Self-Study-Based Informed Decision-Making Tool for Empowerment of Treatment Adherence Among Chronic Heart Failure Patients—A Pilot Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Outcome Measure

2.4. Recruitment Site

2.5. Study Population

2.6. Inclusion Criteria

2.7. Exclusion Criteria

2.8. Tool

2.9. Study Execution

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Störk, S.; Handrock, R.; Jacob, J.; Walker, J.; Calado, F.; Lahoz, R.; Hupfer, S.; Klebs, S. Epidemiology of heart failure in Germany: A retrospective database study. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2017, 106, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donzé, J.; Lipsitz, S.; Bates, D.W.; Schnipper, J.L. Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2013, 347, f7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumholz, H.M.; Lin, Z.; Keenan, P.S.; Chen, J.; Ross, J.S.; Drye, E.E.; Bernheim, S.M.; Wang, Y.; Bradley, E.H.; Han, L.F.; et al. Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013, 309, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.Y.; O’riordan, D.L.; Marks, A.K.; Bischoff, K.E.; Pantilat, S.Z. A Comparison of Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure and Cancer Referred to Palliative Care. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e200020. [Google Scholar]

- Selman, L.; Beynon, T.; Higginson, I.J.; Harding, R. Psychological, social and spiritual distress at the end of life in heart failure patients. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2007, 1, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.K.; Dennison-Himmelfarb, C.R.; Szanton, S.L.; Bone, L.; Hill, M.N.; Levine, D.M.; West, M.; Barlow, A.; Lewis-Boyer, L.; Donnelly-Strozzo, M.; et al. Community Outreach and Cardiovascular Health (COACH) Trial: A randomized, controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2011, 4, 595–602. [Google Scholar]

- Gislason, G.H.; Rasmussen, J.N.; Abildstrom, S.Z.; Schramm, T.K.; Hansen, M.L.; Buch, P.; Sørensen, R.; Folke, F.; Gadsbøll, N.; Rasmussen, S.; et al. Persistent use of evidence-based pharmacotherapy in heart failure is associated with improved outcomes. Circulation 2007, 116, 737–744. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, I.; Wolf, A.; Olsson, L.-E.; Taft, C.; Dudas, K.; Schaufelberger, M.; Swedberg, K. Effects of person-centered care in patients with chronic heart failure: The PCC-HF study. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, V.V.; Riegel, B. Are we teaching what patients need to know? Building skills in heart failure self-care. Heart Lung 2009, 38, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Légaré, F.; Witteman, H.O. Shared decision-making examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 276–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ruppar, T.M.; Cooper, P.S.; Mehr, D.R.; Delgado, J.M.; Dunbar-Jacob, J.M. Medication Adherence Interventions Improve Heart Failure Mortality and Readmission Rates: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Controlled Trials. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e002606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krah, N.S.; Zietzsch, P.; Salrach, C.; Toro, C.A.; Ballester, M.; Orrego, C.; Groene, O. Identifying Factors to Facilitate the Implementation of Decision-Making Tools to Promote Self-Management of Chronic Diseases into Routine Healthcare Practice: A Qualitative Study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kallio, H.; Pietilä, A.; Johnson, M.; Kangasniemi, M. Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 2954–2965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seferović, P.M.; Piepoli, M.F.; Lopatin, Y.; Jankowska, E.; Polovina, M.; Anguita-Sanchez, M.; Störk, S.; Lainščak, M.; Miličić, D.; Milinković, I.; et al. Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology Quality of Care Centers Program: Design and accreditation document. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 763–774. [Google Scholar]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar]

- Jonkman, N.H.; Westland, H.; Groenwold, R.H.; Ågren, S.; Anguita, M.; Blue, L.; de la Porte, P.W.B.-A.; DeWalt, D.A.; Hebert, P.L.; Heisler, M.; et al. What Are Effective Program Characteristics of Self-Management Interventions in Patients With Heart Failure? An Individual Patient Data Meta-analysis. J. Card. Fail. 2016, 22, 861–871. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B.; Bennett, J.A.; Davis, A.; Carlson, B.; Montague, J.; Robin, H.; Glaser, D. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: Issues of measurement and etiology. Am. J. Crit. Care 2002, 11, 520–528. [Google Scholar]

