Smoking Pregnant Woman: Individual, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

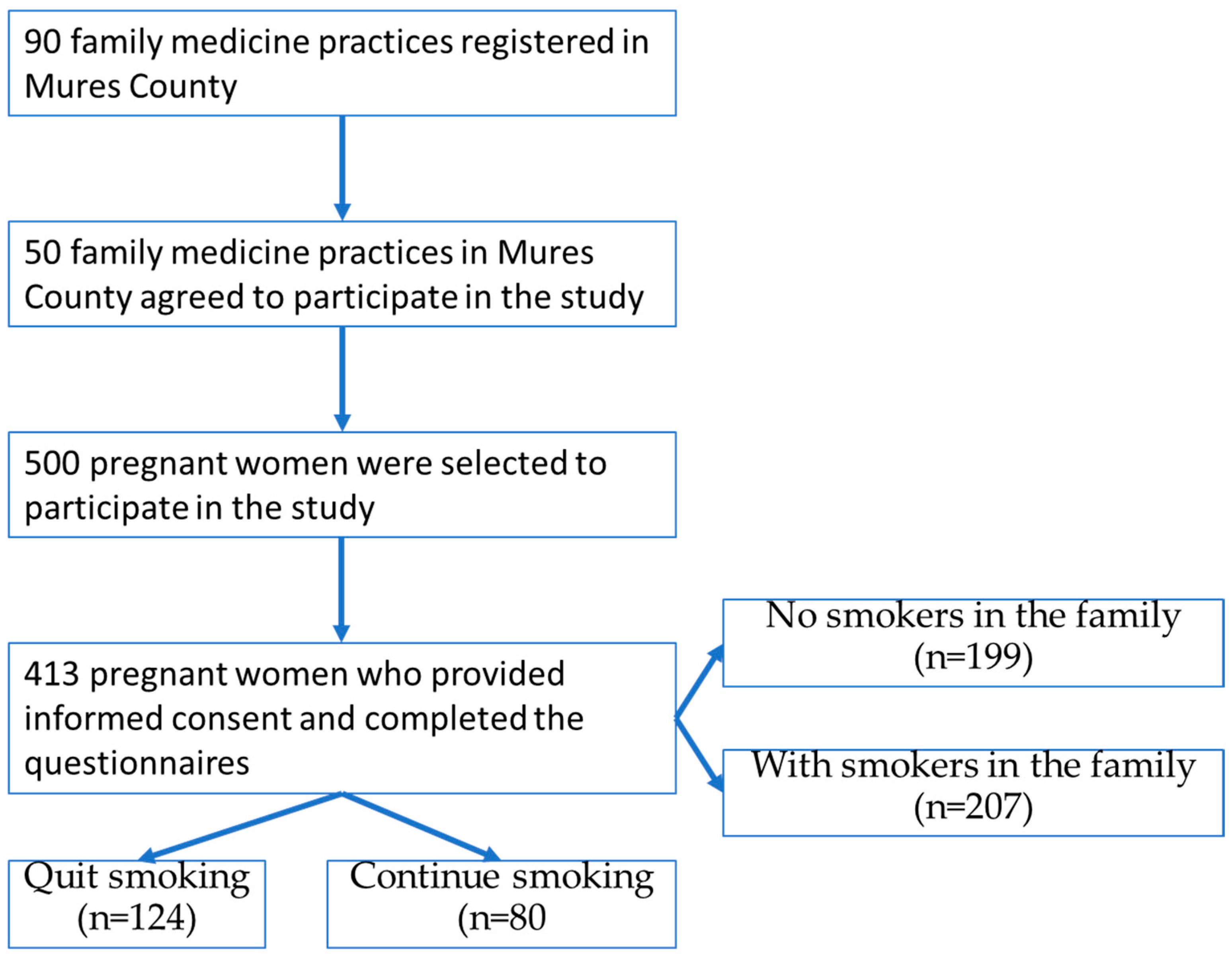

2.1. Participants

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Questions Regarding the Assessment of Tobacco Exposure

