Establishing Psychometric Properties of the Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instrumentation

2.1.1. Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument (Modified BTCPI)

2.1.2. Participant Demographic Questionnaire

2.1.3. Data Cleaning and Procedures

2.2. Data Analysis

2.2.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

2.2.2. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling

2.2.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

2.2.4. Validation Analysis of the Modified Scale

2.2.5. Multi-Group Invariance Analysis

3. Results

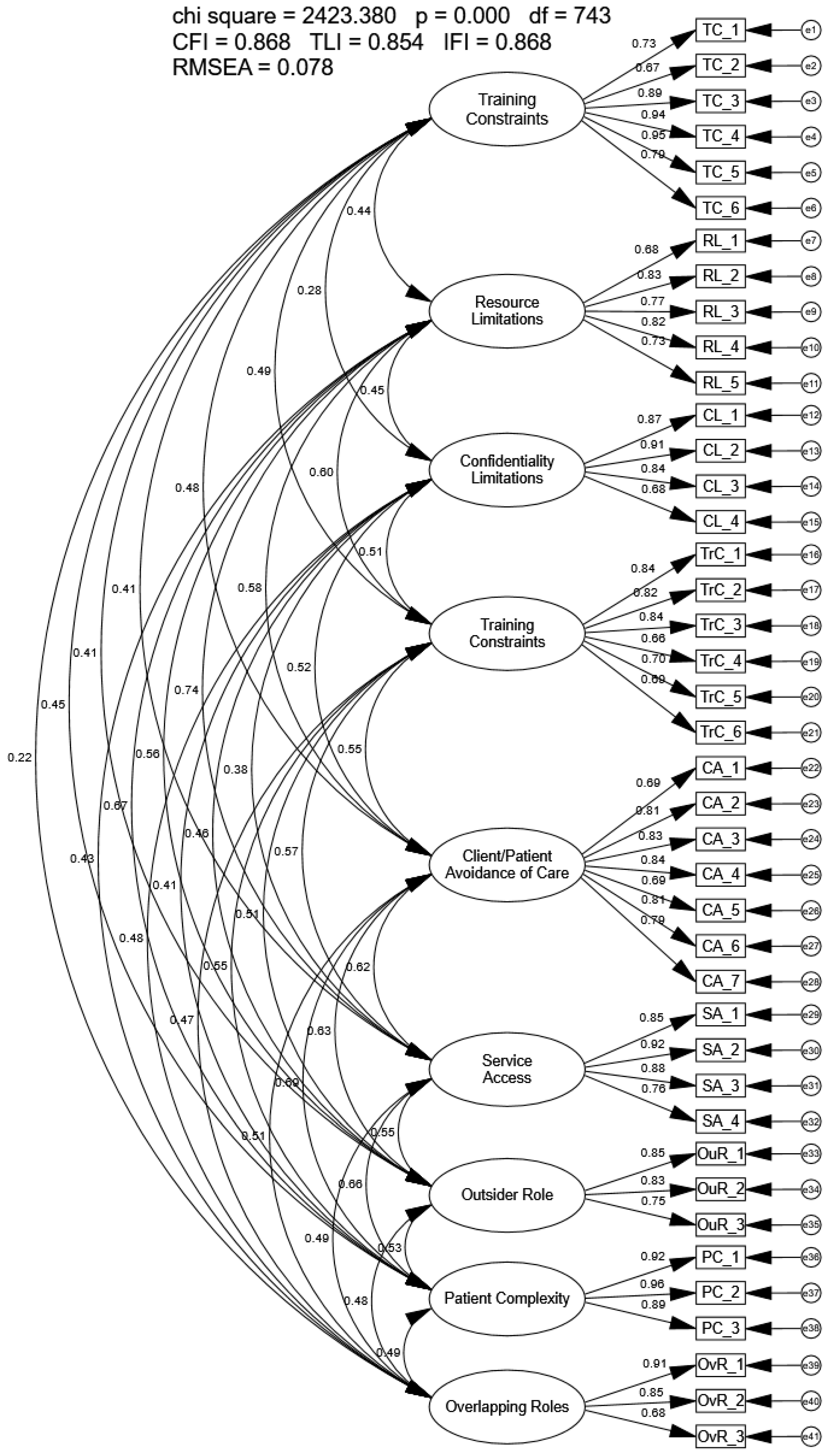

3.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

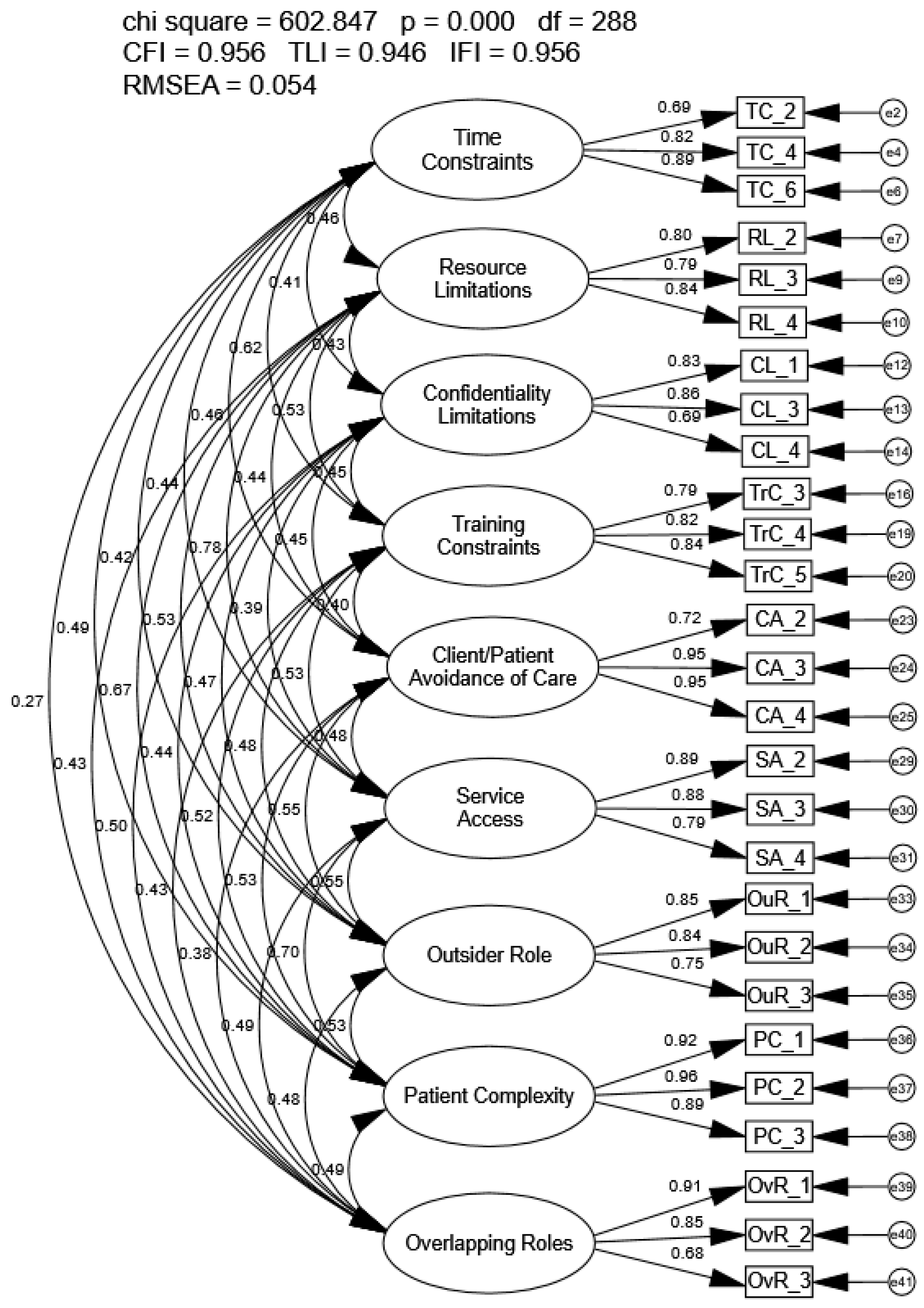

3.2. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

3.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis

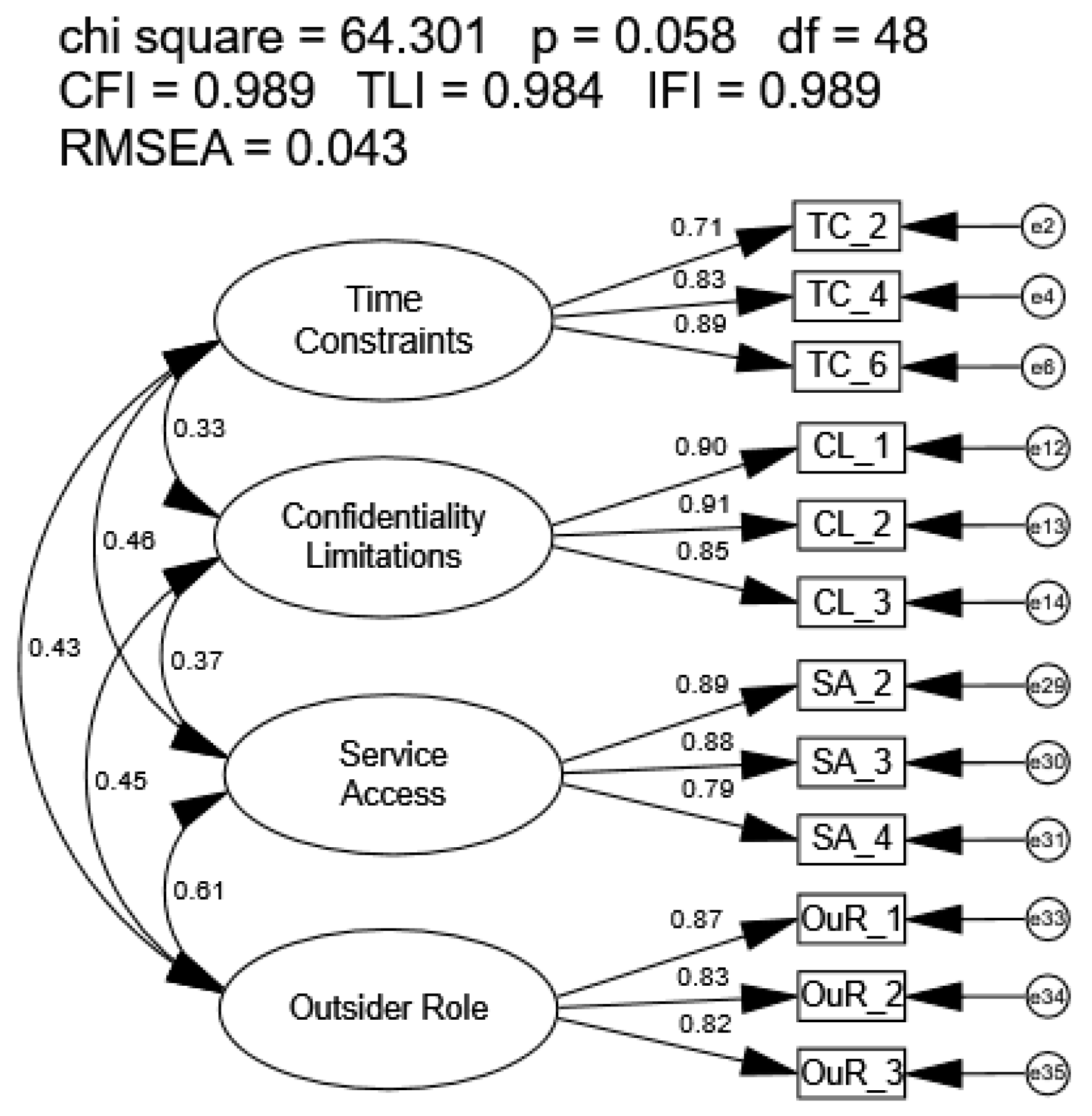

3.4. Validation of the Refined Barriers to Providing Optimal Care Model

3.5. Multi-Group Invariance Testing

3.5.1. Years of Practice

3.5.2. Profession

3.5.3. Rurality

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychometric Analysis

4.1.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.1.2. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

