Factors Hindering Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in Afghanistan Under the Taliban Regime: A Qualitative Study with Recommended Solutions †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Approach and Theory

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis and Data Quality

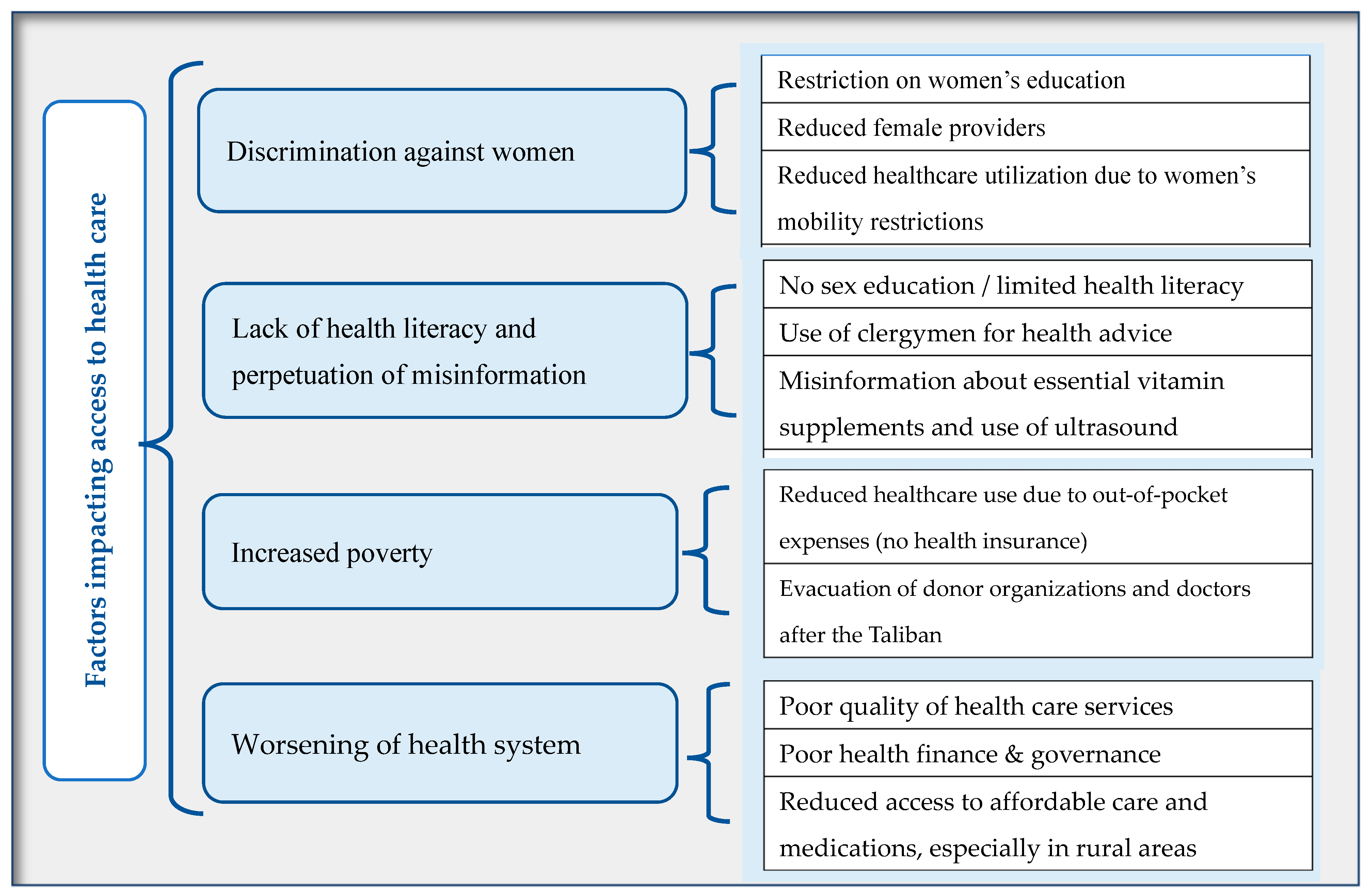

3. Results

3.1. Discrimination Against Women

My friend who lives in Kandahar Providence has got pregnant, but she cannot go to a clinic by herself because, in her village, the Taliban punishes women who are outside without their husbands.

Some women had jobs and could afford to visit a doctor, you know. Now, women are banned from work and from having a job, and even some men also struggle with finding a job because of the worsening of the economy.