2.2.2. Questions Regarding the Assessment of Anti-Smoking Interventions Provided by GPs

2.2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Socio-Demographic, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects

3.2. Socio-Demographic, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects in Relation to Smoking Status During Pregnancy

3.3. Individual Aspects Regarding the Pregnant Woman’s Understanding of the Relationship Between Exposure to Smoking and the Risk to the Health of the Mother and Child

3.4. Multifactorial Analysis Associated with Attitudes Towards Smoking During Pregnancy and the Risk of Passive Exposure Through Smoking Family Members

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pilehvari, A.; Chipoletti, A.; Krukowski, R.; Little, M. Unveiling socioeconomic disparities in maternal smoking during pregnancy: A comprehensive analysis of rural and Appalachian areas in Virginia utilizing the multi-dimensional YOST index. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peyronnet, V.; Le Faou, A.L.; Berlin, I. Sevrage tabagique au cours de la grossesse [Smoking cessation during pregnancy]. Rev. Des Mal. Respir. 2024, 41, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S.; Probst, C.; Rehm, J.; Popova, S. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e769–e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, J.T.; Melknikow, J.; Coppola, E.L.; Durbin, S.; Thomas, R. Interventions for Tobacco Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: An Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021, 325, 280–298. [Google Scholar]

- Patnode, C.D.; Henderson, J.T.; Melknikow, J.; Coppola, E.L.; Durbin, S.; Thomas, R. Interventions for tobacco cessation in adults, including pregnant women: Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2021, 325, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Manhungira, W.; Sankar, A.; Sarkar, R. Women’s Perspectives on Smoking During Pregnancy and Factors Influencing Their Willingness to Quit Smoking in Pregnancy: A Study From the United Kingdom. Cureus 2023, 15, e38890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, R.; Silva, D.; Piumika, L.; Abeysekera, I.; Jayathilaka, R.; Rajamanthri, L.; Wickramaarachchi, C. Impact of global smoking prevalence on mortality: A study across income groups. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keten, E.E.; Keten, M. Why women continue to smoke during pregnancy: A qualitative study among smoking pregnant women. Women Health 2023, 63, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derksen, M.E.; Kunst, A.E.; Murugesu, L.; Jaspers, M.W.M.; Fransen, M.P. Smoking cessation among disadvantaged young women during and after pregnancy: Exploring the role of social networks. Midwifery 2021, 98, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, N.K.; Graham, A.L.; Byron, M.J.; Niaura, R.S.; Abrams, D.B. Online Social Networks and Smoking Cessation: A Scientific Research Agenda. J. Med. Int. Res. 2011, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.; Luckett, T.; Davidson, P.M.; Giacomo, M.D. Interventions to reduce harm from smoking with families in infancy and early childhood: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 3091–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, C.; Omara-Eves, A.; Oliver, S.; Caird, J.R.; Perlen, S.M.; Eades, S.J.; Thomas, J. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 10, CD001055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagawa, C.S.; Lane, I.A.; Davis, M.; Wang, B.; Pbert, L.; Lemon, S.C.; Sadasivam, R.S. Experiences Using Family or Peer Support for Smoking Cessation and Considerations for Support Interventions: A Qualitative Study in Persons With Mental Health Conditions. J. Dual Diagn. 2023, 19, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazer, K.; Fitzpatrick, P.; Brosnan, M.; Dromey, A.M.; Kelly, S.; Murphy, M.; O’Brien, D.; Kelleher, C.C.; McAuliffe, F.M. Smoking Prevalence and Secondhand Smoke Exposure during Pregnancy and Postpartum-Establishing Risks to Health and Human Rights before Developing a Tailored Programme for Smoking Cessation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voidazan, S.; Tarcea, M.; Abram, Z.; Georgescu, M.; Marginean, C.; Grama, O.; Buicu, F.; Ruţa, F. Associations between lifestyle factors and smoking status during pregnancy in a group of Romanian women. Birth Defects Res. 2018, 110, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruta, F.; Avram, C.; Voidăzan, S.; Mărginean, C.; Bacârea, V.; Ábrám, Z. Active Smoking and Associated Behavioural Risk Factors before and during Pregnancy—Prevalence and Attitudes among Newborns Mothers in Mures County, Romania. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 24, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naughton, F.; Hopewell, S.; Sinclair, L.; McCaughan, D.; McKell, J.; Bauld, L. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation in pregnancy and in the postpartum period: The Health Care Professionals’ perspective. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2018, 23, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeks, R.; Padmakumar, G.; Andrew, B.; Huynh, D.; Longman, J. Barriers and enablers to implementation of antenatal smoking cessation guidelines in general practice. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2020, 26, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, K.; Graham, H.; McCaughan, D.; Angus, K.; Bauld, L. The barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by women’s partners during pregnancy and the post-partum period: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenstock, J.; Sniehotta, F.F.; White, M.; Bell, R.; Milne, E.M.; Araujo-Soares, V. What helps and hinders midwives in engaging with pregnant women about stopping smoking? A cross-sectional survey of perceived implementation difficulties among midwives in the North East of England. Implement Sci. 2012, 24, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila-Farinas, A.; Pérez-Rios, M.; Montes-Martinez, A.