4.1.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Validation of the Identified Model

4.2. Multi-Group Invariance Testing

4.2.1. Years of Experience Groups

4.2.2. Provider Groups

4.2.3. Rurality Groups

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Farrigan, T.; Genetin, B.; Sanders, A.; Pender, J.; Thomas, K.L.; Winkler, R.; Cromartie, J. Rural America at a Glance; Report No. EIB-282; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brems, C.; Johnson, M.E.; Warner, T.D.; Roberts, L.W. Barriers to Healthcare as Reported by Rural and Urban Interprofessional Providers. J. Interprof. Care 2006, 20, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, A.A.; McCurry, A.D.; Tesnohlidek, L.A.; Kearsley, B.K.; Hansen-Oja, M.L.; Glivar, G.C.; Ward, A.M.; Craig, K.J.; Chung, E.B.; Smith, S.J.; et al. Barriers to Providing Optimal Care in Idaho from the Perspective of Healthcare Providers: A Descriptive Analysis. Healthcare 2025, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyr, M.E.; Etchin, A.G.; Guthrie, B.J.; Benneyan, J.C. Access to Specialty Healthcare in Urban versus Rural U.S. Populations: A Systematic Literature Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosar, C.M.; Loomer, L.; Ferdows, N.B.; Trivedi, A.N.; Panagiotou, O.A.; Rahman, M. Assessment of Rural-Urban Differences in Postacute Care Utilization and Outcomes Among Older US Adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1918738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.C.; Rossen, L.M.; Matthews, K.; Guy, G.; Trivers, K.F.; Thomas, C.C.; Schieb, L.; Lademarco, M.F. Preventable Premature Deaths from the Five Leading Causes of Death in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties, United States, 2010–2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2024, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, E.; Ullrich, F.; Baten, R.B.A.; Shrestha, M.; Mueller, K.; RUPRI Center for Rural Health Policy Analysis; Rural Health Research & Policy Centers; Rural Policy Research Institute. Health Care Professional Workforce Composition Before and After Rural Hospital Closure; Rural Policy Research Institute: Iowa City, Iowa, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bethea, A.; Samanta, D.; Kali, M.; Lucente, F.C.; Richmond, B.K. The Impact of Burnout Syndrome on Practitioners Working within Rural Healthcare Systems. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, J.M.; Abshire, D.A.; Alejandro, A.G. System- and Individual-Level Barriers to Accessing Medical Care Services Across the Rural-Urban Spectrum, Washington State. Health Serv. Insights 2022, 15, 11786329221104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. Indianap. Indiana 2014, 17, 161–190. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, L.E.; Ten Klooster, P.M. Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling: Practical Guidelines and Tutorial with a Convenient Online Tool for Mplus. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 795672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, N.L.; Barrett, K.C.; Morgan, G.A. IBM SPSS for Intermediate Statistics: Use and Interpretation, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pesudovs, K.; Burr, J.M.; Harley, C.; Elliott, D.B. The Development, Assessment, and Selection of Questionnaires. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2007, 84, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers, A.S.; Sanford, K.; Brewington, M.; Buchanan, A. Development of a New Measure of Encounters with Health Care Barriers: The Commonly Experienced Health Care Barriers Index. Psychol. Assess. 2024, 36, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly-Shah, V.N. Factors Influencing Healthcare Provider Respondent Fatigue Answering a Globally Administered In-App Survey. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abay, K.A.; Berhane, G.; Hoddinott, J.; Tafere, K. Respondent Fatigue Reduces Dietary Diversity Scores Reported from Mobile Phone Surveys in Ethiopia during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 2269–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhry, N.K.; Fletcher, R.H.; Soumerai, S.B. Systematic Review: The Relationship between Clinical Experience and Quality of Health Care. Ann. Intern. Med. 2005, 142, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P. Relationship Between Nurse Certification and Clinical Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2020, 35, E1–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reule, S.; Foley, R.; Shaughnessy, D.; Drawz, P.; Ishani, A.; Rosenberg, M. Does Experience Matter? The Relationship between Nephrologist Characteristics and End Stage Kidney Disease Patient Outcomes. Hemodial. Int. 2021, 1, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youngcharoen, P.; Aree-Ue, S. A Cross-Sectional Study of Factors Associated with Nurses’ Postoperative Pain Management Practices for Older Patients. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Kajiwara, Y.; Morimoto, M. Factors Influencing Pain Management Practices Among Nurses in University Hospitals in Western Japan: A Cross-Sectional Study Using Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2025, 27, e70143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Bitton, A.; Tu, S.