“It’s More than Just Exercise”: Psychosocial Experiences of Women in the Conscious 9 Months Specifically Designed Prenatal Exercise Programme—A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Intervention: The “Conscious 9 Months” Exercise Programme

2.3. Study Participants

2.4. Data Collection

In-Depth Interviews

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Data Organisation and Management

2.5.2. Reliability Checks

2.5.3. Data Saturation

2.6. Trustworthiness

3. Results

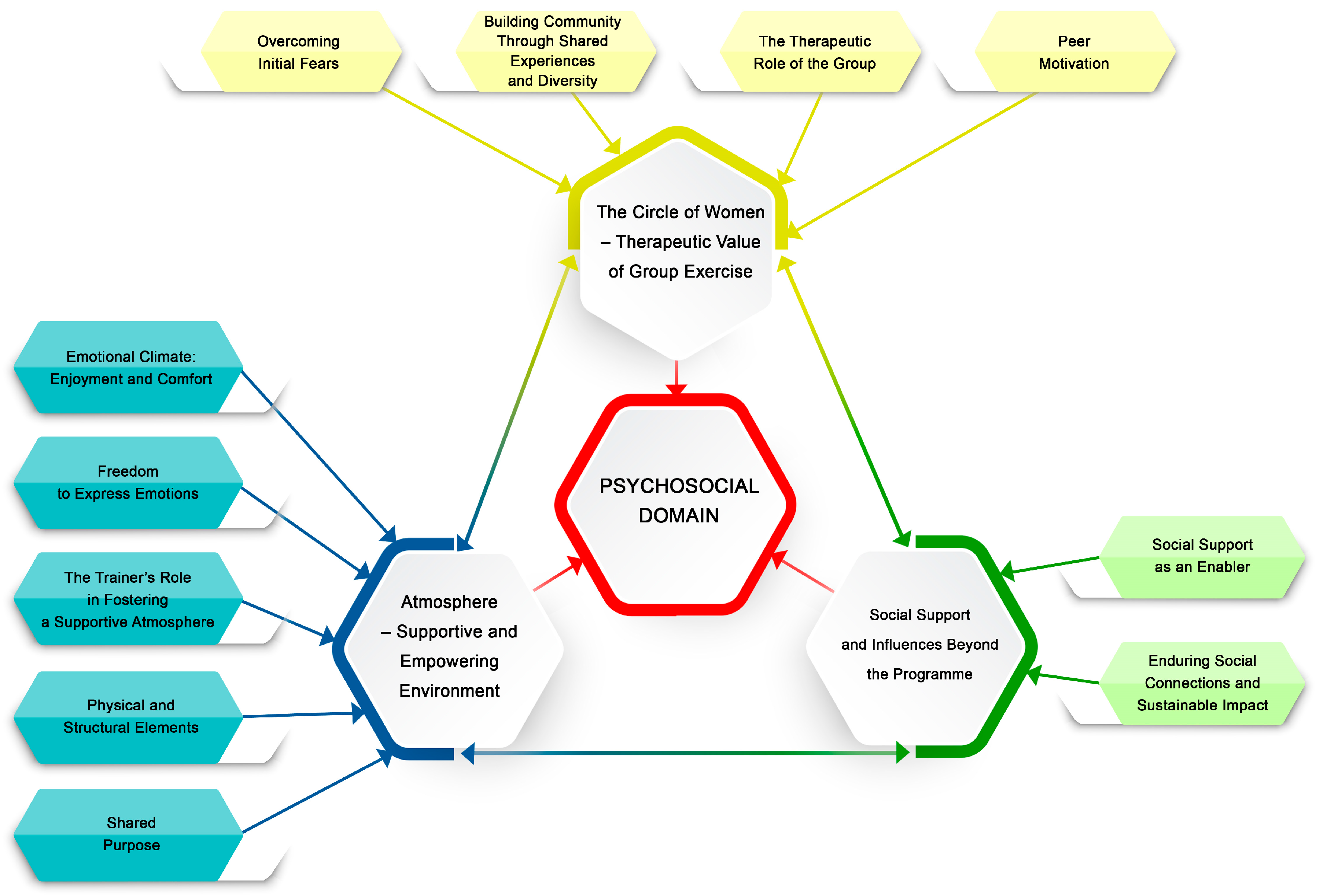

- Psychosocial domain—Small group sessions, consisting of women at different pregnancy stages, fostered a supportive community, reducing feelings of isolation and enhancing a sense of empowerment among participants. The shared pregnancy experience and the therapeutic value of group exercise enhanced motivation and encouraged adherence. The programme was characterised by a warm, supportive atmosphere, where emotions could be freely expressed.

- Physical domain—The programme featured structured yet flexible training sessions tailored to the individual needs of each pregnant woman. The trainer played a crucial role in providing personalised support, adapting exercises to participants’ physical capabilities, and fostering a sense of support and connection.

- Psychoeducational domain—The sessions reduced anxiety surrounding childbirth and equipped participants with knowledge about bodily changes, breathing techniques, birth, and the postpartum period. Education was seamlessly integrated into the movement, ensuring that women not only engaged in physical activity but also actively prepared for labour and motherhood.

