings. Future studies should adopt probability sampling and a more robust sample design to improve statistical validity. Second, some regression models showed relatively low explanatory power, suggesting the influence of unmeasured variables. Future research should incorporate key factors, including baseline health status, health literacy, and prior participation in sports, and employ advanced methods such as structural equation modeling to enhance understanding. Third, some items of the Digital Detox scale were modified or newly developed. Additional validation studies are needed to ensure the reliability and construct validity of the measurement tool across diverse populations.