-P.; Plews-Ogan, M.; Horowitz, K.R.; Schwartz, M.D. The End of the 15–20 Minute Primary Care Visit. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1584–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, S.; Golberstein, E.; Huang, T.-Y.; Satin, D.J.; Smith, L.B. Docs with Their Eyes on the Clock? The Effect of Time Pressures on Primary Care Productivity. J. Health Econ. 2021, 77, 102442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donahue, K.E.; Ashkin, E.; Pathman, D.E. Length of Patient-Physician Relationship and Patients’ Satisfaction and Preventive Service Use in the Rural South: A Cross-Sectional Telephone Study. BMC Fam. Pract. 2005, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitnux. Travel Nurse Statistics. Gitnux Market Data Reports, 2024. Available online: https://gitnux.org/travel-nurse-statistics/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Skillman, S.M.; Palazzo, L.; Keepnews, D.; Hart, L.G. Characteristics of Registered Nurses in Rural Versus Urban Areas: Implications for Strategies to Alleviate Nursing Shortages in the United States. J. Rural Health 2006, 22, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A.; Fridlund, B.; De Geest, S.; Mårtensson, J.; Moons, P.; Norekval, T.M.; Smith, K.; Steinke, E.; Thompson, D.R.; et al. Sexual Counselling of Cardiac Patients: Nurses’ Perception of Practice, Responsibility and Confidence. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2010, 9, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansink, R.; Braspenning, J.; van der Weijden, T.; Elwyn, G.; Grol, R. Primary Care Nurses Struggle with Lifestyle Counseling in Diabetes Care: A Qualitative Analysis. BMC Fam. Pract. 2010, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willaing, I.; Ladelund, S. Nurse Counseling of Patients with an Overconsumption of Alcohol. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2005, 37, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbrook, J.I.; Duffield, C.; Li, L.; Creswick, N.J. How Much Time Do Nurses Have for Patients? A Longitudinal Study Quantifying Hospital Nurses’ Patterns of Task Time Distribution and Interactions with Health Professionals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2011, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussault, G.; Franceschini, M.C. Not Enough There, Too Many Here: Understanding Geographical Imbalances in the Distribution of the Health Workforce. Hum. Resour. Health 2006, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzer, M.; Manwell, L.B.; Williams, E.S.; Bobula, J.A.; Brown, R.L.; Varkey, A.B.; Man, B.; McMurray, J.E.; Maguire, A.; Horner-Ibler, B.; et al. Working Conditions in Primary Care: Physician Reactions and Care Quality. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsky, C.; Colligan, L.; Li, L.; Prgomet, M.; Reynolds, S.; Goeders, L.; Westbrook, J.; Tutty, M.; Blike, G. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice: A Time and Motion Study in Four Specialties. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Supply and Distribution of the Primary Care Workforce in Rural America: 2019. Available online: https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/rhrc/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/06/RHRC_PB167_Larson.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Grumbach, K.; Vranizan, K.; Bindman, A.B. Physician Supply and Access to Care in Urban Communities. Health Aff. 1997, 16, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K.; Horowitz, J.M.; Brown, A.; Fry, R.; Cohn, D.; Igielnik, R. Demographic and Economic Trends in Urban, Suburban and Rural Communities. Pew Research Center. 2018. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/05/22/demographic-and-economic-trends-in-urban-suburban-and-rural-communities/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tolbert, J.; Cervantes, S.; Bell, C.; Damico, A. Key Facts About the Uninsured Population. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2024. Available online: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Smalley, K.S.; Warren, J.C.; Rainy, J.P. Rural Mental Health: Issues, Policies, and Best Practices; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, D.G.; Shipman, S.A.; Pollack, S.W.; Andrilla, C.H.A.; Schmitz, D.; Evans, D.V.; Peterson, L.E.; Longenecker, R. Growing a Rural Family Physician Workforce: The Contributions of Rural Background and Rural Place of Residency Training. Health Serv. Res. 2024, 59, e14168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, C.; Burns, S.; Lobo, R. Managing Qualitative Research as Insider-Research in Small Rural Communities. Rural Remote Health 2018, 18, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Idaho Workforce Nursing Center. The Idaho Nursing Workforce 2024 Report on Current Supply, Education and Employment Demand Projections. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/nursing-network/production/files/32341/original/The_Idaho_Nursing_Workforce_2018_report.pdf?1541307222 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Dahal, A.; Skillman, S.M. Idaho’s Physician Workforce in 2021. Center for Health Workforce Studies. Available online: https://familymedicine.uw.edu/chws/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2022/08/Idaho_Physicians_FR_July_2022.pdf (accessed on 3 February 2025).