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Forray, A.; Rey-Brandariz, J.; Candal-Pedreira, C.; Fernández, E.; Casal-Acción, B.; Varela-Lema, L. Effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions among pregnant women: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict. Behav. 2024, 148, 107854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomar, M.; Tong, V.T.; Morello, P.; Farr, S.L.; Lawsin, C.; Dietz, P.M.; Aleman, A.; Berrueta, M.; Mazzoni, A.; Becu, A.; et al. Barriers and promoters of an evidenced-based smoking cessation counseling during prenatal care in Argentina and Uruguay. Matern. Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1481–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, K.; Graham, H.; McCaughan, D.; Angus, K.; Sinclair, L.; Bauld, L. Health professionals’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators to providing smoking cessation advice to women in pregnancy and during the post-partum period: A systematic review of qualitative research. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, T.; Babayan, A.; Irfan, S.; Schwartz, R. Exploring the adequacy of smoking cessation support for pregnant and postpartum women. BMC Public Health 2013, 14, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallus, S.; Lugo, A.; Liu, X.; Behrakis, P.; Boffi, R.; Bosetti, C.; Carreras, G.; Chatenoud, L.; Clancy, L.; Continente, X.; et al. TackSHS Project Investigators. Who Smokes in Europe? Data From 12 European Countries in the TackSHS Survey (2017–2018). J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, A.; Rajabi, A.; Gholian-Aval, M.; Peyman, N.; Mahdizadeh, M.; Tehrani, H. National, regional, and global prevalence of cigarette smoking among women/females in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Willemsen, M.; Mons, U.; Fernández, E. Tobacco control in Europe: Progress and key challenges. Tob Control 2022, 31, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, F.; Gewily, S.E.; Bardoutos, A. Smoking epidemic in Europe in the 21st century. Tob. Control. 2021, 30, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, O.M.; Bacarea, A.; Ruta, F.; Bacarea, V.; Gliga, F.I.; Buicu, F. Anthropometric indices of the newborns related to some lifestyle parameters of women during pregnancy in Tirgu Mures region—A pilot study. Prog. Nutr. 2018, 20, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagadec, N.; Steinecker, M.; Kapassi, A.; Magnier, A.M.; Chastang, J.; Robert, S.; Gaouaou, N.; Ibanez, G. Factors influencing the quality of life of pregnant women: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dherani, M.; Zehra, S.N.; Jackson, C.; Satyanaryana, V.; Huque, R.; Chandra, P.; Rahman, A.; Siddiqi, K. Behaviour change interventions to reduce second-hand smoke exposure at home in pregnant women—A systematic review and intervention appraisal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allkins, S. Smoking during pregnancy: Latest data. Br. J. Midwifery 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, L.; Stevens, R.; Nicholson, B.D.; Wherton, J.; Gao, M.; Callan, C.; Haasova, S.; Aveyard, P. Strategies to improve the implementation of preventive care in primary care: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2024, 1, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipling, L.; Bombard, J.; Wang, X.; Cox, S. Cigarette Smoking Among Pregnant Women During the Perinatal Period: Prevalence and Health Care Provider Inquiries. Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2024, 73, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krist, A.H.; Davidson, K.W.; Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Cabana, M.; Caughey, A.B.; Donahue, K.; Doubeni, C.A.; Epling, J.W., Jr.; Kubik, M.; et al. Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA 2021, 325, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avşar, T.S.; McLeod, H.; Jackson, L. Health outcomes of smoking during pregnancy and the postpartum period: An umbrella review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinzaniuc, A.; Strilciuc, A.; Blaga, O.; Chereches, R.; Meghea, C. Smoking and quitting smoking during pregnancy: A qualitative exploration of the socio-cultural context for the development of a couple-based smoking cessation intervention in Romania. Tob. Prev. Cessat. 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Yaghoub, M.; Elhomani, A.; Catley, D. Effectiveness of motivational interviewing, health education and brief advice in a population of smokers who are not ready to quit. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tafti, S.P.; Azarshab, A.; Mahmoudian, R.A.; Khayami, R.R.A.; Abadi, R.N.S.; Ahmadi-Simab, S.; Shahidsales, S.; Vakilzadeh, M.M. Predictors of tobacco use among pregnant women: A large-scale, retrospective study. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, K.; Capponi, S.; Nyamukapa, M.; Baxter, J.; Crawford, A.; Worly, B. Partner Involvement During Pregnancy and Maternal Health Behaviors. Matern. Child Health J. 2016, 20, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, A.; Adrian, G.; Laura, A.E. New approach on optimal decision making based on formal automata models. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 3, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calin, A.; Laura, A.E.; Adrian, G. Formal Models for Describing Mathematical Programming Problem. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 1501–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, C.; Gligor, A.; Avram, L.A. Formal Model Based Automated Decision Making. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 46, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statement | n | % | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual aspects | |||