- The Circle of Women: The Therapeutic Value of Group Exercise highlights the role of shared experiences in overcoming initial fears and self-doubt through being part of a community. The group setting provided emotional support and knowledge exchange, fostering confidence and reducing anxiety. It served as a therapeutic space for discussing emotions and pregnancy experiences, while also encouraging a sense of personal strength and motivation, enhancing adherence to regular exercise.

- Atmosphere: Supportive and Empowering Environment: emphasises the importance of creating an enjoyable space beyond physical activity. The atmosphere encouraged emotional openness, relaxation, comfort, and social connection, built on the shared experience of pregnancy and childbirth. Laughter and free expression contributed to a positive experience, while an empathetic and supportive trainer played a key role in maintaining trust and engagement. The atmosphere was also enhanced through the use of appropriate music and props.

- Social support and influences beyond the programme: this sub-theme explores the impact of external relationships on adherence to regular exercise. Family and partner support encouraged consistent participation, while friendships formed during the programme often extended beyond its duration, positively influencing long-term movement habits and overall well-being.

3.1. “It’s More than Just Exercise”

3.1.1. Programme as a Transformative Experience

“In other places [like antenatal educational classes], information is limited, presented in a dry way, and there’s no exercising. But here, everything was included: exercises, breathing, meeting other pregnant women, and a wonderful atmosphere—you didn’t even feel like we were meeting for a fitness class. It felt more like meeting up with friends to laugh, talk, and, additionally, exercise.”(Participant 5)

“The programme was more than just exercise; it created a support system. It gave me friendships that continue to this day and shaped the way I approach my health and well-being.”(Participant 10)

“Participating in the programme was a truly life-enriching experience—very supportive and also strengthening my physical well-being.”(Participant 4)

“Pregnancy was a time of personal growth for me, when (…) I also went to a psychologist for the first time and started learning about my emotions, becoming aware of them. I wasn’t connected to my emotions at all before, and I also touched on this in the programme.”(Participant 9)

3.1.2. The Circle of Women—Therapeutic Value of Group Exercise

- Overcoming Initial Fears

“I was afraid whether I’d manage, whether I could do it (…) for example (…) with coordination, you know, during pregnancy—like everyone else going right, and me going left. I also wondered how I’d be perceived, thoughts about myself, like whether I was good enough, or if I’d come across as clumsy or helpless.”(Participant 10)

“I had some concerns about my fitness levels because before pregnancy, I didn’t lead a particularly active lifestyle and wasn’t the sporty type. I wondered whether I would be able to keep up with the other women.”(Participant 3)

“The beginning was difficult, to be honest—difficult in the sense that I had to catch up with my physical fitness and complete all the exercises. However, by the end of my pregnancy, I felt that I was actually in better shape than when I started.”(Participant 5)

- Building Community Through Shared Experiences and Diversity

“I had the opportunity to participate with other women in the same [life] period as me, with the same problems (…) In fact, we exercised, yes, it was in a sense a physical activity, but above all it was very strengthening for me personally.”(Participant 8)

“We also knew what might await us in the next stage [of pregnancy], because we were, as far as the group was concerned, each of us was at a different stage of pregnancy.”(Participant 4)

“So well, yes, more of a mental side [was important to me] in a group, because we didn’t compete with each other (…) we were well matched.”(Participant 4)

“[With the trainer] it was a very good, nice collaboration, a nice relationship, without any of that ‘I’m the trainer, and you’re just here to exercise’ kind of attitude. It was a normal, friendly, peer-like relationship, I would say.”(Participant 1)

- The Therapeutic Role of the Group

“It was also a kind of, you could say, therapy, because it’s also that kind of support, a circle of other women who are pregnant. And also the realisation that ‘Oh, I’m not (…) alone in this. There’s one, another, and another who are going through the same thing’.”(Participant 10)

“It was a circle of women—supporting each other, learning from each other”(Participant 1)

“We were sort of like psychologists, us for each other, each of us exchanging our experiences (…)”(Participant 4)

- Peer Motivation

“It was my internal need [to be physically active].”(Participant 8)

“I just do it on my own because I know from my own experience that physical activity really has a positive effect on overall well-being.”(Participant 4)

“I decided to participate partly because my husband encouraged me, saying, ’You have to do something during these 9 months’.”(Participant 4)

“At the time, my husband said, ‘Go, go, go, go, go.’ Basically, he was pushing me to go, not in a way of motivating me by saying it would be better for me, but more like, ‘If you want to go, then go, so later you don’t say it’s my fault you didn’t go’”(Participant 2)

“It was actually my friend who also told me, ‘Go, I assure you it will make things easier’. She was really convincing me to give birth naturally and kept saying, ‘You absolutely have to go to participate in this programme’.”(Participant 2)

“It was important to me that these were group classes. I never liked the gym as just strength training exercises.”(Participant 4)

“Well, like I said, I wouldn’t go to the gym alone because I don’t have enough knowledge about exercises, and I would be afraid that I might harm myself—or even more so, that I could harm my baby.”(Participant 6)

“[The classes were a] friendly place, the opposite of the gym. I’ve never liked the gym or strength training on its own. I preferred group activities, especially in women’s clubs—that’s where I felt best.”(Participant 4)