I conducted major surgeries and trained new physicians and midwives; however, now I can no longer teach or train because women are banned from educating or receiving an education, but I still practice as a gynecologist.

As a healthcare professional, I am eager to learn new medical procedures and strengthen my skills. Before the Taliban, I used to have the opportunity to travel to other countries like India and Nepal [for training], but now, with the Taliban in power, I do not get those opportunities.

Religion plays a big role. A male doctor cannot touch a female patient. Several patients, especially their husbands do not agree with a male doctor seeing their wives. In a society where women’s education is banned, and future doctors cannot be trained, how could there not be a lack of female healthcare providers, and how could mothers not die?

…These reports show how much maternal health was affected by the Taliban. They, of course, caused an increase in maternal mortality rate because of the lack of access to health services… 81% of midwives claimed that they become harassed by the Taliban [for going to their jobs].

3.2. Lack of Health Literacy and Perpetuation of Misinformation

At least before the Taliban, we could provide free workshops to educate pregnant women…we used to teach women about hygiene, breast cancer, and iron supplements. We used to provide these not only in our hospitals but also in mosques. But now none of those happen or can happen because of the Taliban.

I also hope that there will be more awareness and education about women’s health. Many girls do not know that getting their menstruation cycle is normal. When I first got mine, I cried, and I was scared. There is no education about it at school. I was shy to tell my mother about it, so I told my sister, and she said that it was okay and normal.

Once, I had a patient with high blood pressure who left the hospital right after birth, and when she got home, the family members fed her butter and salty food. She had several heart attacks, and they took her to a Mullah for the day. By nighttime, she went unconscious, and they had to bring her back to the hospital… These types of incidents happen often in Afghanistan.

…Mullahs advise women to visit mosques and see them instead of seeing a doctor. Some of the Mullahs threaten women that if they go to a doctor, something bad may happen to them, and so women get discouraged from going to a doctor, especially if they are uneducated.

We used to publicize this through the media to bring awareness. We also broadcasted health education clips, and this was especially helpful in reaching people in rural areas, but now, with the Taliban, we cannot do any of these things. Women with hypertension need to meet a doctor frequently during pregnancy so that she doesn’t end up with preeclampsia, but unfortunately, now doctor visits are very less likely.

My husband, who is a doctor, and I knew the importance of perinatal care; I would get checkups regularly including ultrasound… but I know several women who did not go to a doctor unless they got severely sick.

3.3. Increased Poverty

Sometimes they [patients] wait to make enough money, let’s say, like 50 Af., and then, they come to the doctor, which is too late, and their health is much worse. Sometimes they do come to doctor, and sometimes they even don’t come to doctor…they just go directly to a pharmacy, and they get the medication from a pharmacist because they do not have money for both medication and doctor.

Before the Taliban, people could afford healthcare, but now the economy is so bad that people do not visit healthcare and instead try to cure themselves at home with home remedies. The cost of medications and lab tests has also risen.

Before the Taliban, people preferred and were able to use private hospitals because private hospitals had better quality of care and services than public hospitals. Public hospitals are also very crowded because they are cheaper; for example, the fee of a visit is 20 Af. vs. in private hospitals, which can be up to 200 Af. … In our hospital, we provide free services two days a week because otherwise, there won’t be enough patients visiting. We also provide a 30% discount. People are more likely to use services when the costs are lower.

3.4. Worsening of the Health System

In public hospitals, women are discharged quickly because of high demand and crowdedness, and in private hospitals, women themselves leave sooner because the longer they stay, the more it will cost [them]. In public hospitals, women have to leave within an hour of delivery. In private hospitals, they usually stay up to 4 h or so.

There are no prenatal checkups because their capacity is so small that if a woman goes there and says, “I need a checkup”, they would laugh at her. They would be like, “We have women here dying because they need care. And you just come here for a checkup, like, you look fine, just go home unless you have a severe problem and it’s like your baby’s coming out”…Also, the facilities are not good. It’s cold, and there are not enough beds.

In public hospitals, there is no system for making appointments. People just show up and stay in line for health services. I saw a woman who kept saying that “the baby is coming, the baby is coming!”, but because she was in the waiting line, there was no bed for her, and the doctors were not paying attention. She gave birth in the hallway, on the cold concrete. There are not enough doctors, so doctors get tired, and when it is their lunchtime, they go to lunch and don’t care if patients are in pain and need the doctor. Some doctors yell at patients, saying if you couldn’t bear the pain, you shouldn’t have gotten pregnant.