Residence

| |||

| 228 | 55.2 | 50.4–60 | |

| 185 | 44.8 | 40.0–49.6 | |

Marital status:

| |||

| 289 | 70.0 | 65.4–74.1 | |

| 62 | 15.0 | 11.6–18.4 | |

| 54 | 13.1 | 9.9–16.2 | |

| 8 | 1.9 | 0.7–3.4 | |

Ethnicity

| |||

| 276 | 66.8 | 62.5–71.2 | |

| 91 | 22.0 | 18.2–25.9 | |

| 45 | 10.9 | 8.0–14.0 | |

| 1 | 0.2 | 0.0–1.0 | |

| Family Aspects | |||

How many smokers are in the house where you live?

| |||

| 199 | 48.2 | 43.1–53.3 | |

| 142 | 34.4 | 29.8–39.2 | |

| 49 | 11.9 | 8.5–15.2 | |

| 16 | 3.9 | 2.2–6.0 | |

| 7 | 1.7 | 0.5–3.1 | |

How is smoking seen in the place where you live?

| |||

| 245 | 59.3 | 54.2–63.9 | |

| 96 | 23.2 | 19.4–27.4 | |

| 67 | 16.2 | 12.6–20.1 | |

| 5 | 1.2 | 0.2–2.2 | |

If there are smokers in the family, have they changed this habit since the pregnancy was highlighted?

| |||

| 101 | 24.5 | 20.3–28.3 | |

| 176 | 42.6 | 37.8–47.5 | |

| 56 | 13.6 | 10.4–16.9 | |

| 33 | 8.0 | 5.3–10.7 | |

| 47 | 11.4 | 8.5–14.3 | |

| Primary Healthcare Aspects | |||

During today’s visit, did you observe any information materials (leaflets, brochures) on nicotine consumption?