“During the classes, I drew motivation from the other women exercising.”(Participant 2)

“I would leave those classes so energised. Not only because of the endorphins after exercising, but also because of the other women there, all with their bumps just like mine. They were working just as hard, always with a smile on their faces. That was amazing; it was very important and motivating for me.”(Participant 8)

“First of all, definitely the group—that being in a group gave motivation. When one person went, we all went again, even if sometimes you didn’t feel like it, like when you were tired. Toward the end, I didn’t always feel like going, but I thought, ‘No, I’m going’ because it’s something to get out for. And once I went and exercised, everything felt completely different afterward.”(Participant 1)

“Sometimes I wanted to just lie down, but I felt that I had to go, like the others do, so I went.”(Participant 7)

“Our group—there weren’t many of us; we had quite an intimate group, and that was nice too. Yes. There were maybe 6 or 5 of us, I don’t remember exactly, but it wasn’t a big group. It was different from being in a large group with many women; it was smaller, and that meant there was time for us and more contact with the trainer.”(Participant 10)

“The fact that our group was small made a difference—it was a nice, cosy group. (…) It wouldn’t be the same if the group were too large, with too many women. A smaller group means you’re not anonymous, and the trainer is in close contact with us.”(Participant 7)

“Yes, when a few women come to the sessions, and they’re going through similar experiences, it just makes it more cheerful and interesting.”(Participant 1)

3.1.3. Atmosphere: Supportive and Empowering Environment

- Emotional Climate: Enjoyment and Comfort

“[The most important thing was] the atmosphere, mainly the atmosphere, because I would get up and go, I just liked it. And then, over time, as my belly grew, I could see that I felt good, and those were the two main driving forces for me: the atmosphere and the fact that I felt really good after those classes.”(Participant 4)

“I just wanted to come to those classes. Sometimes, of course, you’d rather stay at home, maybe skip it—’I’m not going…’ because the classes were only two or three times a week. So sometimes I’d think, ‘No, I won’t go tomorrow…’ but then I’d feel like—‘Today, I have to’.”(Participant 8)

“Very very pleasant(…) it was that kind of setting, other women—always smiling. The trainer—also always so positive. We jumped around, jumped around—figuratively speaking, of course. But overall, very, very positive.”(Participant 8)

“The pleasant atmosphere was important. It was motivating, and you could say also informative, because the meetings weren’t just about exercising but also about sharing stories and giving each other advice.”(Participant 2)

- Freedom to Express Emotions

“It was cheerful. It wasn’t like, you know, you weren’t allowed to smile. It was genuinely, you could say, all in a pleasant atmosphere.”(Participant 2)

“There were jokes in between. Nice, really nice… nice, nice, really nice.”(Participant 7)

“There were laughs, and good times—it was more than just exercise.”(Participant 1)

- The Trainer’s Role in Fostering a Supportive Atmosphere

“And she [the trainer] would say, ‘Now we’re doing this, now we’re doing that,’ and somehow everything was very, very positive. I think Beata was the most positive figure for me; thanks to her, I didn’t get discouraged after the first or second session, thinking I couldn’t manage. Instead, I always came back with a smile and positive energy because of her.”(Participant 6)

“I think the atmosphere during these classes was all about shared motivation, collective experience, and preparing for this period. That was probably the most important thing, and it would have been missing if our trainer hadn’t been so contagious with her positive energy. I believe that, over time, the exercises alone would have become boring without it.”(Participant 5)

“She would calm us down, explain everything, and that’s what made us feel safe.”(Participant 7)

“It was also largely thanks to Beata because she knew how to bring everyone together. Of course, she’s a professional and focuses on what she does, but at the same time, she was a source of support for us.”(Participant 4)

- Physical and Structural Elements

“The music always ‘disarmed’ us, it energised us to start the workout with a smile on our faces.”(Participant 7)

“Beata would also play us relaxing music (…) It gave us a moment to just be with ourselves and also with our little ones. It was like the finishing touch to the sessions. By then, we were a bit tired from the exercises—it wasn’t always easy—but when you lay there on the mat or the floor, listening to the music, and she’d say, ‘Place your hands on your belly,’ it was such a lovely experience.”(Participant 10)

“Every exercise session was truly different. Each meeting, even though Beata had her planned repertoire of exercises, was never repetitive. The exercises were varied. We had sessions with exercise balls, sessions at the barre—some of them looked like ballet exercises. We had fun warm-ups inspired by aerobics, exercises with dumbbells and resistance bands, and general conditioning workouts, working the whole body from head to toe.”(Participant 3)

“The exercises were very engaging, and various equipment was used, such as balls, resistance bands, and bars, which prevented monotony.”(Participant 9)

“The sessions were diverse, never repeating, and included both large and small equipment.”(Participant 3)

- Shared Purpose

“I think it was the atmosphere during those classes—the shared motivation, the shared experience, preparing for this period and birth—that was the most important.”(Participant 8)

“It strengthened me to see that, you know, everyone had similar problems to some extent, but they always left with a smile and managed to handle everything, especially childbirth.”(Participant 6)

“[The atmosphere] was very positive because it was women who also, you know, sometimes had back pain, or their own pregnancy-related discomforts. But we were going through it together, experiencing it together, preparing for birth together (…) we supported each other(…). It was very, very pleasant.”(Participant 10)