Good doctors don’t like to live in rural areas because of poor living conditions, lack of technology, and security issues. Before the Taliban, there were some incentives provided to doctors to work in rural areas. For example, a midwife was paid 7000 a month in Kabul, and in rural areas, they were paid 30,000. Now that the Taliban are here, things have gotten worse. There is no incentive, and women face many obstacles in practicing midwifery.

Before the Taliban, there were some non-profit foreign organizations that were financially supporting the healthcare system; although, because of governmental corruption, not all the benefits reached the beneficiaries. But it was much better than the current situation under the Taliban.

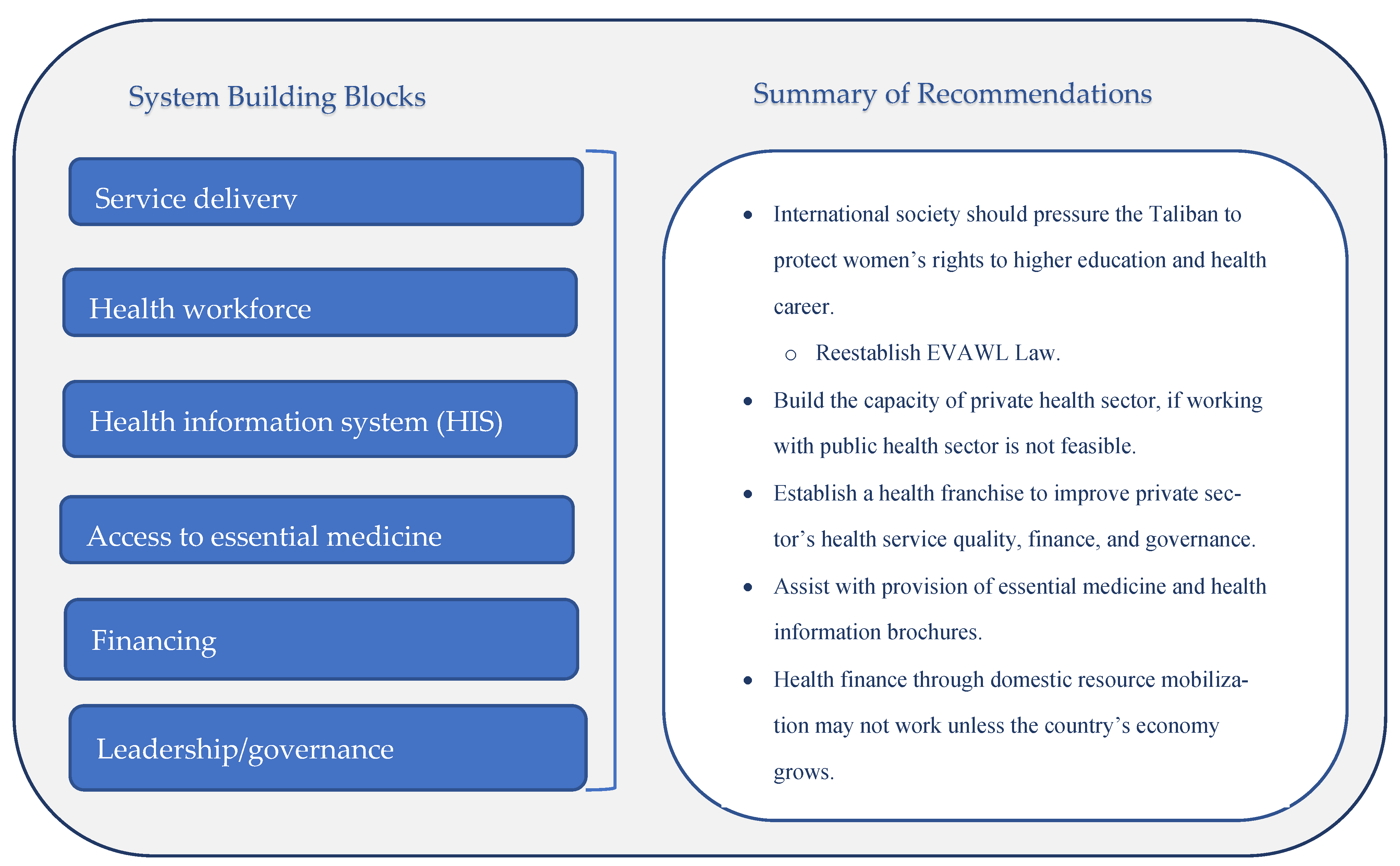

4. Discussion and Recommendations

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Recommended Solutions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nic Carthaigh, N.; De Gryse, B.; Esmati, A.S.; Nizar, B.; Van Overloop, C.; Fricke, R.; Bseiso, J.; Baker, C.; Decroo, T.; Philips, M. Patients struggle to access effective health care due to ongoing violence, distance, costs and health service performance in Afghanistan. Int. Health 2015, 7, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Kim, C.; Archer, L.; Sayedi, O.; Jabarkhil, M.Y.; Sears, K. Assessing the feasibility of introducing health insurance in Afghanistan: A qualitative stakeholder analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Central Statistics Organization; Ministry of Public Health (CSO & MoPH). Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-471.cfm (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Jafari, M.; Currie, S.; Qarani, W.M.; Azimi, M.D.; Manalai, P.; Zyaee, P. Challenges and facilitators to the establishment of a midwifery and nursing council in Afghanistan. Midwifery 2019, 75, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, N.P.H.; Nguyen, D.; Sediqi, S.M.; Tran, L.; Huy, N.T. Healthcare collapse in Afghanistan due to political crises, natural catastrophes, and dearth of international aid post-COVID. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afghanistan Refugee Crisis Explained. Available online: https://www.unrefugees.org/news/afghanistan-refugee-crisis-explained/ (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Mackintosh, E.C. Taliban Decree on Women’s Rights, Which Made No Mention of School or Work, Dismissed by Afghan Women and Experts; CNN: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2021/12/03/asia/afghanistan-taliban-decree-womens-rights-intl/index.html (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Kottasová, I. Taliban Suspend University Education for Women in Afghanistan; CNN: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/20/asia/taliban-bans-women-university-education-intl/index.html (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Gumede, S.; Black, V.; Naidoo, N.; Chersich, M.F. Attendance at antenatal clinics in inner-city Johannesburg, South Africa and its associations with birth outcomes: Analysis of data from birth registers at three facilities. BMC Public Health 2017, 17 (Suppl. S3), 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrevaya, J. The effects of demographics and maternal behavior on the distribution of birth outcomes. In Economic Applications of Quantile Regression; Physica: Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, G.R.; Korenbrot, C.C. The role of prenatal care in preventing low birth weight. Future Child. 1995, 5, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauserman, M.; Lokangaka, A.; Thorsten, V. Risk factors for maternal death and trends in maternal mortality in low- and middle-income countries: A prospective longitudinal cohort analysis. Reprod. Health 2015, 12 (Suppl. S2), S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basij-Rasikh, M.; Dickey, E.S.; Sharkey, A. Primary healthcare system and provider responses to the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan. BMJ Glob. Health 2024, 9, e013760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 10 Best and Worst Countries to Be a Woman in 2021. Available online: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/best-worst-countries-for-women-gender-equality/ (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Ibrahimi, S.; Thoma, M.E. The association between Afghan women’s autonomy and experience of domestic violence, moderated by education status. Prev. Med. 2024, 185, 108039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, R.; Galal, O.; Lu, M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: A contextual analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 69, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi, S.; Alamdar Yazdi, A.; Yusuf, K.K.; Salihu, H.M. Association of domestic physical violence with feto-infant outcomes in Afghanistan. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2021, 33, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, T.W. Mortality Rate, Under-5 (per 1,000 Live Births)—Afghanistan. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?locations=AF (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- UNICEF DATA. Afghanistan (AFG)—Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/country/afg/ (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Schunk, D.H. Social cognitive theory. In APA Educational Psychology Handbook, Vol 1: Theories, Constructs, and Critical Issues; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: A Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/258734 (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IndiaTimes. Taliban Terror: Afghan Women Banned from Seeing Male Doctors, Athletes Barred from Playing. Available online: https://www.indiatimes.com/trending/social-relevance/afghan-women-banned-from-seeing-male-doctors-beauty-salons-to-shut-down-590044.html (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Glass, N.; Jalalzai, R.; Spiegel, P.; Rubenstein, L. The crisis of maternal and child health in Afghanistan. Confl. Health 2023, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.P. Investments in women, economic development, and improvements in health in low-income countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1989, 569, 288–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNAMA. A Long Way to Go: Implementation of the Elimination of Violence against Women Law in Afghanistan. 2011. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/AF/UNAMA_Nov2011.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Turkmani, S.; Currie, S.; Mungia, J.; Assefi, N.; Javed Rahmanzai, A.; Azfar, P.; Bartlett, L. ‘Midwives are the backbone of our health system’: Lessons from Afghanistan to guide expansion of midwifery in challenging settings. Midwifery 2013, 29, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.K. By Banning Women from Working in NGOs in Afghanistan, the Taliban Forget That Women Are Needed to Serve Other Women. Available online: https://www.idsociety.org/science-speaks-blog/2023/by-banning-women-from-working-in-ngos-in-afghanistan-the-taliban-forget-that-women-are-needed-to-serve-other-women/ (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Safi, N.; Anwari, P.; Safi, H. Afghanistan’s health system under the Taliban: Key challenges. Lancet 2022, 400, 1179–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Brugha, R.; Hanson, K.; McPake, B. What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries? Bull. World Health Organ. 2002, 80, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Agha, S.; Gage, A.; Balal, A. Changes in perceptions of quality of, and access to, services among clients of a fractional franchise network in Nepal. J. Biosoc. Sci. 2007, 39, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, S.; Karim, A.M.; Balal, A.; Sosler, S. The impact of a reproductive health franchise on client satisfaction in rural Nepal. Health Policy Plan. 2007, 22, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feminist Majority Foundation Blog; FMF Staff. Taliban Bans the Selling of Contraceptives in Afghanistan. Feminist Majority Foundation. 2023. Available online: https://feminist.org/news/taliban-bans-the-selling-of-contraceptives-in-afghanistan/ (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Ibrahimi, S.; Steinberg, J.R. Spousal violence and contraceptive use among married Afghan women in a nationally representative sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi, S.; Youssouf, B.; Potts, C.; Dumouza, A.; Duff, R.; Malaba, L.S.; Brunner, B. United States government-supported family planning and reproductive health outreach in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: Lessons learned and recommendations. Open Access J. Contracept. 2024, 15, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzón-Duque, M.O.; Cardona-Arango, M.D.; Rodríguez-Ospina, F.L.; Segura-Cardona, A.M. Informality and employment vulnerability: Application in sellers with subsistence work. Rev. Saúde Pública 2017, 51, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chansa, C.; Mwase, T.; Matsebula, T.C.; Kandoole, P.; Revill, P.; Makumba, J.B.; Lindelow, M. Fresh money for health? The (false?) promise of “innovative financing” for health in Malawi. Health Syst. Reform 2018, 4, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahimi, S.; Yeo, S.; Korede, Y.; Akrami, Z. Factors hindering access and utilization of maternal healthcare in Afghanistan after Taliban’s control in 2021 and recommended solutions. In Proceedings of the 2023 APHA Annual Meeting and Expo, Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–15 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Providers n (%) | Patients n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range) | 35 (25–53) | ||