| Demographic Characteristics | Number of Participants | Percentage of Participants (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Profession | ||

| Nurse (e.g., RN) | 115 | 30.8 |

| Physician (i.e., MD/DO) | 62 | 16.6 |

| Physician Assistant (i.e., PA) | 22 | 5.9 |

| Nurse Practitioner (i.e., NP) | 13 | 3.5 |

| Social Worker (e.g., LCSW) | 7 | 1.9 |

| Pharmacist (i.e., PharmD) | 6 | 1.6 |

| Other * | 134 | 35.9 |

| Unknown | 8 | 2.1 |

| Years of Clinical Practice | ||

| ≤10 years | 172 | 46.1 |

| ≥11 years | 180 | 48.3 |

| Unknown | 21 | 5.6 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 272 | 72.9 |

| Male | 91 | 24.4 |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 | 0.5 |

| Unknown | 8 | 2.1 |

| Race or Ethnicity | ||

| White | 311 | 83.4 |

| Hispanic or Latino or Spanish Origin | 33 | 8.8 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 7 | 1.9 |

| Black or African American | 3 | 0.8 |

| Asian | 5 | 1.3 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 3 | 0.8 |

| Other | 5 | 1.3 |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 | 3.2 |

| Item | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA_2 | 0.913 | |||

| SA_3 | 0.905 | |||

| SA_4 | 0.702 | |||

| CL_2 | −0.959 | |||

| CL_1 | −0.827 | |||

| CL_3 | −0.762 | |||

| TC_6 | 0.841 | |||

| TC_4 | 0.817 | |||

| TC_2 | 0.693 | |||

| OuR_3 | −0.942 | |||

| OuR_1 | −0.725 | |||

| OuR_2 | −0.612 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 4.873 | 1.679 | 1.554 | 1.318 |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.884 | 0.891 | 0.834 | 0.816 |

| Omega | 0.886 | 0.892 | 0.845 | 0.826 |

| χ2 | df | χ2diff (dfdiff) | CFI | CFIdiff | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤10 (n = 172) | 86.79 | 48 | — | 0.972 | — | 0.961 | 0.972 | 0.069 |

| ≥11 (n = 180) | 50.10 | 48 | — | 0.998 | — | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.016 |

| Configural Model (equal form) | 136.90 | 96 | — | 0.984 | — | 0.978 | 0.984 | 0.035 |

| Metric Model (equal loadings) | 140.00 | 104 | 3.10 (8) | 0.986 | 0.002 | 0.982 | 0.986 | 0.031 |