3.1.4. Social Support and Influences Beyond the Programme

- Social Support as an Enabler

“The support of my partner and family was crucial, for example, knowing that I could sometimes leave my daughter with her grandmother. Family support was a significant factor that made it possible for me to take part in this experience.”(Participant 8)

“My family was very happy with what I was doing and supported me fully. They did everything they could so that I could attend the sessions, right up until the birth—every week or twice a week, depending on how the sessions were scheduled.”(Participant 7)

- Enduring Social Connections and Sustainable Impact

“I’m still in touch with the girls; I made friendships that I still maintain, and our kids still play together.”(Participant 6)

“I also opened up a bit; those classes with other women, new acquaintances, new friends, then some later get-togethers… Yes, it was all very, very positive and uplifting.”(Participant 8)

“During the programme, I became friends with another mum who had a daughter born a little earlier, and it turned out that our girls later ended up in the same preschool group. So, in a way, we also shared this experience—first, we exercised together, and now our daughters are ‘exercising’ together too.”(Participant 9)

“Before pregnancy, I wasn’t as aware and active as I became afterward. Now I know how important physical activity is not only for me but also for my child. After these classes, I started to think differently about movement and how it affects both the body and the mind.”(Participant 7)

“I was always physically active to some extent, but not at this level. Now, having children, I understand that I need to set an example and show them that movement and good nutrition are essential. This program helped me integrate this awareness into my everyday life.”(Participant 6)

“It was very important to develop body awareness, not just during movement but also in relaxation—to be able to calm down and unwind. And looking back now, I believe that body awareness is key. Since my participation in the programme, I keep deepening it to this day.”(Participant 9)

“There was a great atmosphere. The women would come, we’d laugh together, and it was such a warm environment. Yes, I miss that.”(Participant 5)

“Those were amazing classes back then. I felt great, and during my second pregnancy, I couldn’t participate in any classes, and I missed it so much. In my second pregnancy, I had to stay in bed until the end of the third month, and afterward, I had to be very cautious, and I really missed it.”(Participant 10)

“I wish those classes were available all the time because, for example, during my second pregnancy, they weren’t, and it just wasn’t the same.”(Participant 3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Holistic Approaches in Prenatal Care

4.2. Psychosocial Dimensions of the Programme

4.2.1. Group Versus Individual Approach

4.2.2. Group Exercise and Group Therapy

4.2.3. Enhancing Motivation: Key Differences Between Active and Inactive Women During Pregnancy

4.2.4. Enhanced Adherence Through Group-Based Exercise

4.3. The Role of the Atmosphere

4.4. Extending Beyond the Programme: Social Support

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Implications for Practice

- Building a Supportive Social Environment

- Small Group Size: The study highlights that an optimal group size of 6–8 participants fosters a sense of safety, enabling individualised attention from the instructor while facilitating peer support.

- Prenatal Classes as a Safe Therapeutic Space: Group sessions should foster a supportive environment in which participants feel comfortable sharing their concerns and experiences. This can be achieved by ensuring that the qualities of universality, group cohesiveness, and altruism are present. Creating opportunities for emotional expression, social support, and emotional connection is of utmost importance. This is enhanced when the group consists of pregnant women at different stages of pregnancy and with different life experiences.

- Utilising Group Motivation: Women are more likely to remain engaged in a structured group setting. Ideally, the group should include both women who were physically active before pregnancy and those who were not, as peer influence is a strong motivating factor.

- Creating a Supportive Atmosphere

- Comfortable and Intimate Environment: The training space should be quiet, private, and free from distractions to foster concentration and relaxation. Large gym settings may feel impersonal and discourage participation.

- Encouraging Emotional Expression: It is essential to foster a positive and emotionally supportive atmosphere. Opportunities for laughter, informal interactions, and open emotional expression should be actively encouraged as they contribute to a sense of community and enjoyment. Both group dynamics and the instructor play crucial roles in shaping this atmosphere, ensuring that participants feel comfortable and supported. Prioritising these elements in prenatal exercise classes can significantly influence women’s willingness to engage in and sustain physical activity throughout pregnancy. A knowledgeable, empathetic, and supportive instructor plays a crucial role in creating an appropriate atmosphere.

- Essential Equipment: The programme should provide mats, exercise balls, rollers, blankets, cushions, and resistance bands to ensure comfort and versatility in movement.

- Appropriate Music Selection: Music should align with different phases of the session, ranging from more dynamic beats for the warm-up, moderate tempo during strength exercises, and calming sounds during relaxation.

- Supporting Long-Term Health and Well-Being

- Encouraging Partner and Family Involvement: Programmes should integrate strategies that actively involve partners and family members (e.g., prenatal workshops or information sessions) to reinforce long-term engagement.

- Sustained Social Connections Beyond the Programme: The study found that women continued their friendships after the programme ended, emphasising the importance of follow-up initiatives such as alumni groups, online forums, or informal meet-ups.

- Sustaining Engagement Beyond Pregnancy: Ensuring continuity of support through postnatal movement programmes, mother-baby exercise sessions, and postpartum recovery groups can promote long-term adherence to movement practices.