| |||

| 158 | 38.3 | 34.1–42.9 | |

| 241 | 58.4 | 53.8–62.7 | |

| 14 | 3.4 | 1.7–5.1 | |

During today’s visit, were you asked by your doctor/nurse/other nurse if you were smoking?

| |||

| 350 | 84.7 | 81.1–87.9 | |

| 58 | 14.0 | 10.7–17.7 | |

| 5 | 1.2 | 0.2–2.4 | |

During today’s visit, did you pick up any informative materials that refer to cigarette smoking during pregnancy?

| |||

| 98 | 23.7 | 19.6–27.8 | |

| 245 | 59.3 | 54.2–63.9 | |

| 70 | 16.9 | 13.6–20.6 | |

| Factors of Influence over the Abandonment Decision | Total (n = 413) | Quit Smoking (n = 124) | Continue Smoking (n = 80) | No Smokers in the Family (n = 199) | With Smokers in the Family (n = 207) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual apects | |||||

| Age (average, SD) | 28.5 (5.61) | 28.9 (4.95) | 28.3 (5.81) | 29.4 (4.94) | 27.3 (6.00) |

| Pregnancy week (mean, SD) | 25 (7.93) | 25.0 (8.27) | 26.6 (5.97) | 24.8 (8.47) | 26.6 (7.13) |

| Low study level | 110 (26.63%) | 30 (24.19%) | 35 (43.75%) | 35 (17.59%) | 74 (35.75%) |

| Roma ethnics | 45 (10.90%) | 6 (4.84%) | 19 (23.75%) | 7 (3.52%) | 38 (18.36%) |

| Rural residency | 185 (44.79%) | 45 (36.29%) | 48 (60.00%) | 67 (33.67%) | 116 (56.04%) |

| Not married | 124 (30.02%) | 35 (28.23%) | 38 (47.50%) | 31 (15.58%) | 91 (43.96%) |

| Low level of information on smoking | 72 (17.43%) | 32 (25.81%) | 36 (45.00%) | 15 (7.54%) | 57 (27.54%) |

| Indifference to passive smoking | 75 (18.16%) | 21 (16.94%) | 23 (28.75%) | 24 (12.06%) | 50 (24.15%) |

| Family aspects | |||||

| Presence of smokers in the house | 207 (50.12%) | 60 (48.39%) | 74 (92.50%) | - | - |

| Smoking in the presence of pregnant women | 33 (7.99%) | 6 (4.84%) | 16 (20.00%) | 2 (1.01%) | 31 (14.98%) |

| Primary Healthcare Aspects | |||||

| Lack of informative materials to the family doctor | 241 (58.35%) | 75 (60.48%) | 57 (71.25%) | 101 (50.75%) | 137 (66.18%) |

| Lack of informative leaflets received from the family doctor | 245 (59.32%) | 70 (56.45%) | 61 (76.25%) | 104 (52.26%) | 137 (66.18%) |

| Without informational materials such as brochures or leaflets about smoking during the visit to the GPs | 176 (42.62%) | 55 (44.35%) | 54 (67.50%) | 63 (31.66%) | 112 (54.11%) |

| Statement | Quit Smoking (n = 124) | Continue Smoking (n = 80) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Smoking can cause complications with pregnancy and childbirth labor | 4.631 (0.774) | 3.663 (1.211) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy can increase the risk of miscarriage | 4.537 (0.958) | 3.650 (1.170) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy can increase the risk of a premature birth | 4.537 (0.837) | 3.696 (1.170) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy increases the chances of having a low birth weight baby | 4.439 (1.080) | 3.625 (1.257) | <0.0001 |

| Children of smokers are more likely to have asthma or any other respiratory infection | 4.504 (0.927) | 3.638 (1.255) | <0.0001 |