- Van Spall, H.G.; Rahman, T.; Mytton, O.; Ramasundarahettige, C.; Ibrahim, Q.; Kabali, C.; Coppens, M.; Haynes, R.B.; Connolly, S. Comparative effectiveness of transitional care services in patients discharged from the hospital with heart failure: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 19, 1427–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Lainscak, M.; Blue, L.; Clark, A.L.; Dahlström, U.; Dickstein, K.; Ekman, I.; McDonagh, T.; McMurray, J.J.; Ryder, M.; Stewart, S.; et al. Self-care management of heart failure: Practical recommendations from the Patient Care Committee of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Davidson, K.W.; Mangione, C.M.; Barry, M.J.; Nicholson, W.K.; Cabana, M.D.; Caughey, A.B.; Davis, E.M.; Donahue, K.E.; Doubeni, C.A.; et al. Collaboration and Shared Decision-Making Between Patients and Clinicians in Preventive Health Care Decisions and US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations. JAMA 2022, 327, 1171–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D.; Légaré, F.; Lewis, K.; Barry, M.J.; Bennett, C.L.; Eden, K.B.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Llewellyn-Thomas, H.; Lyddiatt, A.; Thomson, R.; et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 4, CD001431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballester, M.; Orrego, C.; Heijmans, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Versteegh, M.M.; Mavridis, D.; Groene, O.; Immonen, K.; Wagner, C.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; et al. Comparing the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-management interventions in four high-priority chronic conditions in Europe (COMPAR-EU): A research protocol. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034680. [Google Scholar]

- Liedholm, H.; Linné, A.B.; Agélii, L. The development of an interactive education program for heart failure patients: The Kodak Photo CD Portfolio concept. Patient Educ. Couns. 1996, 29, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Strömberg, A.; Ahlén, H.; Fridlund, B.; Dahlström, U. Interactive education on CD-ROM—A new tool in the education of heart failure patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 46, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amaritakomol, A.; Kanjanavanit, R.; Suwankruhasn, N.; Topaiboon, P.; Leemasawat, K.; Chanchai, R.; Jourdain, P.; Phrommintikul, A. Enhancing Knowledge and Self-Care Behavior of Heart Failure Patients by Interactive Educational Board Game. Games Health J. 2019, 8, 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.S.; Li, P.W.; Li, S.X.; Smith, R.D.; Yue, S.C.; Yan, B.P.Y. Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of an Empowerment-Based Self-care Education Program on Health Outcomes Among Patients With Heart Failure: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e225982. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B.; Dickson, V.V.; Faulkner, K.M. The Situation-Specific Theory of Heart Failure Self-Care: Revised and Updated. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2016, 31, 226–235. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, G.C.; Liljeroos, M.; Dwyer, A.A.; Jaques, C.; Girard, J.; Strömberg, A.; Hullin, R.; Schäfer-Keller, P. Symptom perception in heart failure—Interventions and outcomes: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 116, 103524. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, G.C.; Liljeroos, M.; Hullin, R.; Denhaerynck, K.; Wicht, J.; Jurgens, C.Y.; Schäfer-Keller, P. SYMPERHEART: An intervention to support symptom perception in persons with heart failure and their informal caregiver: A feasibility quasi-experimental study protocol. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e052208. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.-Y.; Han, H.-R.; Jeong, S.; Kim, K.B.; Park, H.; Kang, E.; Shin, H.S.; Kim, M.T. Does knowledge matter?: Intentional medication non-adherence among middle-aged Korean Americans with high blood pressure. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2007, 22, 397–404. [Google Scholar]

| Control Group (n = 40) | Test Group (n = 40) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 32 (80) | 30 (75) | 0.79 |