- Expanding access to specifically designed holistic prenatal exercise programmes is crucial, as many women report a lack of suitable opportunities that integrate physical activity with social and emotional support. Developing and promoting such programmes can help ensure that more pregnant women have access to structured, supportive environments that encourage regular participation and overall well-being.

4.7. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, I.; Hartkopf, J.; Kullmann, S.; Schleger, F.; Hallschmid, M.; Pauluschke-Fröhlich, J.; Fritsche, A.; Preissl, H. Spotlight on the fetus: How physical activity during pregnancy influences fetal health: A narrative review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2020, 6, e000658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mudd, L.M.; Owe, K.M.; Mottola, M.F.; Pivarnik, J.M. Health benefits of physical activity during pregnancy: An international perspective. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2013, 45, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brodowska, E.; Bąk-Sosnowska, M. The impact of pregnancy on women’s health and mental well-being. In Human Health in Ontogeny. Biomedical and Psychosocial Aspects; Knapik, A., Beňo, P., Rottermund, J., Eds.; Studies by Polish, Slovak and Czech researchers. T.II. Psychosocial aspects; Śląski Universytet Medyczny: Katowice, Poland, 2021; pp. 15–21. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Burrueco, J.R.; Cano-Ibáñez, N.; Martín-Peláez, S.; Khan, K.S.; Amezcua-Prieto, C. Effects on the maternal-fetal health outcomes of various physical activity types in healthy pregnant women. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 262, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, L.E.; Allen, J.J.; Gustafson, K.M. Fetal and maternal cardiac responses to physical activity and exercise during pregnancy. Early Hum. Dev. 2016, 94, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinhouya, B.C.; Duclos, M.; Enea, C.; Storme, L. Beneficial effects of maternal physical activity during pregnancy on fetal, newborn, and child health: Guidelines for interventions during the perinatal period from the French National College of Midwives. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaruk, B.; Iciek, R.; Zalewski, A.; Galczak-Kondraciuk, A.; Grantham, W. The effects of a physical exercise program on fetal well-being and intrauterine safety. Ginekol. Pol. 2021, 92, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Gou, W.H.; Wang, J.; Chen, D.D.; Sun, W.J.; Guo, P.P.; Zhang, X.-H.; Zhang, W. Effects of exercise on pregnant women’s quality of life: A systematic review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2019, 242, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mascio, D.; Magro-Malosso, E.R.; Saccone, G.; Marhefka, G.D.; Berghella, V. Exercise during pregnancy in normal-weight women and risk of preterm birth: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 804. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e178–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales, M.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Barakat, R.; Cordero, Y.; Peláez, M.; López, C.; Ruilope, L.M.; Santos-Lozano, A.; Lucia, A. Gestational exercise and maternal and child health: Effects until delivery and at post-natal follow-up. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rafie, M.M.; Khafagy, G.M.; Gamal, M.G. Effect of aerobic exercise during pregnancy on antenatal depression. Int. J. Women’s Health 2016, 8, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolong, K.; Jenkins, S.; Clark, M.M.; Borowski, K.; Nelson, N.; Moore, K.M.; Bobo, W.V. The association of exercise during pregnancy with trimester-specific and postpartum quality of life and depressive symptoms in a cohort of healthy pregnant women. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2018, 21, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchat, S.M.; Mottola, M.F.; Skow, R.J.; Nagpal, T.S.; Meah, V.L.; James, M.; Riske, L.; Sobierajski, F.; Kathol, A.J.; Marchand, A.-A.; et al. Effectiveness of exercise interventions in the prevention of excessive gestational weight gain and postpartum weight retention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeish, J.; Redshaw, M. A qualitative study of the experiences of women who are obese and pregnant in the UK. Midwifery 2011, 27, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridis, I.; Bakaloudi, D.R.; Oikonomidou, A.C.; Dagklis, T.; Chourdakis, M. Exercise during pregnancy: A comparative review of guidelines. J. Perinat. Med. 2020, 48, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottola, M.F.; Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.-M.; Davies, G.A.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Jaramillo Garcia, A.; Barrowman, N.; Adamo, K.B.; Duggan, M.; et al. 2019 Canadian guideline for physical activity throughout pregnancy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatkowska, E.; Kajdy, A.; Sikora-Szubert, A.; Karowicz-Bilinska, A.; Zembron-Lacny, A.; Ciechanowski, K.; Krzywanski, J.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Kostka, T.; Sieroszewski, P.; et al. Polish Society of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (PTGiP) and Polish Society of Sports Medicine (PTMS) recommendations on physical activity during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Ginekol. Pol. 2024, 95, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, A.; Jainta, N.; Hauzer, A.; Fuchs, P.; Czech, I.; Sikora, J.; Drosdzol-Cop, A.; Zborowska, K.; Skrzypulec-Plinta, V. Physical activity in pregnancy—A review of literature and current recommendations. Ginekol Położ Med Proj. 2018, 2, 17–21. Available online: https://www.ginekologiaipoloznictwo.com/articles/physical-activity-in-pregnancy--a-review-of-literature-and-current-recommendations.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Hayman, M.; Brown, W.J.; Brinson, A.; Budzynski-Seymour, E.; Bruce, T.; Evenson, K.R. Public health guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy from around the world: A scoping review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Barakat, R.; Brown, W.J.; Dargent-Molina, P.; Haruna, M.; Mikkelsen, E.M.; Mottola, M.F.; Owe, K.M.; Rousham, E.K.; Yeo, S. Guidelines for physical activity during pregnancy: Comparisons from around the world. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2014, 8, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, Q.; Han, R.; Xiang, Z.; Gao, L. Clinical practice guidelines that address physical activity and exercise during pregnancy: A systematic review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gascoigne, E.L.; Webster, C.M.; Honart, A.W.; Wang, P.; Smith-Ryan, A.; Manuck, T.A. Physical activity and pregnancy outcomes: An expert review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2023, 5, 100758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Rocha, R.; Fernandes de Carvalho, M.; Prior de Freitas, J.; Wegrzyk, J.; Szumilewicz, A. Active pregnancy: A physical exercise program promoting fitness and health during pregnancy—Development and validation of a complex intervention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, R.; Antunes, R.; Mendes, D.; Szumilewicz, A.; Santos-Rocha, R. Can Group Exercise Programs Improve Health Outcomes in Pregnant Women? An Updated Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, S.L.; Surita, F.G.; Godoy, A.C.; Kasawara, K.T.; Morais, S.S. Physical activity patterns and factors related to exercise during pregnancy: A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegaard, H.K.; Kjaergaard, H.; Damm, P.P.; Petersson, K.; Dykes, A.-K. Experiences of Physical Activity during Pregnancy in Danish Nulliparous Women with a Physically Active Lifestyle before Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, A.L.; Taylor, N.F.; Shields, N.; Frawley, H.C. Attitudes, barriers and enablers to physical activity in pregnant women: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2018, 64, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeough, R.; Blanchard, C.; Piccinini-Vallis, H. Pregnant and postpartum women’s perceptions of barriers to and enablers of physical activity during pregnancy: A qualitative systematic review. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2022, 67, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, S.; Sinclair, M.; Murphy, M.H.; Madden, E.; Dunwoody, L.; Liddle, D. Reducing the decline in physical activity during pregnancy: A systematic review of behaviour change interventions. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardsen, K.R.; Falk, R.S.; Jenum, A.K.; Mørkrid, K.; Martinsen, E.W.; Ommundsen, Y.; Berntsen, S. Predicting who fails to meet the physical activity guideline in pregnancy: A prospective study of objectively recorded physical activity in a population-based multi-ethnic cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016, 16, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central][Green Version]