| If my life partner consumes tobacco around me, it will increase the risk of pregnancy complications | 4.233 (1.151) | 3.354 (1.350) | <0.0001 |

| If my life partner or other family members smoke around me, the chances of the child’s illness increase. | 4.279 (1.093) | 3.300 (1.409) | <0.0001 |

| Statement | With Smokers in the House (207) | Without Smokers in the House (199) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Smoking can cause complications with pregnancy and childbirth labor | 4.063 (1.168) | 4.656 (0.902) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy can increase the risk of miscarriage | 3.995 (1.193) | 4.710 (0.822) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy can increase the risk of a premature birth | 4.059 (1.129) | 4.691 (0.784) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking during pregnancy increases the chances of having a low birth weight baby | 3.980 (1.217) | 4.591 (0.981) | <0.0001 |

| Children of smokers are more likely to have asthma or any other respiratory infection | 4.00 (1.150) | 4.635 (0.934) | <0.0001 |

| If my life partner consumes tobacco around me, it will increase the risk of pregnancy complications | 3.730 (1.298) | 4.460 (1.039) | <0.0001 |

| If my life partner or other family members smoke around me, the chances of the child’s illness increase. | 3.727 (1.311) | 4.536 (0.981) | <0.0001 |

| Variable | Quit Smoking (n = 124) vs. Continua (n = 80) | Non-Smokers (n = 199) vs. Smokers (n = 207) in the House | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | |

| Individual apects | ||||||

| Low study level | 0.66 | 0.21–2.08 | 0.480 | 1.32 | 0.56–3.11 | 0.522 |

| Roma ethnics | 2.01 | 0.39–10.34 | 0.399 | 0.96 | 0.28–3.23 | 0.956 |

| Rural residency | 0.88 | 0.32–2.43 | 0.812 | 0.97 | 0.48–1.92 | 0.931 |

| Not married | 0.70 | 0.29–1.69 | 0.434 | 2.19 | 1.11–4.31 | 0.023 * |

| Low level of knowledge on smoking | 12.61 | 3.79–41.89 | <0.001 * | 3.64 | 1.47–9.02 | 0.005 * |

| Indifference to passive smoking | 0.49 | 0.17–1.39 | 0.183 | 1.28 | 0.56–2.92 | 0.547 |

| Family aspects | ||||||

| The presence of smokers in the house | 8.83 | 2.89–26.91 | <0.001 * | |||

| Smoking in the presence of pregnant women | 2.86 | 0.79–10.31 | 0.806 | 4.60 | 0.96–22.05 | 0.056 * |

| Lack of informative materials to the family doctor | 0.23 | 0.06–0.83 | 0.025 * | 1.10 | 0.50–2.40 | 0.804 |

| Lack of informative leaflets received from the family doctor | 5.68 | 1.45–22.19 | 0.012 * | 1.31 | 0.56–3.01 | 0.524 |

| Without informational materials such as brochures or leaflets about smoking during the visit to the GPs | 1.96 | 0.76–5.05 | 0.161 | 2.23 | 1.13–4.43 | 0.020 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruta, F.; Georgescu, I.M.; Moldovan, G.; Avram, L.; Onisor, D.; Abram, Z. Smoking Pregnant Woman: Individual, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091005

Ruta F, Georgescu IM, Moldovan G, Avram L, Onisor D, Abram Z. Smoking Pregnant Woman: Individual, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects. Healthcare. 2025; 13(9):1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091005

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuta, Florina, Ion Mihai Georgescu, Geanina Moldovan, Laura Avram, Danusia Onisor, and Zoltan Abram. 2025. "Smoking Pregnant Woman: Individual, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects" Healthcare 13, no. 9: 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091005

APA StyleRuta, F., Georgescu, I. M., Moldovan, G., Avram, L., Onisor, D., & Abram, Z. (2025). Smoking Pregnant Woman: Individual, Family, and Primary Healthcare Aspects. Healthcare, 13(9), 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13091005