| Equal Factor Variances Model | 175.23 | 111 | 38.33 (15) | 0.975 | 0.009 | 0.970 | 0.975 | 0.041 |

| Scalar Model (equal indicator intercepts) | 149.45 | 112 | 12.55 (16) | 0.985 | 0.001 | 0.983 | 0.985 | 0.031 |

| Equal Latent Means Model | 166.51 | 116 | 29.61 (20) | 0.980 | 0.004 | 0.977 | 0.980 | 0.035 |

| χ2 | df | χ2diff (dfdiff) | CFI | CFIdiff | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD/DO/NP/PA (n = 97) | 57.99 | 48 | — | 0.984 | — | 0.977 | 0.984 | 0.047 |

| Nurse (n = 115) | 57.02 | 48 | — | 0.982 | — | 0.982 | 0.987 | 0.041 |

| Configural Model (equal form) | 115.02 | 96 | — | 0.985 | — | 0.980 | 0.986 | 0.031 |

| Metric Model (equal loadings) | 125.98 | 104 | 10.96 (8) | 0.983 | 0.002 | 0.978 | 0.983 | 0.032 |

| Equal Factor Variances Model | 147.53 | 111 | 32.51 (15) | 0.971 | 0.014 | 0.966 | 0.972 | 0.040 |

| Scalar Model (equal indicator intercepts) | 141.51 | 112 | 26.49 (16) | 0.977 | 0.008 | 0.973 | 0.977 | 0.035 |

| Equal Latent Means Model | 168.73 | 116 | 53.71 (20) | 0.959 | 0.026 | 0.953 | 0.959 | 0.047 |

| χ2 | df | χ2diff (dfdiff) | CFI | CFIdiff | TLI | IFI | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4999 (n = 97) | 65.41 | 48 | — | 0.991 | — | 0.988 | 0.991 | 0.036 |

| >5000 (n = 115) | 57.03 | 48 | — | 0.985 | — | 0.979 | 0.985 | 0.048 |

| Configural Model (equal form) | 122.69 | 96 | — | 0.990 | — | 0.986 | 0.990 | 0.028 |

| Metric Model (equal loadings) | 131.21 | 104 | 8.52 (8) | 0.989 | 0.001 | 0.987 | 0.990 | 0.027 |

| Equal Factor Variances Model | 178.17 | 111 | 55.48 (15) | 0.974 | 0.016 | 0.974 | 0.974 | 0.041 |

| Scalar Model (equal indicator intercepts) | 142.72 | 112 | 20.03 (16) | 0.988 | 0.002 | 0.986 | 0.988 | 0.027 |

| Equal Latent Means Model | 205.02 | 116 | 82.33 (20) | 0.966 | 0.024 | 0.961 | 0.966 | 0.046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alomar, T.O.; Glivar, G.C.; Chung, E.B.; Craig, K.J.; Ward, A.M.; Dingel, A.J.; Kearsley, B.K.; Goodwin, J.R.; McCurry, A.D.; Casanova, M.P.; et al. Establishing Psychometric Properties of the Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument. Healthcare 2026, 14, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010102

Alomar TO, Glivar GC, Chung EB, Craig KJ, Ward AM, Dingel AJ, Kearsley BK, Goodwin JR, McCurry AD, Casanova MP, et al. Establishing Psychometric Properties of the Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlomar, Tabarak O., Gillian C. Glivar, Eva B. Chung, Kathryn J. Craig, Allie M. Ward, Audrey J. Dingel, B. Kelton Kearsley, Jake R. Goodwin, Allie D. McCurry, Madeline P. Casanova, and et al. 2026. "Establishing Psychometric Properties of the Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010102

APA StyleAlomar, T. O., Glivar, G. C., Chung, E. B., Craig, K. J., Ward, A. M., Dingel, A. J., Kearsley, B. K., Goodwin, J. R., McCurry, A. D., Casanova, M. P., Dluzniewski, A., & Baker, R. T. (2026). Establishing Psychometric Properties of the Modified Barriers Experienced in Providing Healthcare Instrument. Healthcare, 14(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010102