- Gaston, A.; Cramp, A. Exercise during pregnancy: A review of patterns and determinants. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2013, 14, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szamotulska, K.; Mierzejewska, E. Physical activity during pregnancy in Poland: Current state and barriers. Ginekol. Pol. 2023, 94, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.; Cisewski, J.; Lock, E.F.; Marron, J.S. Exploratory analysis of exercise adherence patterns with sedentary pregnant women. Nurs. Res. 2010, 59, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borodulin, K.; Evenson, K.R.; Wen, F.; Herring, A.H.; Benson, A.M. Physical activity patterns during pregnancy. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, M.A.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Kleinman, K.P.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Peterson, K.E.; Gillman, M.W. Predictors of change in physical activity during and after pregnancy: Project Viva. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 32, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, S.L.; Surita, F.G.; Cecatti, J.G. Physical exercise during pregnancy: A systematic review. Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 24, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mutawtah, M.; Campbell, E.; Kubis, H.-P.; Erjavec, M. Women’s Experiences of Social Support during Pregnancy: A Qualitative Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, D.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Paxton, S.J.; Kelly, L. Factors related to exercise over the course of pregnancy including women’s beliefs about the safety of exercise during pregnancy. Midwifery 2009, 25, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramp, A.G.; Bray, S.R. A prospective examination of exercise and barrier self-efficacy to engage in leisure-time physical activity during pregnancy. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C.V.; Domingues, M.R.; Gonçalves, H.; Bertoldi, A.D. Perceived barriers to leisure-time physical activity during pregnancy: A literature review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; He, J.; Szumilewicz, A. Pregnancy activity levels and impediments in the era of COVID-19 based on the health belief model: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kianfard, L.; Niknami, S.; SHokravi, F.A.; Rakhshanderou, S. Facilitators, barriers, and structural determinants of physical activity in nulliparous pregnant women: A qualitative study. J. Pregnancy 2022, 2022, 5543684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flannery, C.; McHugh, S.; Anaba, A.E.; Clifford, E.; O’Riordan, M.; Kenny, L.C.; McAuliffe, F.M.; Kearney, P.M.; Byrne, M. Enablers and Barriers to Physical Activity in Overweight and Obese Pregnant Women: An Analysis Informed by the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B Model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2018, 18, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov Fieril, K.; Fagevik Olsén, M.; Glantz, A.; Larsson, M. Experiences of exercise during pregnancy among women who perform regular resistance training: A qualitative study. Phys. Ther. 2014, 94, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Terrones, M.; Barakat, R.; Santacruz, B.; Fernandez-Buhigas, I.; Mottola, M.F. Physical exercise programme during pregnancy decreases perinatal depression risk: A randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, E.; Straker, L.; Hamer, M.; Gebel, K. The 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: What’s new? Implications for clinicians and the public. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worska, A.; Laudańska-Krzemińska, I.; Ciążyńska, J.; Jóźwiak, B.; Maciaszek, J. New public health and sport medicine institutions guidelines of physical activity intensity for pregnancy- a scoping review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, L.; Bould, K.; Aspin-Wood, B.; Sinclair, L.; Ikramullah, Z.; Abayomi, J. The Lived Experiences of Women Exploring a Healthy Lifestyle, Gestational Weight Gain and Physical Activity throughout Pregnancy. Health Expect. 2022, 25, 1717–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, R.; Larkin, M.; Olander, E.K.; Atkinson, L. In search of the ‘like-minded’ people: Pregnant women’s sense-making of their physical activity-related social experiences. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findley, A.; Smith, D.M.; Hesketh, K.; Keyworth, C. Exploring women’s experiences and decision making about physical activity during pregnancy and following birth: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020, 20, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilar Budler, L.; Budler, M. Physical activity during pregnancy: A systematic review for the assessment of current evidence with future recommendations. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grenier, L.N.; Atkinson, S.A.; Mottola, M.F.; Wahoush, O.; Thabane, L.; Xie, F.; Vickers-Manzin, J.; Moore, C.; Hutton, E.K.; Murray-Davis, B. Be healthy in pregnancy: Exploring factors that impact pregnant women’s nutrition and exercise behaviours. Matern. Child Nutr. 2021, 17, e13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makaruk, B.; Grantham, W.; Organista, N.; Płaszewski, M. “Conscious Nine Months”: Exploring Regular Physical Activity amongst Pregnant Women—A Qualitative Study Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 160940691989922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkes, A.C.; Smith, B. Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: Criteriology and relativism in action. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2009, 10, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G.; Lincoln, Y.S. Fourth Generation Evaluation; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.; Caddick, N. Qualitative methods in sport: A concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia Pac. J. Sport Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, H. Holistic Education to Empower and Enhance Women’s Health Throughout Pregnancy, Birth, and the Postpartum Period. Capstone Projects. Ph.D. Thesis, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haakstad, L.A.H.; Voldner, N.; Henriksen, T.; Bø, K. Physical activity level and weight gain in a cohort of pregnant Norwegian women. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2007, 86, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ickovics, J.R.; Reed, E.; Magriples, U.; Westdahl, C.; Schindler Rising, S.; Kershaw, T.S. Effects of group prenatal care on psychosocial risk in pregnancy: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 110, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, N.; Lydell, M.; Carlsson, I.M. “Womanhood,” a shared experience of participating in a lifestyle intervention with a focus on integration and physical activity to promote health among pregnant women: Perspectives from pregnant women, midwives, and cultural interpreter doulas. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, A.; Prapavessis, H. Maternal-Fetal Disease Information as a Source of Exercise Motivation during Pregnancy. Health Psychol. 2009, 28, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Ninh, L.T.; Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, A.D.; Vu, L.G.; Nguyen, H.S.A.; Nguyen, S.H.; Doan, L.P.; Vu, T.M.T.; et al. Women’s holistic self-care behaviors during pregnancy and associations with psychological well-being: Implications for maternal care facilities. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.M.; Carron, A.V.; Eys, M.A.; Ntoumanis, N.; Estabrooks, P.A. Group versus individual approach? A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of interventions to promote physical activity. Sport Exerc. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 2, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Dishman, R.K.; Buckworth, J. Increasing physical activity: A quantitative synthesis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1996, 28, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, E.J.M.; Benton, M.; Gardner, R.; Tribe, R. Balancing benefits and risks of exercise in pregnancy: A qualitative analysis of social media discussion. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2024, 10, e002176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalom, I.D.; Leszcz, M. The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy; Basic books: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hovland, A.; Nordhus, I.H.; Sjøbø, T.; Gjestad, B.A.; Birknes, B.; Martinsen, E.W.; Torsheim, T.; Pallesen, S. Comparing physical exercise in groups to group cognitive behaviour therapy for the treatment of panic disorder in a randomized controlled trial. Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 2013, 41, 408–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sadeghi, K.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Rezaei, M.; Miri, J.; Abdi, A.; Khamoushi, F.; Salehi, M.; Jamshidi, K. A comparative study of the efficacy of cognitive group therapy and aerobic exercise in the treatment of depression among the students. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2016, 8, 54171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, E.B.; Ramsey, L.T.; Brownson, R.C.; Heath, G.W.; Howze, E.H.; Powell, K.E.; Stone, E.J.; Rajab, M.W.; Corso, P. The effectiveness of interventions to increase physical activity: A systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 73–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carron, A.V.; Hausenblas, H.A.; Mack, D. Social influence and exercise: A meta-analysis. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1996, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Jose, C.; Nagpal, T.S.; Coterón, J.; Barakat, R.; Mottola, M.F. The ‘new normal’ includes online prenatal exercise: Exploring pregnant women’s experiences during the pandemic and the role of virtual group fitness on maternal mental health. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feil, K.; Weyland, S.; Fritsch, J.; Wäsche, H.; Jekauc, D. Anticipatory and anticipated emotions in regular and non-regular exercisers—A qualitative study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 929380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Peñacoba, C.; Del Coso, J.; Leyton-Román, M.; Luque-Casado, A.; Gasque, P.; Fernández-Del-Olmo, M.; Amado-Alonso, D. Key factors associated with adherence to physical exercise in patients with chronic diseases and older adults: An umbrella review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rocha, R.; Vieira, F.; Melo, F. Barriers and facilitators of physical activity in pregnancy and postpartum period: A scoping review. Healthcare 2022, 12, 2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broberg, L.; De Wolff, M.G.; Anker, L.; Damm, P.; Tabor, A.; Hegaard, H.K.; Midtgaard, J. Experiences of participation in supervised group exercise among pregnant women with depression or low psychological well-being: A qualitative descriptive study. Midwifery 2020, 85, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, R.; Pelaez, M.; Cordero, Y.; Perales, M.; Lopez, C.; Coteron, J.; Mottola, M.F. Exercise during pregnancy protects against hypertension and macrosomia: Randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 649-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeish, J.; Redshaw, M. Mothers’ accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: A qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participant | Age | Education | Pre-Pregnancy Physical Activity Status | Marital Status | Occupation/Workplace |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | 44 | Vocational secondary | Active | Married | Pharmacy Technician/Pharmacy |