| Age, y | 56 (47–62) | 61 (53–68) | 0.04 |

| Natives French study participants (n; %) | 28 (70) | 31 (78) | 0.61 |

| ETIOLOGY | |||

| Ischemic only (n; %) | 13 (32) | 10(25) | 0.62 |

| Mixed origin (n; %) | 9 (22) | 8 (20) | 1.00 |

| Non-ischemic (n; %) | 18 (45) | 22 (55) | 0.50 |

| Heart failure subgroup | |||

| <40% (n; %) | 30 (75) | 33 (83) | 0.59 |

| 41–49% (n; %) | 6 (15) | 5 (13) | 1.00 |

| >50% (n; %) | 4 (10) | 2 (5) | 0.68 |

| Clinical severity | |||

| NYHA I (n; %) | 16 (40) | 17 (43) | 1 |

| NYHA II (n; %) | 13 (33) | 17 (43) | 0.49 |

| NYHA III (n; %) | 9 (23) | 6 (15) | 0.57 |

| NYHA IV (n; %) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 |

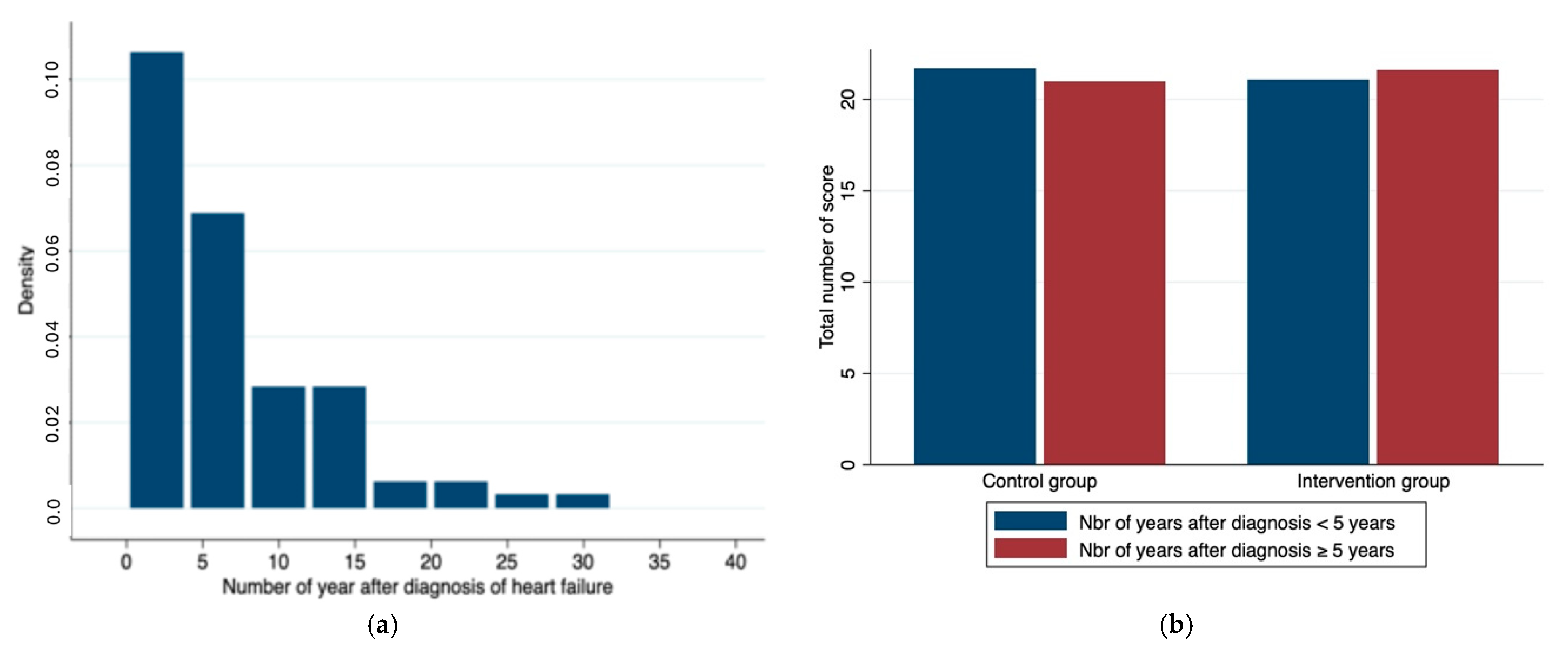

| Number of years after diagnosis (y) | 4 (2.5–9.5) | 5.5 (2–8.5) | 0.61 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Smoking (n; %) | 7 (18) | 10 (25) | 0.59 |