| Ethnicity | Tajik | 1 (20) | 3 (43) |

| Pashtun | 1 (20) | 2 (29) | |

| Hazara | 3 (60) | 2 (29) | |

| Education level | No education | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Some high school | 0 (0) | 3 (43) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 (80) | 3 (43) | |

| Medical degree | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Employment status (4+ years of work experience) | Full-time | 4 (80) | 0 (0) |

| Part-time | 1 (20) | 2 (29) | |

| Housewife | 0 (0) | 5 (71) | |

| Current place of residence | Afghanistan | 4 (60) | 7 (100) |

| Recent refugee (U.S.) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | |

| Number of children | None | 2 (40) | 0 (0) |

| Two | 2 (40) | 2 (29) | |

| Three or more | 1 (20) | 5 (71) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ibrahimi, S.; Yeo, S.; Yusuf, K.; Akrami, Z.; Roy, K. Factors Hindering Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in Afghanistan Under the Taliban Regime: A Qualitative Study with Recommended Solutions. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091006

Ibrahimi S, Yeo S, Yusuf K, Akrami Z, Roy K. Factors Hindering Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in Afghanistan Under the Taliban Regime: A Qualitative Study with Recommended Solutions. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091006

Chicago/Turabian StyleIbrahimi, Sahra, Sarah Yeo, Korede Yusuf, Zarah Akrami, and Kevin Roy. 2025. "Factors Hindering Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in Afghanistan Under the Taliban Regime: A Qualitative Study with Recommended Solutions" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091006

APA StyleIbrahimi, S., Yeo, S., Yusuf, K., Akrami, Z., & Roy, K. (2025). Factors Hindering Access and Utilization of Maternal Healthcare in Afghanistan Under the Taliban Regime: A Qualitative Study with Recommended Solutions. Healthcare, 13(9), 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091006