| Participant 2 | 43 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Engineer/Own business |

| Participant 3 | 34 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Clerk/State Water Company |

| Participant 4 | 38 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Sales Specialist/Phone showroom |

| Participant 5 | 40 | Higher | Active | Married | Office Worker/Freight forwarding |

| Participant 6 | 35 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Nutritionist/Private practice |

| Participant 7 | 37 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Massage therapist/Private office |

| Participant 8 | 35 | Secondary | Inactive | Unmarried | Parental leave |

| Participant 9 | 36 | Higher | Inactive | Married | Architect/Online |

| Participant 10 | 35 | Higher | Active | Married | Geodesist geographer/District office |

| Participants | Gestational Week of Last Professional Activity | Sick Leave Status During Pregnancy | Gestational Week Sick Leave Began | Pregnancy Number During Programme Participation | Gestational Week of Programme Enrolment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | 15 | Yes | 15 | 1 | 20 |

| Participant 2 | 38 | No | - | 1 | 6 |

| Participant 3 | 20 | Yes | 20 | 1 | 16 |

| Participant 4 | 9 | Yes | 9 | 1 | 15 |

| Participant 5 | 36 | Yes | 37 | 1 | 14 |

| Participant 6 | 9 | Yes | 9 | 1 | 9 |

| Participant 7 | 20 | Yes | 20 | 1 | 19 |

| Participant 8 | 14 | Yes | 15 | 2 | 20 |

| Participant 9 | 36 | Yes | - | 1 | 13 |

| Participant 10 | 38 | Yes | 24 | 1 | 13 |

| 1. Familiarising yourself with your data | The interview recordings were transcribed verbatim (WG; BM), following which, the authors (BM, WG) read and reread the transcripts to become familiar with the breadth and depth of data discussed and initial ideas were noted. |

| 2. Generating initial codes | The authors (BM, WG) created initial codes systematically, on a line-by-line basis, pertinent to the research question. The codes were then collated across the whole data set. In case of discrepancies, a third co-author was consulted (WF-K). |

| 3. Searching for themes | Codes were collated into potential themes (BM, WG). |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Discussion and generation of themes took place via face-to-face and online meetings with the authors. This helped to ensure that themes were relevant to the related coded abstracts and the entire data set (WG, BM). The analytical strategy was data driven and inductive, with a focus on discussing and identifying the principal themes that repeated throughout transcripts. Themes were revised then validated across the data; quotations were chosen to illustrate identified themes. |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Themes were defined and the overall story of the analysis was drafted (WG, BM, WF-K). |

| 6. Producing the report | The analysis was refined, linking the findings to previous literature and the research question. The broader impact of the findings was considered (BM, WG, WF-K, MP). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makaruk, B.; Grantham, W.; Forczek-Karkosz, W.; Płaszewski, M. “It’s More than Just Exercise”: Psychosocial Experiences of Women in the Conscious 9 Months Specifically Designed Prenatal Exercise Programme—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070727

Makaruk B, Grantham W, Forczek-Karkosz W, Płaszewski M. “It’s More than Just Exercise”: Psychosocial Experiences of Women in the Conscious 9 Months Specifically Designed Prenatal Exercise Programme—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(7):727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070727

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakaruk, Beata, Weronika Grantham, Wanda Forczek-Karkosz, and Maciej Płaszewski. 2025. "“It’s More than Just Exercise”: Psychosocial Experiences of Women in the Conscious 9 Months Specifically Designed Prenatal Exercise Programme—A Qualitative Study" Healthcare 13, no. 7: 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070727

APA StyleMakaruk, B., Grantham, W., Forczek-Karkosz, W., & Płaszewski, M. (2025). “It’s More than Just Exercise”: Psychosocial Experiences of Women in the Conscious 9 Months Specifically Designed Prenatal Exercise Programme—A Qualitative Study. Healthcare, 13(7), 727. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13070727