| Arterial hypertension (n; %) | 32 (80) | 27 (68) | 0.31 |

| Dyslipidemia (n; %) | 31(78) | 26 (65) | 0.32 |

| Positive family history (n; %) | 0 (0) | 2 (8) | 0.24 |

| Number of Cardiovascular RF (n) | 2 (1–3) | 2 (1–3) | 0.77 |

| Others | |||

| CABG (n; %) | 4 (10) | 7 (18) | 0.52 |

| Valvopathy (n; %) | 31 (76) | 23 (58) | 0.09 |

| Defibrillator (n; %) | 19 (48) | 28 (45) | 1 |

| Resynchronization therapy (n; %) | 13 (33) | 8 (20) | 0.31 |

| Previous cardiorespiratory arrest (n; %) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | 0.24 |

| Control Group (n = 40) | Test Group (n = 40) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition | 9 (22) | 12 (30) | 0.61 |

| TD <25% (n; %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| TD 25–49% (n; %) | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 1 |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 3 (8) | 4 (10) | 1 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 4 (10) | 6 (15) | 0.74 |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockade | 12 (30) | 6 (15) | 0.18 |

| TD <25% (n; %) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 1 |

| TD 25–49% (n; %) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 5 (13) | 1 (3) | 0.20 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 3 (8) | 1 (3) | 0.62 |

| Angiotensin receptor Neprilysin inhibition | 17 (43) | 18 (45) | 1 |

| TD <25% (n; %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

| TD 25–49% (n; %) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | 1 |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 8 (20) | 9 (23) | 1 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 8 (20) | 7 (16) | 1 |

| ß-blocker treatment | 32 (80) | 32 (80) | 1 |

| TD <25% (n; %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| TD 25–49% (n; %) | 12 (30) | 17 (43) | 0.35 |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 7 (18) | 7 (18) | 1 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 13 (33) | 7 (18) | 0.19 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 25 (63) | 28 (70) | 0.6 |

| TD <25% (n; %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| TD 25–49% (n; %) | 6 (15) | 9 (23) | 0.57 |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 9 (23) | 14 (35) | 0.32 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 10 (25) | 5 (13) | 0.25 |

| SGLT2 inhibition | 24 (60) | 20 (50) | 0.5 |

| TD <50% (n; %) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| TD 50–74% (n; %) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 |

| TD 75–100% (n; %) | 23 (58) | 19 (48) | 0.50 |

| Loop diuretic treatment (n; %) | 13 (33) | 17 (43) | 0.49 |

| Pharmacological classes per patient (n; %) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.81 |

| Control Group (n = 40) | Test Group (n = 40) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median sum of the points | 22 (19–24) | 22 (19–24) | 0.65 |

| Statement 1: HF is a chronic life-long disease | 3.5 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.19 |

| Statement 2: Foundational drug treatment of HF disease intends patient’s well-being | 4 (3–4) | 4 (4–4) | 0.22 |

| Statement 3: The combination of HF drugs delays progression of HF disease | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.009 |

| Statement 4: Daily intake of HF drugs is consistent with the vision of HF | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 0.004 |

| Statement 5: Controls: understanding of different aspects of my heart disease; test group: all questions are answered * | 3 (2.5–4) | 1 (0–1.5) | <0.001 |

| Statement 6: Improved understanding the different aspects of disease | 2 (1–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.03 |

| Statement 7: Empowerment to take an informed decision for adherence self-management | 3.5 (3–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.28 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iten, L.; Selby, K.; Glauser, C.; Schukraft, S.; Hullin, R. Self-Study-Based Informed Decision-Making Tool for Empowerment of Treatment Adherence Among Chronic Heart Failure Patients—A Pilot Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060685

Iten L, Selby K, Glauser C, Schukraft S, Hullin R. Self-Study-Based Informed Decision-Making Tool for Empowerment of Treatment Adherence Among Chronic Heart Failure Patients—A Pilot Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(6):685. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060685

Chicago/Turabian StyleIten, Lea, Kevin Selby, Celine Glauser, Sara Schukraft, and Roger Hullin. 2025. "Self-Study-Based Informed Decision-Making Tool for Empowerment of Treatment Adherence Among Chronic Heart Failure Patients—A Pilot Study" Healthcare 13, no. 6: 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060685

APA StyleIten, L., Selby, K., Glauser, C., Schukraft, S., & Hullin, R. (2025). Self-Study-Based Informed Decision-Making Tool for Empowerment of Treatment Adherence Among Chronic Heart Failure Patients—A Pilot Study. Healthcare, 13(6), 685. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13060685